The Relative Decline Of Malay Shipping In The Malay Peninsula During The 19th Century

By Scot Abel

Introduction

For untold centuries, the perahu (sailing vessels) of the Malay people plied the waters of the Indonesian archipelago for the purposes of trade, warfare and fishing. Yet, once the legendary Malay shippers who spread Bahasa Melayu (the Malay language) throughout the archipelago eventually faded from the scene, the ubiquitous perahu similarly disappeared from the crowded waterways of the Straits of Malacca and beyond. This transformation resulted largely from the policies of peninsular Malay states that limited Malay shipping in the carrying trade or intraregional shipping to the elites and those deemed non-threatening, thereby sending trade into a relative decline during the 19th century.

Malays considered maritime trading in the early 19th century a highly respectable and honorable profession. The second Resident of Singapore John Crawfurd had recounted, “To engage in commerce is reckoned no dishonour to anyone, but the contrary, and it is, indeed, among the maritime tribes especially, one of the most dignified occupations even of the sovereign himself, and of his principal officers…”1 thereby acknowledging shipping as a desirable profession for many in the archipelago. For coastal communities, engaging in commerce offered opportunities for wealth and respectability within society. Partaking in maritime trade, in particular, was deemed so honourable for Malays that even sultans had trading interests.

Malay Maritime Trading and Political Power

Malay states during the early 19th century maintained a political system dependent on the prestige of rulers, which enabled them to attract and support followers who were necessary in order to have political power. The peninsular Malay kingdoms came under pressure from small polities that wished to increase their power and perhaps even become kingdoms themselves. The mobility of other rajas (elites) enabled them to establish or conquer new seats of power for themselves.2 Culturally, the rajas maintained their prestige and power through the splendour of their palaces, clothing worthy of their ranks and appropriate speech that reinforced their authority.3 The maintenance of political power in Malay states required rulers to act appropriately to ensure sufficient political support, while failure to secure such support possibly meant the fracturing of the state.

At the end of the 18th century, Malay shippers dominated the carrying trade in the Straits of Malacca and adjacent waters. By 1785, Malacca had recovered its role as the leading port in the Straits of Malacca in terms of long-distance shipping after Dutch East India Company forces crushed the Bugis of Riau.4 Between 1770 and 1785, Malay nakhoda, or vessel masters, made up the largest nationality that commanded vessels entering Malacca. In 1785, nakhoda identifying as Malay outnumbered all other ethnic groups combined as commanders of vessels entering that port.5 Between May 1862 and April 1863, the most common “native craft” entering Malacca from other harbours on the Malay peninsula were Malay state-flagged vessels.6 Malacca remained a bastion for Malay shipping, though its trade routes likely changed over the decades.

With Malacca’s decreasing relevance as a trade port, its Malay shippers, too, became less relevant over the years. Over time, sediment from erosion silted up Malacca’s harbour, making arrivals by deep-draft Western squarerig vessels more difficult. The town’s merchants petitioned the Straits Settlements government in 1826 concerning this but to no avail.7 The harbour retained its status long into the 19th century as a destination of tin from the Malay states of Selangor and Perak, which arrived in small perahu.8 Without a deep-water harbour for much of the 19th century, Malacca stood no chance against other regional ports, such as Singapore, that facilitated international trade more efficiently.

On the trading rivalry between Penang and Singapore, Robert Fullerton’s statement of 26 July 1825 noted, “the Government [will have] nothing to do with the mercantile jealousy of either and must look to the general interests of all, and because I think both are eminently useful…”.9 Fullerton argued that Singapore and Penang would each draw trade from the surrounding region mainly at the expense of foreign ports nearby rather than each other, with Malacca likely attracting trade from ports located immediately within the Straits of Malacca such as Siak. From the Straits Settlements, goods usually went on to distant major markets.10 The Indian and Straits Settlements governments’ policies of focusing on Singapore and Penang relegated Malacca to a small harbour receiving goods from only its nearby neighbours. Even though these policies disproportionately affected Malay shippers, the Straits government sought to avoid preferential treatment for them or create laws to mitigate their effects to legitimise their rule. The Straits Settlements sought to attract shipping from other lands more so than developing a local merchant fleet to engage in trade throughout the Indian archipelago.

While the Straits Settlements were functionally indifferent to the plight of the Malay shipper, Malay states were usually hostile toward independent Malay shippers due to fears of concentrated wealth challenging their power. Malay rulers employed their wealth as a means to attract Malay subjects who possessed a great deal of mobility and reserved the right to move elsewhere. This system, known as* kerajaan* economics, enabled Malay rulers to use wealth to attract followers and seize the wealth of potential rivals whose properties enabled them to challenge established authorities by attracting followers of their own or incorporating them into their state.11 Given the importance of the shipping industry to the Malay peninsula and the wealth it generated, an independent Malay merchant class potentially threatened the power of the Malay ruling elite.

Malay States and Monopolies

The shipping industry in the Malay states during the 19th century operated largely via royal monopolies. In his 1820 work on the Indian Archipelago, John Crawfurd noted the rarity of regular duties implemented by Malay governments that instead used commercial monopolies, observing that “[a] Malay prince is … in general the first and often the only merchant in his country”.12 Foreigners obtained trading rights by gaining permission to do so from the local ruler in exchange for gifts. During this time, certain ports retained fairly open trading policies, which Crawfurd ascribed especially to states where “Arabs and their descendants [had] obtained sovereignty,” along with places where an effective shahbandar (an official specialising in mercantile and foreign affairs) managed the harbour, such as in Malacca, Palembang and Aceh.13 In the first two decades of the 19th century, there remained successful Malay ports, while the archipelago also had systems based on royal monopolies and trading privileges.

While sailing along the east coast of Malaya during the early 1830s, George Windsor Earl, a British adventurer, noted the existence of commercial monopolies that were held by the governments there. During his stay in Terengganu in 1833, Earl described the government as an aristocracy with the sultan as the nominal authority elected by the pangerans, or noble lords.

They surrounded themselves with dependents who shunned “honest” work. “The Sultan and the pangerans form a sort of commercial company, and monopolize [sic] the whole of foreign trade,” described Earl who also noted they required locals to buy solely from them.14 Earl, in contrast to Crawfurd, depicted Arabs and their laws as a negative influence on Malay society.15 The monopolistic system controlled by Malay elites ensured that no potential political challenger arose from the masses and that the state’s wealth was kept for themselves and their supporters. The monopolisation of foreign shipping rights by the elite inhibited the rise of independent merchants.

Singapore’s Trade with the East Coast of Malaya

Given the maritime trading needs of the inhabitants of the Malay Peninsula, along with the nature of Malay politics, shipping played an important role in the economies of the east coast of Malaya. Seafarers plied these waters with vessels known as sampan-pukats, loading cargo from the states of Pahang, Terengganu and Kelantan to Singapore for distribution elsewhere.16 Earl described one such vessel as “a long open boat” capable of fending off pirate attacks, which, in his experience, had a crew of around 35.17 These vessels formed an integral part of the trade that enabled goods from the east coast of Malaya to be transported elsewhere for consumption, and eventually dominated the carrying trade.

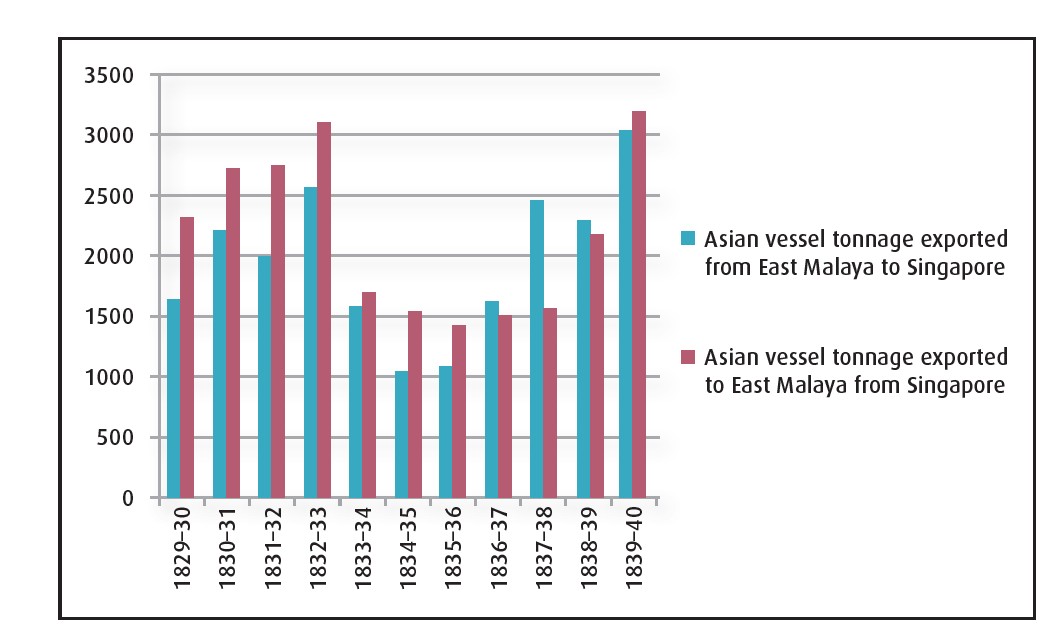

Trade between Singapore and the Malayan east coast slumped during the mid-1830s but managed to recover by the end of the decade. From around 1834 to 1837, commerce between the east coast of Malaya and Singapore experienced a trading slump (see Figure 1) that forced the industry to undertake reforms. Pirate attacks, misconduct of officers and excessive supply all contributed to the decline in trade. During the early 1830s, there were 14 or 15 sampan-pukat that sailed between Singapore and East Malaya. This dropped to four for most of 1836. By the start of 1837, that number had rebounded to eight vessels and looked set for further growth.18 Such volatility required adequate organisation and support to fend off pirates and rebuild after potentially devastating losses from their attacks.19

The organisational restructuring of the trade culminated with Chinese merchants dominating the export trade of the Malayan east coast. “The few Chinese merchants”… who … “exclusively managed” the Singapore- Malayan east coast trade became more cautious, selecting nakhoda they trusted because of their “character and experience,” and who possessed some capital.20 Singapore’s merchant community reformed ensuring those engaged in the trade were responsible for losses rather than external creditors, thereby forcing greater caution onto the shipping industry. With piracy in sharp decline after 1836, the trade of gold dust, tin and pepper from East Malaya to Singapore recovered.21 The trading reforms hardened the resolve of merchants and seafarers to ensure the success of trading missions. With each nakhoda personally vested in the voyage, the odds of success increased as surrendering cargo to either pirates or other causes became less desirable. Seafarers became less likely to give up when their livelihoods were at stake. With creditors no longer footing the losses of Singapore merchant traders, the latter became more careful with whom they selected to safeguard their investments. Chinese merchants in Singapore possibly preferred nakhoda of their own ethnicity or dialect rather than Malays or other groups, thereby weakening them.

Straits Chinese Merchants

For the Straits Chinese, working with people they trusted, such as family and those of a similar ethnic background, meant smoother business transactions. European newcomers moving to Penang would hire Chinese contractors to construct their homes for them. These contractors in turn offered referrals to their relatives who could provide furniture, clothing and servants, or services such as regularly purchasing food for the household in exchange for a monthly payment.22 Though such methods increased efficiency and united families economically, they also kept non-relatives and other ethnic groups out of particular sectors of the Malayan economy and exacerbated wealth gaps.

By 1837, the trade between the Malayan east coast and Singapore, then dominated by Chinese, had only a few Malay shippers. The east coast’s exports to Singapore were “…almost entirely imported by Chinese pukats – a comparatively small portion of the trade being in the hands of the Malays themselves”.23 The writer explains that this resulted from “… the wretched policy which prevails in all these petty native states, where the Rajah himself is generally the principal trader, and almost always a monopolist. Each of these pukats generally carries twenty-nine men, all Chinese, who compose a partnership among themselves, every individual on board being interested, some more, some less, in the general result of the whole adventure, and no one among them being paid anything under the name of wages”.24 The crew usually comprised 26 common seafarers and three officers, who consisted of the nakhoda, clerk and business agent or sometimes just the nakhoda himself. However, the Chinese merchants in port “almost always” owned the vessels, rather than the crew, and managed them from Singapore, while significant creditors of the vessel often owned a stake in the cargo.25 The Chinese, based in Singapore, effectively controlled shipping to the east coast of Malaya from the sampan-pukat owners down to the regular seafarers who manned the vessels and owned cargo. Chinese shippers surpassed their Malay counterparts in trade mainly because policies of Malay states favoured them.

Why did Malay rulers permit Chinese merchants to engage in commerce when they excluded others from doing so? As Crawfurd explained concerning the carrying trade of the Indian Archipelago: “The peaceable, unambitious, and supple character of the Chinese, and the conviction on the part of the native governments, of their exclusive devotion to commercial pursuits, disarm all jealousy, and make them welcome guests everywhere. This very naturally and very justly gives them an equitable monopoly of the carrying trade…”.26 Granting trading monopolies to Chinese merchant syndicates appeared to Malay rulers as the politically safest option because of their apparent lack of political ambition. Even if a Chinese leader sought political power, the leader would almost certainly have had difficulty gaining the loyalty of Malay subjects, especially if he did not adopt Malay customs and Islam.

The leadership of these Malayan-Chinese communities were also officials who governed affairs within the Malay states. The formal leader of the Chinese community in Malay state systems became known as the “kapitan China,” evolving from the Malacca Sultanate position of shahbandar. After the Portuguese conquered Malacca in 1511, they adapted the position to a more militaristic role by mobilising and leading troops from a particular community. The Dutch and Malay states borrowed the title of “kapitan” and offered it to Chinese community leaders for their respective governments.27 The kapitan China and his followers supported the Malay ruling elite, while Chinese merchants received either commercial monopolies or favourable trading terms. The relationship between the Chinese merchant community and Malay rulers functioned by splitting wealth and power between themselves. Though this relationship proved untenable at times and in certain places, it persisted long enough to undercut the market share growth of Malay shippers that was critical during a long growth period.

Power, Politics and Malay Merchants

The Malay political leadership saw Malay merchants as potential threats to their power, which made them prefer non-Malays as state-sanctioned merchants. Despite their fame throughout the archipelago and beyond, Malay maritime traders in peninsular Malay states lacked the same status for much of the 19th century. Prior to the late 18th century, the Malay Peninsula had fewer prominent Malay traders in comparison with other ethnic groups, because Malay merchants operated from other ports in Southeast Asia instead. The peninsular Malay states likely preferred non- Malay merchants to conduct trade.28

Malay rajas so feared wealthy Malays, especially traders, that they developed policies to prevent their rise because of the way in which wealthy Malays obtained power.29 Frank Swettenham, a British official, frequently witnessed the loss of property by seizure during the 19th century in Malaya, which he partially accounted for the socio-economic problems there.30 Aside from a lack of security from theft, Malay commoners lost their wealth to the kerajaan system, which prevented the rise of political opponents. The Malay states permitted Chinese communities to accumulate wealth through their own legal system because they were perceived as outsiders. Engaging in commerce meant working for the ruler or having status within the political hierarchy.31 Wealthy Malay traders stood to face political problems if they wanted to live on the Malay Peninsula because of the political barriers erected by the Malay states.

Arab merchants often worked within Malay political structures and perceptions to secure a place within the shipping industry of Malaya. Arab shipping merchants often received special privileges from Malay rajas, making Arab merchants less vulnerable to their whims than Malays. While at Pahang, Munshi Abdullah noted that the Arabs there were all merchants who lived near Kampong China and were revered by Malays as rajas and were treated as such having come from the Holy Land.32 Aside from developing relationships with the Malay states, Arab merchants such as Syed Massim bin Salleh Al Jeoffrie settled in Singapore while owning large sailing vessels and steamers to conduct trade in the archipelago.33 Straits Arab traders had advantages over their Malay counterparts because of their more favourable relationships with Malay rulers. These relationships allowed them to develop their own shipping networks and prosper, which in turn enabled them to acquire more sophisticated shipping technology as the century progressed and permitted them to remain competitive in the shipping industry.

The Rise of Free Trade

Singapore adopted free trade policies that empowered regional merchants, who in turn became more resilient to the demands of Malay rajas. Sir Stamford Raffles ordered Singapore’s first resident, William Farquhar, not to impose tariffs on Singapore’s commerce when they established a factory there in 1819. Traders flocked to Singapore, drawn by the promises of no tariffs and low port fees. The Malay rajas in Singapore demanded gifts from the nakhoda but by April 1820, with Raffles’ reforms, the nakhoda had won the right not to offer gifts to them.34 This remained a thorny issue in 1821 when Sultan Husain ordered a junk master from Amoy, China to be placed in the stocks for failing to provide him with a gift, though the junk master was freed by Resident Farquhar shortly after.35 Governor Robert Fullerton pushed the Straits Settlements even further toward free trade by eliminating fees for perahu and junks visiting Penang in December 1826.36 The new free trade policies enabled foreign merchants to resist more effectively the demands of government officials. Foreign merchants, especially those from China, sailing the trading routes from the Straits Settlements to the Malay states, became increasingly assertive in their relationship with governments.

Mercantile shipping became a powerful force within the Straits Settlements that promoted and used liberal policies to its advantage. Malay shippers from throughout the archipelago sailed to Singapore to trade. According to Governor Blundell of the Straits Settlements in 1856, Malay shippers particularly enjoyed the policies of free trade, not so much because of the monetary benefits, but rather for the lack of government interference. The corruption of customs houses throughout the archipelago, practised by local rulers and Europeans alike, so frustrated Malay shippers that Singapore’s less corrupt system attracted them, because they knew they did not need to pay a customs house.37 Within Singapore itself, however, Malay shippers owned just three schooners totaling 149 tonnes out of Singapore’s registry of 29,573 tonnes of Western square-rig shipping – less than one percent of the total tonnage at one point during the mid-1850s.38 Though Singapore became a popular destination for shipping throughout the archipelago, few Malays registered any Western-style vessels there. Without acquiring these vessels, keeping up with long-term shipping trends became increasingly difficult.

In the face of a trading environment determined by Britain’s economic liberalism, some Malay states outside the peninsula were more adept at protecting their shipping industries from foreign firms than their peninsular compatriots. Sumatran Malay states, such as Kampar and Siak, prospered from trade with Singapore by sending convoys of 12 to 20 perahu, each with a crew numbering between 20 and 30, as part of the Malay-Arab elite’s commercial enterprises. Malays held the Kampar-Singapore route with nakhoda renting vessels from the ruling elite at a tonnage rate of $30 for a 20-tonne perahu in Kampar. After selling goods in Singapore, they purchased cargo and returned home.39 Malay nakhoda and crews all owned a portion of the cargo and had no substantive Chinese competition in the 1830s because of the latter’s absence in Kampar.40 In the early 20th century, the royals from Pulau Penyengat purchased a steamship to ferry goods from the Riau Archipelago to Singapore.41 Malays outside the Malay Peninsula shipped goods to Singapore even into the 20th century despite, or perhaps because of, the liberal shipping policies enacted by the Straits Settlements.

Winds of Change

Siam’s littoral political economy was remarkably similar to the peninsular Malay states. Like the Malay states, much of Siam’s economy consisted of monopolies owned by Siamese lords, or senabodi. When King Mongkut of Siam decided on substantive economic reforms, he received the support of the Bunnag family, merchants who were of Iranian decent and were the wealthiest and most powerful trading family in the kingdom. One family member, Chuang Bunnag, disliked the old system because taxes oppressed the poor and limited the goods available for export. Chuang Bunnag sought British support to remove the entrenched power structures through the Bowring Treaty (signed in 1855 between Great Britain and Siam to facilitate greater trade among other issues).42 The Siamese had a system akin to the Malay kerajaan economics structure and used British influence to undermine the previous system. Unlike the Malay rajas, Siam transformed its economy without sacrificing its sovereignty but at the cost of its previous economic and political policies.

Maritime development exemplified the increasing sophistication of the central state and the power of the king. Siam removed its previous economic restrictions and reformed the kingdom, allowing for economic expansion, which enabled the government to expand its naval power. King Mongkut’s reign saw the first steam vessels used by a Siamese government. The new steam vessels increased the prestige of the monarchy, while proving useful for naval patrols and various government functions. Additionally, the Siamese government constructed new sailing vessels as part of its building programme during the 1850s. Eventually, both government- and civilianowned steam vessels became more common in Siamese waters, with even Chinese merchants there acquiring steam vessels.43 The acquisition of steam vessels and the development of Siam’s shipping industry during the second half of the 19th century required a degree of political centralisation and economic reform.

The peninsular Malay states faced similar trade headwinds with the rise of free trade and more powerful merchants independent of state control. Under the monopolistic system, Malay rulers employed their authority and monopolies to acquire goods from their people at below market-value rates and then sold the goods to foreign merchants. For instance, the temenggong in Singapore purchased agar-agar, a type of seaweed, as per tradition at $6 for 12 pikuls, even though its market prices ranged from $30 to $40.44 The Malay elites then sold the goods they received at much higher prices. A monopoly on foreign trade resulted in higher prices than if foreigners bought the goods directly from producers. The Straits Settlements’ free trade system undermined such monopolies because foreign merchants became less willing to accept higher prices. This in turn eroded kerajaan revenues and contributed to political instability in Malaya because the rulers lacked funds to support their political bases.45 By 1837, the sultan of Kelantan had adopted “a more liberal system of trade” than other rulers in Malaya, attracting more merchants to his harbour by avoiding a monopolistic trade system.46 Malay states came under new economic pressures with kerajaan economics becoming less feasible in the face of free trade.

The peninsular Malay rulers came under heavy pressure to reform their revenue systems and move away from the monopolistic aspects of kerajaan economics by foreign merchants but such a transition caused great challenges. The bendahara (chief minister) of Pahang attempted to keep a foreign trade monopoly by compelling the sampan-pukat shippers to trade only with him. The domestic industry suffered as Chinese gold and tin miners went on strike and later fled rather than accept the raja’s conditions. Eventually, the bendahara moved from a monopoly-based system to one reliant more on heavy customs duties.47 Kelantan experienced dissent from Chinese miners during this period, though their motivations were murky. Chinese miners had killed the temenggong of Kelantan at Pulai, Kelatan, supposedly at the instigation of another Malay chief. However, the temenggong’s son avenged his father’s death by slaughtering the Chinese miners there.48 Though the miners’ motives for resorting to violence remains unclear, the incident suggested that liberalising commerce exacerbated the inter-factional violence within the Malay states. The economic changes of the 19th century shook the foundations of the kerajaan economics system found in the Malay Peninsula, particularly as foreigners gained more power within Malay states and used kerajaan economics to their advantage.

In contrast, Siam was able to take better advantage of the situation brought on by liberalisation, perhaps because of its closer cooperation with locally based mercantile elites, whereas peninsular Malay states lacked sufficient strength and internal cooperation and cohesiveness to adapt. Shipping merchants once deemed non-threatening became too powerful to control by either the Straits Settlements or Malay states resulting in Malay shipping losing its former market share. Despite the significance of the industry, few, if any, regional governments seemed interested in protecting Malay shippers. The competition became too fierce for Malays shippers, save a few elites, to participate in the steam shipping industry by the close of the century. The Siamese centralised their political power and adapted new maritime technologies more successfully than their peninsular Malay counterparts who took considerably less action in developing their maritime capacity along Western lines.

Despite overwhelming odds and a challenging political environment, Hajjah Fatimah binte Sulaiman, a peninsular Malay shipping merchant, emerged during the 19th century and set up a successful shipping firm. Fatimah was from a prominent family in Malacca. Her first marriage failed and she moved to Singapore to start afresh.49 Fatimah employed her connections with the rajas of the peninsular Malay states in her trading and married a Bugis prince from Gowa and bore a child named Raja Siti. With Fatimah’s abilities and political connections, she developed a trading fleet of numerous perahu and other vessels that sailed the waters of Malaya and the archipelago.50 Her daughter subsequently married the son of an Arab merchant in Singapore, who eventually took over her business. The business survived two robberies and a fire, after which the family built a mosque on Beach Road in Singapore where they held feasts for Muslims of all backgrounds twice a year.51 Fatimah, though independent of Malay rulers, likely obtained success through her relationships with them and having royal support from her husband’s family. Perhaps Malay rajas had dismissed her as a threat because of her gender, but, in any case, she managed a shipping firm that eventually assimilated into the cosmopolitan Islam of Singapore, where non-Malay Muslims, including the overseas Arab community into which her daughter married, thrived.

Munshi Abdullah described the policies of Malay rulers in a manner that fit the framework of kerajaan economics well. After witnessing the destitution of Pahang during his voyage in 1838, he considered the reasons for such poverty and determined that the “oppression and cruelty of the rajas” caused such hardship that people gave up trying to obtain wealth because the rajas seized anything of value.52 He made similar assertions about the corruption of Malay rule concerning Terengganu. For commoners, staying poor became a survival strategy because if a man obtained anything, the raja would usually demand a gift or loan. If anyone resisted, the raja would likely kill the resistors and their families.53 In Kelantan, a man reported a situation where rajas had seized homes and slaughtered those who disobeyed them.54 Munshi Abdullah determined that the causes of poverty in Malay states came down to a lack of peace and security for subjects and their properties, where the elites perpetually mistreated their people by seizing their properties and killing them. As a result, the Malays lacked any incentive to develop the land and stayed idle.55 Such analysis by Munshi Abdullah and others reflect the concept of kerajaan economics. Malay elites monopolised the economic capacity of a state out of fear that a leader might become strong enough to challenge them and destroy the elite’s hold on power.

The peninsular Malay states sent the Malay carrying trade into a relative decline through policies that favoured the Malay ruling elites and their political allies who they had deemed as less threatening during the 19th century. We can still see visual evidence of this in 21st century Singapore through the two old Malay quarters of Kampong Gelam and Telok Blangah, each of which possessed its own Malay ruler separated by the formerly bustling Singapore River. The Istana Kampong Gelam once housed the royal family that ruled from Singapore. Its neighbourhood remains a testament to the Islamic cosmopolitanism of Singapore with streets names that echo the distant cities of Baghdad, Kandahar and Muscat. Though the neighbourhood has changed much since the 19th century, it still hosts shops akin to those in the past. Hardly any evidence of the once thriving Malay village at Telok Blangah remains, save for Masjid Temenggong Daeng Ibrahim and its adjacent cemetery, where the ancestors and relatives of the current Sultan of Johor lie. Despite the rajas of Telok Blangah ultimately attaining greater wealth than the royal family at Kampong Gelam, the former Malay village has lost nearly any semblance of its former life. Kerajaan economics prevented ordinary Malays from obtaining great wealth in Telok Blangah. The residents of Kampong Gelam, however, had more economic opportunities largely because of the different policies enacted by authorities there. This contrast is just one example of the enduring legacy of kerajaan economics, when rulers stifled Malay enterprise.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the National Library Board of Singapore for giving me this opportunity to conduct research. I would like to credit The British Library, The National Archives (United Kingdom), and the National Archives of India for granting me access to their material. I would also like to thank Gracie Lee, Gladys Low, Joanna Tan, Fiona Tan, Gayathri Kaur Gill and Tony Leow from the National Library Board, Singapore. I would also like to thank Tim Yap Fuan, Gandimathy Durairaj, Donna Brunero and Tim Barnard from the National University of Singapore. Finally, I would like to extend my appreciation to my friends who helped me adjust to life in Singapore.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

“A New Phase of Commercial Expansion in Southeast Asia, 1760–1850.” In The Last Stand of Asian Autonomies: Responses to Modernity in the Diverse States of Southeast Asia and Korea, 1750–1900. Edited by Anthony Reid. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1997. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RBUS 330.95904 LAS)

Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir. The Voyage of Abdullah. Singapore: Malaya Publishing House, 1949. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.5 ABD)

Buckley, Charles Burton. _An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore, 1819–_1867. Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1984. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 BUC-[HS])

Crawfurd, John. History of the Indian Archipelago. Vol. 3. London: Frank Cass & Co., 1967. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 991 CRA)

Earl, George Windsor. The Eastern Seas: Or Voyages and Adventures in the Indian Archipelago in 1832–1834. London: Allen & Co., 1837. (From National Library Online)

Gibson-Hill, C. A. “The Master Attendants at Singapore, 1810–1867.” Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 33, no. 1 (May 1960): 1–64. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.5 JMBRAS-[JSB])

Graham, Walter Armstrong. Kelantan: A State of the Malay Peninsula. Glasgow: James Maclehose & Sons, 1908. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.593 GRA)

Holloway, C. P. Tabular Statements of the Shipping of Singapore, Prince of Wales’ Island, and Malacca for the Official Year 1862–63. Calcutta: Military Orphan Press, 1864.

Ibrahim Ariff and Andik Marinah Ibrahim. The Past Malay Entrepreneurs in Singapore. Singapore: Daing Pasandri Achiever Avenue, 2015. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 338.0409225957 IBR)

Jarman, Robert L. ed., Annual Reports of the Straits Settlements 1855–1941. Vol. 1. London: Archive Editions, 1998. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.51 STR-[AR])

Kathirithamby-Wells, J. “Siak and Its Changing Strategies of Survival, c. 1700–1870.” In The Last Stand of Asian Autonomies: Responses to Modernity in the Diverse States of Southeast Asia and Korea, 1750–1900. Edited by Anthony Reid. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1997. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RBUS 330.95904 LAS)

Khoo, Kay Khim. The Western Malay States, 1850–1873: The Effects of Commercial Development on Malay Politics. New York: Oxford University Press, 1972. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.5103 KHO)

The National Archives (United Kingdom). “Piracy in The Straits of Malacca.” Private records, 5 December 1828. (From National Archives of Singapore accession no. ADM 125/44; microfilm NAB 279)

Lohanda, Mona. The Kapitan Cina of Batavia, 1837–1942: A History of Chinese Establishment in Colonial Society. Jakarta: Djambatan, 1996. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.82004951 LOH)

Mackay, Colin. A History of Phuket and the Surrounding Region. Bangkok: White Lotus, 2012. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.3 MAC)

Milner, Anthony Crothers. Kerajaan: Malay Political Culture on the Eve of Colonial Rule. Petaling Jaya: Strategic Information and Research Development Centre, 2016. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.5103 MIL)

—. The Malays. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 305.89928 MIL)

Nordin Hussin. Trade and Society in the Straits of Melaka: Dutch Melaka and English Penang, 1780–1830. Singapore: NUS Press, 2007. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.503 NOR)

Phipps, John. A Practical Treatise on the China and Eastern Trade. London: W. H. Allen and Company, 1836.

Sampan-Pukat Trade to the Eastward. (1837, January 12). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG .

Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser. “Sampan-Pukat Trade to the Eastward.” 12 January 1837, 3. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Page 3 Miscellaneous Column 1: Imports… Exports.” 24 June 1841, 3. (From NewspaperSG)

Raffles Museum and Library. Straits Settlements Records Penang Consultations. Private records, 29 July 1825, 234. (From National Archives of Singapore accession no. A21; microfilm NL0008)

—. Straits Settlements Records Penang Consultations. Private records, 7 December 1826. (From National Archives of Singapore accession no. A30; microfilm NL0012)

Swettenham, Frank. British Malaya. London: John Lane, 1907. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RDKSC 959.5 SWE)

Thíphaakorawon, Cawphrajaa. The Dynastic Chronicle. Bangkok Era, the Fourth Reign. Vol. 2. Tokyo: Tokyo Press Co., 1965. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.3 CAW-[HYT])

Thomson, John. The Straits of Malacca, Indo China and China. London: Low, & Searle. (From National Library Online)

Turnbull, C. M. A History of Modern Singapore, 1819–2005. Singapore: NUS Press, 2009. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 TUR-[HIS])

Webster, Anthony. Gentlemen Capitalists: British Imperialism in South East Asia 1770–1890. New York: Tauris Academic Studies, 1998. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959 WEB)

Wright, Arnold. ed., Twentieth Century Impressions of British Malaya. London: Lloyd’s Greater Britain Publishing Co., 1908. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.51033 TWE)

NOTES

-

John Crawfurd, History of the Indian Archipelago, vol. 3 (London: Frank Cass & Co., 1967), 142. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 991 CRA) ↩

-

Anthony Crothers Milner, The Malays (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008), 53–55. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 305.89928 MIL) ↩

-

Milner, The Malays, 60–66. ↩

-

“A New Phase of Commercial Expansion in Southeast Asia, 1760–1850,” in The Last Stand of Asian Autonomies: Responses to Modernity in the Diverse States of Southeast Asia and Korea, 1750–1900, ed. Anthony Reid. (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1997), 65–66. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RBUS 330.95904 LAS) ↩

-

Reid, “A New Phase of Commercial Expansion in Southeast Asia, 1760–1850,” 63. ↩

-

C. P. Holloway, Tabular Statements of the Shipping of Singapore, Prince of Wales’ Island, and Malacca for the Official Year 1862–63. (Calcutta: Military Orphan Press, 1864), 122–23. ↩

-

Nordin Hussin, Trade and Society in the Straits of Melaka: Dutch Melaka and English Penang, 1780–1830 (Singapore: NUS Press, 2007), 119. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.503 NOR) ↩

-

Khoo Kay Khim, The Western Malay States, 1850–1873: The Effects of Commercial Development on Malay Politics (New York: Oxford University Press, 1972), 53. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.5103 KHO) ↩

-

Raffles Museum and Library, Straits Settlements Records Penang Consultations. Private records, 29 July 1825, 234. (From National Archives of Singapore accession no. A21; microfilm NL0008) ↩

-

Raffles Museum and Library, Straits Settlements Records Penang Consultations. 29 July 1825, 234–39. ↩

-

Milner, The Malays, 70–71. ↩

-

Crawfurd, History of the Indian Archipelago, 152. ↩

-

Crawfurd, History of the Indian Archipelago, 151–52. ↩

-

George Windsor Earl, The Eastern Seas: Or Voyages and Adventures in the Indian Archipelago in 1832–1834 (London: Allen & Co., 1837), 185. (From National Library Online) ↩

-

Earl, The Eastern Seas: Or Voyages and Adventures in the Indian Archipelago in 1832–1834, 185–86. ↩

-

“Sampan-Pukat Trade to the Eastward,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 12 January 1837, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Earl, The Eastern Seas: Or Voyages and Adventures in the Indian Archipelago in 1832–1834, 154. ↩

-

“Page 3 Miscellaneous Column 1: Imports… Exports,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 24 June 1841, 3 (From NewspaperSG); C. P. Holloway, Tabular Statements of the Commerce of Singapore, 1823–40 to 1839–40 (microform) (Singapore: Singapore Free Press Office, 1984), 47–49. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 380.1095957 SIN) ↩

-

John Thomson, The Straits of Malacca, Indo China and China (London: Low, & Searle, 1875), 17. (From National Library Online) ↩

-

Crawfurd, History of the Indian Archipelago, 185–86. ↩

-

Mona Lohanda, The Kapitan Cina of Batavia, 1837–1942: A History of Chinese Establishment in Colonial Society (Jakarta: Djambatan, 1996), 33, 53–54. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.82004951 LOH) ↩

-

Anthony Crothers Milner, Kerajaan: Malay Political Culture on the Eve of Colonial Rule (Petaling Jaya: Strategic Information and Research Development Centre, 2016), 35–37. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.5103 MIL) ↩

-

Milner, Kerajaan: Malay Political Culture on the Eve of Colonial Rule, 40–41, 44. ↩

-

Frank Swettenham, British Malaya (London: John Lane, 1907), 137. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RDKSC 959.5 SWE) ↩

-

Milner, Kerajaan: Malay Political Culture on the Eve of Colonial Rule, 72. ↩

-

Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir, The Voyage of Abdullah (Singapore: Malaya Publishing House, 1949) 9–10. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.5 ABD) ↩

-

Charles Burton Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore, 1819–1867 (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1984), 564. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 BUC-[HS]) ↩

-

C. M. Turnbull, A History of Modern Singapore, 1819–2005 (Singapore: NUS Press, 2009), 31–32. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 TUR-[HIS]) ↩

-

C. A. Gibson-Hill, “The Master Attendants at Singapore, 1810–1867,” Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 33, no. 1 (May 1960): 9–10. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.5 JMBRAS-[JSB]) ↩

-

Raffles Museum and Library. Straits Settlements Records Penang Consultations. Private records, 7 December 1826. (From National Archives of Singapore accession no. A30; microfilm NL0012) ↩

-

Robert L. Jarman, ed., Annual Reports of the Straits Settlements 1855–1941, vol. 1. (London: Archive Editions, 1998), 32. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.51 STR-[AR]) ↩

-

Jarman, Annual Reports of the Straits Settlements 1855–1941, 91. ↩

-

J. Kathirithamby-Wells, “Siak and Its Changing Strategies of Survival, c. 1700–1870,” in The Last Stand of Asian Autonomies: Responses to Modernity in the Diverse States of Southeast Asia and Korea, 1750–1900, ed. Anthony Reid. (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1997), 232–33. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RBUS 330.95904 LAS) ↩

-

John Phipps, A Practical Treatise on the China and Eastern Trade (London: W. H. Allen and Company, 1836), 293. ↩

-

Ibrahim Ariff and Andik Marinah Ibrahim, The Past Malay Entrepreneurs in Singapore (Singapore: Daing Pasandri Achiever Avenue, 2015), 31–32. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 338.0409225957 IBR) ↩

-

Colin Mackay, A History of Phuket and the Surrounding Region (Bangkok: White Lotus, 2012), 282–83. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.3 MAC) ↩

-

Cawphrajaa Thíphaakorawon, The Dynastic Chronicle. Bangkok Era, the Fourth Reign, vol. 2 (Tokyo: Tokyo Press Co., 1965), 423–25. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.3 CAW-[HYT]) ↩

-

The National Archives (United Kingdom), “Piracy in The Straits of Malacca,” private records, 5 December 1828. (From National Archives of Singapore accession no. ADM 125/44; microfilm NAB 279) ↩

-

Anthony Webster, Gentlemen Capitalists: British Imperialism in South East Asia 1770–1890 (New York: Tauris Academic Studies, 1998), 20. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959 WEB) ↩

-

Walter Armstrong Graham, Kelantan: A State of the Malay Peninsula (Glasgow: James Maclehose & Sons., 1908), 44. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.593 GRA) ↩

-

Ibrahim Ariff and Andik Marinah Ibrahim, The Past Malay Entrepreneurs in Singapore, 25; Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore, 1819–1867, 564. ↩

-

Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore, 1819–1867, 564; Arnold Wright, ed., Twentieth Century Impressions of British Malaya (London: Lloyd’s Greater Britain Publishing Co., 1908), 707. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.51033 TWE) ↩

-

Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore, 1819–1867, 564.84, p. 564. ↩

-

Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir, The Voyage of Abdullah, pp. 2, 15. ↩

-

Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir, The Voyage of Abdullah, 21. ↩

-

Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir, The Voyage of Abdullah, 43. ↩

-

Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir, The Voyage of Abdullah, 68. ↩