An Ethnohistory of Singaporean Javanese Diaspora In Nurturing Javanese Identity And The Roots

By Fuji Riang Prastow

Introduction

On 29 May 2016, the Javanese Association of Singapore (JAS) conducted the opening ceremony of the exhibition Pusåkå held at the Malay Heritage Centre. Posing for group photos in front of a Malay-style building on a typical day in Singapore were people dressed in full Javanese attire – women in kebaya (traditional blouse-dress) with batik sarong, and men in blangkon headdress complete with kris (a dagger with a wavy-edged blade). Pusåkå, meaning heirloom or legacy in Javanese, showcased the heritage and cultural history of the Javanese who settled in Singapore, as well as the ways in which they nurtured their Javanese identity. Pusåkå featured a diverse range of artefacts and everyday objects including a number of Javanese family heirlooms passed down from one generation to the next. During the exhibition’s opening speech, as reported by The Straits Times, Malay Heritage Centre curator Suhaili Osman said that Pusåkå was an excellent example of how we live and breathe heritage in our daily lives sometimes without realising it (Kao, 2016).

Besides Pusåkå, seminar sessions were also organised, including a special discussion on the roots journey conducted by Singaporean-Javanese Nori Norindah Joyhana Ahmad, author of The Roots of My Ancient Journey. Nori’s self-published book recounts a Singaporean-Javanese’s journey of self-discovery and her experience on reconnecting with her Javanese ancestral roots. After experiencing this journey, Nori began to nurture her Javanese identity more seriously.

The roots journey is a massive phenomenon experienced by Singaporean- Javanese living in the diasporic condition. These Singaporean-Javanese are often interested in the romanticism of Javanese history and journeying to

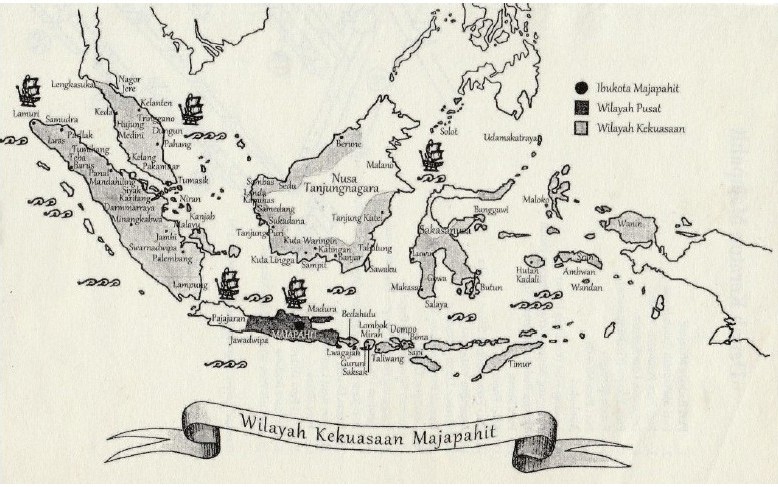

Java, Indonesia in search of their roots. They trace their ancestry in Java according to oral history or historical documents that have been and are still handed down through generations. By going on a roots journey to Java, they can cultivate more historical stories about Singapore from the Javanese perspective. For many of them, this journey represents how they can nurture their ancestral heritage and cultivate their identities as Javanese. This phenomenon is intertwined with the history of the Javanese in Singapore when Tumasik (Singapore’s ancient name) was one of the vassals of the Javanese-Majapahit empire, as recorded in 14th century Javanese annals Nagarakrtagama and Pararaton (Kriswanto, 2009:106; Riana, 2009:99). This has also been supported by archeological evidence1 of jewellery typical of the Javanese-Majapahit kingdom unearthed around Bukit Larangan (present-day Fort Canning in Singapore) (Kwa, Heng and Tan, 2009:14; Miksic and Gek, 2004:17). This begets the question of how Singaporean-Javanese can nurture Javanese cultural heritage in their daily lives in Singapore, and how this would in turn encourage them to go on a roots journey to Java.

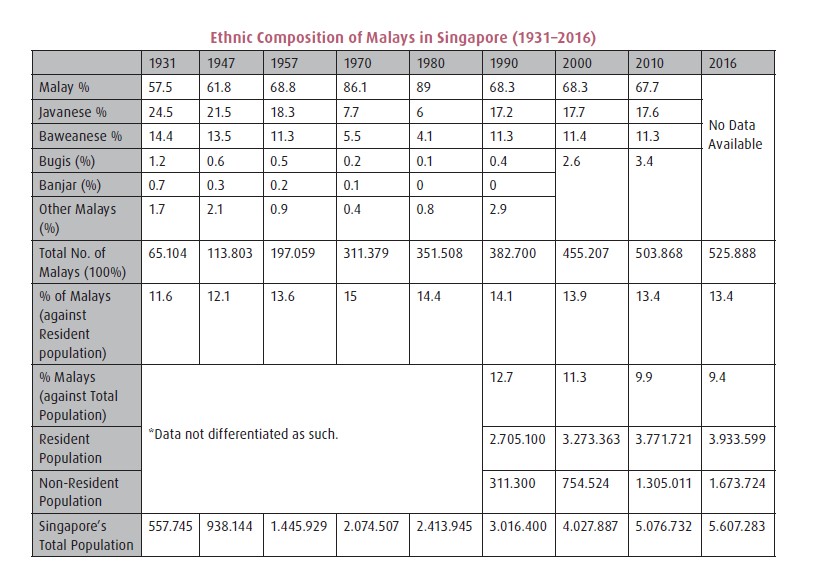

In the 2010 census of Singapore, 88,646 Singaporeans identified themselves as “Javanese” (Singapore Department of Statistics, 2010:46). However, many Singaporeans are still unaware of the history of the Javanese in Singapore. The Javanese have been present in Singapore since the Majapahit empire, when Singapore (then known as Tumasik) had been its vassal according to the royal court poem of Nagarakrtagama written in 1365 (Anshory and Arbaningsih, 2008:84; Purwadi, 2005:12; Poesponegoro and Notosusanto, 1992:92; Robson, 1995:35). Javanese mass migration continued after the arrival of the British in the early 19th century. In short, there have been four main phases of Javanese migration in Singapore: the Nusantara ancient era of Tumasik, the British colonial era, the Japanese Occupation era and the modern era of Singapore.

As such, it might be surprising to some that there is little literature examining the Javanese in Singapore, and what exists are student theses, such as: “The Javanese of Singapore” by Abdul Aziz bin Johari (University of Malaya, 1961), “The Baweanese and the Javanese in Singapore: A Comparative Analysis of Integration in a Plural Sociology by Juliana Khusaini (National University of Singapore, 1989) and “A History of the Javanese and Boyanese in Singapore” by Hwee Hwee Jeanette Chia (National University of Singapore, 1992). Despite the existence of such theses, there are no published books on the subject. Moreover, little has been said about the contemporary movement in the form of the roots journey undertaken by Singaporean-Javanese. This study thus seeks to bridge the gap in Singapore’s knowledge about the Javanese in Singapore.

Ethnohistory combines the approaches of history, philology, cultural anthropology and archaeology (Calloway, 1983:97; Carmack, 1972:230; Chavez, 2008:487; Gadacz, 1982:148). Ethnohistory, in short, is based on historical documents, but are written with anthropological insight (Harkon, 2010:113; Sluis and Edwards, 2013:72, Wood, 1990:81). By combining historical and ethnographic approaches according to Fontana (1961:10), this ethnohistorical study will examine historical data through empirical facts in the field. The historical explanation in this paper can be positioned as an integral part of understanding the dynamic picture of the development of the Javanese in Singapore.

In the case of diasporas, the romantic memory of ancestors is the main pillar of nurturing a distinctive identity and strengthening the diaspora’s sense of belonging to their ancestral homeland. In the context of the Singaporean- Javanese, the Javanese identity is built upon two main elements: the history of the Javanese in Singapore and the way Javanese culture has been assimilated into the Malay culture in Singapore. Nurturing the Javanese identity in Singapore, which is “unique” compared to being Javanese in Java, compels the Singaporean-Javanese go on a roots journey to Java, motivated not only by the desire to trace their roots but also to reminisce about Java’s history in Tumasik in the context of Singapore.

Crafted from something new and rereading existing historical sources, this study attempts to present an alternative perspective of the Javanese in Singapore and examine how the roots journey is nurtured by analysing two aspects: identity and history. This paper is centred around these two aspects, explaining history and identity as integral parts of understanding the roots journey undertaken by the Singaporean-Javanese diaspora.

Navigating Diaspora and the Notion of Homeland

In many studies, diaspora is linked to the notion of homeland (see e.g. Basu, 2007; Clifford, 1994; Cohen, 2008; Falzon, 2003; Knoot and McLoughlin, 2010; Levy and Weingrod, 2005; Morawska, 2011; Rozen, 2008; Sheffer, 2010; Tololyan, 2007). Levy and Weingrod (2005:3) reveal that home in this context is much more than a physical structure (a house), but also an imagined place with a set of feelings and imaginative realms. Home is a process of creating and understanding forms of living and belonging. This means home can evoke a sense of belonging, a memory of the past and variable emotions. As a result, links with the ancestral homeland are often decorative and deeply embedded in memories of diasporic people (Clifford, 1994:304). Falzon (2003:664) states that homeland is generally understood as a sacred place filled with forms of longing and memory, either about culture or ancestors, and diasporic people dislocated from their homeland will maintain their imagined-homeland “by making a new home” while living in their host countries. According to Tölölyan (2007:649), the continuation of home-maintaining can be performed by commemorating and reconstructing a collective identity that preserves elements of the homeland’s language, religion, social practice and cultural heritage.

In this study, the ethnographic data shows that the historical explanation of the Javanese in Singapore since the 12th to 14th centuries (according to archaeological remains found in Singapore) is part of the foundation of nurturing Javanese identity and maintaining links with their homeland by means of cultural preservation. Subjects we interviewed affirmed the importance of this to them:

“…reminiscing the history of the Javanese in Singapore when it

was a Javanese-Majapahit vassal is our pride of [being] Javanese

in a place where Gadjah Mada (a Majapahit prime minister who

united Nusantara by means of Palapa expedition) was here…”

Interview with Sri Sulistiyanti

Orchard Road, Singapore

21 April 2018

Many Singaporean-Javanese share Sri’s (a third generation Singaporean- Javanese) sentiment – the romanticism of the ancient history of the Javanese in Tumasik is a part of respecting their ancestors and understanding the lineage of Javanese migration to Singapore to the present day. From that story, it can be inferred that the oral tradition is the foremost method in transmitting stories of one’s roots in human culture. Supporting this idea is existing literature that states that remembering ancestors is a basic part of human culture (Fairley, 2003; Geana, 2005; Levitt, 2010; Schenider, 2008;, Schraam, 2010). Generally, tales about one’s ancestors are passed down through the generations through storytelling, at least within families. Among the Singaporean-Javanese, there are several stories that are recalled and shared, such as the story of Javanese Singhasari-Majapahit kingdoms in Tumasik, the story of ancestral migration during Islamic Hajj during the colonial era, the story of being Javanese and Malay, and the story of reconnecting with one’s roots.

According to Geana (2005:349), one of the most ancient and elaborate cultural acts is the devotion of the ancestral cult by remembering and also worshipping the deceased, the so-called memorialisation of ancestors that answers a fundamental need of humans – the need to remember. This can be done by recalling a story of origins that employs genealogies of human history (Schraam, 2010:23). According to Schenider (2008:2), telling stories is how people construct meaning from memory, but the process is selective and many factors influence which stories are told. Repeating stories of and about ancestors, or so-called Ngeling-eling in the Javanese language, is one of the pillars of Javanese culture. Repeating ancestral stories is also linked to a search for selfhood for diasporic people. Ngeling-ngeling can be deduced as a part of cultivating Javanese identity and maintaining Javanese heritage. This can be done by several modes: retelling stories of one’s roots, as well as cultivating and finding one’s roots.

This is in line with the wise Javanese saying: “Javanese people without the knowledge of their past history is [sic] like a tree without roots, koyo kacang lali kulite (such as a peanut forgetting its nutshell)”. This is what Arora and Sanos (2011:91) call the melancholia of diaspora, where the diasporic imagination is filled with stories of loss, past memories and recalling history. In the case of Singaporean-Javanese diaspora, recalling a story of ancestors can be done by referring to the archeological evidence found at Bukit Larangan that shows the Javanese Singhasari- Majapahit civilisation in Tumasik as well as modern migration during the colonial era.

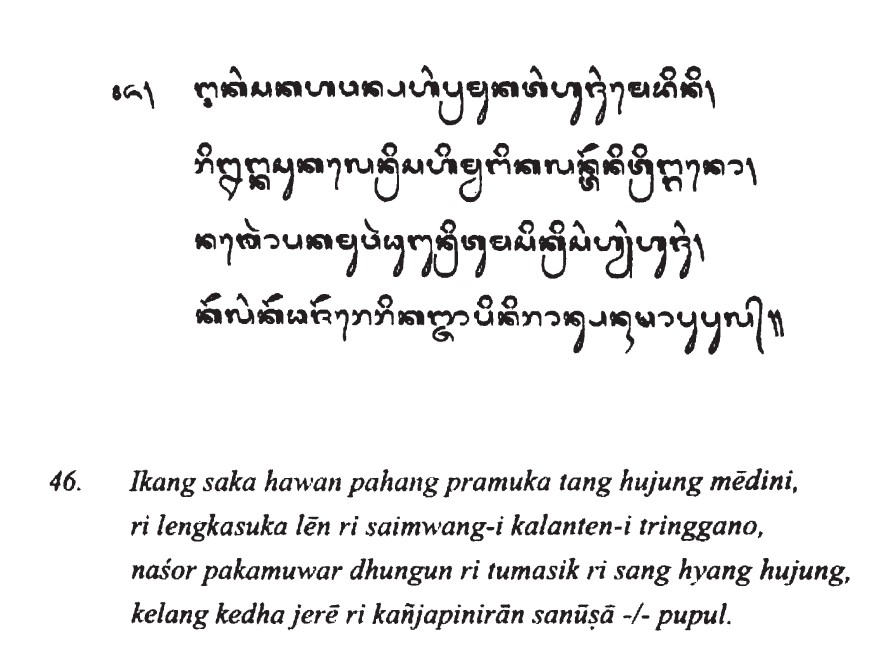

In fact, the archaeological evidence comprising Javanese-Majapahit jewellery, unearthed during excavations in Bukit Larangan between 1926 and 1928, indicates that Javanese civilisations existed in Singapore since the 14th century (Anne and Lim, 2017:4; Bastin, 1994:5 Kwa, Heng and Tan, 2009:14; Miksic and Gek, 2004:17; Turnbull, 1989:19; Yeo, 2017:24). According to a verse in Nagarakrtagama2 written in Kawi, an ancient Javanese language (Riana, 2009:99),3 Tumasik was a vassal of the Javanese-Majapahit kingdom (Robson, 1995:2).

In line with Nagarakrtagama, Singapore is also mentioned in the majestic pledge4 of Gadjah Mada during his inauguration as Majapahit Amangkubhumi (prime minister) in 1336 CE (Hazra, 2007:40). In addition, in 1275 CE (prior to the Majapahit period), Kertanegara from the Singhasari kingdom invaded Malayu under the Pamalayu expedition as narrated in Pararaton and Nagarakertagama after Kertanegara’s great victory in attacking Jambi and Palembang (Adji and Achmad, 2013:94; Barwise and White, 2012:69; Blagden, 1909:23; Hall, 1960:67; Munoz, 2006:262; Ricklefs, 2001:22; Rouffaer and Winstedt, 1922:56). The Pamalayu expedition in 1187 caka, or 1275 CE, is also mentioned in the texts Pararaton, Kidung Panji Wijayakrama, Kidung Harsawijaya and Nagarakrtagama pupuh 41 (Muljana, 2011:112-113).

Written historical records depicting the Javanese civilisation in Singapore after the decline of Majapahit are scarce.5 Singapore was subsequently governed under the reign of the Johore-Riau-Lingga Sultanate (Rahim, 2006:521).6 When Raffles arrived in Singapore, there were already indigenous people, including Malays living in kampongs (villages) and Orang Laut (sea gypsies comprising the Orang Kallang, Orang Seletar/ Slitar, Orang Selat and Orang Gelam), living around the mouth of the Singapore River, Kallang River, Telok Blangah and along the Johor Straits (Diagana and Angresh, 2013:21).

The story of the Javanese in Tumasik can be considered as the pride of Singaporean-Javanese in modern Singapore, representing the spirit of exploration of the Javanese in modern Singapore. The story of the Javanese during the Majapahit and Singhasari eras in Tumasik also underscores the importance of commemorating simbah (literally translated as ancestors in Javanese) as part of nurturing ancestral roots and cultivating Javanese identity.

Nurturing Javanese Identity in the Malay Community

Most discussions of diaspora are firmly rooted in the concepts of homeland and identity (see e.g. Arora and Sanos, 2011; Brienkerhoff, 2009; Drzewiecka, 2002; Esman, 2009; Oonk, 2007; Peachey, 2011; Safran, 1999; Zhao, 2008). One difficulty with the use of the word “identity” is that different disciplines use the term to mean different things. According to Peachey (2011:14), the term “identity” within diaspora studies is concerned with the sense of a people’s conceptualisation of self; the ways in which people subjectively perceive or experience themselves in host societies through names, labels and identification. From Peachey, it can be inferred that diasporic people need to actualise themselves with specific names, labels and identification. Hence, Singaporean society may recognise the existence of Singaporean-Javanese within the Malay community through their adherence to the Javanese identity.

To support the argument, this section elucidates some of the existing literature that describes the preservation of cultural heritage and identity. Levitt (2010:42) reveals that diasporic people strongly reinforce homeland ties by cultivating “the identity of origin”. Supporting Levitt, Allen (2013:3) says that to cultivate the identity of origin, diasporic people establish and reaffirm their ethnic identity in new places by reconstructing an imagined homeland. Other arguments related to theoretical concepts are that nurturing one’s historical ethnic background is important for diasporic people to commemorate ancestral memories (Leong, 2014; Marschall, 2013), to cultivate ancestral identity (Bhandari, 2013; Naho and Stronza, 2010; Marschall, 2014), and to romanticise “a home identity” (Bandyopadhyay, 2008; Man, 2014). Therefore, in this section it can be argued that by maintaining Javanese cultural heritage within the Malay

community, Singaporean-Javanese also strengthen their identities as Javanese.

At present, the Javanese in Singapore are often linked to the Malays. In Singapore’s national context, Malay is used as a race category by the government and as an ethnic group referring to the indigenous people of Singapore (Ibrahim, 2014:2; Rahim, 2006:521). According to Suryakencana Omar, head of the Javanese Association of Singapore (JAS), the earliest historical data [as noted by Amin (2017:215–216)] of contemporary Javanese in Singapore dates back to the 1820s.7

The 1980 population census states that the Malay include all persons of Malay or Indonesian origin such as Malays, Javanese, Boyanese and Bugis, by means of a patrilineal system (Amin, 2017:200).

To minimise social conflict among the early immigrants in Singapore, Raffles, along with his government, formulated a town plan (also called the Jackson Plan) in 1822 to divide residential land based on the different races in Singapore (Anne and Lim, 2017:24). These ethnic-based areas were assigned names such as Kampong Java and Kampong Bugis.8

Over time, close interactions and shared religious values among immigrant communities resulted in the Javanese being labelled as Malay. This made it difficult for the Javanese identity to stand alone, as shared by Suryakencana Omar:

“Being Javanese among the Malay community in Singapore is not

an easy task as we [have to] work much harder in nurturing our

identity than the Javanese in Java, who have a ‘taken for granted

identity’ from the ancestors.”

Interview with Suryakencana Omar

Malay Heritage Centre, Singapore

24 February 2018

Although many Singaporean-Javanese no longer speak Javanese in their daily lives, they still preserve their heritage in their own way. Crang (2010:139) argues how food can connect people to personal and social memories of their homeland. The well-known dish nasi ambeng, for example, is an integral part of the Selametan or Kenduri. Dishes that Singaporeans might be familiar with but are unaware are Javanese include soto, satay, nasi rawon and tempe. According to the Singaporean-Javanese diaspora, their links to Javanese cuisine, albeit adapted to suit local tastes with influences from Malay, Indian and Chinese cuisines, is one of their most important, particularly when set within the Malay community. Therefore, diverse Javanese foods are still consumed among Singaporean society. Singaporean-Javanese Haider Surya noted that many Javanese dishes such as nasi ambeng, satay and tempe have been commercialised and distributed around Singapore. This reproduces the Javanese identity as Singaporean-Javanese are able to easily access authentic Javanese food in Singapore.

Cuisine aside, there are many intangible Javanese cultural arts found in Singapore such as dance, pencak silat (martial arts), gamelan (traditional ensemble music originating from Java and Bali), jamu, keris and kuda kepang. To preserve Javanese heritage in Singapore, several organisations have been established, such as Kesenian Tedja Timur/Kuda Kepang (established in 1991), Sri Warisan (wayang kulit Singapore/Javanese puppet show founded in 1997), Perguruan Silat Kembang Wali (pencak silat group), Perguruan Seni Beladiri Tapak Suci Singapura (pencak silat group), Pacitan Gamelan (founded in 1991 at the Kembangan Community Club), Singa Nglaras at the Department of Southeast Asian Studies in

the National University Singapore (established in 2004) and Gamelan Asmaradana Ltd (founded in 2004). The first organisation for the Javanese in Singapore was Persekutuan Jawa Al-Masakin (loosely translated as the Federation of the Javanese Poor), which was formed in 1901 to provide material and moral support to Javanese who had moved to Singapore.

In late 2007, with the popularity of social media platform Facebook, three Facebook groups – “Javanese Singaporeans”, “Singaporean Javanese” and “Orang Jawa in Singapore” (Javanese in Singapore) – were set up. The following year, the groups merged to become “Javanese Singaporeans (JS): Orang Jawa di Singapura”. It should be noted that the Javanese Association of Singapore (JAS), which was formed by members of informal groups such as Perkumpulan Anak Jawa Pacitan, Kesenian Tedja Timur and the Javanese Singaporeans Facebook groups, had evolved from online entities into a legally registered “society” organisation on 10 September 2015. An example of concrete action in preserving Javanese culture is the hosting of the May 2016 exhibition “Pusaka: Heritage and Culture of the Javanese in Singapore” (Chew, 2016; Kao, 2016). This validates the claim that the Singaporean- Javanese continue to nurture their identity today.

Javanese identity is articulated not only at the individual level, but also collectively framed into perkumpulan (organisations). Referring to Duarte

(2005:316), diaspora is similar to collectivism, in which collective identity can be reconstructed by several processes and practices shared by members of a diaspora in a host country. This is to say that solidarity is the main way to build a strong social community (Christenen and Levinson, 2003:134). In addition, Drzewiecka (2002:2) suggests that diasporic people struggle to reconstitute collective identities by reproducing their familiar environment among them. In a collective society, they can enjoy the fellowship and relationships with members who share the same culture, sustain the same tradition, eat the same food and speak the same language. Generally, the Javanese have a strong culture of communalism. Huggan (2010:56) argues that diaspora identities are those that are constantly producing and reproducing themselves through transformation and difference. Hence, the existence of community can be considered as the power of representing and strengthening group identity for Singaporean-Javanese so as to differentiate themselves from other Malay groups.

This is to say that the theoretical framework of heritage comprises not only sites, places, performances or events, but also social construction and cultural practice, hence drawing attention to the process of heritagemaintenance. This supports the construction of home as the remembrance of the past, present and future. “Home is where the heart is” is a phrase uttered by many who have experienced migration and displacement. In this context, the Singaporean-Javanese construct the “home of Java” but in a unique way that is influenced by Malay culture. Thus, “in-betweenness” is the way Singaporean-Javanese embrace the identities of being simultaneously Javanese and Malay. This sentiment is reflected by Zuraidah Ehsan:

“In-betweenness is not a bad thing for us [Singaporean-Javanese],

it has become the uniqueness of the Singaporean-Javanese diaspora

in being able to adapt to a place where we are living now, in the

Malay area. Being Malay does not mean we forget our roots

as Javanese.”

Interview with Zuraidah Ehsan

Paya Lebar, Singapore

18 January 2018

So, who are the Malays?9 The Malays are the indigenous people of Singapore, comprising 13.4 percent of Singaporean society, making them a minority (Rahman, 2017:1). As the Report of the Select Committee on Parliamentary Elections (Amendment) Bill of 1998 declared inter alia: “A person belonging to the Malay Community means any person, whether of the Malay race or otherwise, who considers himself/herself to be a member of the Malay community and who is generally accepted as a member of the Malay community by that community.” (Tham, 1992:11) Because of the importance of the 1998 Bill, the political view of Malays in Singapore implies that the definition of being Malay is not only based on biological inheritance but also from a self-defined or sense of belonging in being Malay.

The role of Islam also provides a meeting point for Javanese and Malay identities since universal values in Islam are a powerful factor that facilitates assimilation in terms of religious rituals, trade, education and marriage. In this case, Malay values have been exchanged and strengthened by the education system where generations of Javanese or other tribes from the Nusantara archipelago have sent their children to Malay schools. Therefore, the Malay identity would have been formally practiced in education, the religious environment, as well as interracial marriage. However, the Javanese identity remains sustainable in the smallest environment – the family. Javanese identity can be strengthened through the family by inculcating children with Javanese manners, teaching members about Javanese cuisine and speaking Javanese. Some families in Singapore deliberately send the younger generation to Java to immerse them in Javanese culture. Given this definitional fluidity, it follows then that a Javanese who assumes a Malay identity has not lost their ethnic identity but has come to see themselves as simultaneously Javanese and Malay.

On another level of analysis, the preservation of Javanese ancestral heritage for the purpose of nurturing the Javanese identity conducted by the Singaporean-Javanese has a strong correlation to the reasons that encourage them to travel to Java. Travelling to Java can be considered a significant effort to preserve Javanese cultural heritage by networking with local people in one’s ancestral homeland, sharing stories with Java-born Javanese, exchanging views with Javanese cultural experts, studying the development of Javanese culture in Java for application in Singapore, cultivating Javanese identity, and much more. Therefore, it can be said that the roots journey and preservation of Javanese culture are interrelated.

Emerging Trends of the Roots Journey

In line with earlier arguments, it can be argued that the preservation of the memory of ancestors by reconstructing the “home” and maintaining Javanese cultural heritage as a form of representing their identity encourages Singaporean-Javanese to go to Java on a roots journey. The internet, especially Facebook, is essential in facilitating global interaction among Javanese diaspora, which can strengthen the Javanese identity among Singaporeans. Like other Javanese diaspora, the Singaporean-Javanese try to strengthen their Javanese identity by contacting Javanese in Java via social media platforms to find out the latest issues concerning their culture. This leads them to undertake the roots journey by tracing the history of their ancestors. This is why discussing the contemporary Singaporean-Javanese identity cannot be separated from the roots journey phenomenon. Their experiences either on Facebook or in Java produce global relationships with other Javanese diasporas elsewhere. It reveals the cycle of migration that results in the return to ancestral lands and a new facet in their identity.

“As a retired person, I [went] on a roots journey around Tuban in

East Java where my father came from. My father travelled alone

from Java to Singapore around the 1920s when he was 17 years old

and ended up here for the rest of his time because someone stole

his luggage, including his money and passport. Unfortunately, as

Orang Atas (a notable and educated Javanese person), he never

clearly revealed who he was until he died. This mystery strongly

motivates me to go on a roots journey again and again.”

– Interview with Sujono

Jurong, Singapore

25 February 2018

As a Singaporean-Javanese, Sujono considers himself like a sturdy tree whose branches and flowers blossom in Singapore, but whose roots are still firmly planted in his ancestral island of Java. This is the most popular metaphor among the diaspora. Sujono experienced the roots journey in Java by following an ancestral path from the village where his grandfather had been born in Tuban, to the harbour where his ancestors had left Java forever.

There is a myriad of literature on the phenomenon of members of diasporas travelling to their homelands for nostalgic tourism (Mitchell, 1998), homeland tourism or homeland journeys (Bandyopadhyay, 2008; Iorio & Corsale, 2013), ancestral tourism (Bhandari, 2013; Man, 2014; Leong, et.al, 2014; Russell, 2008), homesick tourism (Marschall, 2014) and roots tourism (Basu, 2005; Pinho, 2008; Naho and Stronza, 2010). The roots journey seeks some form of remedy of memories to commemorate ancestral histories (Leong & et.al, 2014; Prastowo, 2017), to trace their ancestral sites in the homeland (Dubuisson & Genina, 2011; Kuutma, 2013), and to remember ancestral routes in the process of becoming diasporic people (Iorio and Corsale, 2013; Marschall, 2013; Pinho, 2008). The roots journey is an example of how Singaporean-Javanese nurture their ancestral roots by travelling to their homeland in Java.

The importance of finding one’s roots strongly underscores how essential ancestral roots are to the Singaporean-Javanese, because remembering roots is one of the pillars of Javanese culture. Generally, Singaporean-Javanese trace their ancestry in Java according to oral stories or historical documents that were handed down through the generations. Like Sujono, most of them follow the path from the village in Java where their ancestor was born to where (usually the harbour) they had left Java. When in Java, the atmosphere of rural life and engaging in small talk with the locals, reaffirms and rejuvenates the Singaporean-Javanese’s identity as Javanese. The results of travelling to Java vary depending on how travellers feel post-travel.

Social media provides a platform for diverse virtual interactions between the Javanese diaspora and Javanese in Java. Often, Javanese diaspora meet on Facebook and share the experiences of their roots journey – for instance, on Facebook group Ngumpulke Balung Pisah (loosely translated as gluing separated bones together).10 These virtual interactions eventually led the Javanese diaspora from around the globe, including Singaporean- Javanese, to organise the first conference of the Javanese Diaspora in Yogyakarta, called Ngumpulke Balung Pisah (Kurniawan, 2015), on 15 and 16 August 2015.

The Singaporean-Javanese have played an important role not only as participants but also as founders of the worldwide organisation, whose long-term vision is to preserve Javanese cultural heritage around the globe. At present, reflecting on the international interactions among the Javanese diaspora across the globe, either in the virtual or physical realms, can encourage the Singaporean-Javanese to strengthen their distinctive identity as Javanese in Singapore rather than Malay, as Malay is an unfamiliar concept for Javanese diaspora living outside of the Nusantara archipelago (such as in Suriname, New Caledonia, the Netherlands and parts of the Caribbean). It supports reflections on “what should be Javanese” by means of mutual dialogue.

As Java is a short trip from Singapore, supported by many affordable flights to Jakarta, Yogyakarta and Surabaya, the roots journey has become essential for all Singaporean-Javanese. This journey is an integral part of strengthening Javanese identity among the Singaporean-Javanese today.

Conclusion

Coming back to the question that is the essence of this paper – how do Singaporean-Javanese nurture their identities by preserving Javanese cultural heritage in their daily lives in Singapore, and how does this encourage them to undertake the roots journey to Java? There are, of course, no easy explanations. This question elicits diverse responses depending on the definition of social identity, because identity is never static and always responds to socio-political developments of the present-day. Identity is a complex, even slippery, concept, shaped by history, culture and imagination (Pang and Meyer, 2016:2). Social identity, indeed, focuses on shared social characteristics (Mutalib 2012:12; Ratnasingam, 2010:4). To conclude, social identity nurtured by the Singaporean-Javanese emphasises shared aspects of identity, of being Malay without forgetting one’s Javanese roots. As having a dual identity is common in all societies, a Singaporean can be Malay and yet Javanese at the same time. There was once a clear distinction between Malay and other Nusantara ethnic groups. However, over time, through intermarriage, social interaction, education and policy, a new social identity was built as a Malay community shaped by religion, customs and language. In an individual context, the self-identification of being Javanese is important to the reinforcement of the homeland of Java in Singapore.

Present-day Singaporean-Javanese are by and large shaped by their past, which is supported by many archeological corroborations relating to Javanese civilisation in Singapore around Bukit Larangan and the Singapore River. But one thing is very clear: revisiting history is necessary to bridge the question of being Singaporean-Javanese. Since mobility can be considered a central part of Javanese DNA, this study thus concludes that the history of Javanese migration to Singapore can be summarised into four periods: First, during the Nusantara era (whether under Singhasari, Majapahit or even long before that such as Srivijaya and ancient Mataram); Second, during the British colonial period; Third, during the Japanese Occupation or Syonan-to period; and fourth, during the present-day modern state of Singapore – by which time (as recorded by the Indonesian National Agency of the Placement and Protection of Migrant Workers, or BNP2TKI), 13,379 Indonesians were employed as migrant workers in Singapore (as of 2018), most of whom were Javanese. This shows that the migration of the Javanese to Singapore has spanned hundreds or maybe even thousands of years.

In a nutshell, the preservation of “home” implies identity and leads diaspora to undertake the roots journey or “homecoming”. The reconstruction of a Java home among Singaporean-Javanese people may refer to the relationships or connections over space and time to their imagined homeland in Java, harmonised within the context of Singapore. Through the preservation of Javanese cultural heritage in Singapore, the Singaporean- Javanese can continue to pass down the stories of their ancestors to the present-day to nurture Javanese identity. This is viewed in terms of how Singaporean-Javanese people define and represent themselves as Javanese, because by having a strong emotional attachment to their homeland and constructing their identities as Javanese, they are probably more motivated to preserve their ancestral cultural heritage in Singapore, especially in Malay society. In short, the existence of Singaporean-Javanese with all their uniqueness in syncretizing Javanese and Malay cultures strengthens the colour of multiculturalism in Singapore.

To a large degree, and for future research, this study should be continued by those who are interested in working with the history of the Javanese in Singapore, as this paper only scratches the surface of the missing link in the narrative of Singapore’s national history.

Acknowledgments

I would like to extend a special thanks to Professor Dr. Irwan Abdullah, an anthropologist at Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia and expert on Nusantara diaspora, for reviewing this essay and providing his input.

REFERENCES

Adji, Krisna Bayu and Sri Wintala Achmad. Sejarah Kejayaan Singasari Dan Kitab Para Datu: Menyingkap Singasari Berdasarkan Fakta Sejarah [The history of Singasari’s success and the book of the datus: Revealing Singasari based on historical facts]. Yogyakarta: Araska Publisher, 2013. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Malay RSEA 959.828 ADJ)

Ageeth, Sluis and Elise Edwards, “Rethinking Combined Departments: An Argument for History and Anthropology,” Learning and Teaching: The International Journal of Higher Education in the Social Sciences 6, no. 1 (Spring 2013): 72–88. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Agung Kriswanto. Pararaton. Jakarta: Wedatama Widya Sastra, 2009. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Malay RSEA 899.2221 PRA)

Aidi Abdul Rahim. “The Nusantara Ethnic Communities of Singapore –Javanese, Baweanese, Minangs, and Banjarese.” In Majulah!: 50 Years of Malay/Muslim Community in Singapore, edited by Zainul Abidin Rasheed and Norshahril Saat. Singapore: World Scientific, 2016, 519–32. (From National Library Singapore call no. RSING 305.6970959R57 MAJ)

Allen, Pamela. “Diasporic Representations of the Home Culture: Case Studies From Suriname and New Caledonia.” Asian Ethnicity 16, no. 3 (December 2013): 1–18.

Anshory, H. M. Nasruddin and Arbaningsih. Negara Maritim Nusantara: Jejak Sejarah Yang Terhapus [Archipelago Maritime Countries: Erasing Traces of History]. Yogyakarta: Tiara Wacana, 2008.

Arora, Anupama and Sandrine Sanos, “Bhangra Blues: Melancholy, Memory, and History in Gurinder Chadha’s I’m British But ….” Journal of Postcolonial Writing 47, no. 1 (2011): 89–100.

Azhar Ibrahim. Narrating Presence: Awakening From Cultural Amnesia. Singapore: Malay Heritage Foundation, 2014. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 305.8992805957 AZH)

“Data Penempatan dan Perlindukan Tenaga Kerja Indonesia (TKI) Periode Bulan Desember Tahun 2017” [Indonesian Workforce Placement and Protection Data (TKI) for December 2017]. Badan Nasional Penepatan Dan Perlindungan Tenaga Kerja Indonesia (BN P2TKI), December 2017.

Bagus Kurniawan. “Berbagai Kisah Saat Keturunan Jawa Saling Bertemu dalam Javanese Diaspora” [Various stories when javanese descendants meet each other in the javanese diaspora], DetikNews, 15 August 2015.

Balfour, Edward, ed. Cyclopædia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia, Commercial, Industrial and Scientific. Madras: Printed at the Scottish & Adelphi presses, 1873. (From National Library Singapore, call no. SBG 954 CYC)

Bandyopadhyay, Ranjan. “Nostalgia, Identity and Tourism: Bollywood in the Indian Diaspora.” Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 6, no. 2 (September 2008): 79–100.

Bastin, John. Travellers’ Singapore: An Anthology. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1994. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.5705 TRA-[HIS])

Basu, Paul. “Roots Tourism As Return Movement: Semantics and the Scottis Diaspora.” In Emigrant Homecomings: The Return Movement of Emigrants, 1600–2000, edited by Marjory Harper. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2005.

–––. Highland Homecomings: Genealogy and Heritage Tourism in the Scottish Diaspora. London: Routledge, 2007.

Barwise, J. M. and Nicholas J. White. A Traveller’s History of South East Asia. London: Cassell, 2002. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959 BAR)

Bhandari, Kalyan. “Imagining the Scottish Nation: Tourism and Homeland Nationalism in Scotland.” Current Issues in Tourism 19, no. 1 (2016): 1–18.

Blagden, C. O. “Notes on Malay History.” Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 53 (September 1909): 139–161, 62. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Brinkerhoff, Jennifer M. Digital Diasporas: Identity and Transnational Engagement. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Brown, John W. World Migration and Labour. Amsterdam: Bureau Centrale Informatie van Het Emigratiebestuur, 1926.

Calloway, Collin G. “In Defense of Ethnohistory.” Journal of American Studies 17, no. 1 (April 1983): 95–99. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Carmack, Robert M. “Ethnohistory: A Review of Its Development, Definitions, Methods, and Aims,” Annual Review of Anthropology 1 (1972): 227–46. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Chaves, Kelly K. “Ethnohistory: From Inception to Postmodernism and Beyond.” Historian 70, no. 3 (Fall 2008): 486–513. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Chew, W. L. “Exploring Heirlooms of the Singapore-Javanese Community.” Channel NewsAsia, 10 June 2016. (From Factiva via NLB’s eResources website)

Chia, Jeanette Hwee Hwee. A History of the Javanese and Boyanese in Singapore. Singapore: NUS, 1992). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 305.89928095957 CHI)

Chia, Priscilla and Trenton James Riggs. “We, the Citizens of Singapore.” In Within & Without: Singapore in the World; The World in Singapore, edited by Pang Eng Fong and Arnoud De Meyer. Singapore: Singapore Management University, 2016. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 WIT-[HIS])

Christensen, Karen and David Levinson, ed., Encyclopedia of Community: From the Village to the Virtual World. California: Sage Publications, 2003. (From National Library Singapore, call no. R q307.03 EN C)

Clifford, James. “Diasporas.” Cultural Anthropology 8, no. 3 (August 1994): 302–8. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Cohen, Robin. Global Diasporas: An Introduction. London: Routledge, 2008.

Crang, Philip. “Diasporas and Material Culture.” In Diaspora: Concepts, Intersections, Identities, edited by Kim Knott and Sean McLoughlin. England: Zed Books, 2010, 139–244.

Diagana, Melissa and Jyoti Angresh. Fort Canning Hill: Exploring Singapore’s Heritage and Nature. Singapore: ORO editions, 2013. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 DIA-[HIS])

Drzewiecka, Jolanta A. “Reinventing and Contesting Identities in Constitutive Discourses: Between Diaspora and Its Others.” Communication Quarterly 50, no. 1 (2002): 1–23.

Duarte, Fernanda. “Living in ‘The Betweens’: Diaspora Consciousness Formation and Identity Among Brazilians in Australia.” Journal of Intercultural Studies 26, no. 4 (2005): 315–35.

Dubuisson, Eva-Marie and Anna Genina. “Claiming an Ancestral Homeland: Kazakh Pilgrimage and Migration in Inner Asia.” Central Asian Survey 30, no. 3–4 (2011): 469–85.

Esman, J. Milton. Diasporas in the Contemporary World. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2009. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 325 ES M)

Fairley, J. Nancy. “Dreaming Ancestors in Eastern Carolina.” Journal of Black Studies 33, no. 5 (May 2003): 545–61. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Falzon, Mark-Anthony. “‘Bombay, Our Cultural Heart’: Rethinking the Relation Between Homeland and Diaspora.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 26, no. 4 (2003): 662–83.

Fontana, Bernard L. “What Is Ethnohistory?” Arizoniana 2, no. 1 (Spring 1961): 9–11. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Gadacz, Rene R. “The Language of Ethnohistory.” Anthropologica 24, no. 2 (1982): 147–65. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Geana, Gheorghita. “Remembering Ancestors: Commemorative Rituals and the Foundation of Historicity.” Journal History and Anthropology 16, no. 3 (September 2005): 349–61.

Hadi Sidomulyo and Nigel Bullough. Napak Tilas Perjalanan [Napak Tilas Travel]. Jakarta: Wedatama, 2007.

Hall, Daniel George Edward. A History of South-East Asia. London: Macmillan, 1960.

Harkin, Michael E. “Ethnohistory’s Ethnohistory: Creating a Discipline From the Ground Up.” Social Science History 34, no. 2 (Summer 2010): 113–28. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Hazra, Kanai Lal. Indonesia: Political History and Hindu and Buddhist Cultural Influences. New Delhi: Decent Books, 2007. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.8 HAZ)

Hening Wasisto. “Javanese Diaspora Event III Resmi Dibuka Siang Ini.” TribunJogja, 17 April 2017.

Hidayah Amin. Bahasa: A Guide to Malay Languages: Banjar, Bawean, Buginese, Javanese, Malay, Minangkabau, Slitar and Tagalog. Singapore: Helang Books, 2017. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 499.28 HID)

Huggan, Graham. “Post-Coloniality.” In Diaspora: Concepts, Intersections, Identities, edited by Kim Knott and Sean McLoughlin. England: Zed Books, 2010, 55–58.

Hussin Mutalib. Singapore Malays: Being Ethnic Minority and Muslim in a Global Citystate. New York: Routledge, 2012. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 305.8992805957 HUS)

I Ketut Riana. Kakawin Desa Warnnana Uthawi Nagara Krtagama: Masa Keemasan Majapahit. Jakarta: Penerbit Buku Kompas, 2009.

Ibrahim Tahir, ed. A Village Remembered Kampong Radin Mas 1800s–1973. Singapore: OPUS Editorial Private Limited, 2013. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 VIL-[HIS])

Iorio, Monica and Andrea Corsale. “Diaspora and Tourism: Transylvanian Saxons Visiting the Homeland.” Tourism Geographies 15, no. 2 (2013): 198–232.

“Javanese Diaspora Event III ‘Ngumpulke Balung Pisah’.” JogjaTV, 23 March 2017.

Khachig, Tololyan. “The Contemporary Discourse of Diaspora Studies.” Journal Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 27, no. 3 (December 2007): 647–59.

Kim Knott and Sean McLoughlin, eds. Diaspora: Concepts, Intersections, Identities. England: Zed Books, 2010.

Kuutma, Kristin. “Concepts and Contingencies in Heritage Politics.” In Anthropological Perspectives on Intangible Cultural Heritage, edited by Arizpe Lourdes and Cristina Amescua. London: Springer, 2013, 1–15.

Kwa, Chong Guan, Heng Derek Thiam Soon and Tan Tai Yong. Singapore, a 700-Year History: From Early Emporium to World City. Singapore: National Archives of Singapore, 2009. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.5703 KWA-[HIS])

Leong, Amelia M. W., et al. “Nostalgia As Travel Motivation and Its Impact on Tourists Loyalty.” Journal of Business Research 68, no. 1 (January 2015): 81–86.

Levitt, Peggy. “Transnationalism.” In Diaspora: Concepts, Intersections, Identities, edited by Kim Knott and Sean McLoughlin. England: Zed Books, 2010, 39–44.

Levi, Andreh, Andrey Levi and Alex Weingrod. Homelands and Diasporas: Holy Lands and Other Places. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2005.

Long, J. Nicholas. Being Malay in Indonesia: Histories, Hopes, and Citizenship in the Riau Archipelago. Singapore: Asian Studies Association of Australia in Association with NUS Press and NIAS Press, 2013. (From National Library Singapore, call no RSING 305.89928059814 LON)

Man, U-Lo. “Exploring the Motivation of Chinese Immigrants for Homeland Tourism.” Current Issues in Tourism 20, no. 5 (May 2014): 521–35.

Marschall, Sabine. “Travelling Down Memory Lane: Personal Memory as a Generator of Tourism.” Tourism Geographies 17, no. 1 (2015): 36–53.

–––. “Homesick Tourism: Memory, Identity and (Be)longing.” Current Issues in Tourism, 18, no. 9 (2015): 876–982.

Maruyama, Naho and Amanda Stronza. “Roots Tourism of Chinese Americans.” Ethnology 49, no. 1 (Winter 2010): 23–44. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Marwati Djoened Poesponegoro and Nugroho Notosusanto. Sejarah Nasional Indonesia, Jilid II. Yogyakarta: Balai Pustaka, 1992.

Miksic, John N. and Cheryl-Ann Low Mei Gek, eds. Early Singapore, 1300s–1819: Evidence in Maps, Text, and Artefacts. Singapore: Singapore History Museum, 2004. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.5703 EAR-[HIS])

Mitchell, Jon P. “The Nostalgic Construction of Community: Memory and Social Identity in Urban Malta.” Ethnos 63, no. 1 (1998): 81–101.

Mohamed Nahar Ros. Sacred Places: Keramats in Singapore. Singapore: National University of Singapore, 1984. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 305.89928095957 MOH)

Morawska, Ewa. “‘Diaspora’ Diasporas’ Representations of Their Homelands: Exploring the Polymorphs.” Ethnic and Racial Studies, 34, no. 6 (2011): 1029–048.

Muljana, Slamet. Nagara Kretagama: Tafsir Sejarah. Yogyakarta: LK is Group, 2011.

Munoz, Paul Michel. Early Kingdoms of the Indonesian Archipelago and the Malay Peninsula. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet, 2006. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.801 MUN)

Nederbragt, J. A. Handbook of the Netherlands and Overseas Territories. The Hague: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Nederland, Economic Section, 1931. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 949.2 HAN-[JK])

Niermeyer, J. F. De Oost En De West. Groningen: Wolters, 1909.

Noor Aisha Abdul Rahman and Azhar Ibrahim. Malays. Singapore: Institute of Policy Studies and Straits Times Press, 2017. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 305.89928095957 NOO)

Oonk, Gijsbert, ed. Global Indian Diasporas: Exploring Trajectories of Migration and Theory. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2007. (From National Library Singapore, call no. R 304.80954 GLO)

Pang, Eng Fong and Armoud De Meyer, eds. Within and Without: Singapore in the World, the World in Singapore. Singapore: Singapore Management University, 2016. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 WIT-[HIS])

Peachey, Anna and Mark Childs. Reinventing Ourselves: Contemporary Concepts of Identity in Virtual Worlds. London: Springer, 2011.

Pinho, Patricia de Santana. “African-American Roots Tourism in Brazil.” Latin American Perspectives 35, no. 3 (May 2008): 70–86. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Prapanca, Mpu. Desawarnana (Nagarakrtagama). Translated by Stuart Robson. Leiden: KITL V., 1995. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.8012 PRA)

Prastowo, Fuji Riang, et.al. “Babad Jawa Ing Paran “Bab Jawa Ing Landa”, Sejarah Orang Jawa Di Belanda.” [The chronicle of javanese diaspora in the Netherlands]. Yogyakarta: Dinas Kebudayaan D.I.Yogyakarta, 2017.

Prick van Wely, F. P. H. Indische Woorden En Hunne Equivalenten in De Moderne Talen. Batavia: G. Kolff & Co., 1903. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RUR 439.31 PRI)

Purwadi. Babad Majapahit. Yogyakarta: Media Abadi, 2005.

Ratnasingam, Malini. “National Identity: A Subset of Social Identity?” In Ethnic Relations and National Building: The Way Forward, edited by Maya Khemlani David, James McClellan, Yeok Meng Ngeow and Wendy Mei Tien Yee. Petaling Jaya: Strategic Information and Research Development Centre, 2010. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.5 ETH)

Ricklefs, M. C. A History of Modern Indonesia since c.1200. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2001. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.8 RIC)

Rouffaer, G. P. and R. O. Winstedt, “The Early History of Singapore, Johore & Malacca.” Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 86 (November 1922): 257–60. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Rozen, Minna. Homelands and Diasporas: Greeks, Jews and Their Migrations. London: I. B. Tauris, 2008. (From National Library Singapore, call no. R 909.04893 HOM)

Russell, Dale W. “Nostalgic Tourism.” Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 25, no. 2 (October 2008): 103–16.

Safran, William. “Comparing Diasporas: A Review Essay.” Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies 8, no. 3 (Winter 1999): 255–91.

Schneider, William and Aron Crowell. Living With Stories: Telling, Re-Telling, and Remembering. Logan: Utah State University Press, 2008.

Schraam, Katharina. African Homecoming: Pan-African Ideology and Contested Heritage. California: Left Coast Press, 2010.

Shashangka, Damar. Sabda Palon III: Geger Majapahit. Jakarta: Penerbit Dolphin, 2013.

Sheffer, Gabriel. “Homeland and Diaspora: An Analytical Perspective on Israeli–Jewish Diaspora.” Ethnopolitics 9, nos. 3–4 (2010): 379–99.

Singapore. Department of Statistics. Census of Population 2010. Statistical Release 1, Demographic Characteristics, Education, Language and Religion. Singapore: Department of Statistics, Ministry of Trade and Industry, 2011. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 304.6021095957 CEN)

Straits Times. Kao, Delphine. “On Show: Culture of Local Javanese Community.” 28 May 2016, 10. (From NewspaperSG)

Tan, Lesley-Anne and Monica Lim. Secrets of Singapore: National Museum. Singapore: Epigram Books, 2017. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 TAN)

Tham, Seong Chee. Defining “Malay”. Singapore: Department of Malay Studies, National University of Singapore, 1992. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 305.899205957 THA)

Turnbull, C. M. A History of Singapore 1819–1988. Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1989. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 TUR-[HIS])

Vertrekken. “van Soerabaia.” Soerabaiasch-Handelsblad 187 (15 August 1892): 4, accessed from delpher.nl.

Walree, Emile David Van. Economic Relations of the Netherlands Indies With Other Far Eastern Countries. Amsterdam: National Council for the Netherlands and the Netherlands Indies of the Institute of Pacific Relations, 1935. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 382.0959805 WAL)

Wood, W. Raymond. “Ethnohistory and Historical Method.” Archaeological Method and Theory 2 (1990): 81–109. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Yeo, Stephanie. Re)presenting Histories: Experiences and Perspectives From the National Museum of Singapore. Singapore: National Museum of Singapore, 2017. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 069.5095957 REP)

Zee, D. Van Der. Batavia De Koningin Van Het Oosten. Rotterdam: Schueler, 1925.

Zhao, Shanyang, Sherri Grasmuck and Jason Martin. “Identity Construction on Facebook: Digital Empowerment in Anchored Relationships.” Computers in Human Behavior 24, no. 5 (September 2008): 1816–836.

Anthropological Sources

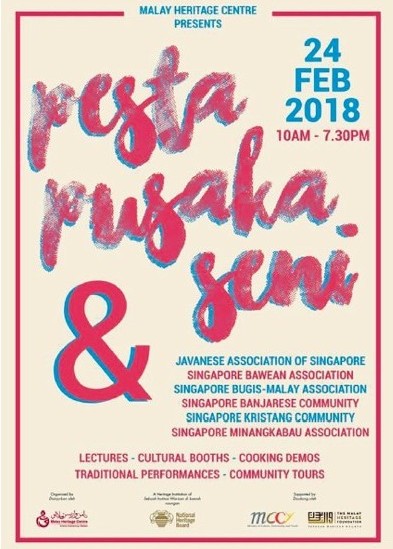

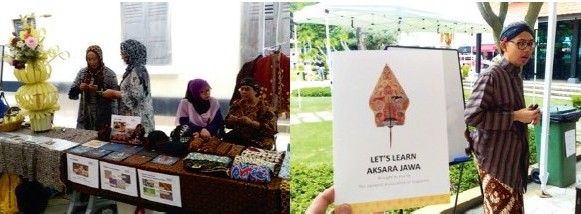

This ethnography was conducted through fieldwork by means of interviews and conversations from November 2017 to May 2018: Participation during a “Pesta Pusaka Seni” event held by the Malay Heritage Centre on 24 February 2018; in-depth interviews/FG D with Suryakencana Omar and Zuraidah Ehsan in Paya Lebar on 18 January 2018; visiting Sujono’s flat for in-depth interviews on 25 February 2018, 21 April 2018 and 19 May 2018.

Suryakencana Omar

The Head of Javanese Association of Singapore (JAS ); Conversations on Facebook since 2015, in-depth interview in Paya Lebar on 18 January 2018, conversations at the Malay Heritage Centre on 24 February 2018.

Zuraidah Ehsan

Member of JAS ; In-depth interview in Paya Lebar on 18 January 2018, conversations at the Malay Heritage Centre on 24 February 2018.

Sujono

A retiree; The second descendant of the first Javanese migrant in the 1920s; In-depth interview held in Jurong East on 25 February 2018 and 21 April 2018.

Sri Sulistiyanti Sujono

A Facebook group administrator of SambungRoso Java Suriname-Indonesia; Conversations on Facebook since 2016 and Instagram since 2018, conversations at Orchard (Singapore) on 15 January 2018, in-depth interviews in Jurong East on 25 February 2018 and 21 April 2018.

Fistri Abdul Rahim

A member of JAS; Conversations on Facebook since 2015 and Instagram since 2017, conversations at the National Library, Singapore on 25 November 2017 and at the Malay Heritage Centre on 24 February 2018.

Haider Surya Sahle

A Facebook group administrator of Javanese Singaporeans; Conversations on Facebook since 2016 and at the Malay Heritage Centre on 24 February 2018.

Hafiz Rashid

A Boyanese who speaks Javanese and loves its heritage, as well as a JAS member; Conversations at the National Library, Singapore on 25 November 2017 and at the Malay Heritage Centre on 24 February 2018, in-depth discussions at the National Library, Singapore on 12 February 2018 and 19 February 2018.

Mimie Sulamie

A member of JAS ; Conversations at the Malay Heritage Centre on 24 February 2018.

Hidayat Amat

A member of JAS ; Conversations on Facebook since 2016 and Instagram since 2017, conversations at the Malay Heritage Centre on 24 February 2018.

Abd Azim Ahmad

A merchant; Conversations at Arab Street/Kampong Java in Kampong Glam on 20 January 2018.

Afizul Hakem

A food-seller; Conversations at Arab Street/Kampong Java in Kampong Glam on 20 January 2018.

Muh.Musaddiq

A merchant; Hostel worker; Conversations at Arab Street/Kampong Java in Kampong Glam on 20 January 2018.

NOTES

-

Jewellery typical of the Majapahit empire were unearthed by archaeologists in the late 20th century in Bukit Larangan (present-day of Fort Canning in Singapore). This points to the presence of the Javanese in Singapore since the 14th century. During the excavations from 1926 to 1928 near the Keramat Iskandar Shah in Bukit Larangan, workers unearthed gold ornaments such as a pair of earrings and an armlet that was engraved with the Majapahit demoniac Kala face, an epithet of Siva (Kwa Chong Guan, Heng Derek Thiam Soon and Tan Tai Yong, Singapore, a 700-Year History: From Early Emporium to World City) (Singapore: National Archives of Singapore, 2009), 14 (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.5703 KWA-[HIS]); John N. Miskic and Cheryl-Ann Low Mei Gek, eds., Early Singapore, 1300s–1819: Evidence in Maps, Text, and Artefacts (Singapore: Singapore History Museum, 2004, 17 (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.5703 EAR-[HIS]). Some experts believe these artefacts show that Javanese royalty had lived in this area (Lesley-Ann Tan and Monica Lim, Secrets of Singapore: National Museum (Singapore: Epigram Books, 2017), 4. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 TAN)). The bathing princesses and the ruins wall, nearly 5m wide and 3m high, was discovered in 1822 by John Crawfurd. This wall was included in Chinese merchant Wang Da Yuan’s chronicle in 1349. Wang noted that prior to his visit to Singapore in 1330, the Siamese had invaded the city. The locals had withstood the attack from behind a wall, much like a fortress. The 14th century saw the Javanese-Majapahit and Siamese Ayutthaya kingdoms interminably battling for hegemony in the region called Tumasik (Melissa Diagana and Jyoti Angresh, Fort Canning Hill: Exploring Singapore’s Heritage and Nature (Singapore: ORO editions, 2013) 33. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 DIA-[HIS])) ↩

-

Nagarakrtagama, also known as Desawarnana, is an old Javanese eulogy to the Majapahit King Rajasanagara (known informally as Hayam Wuruk) written by the Superintendent of Buddhist Affairs (Dharmadhyaksa Kasogatan), whose pen-name was Mpu Prapanca, in 1365 during the reign of Hayam Wuruk (1330-1367). Hayam Wuruk had wanted to conquer all of Nusantara under the Majapahit kingdom (Hadi Sidomulyo and Nigel Bullough, Napak Tilas Perjalanan [Napak Tilas Travel] (Jakarta: Wedatama, 2007, 3) ↩

-

The verse of Nagarakrtagama in Kawi that identifies Tumasik as part of the Javanese-Majapahit kingdom (I Ketut Riana, Kakawin Desa Warnnana Uthawi Nagara Krtagama: Masa Keemasan Majapahit (Jakarta: Penerbit Buku Kompas, 2009, 99), can be translated as follows: “In the territory of Pahang, the main places are Hujung and Medini, Lengkasuka and Sai as well as Kelanten and Tringgano, Nasor, Paka, Muwar, Dungun, Tumasik as Sang Hyang Hujung, Kelang, Keda, Jere, Kanjap, and Niran, the whole region as a group”. ↩

-

This oath pledge was written in Pararaton, the book of Kings of Singhasari and Majapahit, in the late 15th century, as follows:

“Sira Gajah Madapatih Amangkubhumi tan ayun amuktia palapa, sira Gajah Mada:

“Lamun huwus kalah nusantara isun amukti palapa, lamun kalah ring Gurun, ring Seran,

Tañjung Pura, ring Haru, ring Pahang, Dompo, ring Bali, Sunda, Palembang, Tumasik,

samana isun amukti palapa.”

(He, Gajah Mada Patih Amangkubumi, does not wish to cease his fasting. Gajah Mada:

“If [I succeed] in defeating (conquering) Nusantara, [then] I will break my fast. If Gurun,

Seram, Tanjung Pura, Haru, Pahang, Dompo, Bali, Sunda, Palembang, Temasek/Tumasik,

are all defeated, [then] I will break my fast.”). (Agung Kriswanto, Pararaton (Jakarta: Wedatama Widya Sastra, 2009), 106 (From National Library Singapore, call no. Malay RSEA 899.2221 PRA); Purwadi, Babad Majapahit (Yogyakarta: Media Abadi, 2005), 25. ↩ -

In Java, Demak was declared as the first Islamic Sultanate after Daha, the capital city of Majapahit under the kingship of Girindrawardhana, was conquered in 1517 (Marwati Djoened Poesponegoro and Nugroho Notosusanto, Sejarah Nasional Indonesia, Jilid II (Yogyakarta: Balai Pustaka, 1992, 325); Purwadi, Babad Majapahit, 45). In 1511 and 1521, a Javanese expedition to Singapore took place under Pati Unus, the second Sultan of Demak, who accepted the Sultan of Malacca’s request to seize Malacca from Portuguese control. This event was recorded in Suma Oriental by Tome Pires as the expedition of “Pate Onus”. However, the attempt to seize Malacca failed and Pati Unus was later known as Pangeran Sabrang Lor, literally translated as the “prince who crossed the sea to the north, the Malay Peninsula” (Anshory, H. M. Nasruddin and Arbaningsih, Negara Maritim Nusantara: Jejak Sejarah Yang Terhapus [Archipelago Maritime Countries: Erasing Traces of History] (Yogyakarta: Tiara Wacana, 2008), 73. ↩

-

It should be noted that on 6 February 1819, Sir Stamford Raffles, Sultan Hussein Shah of Johor and Temenggong Abdul Rahman signed a treaty that permitted the British to set up a trading post on a stretch of land in the southern area of Singapore. In August 1824, a second treaty was signed by Sultan Hussein, the Temenggong and Crawfurd, which allowed the British to control the whole island for the purpose of a port that did not charge taxes (Tan and Lim, Secrets of Singapore: National Museum, 24; Priscilla Chia and Trenton James Riggs, “We, the Citizens of Singapore,” in Within & Without: Singapore in the World; The World in Singapore, ed. Pang Eng Fong and Arnoud De Meyer (Singapore: Singapore Management University, 2016, 40. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 WIT-[HIS])). Due to the free trade policy, Singapore saw an influx of new arrivals from Nusantara comprising mainly the Javanese, Boyanese, Minangs, Baweanese, Bugis and Banjarese, who settled in Singapore in pursuit of better lives (Emile Walree and David Va, Economic Relations of the Netherlands Indies With Other Far Eastern Countries (Amsterdam: National Council for the Netherlands and the Netherlands Indies of the Institute of Pacific Relations, 1935), 6. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 382.0959805 WAL) ↩

-

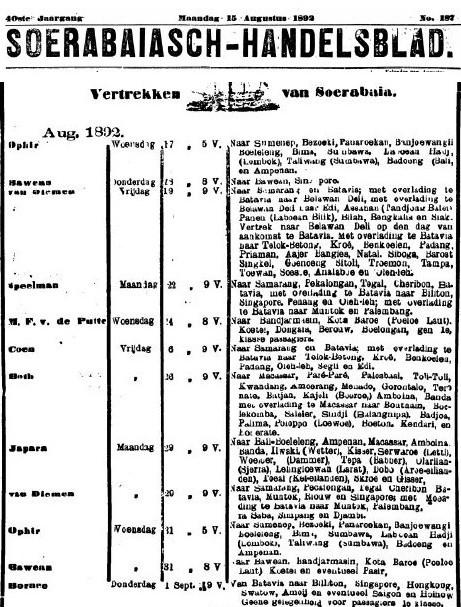

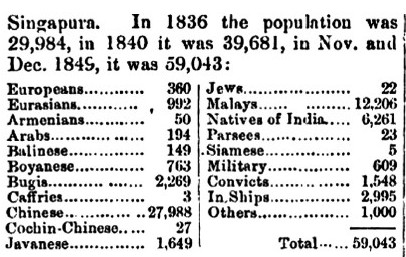

In the Ethnographic Survey of Singapore conducted by John Clammer in 1999, there were three main groups within the Malay community identified: Indigenous Malays (Orang Seletar, Orang Kallang and Orang Laut), people from the Malay Peninsula and Indonesians of other non-Malay ethnic groups. As described in 1825 census reports, there were 38 people of Javanese origins living in Singapore who mostly stayed in and around Kampong Glam, working as artisans, gardeners, religious teachers and merchants. There were notable Javanese entrepreneurs such as Haji Yusoff Haji Mohamed Noor, also known as Haji Yusoff “Tali Pinggang” (the belt merchant), Haji Hashim Haji Abdullah of Haji Hasjim Bookstore and Haji Ahmad Sonhadji, religious scholar and former principal of Madrasah Aljunied (Hidayah Amin), Bahasa: A Guide to Malay Languages: Banjar, Bawean, Buginese, Javanese, Malay, Minangkabau, Slitar and Tagalog (Singapore: Helang Books, 2017), 215–16. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 499.28 HID). In 1825, the Dutch colonial government in Java applied a levy on travel to Mecca for the Hadji, resulting in many Javanese travelling via Singapore instead. Hadji is the annual Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina (Prick van Wely, F. P. H., Indische Woorden En Hunne Equivalenten in De Moderne Talen (Batavia: G. Kolff & Co., 1903), 21. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RUR 439.31 PRI). Since the 1880s, upon their return from Hadji, many remained in Singapore as there were more job opportunities after western Johor became a business center. These job opportunities were supported by the Dutch East India company or Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC). As stated in Soerabaiasch-Handelsblad, a Dutch magazine published on 15 August 1892 shown on page 71, the British and Dutch had signed an agreement on a commercial ship route that would travel three times a month from Batavia or Surabaya to Singapore, namely the Speelman on 22 August 1892, Van Diemen on 29 August 1892 and Borneo on 1 September 1892 (J. A. Nederbragt, Handbook of the Netherlands and Overseas Territories (The Hague: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Nederland, Economic Section, 1931), 376. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 949.2 HAN-[JK]). In addition, there was to be a monthly mail service from Singapore via Java’s ports to Australia by the Streamers (D. Van Der Zee, Batavia De Koningin Van Het Oosten. Rotterdam: Schueler, 1925, 71). In 1922, around 281,000 people, 180,000 of whom were Indonesian, were exploited on the east coast of Sumatra (Deli), leading to thousands of Javanese fleeing to the neighbouring area belonging to British-controlled Malaysia and Singapore (John W. Brown, World Migration and Labour (Amsterdam: Bureau Centrale Informatie van Het Emigratiebestuur, 1926), 98–99; J. F. Niermeyer, De Oost En De West. Groningen: Wolters, 1909, 50). Since then, the total population of Singapore almost doubled from 29,984 in 1836 to 59,043 in 1849; of which comprised 1,649 Javanese (Edward Balfour, ed., Cyclopædia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia, Commercial, Industrial and Scientific (Madras: Printed at the Scottish & Adelphi presses, 1873), 398). (From National Library Singapore, call no. SBG 954 CYC)). By 1891, the number of Javanese had increased to 8,541 in Singapore. During the Japanese Occupation of Indonesia, a thousand Javanese laborers were sent to Singapore prior to being hired for the railroad projects in Thailand (Hidayah Amin, Bahasa: A Guide to Malay Languages, 216) ↩

-

As stated by Rahim (2006:522), there are some areas related to the 19th-century Javanese community living in Singapore, namely Kampong Java (around Arab Street), Kampong Tempei (near today’s Coronation Road), Kampong Chantek (near Binjai Park), Kampong Pachitan (near Kembangan) and various other settlements along Bukit Timah Road. There was a community theater established in the 1840s called Pondok Jawa, located near the Istana Kampong Gelam, which was a cultural venue for Javanese performances such as wayang kulit (shadow puppet theatre), wayang wong (masked drama) and ketoprak (Javanese opera). There was also a Javanese keramat (sacred place) in Singapore, namely the grave of Radin Mas Ayu in Telok Blangah, or in Kampong Radin Mas to be exact. Unfortunately, the kampong was demolished in 1973 to make way for development (Jeanette Chia Hwee Hwee, A History of the Javanese and Boyanese in Singapore (Singapore: NUS, 1992), 37 (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 305.89928095957 CHI); Ibrahim Tahir, ed. A Village Remembered Kampong Radin Mas 1800s–1973 (Singapore: OPUS Editorial Private Limited, 2013, 12. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 VIL-[HIS])). Myth has it that Radin Mas Ayu was a Javanese princess who had suffered greatly during her life (Mohamed Nahar Ros, Sacred Places: Keramats in Singapore (Singapore: National University of Singapore, 1984), 59. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 305.89928095957 MOH) ↩

-

The origin of the term “Melayu” is still clouded in uncertainty. The earliest mention of “Melayu” is in reference to a kingdom in Jambi, Sumatra, as written in Chinese records in 644 CE, which recounts that an emissary from the “Mo-Lo-Yu” of the Jambi or Batang Hari River in Sumatra visited the Chinese Imperial Court (Hussin Mutalib, Singapore Malays: Being Ethnic Minority and Muslim in a Global Citystate (New York: Routledge, 2012), 19 (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 305.8992805957 HUS); Tham Seong Chee, Defining “Malay” (Singapore: Department of Malay Studies, National University of Singapore, 1992), 1. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 305.899205957 THA)). As the Malay language is the lingua franca in the Nusantara archipelago, it provides a generalised identity for anyone from Nusantara as being Malay. However, for a long time, the term Malay was never used as a term for ethnic identity until European travellers began to categorise the indigenous people living in Nusantara as Malay. Besides the Malay language, the Melaka Sultanate in the 15th century played a key role in shaping the modern Malay identity through the practice of language (Malay), religion (Islam) and customary traditions (adat Melayu). Thus, a Malay is one who professes to being Muslim, speaks the Malay language and adheres to Malay customs (Nicholas J. Long, Being Malay in Indonesia: Histories, Hopes, and Citizenship in the Riau Archipelago (Singapore: Asian Studies Association of Australia in Association with NUS Press and NIAS Press, 2013), 34. (From National Library Singapore, call no RSING 305.89928059814 LON) ↩

-

This Facebook group facilitates interactions among the Javanese diaspora on social media, from places such as Suriname, the Netherlands and Malaysia, to Singapore, New Caledonia and Australia. One concrete manifestation of the roots journey was when the Javanese diaspora from across the world were reunited under the spirit of Ngumpulke Balung Pisah. Facebook plays an important role in bringing together disparate diasporic connections in the virtual realm. Therefore, the success of Ngumpulke Balung Pisah (held in 2015), was repeated from 17 to 23 April 2017 in collaboration with the Royal Palace of Yogyakarta, which saw the participation of hundreds from the Javanese diaspora (“Javanese Diaspora Event III ‘Ngumpulke Balung Pisah’.” JogjaTV, 23 March 2017) ↩