Chinese Newspaper Literary Supplements In Singapore's Postwar Literary Scene

By Seah Cheng Ta

Introduction

Amid the booming newspaper industry and active Chinese literary scene in Singapore after the Second World War, two editors of newspaper literary supplements stood out for their contributions: Xing Ying (杏影; 1911–67) and Yao Zi (姚紫; 1920–82). The supplements under their editorship were influential and informed local literary trends in the 1950s and 1960s. Newspaper supplements played a significant role in promoting literature and literary aesthetics and developing local literary talent, because they were published more frequently than literary magazines and had a wider audience.1 They typically appeared as a half-page section near the end of the newspaper. For budding writers, these supplements served as a springboard to the more prestigious literary magazines.2

This paper discusses the editorial styles of Xing Ying and Yao Zi and their contributions to the literary scene in Singapore, such as the multicultural elements they introduced to the supplements, and their nurturing of young writers. The first section describes the postwar Chinese literary scene and the two editors’ backgrounds. Section two focuses on Yao Zi’s early newspaper supplement, Lü Zhou (绿洲, Oasis, November 1952– January 1953), and Xing Ying’s Wen Feng (文风, Literary Trends, January 1954–August 1958), analysing their differing editorial styles and literary approaches. The third section compares their mature literary supplements: Yao Zi’s Shi Ji Lu (世纪路, Century Road, October 1953–January 1954) and Xing Ying’s Qing Nian Wen Yi (青年文艺, Youth Literature and Arts, July 1960–February 1967). The last section focuses on the literary supplements, Zhou Mo Qing Nian (周末青年, Weekend Youth, November 1952–December 1952) in Lü Zhou, and Xin Miao (新苗, New Sprouts, March–August 1958) in Wen Feng. This section will also elaborate on the creation of new platforms for amateur writers and compare the editors’ responses to young readers.

The Postwar Singapore Chinese Literary Scene, 1945–60

In the early postwar period from 1945 to 1948 – known as the initial period of peace or recovery (和平初期/光复初期) – the Singapore Chinese literary scene flourished.3 Newspapers such as Sin Chew Jit Poh (星洲日报), Nanyang Siang Pau (南洋商报) and Min Pao (民报), as well as literary supplements like Chen Xing (晨星) and Feng Xia (风下), were revived. Literary organisations and drama groups resumed their publications and performances, adding to the vibrant arts scene.

A turning point came in 1948. In a bid to fight the communists in Malaya, the British colonial government declared a state of emergency. Newspapers such as Min Sheng Pau (民生报) and Nan Chiao Jit Pao (南侨 日报) closed down, many books from China were banned, and publications in Malaya and Singapore were censored. The number of newspapers and publications in Singapore dropped by about 14 percent, from 140 between 1945 and 1948, to 121 between 1949 and 1954. The control of literature and the arts led to a paucity of reading materials4 and the dampening of the literary scene.

At the same time, this sociopolitical environment gave rise to a cultural phenomenon known as “yellow culture” (黄色文化). Yellow culture refers to activities and behaviour perceived as degenerate, such as dance clubs, gambling and pornography.5 In October 1953, in what was seen as a tragic consequence of yellow culture, a 16-year-old girl was raped and killed at Pearl’s Hill. A public outcry ensued. Cultural institutions, student organisations and schools organised anti-yellow culture campaigns, and students from Chinese schools such as Chung Cheng High School and The Chinese High School initiated the slogan, “Resist yellow culture” (抵制黄色文化). The anti-yellow culture movement (反黄运动) received widespread public support.

The movement was another turning point in the development of Chinese literature and newspapers in Singapore. New compositions such as songs, dramas, novels and poems emerged, many of which stressed the importance of a healthy mind,6 in opposition to the corrupting influence of yellow culture. The number of literary works increased by 25 percent, from 113 before the anti-yellow culture campaign, to 142 in 1955.7 In the same year, there were 414 Chinese newspapers and publications, more than twice compared to 163 in the prewar period from 1837 to 1941.8

The vibrant Chinese literary and newspaper scene in the 1950s can be attributed to three reasons. First, the British colonial government relaxed its regulations on publications. Except for those championing extreme anti-government views, all other publications could be registered with licences. This led to a resurgence of publishing activity, including materials with “yellow” elements. Second, the increased rigour in Chinese education in the 1950s led to a larger readership for Chinese newspapers, which were more affordable for the masses. Third, the import ban on publications from China and Taiwan meant a scarcity of reading materials for Singapore’s Chinese intellectuals, who thus turned to local Chinese newspapers.9

The 1950s also saw local Chinese beginning to reassess their affiliation with Singapore vis-à-vis China. In 1955, the People’s Republic of China announced that overseas Chinese would not be allowed to hold dual nationalities. Local newspapers reflected the shifting sentiments of the day, with interest clearly moving from China affairs to local developments.10 Articles on issues in China accounted for 69.7 percent of news coverage in 1946, but declined to 22.5 percent by 1950, while articles related to Singapore and Malaya rose from 19 percent in 1946 to 84.3 percent in 1959.11 During this period, the newspaper literary supplements edited by Yao Zi and Xing Ying began to publish discussions on local issues and feature multicultural elements.

Xing Ying and Yao Zi

Xing Ying was the pen name of Yang Shou Mo (杨守默; birth name Yang Fang Jie 杨芳洁). Born in Sichuan province, China, in 1911, he was exposed to several different cultures in his youth. He received his secondary education in Japan and studied English literature at Waseda University in Tokyo. At 30, he was employed by the Allied Forces headquarters in India, on account of his fluent Japanese, and wrote articles published in the Calcutta China Times.12 After the war, he moved to Singapore in 1946, working as a translator at Nanyang Siang Pau and as a teacher at The Chinese High School. Prior to joining Nanyang Siang Pau, Xing Ying had little experience in editing and translation, and had rejected an offer to be the editor of the literary supplement, Lü Zhou. He eventually took over editorship of Wen Feng, the literary supplement of Nanyang Siang Pau, in 1954. Not only was he successful in his journalism career, Xing Ying was a good prose writer and wrote books such as While You Are Young (趁年轻的 时候, 1958), Books and People (书与人, 1960) and Century of the Fools (愚人的 世纪, 1960), etc. He also contributed regularly to the literary supplements, Lü Zhou and Shi Ji Lu, both edited by Yao Zi. Xing Ying passed away in 1967 from illness at Singapore General Hospital at the age of 55.

Yao Zi, whose birth name was Zheng Meng Zhou (郑梦周), was born in Fujian province, China. As a student, he edited a small newspaper, Jiang Tao (江涛). He subsequently became an editor at Jiang Sheng Daily (江声日报) in China, before coming to Singapore in 1947, where he taught at Tao Nan School and Jin Jiang School. In 1949, his debut novel, Miss Hideko (秀子姑 娘), sold 16,000 copies in a single month; his subsequent novels in the 1950s and 1960s, such as The Lure of Coffee (咖啡的诱惑) and Storm (风波), were also popular. Yao Zi wrote under at least six different pen names in Shi Ji Lu. He was an editor at Nanfang Evening Post (南方晚报) from 1952 to 1953, Nanyang Siang Pau from 1953 to 1954, and Shin Min Daily News (新明日报) from 1969 to 1977. Yao Zi passed away in 1982, at age 62.

International Literature and Communication between Editors and Readers: Lü Zhou and Wen Feng

Lü Zhou and Wen Feng, edited by Yao Zi and Xing Ying respectively, are considered the two early literary supplements of the 1950s. The two men had different editorial philosophies. Yao Zi’s focus on literary aesthetics likely stemmed from his literary values as a novelist, and under his editorship, Lü Zhou published both international and local literature. Xing Ying focused on developing young writers, and with Wen Feng, he created a vibrant supplement that allowed greater interaction between readers and the editor. In Lü Zhou and Wen Feng, Yao Zi and Xing Ying honed their respective editorial styles, which became amplified in their later supplements.

Lü Zhou: Bringing Literary Aesthetics into the Nanyang Literary Scene

Yao Zi was the editor of the literary supplement Lü Zhou in Nanfang Evening Post from 15 November 1952 to 3 January 1953, editing a total of 33 issues. Lü Zhou published news on regional literature and introduced local writers, including Xing Ying and Wei Bei Hua (威北华), both of whom later became renowned writers and editors. Lü Zhou was Yao Zi’s first edited local literary supplement. In his first editorial in 1952, he wrote with palpable optimism that “hope brings light and joy to life”, and “one can hope for a better tomorrow”.13

Yao Zi was responsible for publishing a variety of genres in a single issue. For example, the 9 December 1952 issue of Lü Zhou (Figure 1) contains (1) a short story by himself, (2) a serial novel by local writer Yu Sha (余莎), (3) a translated review of works by the Russian writer Ivan Turgenev, (4) a regular column featuring Indonesian poems in translation, (5) a poem by Wei Bei Hua, (6) an essay by Li Qi (里奇) (one of Xing Ying’s pen names), and (7) international literary news.14

Lü Zhou usually relied on a few good writers for regular contributions. One of these regulars was Wang Ge (王葛),15 a talented Malayan known for his novels and essays. Lü Zhou published his novels16 such as Mimosa (含羞草), Sail (帆) and* Fog* (雾), his poem titled “Shell” (贝壳), and even his translation of the English naturalist Gilbert White’s 1789 essay on swallows.17 Several of the young regular contributors later became important writers. For instance, Zhao Xin (赵心), better known as Zhao Rong (赵戎), contributed many pieces of literary reviews and criticism, and Xing Ying’s essays and novels written under the pen name Li Qi appeared in almost every issue of Lü Zhou.18

Yao Zi broadened the horizons of local readers by introducing regional and international literature in Lü Zhou. A column was dedicated to poetry from Indonesia (Figure 2); featured works included “Vigil” (守夜), “A Lie” (欺瞒), “Last Night” (昨夜) and “Palace” (王宫).19 The poems were chosen and translated by Yue Zi Geng (越子耕), better known by his other pen names, Wei Bei Hua and Lu Bai Ye (鲁白野).20 Such columns introducing Indonesian and Malay literature to Chinese readers were quite a common sight in the newspaper literary supplements of the 1950s..21

Each issue contained translated Western literary works, such as the poem, “A Slave’s Dream” (一个奴隶的梦), by the American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and translated by Lin Qiu (林酋), and “The Petrified Forest” (大自然的反攻) by American playwright R. E. Sherwood and translated by Ai Li (艾骊)..22 The 26 November 1952 issue featured an excerpt of a short story by French writer Henry Bordeaux, and an article, “Centenary of Gogol’s Death” (果戈里百年祭) translated by He Lan (河兰)..23

Lü Zhou also introduced readers to contemporary writers from around Asia. In the issue of 19 November 1952, an article was published on the Korean writer Jang Hyeok-Ju and his new poem “Alas, Korea”..24 Works by Lü Lun (侣伦; 1911–88; birth name Li Lin 李霖), a famous novelist and screenwriter in Hong Kong, were featured prominently in the column, Honeyed Notes (蜜叶记语); they included pieces such as “The Sign of a Book Owner” (书主的标志), “Memory of the Moon” (月之忆) and “Black Tea” (红茶)..25

Yao Zi introduced a column, International Literary News (国际文坛消 息), edited by Di Jun (谛君). Rare for a Chinese newspaper supplement in the 1950s, this column exposed readers to developments in the worldwide literary scene. Articles covered a wide range of events and topics, such as “Belgium Issues Stamps Commemorating Writers” (比国发行作家纪念邮票), “Venice Establishes Literary Award among Nine Countries” (威尼斯创立 九国文学奖), “Children’s Literature in Argentina” (阿根廷的儿童文学) and “Puppets in Italy” (木偶人在意大利)..26 The column also featured articles on international writers and literary reviews, including “The Experience of a Reporter cum Writer: François Mauriac” (新闻记者兼作家的莫里亚 克略经历), written by Di Jun,.27 and a review, “Turgenev and His Works” (屠格涅夫及其作品), by the Irish writer Robert Lynd and translated by Yuan Si (原思). That the review was published in full over three issues of Lü Zhou was telling of the significance Yao Zi placed on the Russian writer. “The works of Turgenev,” he wrote, “are among the greatest in modern world literature.”.28

Wen Feng: Xing Ying and His Communication Tool with Readers

Xing Ying was the editor of Wen Feng in Nanyang Siang Pau from 18 January 1954 to 15 August 1958, during which 828 issues of the supplement were published. In the first two years, Wen Feng was published daily; after 1956, its publication became less regular, partly because of its narrow thematic scope – almost half of the works revolved around the lives of rubber plantation workers, employer-employee relationships, and the difficulties of finding employment.29

Unlike Yao Zi, who focused on publishing highly aesthetic literary works, Xing Ying used Wen Feng to encourage literature-loving youths to write freely,30 in line with his belief that journalism was a meaningful profession because journalists “can effect change in society with a pen”.31 Wen Feng’s emphasis on youth writing marked a clear change from the direction of its predecessor, Shi Ji Lu, under Yao Zi’s editorship. Xing Ying welcomed all writers, accepted articles based on the strength of their content, and proscribed personal attacks. The contributors came from different backgrounds, bringing a diversity of perspectives to Wen Feng. Some were professional writers, teachers and civil servants, while others were factory workers, gardeners, students or unemployed amateur writers.

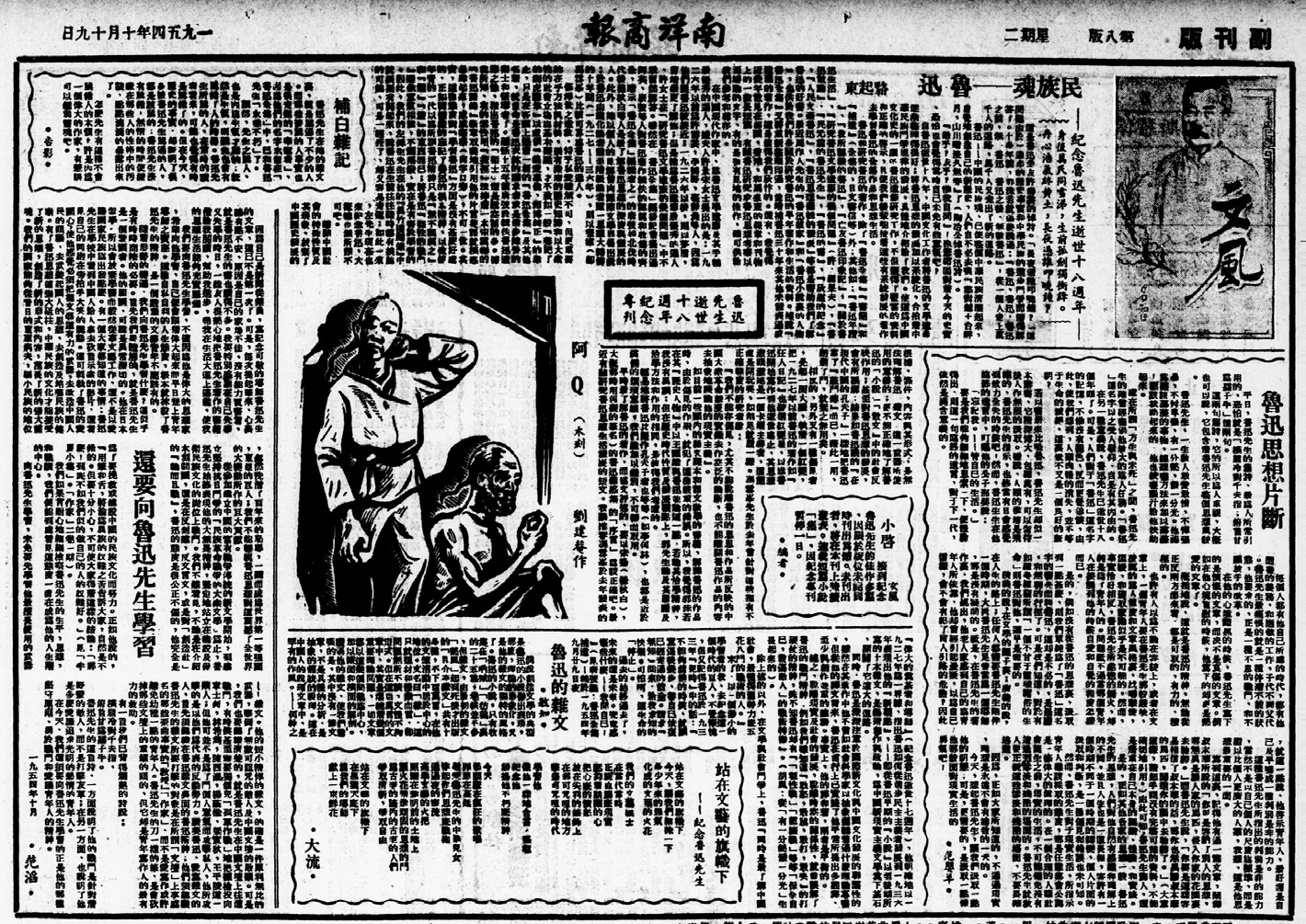

Like Lü Zhou, Wen Feng published works across a wide range of literary genres, including poems, novels, essays, literary reviews and social criticism, often accompanied by woodblock prints.32 Translated works were also frequently featured, such as the short story “The Selfish Giant” (自私的巨 人) by the Irish writer Oscar Wilde and translated by Wei Ding (惟丁).33 Under Xing Ying’s initiative, Wen Feng published special issues dedicated to individual writers. The 19 October 1954 special issue commemorating the Chinese writer Lu Xun (魯迅) featured poems and literary criticism on his works, and a woodblock print inspired by his novella, Ah Q. Lu Xun’s portrait was featured in Wen Feng’s title plate for that issue (Figure 3).34

Despite his lack of prior experience in editing a literary supplement, Xing Ying took care to develop writers and also became very popular with readers. Singaporean writer Lin Zhen (林臻) recalled that Xing Ying reviewed all contributions seriously and fairly – it did not matter if he knew the author personally, or if the author was not famous. He returned his edited articles to the writers with comments on how they could improve their work.35 Another Singapore Chinese writer, Xie Ke (谢克), who was also a prominent local editor in the 1970s and 1980s, recalled the lack of youth writing platforms in the 1950s: “Without Wen Feng and Xing Ying’s nurturing role, the Chinese literary scene in 1950s Singapore would have been less vibrant, and there would not have been so many youths interested in literature.”36

Xing Ying created an editorial column – Random Notes (补白杂记), later renamed Wen Feng Mailbox (文风信箱) – to express his views and communicate with the supplement’s readers, who responded well to it.37 One reader, Mian Ti (缅堤), wrote that this column was “a great inspiration” and his favourite thing to read in Wen Feng.38 Xing Ying also used this column to encourage young writers: “Please write about the issues in life, on matters that are down to earth, with less exaggeration. Write naturally and39 add your personal opinions. With that, you will become a better writer.”39

The editorial column also shows Xing Ying’s commitment to maintaining Wen Feng as a literary platform for writers of all stripes.40 When a reader, Peng Long Fei (彭龙飞), criticised the quality of the poems published in Wen Feng, Xing Ying replied: “Wen Feng does not have articles from professors, famous writers or scholars. Our writers are students from secondary and primary schools, or even workers or hawkers who are uneducated, so their works will not be impressive. That said, I do not see a major problem in the two lines you mentioned.”41 After a contributor was caught for plagiarism, Xing Ying asked readers to forgive the contributor, who had apologised: “I believe this unfortunate case of plagiarism will not tarnish the reputation of the literary supplement. Such a thing happened because of Wen Feng’s openness. We should give a second chance to those who admit their mistakes.”42 The column became an intimate space for him to share his thoughts with readers.

Professionalism and Cosmopolitanism: Shi Ji Lu and Qing Nian Wen Yi

The later supplements edited by Yao Zi and Xing Ying – Shi Ji Lu and Qing Nian Wen Yi, both in Nanyang Siang Pau – were more developed, as the editors were more experienced after editing Lü Zhou and Wen Feng. Like in Lü Zhou, Yao Zi focused more on literary aesthetics and relied on a small group of talented writers, while Xing Ying focused on nurturing writers, accepting many contributions from amateurs.

Shi Ji Lu: Maintaining Literary Aesthetics in a Literary Supplement

Yao Zi edited a total of 65 issues of Shi Ji Lu from its inception on 8 October 1953, to its end on 16 January 1954.43 In that short span, Shi Ji Lu became one of the most influential literary supplements in Singapore, with many contributors becoming well-known writers and editors, for instance Xing Ying, Zhao Rong, Wei Bei Hua, Xie Ke, Lian Shi Sheng (连士升), Miao Xiu (苗秀), Wei Yun (韦晕) and Liu Bei An (柳北岸), among others.

The first issue of Shi Ji Lu was published four days after the rape and murder of Zhuang Yu Zhen, the case that sparked the anti-yellow culture movement (Figure 4). Yao Zi was accused of being a yellow writer (黄色作家), for his novels such as Miss Hideko (秀子姑娘, 1949) and Ural Mountains (乌拉山之夜, 1950) contained descriptions of female body parts and sex scenes. Some of his poems published in Shi Ji Lu hint at the criticisms he faced. In “A Note to Myself at Age Thirty: A Reply to My Friends” (三十自题:兼答关怀我的朋友们), he wrote: “Worldly ups and downs are within my destiny, how can others judge my glory or downfall?”44

During this period, Yao Zi was supported by a group of writer friends. This further cemented his practice of relying on a small group of trusted writers for the supplement. Shi Ji Lu’s three regular contributors were Xing Ying, Zhao Rong and Miao Xiu, whose articles formed the supplement’s core, in addition to those by Yao Zi himself.45 Xing Ying wrote under two other pen names, Li Qi and Gongsun Zhe (公孙哲). Li Qi’s articles were about the writing life, such as “A Mature Writer” (成长了的作家) and “Notes Under the Light” (灯下笔记), while Gongsun Zhe wrote essays criticising unfairness in society, such as “Fear of Death and Others” (怕死及其他) and “Along the Road” (在马路旁边). Under the pen name Xing Ying, he wrote essays on Western literature, for instance “An Occasional Read of Mark Twain’s Novel” (偶读马克吐温的小说), and an essay on Western philosophy, “Live, Dead, Eternity (生· 死·永远).46 Zhao Rong wrote articles on literary history under the pen name Zhao Xin, such as “The Direction of Malayan Chinese Literature and Arts” (马华文艺底路向), and articles on morality under the pen name Bi Nu (笔奴), such as “Robbery and Morality” (盗与 道) and “To Reprimand the Liars” (斥文骗).47 The third regular contributor, Miao Xiu, wrote literature reviews such as “Lu Xun’s Former Residence and Zhou Zuoren” (鲁迅的故家与周作人) and “A Discussion on Literary Criticism” (谈文艺批评) under the pen name Shi Jin (史进).48 His novel Hanging Red (挂红) was written under the pen name Miao Yi (苗毅) and published over several issues of Shi Ji Lu.49 While Yao Zi’s reliance on a regular group of contributors supplied Shi Ji Lu with articles of literary merit, it resulted in less diversity of writing styles.

As a consequence of the anti-yellow culture movement, the atmosphere in the literary scene became more conservative. Yet, Yao Zi remained a creative and experimental editor. Under his editorship, Shi Ji Lu ushered in a new wave of Western literature to the postwar Nanyang literary scene. Compared to Lü Zhou, Shi Ji Lu featured more international content. The inaugural issue included two American short stories in translation – “The Cop and the Anthem” (警察和赞美诗) by O. Henry and translated by Jiang Nan Liu (江南柳), and “The Tax Collector” (给收税员) by J. P. McEvoy and translated by Zhu Ai (主艾) – and an essay on the American writer Jack London. Other works of Western literature subsequently published in Shi Ji Lu included “L’Aventure” (The Adventure, 艳遇) by the Norwegian writer Knut Hamsun, translated by Ya Ji (亞玑);50 “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” (睡谷的传说) by the American writer Washington Irving, translated by Jiang Nan Liu (江南柳);51 “A String of Blue Beads” (一串蓝珠) by the American writer Charles Fulton Oursler, translated by Xi Bang (希邦);52 and the poem “Out of the Night That Covers Me” (夜幕笼罩着我) by the British poet William Ernest Henley, translated by Shou Ming (受明).53 Shi Ji Lu occasionally also published translations of biographies of well-known writers, such as “The Life of O. Henry” (奥·亨利的生平), translated by Jia Sheng (加生).54

Yao Zi also published works by Hong Kong writers such as Lü Lun55 and Liu Yichang (刘以鬯). Liu contributed the short story “Enchanting Building” (迷楼),56 and under the pen name Linghu Ling (令狐玲), wrote reviews of Western literature, including “The Prejudices of Shakespeare” (莎士比亚的偏见) and “Roger de Coverley’s Style” (罗杰·考浮莱型).57 Yao Zi further broadened cultural discourse in Shi Ji Lu by publishing pieces on Indonesian music, which was rare for a literary supplement in the 1950s. Articles included “A Forgotten Indonesian Artist: The Composer of ‘Bengawan Solo’, Martohartono” (被遗忘的印尼艺术家: “梭罗河颂”的作者 玛尔多尼亚佐) by Mo Da (莫达), “The Attempt to Collect Indonesian Folk Songs” (搜集印尼民歌的尝试) by Sun Bin Lin (孙彬琳), and “My Views on Indonesian Music” (印尼音乐之我见) by Wei Zhi (微知).58

Shi Ji Lu also had a column for young writers called Youth Square (青年广场). The article “Eradicating the Perverts” (扫荡色情狂), written by Bai Xu (白絮), a student from Nanyang Girls’ High School, advocated the eradication of yellow culture in Singapore.59 Another contributor, Bin Bing (斌冰), discussed “The Future after Graduation” (毕业后的出路问题),60 while in “Preferential Treatment for Some Students” (优待学生), Huang Yi (黄裔) wrote that a movie company gave free tickets for American movies to students in English-medium schools, but not to students in Chinese schools. In contrast to Xing Ying, whose replies emphasised values and morals, Yao Zi replied sarcastically that Huang’s anger seemed misplaced: it suited English-school students to watch substandard American movies.61 Despite their different editorial philosophies, both editors promoted social justice for students in their own way.

Qing Nian Wen Yi: Nurturing Writers and Promoting Multiculturalism

In July 1960, Xing Ying became editor of Qing Nian Wen Yi in Nanyang Siang Pau, which became one of the longest-running literary supplements of the 1960s, when some newspapers supplements did not last even a month.62 It ran for 729 issues over nearly six and a half years, from 20 July 1960 to 6 February 1967.63 Qing Nian Wen Yi was the last literary supplement edited by Xing Ying, and with his death, the supplement ended too. The tagline in Qing Nian Wen Yi’s title plate (Figure 5) was a clear statement of its mission: “Published every Wednesday, a writing platform for the youth”.

Qing Nian Wen Yi published poems, essays and literature reviews by students. Compared to Xing Ying’s prior literary supplements, Wen Feng and Xin Miao, Qing Nian Wen Yi featured more articles on world literature; in this sense, it was more similar to Yao Zi’s Lü Zhou and Shi Ji Lu. Notable Western works appeared in translation, such as the essay “On National Prejudices” (爱国的偏见) by the Irish writer Oliver Goldsmith, and Mark Twain’s essay on writing technique, “How I Start Writing Essays” (我怎样开始写文章).64

This international perspective was partly due to Xing Ying’s love for foreign literature and exposure to Japan as a teenager. It can also be seen as a move to introduce world literature to young readers. Some of Xing Ying’s favourite foreign writers were Bernard Shaw, Anton Chekhov, Alexander Pushkin, Friedrich Schiller, William Somerset Maugham, Romain Rolland, Leo Tolstoy and Mark Twain. In 1960, Xing Ying was invited by Radio Singapore to give a series of 10 lectures on Japanese culture.65

Besides foreign literature, Qing Nian Wen Yi published writings related to international affairs. For instance, in the issue of 8 March 1961, the supplement ran a special column of student poems dedicated to Congo, in commemoration of the innocent lives lost during the ongoing Congo Crisis.66 Compared to Wen Feng, which focused on literary news, Qing Nian Wen Yi offered broader world news coverage.

Qing Nian Wen Yi also published translated articles on Malay literature, including M. Zain Salleh’s “The Mission of Literature during Nation Building” (建设时期的文学的任务), and an essay titled “An Outstanding Malay Poet: Tongkat Warrant” (东革·华兰: 杰出的马来诗人), introducing the poet who was better known by his pen name, Osman Awang.67 There were also original writings in Chinese on Malay literature, including an essay by Bi Cheng (碧澄), who praised Ishak Haji Muhammad for his persevering attitude towards writing (依萨哈芝穆哈末: 一位勤于写作的 马来作家).68 Such articles show that Chinese readers then were interested in Malay literature.

The Need for an Additional Supplement: Zhou Mo Qing Nian and Xin Miao

The literary supplements edited by Yao Zi and Xing Ying were so popular with readers and contributors that new literary supplements – Zhou Mo Qing Nian in Nanfang Evening Post, and Xin Miao with Qing Nian Wen Yi in Nanyang Siang Pau – were created to accommodate the increasing number of contributions from young writers. While both editors were concerned about the youth of Singapore, Yao Zi focused more on the social problems that students faced, while Xing Ying offered the students writing advice.

Zhou Mo Qing Nian and Youth Square

Yao Zi was the editor of the weekly literary supplement Zhou Mo Qing Nian, producing eight issues during his tenure from 1 November 1952 to 27 December 1952. He created Zhou Mo Qing Nian in response to aspiring young writers who could not get published in* Lü Zhou. In an editorial, Yao Zi wrote that the articles in *Zhou Mo Qing Nian might not be “up to standard”, but they focused more on content and less on writing technique.69

While Lü Zhou was more literary, Zhou Mo Qing Nian was targeted at the youth.70 The articles dealt with issues that concerned this demographic, such as education and social justice. Writings on observations about society included “Rubber Tappers” (割胶的工人) by Lin Jian (林建) and “Unemployment” (失业) by Yuan Yuan (媛媛).71 Other articles gave tips and encouragement to young writers who wanted to have their works published in newspapers, such as “How to Practise Writing” (怎样练习稿子) by Bu Dong Shi (不懂事),72 and “My Experience with Manuscript Rejection” (投稿 失败给我的经验) by Qin Kai (秦凯).73

As he would later do in Shi Ji Lu as well, Yao Zi created a column in Zhou Mo Qing Nian called Youth Square (青年广场), to allow students to give voice to injustices they suffered or observed (Figure 6). Yao Zi made it clear that the column was not a place to vent one’s personal anger; its purpose was to improve Chinese education in Malaya, by providing a forum for those treated unjustly to speak up, so that the school authorities could not turn a blind eye to abuses of power.74 In one case, a student had to put his studies on hold for a semester, but the school continued to charge tuition fees;75 in another case, a principal was called out for being partial in his selection of articles to be published in the school journal.76 The issues might seem immature and trivial, but they were serious matters for the supplement’s young readership. Hence, Zhou Mo Qing Nian was more than a literary supplement for the youth; it was a publication that concerned itself with youth welfare.

Besides Youth Square, Zhou Mo Qing Nian had another regular feature: a poetry column that showcased about five to seven poems by young writers in each issue. This demonstrates that Yao Zi was keen to encourage poetry writing among the youth, despite his overall emphasis on literary aesthetics. The poems tended to revolve around youthful aspirations and experiences, such as “Hope” (期待) by Xue Zi (学子), “If” (假使) by Wang Shao Quan (王绍全), “Awaking from a Dream” (梦醒) by Fa Yuan (发源), “Forced to Move” (迫迁) by Li Yin (李音), and “Laughter by the Seashore” (海滨的 笑声) by Xiao Ling (小绫).77

Xin Miao: Music Meets Literature

Xing Ying was the editor of Xin Miao, the “brother supplement” of Wen Feng. The publication of these two literary supplements in Nanyang Siang Pau overlapped by six months, from March to August 1958, which was also the lifespan of Xin Miao. Xin Miao did not have a fixed publication schedule – it was initially published thrice a week, but the frequency later dropped to once a week. Like Random Notes in Wen Feng, Xin Miao Mailbox served as a forum for readers and Xing Ying to communicate with one another.78

In creating Xin Miao, Xing Ying hoped to give secondary school students a platform to publish their writings. Ever the nurturer of writers, he wrote in his first editorial: “If you keep writing, the article gets better. If you keep using the pen, it gets sharper.”79 Singaporean writer Liu Shun (柳舜), who used to contribute to Xin Miao, recalled that Xing Ying was approachable and kind to younger writers, and listened to their concerns.80

Xin Miao published fiction, poems, essays, playscripts, illustrations and woodblock prints. Similar to Zhou Mo Qing Nian, the topics and themes were relevant to the lives of younger readers, with articles like “My First Overseas Trip” (我的第一次旅行) by Yang Zhi (杨之).81 The issue on 15 March 1958 (Figure 7), for example, included contributions such as “The First Test” (第一次测验), “Mango” (芒果), “Rabbit, Wolf, Elephant, Fox” (兔子·狼·大象·狐狸) and “In the Rubber Plantation” (在胶林里).82 Writings on local conditions were also popular, such as “Life in the Lower-income Class in Singapore and Malaya” (新马的一部分底层生活) by Xue Li Si (学裏思), “To the Wet Market” (上巴刹) by Xiao Yun (小韵), “My Village” (我的乡村) by Zhu Ying (竹影), “A Fire in Geylang” (芽笼的火灾) by Hong Xing (红星), and “Queenstown” (女皇镇), a poem by Gao Bang (高邦).83

Xin Miao was also a platform for music education and appreciation, with several of the issues featuring musical scores and music-related writing. Xin Miao published four scores, all composed by Huang Hun (黄昏), with lyrics by Hu Yang (湖洋): “Lullaby” (摇篮曲), “Midnight” (子夜), “A Nursery Rhyme My Mother Taught Me” (母亲教我一首儿歌) and “Idyllic Fields” (田园芳草) (Figure 7).84 Articles with musical themes included “Learning Music with Friends” (与友人学音乐) by Gao Xiu (高秀), “Music and Life” (音乐与人生) by Yu Si Yi (余思毅), and “My View on ‘Running Donkey’: Chinese Folk Dance” (我看《跑驴》:中国民间舞蹈) and “The New School Song” (新校舍歌) by Shan Ba Zi (山芭子).85

Conclusion

Both* Nanyang Siang Pau* and Nanfang Evening Post had significant readerships, which contributed to the influence of their literary supplements. As an editor, Yao Zi focused more on literary aesthetics, relying on a group of regular contributors, while Xing Ying focused more on developing writers and engaging readers. However, in Zhou Mo Qing Nian, Yao Zi, too, accepted amateur works from young writers.

Given their positions of influence, Yao Zi and Xing Ying played an important role in promoting local literature and writers, many of whom later became established figures in the Chinese literary scene. In addition, both editors brought world literature and new ideas to local readers, including Western writing techniques, translations of foreign classics, and international literary news. They also promoted multiculturalism by publishing translations of Malay literary works and original essays in Chinese discussing Malay literature. Vibrant, cross-cultural and multilingual, the literary scene in the 1950s and 1960s is an area that deserves further study.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Goh Yu Mei for helping me locate the research materials, Joanna Tan for her assistance in administrative matters during my fellowship at the National Library of Singapore, and the librarians – Kevin Seet, Juffri Supa’at, Ang Seow Leng, Lim Tin Seng and others – who helped me retrieve closed access materials and shared information with me. I would also like to thank Professor Chan Tah Wei for giving his comments and advice on the article, and Soh Gek Han and the editorial team for patiently editing my paper.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Cui, Guiqiang 崔贵强. Xinjiapo huawen baokan yu baoren 新加坡华文报刊与报人 [Singapore Chinese newspapers and journalists]. Singapore: Haitian wenhua qiye, 1993. (Call no. Chinese RSING 079.5957 CGQ)

Huang, Mengwen 黄孟文 and Xu Naixiang 徐乃翔, eds. Xinjiapo huawen wenxueshi chugao 新加坡华文文学史初稿 [First draft of the history of Chinese literature in Singapore]. Singapore: Department of Chinese Studies, National University of Singapore, 2002. (Call no. Chinese RSING C810.095957 XJP)

Liu, Binong 刘笔农, ed. Yao Zi yanjiu zhuanji 姚紫研究专集 [Yao Zi research collection]. Singapore: Singapore Literature Society, 1997. (Call no. Chinese RSING S895.185209 YZY).

Luo, Ming 骆明, ed. Xing Ying yanjiu zhuanji 杏影研究专集 [Xing Ying research collection]. Singapore: Singapore Literature Society, 1995. (Call no. Chinese RSING C810.092)

Peng, Weibu 彭伟步. Dongnanya huawen baozhi yanjiu 东南亚华文报纸研究 [A study of Chinese newspapers in Southeast Asia]. Beijing: Shehui kexue wenxian chubanshe, 2005. (Call no. Chinese RSEA 079.59 PWB)

Wang, Kangding 王慷鼎. Xinjiapo huawen baokan shi lunji 新加坡华文报刊史论集 [Collection of history of Chinese newspapers and periodicals in Singapore]. Singapore: Xinjiapo xin she 新加坡新社, 1987. (Call no. Chinese RSING 079.5957 WKD)

Wang, Lianmei 王连美_. Xing Ying: Ta buhui jimo_ 杏影: 他不会寂寞 [Xing Ying: He will not be lonely]. Singapore: National Library Board, 2009.

Yang, Songnian 杨松年. Xinma huawen xiandai wenxue shi chubian 新马华文现代文学史初编 [First compilation of the history of modern Chinese literature in Singapore and Malaysia]. Singapore: BPL jiaoyu chubanshe, 2000. (Call no. Chinese RSING C810.09YSN)

Newspaper articles

Bai Li Shan 白里山. “Wo kan ‘Pao Lü’: Zhongguo minjian wudao” 我看《跑驴》: 中国民间舞蹈 [My view on ‘Running Donkey’: Chinese folk dance]. Xin Miao 新苗, 24 May 1958, 15. (Microfilm NL2743)

Bai Xu 白絮. “Saodang seqingkuang” 扫荡色情狂 [Eradicating the perverts]. Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 17 November 1953, 9. (Microfilm NL2701)

Bi Cheng 碧澄. “Yisa Hazhi Muhamo: Yi wei qin yu xiezuo de Malai zuojia” 依萨哈芝穆哈末: 一位勤于写作的马来作家 [Ishak Haji Muhammad: A hardworking Malay writer]. Qing Nian Wen Yi 青年文艺, 25 December 1961, 18. (Microfilm NL3319)

Bin Bing 斌冰. “Biye hou de chulu wenti” 毕业后的出路问题 [The future after graduation]. Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 22 December 1953, 9. (Microfilm NL2701)

Di Jun 谛君. “Xinwen jizhe jian zuojia de Mo Li Ya Ke lue jingli” 新闻记者兼作家的莫里亚克略经历 [The experience of a reporter cum writer: François Mauriac]. LüZhou 绿洲, 18 December 1952, 3.

Gao Bang 高邦. “Nühuangzhen” 女皇镇 [Queenstown]. Xin Miao 新苗, 27 March 1958. (Microfilm NL2742)

Gao Xiu 高秀. “Yu youren xue yinyue” 与友人学音乐 [Learning music with friends]. Xin Miao 新苗, 10 June 1958, 17. (Microfilm NL2743)

—. “Deng xia biji” 灯下笔记 [Notes under the light]. Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 16 December 1953, 8. (Microfilm NL2701)

—. “Wentan zhengming” 文坛正名 [Rectification of the name of literary field]. LüZhou 绿洲, 1 December 1952, 3.

Li Ru 李儒. “Tingxue yi xueqi, ye yao jiao xuefei, zhi xu xiansheng ma, buzhun xuesheng ai” 停学一学期,也要交学费,只许先生骂,不准学生哀 [Lessons on hold for a semester, but school fees still charged: Teachers allowed to reprimand, students not allowed to cry foul]. Zhou Mo Qing Nian 周末青年, 6 December 1952, 3.

Linghu Ling 令狐玲. “Luo Jie Kao Fu Lai xing” 罗杰·考浮莱型 [Roger de Coverley’s style]. Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 23 November 1953, 9. (Microfilm NL2701)

—. “Sha Shi Bi Ya de pianjian” 莎士比亚的偏见 [The prejudices of Shakespeare]. Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 23 November 1953, 9. (Microfilm NL2701)

Liu, Yichang 刘以鬯. “Mi lou” 迷楼 [Enchanting building]. Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 17 October 1953, 5. (Microfilm NL2701)

Lü Lun 侣伦. “Hongcha” 红茶 [Black tea]. LüZhou 绿洲, 15 December 1952, 3.

—. “Shimian ye” 失眠夜 [Insomnia night]. _Shi Ji Lu_世纪路, 5 November 1953, 9. (Microfilm NL2701)

—. “Shu zhu de biaozhi” 书主的标志 [The sign of the book owner]. LüZhou 绿洲, 29 December 1952, 3.

—. “Yue zhi yi” 月之忆 [Memory of the moon]. LüZhou 绿洲, 12 November 1952, 3.

M. Zain Salleh. “Jianshe shiqi de wenxue de renwu” 建设时期的文学的任务 [The mission of literature during nation building]. Translated by Ma Li 马里. Qing Nian Wen Yi 青年文艺, 8 May 1961, 17. (Microfilm NL3319)

Miao Xiu 苗秀. “Gua hong” 挂红 [Hanging red]. Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 4 January 1954, 8. (Microfilm NL2702).

Miao Yi 苗毅. “Shenyuan de cheng” 深渊的城 [Abyss city]. Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 15 October 1953, 9. (Microfilm NL2701).

Mo Da 莫达. “Bei yiwang de Yinni yishujia: ‘Suoluo He song’ de zuozhe Ma Er Duo Ni Ya Zuo” 被遗忘的印尼艺术家: “梭罗河颂”的作者玛尔多尼亚佐 [A forgotten Indonesian artist: The composer of ‘Bengawan Solo’, Martohartono]. Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 10 December 1953, 8. (Microfilm NL2702)

Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报. “Shiliu sui nü xuesheng zai Zhenzhushan jiao canzao jian jie sha biming” 十六岁女学生在珍珠山脚惨遭奸劫杀毙命 [16-year-old female student tragically murdered after rape and robbery at foot of Pearl’s Hill]. 13 October 1953, 9. (Microfilm NL2700)

Oursler, Charles Fulton. “Yi chuan lan zhu” 一串蓝珠 [A string of blue beads]. Translated by Xi Bang 希邦. Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 6 November 1953, 9. (Microfilm NL 2701)

Qin Kai 秦凯. “Tougao shibai geiwo de jingyan” 投稿失败给我的经验 [My experience with manuscript rejection]. Zhou Mo Qing Nian 周末青年, 6 December 1952, 3.

Qing Nian Wen Yi 青年文艺. “Xian gei Gangguo” 献给刚果 [Dedicated to Congo]. 8 March 1961, 15. (Microfilm NL2766)

—. “Tingxue yi xueqi, ye yao jiao xuefei, zhi xu xiansheng ma, buzhun xuesheng ai” 停学一学期,也要交学费,只许先生骂,不准学生哀 [Lessons on hold for a semester, but school fees still charged: Teachers allowed to reprimand, students not allowed to cry foul]. 6 December 1952, 3.

—. “Tougao qi fengbo, xiaozhang you quan neng shigui, siwen jin saodi, bianzhe wuliang zuo bangxiong” 投稿起风波,校长有权能使鬼,斯文尽扫地,编者无良作帮凶 [Article submission stirs up a storm: Principal with power to manipulate, propriety a façade, editor as accomplice]. 27 December 1925, 3.

Zhu Ying 竹影. “Wo de xiangcun” 我的乡村 [My village]. Xin Miao 新苗, 11 March 1958, 18. (Microfilm NL2742)

NOTES

-

Peng Weibu 彭伟步, Dongnanya huawen baozhi yanjiu 东南亚华文报纸研究 [A study of Chinese newspapers in Southeast Asia] (Beijing: Shehui kexue wenxian chubanshe, 2005), 236. (Call no. Chinese RSEA 079.59 PWB) ↩

-

Xiang Yang 向阳, “Fukan xue de lilun jiangou jichu: Yi Taiwan baozhi fukan zhi fazhan guocheng ji qi shidai beijing wei changyu” 副刊学的理论建构基础:以台湾报纸副刊之发展过程及其时代背景为场域 [The fundamental construction of supplement studies: Field studies on the development of Taiwan newspaper supplements and its background era], Lianhe Wenxue, no. 96 (1992), 176–96. ↩

-

The terms “initial period of peace” (和平初期) and “initial period of recovery” (光复初期) are also used in Xinjiapo huawen wenxueshi chugao in discussions on the literary scene in the early postwar period_._ Huang Mengwen 黄孟文 and Xu Naixiang 徐乃翔, eds., Xinjiapo huawen wenxueshi chugao 新加坡华文文学史初稿 [First draft of the history of Chinese literature in Singapore] (Singapore: Department of Chinese Studies, National University of Singapore, 2002), 77. (Call no. Chinese RSING C810.095957 XJP) ↩

-

Wang Kangding 王慷鼎, Xinjiapo huawen baokan shi lunji 新加坡华文报刊史论集 [Collection of history of Chinese newspapers and periodicals in Singapore] (Singapore: Xinjiapo xin she 新加坡新社, 1987), 129–30. (Call no. Chinese RSING 079.5957 WKD) ↩

-

Huang and Xu, Xinjiapo huawen wenxueshi chugao, 84. The anti-yellow culture campaign does not equate to anti-pornographic materials. Chen Fan (陈凡) in his article, “General Discussion on the Anti-yellow Culture Movement” (泛论反对黄色文化运动) explains: “The yellow culture is not restricted to only pornography, excitements, tensions, sex… but to all actions that numb the feelings of people and poison them. Anything that prevents improvements and pull people away from their culture is yellow culture.” Chen Fan 陈凡, Men lei ji 闷雷集 [Muffled thunder] (Singapore: Qingnian shuju, 1959). (Call no. Chinese RCLOS C818 CF) ↩

-

“Shiliu sui nü xuesheng zai Zhenzhushan jiao canzao jian jie sha biming” 十六岁女学生在珍珠山脚惨遭奸劫杀毙命 [16-year-old female student tragically murdered after rape and robbery at foot of Pearl’s Hill], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 13 October 1953, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Yang Songnian 杨松年, Xinma huawen xiandai wenxue shi chubian 新马华文现代文学史初编 [First compilation of the history of modern Chinese literature in Singapore and Malaysia] (Singapore: BPL jiaoyu chubanshe, 2000), 249. (Call no. Chinese RSING C810.09YSN) ↩

-

Cui Guiqiang 崔贵强, Xinjiapo huawen baokan yu baoren 新加坡华文报刊与报人 [Singapore Chinese newspapers and journalists] (Singapore: Haitian wenhua qiye, 1993), 155. (Call no. Chinese RSING 079.5957 CGQ) ↩

-

Cui, Xinjiapo huawen baokan yu baoren, 177. ↩

-

Peng, Dongnanya huawen baozhi yanjiu, 242. ↩

-

Cui, Xinjiapo huawen baokan yu baoren, 161. ↩

-

Li Rulin 李汝琳, “Huiyi Yang Shou Mo” 回忆杨守默 [Remembering Yang Shou Mo], in Yao Zi yanjiu zhuanji 姚紫研究专集 [Yao Zi research collection], ed. Liu Binong 刘笔农 (Singapore: Singapore Literature Society, 1997), 10–14. (Call no. Chinese RSING S895.185209 YZY) ↩

-

“‘希望’能使生命发光,纵使沙漠上能够长出一根小草,开出一朵小花,我们也会感觉喜悦,愿意把更大的希望,寄托於明天…” Yao Zi 姚紫, “Jintian, mingtian” 今天 . 明天 [Today, tomorrow], LüZhou 绿洲, 15 November 1952, 3. ↩

-

Pen names were a common sight in Chinese newspaper literary supplements in the 1950s. Yao Zi wrote under several different names in LüZhou, for instance Yao Zi 姚紫, “Cheng tou zhanjiao qiufeng,” 城头战角秋风 [Top of the city wall, battle horn and the autumn wind], LüZhou 绿洲, 9 December 1952, 3; Huang Huai 黄槐, “Yesu xiafan” 耶稣下凡 [Jesus descends], LüZhou 绿洲, 贺斧, 13 December 1952, 3; He Fu 贺斧, “Shen” 神 [God], LüZhou 绿洲, 3 January 1953, 3, ↩

-

Wang Ge (1922–2011) was born Wang Jin Chang (王进昌). ↩

-

Novels were commonly published in the literary supplements in installments over several months. ↩

-

Wang Ge’s work in LüZhou included “Han xiu cao” 含羞草 [Mimosa] (26 December 1952), 32; “Beike” 贝壳 [Shell] (4 December 1952), 3; “Fan” 帆 [Sail], (8 December 1952), 3; “Wu” 雾 [Fog] (26 December 1952), 3 and Gilbert White, “Swallows,” trans. Wang Ge (24 December 1952), 3. ↩

-

Li Qi 里奇, “Wentan zhengming” 文坛正名 [Rectification of the name of literary field], LüZhou 绿洲, 1 December 1952, 3. ↩

-

Yue Zi Geng’s column, Introduction to Indonesia Poetry, in LüZhou included “Shouye” 守夜 [Vigil] by An Hua 安华 (November 1952, 3); “Qiman” 欺瞒 [A lie] by Shan Ni 珊尼 (24 November 1952, 3); “Zuoye” 昨夜 [Last night] by Shan Ni 珊尼 (5 December 1952, 3); and “Wanggong” 王宫 [Palace] by Mu Er Yue Nuo 母尔约诺 (9 December 1952, 3). ↩

-

Yue Zi Geng was born Li Xue Min (李学敏) in Ipoh and was a poet, a writer, an editor, a translator and an expert in the Malay language. He worked for both Chinese and Malay publications, such as Sin Chew Jit Poh and the Malay magazine, Majallah Bahasa Kebangsaan. Though the translator of the column is not explicitly identified, it is likely to be Yue. ↩

-

The column in LüZhou would probably have had greater impact if it had provided further poem analysis, an introduction to the poets, or more poems in each issue. ↩

-

Translated texts published in LüZhou included Henry W. Longfellow, “Yige nuli de meng” 一个奴隶的梦 [A slave’s dream], trans. Lin Qiu 林酋; R. E. Sherwood, “Daziran de fangong” 大自然的反攻 [The Petrified Forest], trans. Ai Li 艾骊; and “Napolun ceng xiang zuo zuojia” 拿破仑曾想做作家 [Napoleon once dreamed of being a writer], trans. Ai Li 艾骊, all published in LüZhou 绿洲, 4 December 1952. ↩

-

Henry Bordeaux, “_Sishengzi” 私生子 [Illegitimate child], trans. Situ Min 司徒敏, _LüZhou 绿洲, 26 November 1952, 3; He Lan 河兰, “Guogeli bainian ji” 果戈里百年祭 [Centenary of Gogol’s death], LüZhou 绿洲, 26 November 1952, 3. ↩

-

Sima Lu 司马卢, “Panghuang zai zhengzhi douzheng xia de Nanhan zuojia, Zhang He Zhou ji qi xinzhu: Wuhu Chaoxian” 彷徨在政治斗争下的南韩作家,张赫宙及其新著:呜呼朝鲜 [Hovering under the political struggle: South Korean writer Jang Hyeok-Ju and his new work, “Alas, Korea”], LüZhou 绿洲, 19 November 1952, 3. ↩

-

Lü Lun 侣伦, “Shu zhu de biaozhi” 书主的标志 [The sign of a book owner], LüZhou 绿洲, 29 December 1952, 3; “Yue zhi yi” 月之忆 [Memory of the moon], LüZhou 绿洲, 11 December 1952, 3; and “Hongcha” 红茶 [Black tea], LüZhou 绿洲, 15 December 1952, 3. ↩

-

The column on international literary news can be found in LüZhou 绿洲, 5 December 1952, 9 December 1952, and 22 December 1952 and a review, “Turgenev and His Works” (屠格涅夫及其作品), by the Irish writer Robert Lynd and translated by Yuan Si (原思). That the review was published in full over three issues of LüZhou was telling of the significance Yao Zi placed on the Russian writer. “The works of Turgenev,” he wrote, “are among the greatest in modern world literature.” ↩

-

Di Jun 谛君, “Xinwen jizhe jian zuojia de Mo Li Ya Ke lue jingli” 新闻记者兼作家的莫里亚克略经历 [The experience of a reporter cum writer: François Mauriac], LüZhou 绿洲, 18 December 1952, 3. ↩

-

“屠格涅夫的作品,的确是近代世界文学遗产中最伟大的一部分,但是,我们将如何接受这份文学遗产呢?… 因此,我们特约原思先生将它翻译过来,分三期在本刊登出。” LüZhou 绿洲, 8 December 1952, 3. ↩

-

Luo Ming 骆明, ed., Xing Ying yanjiu zhuanji 杏影研究专集 [Xing Ying research collection] (Singapore: Singapore Literature Society, 1995), 120. (Call no. Chinese RSING C810.092) ↩

-

“把这个园地作为鼓励爱好文艺的青年自由写作的地方。” Wen Feng 文风, 18 January 1954, 9. (Microfilm NL2702) ↩

-

Yang Shou Mo 杨守默, “Jizhe yu shehui: Jinian Nanyang Shangbao sanshi zhounian” 记者与社会: 纪念南洋商报三十周年 [Journalists and society: Commemorating Nanyang Siang Pau’s 30th anniversary], in Luo, Xing Ying yanjiu zhuanji, 114. ↩

-

Wen Feng 文风, 18 August 1954, 8. (Microfilm NL2702) ↩

-

Wen Feng 文风, 18 August 1954. ↩

-

Memories of Mr Lu Xun, Wen Feng 文风, 19 October 1954, 8. ↩

-

Lin Zhen 林臻, “Zhui yi diandi” 追忆点滴, in Luo, Xing Ying yanjiu zhuanji, 21. ↩

-

“如果少了《文风》,五〇年代新马的华文文艺不会那么昌盛;如果没有杏影先生的栽培,五〇年代不会涌现那么多的文艺青年。” Wang Lianmei 王连美, Xing Ying: Ta buhui jimo 杏影:他不会寂寞 [Xing Ying: He will not be lonely] (Singapore: National Library Board, 2009), 34 (Call no. Chinese C810.08 XIN). Xie Ke (谢克) was born in 1931, and his birth name was Seah Khok Chua. Besides being a writer, he was also an editor of Xin Sheng Dai (新声代) in Ming Pao 明报 (1966–70) and the newspaper literary supplements, Xue Fu Chun Qiu (学府春秋), Qing Nian Ban Lü(青年伴侣) and Xing Yun (星云)。 ↩

-

“Wen Feng Xin Xiang” 文风信箱 [Wen Feng Mailbox], Wen Feng 文风, 31 May 1954, 8 (Microfilm NL2706); Wen Feng 文风, 20 January 1954, 8. ↩

-

Mian Ti 缅堤, “Xiangqi Xing Ying xiansheng” 想起杏影先生 [Remembering Mr Xing Ying], in Luo, Xing Ying yanjiu zhuanji, 8. ↩

-

Ye Zhong Ling 叶钟玲, “Xing Ying yu Wen Feng fukan” 杏影与《文风》副刊 [Xing Ying and Wen Feng literary supplement], in Luo, Xing Ying yanjiu zhuanji, 118. ↩

-

“Wen Feng Xin Xiang” 文风信箱 [Wen Feng Mailbox], Wen Feng 文风, 7 July 1954, 8. (Microfilm NL2705) ↩

-

“Wen Feng Xin Xiang” 文风信箱 [Wen Feng Mailbox], Wen Feng 文风, 16 October 1954, 8. (Microfilm NL2706) ↩

-

Ye, “Xing Ying yu Wen Feng fukan,” 98. ↩

-

Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 8 October 1953, 9. (Microfilm NL2700) ↩

-

“世事升沉我自卜,君平怎得论荣枯? ” Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 7 December 1953, 9. (Microfilm NL2701) ↩

-

Yao Zi wrote many pieces under different pen names in Shi Ji Lu, including Tang Xi’s (唐兮) short story, “A Woman and a Man” (一个女的和一个男的); He Fu’s (贺斧) “How to Commemorate a Giant” (怎样纪念一个巨人), a tribute to Lu Xun; Fu Jian’s (符剑) short novel, Considerate (体贴); Shangguan Qiu’s (上官秋) “Pier” (码头); Ouyang Bi’s (欧阳碧) “Sorrows in the Night of Rain: Short Writings in the Night Window, Part 2 (雨夜的哀愁:夜窗短简之二); and Xiangyang Ge’s (向阳戈) “Walking Along the Century” (走在这个世纪). ↩

-

Li Qi 里奇, “Chengzhang le de zuojia” 成长了的作家 [A mature writer], Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 12 October 1953, 9; and “Deng xia biji” 灯下笔记 [Notes under the light], Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 16 December 1953, 8; Gongsun Zhe, “Pasi yu qita” 怕死及其他 [Fear of death and others], Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 20 October 1953, 9; and “Zai malu pangbian” 在马路旁边 [Along the road], Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 3 November 1953, 9; Xing Ying, “Oudu Ma Ke Tu Wen de xiaoshuo” 偶读马克吐温的小说 [An occasional read of Mark Twain’s novel], Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 22 December 1953, 8; and “Sheng, si, yongyuan” 生·死·永远 [Live, dead, eternity], Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 17 November 1953, 9. (Microfilm NL2701) ↩

-

Zhao Xin 赵心, “Mahua wenyi di zouxiang” 马华文艺底走向 [The direction of Malayan Chinese literature and arts], Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 18 November 1953, 9 (Microfilm NL 2701). “To Reprimand the Liars” was published in the last issue of Shi Ji Lu 世纪路; the article rebutted writers who feigned morality and labelled other writers as “yellow writers”. Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 16 January 1954, 8. ↩

-

An example of Miao Yi’s novel is “Shenyuan de cheng” 深渊的城 [Abyss city], Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 15 October 1953, 9. Shi Jin 史进, “Lu Xun de gujia yu Zhou Zuo Ren” 鲁迅的故家与周作人 [Lu Xun’s former residence and Zhou Zuo Ren], Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 5 December 1953, 8; and “Tan wenyi piping” 谈文艺批评 [A discussion on literary criticism], Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 16 December 1953, 8. (Microfilm NL2701) ↩

-

Miao Xiu 苗秀, “Gua hong” 挂红 [Hanging red], Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 4 January 1954, 8. (Microfilm NL2702) Yao Zi wrote an introduction to this story: “Gua Hong is a short novel. The author used the writing technique of literary realism and described a despicable person… This novel will be published in this supplement over a few issues.” Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 4 January 1954, 8. (Microfilm NL2702) Other novels were contributed by younger writers, such as Xie Ke (谢克), whose published pieces included “Lei Lei” 蕾蕾, Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 12 October 1953, 9; “Zai keshi li” 在教室里 [In the classroom], Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 19 November 1953, 9; “Fen” 坟 [Grave], Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 4 November 1953, 9; and “Linju men” 邻居们 [Neighbours], Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 7 January 1954, 8. ↩

-

Knut Hamsun, “Yanyu” 艳遇 [The adventure], trans. Ya Ji 亞玑, Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 3 October 1953, 9. (Microfilm NL2700) ↩

-

Washington Irving, “Shuigu de chuanshuo” 睡谷的传说 [The legend of Sleepy Hollow], trans. Jiang Nan Liu 江南柳, Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 16 October 1953, 9. (Microfilm NL2700) ↩

-

Charles Fulton Oursler, “Yi chuan lan zhu” 一串蓝珠 [A string of blue beads], trans. Xi Bang 希邦, Shi Ji Lu 世纪路_,_ 6 November 1953, 9. (Microfilm NL2701) ↩

-

William Ernest Henley, “Yemu longzhao zhe wo” 夜幕笼罩着我 [Out of the night that covers me], trans. Shou Ming 受明, Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 3 December 1953, 8. (Microfilm NL2701) ↩

-

“Ao Heng Li de shengping” 奥·亨利的生平 [The life of O. Henry], trans. Jia Sheng 加生, Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 14 January 1954, 8. ↩

-

Lü Lun 侣伦, “Shimian ye” 失眠夜 [Insomnia night], Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 5 November 1953, 9. (Microfilm NL2701) ↩

-

Liu Yichang 刘以鬯, “Mi lou” 迷楼 [Enchanting building], Shi Ji Lu 世纪路_,_ 17 October 1953, 5. (Microfilm NL2701) ↩

-

Linghu Ling 令狐玲, “Sha Shi Bi Ya de pianjian” 莎士比亚的偏见 [The prejudices of Shakespeare], Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 23 November 1953, 9; Linghu Ling 令狐玲, “Luo Jie Kao Fu Lai xing” 罗杰·考浮莱型 [Roger de Coverley’s style], Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 23 November 1953, 9. (Microfilm NL2701) ↩

-

Mo Da 莫达, “Bei yiwang de Yinni yishujia: ‘Suoluo He song’ de zuozhe Ma Er Duo Ni Ya Zuo” 被遗忘的印尼艺术家:“梭罗河颂”的作者玛尔多尼亚佐 [A forgotten Indonesian artist: The composer of ‘Bengawan Solo’, Martohartono], Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 10 December 1953, 8; Sun Bin Lin 孙彬琳, “Souji Yinni minge de changshi” 搜集印尼民歌的尝试 [The attempt to collect Indonesian folk songs], Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 18 December 1953, 8; Wei Zhi 微知, “Yinni yinyue zhi wojian” 印尼音乐之我见 [My views on Indonesian music], Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 7 January 1954, 8. (Microfilm NL2702) ↩

-

Bai Xu 白絮, “Saodang seqingkuang” 扫荡色情狂 [Eradicating the perverts], Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 17 November 1953, 9. (Microfilm NL2701) ↩

-

Bin Bing 斌冰, “Biye hou de chulu wenti” 毕业后的出路问题 [The future after graduation], Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 22 December 1953, 9. (Microfilm NL2701) ↩

-

Yao Zi 姚紫, “Huang Yi jun de fenkai, weimian you xie tianzhen” 黄裔君的愤慨,未免有些”天真” [The anger from Mr Huang Yi seems to be a little “naïve”], Shi Ji Lu 世纪路, 20 November 1953, 9. ↩

-

Throughout Xing Ying’s editorial career, he successfully kept his supplements running for a healthy lifespan. Luo, Xing Ying yanjiu zhuanji, 117. ↩

-

Qing Nian Wen Yi had over 700 issues in seven and a half years, publishing more than one issue each week. ↩

-

Mark Twain, “Wo zenyang kaishi xie wenzhang: Ma Ke Tu Wen de zixuan” 我怎样开始写文章:马克吐温的自选 [How I start writing essays: Mark Twain’s selection], Qing Nian Wen Yi 青年文艺, 17 May 1961, 17. (Microfilm NL2768) ↩

-

The lectures included “The New and Old of Japanese Culture” (日本文化的新与旧), “The Meiji Restoration and Modern Japan” (明治维新和现代日本), “Confucian Doctrine in Japan” (孔子学说在日本), “Japanese Buddhism” (日本的佛教), “Towards a Great Japan” (走向一个伟大的日本), and “Japanese Customs and Traditions” (日本的风俗习俗). The contents of these lectures were subsequently published in Nanyang Siang Pau. Zhuang Ming Xuan 庄明萱, “Xing Ying lun” 杏影论 [A discussion on Xing Ying], in Luo, Xing Ying yanjiu zhuanji, 88. ↩

-

“Xian gei Gangguo” 献给刚果 [Dedicated to Congo], Qing Nian Wen Yi 青年文艺, 8 March 1961, 15. (Microfilm NL2766) ↩

-

Ismail Hussein, “Dong Ge Hua Lan: Jiechu de Malai shiren” 东革·华兰: 杰出的马来诗人 [An outstanding Malay poet: Tongkat Warrant], trans. Ye Ren Shi 椰人试, Qing Nian Wen Yi 青年文艺, 14 August 1961, 17 (Microfilm NL3319); and M. Zain Salleh, “Jianshe shiqi de wenxue de renwu” 建设时期的文学的任务 [The mission of literature during nation building], trans. Ma Li 马里, Qing Nian Wen Yi 青年文艺, 8 May 1961, 17. (Microfilm NL3319) ↩

-

Bi Cheng 碧澄, “Yisa Hazhi Muhamo: Yi wei qin yu xiezuo de Malai zuojia” 依萨哈芝穆哈末: 一位勤于写作的马来作家 [Ishak Haji Muhammad: A hardworking Malay writer], Qing Nian Wen Yi 青年文艺, 25 December 1961, 18. (Microfilm NL3319) ↩

-

Yao Zi 姚紫, “Duzhe, zuozhe, bianzhe” 读者、作者、编者 [Reader, author, editor], Zhou Mo Qing Nian 周末青年, 22 November 1952, 3. ↩

-

Yao, “Duzhe, zuozhe, bianzhe.” ↩

-

Li Jian 李建, “Gejiao de gongren” 割胶的工人 [The rubber tappers], Zhou Mo Qing Nian 周末青年, 29 November 1952, 3; Yuan Yuan 媛媛, “Shiye” 失业 [Unemployment], Zhou Mo Qing Nian 周末青年, 6 December 1952, 3. ↩

-

Zhou Mo Qing Nian 周末青年, 29 November 1952, 3. ↩

-

Qin Kai 秦凯. “Tougao shibai geiwo de jingyan” 投稿失败给我的经验 [My experience with manuscript rejection], Zhou Mo Qing Nian 周末青年, 6 December 1952, 3. ↩

-

“我需要再声明一下:“‘青年广场’不是私人泄愤的地方,也不是意气用事的地方。它主要的用意在于:推使马华教育进步到合法合理的境界。也就因为这样,我们才要求:有冤屈、可申诉;遇到不合理的事象,可抨击。使一些不可阐明的学校当局不致‘关起大门,作威作福’。” Zhou Mo Qing Nian 周末青年, 12 December 1952, 3. ↩

-

Li Ru 李儒, “Tingxue yi xueqi, ye yao jiao xuefei, zhi xu xiansheng ma, buzhun xuesheng ai” 停学一学期,也要交学费,只许先生骂,不准学生哀 [Lessons on hold for a semester, but school fees still charged: Teachers allowed to reprimand, students not allowed to cry foul], Zhou Mo Qing Nian 周末青年, 6 December 1952, 3. ↩

-

Han Jiang 韩江, “Jinzhi nannü tanhua, jiancha xuesheng xinjian, ruci weifeng xiaozhang, kaiyou pijiu liang zhi” 禁止男女谈话,检查学生信件,如此威风校长,揩油啤酒两支 [Bans conversation between boys and girls, reads students’ letters: High-handed principal takes petty advantage with two bottles of beer], Zhou Mo Qing Nian 周末青年, 13 December 1952, 3; Hua Ren 化人, “Tougao qi fengbo, xiaozhang you quan neng shigui, siwen jin saodi, bianzhe wuliang zuo bangxiong” 投稿起风波,校长有权能使鬼,斯文尽扫地,编者无良作帮凶 [Article submission stirs up a storm: Principal with power to manipulate, propriety a façade, editor as accomplice], Zhou Mo Qing Nian 周末青年, 27 December 1925, 3. ↩

-

Poetry special column in Zhou Mo Qing Nian 周末青年, 12 December 1952, 3; 13 December 1952, 3; and 27 December 1952, 3. ↩

-

Xing Ying 杏影, “Xin Miao Mailbox,” Xin Miao 新苗, 4 March 1958, 15. (Microfilm NL2736) ↩

-

Xing Ying 杏影, “Guanyu Xin Miao de chuangkan” 关于《新苗》的创刊 [About the start of Xin Miao], Xin Miao 新苗, 1 March 1958, 8. (Microfilm NL2735) ↩

-

Liu Shun 柳舜, “Ta buhui jimo” 他不会寂寞 [He will not be lonely], in Luo, Xing Ying yanjiu zhuanji, 114. ↩

-

Yang Zhi 杨之, “Wo de diyici lüxing” 我的第一次旅行 [My first overseas trip], Xin Miao 新苗, 4 March 1958, 17. (Microfilm NL2736) ↩

-

Lao Er 老二, “Diyici ceyan” 第一次测验 [The first attempt]; Wen Sheng 文声, “Mangguo” 芒果 [Mango]; Xian Ming 冼明, “Tuzi, lang, daxiang, huli” 兔子·狼·大象·狐狸 [Rabbit, wolf, elephant, fox]; and Huang Feng 黄奉, “Zai jiaolin li” 在胶林里 [In the rubber plantation], Xin Miao 新苗, 15 March 1958, 19. (Microfilm NL2736) ↩

-

Xue Li Si 学裏思, “Xinma de yibufen diceng shenghuo” 新马的一部分底层生活 [Living in the lower class in Singapore and Malaya], Xin Miao 新苗, 4 March 1958, 15; Xiao Yun 小韵, “Shang basha” 上巴刹 [To the wet market], Xin Miao 新苗, 8 March 1958; Zhu Ying 竹影, “Wo de xiangcun” 我的乡村 [My village], Xin Miao 新苗, 11 March 1958, 18; Hong Xing 红星, “Yalong de huozai” 芽笼的火灾 [A fire in Geylang], Xin Miao 新苗, 19 April 1958, 18; Gao Bang 高邦, “Nühuangzhen” 女皇镇 [Queenstown], Xin Miao 新苗, 27 March 1958. (Microfilm NL2742) ↩

-

Huang Hun 黄昏, “Yaolanqu” 摇篮曲 [Lullaby], lyrics by Hu Yang 湖洋, Xin Miao 新苗, 10 June 1958, 17; Huang Hun 黄昏, “Ziye” 子夜 [Midnight], lyrics by Hu Yang 湖洋, Xin Miao 新苗, 25 March 1958, 18; Huang Hun 黄昏, “Muqin jiao wo yi shou erge” 母亲教我一首儿歌 [A nursery rhyme my mother taught me], lyrics by Hu Yang 湖洋, Xin Miao 新苗, 11 March 1958, 18; Huang Hun 黄昏, “Tianyuan fang cao” 田园芳草 [Idyllic fields], lyrics by Hu Yang 湖洋, Xin Miao 新苗, 15 March 1958, 19. (Microfilm NL2742) ↩

-

Gao Xiu 高秀, “Yu youren xue yinyue” 与友人学音乐 [Learning music with friends], Xin Miao 新苗, 10 June 1958, 17; Yu Si Yi 余思毅, “Yinyue yu rensheng,” 音乐与人生 [Music and life], Xin Miao 新苗, 20 March 1958, 15; Bai Li Shan 白里山, “Wo kan ‘Pao Lü’: Zhongguo minjian wudao” 我看《跑驴》: 中国民间舞蹈 [My view on ‘Running Donkey’: Chinese folk dance], Xin Miao 新苗, 24 May 1958, 15; Shan Ba Zi 山芭子, “Xin xiaoshe ge” 新校舍歌 [The new school song], Xin Miao 新苗, 15 May 1958, 15. (Microfilm NL2743) ↩