The Circulation of Premodern Knowledge Of Singapore And Its Straits Before 1819

Introduction

In 1907, the British colonial official Frank Swettenham expressed his surprise that in the 600 years between the fall of Temasek and the founding of a trading post on the island, no European had enough curiosity and application to learn about Singapore’s history nor recognised its potential as a strategic site.1 Swettenham was implicitly suggesting that there was knowledge in circulation. All it took was a little snooping about, and he was right; references to Singapore or its straits can be easily found in European literature before 1819.

Swettenham was not the only one to have recognised these references. Other scholars had too, but they were disparaging of their value. Kenneth Tregonning, then Raffles Professor of History at the University of Singapore, famously dismissed the study of precolonial Singapore in 1969 as being of no relevance and “of antiquarian interest only”.2 Later historians such as Mary Turnbull and Lim Joo-Jock were equally unenthusiastic about a search for Singapore’s older roots, adding that the historical record relating to Singapore and its straits before the 19th century was not only scarce but also fragmentary, vague and contradictory.3 Not only was making sense of these references of premodern Singapore discouraged, it was also seen as unfashionable and unprofitable.4

However, the scholarship in the past three decades has challenged these assumptions. Archaeological work and archival research, in particular, have shown that there was a thriving settlement and that precolonial Singapore was not as irrelevant as once assumed.5 As more testimonies come to light, historians are now working towards unifying them into the longer narrative of Singapore’s past.6 Despite this progress, we have yet to tackle these references found in European literature, as hinted at by Swettenham long ago. Hence the objective of this paper is to collect these references related to Singapore and its straits in European literature and question whether they are as scarce, fragmentary, vague and contradictory as formerly supposed.

Lim Joo-Jock had in 1991 suggested two possible approaches: either one can summarise all the available evidence and present them in chronological order, or one can focus on the tangible pieces and draw a series of insights from them.7 Sophie Sim has rightly deemed these approaches insufficient, because they lack critical analysis and fail to deal with the power and ambiguities of memory.8 Here I adapt these suggestions and perspectives in the following manner. First, I quantify the references about Singapore or its straits in European literature, focusing on the genre of these publications, the languages they were published in, and their growth in numbers by the century. What emerges is clear: these references are not as scarce as previously thought. Second, through a close reading of these references in European literature, I present the impressions a European reader would have had of Singapore before 1819. Finally, in putting these references together across three centuries, I argue that they should not be dismissed, because they offer us ways to rethink Singapore’s history and contain important clues for charting the future of Singapore’s pasts.

Quantifying Knowledge

Unlike what earlier historians have suggested, references to Singapore and its straits are both copious and varied. Today we can count close to 400 published works that include a reference to either Singapore or its straits before 1819, sometimes both, and these works range from chronicles and travelogues to poetry and fiction. The large number of publications containing references shows that there was sufficient knowledge circulating in European literature. Several of these, like European travelogues, sailing rutters, and chronicles have been explored in detail and have been used to reconstruct Singapore’s past before 1819. Other references can be found in religious accounts, magazines, pamphlets, periodicals, journals, plays and anthologies, but not all have been studied in detail. The sheer number of references points to a widespread cognizance of Singapore, if not of the region. A very large number of references (about 153) are contained in compendia, a category that has escaped attention so far. Comprising publications such as geographies, cosmographies, dictionaries, lexicons and encyclopaedias, the compendia helped condense and transmit knowledge of Singapore and showed how the general reader understood “Singapore” at a particular point in time.

Singapore and its straits feature several times in fiction, such as in the novels of Daniel Defoe, and can be found in Spanish, Portuguese and Dutch poems as well.9 Despite the small number of such publications (about 16 so far), they point to creative imaginings of Singapore before the modern period.10 Another important genre of knowledge is the travel anthology. Narratives and accounts were plucked from different sources spanning various languages, regions and periods, and compiled into volumes of collected travels. Europe has a long tradition of publishing collected travel accounts, which were often lavishly illustrated and extremely costly.11 By the 18th century, the genre gained popularity and increased in circulation. For example, the four-volume travel compendium, A Collection of Voyages and Travels, first issued in 1704 by the brothers Awnsham and John Churchill, was reprinted with two additional volumes in 1732. A third edition appeared in 1744–46, followed by a fourth in 1752, published by the bookseller Thomas Osborne.12 Although this repackaging increased the spread of knowledge of Singapore and its straits, it also had the effect of recycling existing knowledge for new readers.

These references are also found in different languages and point to a wide dispersion and transmission of knowledge across Europe. There is a substantial number of references to Singapore and its straits in Latin, especially in the 16th century, when Latin functioned as a scholarly language for learning. Latin publications with references to Singapore were often initially textual aids to cartographic material. Later Latin publications provided more detail, with many describing Singapore as a city within the Kingdom of Siam. An important work written in Latin were the letters of St. Francis Xavier (1506–52), a celebrated Jesuit who travelled to the Far East. His letters dispatched when he was anchored off Singapore (“ex freto Syncapurano”, Latin for “from the Straits of Singapore”) helped reinforce the knowledge in religious circles that Singapore was an important station up to the 19th century.13 After 1650, the Romance and Germanic vernaculars began to replace Latin, and more references to Singapore appeared in publications in Spanish, Italian, Portuguese, French, English, German and Dutch. At present, there are many collected publications in English and French, but larger-than-expected numbers in these languages might simply reflect current digitisation efforts. It is clear from tracing the circulation of information that these references were often drawn from a similar set of sources. For example, English descriptions of the Malay Peninsula, Singapore and its straits depended heavily on information provided by English travellers such as William Dampier and Alexander Hamilton. On the other hand, French publications relied on knowledge translated into French. Pierre d’Avity’s Le Monde (The World), a popular and widely read publication in the early 17th century, contains references to Singapore and the wider straits region. But a closer examination shows that this information was extensively compiled from the works of the Portuguese historian João de Barros and the French Jesuit Pierre du Jarric.14 This overreliance on a few transmitted sources perhaps testifies to how little was known in England and France about Singapore and its straits before 1819.

Finally, references to Singapore and its straits increased from the 16th to 18th century, which reflected developments in the print industry and the growing demand for travel literature. In the 16th century, references to Singapore and its straits were still limited to the Portuguese chronicles, translated or otherwise, and a few religious accounts. This number increased with time. By the 1560s, an increasing number of cosmographies and geographies, mostly written in Latin, became popular, a development that mirrored the broader curiosity and interest in the wider world. By the end of the 17th century, references that touch on Singapore and its straits had doubled in number. This growth was spurred by the increasing voyages to and writing of the East and also by the development of the book trade in major centres such as London, Paris and the Low Countries.15 As Daniel Roche has shown, European printers published 1,566 travelogues in the 17th century compared to 456 a century before. By the end of the 18th century, the number of travelogues had more than doubled to 3,540. This development added considerably to the knowledge base of Singapore and the wider straits region.16 The 18th century was the age when knowledge of Singapore and its straits reached the growing masses. Technical innovations in publishing, increased mobility, the development of scientific societies, and an expanding base of readership meant that more references than before reached curious audiences.

Qualifying Knowledge

However, the number of references to Singapore and/or its straits does not always mean that they contain a wealth of detail. Many publications contain no more than a name and tell us little about the island or its history. That said, regardless of length and detail, the reader of the literature would have possibly formed four impressions of Singapore. These impressions were consistent within European publications before 1819 and can be summed as such: Singapore was a place of danger, division, antiquity and concentration. The impressions occasionally overlap but hardly deviate from these patterns of description.

A place of danger

The immediate impression a reader would have had of Singapore and its straits was that it was a place of great danger. A combination of fierce storms, difficult seascape, and vulnerability to ambush led the area around Singapore, in particular its channel, to gain a certain notoriety. The Portuguese writers João de Barros and Brás de Albuquerque referred to Singapore as falsa demora, which meant a tricky place to interrupt one’s voyage or a place where ships were lost while waiting.17 Irregular and rapid tides, hidden sandbanks and treacherous rocks made navigation risky and caused many ships to meet with shipwreck. The ships carrying the Japanese Tenshō embassy to Rome in 1584 met with such a mishap, hitting a shallow rock in the Singapore straits and losing their valuable cargo, although the crew was thankfully saved from danger.18 Another account was penned by the Spanish Dominican priest Domingo Navarrete, who crossed the straits of Singapore around the mid-17th century. Navarrete wrote, too, about how other sailors in Canton faced difficulties in sailing through the narrow passage and overdramatised the violent currents that “whirl’d a ship about with its sails abroad”.19 When the Italian priest Matteo Ripa travelled from Melaka to Manila in 1708, the Armenian ship he was on hit submerged rocks in shallow waters and was about to founder off the island of Singapore. Matteo was said to have performed a miracle, and the ship eventually sailed on safely.20 These three incidents from three different centuries are some of the many incidents that made plain to readers the dangers of geography around Singapore.

There were also numerous instances of local attacks on Europeans in the Singapore region. Readers today would be familiar with the account of Jacques de Coutre (not published until the 20th century), who was ambushed by Orang Laut vessels off present-day Sentosa in the 17th century.21 Yet his account was not unique. European readers back then could read the account of Portuguese priest Melchior Barreto, who was attacked en route to Macao in the 16th century. When Barreto’s Portuguese caravel ran aground in the Singapore straits in April 1555, the party was attacked by 50 local Orang Laut perahu22 that fell upon them with loud screams.23 Occasionally, the area in and around Singapore was the setting for battles between Malay kingdoms and became perilous for Europeans caught in the crossfire. For example, the Spanish Friar Diego Aduarte witnessed 80 large galleys belonging to the Sultan of Aceh pitched for battle in the Singapore straits against those of Johor.24 The incoming Governor of Macao, Antonio de Albuquerque Coelho, who wintered in Johor in 1717, wrote his account of Raja Kecil of Siak, who assembled a large and powerful fleet at the mouth of the Singapore straits in preparation to conquer Johor.25 These accounts in European literature undoubtedly helped to shape the perception of Singapore and its straits as a place of mortal danger.

A place of division

As geographical knowledge expanded with discovery and conquest, early European cartographers and geographers tried to reconcile the new information with existing knowledge from ancient Ptolemaic geography. As sailors relied on visual landmarks to navigate past the maze of islands at the tip of the Malay Peninsula, prominent outcroppings such as Batu Berlayar (Batu Berlayar Point, Labrador Park) and Pedra Branca, as well as hilly landforms such as Mount Berbukit (Bukit Pelali, Pengarang) and Romania Point (Tanjung Penyusop) in the region became important navigation markers. This information likely circulated back to Europe and created the misperception that one of the elevated landforms was Singapore, which agreed with Ptolemy’s 2nd-century description of a cape and city located at the southernmost tip of Asia. Singapore thus came to be referenced as a cape from the 16th century onwards.

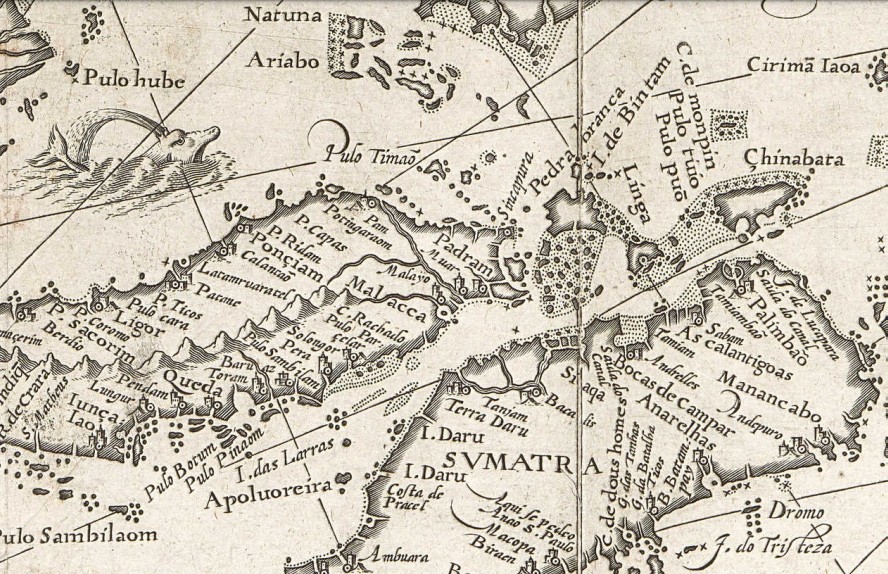

Singapore’s mistaken identification as a prominent promontory in texts and maps led to it being taken as a notional marker of division. Singapore was cited in the Portuguese poem, Os Lusíadas by Luís Vaz de Camões (1572), as a turning point, and João de Barros’s Da Ásia (1562) divided the sixth and the seventh part of the East Indies from “Cape Singapura”.26 This divisional marker was adopted by later writers such as Faria y Sousa (1666–75) and the geographer Pierre Duval, the editor of François Pyrard’s travelogue (1679).27 Other writers made this distinction for practical reasons, since two maritime zones (the South China Sea and the Bay of Bengal) overlapped around the Singapore region.28 This idea of transition is memorably expressed in Albuquerque’s Commentaries (1576), which referenced Portuguese ships arriving at the “gate” (porta) of Singapore, demarcating a point of crossing.29 The repeated assertions created by cartography and writing reinforced the mental geography of Singapore and its straits as a dividing point between two different regions of Asia (Figure 1).

Besides dividing the two maritime zones, the “cape” of Singapore was also seen as separating the Asian mainland from the island world of Southeast Asia, notably from Sumatra and Java. Thomas Herbert’s observation that Singapore was a former trading town that marked the southernly cape of the Asian continent and divided it from Sumatra was a common impression at the time. This statement would become the standard definition in most encyclopaedia and dictionary entries in the 18th century.30 These assumptions of Singapore as a cape and dividing marker came to be deeply entrenched in European thought and proved resilient well into the 19th century.

A place of antiquity

As Swettenham had surmised, Europeans had access to knowledge about Singapore’s antiquity. We can trace two strands of knowledge: from the Portuguese chronicles in the 16th century and through the Dutch minister François Valentijn’s writings in the early 18th century. Several Portuguese writers in the early 16th century, such as João de Barros and Brás de Albuquerque, had written parts of Singapore’s early history. This knowledge of Singapore’s antiquity did not arise from an intrinsic interest in Singapore’s past per se, but was prompted by concerns over administering Melaka as a new Portuguese colony after its capture in 1511. The broad outline of this story focuses on the exploits of Parameswara, particularly his flight from Palembang after his unsuccessful revolt, his arrival in Singapore, the subsequent murder of his host and usurpation of both the kingship and kingdom. After being driven out of Singapore, he went on to establish Melaka, which became famous as a trading emporium. This information likely stemmed from the oral accounts that the Portuguese collected after becoming masters of the port and town of Melaka. This knowledge sheds light on not only Singapore’s antiquity, but also its connections with the wider Malay world.31

These Portuguese writings circulated throughout Europe, spreading knowledge of Singapore and the wider straits region to curious audiences.

One such circuit took it to 16th-century Italy, to humanist centres such as Florence and Venice.32 Barros’s account (1562) was translated into Italian within a year and was cited by the geographer Giovanni Battista Ramusio.33 Ramusio was an avid collector and compiled his own set of travel writings, including an abridged extract of the Portuguese apothecary Tomé Pires’s Suma Oriental (1512–15), a work not published until 1944.34 Other snippets of the Singapore story found in Barros’s or Albuquerque’s accounts were cited in the celebrated Cosmographia (1628), attributed to the German geographer Sebastian Münster, bringing knowledge to German readership.35 Another circuit of knowledge took it to France and England. The French traveller Vincent le Blanc’s account (1662), for example, mentioned “a certain tyrant who had wanted to seize the state of Singapore […] which was the entry to all the Orient and commanded the whole country”.36 Similarly, the third volume of the English cleric Peter Heylyn’s Cosmographie (1652) contained an account of Parameswara, which also explained how Singapore could be considered as the mother of Melaka.37 These three accounts of the 17th century show how far knowledge originating from Portuguese writings of Singapore and its straits had circulated.

In the 18th century, Barros’s and Albuquerque’s accounts found a new outlet and audience through reprinted travel collections. The most comprehensive anthologies were published by the Leiden publisher Van der Aa in the 1700s, with various other snippets and extracts republished in other popular collected volumes, such as the Churchill brothers’ A Collection of Voyages and Travels (1704) and The Modern Part of an Universal History (1759–66).38

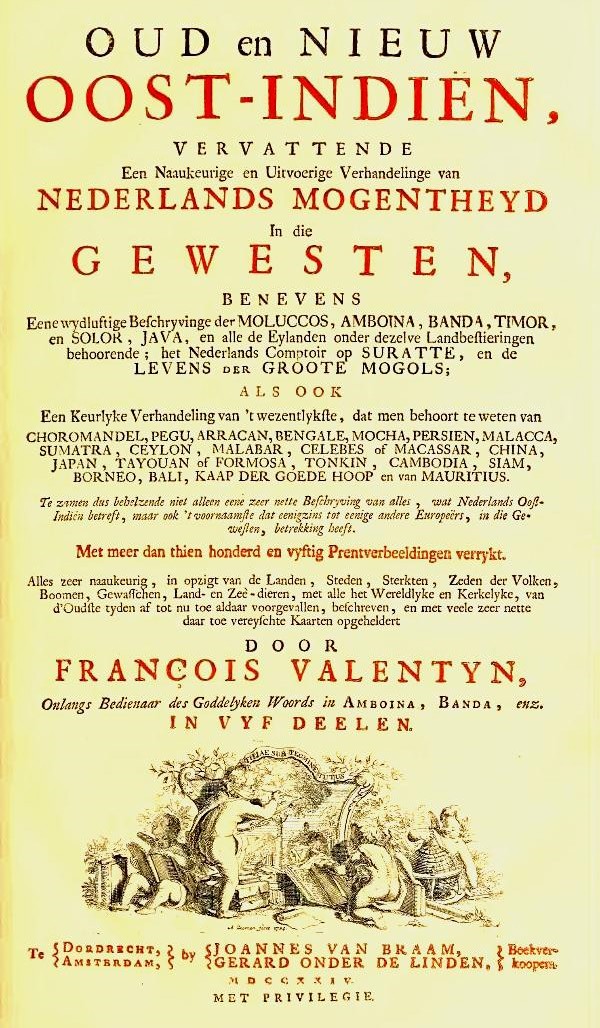

A second strand of knowledge came from Valentijn’s influential publication, Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indiën (Old and New East-Indies; 1724–26) (Figure 2). In composing his work, Valentijn acquired and referred to several Malay manuscripts, such as the Hikayat Hang Tuah(c. 1688–1710) and the Sulalat-us Salatin (c. 1612).39 By drawing on these sources, Valentijn conveyed to his readers that Singapore was not only the first city or town of the Malays that moreover lent its name to the nearby straits, but also the seat of several kings before its transfer to Melaka.40 This knowledge was later cited in several compendia of the late 18th century and consulted by several prominent writers.41 Through the knowledge distilled from acquired Malay manuscripts and the reprints of old Portuguese chronicles, the majority of readers came to know of or became familiar with the straits region and Singapore’s early history.

A place of concentration

Finally, Singapore and its straits have long been considered a place of strategic significance. Singapore’s position straddling two maritime zones

has made it a key conduit for world shipping and a meeting place for cultures and societies. However, the area around Singapore was also a strategic bottleneck to concentrate military forces to harass competitors or jostle for influence. The importance of controlling the area around Singapore was not lost on the European powers. The Dutch, Portuguese and even the Spanish had considered establishing forts in the vicinity and had on various occasions gathered forces off Singapore.42

Portuguese ships blockaded and fought around the Johor River in the 16th century. The Dutch gathered there and captured the richly laden Portuguese carrack Santa Catarina in 1603 off the coast of Singapore, where the Spanish armada also assembled in 1616. These exploits of large sea forces concentrated around Singapore could be read in the European literature of the day.43 (Figure 3)44

In the 17th century, the Dutch identified Singapore and its straits as a strategic chokepoint of world trade and sent jachten45 and sloops to cruise in and around the area. The high points of Dutch concentration were during the early years of the offensive (1602–09) and the period when they stepped up their attempts to capture Portuguese Melaka (1633–41). Dutch ships were instructed to secure their shipping lines, while disrupting those of the Portuguese.46 Because of the success of this operation, Singapore or the area around it became known, especially in Iberian travel literature, as a place where the Dutch concentrated their forces. A good number of travel accounts were written by priests harassed by Dutch ships while en route to China or Japan. For example, the Portuguese priest Gil de Abreu was captured in the Singapore straits and imprisoned in Batavia.47 The Italian Jesuit Marcello Mastril was more fortunate, narrowly escaping capture by three Dutch ships in the area in 1636.48 One such battle with the “Hollanders who fought with valiant spirits around Singapore” was memorialised by the Portuguese Miguel Botelho de Carvalho in the Spanish poem, La Filis (1641).49

After the Dutch took Melaka in 1641 and gained ascendancy in the East Indies, references in the European literature of the 17th and 18th centuries continued to complain about Dutch concentration and control of the waters in and around Singapore. Jean Chardin, the French jeweller, wrote in his travelogue how Indian ships had to obtain passports from the Dutch “through favour, recommendations and presents” before they could pass through the Singapore straits.50 Spain and Portugal, which had colonial outposts in Manila and Macau and maintained trade with China, also opined negative views of Dutch control and their concentration of ships in the straits region. For example, the Historical Extract of Antonio José Alvarez de Abreu, a study of commercial relations between the Philippines and Spain published in 1736, states this plainly: “The commerce of these two cities [Manila and Macau] is sustained by the Strait of Singapore, and always at risk of the Dutch.”51 This opinion of Dutch concentration of ships in the region is also prevalent in other European writings of the 18th century.

Questioning Knowledge

Having examined the number and types of references to Singapore and its straits before 1819, and the four consistent impressions that a premodern European reader would have formed, we can now ask: what role do these references have to play in the context of Singapore’s history? There are four main ways that these references in European literature can still be useful for rethinking and writing about Singapore’s past.

A bridgehead

As suggested by other scholars, these references help us to connect Singapore’s pre-1819 past with its present and clarify its place in the region. Historians today are identifying and retrieving materials relevant to Singapore to build a longer 700-year history. Although the post-1819 historical narrative is still more substantial, the more detailed references found in European literature help add more episodes and evidence that testify to Singapore’s precolonial past.52 The other smaller and less descriptive references might not always indicate settlement and activity on the island, but they nevertheless help us to better contextualise Singapore within the region and (re)consider its connections to other places in Southeast Asia.53 Furthermore, some scholars argue that Singapore can be seen to have repeatedly reinvented itself in response to the geographical and cultural changes, with notable up-and-down cycles.54 These references testify that in the three centuries before 1819, even though we know little about what was happening on the island, Singapore was far from forgotten and still made an impression in the thoughts of readers far away in Europe.

Formation of knowledge

These references also provide a first step towards understanding the formation of knowledge of Singapore and its straits. By looking at how knowledge was formed and circulated through these references, we better understand how we arrived at vague and contradictory descriptions of Singapore before 1819.

The first reason has to do with the elasticity of the name. European travellers applied the name to a variety of landforms and seascapes in and around the Singapore region, which has led to confusion over what exactly is being referred to. A second reason has to do with the growth of different strands of knowledge. While in the early 16th century references to Singapore as a city and cape arose because writers attempted to reconcile newer discoveries with classical Ptolemaic knowledge,55 the Portuguese chronicles and later travel writing were responsible for putting into circulation knowledge about Singapore’s earlier incarnations as a strait, capital and kingdom. The result was several competing descriptions or definitions of Singapore, which led to significant confusion regarding Singapore as a place in time. It is sometimes possible to read these errors or inconsistencies within the same publication. For example, in the celebrated Dutch collection of voyages, Begin en Voortgangh van de Oost-Indische Compagnie (Origin and progress of the Dutch East India Company; 1646) by the Amsterdam publisher Isaac Commelin, Singapore appears in the course of 17 pages as a city (stadt), a cape (cabo), a strait (strate) and a village (dorp).56 It is clear that these references to Singapore and its straits reflect a mix of current, classical and historical knowledge – all in the same work. A third reason has to do with the transmission of knowledge, which increased confusion about Singapore over time. Writers who had never visited the East Indies wrote about these places based on the books that were at their disposal. Even though this demonstrated engagement with knowledge of Singapore and increased the number of references, they also multiplied the confusion already extant in publications.57 And as dictionaries and encyclopaedias began to proliferate on the market in the 18th century, compilers began to draw information from various travel accounts and publications to produce standardised definitions of peoples, places and things.58 Because various definitions were repeatedly copied and rearranged in disregard of time and context, these entries lost touch with the realities they described. In many compendia, it would not be out of place to read this entry on Singapore found in the Encyclopaedia Perthensis, published in 1816, just three years before the founding of a British trading post in Singapore.

Sincapora, Sincapoura, or Sincapura. An island and cape, with its capital on the S[outh] coast of Melaka; opposite Sumatra.

Sincapura, Straits of, a narrow channel between the above island, Melaka and Sumatra.59

The three spellings of Singapore and four different definitions of Singapore – as a strait, an island, a cape and a capital – represent the wisdom and errors of three centuries of acquiring and circulating knowledge, which had swelled to the point of confusion and contradiction. These entries patently show that the European records of Singapore and its straits are not sequenced according to the internal developments of the region and its peoples, but have become jumbled up with other realities that have little to do with its past.

New ideas and old assumptions

Third, these references help us to generate new ideas and discard older assumptions about Singapore. The four impressions that a European reader would have had of Singapore and its straits do not support the idea that Singapore appears after 440 years of neglect as a knowable and distinct place in history.60 Singapore had always been a knowable place not only in the region but also to European audiences, despite British claims that Singapore was terra incognita. In addition, our current impressions of Singapore as a point of division, as a strategic location and a place of antiquity are shown here to have been in circulation for a long time and shaped by literary engagement. Beyond casting aside older views, these references can also help to illuminate older and forgotten connections. For example, references to Singapore as a city of Siam hint at a deeper relationship between ancient Singapore and Thailand. Comparing these references might also help produce connected histories that tell us more about Singapore’s past. In their travel accounts, Alonso Ramirez and William Dampier both noted passing Singapore around 1687. Dampier benefited from refreshments from the Orang Laut, while Ramirez attacked them.61 Seen separately, the accounts tell us little, but taken together, they point towards a period of intense activity in and around the Singapore region. The chances of finding other connections are small but not improbable. It must be cautioned, however, that these European references to Singapore and its straits cannot stand alone; they must be corroborated, too, with other Asian texts and evidence to produce a more complete picture.

The future of Singapore’s past

Finally, these references can serve as an oracle for the future of Singapore’s past(s). With increased digitisation of publications and greater online accessibility to these materials, more references of Singapore, if not of its straits and the wider straits region, are almost certain to be found. This is true not only of European literature but also other manuscripts, languages and archives, many of which are not covered here.62 Furthermore, references to Singapore might not always be found under this name. In the European records, it is not uncommon to find references to Lange Eilant (Long Island) or Pulau Panjang, designations which also appear on hydrographic charts before 1819. The Portuguese writers also used the term Ujantana (Ujong Tanah) to refer to the area around Singapore. With careful reading and sufficient contextual knowledge, these references can also be added to our knowledge of Singapore, or the Singapore region.63

However, it is clear from these references that the European writers had a peripheral vision of Singapore and its straits and did not always tell us what we would like to know about its past. The published literature contains little about activity on the island, because the writers rarely visited it and had little interest or extended experience of the region at large. The Europeans wrote only about the things they knew and experienced and often repeated what was already known.64 This is why the four impressions stated above will likely continue to characterise other references to Singapore and its straits in European literature.

Conclusion

Ultimately, these references to Singapore reveal the current constructs for understanding its past. But the quest to make meaning is only just beginning. As Peter Preston reminds us, there is no one Singapore: context is key.65 If we define Singapore as just the island, then the historical record before 1819 is indeed scarce, fragmentary, vague and contradictory. But if we look for an idea of Singapore that goes beyond the island and ask more searching questions about the pieces that we find, then we might come to a better understanding of what Singapore is and can mean in the past.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Professors Peter Borschberg and Kwa Chong Guan for their feedback and suggestions on an earlier draft and the library staff at the National Library of Singapore for facilitating access to materials. In particular, Joanna Tan, Timothy Pwee and Heirwin bin Mohd Nasir have been a great help during the course of my research. I would also like to thank Dr Seah Cheng Ta for the company and conversations throughout my fellowship stint at the library.

Benjamin J. Q. Khoo is a research associate at the Asia Research Institute, National

University of Singapore. He holds a BA in history and European studies from the

National University of Singapore, and an MA in colonial and global history from

Leiden University. A former Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow, Benjamin studies

the histories of the early modern world, with a focus on networks of knowledge and

diplomatic encounters in Asia.

Benjamin J. Q. Khoo is a research associate at the Asia Research Institute, National

University of Singapore. He holds a BA in history and European studies from the

National University of Singapore, and an MA in colonial and global history from

Leiden University. A former Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow, Benjamin studies

the histories of the early modern world, with a focus on networks of knowledge and

diplomatic encounters in Asia.Bibliography

Abreu, Antonio José Alvarez De. Extracto Historial Del Expediente Que Pende En El Consejo Real, Y Supremo De Las Indias, a Instancia de la Ciudad De Manila, Y Demas De Las Islas Philipinas [Historical Extract of the Record pending in the Royal and Supreme Council of the Indies, at the request of the City of Manila, and Others of the Philippine Islands]. Madrid: Juan de Ariztia, 1736.

Aduarte, Diego De. Tomo Primero de la Historia de la Provincia Del Santo Rosario De Filipinas, Iapon Y China, de la Sagrada Orden De Predicadores [First volume of the history of the province of Santo Rosario of the Philippines, Japan and China, of the Sacred Order of Preachers]. Zaragoça: por Domingo Gasçon, 1693.

Albuquerque, Brás De. Commentarios Do Grande Afonso Dalboquerque, Capitão Gerai Que Foi Das Indias Orientaes Em Tempo Do Muito Poderoso Rey D. Manuel, O Primeiro Deste Nome, Parte III [Commentaries of the Great Afonso Dalboquerque, who was Captain- General of the East Indies in the time of the very powerful King D. Manuel, the first of his name, part three]. Lisboa: Na Regia Officina Typografica, 1774. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 946.902 ALB)

Anonymous. Diversi Avisi Particolari dall’Indie Di Portogallo Ricevuti, Dall’anno 1551 Fino Al 1558 Dalli Reverendi Padri Della Compagnia Di Giesu [Various special reports from the Indies of Portugal received from the year 1551 to 1558 by the Reverend Fathers of the Company of Jesus]. Vol. 1. Venice: Michele Tramezzino, 1565.

Anonymous. Encyclopedia Perthensis, etc. 2nd ed. Vol. 21. Edinburgh: John Brown, etc, 1816.

Anonymous. The Modern Part of an Universal History, etc. 44 vols. London: Printed for S. Richardson et al., 1759–66.

Barros, Joao de. Da Asia De Joao De Barros, Dos Feitos, Que Os Portuguezes Fizeram No Descubrimento, E Conquista Dos Mares, E Terras Do Oriente. Decada Primeira, Parte Segunda [Asia of João de Barros: The deeds of the Portuguese in the discovery and conquest of the seas and lands of the Orient, first decade, second part]. Lisboa: Na Regia Officina Typografica, 1777. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 915.4042 BAR)

—. Dell’Asia la Seconda Deca del S. Giovanni di Barros [Asia, the second decade of João de Barros]. Venetia: Appreso Vincenzo Valgrisio, 1562.

—. Ongemeene scheeps-togten en manhafte krygs-bedryven te water en te land door Diego Lopez de Sequeira, als kapitein general en gouverneur ter voortzetting van der Portugyzen gebied en vryen koophandel in de Oost-Indien, met IX scheepen derwaarts gedaan, in ‘t jaar 1518, etc. [Remarkable naval excursions and military manoeuvres on water and land by Diego Lopez de Sequeira, as Captain General and Governor for the expansion of the Portuguese territory and free trade in the East Indies, with IX ships to the year 1518]. Leiden: Pieter van der Aa, 1707. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 910.41 BAR-[FAN])

—. Roemwaardige Scheeps-Togten En Dappere Krygs-Bedryven Ter Zee En Te Land, Onder ’T Bestuur Van Don Duarte De Menezes, Als Opperhoofd Van De Vloot En Gouverneur Van Oost-Indien, Ter Aflossing Van Den Heer Generaal Diego Lopez De Sequeira, Met XII Schepen Uit Portugaal Derwaarts Gedaan, in ’T Jaar 1521,etc. [Famous voyages and valiant war-forces at sea and on land, under the leadership of Don Duarte de Menezes, as chief of the fleet and governor of the East Indies, in replacement of the Lord General Diego Lopez de Sequeira, with XII ships from Portugal to the East Indies, in the year 1521, etc.]. Leiden: Pieter van der Aa, 1706. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 954.025 MEN-[KSC].

Bartoli, Daniello. Compendio Della Vita, E Morte Del P. Marcello Mastrilli Della Compagnia Di Giesu, etc. [Compendium of the life, and death of Fr. Marcello Mastrilli of the Company of Jesus, etc.]. Napoli: Luc’Antonio di Fusco, 1671.

Borschberg, Peter. “European Records for the History of Singapore before 1819.” In An Old New World: From the East Indies to the Founding of Singapore, 1600s–1819. Edited by Stephanie Yeo, 6–18. Singapore: National Museum of Singapore, 2019. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 NAT-[HIS])

—. The Memoirs and Memorials of Jacques de Coutre: Security, Trade and Society in 17th-Century Southeast Asia. Singapore: NUS Press, 2014. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959 COU)

—. “Portuguese, Spanish and Dutch Plans to Construct a Fort in the Straits of Singapore, ca. 1584–1625.” Archipel 65 (2003): 55–88. (From National Library Singapore,Call no. R 959.005 A) c Luso-Spanish Co-operation: The Armada of Philippine Governor Juan de Silva in the Straits of Singapore, 1616.” In Iberians in the Singapore-Melaka Area and Adjacent Regions (16th to 18th Century). Edited by Peter Borschberg, 35–62. Wiesbaden and Lisbon: Harrassowitz and Fundação Oriente, 2004. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.50046 IBE)

—. “The Seizure of the Sta. Catarina Revisited: The Portuguese Empire in Asia, VOC Politics and the Origins of the Dutch-Johor Alliance (1602–c.1616).” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 33, no. 1 (2002): 31–62.

—. The Singapore and Melaka Straits: Violence, Security and Diplomacy in the 17th Century. Singapore: NUS Press, 2010. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 911.16472 BOR)

Carvalho, Miguel Botelho de. La Filis. Madrid: Por Iuan Sanchez, 1641.

Chardin, Jean_. Voyages De Monsieur Le Chevalier, En Perse, Et Autre Lieux De L’Orient. Tome Dixieme [Travels of Sir Chevalier into Persia, and other places of the Orient]. Amsterdam: Jean Louis de Lorme, 1711.

Chong, Terence. “The Bicentennial Commemoration: Imagining and Re-imagining Singapore’s History.” Southeast Asian Affairs (2020): 323–33. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959 SAA)

Churchill, Awnsham and John Churchill. A Collection of Voyages and Travels, Some Now First Printed from Original Manuscripts, Others Now First Published in English, 6 vols. London: J. Walthoe, 1732. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 910.8 CHU)

Commelin, Isaac. Begin Ende Voortgangh Van De Vereenighde Nederlantsche Geoctroyeerde Oost-Indische Compagnie, etc., Vol. II [Origin and progress of the Dutch East India Company]. Amsterdam: n.p., 1646. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 910.9492 BEG)

Dampier, William. Dampier’s Voyages: Consisting of a New Voyage Round the World […], edited by John Masefield. London: E Grant Richards, 1906. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 910.41 DAM-[GBH])

De Camoes, Luís. Os Lusíadas [The Lusiads]. Translated by R. F. Burton. 2 vols. London: Bernard Quaritch, 1880.

Defoe, Daniel. The Life, Adventures, and Pyracies, of the Famous Captain Singleton. London: Printed for J. Brotherton, 1720.

—. A New Voyage Round the World. London: G. Read, 1730.

Delmas, Adrien. “Writing History in the Age of Discovery, According to La Popelinière, 16th–17th Centuries.” In The Dutch Trading Companies as Knowledge Networks. Edited by Siegfried Huigen, Jan L. de Jong and Elmer Kolfin, 295–318. Leiden: Brill, 2010. (From National Library Singapore, call no. R 306.4 DUT)

Lim, Arthur Joo-Jock. “Geographical Setting.” In A History of Singapore. edited by Ernest Chew and Edwin Lee, 3–14. Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1991. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 HIS-[HIS])

Lisle, Debbie. The Global Politics of Contemporary Travel Writing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Maclean, Gerald. “Early Modern Travel Writing (I): Print and Early Modern European Travel Writing.” In The Cambridge History of Travel Writing. edited by Nandini Das and Tim Youngs, 52–76. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

Marcocci, Giuseppe. The Globe on Paper: Writing Histories of the World in Renaissance Europe and the Americas. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020.

Miksic, John, and Cheryl-Ann Low Mei Gek, eds. Early Singapore, 1300s-1819: Evidence in Maps, Text, and Artefacts. Singapore: Singapore History Museum, 2005. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.5703 EAR-[HIS])

Münster, Sebastian. Cosmographia Oder Beschreibung Der Gantzen Welt etc. [Cosmography or Description of the whole World, etc.]. Facsimile reproduction of the Basel edition of 1628. Lindau: Antiqua Verlag, 1978.

Parthesius, Robert. Dutch Ships in Tropical Waters: The Development of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) Shipping Network in Asia, 1595–1660. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2010. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEAS 387.509598 PAR)

Pettegree, Andrew. “Centre and Periphery in the European Book World.” Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 6, no. 18 (2008): 101–28. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Pettegree, Andrew and Arthur der Weduwen, The Bookshop of the World: Making and Trading Books in the Dutch Golden Age. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RBUS 381.45002 PET-[BIZ])

Pinkerton, John. Modern Geography, etc. London: Printed for T. Cadell and W. Davies, etc., 1807.

Preston, Peter. Singapore in the Global System: Relationship, Structure and Change. New York: Routledge, 2012. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 306.095957 PRE)

Pyrard, François. Voyage de François Pyrard de Laval. Paris: Chez Louis Billaine, 1679.

—. The Voyage of Francois Pyrard of Laval to the East Indies, the Maldives, the Moluccas, and Brazil, edited by Albert Gray. London: Hakluyt Society, 1887. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 910.8 HAK-[GBH])

Schleck, Julia. “Forming Knowledge: Natural Philosophy and English Travel Writing.” In Travel Narratives, the New Science, and Literary Discourse, 1569–1750. Edited by Judy A. Hayden, 53–70. New York: Routledge, 2012.

Sheehan, J. J. Seventeenth-Century Visitors to the Malay Peninsula. Singapore: Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1934. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 915.95 SEV-[JSB])

Sim, Meijun Sophie. “Fishing Tales: Singapura Dilanggar Todak as Myth and History in Singapore’s Past.” Master’s thesis, National University of Singapore, 2005.

Skott, Christina. “Imagined Centrality: Sir Stamford Raffles and the Birth of Modern Singapore.” In Singapore from Temasek to the 21st Century: Reinventing the Global City. Edited by Karl Hack, Jean-Louis Margolin and Karine Delaye, 155–84. Singapore: NUS Press, 2010. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 SIN)

Swettenham, Frank. British Malaya: An Account of the Origin and Progress of British Influence in Malaya. London: George Allen and Unwin, 1948. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.5 SWE-[GBH])

NOTES

-

Frank Swettenham, British Malaya: An Account of the Origin and Progress of British Influence in Malaya (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1948), 31. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.5 SWE-[GBH]) ↩

-

K. G. Tregonning, “The Historical Background,” in Modern Singapore, ed. Ooi Jin-Bee and Chiang Hai Ding (Singapore: University of Singapore, 1969), 14 (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 OOI-[HIS]); Kwa Chong Guan, “Introduction,” in Studying Singapore before 1800, ed. Kwa Chong Guan and Peter Borschberg (Singapore: NUS Press, 2018), 2. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 STU-[HIS]) ↩

-

C. M. Turnbull, A History of Modern Singapore, 1819–2005 (Singapore: NUS Press, 2009), 20 (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 TUR-[HIS]); Arthur Joo-Jock Lim, “Geographical Setting,” in A History of Singapore, ed. Ernest C. T. Chew and Edwin Lee (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1991), 3. (From National Library Singapore, cCall no. RSING 959.57 HIS-[HIS]) ↩

-

The politician Sinnathamby Rajaratnam, for example, asserted in 1984 that to “push a Singaporean’s historic awareness beyond 1819 would have been a misuse of history”. Kwa Chong Guan, ed. S. Rajaratnam on Singapore: From Ideas to Reality (Singapore: World Scientific, 2006), 252. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 327.5957 S) ↩

-

John Miksic and Cheryl-Ann Low Mei Gek, eds., Early Singapore, 1300s–1819: Evidence in Maps, Text, and Artefacts (Singapore: Singapore History Museum, 2004). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.5703 EAR-[HIS]) ↩

-

See, for example, Kwa Chong Guan et al., Seven Hundred Years: A History of Singapore (Singapore: National Library Board and Marshall Cavendish Editions, 2019). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 KWA) ↩

-

Lim, “Geographical Setting,” 3. ↩

-

Sim Meijun Sophie, “Fishing Tales: Singapura Dilanggar Todak as Myth and History in Singapore’s Past” (master’s thesis, National University of Singapore, 2005), 13. ↩

-

Daniel Defoe, A New Voyage Round the World (London: G. Read, 1730); Daniel Defoe, The Life, Adventures, and Pyracies, of the Famous Captain Singleton (London: Printed for J. Brotherton, 1720). For poetry, the most famous is Luís De Camoes, Os Lusíadas [The Lusiads], trans. R. F. Burton, 2 vols. (London: Bernard Quaritch, 1880). Many versions of this poem exist. Other references in poetry can be found in Onno Zwier van Haren, De Geusen [The beggars] (Amsterdam: Adrianus Hupkes, 1772); Lope de Vega, La Circe con otras rimas y prosas [Circe with other lyric poems and prose pieces] (Madrid: En casa de la biuda de Alonso Martin, 1624); and Miguel Botelho de Carvalho, La Filis (Madrid: Por Iuan Sanchez, 1641) ↩

-

For other creative tales of Singapore and the wider region, see Benjamin J. Q. Khoo, “Strange and Alternative Visions of Singapore and the Malay Peninsula,” BiblioAsia 17, no. 3 (Oct–Dec 2021). ↩

-

Some examples include Giovanni Ramusio’s Navigationi et viaggi (1550–59), Richard Hakluyt’s Principall Navigations (1589; 1598), and the collections published by the De Bry family, the Collectiones Peregrinationum, and the Grands Voyages and Petits Voyages. ↩

-

The National Library of Singapore has several pieces of these travel collections, inherited from older acquisitions in its special collections, such as the full set of the second edition published in six volumes. See Awnsham Churchill and John Churchill, A Collection of Voyages and Travels, Some Now First Printed from Original Manuscripts, Others Now First Published in English, 6 vols. (London: J. Walthoe, 1732). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 910.8 CHU) ↩

-

Kwa et al., Seven Hundred Years, 81. ↩

-

Allan Gilbert, “Pierre Davity: His ‘Geography’ and Its Use by Milton,” Geographical Review 7, no. 5 (1919): 334; Pierre du Jarric, Histoire des choses plus memorables advenues tant ez Indes Orientales, etc. [History of the most memorable things that occurred in the East Indies] (Bordeaux: S. Millanges, 1608), 177, 629–30. ↩

-

Andrew Pettegree, “Centre and Periphery in the European Book World,” Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 6, no. 18 (2008): 107–26. See also Andrew Pettegree and Arthur der Weduwen, The Bookshop of the World: Making and Trading Books in the Dutch Golden Age (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019), 266–93. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RBUS 381.45002 PET-[BIZ]) ↩

-

Gerald Maclean, “Early Modern Travel Writing (I): Print and Early Modern European Travel Writing,” in The Cambridge History of Travel Writing, ed. Nandini Das and Tim Youngs (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019), 65. ↩

-

Joao De Barros, Da Asia De Joao De Barros, Dos Feitos, Que Os Portuguezes Fizeram No Descubrimento, E Conquista Dos Mares, E Terras Do Oriente. Decada Primeira, Parte Segunda [Asia of Joao de Barros: The deeds of the Portuguese in the discovery and conquest of the seas and lands of the Orient, first decade, second part] (Lisboa: Na Regia Officina Typografica, 1777), 3 (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 915.4042 BAR); Bras de Albuquerque, Commentarios Do Grande Afonso Dalboquerque, Capitão Gerai Que Foi Das Indias Orientaes Em Tempo Do Muito Poderoso Rey D. Manuel, O Primeiro Deste Nome, Parte III [Commentaries of the Great Afonso Dalboquerque, who was Captain-General of the East Indies in the time of the very powerful King D. Manuel, the first of his name, part three] (Lisboa: Na Regia Officina Typografica, 1774), 85. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 946.902 ALB) ↩

-

Guido Gualtieri, Relationi Della Venuta Degli Ambasciatori Giaponesi a Roma Sino Alla Partita Di Lisbona [Account of the arrival of the Japanese ambassadors in Rome after their arrival in Lisbon] (Roma: Francesco Zannetti, 1586), 32–35. ↩

-

J. J. Sheehan, Seventeenth-Century Visitors to the Malay Peninsula (Singapore: Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1934), 90. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 915.95 SEV-[JSB]) ↩

-

Ignazio Falanga, Storia Degli Ordini Regolari Colla Vita De’loro Fondatori Del P. Flaminio Annibali, Tomo IV [History of the regular orders with the life of their founders by Fr. Flaminio Annibali, vol. 4] (Napoli: Presso Nicola Gervasi, 1796), 338–39. ↩

-

Peter Borschberg, The Memoirs and Memorials of Jacques De Coutre: Security, Trade and Society in 17th- Century Southeast Asia (Singapore: NUS Press, 2014), 97. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959 COU) ↩

-

Perahu, Prau or Proa: A Malay Sailing Boat. ↩

-

Anonymous, Diversi Avisi Particolari dall’Indie Di Portogallo Ricevuti, Dall’anno 1551 Fino Al 1558 Dalli Reverendi Padri Della Compagnia Di Giesu [Various special reports from the Indies of Portugal received from the year 1551 to 1558 by the Reverend Fathers of the Company of Jesus], vol. 1 (Venice: Michele Tramezzino, 1565). The ship belonged to Don Antonio di Norogna, Captain of Melaka, a caravel of the King. ↩

-

Diego De Aduarte, Tomo Primero de la Historia de la Provincia Del Santo Rosario De Filipinas, Iapon Y China, de la Sagrada Orden De Predicadores [First volume of the history of the province of Santo Rosario of the Philippines, Japan and China, of the Sacred Order of Preachers] (Zaragoça: por Domingo Gascon, 1693), 207. ↩

-

Joao Tavares de Vellez Guerreiro, Jornada, Que Antonio De Albuquerque Coelho, Governador, E Capitao General da Cidade Do Nome De Deos De Macao Na China, Fez De Goa Ate Chegar A Dita Cidade No Anno De 1718 [Journey made by Antonio de Albuquerque Coelho, Governor and Captain-General of the city of the name of God of Macau in China, from Goa to said city] (Lisboa: Officina da Musica, 1732), 258. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 327.51032 GUE) For a translated account in English, see Joao Tavares de Vellez Guerreiro, A Portuguese Account of Johore, trans. T. D. Hughes (Singapore: Royal Asiatic Society, 1935). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 959.5103 GUE-[JSB]) ↩

-

De Camoes, Os Lusíadas, vol. 2, 405; Barros, Da Asia, 307. ↩

-

Manuel de Faria y Sousa, The Portuguese Asia, or, The History of the Discovery and Conquest of India by the Portuguese (1695; repr., Farnborough, Hants: Gregg International, 1971), 415–18. (From National Library Singapore, call no. R 946.902 FAR) Pierre Duval was a French geographer and editor of Pyrard’s voyages. See François Pyrard, Voyage De François Pyrard De Laval, ed. Pierre Duval (Paris: Chez Louis Billaine, 1679), 85. For the English version translated from the third French edition of 1619, see François Pyrard, The Voyage of François Pyrard of Laval to the East Indies, the Maldives, the Moluccas, and Brazil, ed. Albert Gray (London: Hakluyt Society, 1887). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 910.8 HAK-[GBH]) ↩

-

Peter Borschberg, The Singapore and Melaka Straits: Violence, Security and Diplomacy in the 17th Century (Singapore: NUS Press, 2010), 17–21. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 911.16472 BOR) ↩

-

Albuquerque, Commentarios Do Grande Afonso Dalboquerque, 99. ↩

-

Thomas Herbert, Some Years Travels into Divers Parts of Africa, and Asia the Great, etc. (London: Printed by R. Everingham, for R. Scot, T. Basset, J. Wright and R. Chiswell, 1677), 356. ↩

-

Barros himself confirmed this: “E segundo os povos Malaios dizem, (de quem nos recebemos esta relaçao)” [And as the Malays say (from whom we received this report)]. Joao de Barros, Da Asia De Joao De Barros, Dos Feitos, Que Os Portuguezes Fizeram No Descubrimento, E Conquista Dos Mares, E Terras Do Oriente. Decada Primeira, Parte Segunda [Asia of Joao de Barros: the deeds of the Portuguese in the discovery and conquest of the seas and lands of the Orient, second decade, second part] (Lisboa: Na Regia Officina Typografica, 1777), 4. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 915.4042 BAR ↩

-

Giuseppe Marcocci, The Globe on Paper: Writing Histories of the World in Renaissance Europe and the Americas (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020), 55–56. Ramusio was an avid collector and compiled his own set of travel writings, including an abridged extract of the Portuguese apothecary Tomé Pires’s Suma Oriental (1512–15), a work not published until 1944. ↩

-

Marcocci, Globe on Paper, 55–56. Barros’s second volume of Decadas, which contains the histories of Singapore and Melaka, was translated into Italian by Alfonso Ulloa in 1562. Joao De Barros, Dell’Asia La Seconda Deca Del S. Giovanni Di Barros [Asia, the second decade of João de Barros] (Venetia: Appreso Vincenzo Valgrisio, 1562). Other snippets of the Singapore story found in Barros’s or Albuquerque’s accounts were cited in the celebrated Cosmographia (1628), attributed to the German geographer Sebastian Münster, bringing knowledge to German readership. ↩

-

Christina Skott, “Imagined Centrality: Sir Stamford Raffles and the Birth of Modern Singapore,” in Singapore from Temasek to the 21st Century: Reinventing the Global City, ed. Karl Hack, Jean-Louis Margolin and Karine Delaye (Singapore: NUS Press, 2010), 158–59. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 SIN) Another circuit of knowledge took it to France and England. The French traveller Vincent le Blanc’s account (1662), for example, mentioned “a certain tyrant who had wanted to seize the state of Singapore […] which was the entry to all the Orient and commanded the whole country”. ↩

-

Sebastian Münster, Cosmographia Oder Beschreibung Der Gantzen Welt etc. [Cosmography or description of the whole world, etc.], facsimile reproduction of the Basel edition of 1628 (Lindau: Antiqua Verlag, 1978), 1590–91. Similarly, the third volume of the English cleric Peter Heylyn’s Cosmographie (1652) contained an account of Parameswara, which also explained how Singapore could be considered as the mother of Melaka. ↩

-

Vincent le Blanc, Le voyageur Curieux Qui Fait Le Tour du Monde, etc. [The curious traveller who goes around the world] (Paris: Chez François Clovsier, 1662), 131–32. These three accounts of the 17th century show how far knowledge originating from Portuguese writings of Singapore and its straits had circulated. ↩

-

Peter Heylyn, Cosmographie. The Third Book, Containing the Chorographie and Historie of the Lesser and Greater Asia, and All the Principal Kingdoms, Provinces, Seas, and Isles Thereof (London: Printed for Henry Seile, 1652), 241–42. ↩

-

For Van der Aa’s collections, see for example Joao De Barros, Ongemeene Scheeps-Togten En Manhafte Krygs-Bedryven Te Water En Te Land Door Diego Lopez De Sequeira, Als Kapitein General En Gouverneur Ter Voortzetting Van Der Portugyzen Gebied En Vryen Koophandel in De Oost-Indien, Met IX Scheepen Derwaarts Gedaan, In ‘T Jaar 1518, etc. [Remarkable naval excursions and military manoeuvres on water and land by Diego Lopez de Sequeira, as Captain General and Governor for the expansion of the Portuguese territory and free trade in the East Indies, with IX ships in the year 1518] (Leiden: Pieter van der Aa, 1707). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 910.41 BAR-[FAN]) João de Barros, Roemwaardige Scheeps-Togten En Dappere Krygs-Bedryven Ter Zee En Te Land, Onder ’T Bestuur Van Don Duarte De Menezes, Als Opperhoofd Van De Vloot En Gouverneur Van Oost-Indien, Ter Aflossing Van Den Heer Generaal Diego Lopez De Sequeira, Met XII Schepen Uit Portugaal Derwaarts Gedaan, in ’T Jaar 1521,etc. [Famous voyages and valiant war-forces at sea and on land, under the leadership of Don Duarte de Menezes, as chief of the fleet and governor of the East Indies, in replacement of the Lord General Diego Lopez de Sequeira, with XII ships from Portugal to the East Indies, in the year 1521, etc.] (Leiden: Pieter van der Aa, 1706). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 954.025 MEN-[KSC]) ↩

-

François Valentijn, Oud En Nieuw Oost-Indiën, Vervattende Een Naaukeurige En Uitvoerige Verhandelingen Van Nederlands Mogentheyd in Die Gewesten, etc. Vde Deel [Old and New East Indies, containing an accurate and compendious treatment of Dutch power in these regions, etc. pt 5] (Dordrecht and Amsterdam: Joannes van Braam and Gerard onder de Linden, 1726), 316. ↩

-

Valentijn, Oud En Nieuwe Oost-Indiën, 318–19. ↩

-

Two such examples of pre-1819 encyclopaedic publications that cite Valentijn are John Pinkerton, Modern Geography, etc. (London: Printed for T. Cadell and W. Davies, etc., 1807), 242–3; and John Wilkes, Encyclopedia Londinensis, etc. [London encyclopaedia], vol. 14 (London: Printed for the Proprietor, etc., 1816), 181–82. For other citations, see Friedrich von Wurmb, Merkwürdigkeiten Aus Ostindien, Die Länder-Volker-Kunde Und Naturgeschichte Betreffend [Curiosities from the East Indies regarding the history of its country, people and nature] (Gotha: Carl Wilhelm Ettinger, 1797), 398–99. ↩

-

Peter Borschberg, “Portuguese, Spanish and Dutch Plans to Construct a Fort in the Straits of Singapore, ca. 1584–1625,” Archipel 65 (2003): 55–88. (From National Library Singapore, call no. R 959.005 A) ↩

-

Peter Borschberg, “The Seizure of the Sta. Catarina Revisited: The Portuguese Empire in Asia, VOC Politics and the Origins of the Dutch-Johor Alliance (1602–c. 1616),” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 33, no. 1 (February 2002): 31–62 (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website); Peter Borschberg, “Security, VOC Penetration and Luso-Spanish Co-operation: The Armada of Philippine Governor Juan de Silva in the Straits of Singapore, 1616,” in Iberians in the Singapore-Melaka Areaand Adjacent Regions (16th to 18th century), ed. Peter Borschberg (Wiesbaden and Lisbon: Harrassowitz and Fundação Oriente, 2004), 35–62. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.50046 IBE) ↩

-

This manuscript is kept in the Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal and is yet to be published. Nevertheless, the sketch helps us to visualise ships gathering off Singapore. It can be accessed at https://purl.pt/1275. ↩

-

Jacht: Dutch light-sailing vessel. ↩

-

Robert Parthesius, Dutch Ships in Tropical Waters: The Development of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) Shipping Network in Asia, 1595–1660 (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2010), 154–56. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEAS 387.509598 PAR) ↩

-

Antonio Franco, Imagem da Virtude Em O Noviciado da Companhia De Jesus No Real Collegio De Jesus De Coimbra Em Portugal, etc. [Image of virtue in the novitiate of the Society of Jesus in the Real Collegio de Jesus de Coimbra in Portugal, etc.] (Lisboa: Na Officina Real Deslandesiana, 1714), 275–76. ↩

-

Daniello Bartoli, Compendio Della Vita, E Morte Del P. Marcello Mastrilli Della Compagnia Di Giesu, etc. [Compendium of the life, and death of Fr. Marcello Mastrilli of the Company of Jesus, etc.] (Napoli: Luc’Antonio di Fusco, 1671), 86. ↩

-

Carvalho, La Filis, 47. ↩

-

Jean Chardin, Voyages De Monsieur Le Chevalier, En Perse, Et Autre Lieux De L’Orient. Tome Dixieme [Travels of Sir Chevalier into Persia, and other places of the Orient] (Amsterdam: Jean Louis de Lorme, 1711), 129. ↩

-

Antonio José Alvarez de Abreu, Extracto Historial Del Expediente Que Pende En El Consejo Real, Y Supremo De Las Indias, a Instancia de la Ciudad De Manila, Y Demas De Las Islas Philipinas [Historical extract of the record pending in the Royal and Supreme Council of the Indies, at the request of the city of Manila, and others of the Philippine Islands] (Madrid: Juan de Ariztia, 1736), 8. ↩

-

There is room to debate what is considered “substantial” and deserving of national interest and inclusion. ↩

-

Terence Chong, “The Bicentennial Commemoration: Imagining and Re-imagining Singapore’s History,” Southeast Asian Affairs (2020): 330–31. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959 SAA) ↩

-

Kwa et al., Seven Hundred Years, 8–11; Karl Hack and Jean-Louis Margolin, “Singapore: Reinventing the Global City,” in Singapore from Temasek to the 21st Century: Reinventing the Global City, ed. Karl Hack, Jean-Louis Margolin and Karine Delaye (Singapore: NUS Press, 2010), 4. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 SIN) ↩

-

Geoffrey Gunn, Overcoming Ptolemy: The Revelation of an Asian World Region (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2018), 191. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEAS 912.509 GUN) ↩

-

Isaac Commelin, Begin Ende Voortgangh Van De Vereenighde Nederlantsche Geoctroyeerde Oost-Indische Compagnie, etc., vol. 2 [Origin and progress of the Dutch East India Company] (Amsterdam: n.p., 1646), 21, 36, 38. (From National Library Online; call no. RRARE 910.9492 BEG) ↩

-

Adrien Delmas, “Writing History in the Age of Discovery, According to La Popelinière, 16th–17th centuries,” in The Dutch Trading Companies as Knowledge Networks, ed. Siegfried Huigen, Jan L. de Jong and Elmer Kolfin (Leiden: Brill, 2010), 301–4. (From National Library Singapore, call no. R 306.4 DUT) ↩

-

For a carefully researched study, see Richard Yeo, Encyclopaedic Visions: Scientific Dictionaries and Enlightenment Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001). (From National Library Singapore, call no. R 032.09033 YEO) ↩

-

Anonymous, Encyclopedia Perthensis, etc., 2nd ed., vol. 21 (Edinburgh: John Brown, etc., 1816), 3. ↩

-

Selvaraj Velayutham, Responding to Globalization: National, Culture and Identity in Singapore (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2007), 21–25. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 305.80095957 VEL-[LKY]) ↩

-

Fabio López Lázaro, The Misfortunes of Alonso Ramirez: The True Adventures of a Spanish American with 17th-century Pirates (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2011), 26–34, 121 Retrieved from OverDrive. (myLibrary ID is required to access this ebook); William Dampier, Dampier’s Voyages: Consisting of a New Voyage Round the World […], ed. John Masefield (London: E Grant Richards, 1906), 559. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 910.41 DAM-[GBH]) ↩

-

For an overview, see Peter Borschberg, “European Records for the History of Singapore before 1819,” in An Old New World: From the East Indies to the Founding of Singapore, 1600s–1819, ed. Stephanie Yeo (Singapore: National Museum of Singapore, 2019), 6–18. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 NAT-[HIS]) ↩

-

Barros, Ongemeene scheeps-togten, 145–52. Ujantana is a corruption of “Ujong Tanah” and refers to the southern half of the Malay Peninsula, including Singapore. ↩

-

Julia Schleck, “Forming Knowledge: Natural Philosophy and English Travel Writing,” in Travel Narratives, the New Science, and Literary Discourse, 1569–1750, ed. Judy A. Hayden (New York: Routledge, 2012), 57; Debbie Lisle, The Global Politics of Contemporary Travel Writing (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 11. ↩

-

This partial study is only confined to references in European literature. Peter Preston, Singapore in the Global System: Relationship, Structure and Change (New York: Routledge, 2012), 1–2. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 306.095957 PRE) ↩