Bacalah Singapura: Reading Habits in Singapore (1960s–1990s)

Reading surveys in the nation-building years reveal what Singaporeans read and why it mattered.

By Janice Loo

In June 2025, the National Library Board released the results of the 2024 National Reading Habits Study which found that 89 percent of Singapore adults read more than once a week. News (76 percent) and online articles (65 percent) were the most popular reading materials, surpassing books (28 percent), magazines (16 percent) and reports (12 percent). While respondents acknowledged the benefits of reading, most said that they tended to spend more time on other activities (62 percent) or get bored after reading for a while (38 percent).1

This challenge of cultivating a reading habit is not a new one, as seen in studies from the 1960s through to the 1990s on reading levels in Singapore. Given that reading is crucial to learning, access to information, as well as social and economic participation, reading habits – how often people read, what they read and in which languages – go beyond personal leisure choices and have been seen as matters of national consequence.

Education, Bilingualism and Children’s Reading Habits

Singapore gained independence amidst much uncertainty on 9 August 1965. The 1960s and 1970s were a “survival-driven” phase as the government focused on creating a literate and skilled workforce to support rapid industrialisation and secure the future of the fledgling nation. Mathematics, science and technical subjects were emphasised to prepare youth for employment and continuous upskilling.2 At the same time, bilingual education in English and a mother tongue – Malay, Mandarin or Tamil – was implemented.3 While English was necessary for business and for acquiring technical knowledge (where literature in vernacular languages was scarce), mother tongue languages were deemed essential for the preservation of cultural values and traditions, and were used for civic education.4

This educational landscape formed the backdrop for the dozen reading surveys conducted in the 1960s and 1970s – largely by education researchers – to examine the reading habits and preferences of primary and secondary school students.5

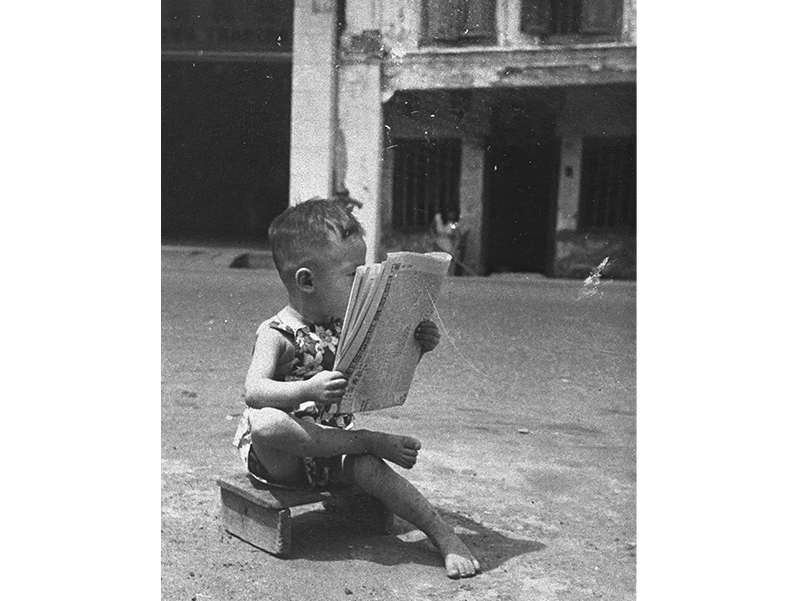

The earliest such study was initiated in 1966 by the Research Unit of the Teachers’ Training College (TTC), which surveyed over 1,500 primary school pupils from the English, Chinese and Malay language streams. It aimed to provide insights to parents, teachers, librarians and education authorities in supporting children’s reading development.6

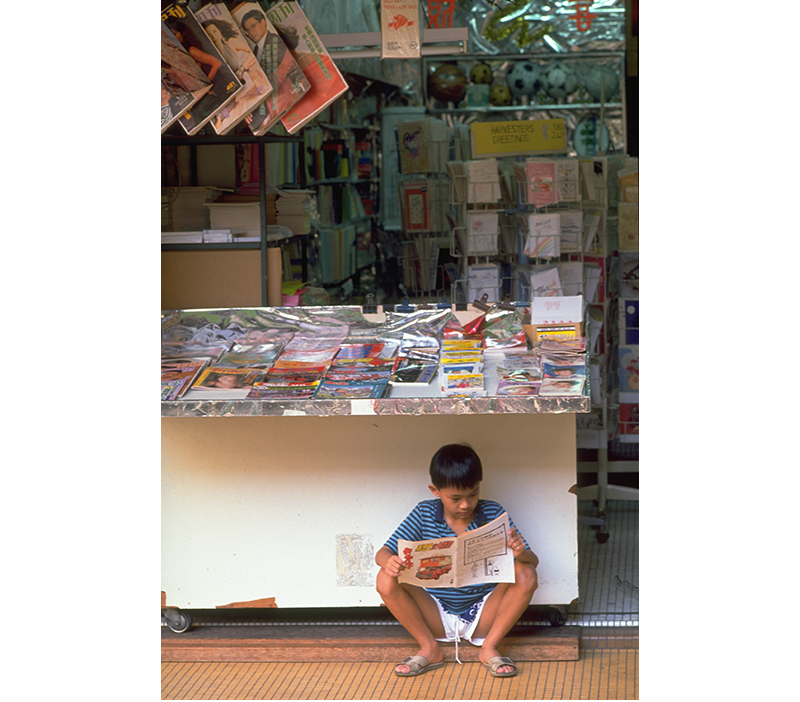

This study found that newspapers were the most popular reading material, followed by comics and magazines.7 It also revealed low levels of reading in a second language, which was highlighted as a “grave concern” given the importance of bilingualism. Additionally, students showed a preference for fiction over nonfiction, with classroom and school libraries serving as their primary sources of reading material due to convenient access.8

However, there were limitations with the survey’s research design. One reviewer noted that the method of administering formal questionnaires in a school setting likely skewed the results, with children giving socially desirable responses rather than their genuine preferences.9 The questionable validity of responses was apparent in two survey items: one where a high proportion – almost 60 percent – of children claimed to prefer reading over TV, and another where a significant number improbably indicated they would rather spend their pocket money on books over toys, sweets or cinema tickets.10

The report’s compilers themselves acknowledged that such positive responses were likely influenced by the classroom environment and the teacher’s presence.11 Despite its shortcomings, the TTC study was a commendable first step in sketching a complex subject and underscored the need for more research.

Further surveys in the late 1970s, conducted mostly by staff and students at the Institute of Education (IE), were spurred by problems besetting the education system: high failure and attrition rates, low literacy levels and ineffective bilingualism.12 One underlying cause, as identified in a landmark 1978 education review, was that 85 percent of schoolchildren did not speak the languages of instruction (primarily English and Mandarin) at home, which hampered learning both in and outside of the classroom.13

A 1978 survey by IE revealed poor levels of reading, especially in second languages among Primary Six pupils.14 This was troubling as the primary school years are a critical period for developing lifelong reading habits.15 Dismayed by the findings, Education Minister Chua Sian Chin stressed the importance of reading to national goals at the 1978 Festival of Books and Book Fair: “We will not be able to succeed in our effort of improving language learning and attain our objective of bilingualism unless we get more and more pupils to read books and magazines in their first and second languages.”16

The IE survey approached reading as a socially embedded activity shaped by parents, teachers and peers. While newspapers were present in 89 percent of households and read by 64 percent of parents, book reading was markedly rare, with only 2 percent of parents reading books and a mere 10 percent encouraging their children to do so.17 It was thus little wonder that children tended to gravitate towards newspaper reading rather than books. The majority of parents in the sample were Chinese-speaking, blue-collar workers, whose children consistently reported having the fewest comics, books and magazines at home. This underscored the impact of socioeconomic status on both access to varied reading materials and the development of reading habits.18

Concluding that little could be done about the home environment, the IE report focused on the role of schools. It emphasised that teachers needed to be readers themselves to effectively model reading habits, and recommended incorporating regular reading and book-related activities, like story dramatisations, into lessons.19

The IE survey also raised concerns about the time children spent watching television at the expense of reading, with 62 percent watching one to three hours daily and 21 percent exceeding three hours. Television emerged as the greatest competitor to reading because it functioned as a shared family activity that naturally drew children in and, unlike reading, could be enjoyed with little linguistic competence.20

Adult Readers, Lifelong Workers

While research into children’s reading habits began shortly after independence, it was only in 1980 that the first national survey of adult reading habits was conducted.21

In 1975, S. Gopinathan, chairman of the National Book Development Council of Singapore (now the Singapore Book Council),22 highlighted the dearth of data on what Singaporeans read. He noted: “We know we have certain advantages; very high per capita income, easy distribution because we are geographically small, literacy rates are very high. In theory, these should lead to a certain level of reading, and not only of textbooks. But there is no real documentation on what people in fact read.”23

Consequently, the council commissioned the first National Readership Survey in 1980, aiming to gather data on adult reading habits, book-buying behaviour and library usage. It sampled around 2,000 non-schooling Singaporeans aged 15 to 49 from about 800 households.24

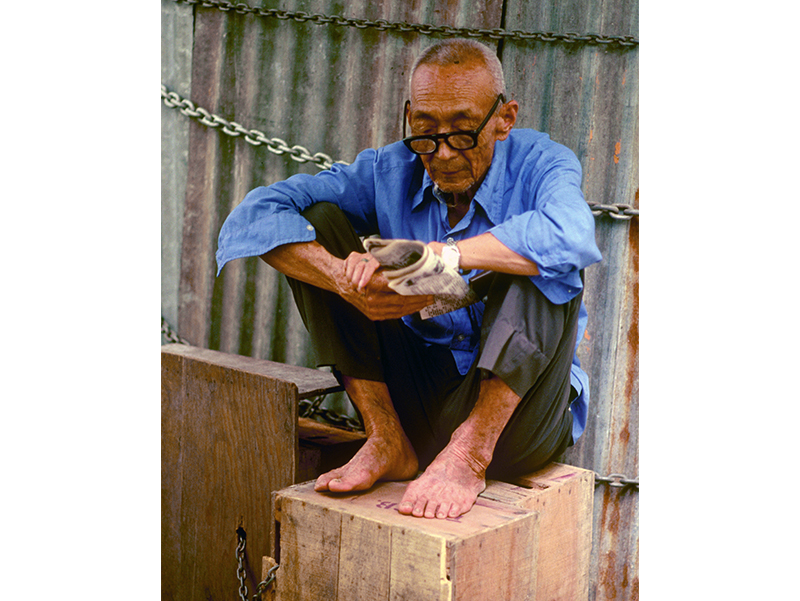

The results, published in 1981, came as no surprise. Television dominated leisure time (48.3 percent), followed by music (15 percent) and then reading (13.1 percent). While over 90 percent of respondents engaged in some form of reading weekly (with only 2.7 percent reporting no reading at all), this had to be balanced against the finding that 37.9 percent did not read books and 33.7 percent spent less than three hours weekly on them. In contrast, newspapers were widely read, with only 2.4 percent non-readers and 39.6 percent dedicating three to five hours weekly to them.25

The survey also found that a mere 16.1 percent of respondents were members of the National Library.26 Most people obtained books and magazines by borrowing from friends and relatives, or purchasing them from bookshops rather than using the public libraries.27

The findings highlighted socioeconomic correlations with reading habits. Heavy readers (those who read more than six hours weekly) tended to have higher levels of education, worked in the professional, administrative and clerical occupations, and earned higher incomes. Conversely, non-readers generally lacked formal education or did not complete primary education, worked in production or service roles, and had lower incomes.28

As Singapore shifted towards capital-intensive, high-technology industries in the early 1980s, national survival again hinged on the power of reading, as Minister for Communications Yeo Ning Hong emphasised at the 1984 National Reading Month launch: “In order to keep pace and not be left behind in the backwaters, Singaporeans must therefore be agile and adapt to the rapid changes that we now see taking place in many industrialised countries… The ability to read will provide us with the key to upgrading ourselves… The person who stops reading upon leaving school or university increases his own chance of stagnation and irrelevance in future economic developments.”29

A Cultured People

In the mid-1980s, the government launched a new vision for Singapore to become a “Nation of Excellence”. This would encompass the development of a cultivated society that First Deputy Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong described as “a society of well-read, well-informed citizens, a refined and gracious people, a thoughtful people, a society of sparkling ideas, a place where art, literature and music flourish” and “not a materialistic, consumeristic society where wealth is flaunted and money spent thoughtlessly”.30

Aside from the intrinsic value of arts and culture, the government saw its economic potential as a new growth sector following the 1985 recession.31 To that end, the Advisory Council on Culture and the Arts (ACCA) was established in 1988 to develop a long-term plan for arts and cultural development in Singapore. The Committee on Literary Arts was formed to assist the ACCA, and recognising the importance of reading, a Sub-Committee on Reading was created to assess the reading habit in Singapore and make recommendations for its promotion.32

Drawing on the 1980 and 1988 national reading surveys,33 as well as the 1987 National Survey on Arts and Culture, the Sub-Committee on Reading found that despite a high literacy rate of 94 percent in 1988, Singaporeans read a limited range of subjects, preferring popular fiction, followed by cookery and hobby books, while literary works and drama ranked last.34 On the bright side, more were reading for pleasure as well as for information and knowledge.35 Although the steady growth in library membership was another encouraging sign, the sub-committee noted that existing library services struggled to keep up with public demand.36

The sub-committee identified several crisis areas, chiefly the utilitarian view of reading as a means for academic or career advancement. Once again, the same issue was brought up: developing young readers required the involvement of both parents and teachers.

Recognising that building a reading culture required community-wide efforts, recommendations included training for parents and teachers, creating reading corners in housing estates, enhanced resourcing of libraries and the book council, as well as partnerships with media, publishers and bookshops.37

A Developed (Reading) Nation

In 1993, the National Library commissioned a survey which sampled some 2,000 respondents aged 13 to 69 from 1,000 households. The survey painted a mixed picture: while a small but growing segment of Singaporeans had developed a passion for reading, an increasing number of literate individuals had disengaged from books.38 The percentage of literate persons who had read a book in the last 12 months had dropped to 50 percent from 57 percent in 1980. However, among readers, those spending three to nine hours weekly increased from 41 percent to 65 percent, and those reading 10 hours or more rose from 6 percent to 19 percent.39

Three years later, in 1996, Deputy Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong highlighted that while the number of computers per capita was often used to measure development, another equally important indicator to pay attention to was the number of books that the average person reads per year. He noted that the 1993 National Reading Survey reported that Singaporeans read 8.3 books annually, significantly behind Japan’s 18 books and America’s 25 books per person. “Becoming a developed country,” Lee said, “means balancing economic growth with cultural and social achievements.” He observed that “Singapore has some distance to go to catch up”.40

The 1993 National Reading Survey coincided with the report by the Library 2000 Review Committee in 1994. The committee had been convened in 1992 to map out the transformation of library services to enhance Singapore’s learning capacity and competitive edge. Among its key recommendations were establishing the National Library Board as a new statutory board and creating a tiered library network to serve diverse information needs as the country positioned itself to become a knowledge-based economy in the new millennium.41

Read On, Singapore

Since independence, nurturing the habit of reading has been viewed as a national priority, one whose goals have evolved in tandem with Singapore’s development – from being vital to national survival in the 1960s and 1970s to enabling first-world aspirations in the 1980s and 1990s. Reading ability undergirded the ideal of the Singapore citizen-worker: a highly educated individual, fluent in both English and their mother tongue, who embraces lifelong learning to seize opportunities in a fast-changing global economy. Reading surveys played a crucial role in this journey, quantifying habits and highlighting concerns that mobilised multiple stakeholders in building a reading culture.

Today, reading competes with a dizzying array of digital distractions. However, its fundamental importance endures. As reading advocate and library pioneer Hedwig Anuar observed: “The death of reading has been forecast many a time with the advent of radio, television and the computer. But regardless of the newer forms of media, the future knowledge society or information society will ultimately depend on the ability to read, and to read with intelligence and discrimination.”42 Her remarks, written over 30 years ago, still resonate today.

Janice Loo is a Senior Librarian with the National Library Singapore. Her responsibilities include collection management and content development as well as research and reference assistance on topics relating to Singapore and Southeast Asia.

Janice Loo is a Senior Librarian with the National Library Singapore. Her responsibilities include collection management and content development as well as research and reference assistance on topics relating to Singapore and Southeast Asia.Notes

-

“2024 National Reading Habits Study on Adults,” 14, 16, 64–65, 68, National Library Board Singapore, http://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/-/media/NLBMedia/Documents/About-Us/Press-Room-Publication/Research-and-Studies/NRHS-2024-Adults-20250619_full-report_for_publication.pdf. ↩

-

Goh Chor Boon and S. Gopinathan, “The Development of Education in Singapore Since 1965,” in Toward a Better Future: Education and Training for Economic Development in Singapore Since 1965, ed. Lee Sing Kiong et al. (Washington, DC: The World Bank, 2008), 13, 15, 18–19. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 370.9595709045 TOW); Ho Wing Meng, “Education for Living or Singapore’s Answer to the Problem of Technological Development Versus Cultural Heritage,” in Cultural Heritage Versus Technological Development: Challenges to Education (Hong Kong: Maruzen Asia, 1981), 140. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 370 CUL) ↩

-

By 1966, learning a second language was made mandatory in primary and secondary schools, and by 1969, it became an examinable subject. ↩

-

Lee Kok Cheong, “The Use of the English Language in Education in Singapore (With Special Reference to Science and Technology),” in Cultural Heritage Versus Technological Development: Challenges to Education, ed. Rolf E. Vente, R.S. Bhathal and Rukhyabai M. Nakhooda (Hong Kong: Maruzen Asia, 1981), 157. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 370 CUL); Goh and Gopinathan, “The Development of Education in Singapore Since 1965,” 14–15; Nirmala Purushotam, Negotiating Multiculturalism: Disciplining Difference in Singapore (Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2000), 67. (From National Library Singapore, call no.: RSING 306.44095957 PUR); Chia Yeow Tong, Education, Culture and the Singapore Developmental State: “World-Soul” Lost and Regained? (Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire; New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), 45. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 379.5957 CHI) ↩

-

According to Lau Wai Har, there were five major studies on primary school pupils’ reading habits, five for secondary school pupils, one for tertiary students and one for non-schooling adults. See Lau Wai Har, “Reading Research in Singapore: Trends & Prospects,” in The Reading Habit: Regional Seminar on the Promotion of the Reading Habit, Singapore, 7 to 10 September 1981 (Singapore: National Book Development Council of Singapore, 1983), 22–31. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING q028.9 REG-[LIB]) ↩

-

Teachers’ Training College, Reading Interests (Singapore: The College, 1970), 1. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 028.9095957 TEA) ↩

-

Teachers’ Training College, Reading Interests, 64. The compilers acknowledged that the popularity of newspaper reading among children should not be construed as an interest in current affairs, as “reading” in this case likely amounted to no more than a quick glance at the comics, sports and entertainment sections. See Teachers’ Training College, Reading Interests, 16. ↩

-

Teachers’ Training College, Reading Interests, 63–64. At the time of the survey, public library services centred on the National Library on Stamford Road, complemented by part-time branches in Joo Chiat and Siglap, as well as a mobile library service that visited the Tanjong Pagar, West Coast, Nee Soon and Bukit Panjang community centres weekly. This limited reach, coupled with the relative inaccessibility of the National Library to those residing outside of the city, led to class and school libraries being more popular among young readers. ↩

-

V. Perambulavil, “A Survey of Children’s Reading; a Review Article,” Singapore Book World 2, no. 1 (June 1971): 5–6. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 070.5095957 SBW). V. Perambulavil was the coordinator of children’s services at the National Library. Her review was adapted and published as “Once Upon a Time…,” New Nation, 9 October 1971, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Would rather read a book than watch television: 59.8 percent (English medium); 59.6 percent (Chinese medium); Preferred buying books to toys, sweets, or going to cinema: 66.4 percent (Malay medium), 58.8 percent (Chinese medium), 46.6 percent (English medium). See Teachers’ Training College, Reading Interests, 22–24, 35, 54, 65. ↩

-

The report mentioned of a “likelihood that the children might have been trying to please or impress their teachers by pretending a preference for books”. See Teachers’ Training College, Reading Interests, 24, 65. ↩

-

The Teachers’ Training College was restructured into the Institute of Education in 1973. Lau, “Reading Research in Singapore,” 22–25; Goh Keng Swee and Education Study Team, Report on the Ministry of Education 1978 (Singapore: Singapore National Printers, 1979), 4-1. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 370.95957 SIN) ↩

-

Goh and Education Study Team, Report on the Ministry of Education 1978, 1-1, 4-4. In August 1978, Deputy Prime Minister Goh Keng Swee was tasked to lead a study team to identify problems in Singapore’s education system and propose solutions. The Report on the Ministry of Education 1978 (also known as the Goh Report) gave rise to a system of ability-driven education based on streaming known as the New Education System. ↩

-

The survey revealed that 33 percent of the Primary Six students sampled did not read any English books and 41 percent read only one to two books in the previous month. Even lighter reading materials like magazines and comics fared no better. Among those who took Chinese as a second language, 43 percent read no books, 39 percent no magazines, and 66 percent no comics. The situation was worst among those taking English as a second language with 67 percent reading no books, 81 percent no magazines and 81 percent no comics. See Institute of Education, A Measure of Reading: IE Survey of Reading Interests and Habits (Singapore: Institute of Education, 1978), 15–20, 48. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 028.9095957 INS-[LIB]) ↩

-

Institute of Education, A Measure of Reading, Foreword. ↩

-

Chua Sian Chin, “The Opening of the 10th Annual Festival of Books and Book Fair,” speech, Hyatt Hotel Singapore, 26 August 1978, transcript, Ministry of Culture. (From National Archives of Singapore, document no. csc19780826s) ↩

-

Institute of Education, A Measure of Reading, 16, 20, 34–35, 48. ↩

-

Institute of Education, A Measure of Reading, 14, 42–43, 51; “Majority of Poor Pupils Read Only in One Language,” Straits Times, 22 April 1978, 7 (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Institute of Education, A Measure of Reading, 52–53. ↩

-

Institute of Education, A Measure of Reading, 36, 50; “Up to Three Hours a Day Before the Box,” Straits Times, 26 April 1978, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lau, “Reading Research in Singapore,” 25. ↩

-

The council was inaugurated on 13 February 1969. The idea for such an organisation was first proposed in November 1966 at a workshop on the problems of book production and distribution organised by the Library Association of Singapore. The formation of national book development councils to promote reading and development of the local book industry was encouraged by UNESCO to overcome the acute shortage of books in developing countries. See Hedwig Anuar, “Twenty-five Years of Book Development,” Singapore Book World 23 (1993/1994): 1–8. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 070.5095957 SBW) ↩

-

Lu Lin Reutens, “Reading Habits of Singaporeans…,” New Nation, 19 August 1975, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

National Book Development Council of Singapore, First National Readership Survey (Singapore: National Book Development Council of Singapore, 1981), v, xvii, 2, 4. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 028.9095957 FIR-[LIB]); “Council Survey on the S’pore Reader,” Straits Times, 13 April 1980, 11. (From NewspaperSG). ↩

-

Gretchen Mahbubani, “Few Big Surprises,” Straits Times, 25 July 1981, 14. (From NewspaperSG); National Book Development Council of Singapore, First National Readership Survey, 6, 9. ↩

-

The proportion corresponded to some extent with the National Library’s membership figures, which stood at 349,824 members by the end of FY1979, representing 14.8 percent of the population with children forming the largest group. See National Book Development Council, First National Reading Survey, 51; National Library Singapore, National Library Report for the Period April 1979–March 1980 (Singapore: National Library, 1980), 10, 34. (From National Library Online) ↩

-

National Book Development Council of Singapore, First National Reading Survey, 28. ↩

-

National Book Development Council of Singapore, First National Readership Survey, 10–11. ↩

-

Yeo Ning Hong, “The Launching of the Second National Reading Month,” speech, DBS Auditorium, 17 August 1984, transcript, Ministry of Culture. (From National Archives of Singapore, document no. ynh19840817s) ↩

-

“The Strategy for a Nation of Excellence,” Straits Times, 2 December 1986, 26. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Audrey Wong, “The Report of the Advisory Council on Culture and the Arts,” in The State and the Arts in Singapore, ed. Terence Chong (Singapore: World Scientific Publishing, 2019), 111–112. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 700.959570904 STA) ↩

-

Committee on Literary Arts, Report of the Committee on Literary Arts (Singapore: Committee on Literary Arts, 1988), i. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING S820 SIN) ↩

-

The 1980 and 1988 surveys had different sample populations. While the 1980 survey sampled 2,000 non-schooling respondents aged 15 to 49, the 1988 survey covered 1,000 respondents aged 12 and above, which included students. ↩

-

Committee on Literary Arts, Report of the Committee on Literary Arts, 25–26. ↩

-

In 1980, the main reasons for reading were general information (mentioned by 67.8 percent of respondents), pleasure (61 percent) and passing time (53.1 percent). By 1988, pleasure became the leading motivation (67 percent), followed closely by self-improvement (65 percent), passing time (64 percent) and increasing general knowledge (63 percent). The most dramatic change was in reading for information on a particular subject, which quadrupled from 11 percent in 1981 to 46 percent in 1988. See Committee on Literary Arts, Report of the Committee on Literary Arts, 27; Hedwig Anuar, “The Reading Habits of Singaporeans”, The Mirror: A Weekly Almanac of Current Affairs 25, no. 19, (1 October 1989), 12. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 320.9595 MM) ↩

-

Committee on Literary Arts, Report of the Committee on Literary Arts, 27. By the end of FY1987, library membership reached 871,537 or 33 percent of the population, with adults forming the largest group. The significant increase occurred in tandem with the decentralisation of library services in the 1980s. Between the 1980 and 1988 surveys, the library network expanded with five new fulltime branches established in satellite towns outside of the city centre. This expansion, which increased the total number of fulltime branch libraries from three to eight, brought library services within easier reach of Singaporeans. See National Library Singapore, National Library Report for the Period April 1987–March 1988 (Singapore: National Library, 1980), 6. (From National Library Online) ↩

-

Committee on Literary Arts, Report of the Committee on Literary Arts, 25, 31–34, 38–50. ↩

-

Ngian Lek Choh, “Singaporeans, Their Reading Habits and Interests,” Singapore Libraries 24, (1995): 4–5, 8, 12; “Fewer Read, But Those Who Do, Read More,” Straits Times, 18 May 1994, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Ngian, “Singaporeans, Their Reading Habits and Interests,” 4–5. ↩

-

Lee Hsien Loong, “The Opening of the World Book Fair 1996,” speech, World Trade Centre, 24 May 1996, transcript, Ministry of Information and the Arts (1985–1990). (From National Archives of Singapore, document no. lhl19960524s) ↩

-

“Future of Public Library Services to Be Reviewed,” Straits Times, 23 June 1992, 26. (From NewspaperSG); Library 2000 Review Committee, Singapore, Library 2000: Investing in a Learning Nation: Report of the Library 2000 Review Committee (Singapore: SNP Publishers, 1994), 3, 5–14. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 027.05957 SIN) ↩

-

Anuar, “Twenty-five Years of Book Development,” 7. ↩