Excavating the Past

Writing a memoir involves personal experiences, digging deep into our memories and the emphasis on factual information.

By Meira Chand

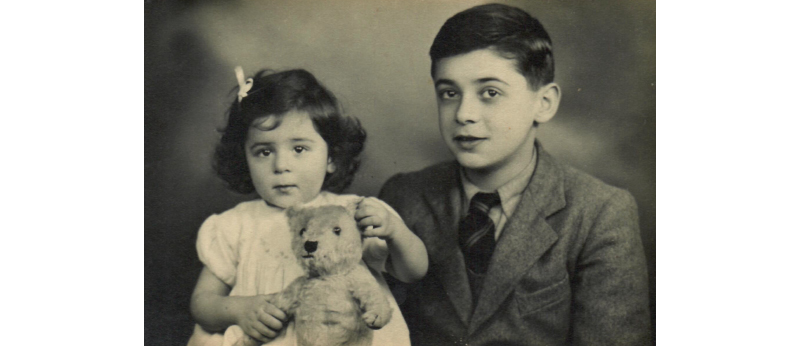

Many people assume that a memoir is the same as a biography or an autobiography, but it is a category of writing entirely on its own. I might not have given much thought to the uniqueness of memoir as a genre, if it were not for my elder brother Roy’s insistence that I write about our father’s extraordinary life.

Our father, Dr Harbans Lal Gulati, went from India to London for medical studies in 1919, at the height of the colonial era. Already a qualified doctor in the British Army in India, he had been posted to the Khyber Pass, had been taken hostage by Afghan tribes and had also witnessed the Amritsar Massacre. In England, despite the formidable discrimination prevalent in that era, he requalified and established himself as a doctor, became a pioneering force in the early National Health Service (NHS) and even stood for parliament in the United Kingdom.

Roy wanted a full-scale biography but I felt it would be a difficult undertaking as so much of our father’s early life was irretrievably lost to time. It was only at Roy’s continued insistence that I reluctantly decided to consider writing a memoir. Unlike a biography or an autobiography, which takes in the entire chronological sweep of a life, a memoir is limited in its scope and supportive of whimsy. It focuses on a reduced canvas of emotional depth, examining from the author’s point of view a particular period, person or event, experiences or themes. Rather like an archaeologist, the memoirist is expected to excavate specific recollections and reveal the hidden truth of what they find. Penning a memoir appeared a more achievable project than a full-blown biography, but I had not attempted the genre before and was wary of the perils awaiting me.

I am by trade a writer of fiction; my work depends on imaginative flights of fantasy. Memoirs have to do with personal experience and are corseted by truth and dependent on fact. However, I was beginning to see the venture as a legacy-type project that would give my children and grandchildren a better sense of who they are. The lives of ancestors, whether recently departed or distantly dead, are shadows stretching away around a family tree, shaping its outline, giving substance and inspiration to future generations. I am always telling people: if you do not write it down, it is gone and lost to history. Now, it seems, I would have to practise what I preached.

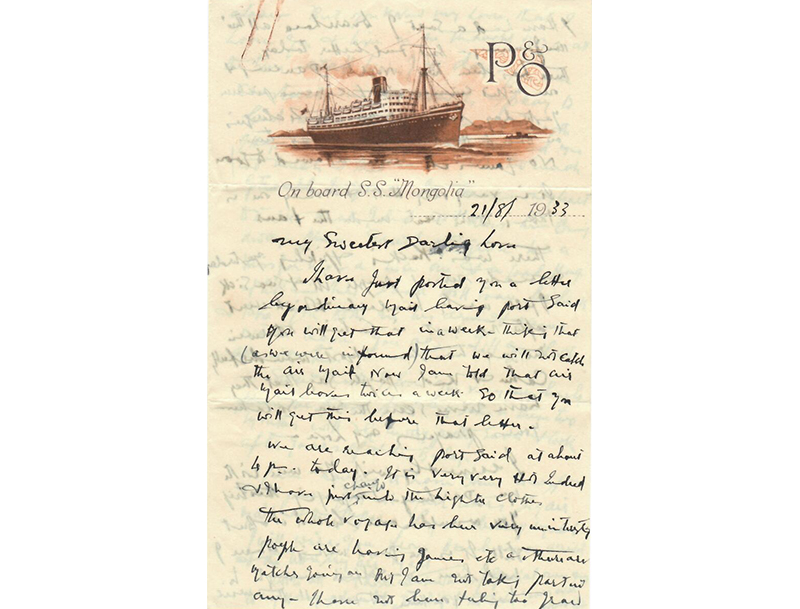

I thought the project would unfold without too much difficulty as I dug into memories and assembled assorted memorabilia. Instead, I quickly found that remembering incidents and assembling old photographs, letters and documents into some kind of chronological order was very different from putting down a corresponding connecting narrative in a coherent and interesting form on paper. In my novel writing life, the only way I knew of making sense of disparate scraps of knowledge and the half-formed ghostly images blowing through my mind was in the form of a story.

I was, however, quickly beginning to realise that a memoir was as much a piece of imaginative narrative as was any novel. The only clear difference seemed to be that with memoirs, unlike fiction, things could not be blatantly made up. I could not build fictional bridges to reach a solid edifice as I could in both fiction and historical fiction. When writing historical fiction, facts are inviolable and cannot be tampered with, but unending fictional licence is given to all that lies between. This is not the case with memoirs where the truth of every word is dauntingly important.

In her book, Still Writing, author Dani Shapiro explains, “It’s a supreme act of control to understand a life as a story that resonates with others… It’s taking this chaos and making a story out of it, attempting to make art out of it… It’s like stitching together a quilt, creating order that isn’t chronological order – it’s emotional, psychological order.”1

As soon as I sat down to begin the memoir, I encountered my first hurdles. The twin issues of time and memory stood before me like a closed gate. My parents had died many decades ago. My younger brother and I were born late in their marriage, a second pair of four children. Of my two much older siblings, who might have memories to share, one had died as a child and the other is now struggling to remember things. By the time my younger brother and I were born, our father was deeply involved in his medical career and a secondary life in politics. He had left the Conservative Party after the war because they did not support the creation of the NHS – which he passionately believed in – and joined the Labour Party which later, when in power, established the NHS. As a member of the Labour Party, he stood unsuccessfully for parliament in 1960, losing by only a handful of votes. He was a somewhat distant figure, always busy with work, and never spoke about his early personal history, or the country of his birth, India. Like most children, I never thought to ask my parents about their lives and they, like most parents, did not think to tell me much about their backgrounds.

I knew a few broad outlines. My father left India for London after the First World War, had met and married my mother, and had never returned to his country. I knew that my mother, Norah Louise Knobel, was Swiss but grew up in England and she was 14 years younger than my father. When I sat down to write, I realised not only how much I did not know about my parents, but that apart from my elderly brother with his fading memory, there was nobody left alive to fill in the gaps. The mists of time had swallowed everything, and I needed to begin my work.

I had encountered the problem of time before in my writing life, particularly while writing historical fiction. In that genre, I had found it possible to successfully overcome the challenge of all that was missing through archival research, and the binding gel of imagination. With enough digging around in the archives, evidence could usually be found to fill most gaps and where the gaps were too large, fiction bridged the void.

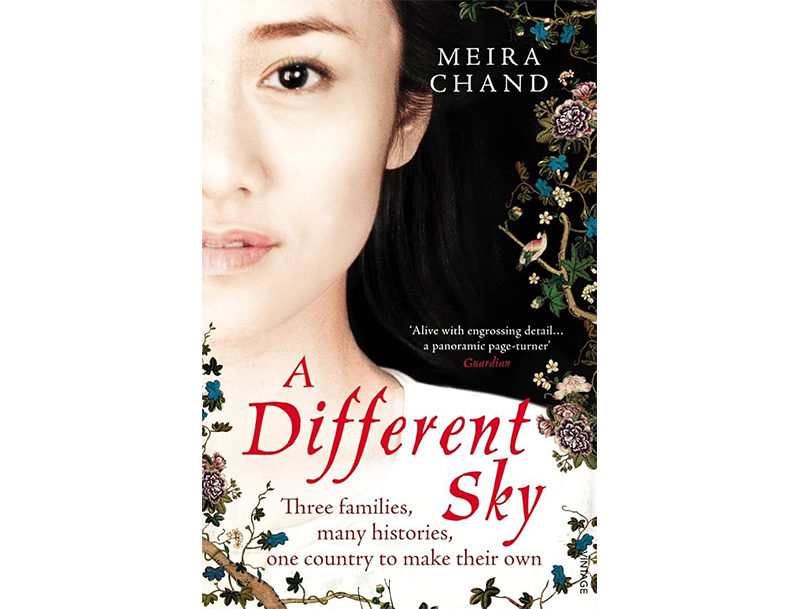

A good example of this is the research I did for my novel A Different Sky (2010), a story set in pre-independence Singapore, an era I knew little about, not having grown up here. The Oral History Centre at the National Archives of Singapore became for me a treasure trove of borrowed memories. I could put on headphones and be immediately surrounded by the recorded voices of numerous people of a bygone time, telling me the details of their lives. In their own voices, a legion of persons no longer living were able to recreate for me the nation’s short but traumatic history.2

Old newspapers in NewspaperSG and the treasure trove of archival photographs and rare books held by the National Library Singapore gave me added contextual information about time, place and events. Through the laborious process of research, I realised I was building a scant Singapore memory of my own upon the wealth of other people’s memories. The process took time, for the learnings and experiences obtained through research had to be absorbed and fully digested before they could, in some strange way, become my own limited memory for me to write successfully.

No such help was available for the personal histories of my parents. I was left with my own and my brother’s meagre store of hazy memories as well as a small stash of letters, documents, photographs and diaries. Yet, as I struggled to begin my memoir, two incidents, one from my own life, and the other the experience of the writer Oliver Sacks – and both coincidentally to do with bombs – revealed to me not only the plasticity of memory, as I had learned through my absorption of the memories of others at the Oral History Centre, but also about its utter untrustworthiness.

I was born in an air-raid during the Second World War in London, and my early years were shaped by the trauma of those chilling times. In the garden of our home, my father had installed an Anderson shelter into which we ran when the shriek of sirens was heard, not emerging until the all-clear sounded. On one such occasion, my weary mother, after spending an uncomfortable night in the cramped and ill-smelling underground refuge, could stand it no more. It was already early morning and even though there had been no all-clear siren, there had also been no air-raid and she was sure, as sometimes happened, it was all a false alarm. Seeing everyone around her asleep, she picked me up and, crossing the garden, took me back into the house. She was filling a basin with water to give me a bath when she heard the ominous sound.

The Germans had fired what was referred to as a “doodlebug”, also known as the V-1 flying bomb. A precursor of the modern cruise missile, it emitted a loud and dreaded buzzing sound as it descended on its target. As the fearful sound began, my mother knew what was coming; she placed me on the floor and flung herself protectively on top of me. The missile fell one block away from our home, demolishing houses, killing families in an instant. Even though our home escaped devastation, all the doors and windows blew out. My mother and I survived with no more than cuts and bruises.

As I tried to pick Roy’s mind for information about our parents, I recounted this memory to him.

“You could not have remembered any of that,” my brother told me firmly. “You were only a few months old.”

“But I do remember,” I replied. I heard again the bomb descending, I could remember the pressure of my mother’s body upon me, the blast as the windows shattered, the glass fragments raining down upon us, the cuts, and the blood.

“Before three or four years old, you don’t remember much. It’s called infantile amnesia,” Roy replied. He is a doctor, a father of four and many years older than me.

“I however do remember that night,” Roy continued. “I was already 12 years old when it happened. I remember every detail,” he said, reprimanding me.

Of course he was right. I did not remember that early morning at the beginning of my life. My mother had later told me about it in much detail. My memory is her memory of a harrowing experience we both shared. She passed onto me her vision of those terrifying moments, and it is her sense of fear and panic that is so deeply and permanently imprinted on my psyche. Although I was indeed too young to form a memory, I nevertheless feel I have some valid claim to the recollection. The experience was a shared one: it happened to me just as much as it happened to my mother. Through her, I have a memory of an event I experienced but cannot remember. That proxy memory holds a certain degree of validity. Other flights of memory are more difficult to explain.

In his book Hallucinations, the neurologist and writer Oliver Sacks says, “We now know that memories are not fixed or frozen… but are transformed, disassembled, reassembled, and recategorized with every act of recollection.”3

Sacks had evidence of this in his own life. In his memoir, Uncle Tungsten, he describes two incidents that also occurred in the war when, like my brother, he was 12 years old. He first describes the night a bomb fell into the next-door garden but failed to explode, and how everyone in the street ran out of their houses in terror. The second incident concerned a much smaller bomb that fell behind Sack’s family home. That bomb, too, failed to explode and slowly incinerated, burning brightly all the while. Sacks recounts how he and his brothers carried pails of water to fill a pump from which their father doused the melting bomb. After Uncle Tungsten was published in 2001, Sacks spoke about these incidents to one of his older brothers.4

Sack’s brother confirmed the first incident, saying he remembered it clearly but, regarding the second incident, what he tells Sacks comes as a great shock.

“You never saw it, you weren’t there.”

In the book, Sacks records his disbelief at this revelation.

“What do you mean?” I objected. “I can see the bomb in my mind’s eye now, Pop with his pump, and Marcus and David with their buckets of water. How could I see it so clearly if I wasn’t there?”

“You never saw it,” Michael repeated.

Sacks and his brother Michael had been evacuated with their school to the countryside, but an older brother, David, had sent them a vivid letter that had enthralled the young Sacks.

“Clearly, I had not only been enthralled, but must have constructed the scene in my mind, from David’s words, and then taken it over, appropriated it, and taken it for a memory of my own,” Sacks writes.5

What are we doing when we appropriate memory in this way? According to Sacks we are fashioning our own life narrative, our identity. This need for narrative to make sense of our lives is peculiar to our human condition. Such convoluted introspective reflection is unknown in animals. We are the only species that can reflect upon ourselves.

In his book, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat and Other Clinical Tales, Sacks says, “To be ourselves we must have ourselves – possess, if need be, re-possess, our life-stories. We must ‘recollect’ ourselves, recollect the inner drama, the narrative, of ourselves. A man needs such a narrative, a continuous inner narrative, to maintain his identity, his self… Our only truth is narrative truth in the stories we tell each other and ourselves… Such subjectivity is built into the very nature of memory.”6

Without the framework of narrative, the events in our lives would be just that, isolated events we live through, today’s happenings unconnected to tomorrow or yesterday’s experiences, free of meaning or the power to shape our identity. All writing, whatever the genre, is about what it means to be human, and all writing taps into universal experiences. The subjectivity that Sacks observes is built into the essential nature of memory and is the narrative thread by which we link one thing to another and make sense of our lives. Our stories mould our beliefs and make us who we are. They determine how we look at the world and how we treat others. Through narrative, we come to better understand the hand we have each been dealt in our life, and to use that insight in often transformative ways.

In writing a memoir of my father, I see that my mission is not only to understand the difficult hand fate dealt him, but to shape a narrative of his unique experiences in a way that he could not. While immersed in the day-to-day living of his life, he had no thought to share his story with the world. It is my task to do that for him.

When I sit down to write, there will be things I will not get exactly right, there will be gaps, there will even be things I miss entirely. However, it is my hope that the main arc and intent of my father’s life will be visible in a way it was not before. This is all that matters. Such narrative-sharing illuminates our hidden depths and common humanity and enriches the world through new threads of connection and empathy. That is the purpose of memoir, and to my brother’s delight, I push on.

A memoir may be a historical account, or a biographical memory written from personal knowledge, but facts remain facts and cannot be moulded to the author’s liking as they can in fiction. Memoirs often necessarily delve into past times or historical episodes, and getting facts right is of the utmost importance. If facts do not ring true then the finished work does not hold verity; the author will be seen as unreliable and the work will not be taken seriously.

I can give a small example of this. As a young writer, I was horrified after the publication of my first novel, The Gossamer Fly, in 1979 to receive an irate letter from a nature lover complaining that I had written about dragonflies emerging about two months before the correct season. This showed me forevermore how careful an author must be to get even the smallest facts right.

Anyone in Singapore thinking to research and write a memoir is fortunate. Singapore has made enormous efforts to document its short modern history. There is an abundance of material assiduously collected in a variety of archives. For the research of my novels, A Different Sky (2010) and Sacred Waters (2018), I will always be grateful to the National Library Singapore and the National Archives of Singapore for not only their wide collection of books but also for their archives of photographs and rare items. Without the indispensable material I found in the Oral History Centre, with its wealth of recordings and transcripts; the online NewspaperSG collection, with newspapers that go back as far as 1827; and the 2.3 million photographs in the National Archives of Singapore, my books could not have been written.

Such a treasure trove of research material allows an author to not only crosscheck facts but to expand and fill out a memory or historical picture that may be otherwise incomplete. Or, as was the case for me, grow a whole new virtual memory.

Notes

-

Dani Shapiro, Still Writing: The Perils and Pleasures of a Creative Life (New York: Grove Atlantic, 2013), 183. (From NLB OverDrive) ↩

-

Meira Chand, A Different Sky (London: Random House, 2010). (From NLB OverDrive); Meira Chand, “A Journey into Memory,” BiblioAsia 10, no. 1 (April–June 2014): 10–11; Meira Chand, “A Different Sky: The Other Side of the Looking Glass,” BiblioAsia 16, no. 3 (October–December 2020): 44–47. ↩

-

Oliver Sacks, Hallucinations (New York, Toronto: Alfred A. Knopf, 2012), 93. (From NLB OverDrive) ↩

-

Oliver Sacks, Uncle Tungsten: Memories of a Chemical Boyhood (New York, Toronto: Alfred A. Knopf, 2013), 22–24. (From NLB OverDrive); Oliver Sacks, “On Memory,” The Threepenny Review, Winter 2005, https://www.threepennyreview.com/on-memory-winter-2005/. ↩

-

Sacks, Uncle Tungsten, 22–24. ↩

-

Oliver Sacks, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat (New York: Picador, 2014), 101. (From NLB OverDrive) ↩