Luís de Camões in Asia

Portugal’s most important poet was once imprisoned in Goa, saw fighting in Ternate, was shipwrecked near the Mekong Delta and worked as the Superintendent for the Dead and Missing in Macau.

By Isabel Rio Novo

In April 1553, the fleet that set sail from the port of Lisbon bound for the East carried on board, among its men-at-arms, a young man in his 20s who had been released from prison just over 15 days earlier. He had been arrested in June the previous year for having slashed a servant of the king with his sword during a solemn religious procession. Using a common legal expedient of the time, the young man had begged the king’s pardon in exchange for serving him in India, and the king had granted him this favour.

Like many of the men who went aboard ships to defend the military positions that the Portuguese had conquered in the East, this young man was a squire, a member of the lesser nobility without a noble title or fortune, with nothing, really, apart from some distant family ties with certain noble families and an extraordinary humanist culture, acquired in Coimbra, the university city, where he had studied thanks to an uncle. In Lisbon, he became known by his gifts of poetic improvisation, which he demonstrated in palace evenings and in some plays, but also in taverns and brothels where he lived among sailors, soldiers, slaves and prostitutes.

The young man already had his brushes with the law, caused by his tempestuous temperament and aggravated by a forbidden love affair with a lady of the queen who was well above his social position. He had even served as a soldier in North Africa, near Ceuta, where a spark from a cannon fired near him had gouged out his right eye, disfiguring him for the rest of his life.

Even if this impediment had not been a condition inherent to his release from the shackles of the Lisbon prison, leaving for India was the natural option for any member of the Portuguese lower nobility in the mid-16th century, who hoped to be enriched or become great through a career in arms. The difference is that Luís Vaz de Camões, as the young man was called, was a poet of exceptional talent.

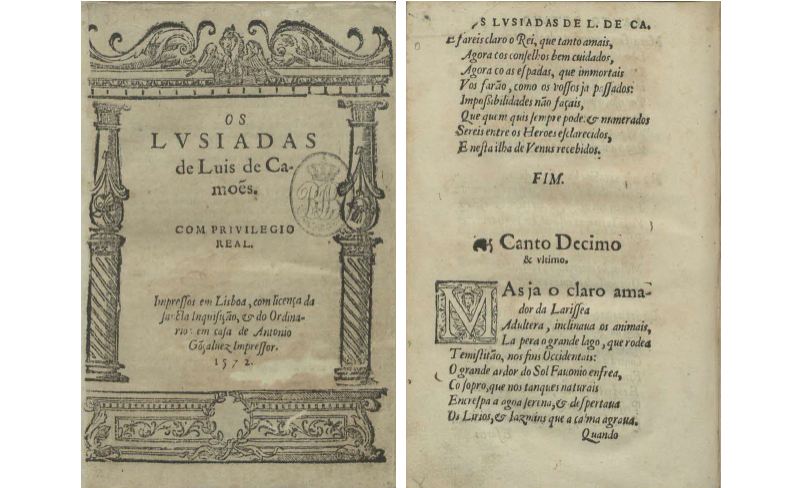

Born in Lisbon in either 1524 or 1525, Camões is considered Portugal’s greatest poet and has been compared to Shakespeare, Milton, Homer, Virgil and Dante. Camões is the author of Os Lusíadas (The Lusiads), first published in 1572, an epic poem that is regarded as the most important work of Portuguese literature (Lusiads means “Portuguese” and comes from Lusitania, the ancient Roman word for Portugal.) Comprising 10 cantos, 1,102 stanzas and 8,816 lines of verse, the poem celebrates Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama’s discovery of a sea route to India.

What also makes Os Lusíadas interesting is that this epic Portuguese poem has strong links with Asia. Camões spent 17 eventful years outside Portugal, living mainly in Asia, and wrote most of The Lusiads during his time in the region. While he was here, he fought in wars in India and Indonesia, was imprisoned in Goa, and sailed past Singapore while heading north to Macau where he lived briefly. He was shipwrecked in the South China Sea on his way back to Goa and lived in poverty in Mozambique. Not surprisingly, parts of his epic poem draw directly from his many experiences and from his keen observations of people and places.

Life in Goa and Beyond

Camões arrived in Goa after six months of “bad living”1 – the normal duration of a voyage across the Atlantic Ocean, rounding the Cape of Good Hope at the tip of Africa, and repeating the route that the navigator Vasco da Gama had first taken in 1497. The poet’s journey was not one of the worst, despite the terrible storms, the illnesses on board, and the constant shortage of food and fresh water, which he would later describe in verse. Upon disembarking, India seemed to him, as it did to any European of his time, like “another world”.2

There was the heat, the lush vegetation, the unfamiliar aromas, the people of different races – with peculiar clothing and manners – and speaking a variety of languages. Among the Indians, a keen eye like Camões’ would quickly distinguish the light-skinned, mystical-looking Brahmins, who “do not kill living things”, from the darker-skinned untouchables, who performed the hardest or most ignoble tasks.3 The discovery of the caste system would be described in The Lusiads, as would other aspects of Hinduism, such as the tradition of individuals going to die in the Ganges River.

Afonso de Albuquerque, the first Portuguese viceroy of India, had conquered Goa in November 1510, after bloody battles that Camões would recall in his epic poem. Four decades later, the city that served as the Portuguese capital of the East had preserved traces of the Portuguese victories (some of them still visible today), both in its architecture and in the testimonies of the elders who had taken part in the events.

The Portuguese heroes that Camões had read about in chronicles were there, buried under the slabs of churches, remembered on tombstones and depicted in portraits displayed in the palace of the viceroys, also known as the Savoia palace. The buildings, the statues, the churches that had been built, the wall that had defended the city of Goa, which had been torn down in some places, and the red earth that Camões had walked on had been conquered at the cost of much bloodshed. His project for an epic poem that would become The Lusiads, which had certainly begun to germinate in his youth, was growing stronger.

The strategy of Portuguese rule in Asia was not the total conquest of the territory, but the possession of a series of trading posts on the coast – the so-called feitorias – which were supported by fortresses and a permanent military force. For this reason, the life of the men-at-arms in India was a continuous series of land and sea expeditions.

Each year, several fleets set out from Goa to defend the regions that were important for dominating trade. One fleet, known as the Northern Fleet, headed towards the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea, where the Portuguese captains went to the Strait of Hormuz to await Turkish ships, with the dual objective of preventing their passage and seizing their cargo. The conquest of the city of Hormuz, at the mouth of the Persian Gulf, allowed the Portuguese to control this narrow and obligatory passage between the Arabian Sea and the Persian Gulf, through which, before the route around the Cape of Good Hope was discovered, goods from the East and the West were traded.

Another fleet, known as the Southern Fleet, set out from Goa, skirted the western coast of Malabar as far as Cape Comorin (now known as Kanyakumari in Tamil Nadu) at the southern tip of the Indian subcontinent, then rounded it and continued to Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka). In addition to these regular fleets, others set out sporadically for any point in the East where the Portuguese had economic or military interests, such as the Sunda (the term used to refer to the islands of Sumatra, Java and the Moluccan archipelago), China or Japan.

Camões had gone to India as a soldier and, less than two months after his arrival in Goa, embarked on a military expedition to intervene in a conflict between two Indian kingdoms over some islets. Now, while one of those kingdoms was a vassal of Portugal, the other was on the side of the Zamorin of Calicut (the hereditary ruler of the Kingdom of Calicut, a prominent trading centre on the Malabar Coast in southern India) and was hindering the Portuguese trade in precious pepper. The Portuguese, who were greater in number, had advanced weapons, while the subjects of the so-called King of Pepper fought with bows and arrows. The battle was devastating for the population of the islets. When narrating in verse his military debut in the East, Camões did not give in to any heroic impulses, but rather spoke of the vanity and cruelty of war: “I saw in our own people such hauteur / and in the land’s owners so little, against whom / it was at once necessary to make war.”4 It seems certain that, from the beginning, the life of a soldier in the East disappointed him.

Imprisonment in Goa

After a second military campaign in the Persian Gulf, Camões returned to Goa in early 1554. The city, and in fact the entire Portuguese East, seemed to him a “Babylon, from which flows / the material for all the evil the world creates”. A system of corruption, extortion, venality and despotism was rife in all strata of society. Even soldiers and sailors, as Camões had witnessed, were not exempt from unworthy acts, for during military campaigns they plundered and murdered cruelly. Giving voice to his indignation, Camões wrote satirical poems criticising the prevailing corruption and debauchery. And since satire was forbidden by law, he was incarcerated in the Goa prison by Governor Francisco Barreto.

There is a portrait of Camões by an unknown artist, dated 1556, showing him in a prison cell overlooking the Mandovi River in Goa.5 He is sitting at a table on which rests an inkwell with two feathers and some handwritten sheets. Behind Camões, we can see part of a narrow cot, with a sea chart unfolded on it. Above the cot, there are two suspended shelves with several bound books. Camões is dressed in civilian clothes. He is imprisoned, it is true, but he seems to enjoy some privileges. His feet are not shackled, and he is seated at his worktable surrounded by the tools of his trade.

On the topmost sheet of paper on the table, we can make out “Canto X” (the last canto of The Lusiads). If we had any doubts about the long years of preparation, versions and successive revisions that Camões dedicated to his epic poem, this portrait dispels them. In Goa, Camões was already working on the last canto of The Lusiads, the one that mentions the regions of the Far East. At the time the portrait was painted, it is likely that the poet needed maps as he had not yet visited these places.

Sojourn to Southeast Asia

Prison, however, was only the first part of the punishment. After a few weeks, in 1556, Camões was exiled: he was sent on the Maluco voyage or the China voyage, the two main routes that the southern fleets followed in the 16th century, connecting Goa to the most distant regions of East Asia. The dangers of these distant seas and these regions – where Portuguese presence was still so tenuous – were extremely grave that despite economic incentives, not everyone was willing to go there. Hence, the majority of those who travelled to these lands were poor soldiers or those who had incurred disciplinary penalties, like Camões.

In April 1556, the Southern Fleet, which Camões was following, set out from Goa, sailed along the western coast of India, stopped at Cochin and rounded Cape Comorin. From there, the ships turned eastwards to avoid the dangerous southerly winds and sailed as close as possible to the eastern coast of India until they gained the necessary length to reach the channel between the Nicobar Islands and from there enter the Strait of Melaka, the richest port of call in the East.

Whoever controlled Melaka, and at the time it was the Portuguese, effectively controlled the routes through the straits that allowed them to reach the great centres of production of spices and other luxury goods, namely China, Japan and the Moluccas. Camões saw, among other things, cloves from the islands of Tidore and Ternate, cinnamon from Ceylon, nutmeg from Banda, white sandalwood from Timor, camphor from Borneo, benzoin and gold from Sumatra, silver and copper from Japan, and porcelain from China and Siam.

From Melaka, Camões set sail for Ternate in the Moluccas archipelago, the island where an active volcano, a rather unusual sight for a Portuguese from the mainland, impressed him. He described the “boiling / peak, which throws out the billowing flames” in the verse, “With Unusual Strength”.6 In Ternate, where the Portuguese had settled since the 1520s, Portuguese influence had been declining for some years, and there were frequent revolts against the captains, who were mainly interested in their personal affairs and who cruelly repressed the locals.

Given that Camões left Goa in 1556 and that he spent “a large part of his life” in Ternate and, no less importantly, that he refers to the orders of “fierce Mars” (the Roman god of war), it is almost certain that the poet was involved in the serious events that took place in Ternate in 1558. Captain-General Duarte de Eça, wanting to seize the clove spice of the island of Makian which belonged to Sultan Hairun of Ternate, invented a pretext to imprison the latter and his family in inhumane conditions. Outraged, the inhabitants of Ternate reached an agreement with the neighbouring king of Tidore and attacked the Portuguese fortress. Duarte de Eça’s stubbornness and relentless cruelty eventually led to a revolt by the Portuguese themselves. Soldiers and locals arrested the captain of Ternate and freed Sultan Hairun and his family.

We do not know how Camões took part in these battles, whether among the soldiers who remained loyal to Duarte de Eça or among those who rebelled against the captain of the fortress. We do know that around 1560, Camões was back in Goa, having taken from the Moluccas – in addition to the scars and memories stained with “blood and regret” – another dose of deep disillusionment. But this first trip through the most remote regions of the East would later allow him to describe them with the truthfulness of an eyewitness.

Stopover in Singapore and Life in Macau

In 1562, India was governed by D. Francisco Coutinho, Count of Redondo, who favoured the poet, appointing him Superintendent for the Dead and Missing for Macau on the voyage to China, a modest administrative position. Whenever someone died, the superintendent identified the deceased, sold their assets and kept the money collected so that it could later be forwarded to the legitimate heirs.

Camões set off in 1562 with Captain Pero Barreto, to whom the voyage had been assigned. The itinerary from Melaka to Macau was recorded in Canto Decima, or Canto X, of The Lusiads.7

The Portuguese ships bound for the Chinese coast left Melaka and stopped at “the tip of the land, Singapore […], where the path for the ships narrows”. Going up the coast, they touched the kingdoms of Pam and Patane, on the eastern coast of the Malay peninsula, where they made a stopover. From there, crossing the Gulf of Siam to the northeast, they saw “the length of Siam” and its river Menon, which bathes “a thousand unknown nations”. They then headed for the island of Pulo Condor, located on the southeast coast of the Indochinese peninsula, bordering Cambodia and within sight of the Mekong and Champa rivers. From Pulo Condor, the route of the Portuguese ships followed northwards, along the coast, skirting the coast of “Cochinchina” (now known as Vietnam) to Pulo Catão, an island located at the southern entrance to the Gulf of Tonkin. Passing south of the large island of Hainan, the Portuguese were already skirting the “proud empire” of China. The ships then headed for the islands off the coast of the Chinese province of Guangdong. In 1562, the port they called at was Macau, where the Portuguese had recently established themselves. It was the port of departure for goods from China and the port of entry into the Middle Kingdom for products from Goa, Melaka, the Moluccas and Japan.

Although there is no documentary evidence, it is difficult to doubt that Camões spent time in Macau, as attested by ancient biographers and memorialised in the famous Camões cave in Patane (a grotto within the Luís de Camões Garden in Macau) where the poet is believed to have spent time and written his epic poem. Interestingly, a late manuscript by the Jesuits in Macau records the sale by the priests of a plot of land identified as “the ground of Campo dos Patanes next to the rocks of Camões”, showing that, beneath the legend, there must be a grain of truth.8

In Macau, Camões was assured of his livelihood, lived with a Chinese girl and had the peace of mind to finish The Lusiads. However, in 1564, another captain arrived in Macau. Dismissed from his position, Camões was due to return to Goa but on that voyage, he was shipwrecked somewhere in the South China Sea, near the Mekong River Delta, managing to save himself “on a raft”. He described this shipwreck in his epic poem, referring to the Mekong as the “captain of the waters” who welcomed him calmly and gently after the shipwreck. Camões had lost his Chinese companion, his personal belongings, the estate of the deceased in his care, but he managed to save the manuscript of The Lusiads, the “wet poem”, as he calls them, alluding to the fact that they were rescued from the water.

Rescued, it is not known exactly when or how (Wilhelm Storck, a 19th-century biographer, suggests that Camões and the other survivors may have been welcomed by some Buddhist community, and, in fact, in the passage in which he recalled his shipwreck, the poet made a sympathetic reference to the Buddhist people who lived on the banks of the Mekong9), Camões arrived in Goa without the funds for the deceased for which he was responsible. He became the subject of an investigation and the few possessions he had managed to save from the shipwreck were confiscated as compensation. A decade and a half after disembarking at the Santa Catarina pier in Goa, Camões was still poor and had no reason to want to remain in India. His wish was to return to Lisbon and publish The Lusiads.

Pero Barreto, the new captain of Sofala and Mozambique, with whom he had earlier travelled to Macau, offered him passage. But the two men subsequently broke off relations and Camões was stranded on the island of Mozambique, where he remained for almost two years in extreme poverty since he had no money to pay for passage on another ship. He was helped by the future historian Diogo do Couto and some friends who paid for his trip to Lisbon.10 Camões bade a farewell to the East, where he had lived for 17 years.

Return to Lisbon

Camões arrived in Lisbon in April 1570 and published The Lusiads in 1572. This modern-day epic, celebrating the voyages of the Portuguese and the glorious deeds of their recent history, was imbued with the experiences of its author. Like the poet’s life, his writing was also “scattered throughout the world in pieces”,11 as described in the verse, “Next to a dry, wild and barren mountain”, and much of that world was Asia.

Although his years of military service earned him a meagre pension of 15,000 reis per year and the publication of The Lusiads brought him some fame, Camões lived his last years destitute and ill. He had a few friends, his elderly mother who survived him and a former Jau slave (a term that, for the Portuguese of the time, included without distinction Javanese and Malays), who may have come with him from the East. This faithful friend, who begged for alms at night so that Camões’ house would not run out of coal, died a few months before the poet.

Luís de Camões, the greatest Portuguese poet, died on 10 June 1580 (today celebrated as the national day of Portugal) in a hospital in Lisbon “without having a blanket to cover himself with”.12

Isabel Rio Novo has a master’s degree in History of Portuguese Culture (Modern Period) and a doctorate in Comparative Literature from the University of Porto. She teaches art history and creative writing at the University of Maia, and has written academic publications in these fields. She is also a fiction writer. Her latest books are Fortune, Occasion, Time and Luck (2024), a biography of Luís de Camões and The Matter of the Stars (2025), which won the City of Almada Literary Prize.

Isabel Rio Novo has a master’s degree in History of Portuguese Culture (Modern Period) and a doctorate in Comparative Literature from the University of Porto. She teaches art history and creative writing at the University of Maia, and has written academic publications in these fields. She is also a fiction writer. Her latest books are Fortune, Occasion, Time and Luck (2024), a biography of Luís de Camões and The Matter of the Stars (2025), which won the City of Almada Literary Prize. Notes

-

Letter from Luís de Camões sent from Goa to a friend in Lisbon in 1554. The excerpts from Camões’ works cited in this article were translated by Isabel Rio Novo, from the edition by Maria Vitalina Leal de Matos of the Complete Works of Luís Vaz de Camões (Lisbon: E-Primatur, 2019). Volume I – Epics & Letters; Volume II – Lyric; Volume III – Theatre. ↩

-

Letter from Luís de Camões sent from Goa to a friend in Lisbon in 1554. ↩

-

Luís de Camões, Os Lusíadas (The Lusiads), canto VII, stanzas 38 to 40 (Lisboa, Portugal: Antonio Gonçalves, 1572), Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2021666936/. ↩

-

Luís de Camões narrated the expedition in verse in the elegy, “The Poet Simonides, speaking”. Simonides of Ceos (c. 556–468/7 BCE) was a Greek poet of the Archaic to Classical period. He was known for his diverse poetic forms, including elegies, epigrams and various lyric genres. ↩

-

The small parchment illumination was revealed by Maria Antonieta Soares de Azevedo, in an article published in 1972 in the magazine Panorama. The portrait was exhibited to the public in the same year at the National Library of Portugal in an exhibition to mark the fourth centenary of the publication of The Lusiads. The portrait now belongs to a private collector. ↩

-

Camões’ experiences on the island of Ternate were described in the verse, “With Unusual Strength”. ↩

-

Camões, Os Lusíadas (The Lusiads), canto X, stanzas 123 to 129. ↩

-

The manuscript, “Title of the real estate of this College of Macau”, an 18th-century copy of a 17th-century original, is held by the Biblioteca da Ajuda in Lisbon. ↩

-

Wilhelm Storck, Vida e Obras de Luís de Camões: Primeira Parte: Versão do Original Alemão Annotada por Carolina Michaëlis de Vasconcellos (Lisboa: Academia Real das Ciências, 1898), Biblioteca Nacional Digital, https://purl.pt/43902. ↩

-

Diogo do Couto described this meeting with Camões on the island of Mozambique in Da Asia de Diogo de Couto: Dos Feitos que os Portugueses Fizeram na Conquista, e Descobrimento das Terras, e mares do Oriente: Decada Sexta, Parte Primeira (Lisboa: Na Regia Officina Typografica, 1781), Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/A209014/page/n5/mode/2up. ↩

-

Luís de Camões, “Next to a dry, wild and barren mountain”. ↩

-

Note by Friar José Índio of the Discalced Carmelites of Guadalajara, Spain, on the title page of the copy of The Lusiads, Lisbon, Oficina de António Gonçalves, 1572, in the custody of the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center. ↩