Playing It Cool: The Early History of Air Conditioning in Singapore

The humble air conditioner is an innovation that we take for granted today. But for the people of Singapore in the mid-20th century, it was a luxury that only the affluent could afford.

By Fiona Williamson

Before the advent of air conditioning in Singapore, staying cool meant being creative and, ideally, well-off. The bungalows of the colonial elite, Chinese and Europeans alike, would be situated on higher ground with ample gardens to generate maximum exposure to breezes and cooling vegetation.

When the heat became too oppressive, these wealthy inhabitants had the means to relocate. After the arrival of the motorcar, the wealthy could circumnavigate the island, visiting the coastline or a swimming club. The beaches at Pasir Ris, Tanah Merah and Pulau Ubin were especially popular for swimming and relaxing. Government-owned beachside bungalows were let to civil servants for holiday rentals where one could “escape” to a “shady verandah, [with] lofty cool rooms, looking over calm waters to green islands”.1

To avoid “prickly heat” (heat rash), people were advised to avoid too much strenuous exercise, meat, strong drinks and bathing with cold water. Eating foods such as salads, ripe fruit and vegetables in moderation was particularly recommended as these “cool the blood”.2 Air conditioning changed the game, but it must be remembered that not everyone had access to, or even wanted, this new technology.

Benefits of Air Conditioning

Air conditioning first came to Singapore in the 1920s and the largest supplier of the technology during the inter-war era was the Carrier Air Conditioning Company of America. Carrier entered the Asian market in the early 1930s, subsequently setting up a regional headquarters in Singapore alongside Tokyo, Hong Kong and Sydney.3

The company operated locally through United Engineers Limited which employed Singapore-based contractors for all types of government and commercial air conditioning installations of that era, among other electrical work. As trade picked up from 1936, Carrier appointed a separate marketing representative for Singapore, and the company eventually spread north to Kuala Lumpur (1948) and Penang (1952).4

Air conditioning fits futuristic vision of modernity and progress, and the technology was closely aligned with ideas of health as much as simply staying cool. Air conditioning was hailed as an invention that would not only provide comfort but better health, as influenced by new concerns about industrial pollutants, motorcar fumes and dust in the rapidly growing town. In 1936, for example, a Morning Tribune staff writer concluded: “Singapore may be a beauty spot and its strategic position superb, but its climatic conditions have always been a moot point with residents and medical men alike. Its humidity or dampness is the sore point, but the marvels of modern science and invention can transform the air condition of the interior of Singapore’s buildings to the most delightful and healthiest obtaining anywhere.”5

The benefits to workplace productivity were also frequently cited by the press. In December 1937, the Malaya Tribune wrote: “Air conditioning has come as a boon to humanity. It had made it possible for men to work in places where the temperature previously rendered it impossible for them to carry out their employment.” The newspaper added that the technology reduced the incidence of tuberculosis, then a major scourge for Singaporean inhabitants, and also contributed to increased efficiency among workers.6

Two years later, a study on air conditioning in the tropics was published, which praised its “valuable contribution” in improving mortality outcomes in hospital surgeries and in infant nurseries, due to reducing the effects of outdoor air pollution by cleansing indoor air.7

In June 1938, the Morning Tribune explained that the main purpose of air conditioning was not to cool but to remove the excess moisture which was considered dangerous to health. “[I]n Singapore, we have too much moisture in the air. The relative humidity is high. We become uncomfortable and suffer because perspiration and body heat are not removed fast enough,” the newspaper wrote. “Air conditioning, therefore, is called upon to remove the excess moisture and lower the relative humidity.”8

Air Conditioning in Singapore

Mechanical air ventilation systems for entertainment spaces in Singapore were the first iteration of the transition to modern cooled and healthy buildings.9 The new Capitol Theatre, for example, which opened in May 1930, incorporated a mechanical air cooling system in which air was circulated around the theatre from a suction fan in the basement passed through a ventilation system, which filtered, purified and “washed” the air before it was electrically charged in an Ozonair machine and pushed out into the theatre through air vents “with all the freshness of a cool breeze”.10

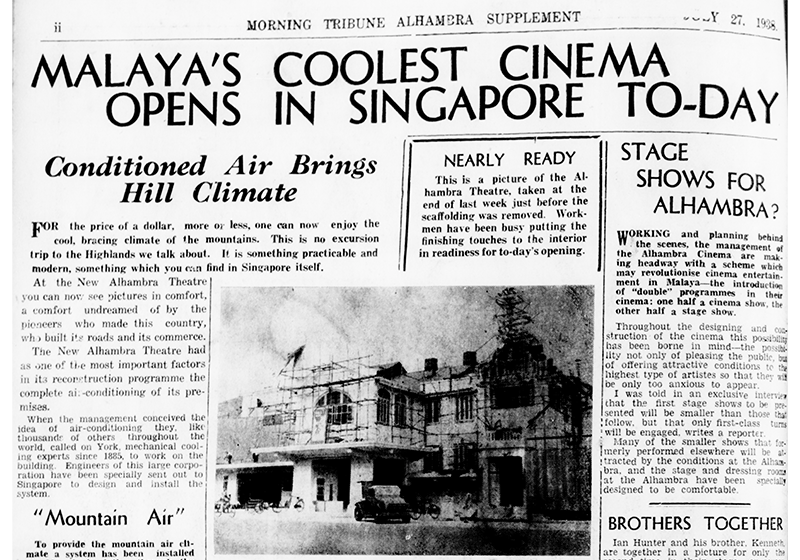

Within a decade, however, this cooling system was becoming obsolete. The Alhambra cinema on Beach Road is believed to have been the first movie theatre in Malaya to have modern air conditioning.11 When it reopened as the New Alhambra in July 1938, it had a new bar, seating and decor but it was the cool air which dominated the discussion at the VIP opening ceremony.

“Entertainment in the East is controlled for the most part by the problem of weather. It is a remarkable fact that the idea of installing an air conditioning plant has not been thought of before,” noted the Morning Tribune. “There is no doubt that the air conditioning is a huge success – all through the evening there was a pleasant sense of cool dehumidified air. It was perfectly cool and there was no suggestion of any intolerable heat that can so often ruin an evening’s entertainment.”12

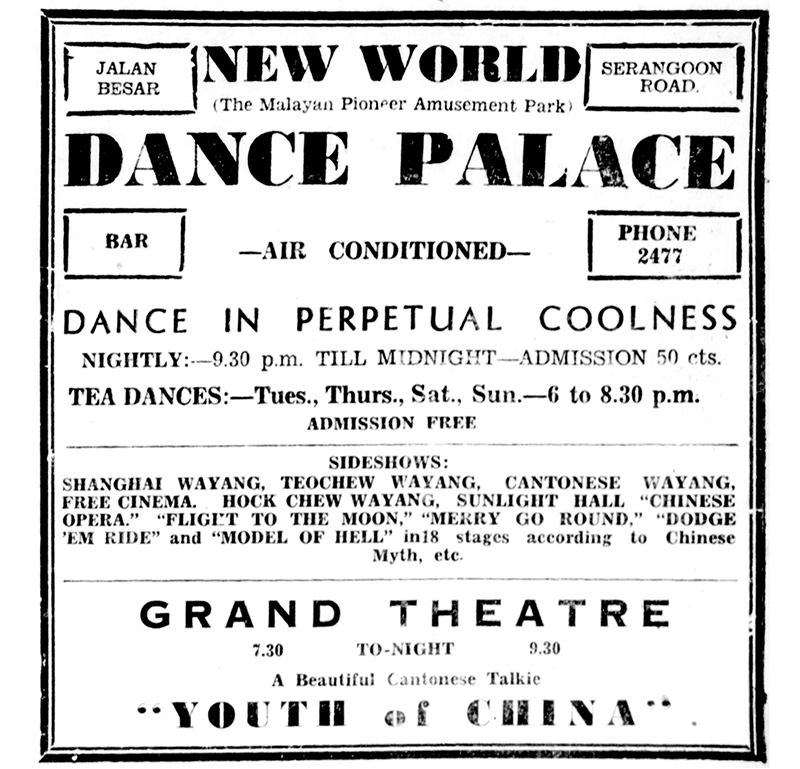

Before long, other entertainment spots in Singapore began incorporating air conditioning into their design as a marketing ploy. In 1938, the New World amusement park, which had opened in 1923, advertised its air-conditioned Dance Palace where patrons could “Dance in Perpetual Coolness”.13 Costing $48,500, the Straits Times wrote that the “air-conditioning plant has been designed to give the cool and refreshing atmosphere of a hill station, even when there are more than 1,000 people inside”.14

The Morning Tribune said that the dance and cabaret hall was “destined to be the most modern and luxurious in the whole of Malaya” and could “comfortably hold 1,500 people who can dance in a cool, dehumidified building”.15

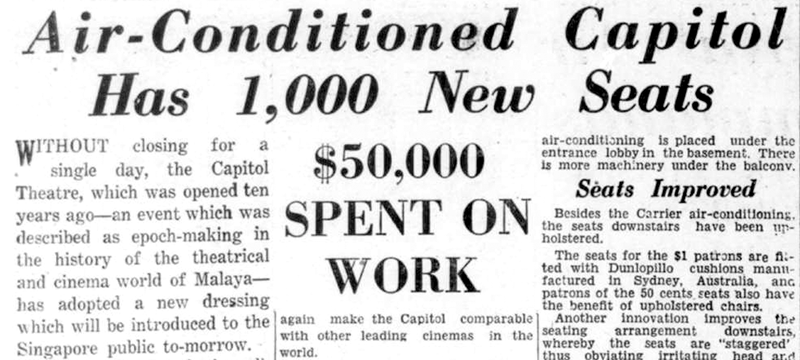

Not to be outdone, almost 10 years after Capitol Theatre first opened, the premises underwent a $50,000 refurbishment during which a new, modern air conditioning system was installed – all without closing the theatre. Completed in January 1940, the work involved a massive structural redesign, removing fans and ventilation shafts as well as adding a cooling tower in the roof to remove heat. Like many systems of the era, it was also designed to extract the vast amounts of cigarette fumes generated by public smoking, replacing the stale air with around one ton of new cooled air every minute. This was equivalent to melting 125 tons of ice per day.16

These entertainment venues were not the only places to install the new technology. Some other early beneficiaries of air conditioning in Singapore were the Singapore General Hospital, which installed air conditioning in two wards and the operating theatre in 1938, and the Singapore Dairy Farm, which introduced air conditioning for its cattle sheds on the basis that the cows would produce better milk. Dairy Farm cattle were imported Friesians whose native habitat is northern Europe.17

Selling the Future

In May 1938, the Sunday Tribune reported on a speech given by an electric company official in the United States. Selling the potential of electricity – from powering futurist domestic appliances to germ-destroying ultraviolet rays – the company representative said that by the 1960s, people could “live in a house lighted, cooled, humidified and air-conditioned by electricity”.18

This was the late 1930s, and there was already a sense that science and technology were not only part of the future but also of the present. This idea of a steady march of progress into a technological future, where cities would be fed by filtered air and artificial sunlight, had penetrated into the heart of the tropics, even if such futurism had been scoffed at earlier that decade.19

These technological innovations would be coupled with new styles of architecture “more suitable to the tropics”, the Straits Times wrote in March 1938, with “modern, flat roofed, reinforced concrete Singapore homes”. According to architects, air conditioning can be applied more easily to these homes, dispensing with mosquito nets and natural air flow.20 Such hyper-modern homes, in stark contrast to the very functional and elegant architectural cooling solutions of the 19th century, epitomised the future of housing in Singapore.

However, domestic air conditioning was beyond the reach of most low-income households. The price of the unit, its installation and running costs were considerations, but there were also many inconsistencies in the electrical infrastructure in colonial Singapore.

When it came to adopting air conditioning back in the 1930s, a press article from 1937 suggested that although the technology had been around for a decade, most people had not bought units for their homes or offices, which the writer blamed on “conservatism”. However, the story also noted the cost – around $600 per domestic installation – which was likely the real reason. To put this into perspective, a skilled labourer’s earnings were approximately $1.40 per day in 1939.21

This technological inequality is put into stark perspective by a story in the Singapore Free Press from 1926, when a heat wave saw “hundreds of Asiatic residents from the town districts… spending their nights in the open, the Esplanade having been the centre of unusual crowds during the evenings and nights for the past few days”. It was so hot that the newspaper reported it was “impossible to get a cold bath without the addition of ice” because only warm water came out from the taps.22

Likewise, in 1948, another heat wave sent people scurrying to the beaches in Katong and Changi and “while town dwellers who were fortunate enough to have a roof garden spent the night on camp beds in the open, others spent the night on five-foot ways, verandah and balconies”.23

Even for major commercial ventures and government institutions, air conditioning was unevenly appropriated. Not all cinemas were air-conditioned until the 1960s, for example, and many schools lacked any form of cooling technology, even fans in some cases.24

Brother Joseph Kiely, for example, had moved to Singapore from Ireland in the 1950s to work and live at the newly built brothers’ quarters of St Joseph’s Institution. He recalled how only the community room had air conditioning and as there were no fans in their individual quarters, he spent a great deal of time in the community room.25

Recollecting his time in Singapore from 1962 to 1965, Royal Air Force officer David Penberthy spoke of how air conditioning barely existed in Singapore. Until one acclimatised to the humidity, the only way to get to sleep was to have “two or three pints of Tiger”, he wryly noted. He could not recall air conditioning in “any of the private homes that [he] knew of, with perhaps one or two exceptions in the newer luxury apartment blocks that were going up at that time”. “In other words, we lived in exactly the same way as the local population lived – without air conditioning,” he said.26

Penberthy’s recollections suggest that the borders of who had, or had not, adopted this cooling technology were not clear. Indeed, according to Carrier’s records of the Far East, government ministries and embassies were the main beneficiaries of large-scale Carrier installations. Most restaurants, hotels, shopping malls and public housing projects started installing air conditioning only from the late 1970s or early 1980s onwards.27

Chan Thye Seng, a public servant who had been involved in expanding Singapore’s library service in the 1970s, recalled that even newly built libraries of that era did not have air conditioning. Instead, they had a high-ceiling design to assist in air flow within sections that were not artificially cooled.28

The early uptake of air conditioning in Singapore was patchy and often circumstantial. Sectors where air conditioning had evident benefit – such as at hospitals, dance halls or supermarkets – were early adopters, but for everyone else the transition was less clear.

In 1999, while Singapore’s first prime minister, Lee Kuan Yew, famously credited air conditioning with having “changed the lives of people in tropical regions” by enabling people to do useful work in offices despite the heat and the humidity outside,29 it would take some time before the benefits of air conditioning trickled down to the majority of people.

This essay is adapted from Chapter 7, “Regulating Heat, Controlling Urban Airs”, from Imperial Weather: Meteorology, Science, and the Environment in Colonial Malaya (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2025) by Fiona Williamson. The book is available for sale at online bookstores and for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library (call no. RSEA 959.503 WIL).

Fiona Williamson is Professor of Environmental History in the College of Integrative Studies and Associate Dean (Undergraduate Education) at the Singapore Management University. She is interested in the history of climate, meteorology and extreme weather in Singapore, Malaysia and Hong Kong.

Fiona Williamson is Professor of Environmental History in the College of Integrative Studies and Associate Dean (Undergraduate Education) at the Singapore Management University. She is interested in the history of climate, meteorology and extreme weather in Singapore, Malaysia and Hong Kong. Notes

-

Marjorie Binnie, quoted from Margaret Shennan, Out in the Midday Sun: The British in Malaya 1880–1960 (Singapore: Monsoon Books, 2015), 86. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 398.4 SKE) ↩

-

“Prickly Heat,” Singapore Free Press, 10 July 1889, 43; “The Prevention of Sunstroke,” Singapore Free Press, 18 July 1896, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Archive and Historical Resource Center, United Technologies Corporation: Anne Millbrooke, Carrier in the Pacific and the Far East (1983), Historical Report No. 32, Box No. 154393, 3. The author wishes to thank Chang Jiat Hwee, Dean’s Chair Associate Professor at the Department of Architecture, College of Design and Engineering, National University of Singapore, for sharing this file. ↩

-

“Untitled,” Malaya Tribune, 24 June 1938, 8. (From NewspaperSG); Millbrooke, Carrier in the Pacific, 34. ↩

-

“Modern Air-Conditioning System,” Morning Tribune, 30 March 1936, 15. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“A Boon to the Worker,” Malaya Tribune, 23 December 1937, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

R. E. Thompson, “Promoting Greater Efficiency and Less Fatigue,” Malaya Tribune, 10 July 1939, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“What Air-Conditioning Really Is,” Morning Tribune, 15 June 1938, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Joseph M. Siry, Air-Conditioning in Modern American Architecture (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2021), 12–18, https://www.psupress.org/books/titles/978-0-271-08694-1.html. ↩

-

“Sea Breezes at the Capitol,” Straits Times 29 April 1930, 19. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Grand New Alhambra Opens with Excellent Film,” Morning Tribune, 28 July 1938, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Weather Problems,” Morning Tribune, 27 July 1938, 7; “Grand New Alhambra Opens with Excellent Film”; “Grand New Alhambra Opens with Excellent Film (continued).” ↩

-

“Page 7 Advertisements Column 2: New World Dance Palace,” Morning Tribune, 28 July 1938, 7. (From NewspaperSG); Wong Yunn Chii and Tan Kar Lin, “Emergence of a Cosmopolitan Space for Culture and Consumption: The New World Amusement Park-Singapore (1923–70) in the Inter-War Years,” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 5, no. 2 (2004): 279–304, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1464937042000236757. ↩

-

“Singapore’s Latest Cabaret,” Straits Times, 15 May 1938, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Singapore’s Newest Cabaret,” Morning Tribune, 16 May 1938, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Bonny Tan, “Living It Up at the Capitol,” BiblioAsia 13, no. 4 (January–March 2018), 16–21; “Air-Conditioned Capitol Has 1,000 New Seats,” Straits Times, 31 January 1940, 15. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Friesians Will Form Nucleus of Local Dairy Herd,” Straits Times, 24 March 1946, 2; “Air Conditioning for Racehorses,” Malaya Tribune, 20 December 1938, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“An All-Electric World in 1963,” Sunday Tribune, 15 May 1938, 18. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The War of the Future,” Straits Times, 11 April 1930, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“New Architecture in Singapore,” Straits Times, 6 March 1938, 32. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Cool Comfort,” Morning Tribune, 11 August 1937, 10. (From NewspaperSG); Keen Meng Choy and Ichiro Sugimoto, “Staple Trade, Real Wages, and Living Standards in Singapore, 1870–1939,” Economic History of Developing Regions 33, no. 1 (2018): 18–50, 38, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/20780389.2018.1430512. ↩

-

“The Heat Wave,” Singapore Free Press, 14 April 1926, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Heat Wave: No Break in Weather,” Malaya Tribune, 11 June 1948, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Goh Eng Wah, oral history interview by Jesley Chua Chee Huan, 25 June 1997, MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 5 of 14, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 001907), 03:58. ↩

-

Patrick James Kiely, oral history interview by Rosemary Lim, 8 May 2008, MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 1 of 4, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 003297), 25:10. ↩

-

David Penberthy, self-recording, 1 April 2006, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 1 of 6, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 003074), 8–9. ↩

-

Millbrooke, Carrier in the Pacific, 3. ↩

-

Chan Thye Seng, oral history interview by Jason Lim, 10 May 2000, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 9 of 15, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 002265), 105. ↩

-

“Air-Con Gets My Vote, Says SM Lee,” Straits Times, 19 January 1999, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩