Rites of Rehabilitation: The Social Work of the Zhenkongjiao in Singapore

With its sometime unconventional treatments, the Zhenkongjiao worked together with local authorities to remove the scourge of opium addiction in Singapore.

By Esmond Soh

10 January 2025

Prayers, meditation, tea infused with prayers and even animal sacrifice – these were part of a plan to rehabilitate opium addicts in Singapore by a Chinese religious movement known as Zhenkongjiao in postwar Singapore.1

Chinese opium smokers, 1880s. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Chinese opium smokers, 1880s. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.The Zhenkongjiao are guided by religious texts known as the Four Books in Five Volumes, which are still recited today. The movement adheres to a syncretic belief system that integrates teachings from Confucianism, Daoism and Buddhism. This belief system accompanied its arrival in this region in the early 20th century. Zhenkongjiao temples feature five thrones – one for each of the movement’s patriarchs: Liao Dipin (b. 1827), Lai Renzhang (b. 1857), Ling Bangbi (b. 1849), Zhang Shengjian (b. 1852), and Lan Juying (b. 1859) – with altar walls displaying cosmology and ethical systems instead of deity images.2

The Zhenkongjiao’s scriptures and ethical systems were influenced by Mahayana Buddhist philosophies, but they also practised animal sacrifice through a ritual euphemistically termed the “scattering of flowers”. Livestock such as pigs and chickens were sacrificed to alleviate (the animals’) sponsors’ misfortunes and provide the sacrificed animals with a better afterlife.3 However, since the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak in Singapore in 2003, these ceremonies have ceased. Besides scripture recitation, the Zhenkongjiao also practise meditation and other therapeutic rituals such as sleeping on charcoal beds covered with sand in a ritual known as “laying in the emptiness”, performed in the pursuit of good health.

A survey of Zhenkongjiao temples on the island in 1968 found that there were as many as 25 of them in Singapore. Today, only six remain: Thian Ling Toh Tong in Bukit Batok, Poon Guan San Toh Tong in Pasir Panjang, Kong Leap Thiam Lim Tua in Geylang, Chin Kong Religion Fook Poon Tong in Yishun, Hean Thuan Toh Tong in Tampines Link and Fubenyuan Daotang (now located in a private residence, having moved from its original location in Hougang).

Early History of the Zhenkongjiao in Singapore

Zhenkongjiao was founded in Jiangxi, China, by Liao Dipin (1827–93) and popularised by his family members and disciples. Its influence expanded to southeastern China, particularly the regions of Guangdong, Fujian and Chaoshan. When the Chinese from these regions migrated to Southeast Asia during the 19th century, they brought Zhenkongjiao with them.4 The early pioneers of Zhenkongjiao in Singapore were mostly Hakkas from southeastern China, particularly the Jiaoling and Meixian regions in Guangdong.5

The inaugural Zhenkongjiao temple in Southeast Asia, Pili Hongmaodan Zhenkong Zushi Daotang, was founded in Ipoh in 1906 by Huang Shengfa and his teacher, Master Huang Daoyun. After struggling with opium addiction in Malaya, Huang Shengfa returned to Jiaoling, where Master Huang Daoyun treated him before accepting his invitation to Malaya. From Ipoh, the duo extended the influence of Zhenkongjiao in Malaya, each embarking on divergent paths. Huang Daoyun travelled southward to Singapore, where he founded the second-oldest temple in the region, Xingzhou Fubenyuan Daotang, in 1910.6 By 1929, five other Zhenkongjiao temples had been established across the island, founded by other masters of the movement who had travelled to Southeast Asia to proselytise. Later in his life, Huang Shengfa established Fook Poon Yuen Temple on Penang Island in Malaysia, which is still managed by his descendants today.

Fook Poon Yuen Temple on Penang Island is still managed by the descendants of Huang Shengfa, 2019. Photograph by Esmond Soh.

Fook Poon Yuen Temple on Penang Island is still managed by the descendants of Huang Shengfa, 2019. Photograph by Esmond Soh. A banner owned by Huang Shengfa advertising Fook Poon Yuen Temple’s service of treating opium addicts and curing illnesses. It was hung from the temple’s second floor when it operated out of a shophouse. The banner is held by Huang’s grandson, 2019. Photograph by Esmond Soh.

A banner owned by Huang Shengfa advertising Fook Poon Yuen Temple’s service of treating opium addicts and curing illnesses. It was hung from the temple’s second floor when it operated out of a shophouse. The banner is held by Huang’s grandson, 2019. Photograph by Esmond Soh.Aside from Huang Daoyun and Huang Shengfa, four other practitioners (along with their disciples) can be credited with growing the movement’s presence and renown in Southeast Asia: Xu Rukan (1874–1910), Su Wenlong (1876–1963), Huang Dazhong (1885–1950) and Lin Huawen (most active in 1925).7

When Xu’s disciple Zhu Wenxiu cured the rubber magnate Li Xiujiao of an ailment, his grateful Peranakan wife, Ruan Yang, became Zhu’s disciple. She gifted a seaside villa to the Zhenkongjiao, which is where Poon Guan San Thoh Tong temple stands today in Pasir Panjang in Singapore.8 Su Wenlong, another key figure, established temples in Hat Yai, Thailand and Malaya. He served as the resident master in Fook Poon Tong (then in Admiralty in Singapore) until his death in 1963.

By the 1960s, the number of Zhenkongjiao temples in Singapore had increased to 25, from five in 1929.9 The reasons for the boom in temple construction during this period are uncertain and difficult to trace. However, one interesting hypothesis proposed by researchers Ouyang Banyi and Shi Cangjin suggests that the boom in the movement’s popularity from the 1930s could be traced to the Great Depression (1929–39).10

Singapore, as the proverbial entrepot of Southeast Asia, was greatly affected by the shrinking trade quantities during the Great Depression, and the consequent fall in the trade of commodities such as rubber, rice and tin on the international markets had an adverse impact on the lives of ordinary workers.11 Many of them were frequent traffickers and consumers of opium – for both medical purposes and as an escape from the drudgery of their lives. With the rising cost of opium, it became increasingly necessary for them to break the habit. This may have provided the initial impetus for the growth of Zhenkongjiao in Singapore before the Second World War (1942–45) as addicts sought to quit opium smoking.12

Curing Opium Addiction in Postwar Singapore

After the Japanese Occupation ended in 1945, British authorities took notice of the Zhenkongjiao’s efforts to stamp out opium smoking, which aligned with the Opium and Chandu Proclamation that made the use and possession of opium and smoking tools illegal as of 1 February 1946.13 However, an intriguing narrative from Supplementary Histories, a commemorative volume published by the Zhenkongjiao in British Malaya in 1965, recounts the tale of Huang Shengfa, who was said to have received official authorisation in 1912 to disseminate the movement’s teachings in Singapore and Malaya after successfully treating terminally ill patients referred by British authorities.14

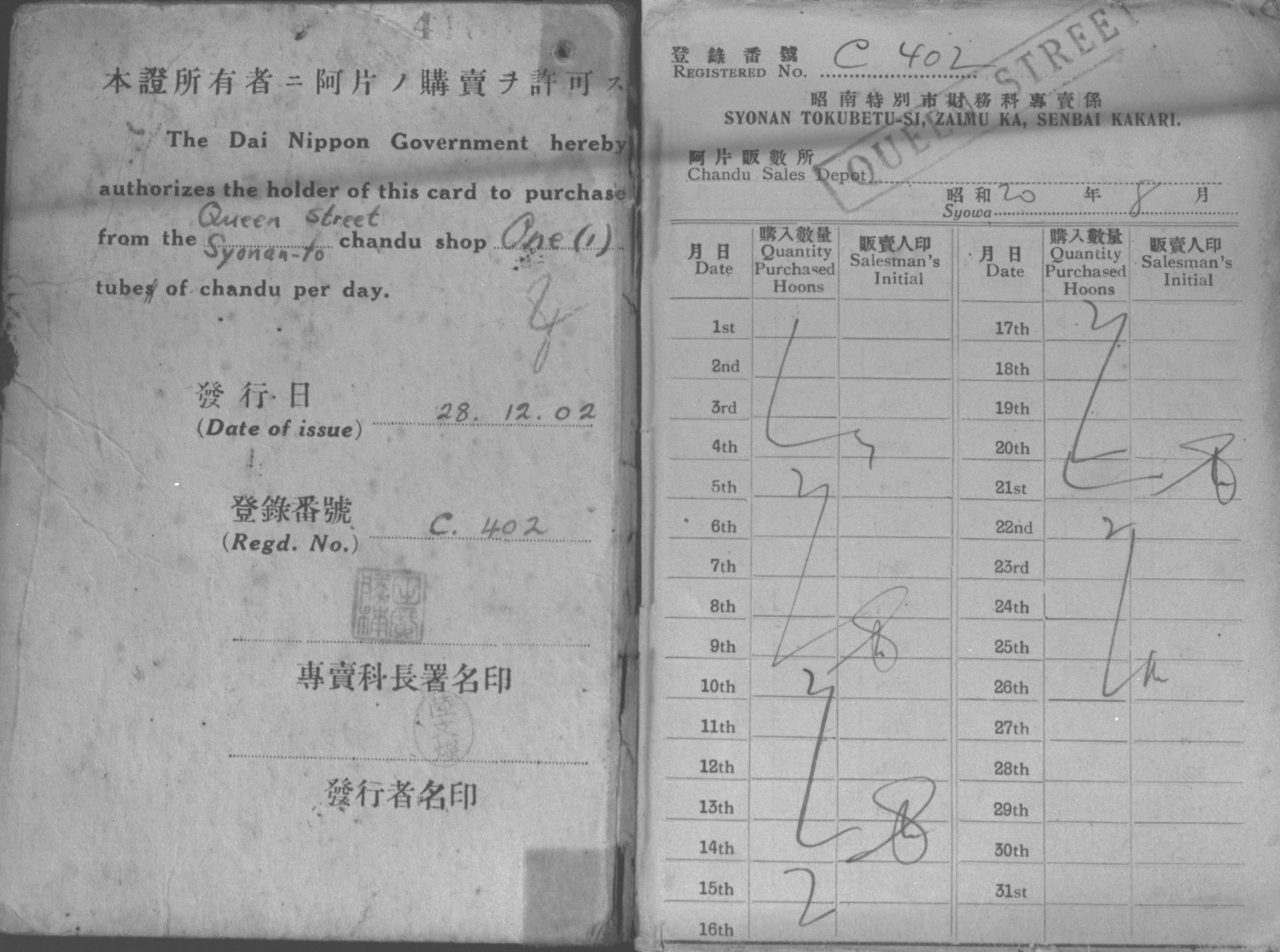

Authorisation card to purchase opium from an opium shop on Queen Street, Syonan-to (Singapore), during the Japanese Occupation, 1942. Chew Chang Lang Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Authorisation card to purchase opium from an opium shop on Queen Street, Syonan-to (Singapore), during the Japanese Occupation, 1942. Chew Chang Lang Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.However, not everyone was convinced of the Zhenkongjiao’s methods. Throughout the 1950s, the Zhenkongjiao and medical professionals clashed in newspaper forums and editorials, with the latter denouncing their rituals as “nonsense”. The Thian Ling Chong Toh Tong temple responded by issuing a challenge, which went unanswered, to detractors to prove their methods did not work.15 Despite scepticism from some quarters, the judiciary sentenced convicted addicts to the Zhenkongjiao’s opium rehabilitation programme, underscoring the relationship between colonial interests and the Zhenkongjiao.16

By 1956, there was growing acceptance by the government, with Thian Ling Chong Toh Tong temple being interchangeably referred to in the English press as the secular-sounding “Opium Addicts Treatment Association” and “Faith Healing and Opium Curative Centre”.17 A Dr Leong Hon Koon, representing the authorities, praised the temple’s methods, contrasting them with the relatively higher relapse rates of those who had been treated at the Opium Treatment Centre on St John’s Island, where similar cold turkey methods were used but with less success.18

Group photograph taken with Chief Minister Lim Yew Hock during the opening of the Opium Addicts' Treatment Association's Chinese temple on Changi Road, 1956. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Group photograph taken with Chief Minister Lim Yew Hock during the opening of the Opium Addicts' Treatment Association's Chinese temple on Changi Road, 1956. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore. Recovering addicts learned skills such as sewing at the Opium Treatment Centre on St John’s Island, 1957. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Recovering addicts learned skills such as sewing at the Opium Treatment Centre on St John’s Island, 1957. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.The Zhenkongjiao’s leaders saw opium addiction and its presence in the form of a physical taint that could be metaphysically removed from one’s body through rituals. Thian Ling Chong Toh Tong temple reportedly told addicts that “there is opium in your bones, there is opium in your teeth, now it is leaving you,” before serving tea that had been prayed over.19

Temples in Singapore and Malaysia also provided charcoal beds covered with a layer of sand for recovering addicts to sleep on. Known as “sleeping or laying in emptiness”, it was believed that the charcoal would draw out and absorb the opium residue from the addicts, along with other illnesses within the body. In the 1950s, Thian Ling Chong Toh Tong temple integrated sand beds into its courtyard and provided pillows and blankets for patients to use.20 In Singapore, the last remaining sand bed for the practice of “laying in emptiness” as a form of health and bodily therapy is located at Fook Poon Tong Temple in Yishun and remains in use today.

Other unconventional treatments included massage. In 1930, it was reported that a Zhenkongjiao temple on Tras Street in Singapore had blind masseuses massaging the atrophic limbs of these addicts while they participated in tea-drinking and exercise-worship sessions every night.21

In addition to massage, tea drinking and “laying in emptiness”, the addicts also underwent a combination of going cold turkey, cold water baths and generous meals, as it was believed that they were typically ravenous and needed sustenance during their recovery.22 However, earlier articles reported that recovering addicts instead lost their appetites.23

Animal Sacrifice and Embodied Sacrifice in Zhenkongjiao

The Zhenkongjiao distinguishes itself from other Chinese religious traditions, which typically prioritise the preservation of animal lives as an expression of compassion, by incorporating animal sacrifice into its rituals. These sacrifices are integral to the salvation of its devotees, with rituals such as the “releasing of flowers” or “sacrificing animals to honour the way” believed to alleviate this-worldly illnesses and misfortunes. Larger “flowers” refer to animals like pigs and sheep, while smaller ones include chickens.

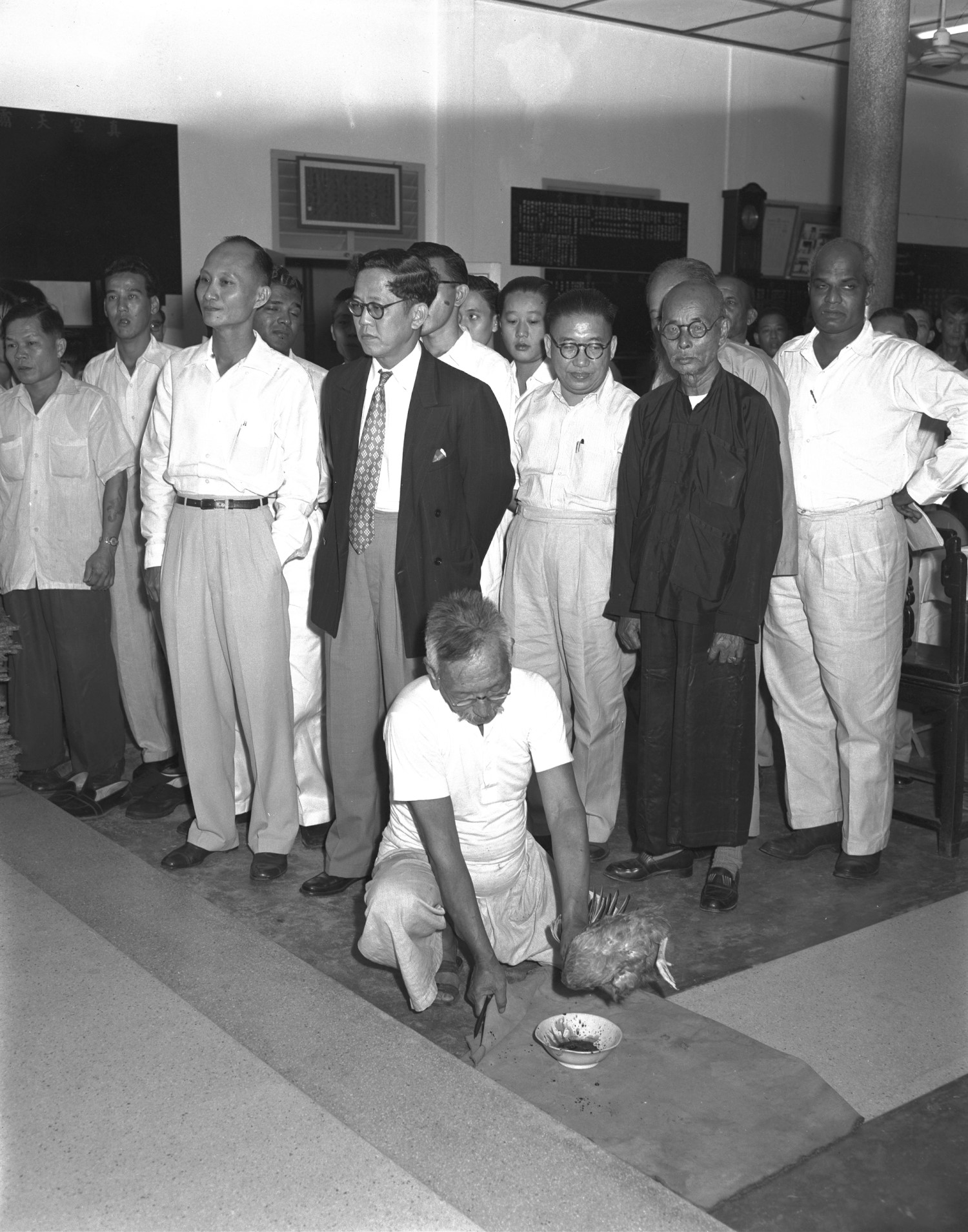

The ritual, developed by Zhenkongjiao’s founder Liao Dipin, is intended to address physical ailments, provide blessings and express gratitude. Within the movement’s cosmology, animal souls are believed to take on the karmic burdens, illnesses and misfortunes of their sponsors through their ritual offering. This act is seen as bringing relief and improvement to the sponsors’ lives in exchange for the animals’ own. Through the invocation and spiritual intervention of the patriarchs, the sacrificed animals’ souls are believed to transcend their current existence and achieve reincarnation into a more favourable state.24

Animal sacrifice was also a central component of the Zhenkongjiao’s historical opium treatment programmes, where addiction was addressed as both a spiritual and physical condition. In 1960, Xu Rukan, who led opium rehabilitation efforts at Ben Yuan Dao Tang Bukit Ho Swee (later merged into Poon Guan San Thoh Tong), instructed addicts to “prepare a rooster” when they came to the temple.25 This was likely part of the ritual offering, symbolically transferring the spiritual and physical taint of addiction to the animal. By participating in this ritual, addicts sought to rid themselves of their addiction’s burdens, supported by the sacrificial act. While such practices persisted in Singapore until 2003, they ceased following stricter livestock management regulations introduced after the SARS outbreak. However, these rituals are still practised in Malaysia. 26

Interestingly, the concept of sacrificial transference mirrors the lives of Zhenkongjiao’s patriarchs, who are described in hagiographies as embodying self-sacrifice for the benefit of their devotees. When followers petitioned the patriarchs for good health, their burdens were believed to be absorbed and taken on by the patriarchs themselves, often resulting in immense personal suffering. This practice, known as “crossing the way”, involved enduring prolonged illness and hardship as a means of alleviating the physical and spiritual burdens of their devotees.27

Chief Minister of Singapore Lim Yew Hock with guests and teachers of the Opium Addicts’ Treatment Association Singapore at a special thanksgiving service at Thian Ling Chong Toh Tong Temple at 5½ milestone Changi Road. A man prepares a chicken for ritual sacrifice, 1956. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Chief Minister of Singapore Lim Yew Hock with guests and teachers of the Opium Addicts’ Treatment Association Singapore at a special thanksgiving service at Thian Ling Chong Toh Tong Temple at 5½ milestone Changi Road. A man prepares a chicken for ritual sacrifice, 1956. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Beyond Treating Opium Addiction

The movement also recognised the need to address other illnesses among its followers. A commentary in Supplementary Histories in 1965 considered the efficacy of their methods in appealing to an increasingly educated and modern-minded audience in the long run. It argued that the movement’s approaches were too simplistic, especially considering the advancements in medical and cultural understanding.28

In 1976, in the wake of the Anti-Yellow Culture Campaign, the Zhenkongjiao Federation of Singapore publicly expressed its support for the government’s campaign against drug abuse.29 They emphasised their past efforts in helping opium addicts and highlighted plans dating back to 1974, including ones for orphan care, nursing homes and fundraising for a drug rehabilitation centre. Individuals grappling with drug addiction could seek sanctuary in Zhenkongjiao temples and stay there temporarily under the supervision of temple masters and caretakers.30 They proposed adaptations to their addiction treatment methods to address rising recreational drug use among younger Singaporeans.31

Despite efforts to move towards drug rehabilitation, the Zhenkongjiao’s endeavours in this area did not bear fruit in the long run. Following Singapore’s independence, the state and the Central Narcotics Bureau (CNB), including rehabilitation centres and law enforcement, adopted a strict zero-tolerance stance towards drug abuse, which proved more effective than the Zhenkongjiao’s rehabilitation programmes.32

Zhenkongjiao in the 1970s

The number of Zhenkongjiao temples in Singapore has fallen since 1970. Many of the temples had to make way for nation-building projects, infrastructure and public amenities. Some temples pooled resources to combine their temple facilities, such as Thian Ling Toh Tong (now part of Hock Thong Combined Temple in Bukit Batok) and Fook Poon Tong (part of Chong Pang Combined Temple).33 Others relocated to Malaysia or merged, as seen in the cases of Lingxiao and Zhenhe Daotang temples, which both merged and relocated to Johor.34 According to one estimate, only 11 Zhenkongjiao temples were in Singapore by 1998.35

One of the oldest Zhenkongjiao altars in Singapore, the Fubenyuan Daotang, is currently housed in a private residence, 2023. Photograph by Esmond Soh.

One of the oldest Zhenkongjiao altars in Singapore, the Fubenyuan Daotang, is currently housed in a private residence, 2023. Photograph by Esmond Soh.The Zhenkongjiao persisted in its secular and charitable initiatives, which were overseen by the Zhenkongjiao Federations. Various Zhenkongjiao institutions and temples in the region came together to fund the construction of Tianling Nursing Home (completed in 1989) behind Thian Ling Chong Toh Tong temple.36 Zhenkongjiao temples also frequently functioned as shelters and support centres for the elderly and those without family. In 1983, Member of Parliament Hwang Soo Jin commended Lingguang Daotang temple in Amoy Quee for providing housing for the elderly who did not have family. That same year, Zhuo Jincai, chairman of the Singapore Federation of the Zhenkongjiao, announced plans to equip the renovated Poon Guan San Toh Tong with similar facilities, besides establishing a centre for drug rehabilitation.37

Ling Kuang Toh Tong closed after their land lease expired. Their ancestral tablets were moved to Hean Thuan Toh Tong at 89 Tampines Link. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Ling Kuang Toh Tong closed after their land lease expired. Their ancestral tablets were moved to Hean Thuan Toh Tong at 89 Tampines Link. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Additionally, Thian Ling Toh Tong, then located in Mandai, was a crucial centre for the care of the intellectually disabled and abandoned children since the 1970s. In 1990, the oldest resident under the temple’s care was 60 years old, and 20 children called the temple home.38

The Zhenkongjiao also responded to significant events and tragedies in Singapore. On 12 October 1978, an explosion onboard the Greek oil tanker S.T. Spyros (docked at Jurong shipyard) resulted in what was described as the “most tragic disaster since the end of World War II” in terms of lives lost.39 The Zhenkongjiao was a crucial support for affected families, holding a three-day ritual for the souls of the deceased, with expenses covered by Thian Ling Chong Toh Tong temple. Rituals to offer spiritual solace to the deceased were also organised, including a ceremony known as the “showering of holy rain and sweet dew”.40

Moving Towards the Future

Although Zhenkongjiao temples no longer run drug rehabilitation programmes today, they remain significant centres for religious practice. Apart from observing traditional Chinese festivals like Qing Ming (tomb sweeping) and the Seventh Lunar Month, they also commemorate the birthdays of their five patriarchs. These elaborate celebrations include the recitation of the movement’s religious texts from morning to afternoon. The culmination of each event is marked by the “Repayment of Gratitude”, a solemn ceremony where believers express their appreciation to various elements of existence, including the state, family and their own good fortune. A highlight of this ceremony is the presentation of the “Five Mountains and Five Seas”, a lavish array of meat and seafood dishes, symbolising profound gratitude.41 The dishes are blessed and shared with devotees and participants to symbolise sharing the grace of the Zhenkongjiao’s patriarchs.

Rituals performed by the specialists of Thian Ling Toh Tong temple at Poon Guan San Thoh Tong’s Seventh Lunar month observation, 2023. Photograph by Esmond Soh.

Rituals performed by the specialists of Thian Ling Toh Tong temple at Poon Guan San Thoh Tong’s Seventh Lunar month observation, 2023. Photograph by Esmond Soh. Meat offerings of the "Five Mountains and Five Seas" prepared and offered to Zhenkongjiao's five patriarchs ahead of the "Repayment of Gratitude" ceremony by devotees of the Chin Kong Religion Fook Poon Tong temple, 2022. Photograph by Esmond Soh.

Meat offerings of the "Five Mountains and Five Seas" prepared and offered to Zhenkongjiao's five patriarchs ahead of the "Repayment of Gratitude" ceremony by devotees of the Chin Kong Religion Fook Poon Tong temple, 2022. Photograph by Esmond Soh.Today, Zhenkongjiao temples in Singapore continue to offer healing services to those in need. Some temples, such as Fook Poon Tong and Poon Guan Sam Thoh Tong, provide weekend meditation and scripture-reciting classes, reflecting a shift towards promoting health and mental discipline. The scriptures, meditational techniques and cosmology of Zhenkongjiao have been reworked to meet modern needs such as stress relief, mental wellness and spiritual fulfilment.42 To increase awareness of its ideals, the movement has produced easy-to-read materials aimed at a broader audience, and regularly organises lectures by Zhenkongjiao leaders.43 Although their numbers have diminished, the leaders of the remaining temples continue to adapt their practices and teachings to remain meaningful and accessible in contemporary Singapore.

Esmond Soh is pursuing his PhD with the Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Cambridge. He holds a Master of Arts from the School of Humanities at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, where he was also a lecturer following the completion of his studies.

Esmond Soh is pursuing his PhD with the Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Cambridge. He holds a Master of Arts from the School of Humanities at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, where he was also a lecturer following the completion of his studies.Notes

-

Xu Yunqiao 许云樵, “Kongdaojiao gailun: yi ge xinxing de zongjiao” 空道教概论:一个新兴的宗教 [The religion of the void: A new religion], Nanyang Xuebao 南洋学报 [Journal of the South Seas Society] 10, no. 4 (1954): 25–32. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.005 JSSS) ↩

-

Luo Xianglin 罗香林, Liuxing yu ganminyue ji malaixiya zhi Zhenkongjiao 流行于赣闽粤及马来西亚之真空教 [The Origins and Spread of the Zhenkongjiao from Ganzhou to Southeast China and Malaya] (Xianggang 香港: Zhongguo Xueshe 中国学社, 1962), 39–64. ↩

-

Esmond Chuah Meng Soh, “Practicing Salvation: Meat-Eating, Martyrdom, and Sacrifice as Religious Ideals in the Zhenkongjiao,” Journal of Chinese Religions 50, no. 1 (2022): 77–114, https://www.academia.edu/80038178/Practicing_Salvation_Meat_Eating_Martyrdom_and_Sacrifice_as_Religious_Ideals_in_the_Zhenkongjiao. ↩

-

For general studies of the phenomenon, see Yan Qinghuang, A Social History of the Chinese in Singapore and Malaya: 1800-1911 (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1986). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING301.45195105957); and Wang Gungwu, China and the Chinese Overseas (Singapore: Eastern Universities Press, 1991–2003). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING909.04951). ↩

-

Liao Jingcai 廖经才, comp., Dong nan Ya zhen kong jiao dao tang tu kan 东南亚真空教道堂图刊 [Southeast Asian Illustrated Magazine of the Zhenkongjiao Temples] (Xianggang 香港 : Zhenkong Ji Nian Tang Chubanshe 真空纪念堂出版社, 1968), unpaginated. (From National Library, Singapore, call no.: 299.514 LJC -[HYT]). ↩

-

Huang Ziwen 黄子文, comp. Kongzhongjiao Fazhan Shilue 空中教发展史略 [Supplementary Histories of the Kongzhongjiao] (Yibao 怡宝: Pili Kongzhong Jiao Hui 霹雳空中教会, 1965), 38. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. 299.51 HTW) ↩

-

For an introduction to the lives and religious careers of these individuals, see Shi Cangjin 石沧金, Hai wai Hua ren min jian zong jiao xin yang yan jiu 海外华人民间宗教信仰研究 [Overseas Chinese folk religion research] (Kuala Lumpur: Xuelin Shuju 学林书局, 2014), 44-48. (From National Library, Singapore, call no.: 299.51 SCJ). ↩

-

Xinjiapo zhen kong jiao lian he hui ji ben yuan shan dao tang xin sha luo cheng kai mu ji nian ce 新加坡真空教联合会暨本元山道堂新厦落成开幕纪念册 (Xinjiapo 新加坡: Xinjiapo Zhenkongjiao Lian He Hui 新加坡真空教联合会, 1992), 126. (From PublicationSG, call no. 299.51) ↩

-

Shi Cangjin 石沧金 and Ouyang Banyi 欧阳班铱, “Xinjiapo Zhenkongjiao fazhanshi chutan 新加坡真空教发展史初探 [A Preliminary Study of the History of Zhenkong Religion in Singapore],” Huaren yanjiu guoji xuebao 华人研究国际学报 [International Journal of Diasporic Chinese Studies] 4, no. 2 (2012): 92. ↩

-

One of the classical studies include Lionel Robbins, The Great Depression (Freeport, N.Y.: Books for Libraries Press, 1971) (From National Library, Singapore, call no. 330.904 ROB). ↩

-

Loh Kah Seng, “Beyond Rubber Prices: Negotiating the Great Depression in Singapore,” South East Asia Research 14, no. 1 (2006): 5–31 (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website); and W. G. Huff, “Entitlements, Destitution, and Emigration in the 1930s Singapore Great Depression,” The Economic History Review 54, no. 2 (2001): 290–323. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Shi and Ouyang, “Xinjiapo Zhenkongjiao fazhanshi chutan,” 92-93. ↩

-

“Suppressing Opium Smoking,” Straits Times, 4 February 1946, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Huang, Kongzhongjiao Fazhan Shilue, 34. ↩

-

“Doctors Debunk Prayer Cures,” Singapore Standard, August 14, 1952, 2; Lim Siew Kok, “‘Debunkers’ Challenged,” Singapore Standard, August 25, 1952, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Court Upset by Woman,” Straits Times, June 13, 1956, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Dope Faith Men Get Promise from Mr. Lim,” Straits Times September 23, 1956, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Cures with a Tea!“ Singapore Free Press, May 11, 1956, 14. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

William Fish, “Opium—A Temple of Hope,” Straits Times, 6 March 1956, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Some Odd Corners & Customs of Malaya,” Sunday Tribune, 6 August 1933, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Temple Ruse by Opium Addicts is Denied,” Straits Times, 1 July 1956, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Soh, “Practicing Salvation,” 100-107. ↩

-

“眞空敎本元道堂實行義務戒煙 [The Zhenkongjiao Ben Yuan Dao Tang Implements Free Smoking Cessation],” Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 15 March 1960, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

谭文熙 Tham Wen Xi, 新加坡宗教个案研究: 新加坡真空教在近年的发展 [A Case Study of Singapore Religion: The Development of Chin Kong Religion in Singapore] (Hons. Thesis, Department of Chinese Studies, National University of Singapore, 2011), 48–49. ↩

-

Soh, “Practicing Salvation,” 105–107. ↩

-

Huang, Kongzhongjiao Fazhan Shilue, 72-75. ↩

-

Seow Peck Ngiam, “Anti-yellow Culture Campaign,” Singapore Infopedia. ↩

-

Xingzhou zhen kong jiao lian he hui cheng li nian er zhou nian ji nian te kan 星洲真空教联合会成立廿二周年纪念特刊 [Commemorative Volume Marking the 20th Anniversary of the Federation of the Zhenkongjiao in Singapore]. Singapore: Federation of the Zhenkongjiao in Singapore (Xin jia po: 星洲真空教联合会 Xingzhou Zhenkongjiao lian he hui, 1976), 1-8. (From National Library, Singapore, call no.: 294.39 SEN) ↩

-

“Kongjiao lianhehui qingzhu Zhenkong zushi danchen choujian huishi zuowei jiedu zhongxin 眞空敎聯合會慶祝眞空祖師誕辰籌建會所作爲戒毒中心 [The Zhenkongjiao Association celebrates the birthday of Zhenkong Patriarch by raising funds to establish a center for drug rehabilitation],” Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 11 May 1976, 17. (From NewspaperSG); “Kongjiao lianhe hui zutuan jin qicheng fangwen gedi yanjiu you xiao jiedu fa 眞空敎聯合會組團今启程访问各地研究有効戒毒法 [The Zhenkongjiao Association organizes a group to embark on visits to various places to research effective methods of drug rehabilitation],” Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 7 January 1977, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Ng Ser Song, “Toward a Drug-Free Society: The Singapore Approach,” Brown Journal of World Affairs 26 (2019-20): 245–252. ↩

-

Hue Guan Thye, “The Evolution of the Singapore United Temple: The Transformation of Chinese Temples in the Chinese Southern Diaspora,” Chinese Southern Diaspora Studies 5 (2012): 157–174. ↩

-

Shi and Ouyang, “Xinjiapo Zhenkongjiao fazhanshi chutan,” 98. ↩

-

Shi and Ouyang, “Xinjiapo Zhenkongjiao fazhanshi chutan,” 94. ↩

-

“Tianling Laoren Yuan jianjun 天灵老人院建竣 [Completion of Tianling Elderly Home],” Lianhe Wanbao 联合晚报, 24 November 24 1989, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Zhenkongjiao lingguang daotang jiaozhu shengdan Huang Shuren zan gai tang fuwu jingshen peihe shehui xuyao zuochu gongxian真空教灵光道堂教主圣诞 黄树⼈赞该 堂服务精神 配合社会需求作出贡献 [The celebration of the birthday of the spiritual leader of the Lingguang Temple of the Zhenkongjiao, praised by Huang Shuren for the spirit of service of the temple, contributing to the needs of society],” Lianhe Wanbao 联合晚报, 28 May 1983, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Baichi zhi jia Tangshen you dao tang shouyang ershi ren 白痴之家汤申有道堂收养二十人 [Thompson Road Temple is Home to 20 Intellectually disabled people],” Lianhe Wanbao 联合晚报, 12 February 1990, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Gillian Pow Chong, “Singapore’s History Book of Disasters,” Straits Times, 17 January 1984, 15. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Xingma zhen ma Zhenkongjiao lian he ding qi wei you chuan li nan zhe ju xing chao jian fa hui 星马眞空敎联合订期 为油船罹难者 举 ⾏超荐法会 [The Singapore-Malaysia Zhenkongjiao Alliance schedules a memorial service for the victims of the oil tanker accident],” Sin Chew Jit Poh 星洲⽇報, 5 November 1978, 30. (From NewspaperSG); “Xingma Zhenkongjiao ge dao tang wei can huo li nan zhe zhu ban chao jian fa hui 星马眞空敎各道堂 为惨祸罹难者 主办 超荐法会 [Various Zhenkongjiao temples in Singapore and Malaysia host memorial services for the victims of the tragic accident],” Sin Chew Jit Poh 星洲⽇報, 25 November 1978, 10 (From NewspaperSG); “Zhenkongjiao Tian Ling Zong Dao Tang lian he Xinma liangdi daotang wei chuan nan si zhe juxing chao jian fahui ji gong ji 真空教天灵总道堂联合新⻢两地道堂为船难死者举行超荐法会及公祭 [The Zhenkongjiao Tian Ling Zong Daotang, in conjunction with temples in Singapore and Malaysia, holds memorial services and public ceremonies for the victims of the maritime disaster],” Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 25 November 1978, 39. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Esmond Chuah Meng Soh, “Article Sneak Peeks: May 2022,” Society for the Study of Chinese Religions, last accessed 20 April 2024. ↩

-

Esmond Chuah Meng Soh, “Sectarians, Smokers, and Science: The Zhenkongjiao in Malaysia and Singapore,” Asian Ethnology 81, no. 1/2 (2022): 35-42. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

黄嘉伟 Huang Jia Wei,《空道流行》入微 “Kong dao liu xing” ru wei [Delving into the Way of Emptiness] (Xinjiapo 新加坡: Xinjiapo Zhenkongjiao Lian He Hui 新加坡真空教联合会, 2016) (From PublicationSG, call no. 299.51) ↩