This is My Story: Autobiographies and Biographies As Research Resources for Chinese Diasporas

Written records in the form of autobiographies and biographies allow us to gain an understanding of the cultural, socio-political and economic conditions as well as the lives and backgrounds of personalities from the past.

Throughout history, man has recorded his interpretations of the world around him. This can be seen from early cave drawings to the published written life of a person . Written records in the form of autobiographies and biographies have enabled readers to gain an understanding of cultural, socio-political, and economic conditions, and the personal lives and backgrounds of people in a particular time frame. This helps to add dimensions to the official records compiled by historians. The writer of official historical records has to decipher and select information that best represent the priorities of the writer’s life and time. In the process of doing so, we often only get to see the ‘big’ picture or sometimes the officially recognised picture, but not the other side of the story that will help enrich our understanding of the life and times of people in a particular phase in history.

Hence, autobiographies and biographies involve a narration of self-identity in relation to life experiences, usually told retrospectively and often in a chronological order. For the autobiographer, it is dependent on his memory, his interpretation of his surroundings, as well as his values and attitudes towards life. For writers of biographies, there is an added challenge of piecing together the information gathered from a myriad of sources.

An important value in an autobiography is the fact that it allows the reader to get into the inner world of the writer and have a glimpse of the life he constructed and believed. This offers great research values to those who are looking for information on the political, social and economic conditions of a certain era. For instance, in Ho Rih Hwa’s Eating Salt: An Autobiography, he relates about his conflicting emotions regarding his self-identity when Singapore became independent. He mentions that his feelings of “patriotism bursting from within but no country to be patriotic to” was changed to “an overwhelming joy … I finally had a nation to which I could feel I truly belonged, and it was up to me and to my fellow countrymen to make the independence a lasting one”. In this particular instance, it gives the reader a sense of how a second generation Chinese Singaporean felt during that historic moment.

The presentation of one’s life story in a literary form implies that there is a choice in the language, ways of narration and layout of ideas.

According to Ira Bruce Nadel, factual biography “depends as heavily on conceptual paradigms and narrative patterns as fiction”. Therefore, there is a tendency to select facts and details that will support the claims of the writer. In other words, the writer will tend to create a picture through language to influence his readers’ impressions, images and interpretations. To write an objective biography, according to Nadel, is “logically and artistically impossible”. He explains that observation often involves a selection of “a chosen object, a definite task, an interest, a point of view, a problem”, in order to make sense of what the writer is trying to convey to his readers. Similarly for autobiographies, the personality and world-view of the autobiographer very much dictates how he describes his life. Hence, the researcher will have to exercise caution when making use of autobiographies and biographies as resources.

There are various considerations to bear in mind when reading a biographical account. It is a complex narration of an individual’s life and it can be seen as a literary work or a historical product. While weighing the pros and cons of autobiographical or biographical accounts, they still form an essential part of understanding the Chinese diaspora experience. Depending on the purpose of reading the autobiographical and biographical works, the treatment and analysis of these accounts may differ according to information content, time frame, literary style and the intended audience of the writer. It will be the researcher’s responsibility to authenticate the facts supplied by the writer and to analyse the accounts with support from various other sources in order to validate the information provided in the autobiographical and biographical works.

The Lee Kong Chian Reference Library’s Singapore and Southeast Asian Collections has a collection of autobiographies and biographies of prominent Chinese Singaporeans. One of the earliest publications comes from Song Ong Siang’s One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore, published in 1923. Song is an example of the few privileged Straits Chinese in the early days to obtain higher education overseas and who was eager to contribute to society. Song was a fourth-generation Straits Chinese whose family came from Malacca . A Queen’s scholar, he attended Downing College of Cambridge University where he was its first Chinese graduate. Upon his return to Singapore, he became a lawyer and focused his energy on serving Singapore. He nurtured and promoted women’s education and served on the legislative council, advancing local rights and interests. His loyalty and service to the crown later earned him a knighthood from the British Empire.

His One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore, written in a narrative style, is presented in a chronological format that traces the social lives, trials and tribulations, and fortune building of the Chinese community from 6 February 1819 to 6 February 1919. It also includes sections on individual prominent Chinese and illustrations of them. Another important information resource on the early Chinese diaspora in Singapore is the Biographies of Prominent Chinese in Singapore, edited by Victor Sim and published in 1950. Over 100 prominent Chinese in Singapore are featured in this bi-lingual collection of biographies, complete with a photograph of each individual. In 1984, the Archives and Oral History Department published Pioneers of Singapore, a catalogue of interviews conducted between the period of January 1980 to February 1984, with 73 prominent business pioneers (out of which 51 are Chinese). The exercise aimed to capture their recollections of past experiences to form a fabric of the social history of Singapore.

Chinese Pioneers

One outstanding early Chinese diaspora was Aw Boon Haw. Aw Boon Haw was born to a Chinese herbalist, Aw Chu Kin in 1882 in Rangoon, while his younger brother Boon Par was born in 1888. Although his name meant “gentle tiger”, the young Boon Haw was quite the opposite. He played truant from school constantly, and was eventually expelled. He was sent back to his family’s ancestral village in China’s Fujian province, leaving Boon Par to run his father’s medicine shop.

After the demise of his father, Boon Haw returned to Rangoon and managed the business, while Boon Par apprenticed himself to a local pharmacist, UThaw. Prior to his death, UThaw bequeathed a secret recipe for a pain-relieving ointment to Boon Par. The two Aw brothers perfected this recipe, and christened the new concoction Ban Kim Ewe (Ten Thousand Golden Oil), a remedy for all maladies.

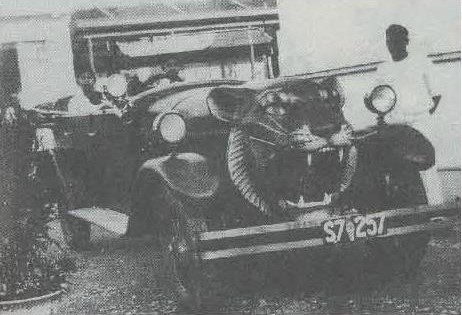

A “genius in promotion, advertising and marketing”, Boon Haw made used of his ethnic Hakka ties to sell Ban Kim Ewe to local Chinese medicine shops, and business expanded rapidly to Southeast Asia by the late 1920s. Boon Haw devised ingenious methods of promoting his product, and even built a tiger-shaped car from which he distributed enameled posters of the products.

In 1926, Boon Haw moved to Singapore and started up shop in a two-storey shophouse in Amoy Street. Soon, Singapore became the base for his business in Malaya and the East Indies.

Besides being an astute businessman, Boon Haw also founded Sin Chew Jit Poh in Singapore, the first of a group of newspapers in the region, only three years after setting up business here. This was followed by Chinese-and English-language papers in Hong Kong, Taiwan and Thailand.

The life and times of Aw Boon Haw is captured vividly in the biography Tiger Balm King. The author conducted interviews with his family members who provided information about Aw Boon Haw’s personal life.

In From Chinese Villager to Singapore Tycoon: My Life Story, LienYing Chow shared his from rags to riches success story. It serves as an example of the route many Chinese took to seek their fortunes in the Southeast Asian region. Lien Ying Chow arrived in Singapore with only a few dollars in his pocket. Being an entrepreneur, he established the Overseas Chinese Union Bank in China, and later opened the Overseas Union Bank (OUB) in Singapore.

Another prominent Chinese pioneer is Tan Kah Kee. His memoirs, Nan Qiao Hui Yi Lu, which was written in 1946 was translated into English - The Memoirs of Tan Kah Kee in 1994. Originally from the village of Jimei, China, Tan Kah Kee arrived in Singapore at age 16 (1890) to work in his father’s rice store. The business collapsed in 1903, but Tan Kah Kee went on to build an industrial empire ranging from rubber plantations and manufacturing, sawmills, canneries, real estate, import and export brokerage, ocean transport to rice trading. The years between 1912 and 1914 were the best for his enterprises when he amassed a huge fortune. He came to be known as the “Henry Ford of Malaya”.

Spending his fortune not on himself or his family, but the community, Tan Kah Kee was a philanthropist. His abiding concerning was education. He founded and financed several schools and other educational institutions in his native homeland as well as in Singapore. Among the schools he founded in Singapore are Singapore Chinese High, Tao Nan, Ai Tong, Chong Fu, and Nanyang Girls’ High.

Tan Kah Kee was also a well-respected community leader. Active in campaigning for educational and social reforms in the 1920s and 1930s, he was twice chairman of the Chinese Chamber of Commerce and helped to re-organise the Hokkien Clan Association. In 1923, he launched the Chinese newspaper, Nanyang Siang Pau. In addition, he was active in organising various relief funds for China during the Japanese invasion.

Tan Kah Kee began writing his memoirs while taking refuge in Java from the Japanese. From his memoirs one could see that he placed more importance on his involvement in education, social reform and politics than on his business undertakings. It is regarded as “one of the best documented autobiographies ever written by an immigrant Chinese in South-east Asia … an immensely important source for those seeking to understand not onlyTan Kah Kee himself but the Chinese community in Singapore and Chinese politics as a whole”.

Materials Available

The autobiographies and biographies available in the library can be divided into the following general categories: artists, bankers and entrepreneurs, early Chinese immigrants, educators, political personalities, ex-prisoners of war, and the Straits Chinese.

In conclusion, autobiographies and biographies form an interesting description of personal experiences and contributions of individuals to the society through the years. The photographs and snippets of information offer researchers a rich information resource to discover and elaborate on. Thus, the collection of life stories gets to be enriched and preserved.

Senior Reference Librarian

Lee Kong Chian Reference Library.

FURTHER READING

Alan Chong, Goh Chok Tong, Singapore’s New Premier (Malaysia: Pelanduk Publications (M), 1991). (Call no. RSING 959.57092 CHO)

Archives & Oral History Department, Singapore, Pioneers of Singapore: A Catalogue of Oral History Interviews (Singapore: Archives & Oral History Department, 1984). (Call no. RSING 016.9595700992 SIN)

Grace Loh and Lee Su Yin, Beyond Silken Robes: Profiles of Selected Chinese Entrepreneurs in Singapore (Singapore: Times Academic Press, 1998). (Call no. RSING 338.040922595 LOH)

Lee Kuan Yew, From Third World to First: The Singapore Story, 1965–2000: Memoirs of Lee Kuan Yew (Singapore: Times Editions: Singapore Press Holdings, 2000). (Call no. RSING 95957092 LEE)

Sheila Allan, Diary of a Girl in Changi, 1941–45 (N.S.W.: Kangaroo Press, 2004). (Call no. RSING 940.547252092 ALL)

Wee Kim Wee, Wee Kim Wee: Glimpses and Reflections (Singapore: Landmark Books, 2004). (Call no. RSING 9595705092 WEE)

Zhou Mei, Elizabeth Choy: More Than a War Heroine: A Biography (Singapore: Landmark Books, 1995). (Call no. RSING 37110092 ZHO)