Monument of Memory and More: The History of Victoria Street

Provides a quick-potted history of Victoria Street, including the site currently occupied by the National Library Building.

“There are places I’ll remember

All my life though some have changed …

… AII these places have their moments

With lovers and friends I still can recall

Some are dead and some are living

In my life I’ve loved them all”

Lyric extracts of Lennon/McCartney’s “The Beatles’ IN MY LIFE”

In 1999, a Straits Times headlines, “National Library to go” announced that the familiar red-brick building along Stamford Road would soon make way for new developments. Despite much protest from the public who had grown to love the building, the library needed to move to a new site to keep up with the times, especially as information needs were expected to move by quantum leaps in the 21st century.

History

Formally established in 1845, the Singapore Library carried fiction and non-fiction books and included a Reference section. In 1874, it became a government institution known as the Raffles Library and Museum, and was located at Stamford Road at what is today the National Museum’s building. In 1955, it was separated from the National Museum, and eventually in 1960, the library moved into its own building next door.

(Center) The Junior Library of the Raffles Library in the 1950s.

(Right) The Raffles Library display in the Community Education Exhibition, 1957.

In 1953, millionaire philanthropist Dr Lee Kong Chian, made a donation of $375,000 “towards the foundation of a public library with the condition that it house books in Asian languages that would be fully representative of the cultures of Singapore.” The former St Andrew’s School buildings occupied by the British Council was vacated, as the land was developed for the “ Raffles Library.”

The completion of the library building at Stamford Road was met with shocked reactions from architects and academics alike. They remarked that the architecture was “too severe” “intimidating”, “forbidding”, and “heavy looking”. In a Free Press newspaper article dated 9 July 1960, entitled, “They gasp with horror at this ‘monstrous monument’’’, William Lim, a representative of a new generation of local architects, described the $2 million structure as ‘a complete and absolute failure of the architect to create the necessary atmosphere and delight.” The PWD Architect clarified that the design was more contemporary in style but would consider improvements. On 12 November 1960, the new building was officially opened by President Yusof Ishak, and the library was renamed the National Library of Singapore.

Despite the initial unfavourable comments about the “red-brick balustrade” building, it eventually endeared itself to the public, as it fulfilled not only the requirements of researchers but quickly became a popular hangout for generations of Singaporeans.

On 1 April 1997, the building was closed for ten months for extensive renovations and upgrading. When it reopened to the public on 16 January 1998, it offered a wider range of collections and services. Through the legal deposit (a regulation where publishers must deposit two copies of all Singaporean publications with the National Library Board at their own expense within four weeks of publication), publications on Singapore and by Singaporeans had increased. The newly renovated Reference Section could thus showcase a strong collection on Singapore. The famed Southeast Asia Room that had drawn many researchers to the National Library since it opened in 1964 was given free access to all. Yet, even with the renovations, it quickly became obvious that the space for the collections remained insufficient.

When the National Library Board was told that the building would be affected by a proposed traffic tunnel and must be relocated, there was a huge public outcry.

Strong sentiments appealed for the preservation of the building. Many recalled the treasured memories they had of the landmark building. A generation of Singaporeans had grown up borrowing books here, and consuming refreshments at the ‘tin-shed’ coffee shop. A member of public complained that the sacred building had to be “gouged out to make way for the opening of a traffic tunnel”.

This distinct red brick structure though initially condemned, stood at Stamford Road for 44 memorable years and served the needs of the people until 31 March 2004 when the National Library closed its doors. The building was demolished shortly after, and readers had to use the other branch libraries.

The New Victoria Site

On 4 June 2001, the Singapore Land Authority issued a 60 years lease No 24897, with land of a gross plot ratio of 5.2 in accordance with the plans approved by the competent authority under the Planning Act (Cap 232), for the development of the Nation’s main Library Institution. The groundbreaking ceremony was held at this site on 30 October 2001.

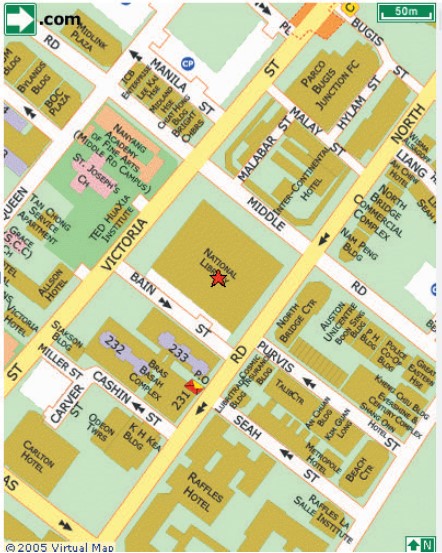

The National Library is situated at 100 Victoria Street and is gradually becoming a landmark of the Bugis/Bras Brasah area. Even as the National Library creates a new beginning at Victoria Street, it is appropriate to take a retrospective look at the history of Victoria Street.

History of the ‘New Site’

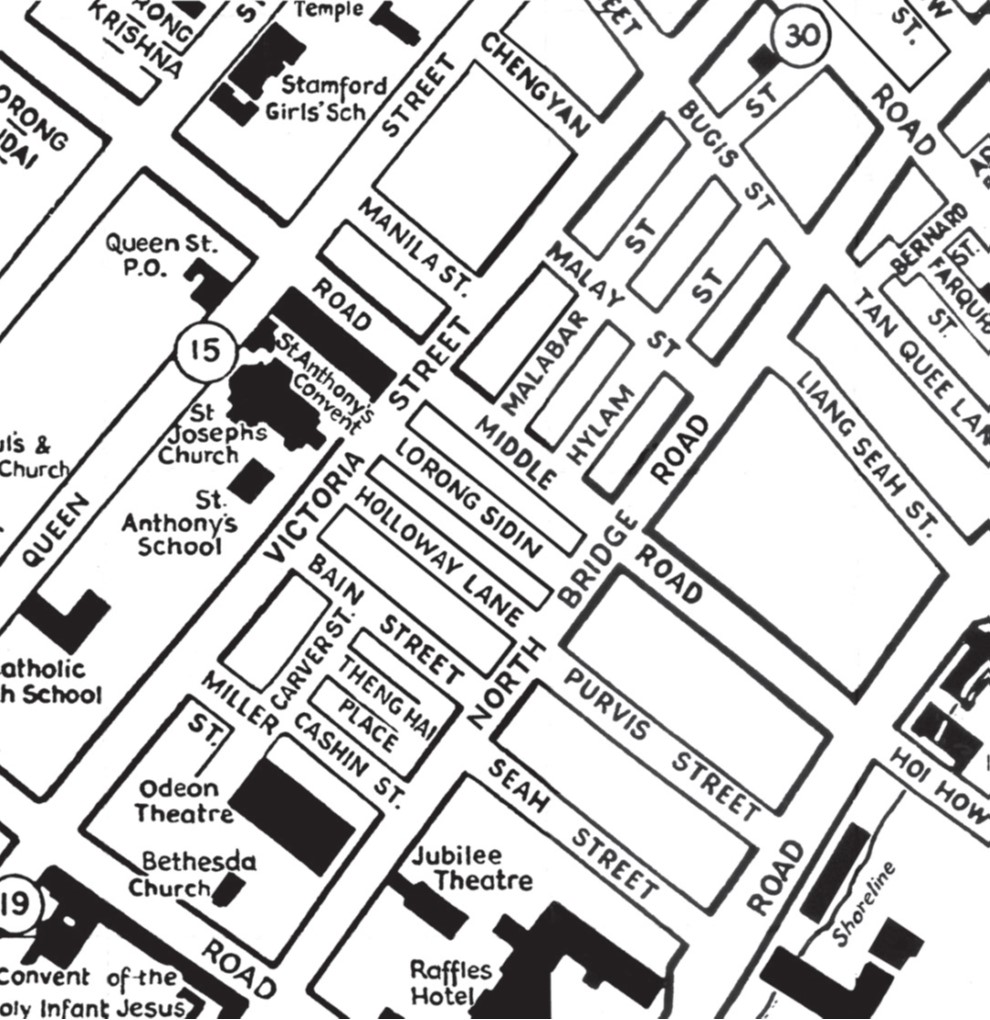

The Victoria site is today part of the Singapore town land sub-division. The land area is bounded by Victoria Street, Middle Road, North Bridge Road and Bain Street, and was once a nutmeg plantation and a betel-nut plantation. By the instructions of Sir Stamford Raffles’ ‘Town Plan’, land was leased by auction, and leases had tenure of 999 years.

Original Owner - Andrew Farquhar

A large portion of this land was formerly the private property of an enterprising merchant, Andrew Farquhar, the eldest son of the first Resident of Singapore, Colonel William Farquhar. In 1821, Andrew Farquhar aged 20, moved from Malacca to Singapore, and invested in properties. There is no record of when he actually bought the more than 2-acre site at the junction of North Bridge Road and Middle Road, opposite his father’s property and residence at Beach Road, except that lease No. 503 was issued on 20 March 1828. In June 1824, he married Elizabeth Robinson, and with their three children, they moved to the Victoria site.

In 1827, Andrew Farquhar became first appointed Coroner in Singapore but in January 1829, on a visit to Jakarta, he became seriously ill and died. In December 1830, James Scott Clark, Administrator of Andrew Farquhar’s estate sold the property to John Henry Moor, the Headmaster of the Raffles Institution. The property was probably acquired for investment, as he and his family stayed at the school. In January 1832, Elizabeth Farquhar remarried James Scott Clark, and in March 1834, J H Moor leased part of his property to her youngest son, Andrew Charles Robert Farquhar. Although the area was smaller, Farquhar’s family was still able to stay there.

The Victoria site had a nutmeg plantation and Mrs Elizabeth Clark ran a boarding house there. Andrew C R Farquhar began as a clerk at Martin Dyce & Co and Little Cursetjee & Co. On a visit to Calcutta, India, he fell in love and got married there. In May 1854 he sold his property, and left Singapore for good. When Mrs Clark’s second husband James passed on, she went to join her son in Calcutta, and in July 1867, died there.

Joseph M Cazalas’s Property

John Henry Moor’s other property at the Victoria site w as leased in October 1832 to Joseph M Cazalas, the first mechanical engineer in Singapore, and a Eurasian . It remained a betal-nut plantation until 1866, when Cazalas changed the land use and operated a metal foundry at Middle Road.

Besides managing the foundry, J M Cazalas joined the Police in 1873 and served in the Voluntary Fire Brigade. In 1879 he mortgag ed his property to Seah Eu Chin. Seah, a wealthy merchant, owned numerous nutmeg and gambier plantations. Cazalas remained at Middle Road until 1885 when he died and his family sold the property to a Chinese owner in the name of Ban Hap Kongsi.

Properties of Charles Prince Holloway

Also part of the Victoria site was Lease 262, (22.52m2 / 242,400 sq ft) owned by the 40t h Bengal Native Infantry Regiment. In April 1827, it was sold to another Eurasian, Charles Prince Holloway. As there was an access lane to his property, it was convenient to name the small road, Holloway Lane, after him. In 1846, C P Holloway was in the Deputy Registrar of Imports and Exports at the Trade Department, and in 1853, he was transferred to the Marine Department. In 1860 he moved to Prinsep Street but the name Holloway Lane remain unchanged until the land was cleared in the mid-1970s. On 23 October 1966, Prime Minister Lee KuanYew officiated at the opening of the “Kheng Ngai Lee Clan Association ‘; possibly the only distinctive organisation in this little street.

Gilbert Angus Bain’s Properties

In 1854, Charles Prince Holloway sold 5 subdivided land lots to Gilbert Angus Bain , a Eurasian from Lerwick, Shetland Islands. He came to Singapore in 1842, and first worked as a clerk, but was later made a partner in several European-owned companies, as well as Hoo Ah Kay’s Whampoa & Co. His younger brother Robert Bain worked in A L Johnston & Co . The Ba in brothers were enterprising traders, especially Gilbert Angus Bain . He owned two large properties atTanjong Pagar, one known as Bain’s Hill. When theTanjong Pagar Dockyard was constructed, he sold Bain’s Hill, and then invested in a few other properties. His name is listed in quite a few land titles at the Singapore Land Authority.

When the Singapore Library was opened in January 1845, G A Bain, an avid reader was one of the 32 subscribing shareholders. As a shareholder, he paid $30, and a monthly subscription of $2.50. He and his brother Robert continued their membership in the Raffles Library and Museum.

Between 1844 and 1860, Gilbert and Robert Bain were Jurors of the Grand Jury, and on a few occasions were also the foremen or leaders of the Jury.

Gilbert Angus Bain died in Singapore on 24 March 1887, and left a family of seven sons and two daughters.

St Joseph’s Church

In 1822, the Portuguese Catholic priests obtained from Raffles land for a small church. In the 1850s, it was considered too small for the residents especially the Eurasians living at the European quarters. In 1906, the original church was demolished, the present Church of St Joseph was built in 1912- a landmark that remains at the front of the main National Library entrance.

Street Names

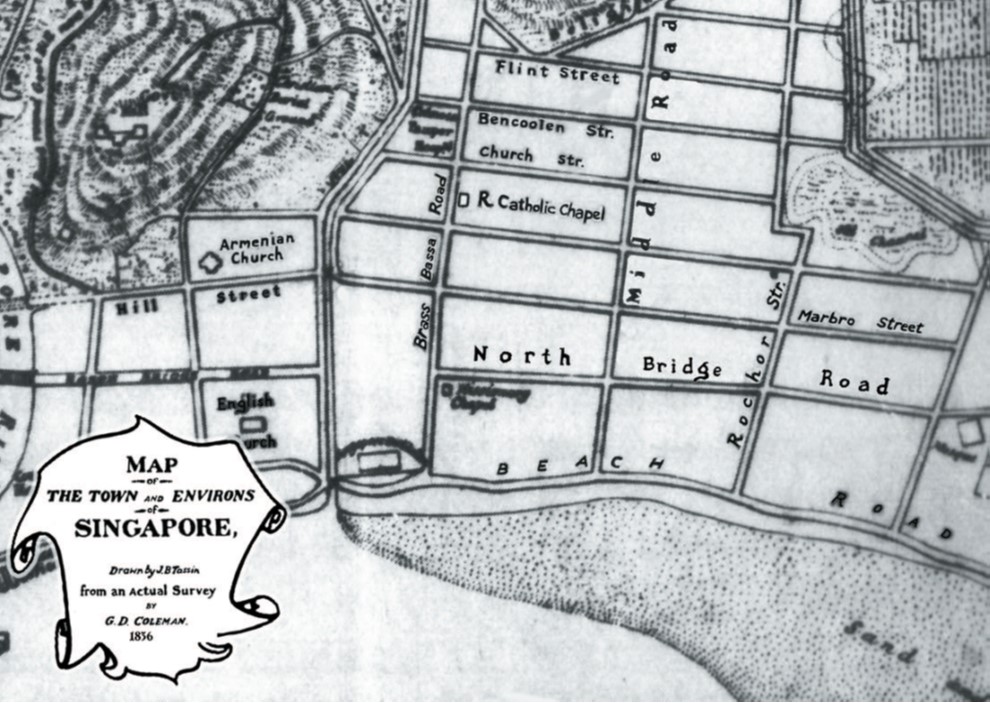

As seen in leases in which survey plans were attached, North Bridge Road and Middle Road were named in 1826 by Lieutenant Philip Jackson. George D Coleman’s 1836 town plan and map retained these names.

Coleman used the name ‘Marbro Street’; for the street parallel to North Bridge Road wherea s Jackson had earlier named it Rochor Street in his 1823 Town Plan. According to Dr John Bastin “Marbro” was an abbreviated term used in honour of the Duke of Marlborough. The name may have changed a few times in the 19th century, but in 1848, “Victoria Street” and the next street, “Queen Street” were named in honour of the much-loved Queen Victoria (1819–1901), to commemorate her 10th year reign as a British monarch.

In 1887, the Collector of Land Revenue, Land Office, Mr H T Haughton mentioned that in accordance with Section 143 of the Municipal Ordinance, the Commissioners should introduce the dialect names of places in Singapore, as in many instances, these names historically reflected the character of the place. The names of both Bain Street and Holloway Lane in the Chinese Hokkien dialect were Sek Kia Ni Lai Pai Twi Bin Hang meaning “The lane opposite the Portuguese Church” (The term Sek Kia Ni is derived from the Malay word Serani meaning “Eurasian”). The two names in Tamil Pakku Thoppu meant “Betel-nut garden”.

Building Layout of the Vicinity

In the late 19th century with increasing immigrants settling in Singapore, the town expanded . Singapore’s entrepot and change of land use resulted in intensive use of shophouses in the town. The old houses were gradua lly demolished and there were no more plantations.

In its place, shophouses of 2 to 3 storeys were built, the ground floor for shops and trades, and upper floors for residence . Roads w ere not affected by these developments, so their street names remained unchanged.

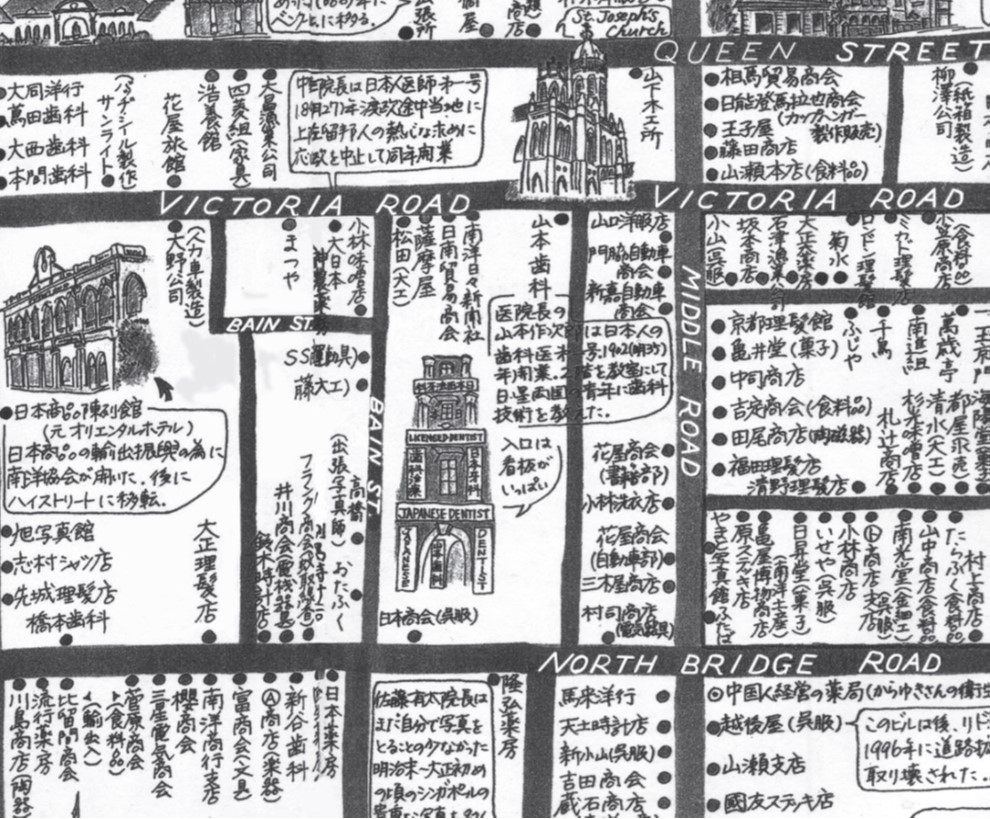

Little Japan

Japanese migrants had been in Singapore since the late 1800s until the outbreak of war in 1941.

Most of the community settled along Middle Road and the streets adjoining it north and south, and their businesses and accommodation in shophouses extended to North Bridge Road and Victoria Street.

Japanese of different professions and trades existed here. But the main concentration of their presence was at Middle Road , with their ‘town centre’ being where the Library now stands today. Business activities in the area included a well-kn own textile store Echigoya & Co., import and export traders, shoes shops, photo studios, barbers, restaurants, bars, medical and dental clinics etc. Other institutions like the Japanese Elementary School, the Japanese Association, the Japanese Club and the Japanese Consulate, were just outside this area. The Middle Road area was called Nihanjin machi (or “Japanese town”).The Chinese or Europeans usually referred to it as “ Little Japan” or “Little Tokyo”.

Just before World War II , the Japanese left and returned to Japan.

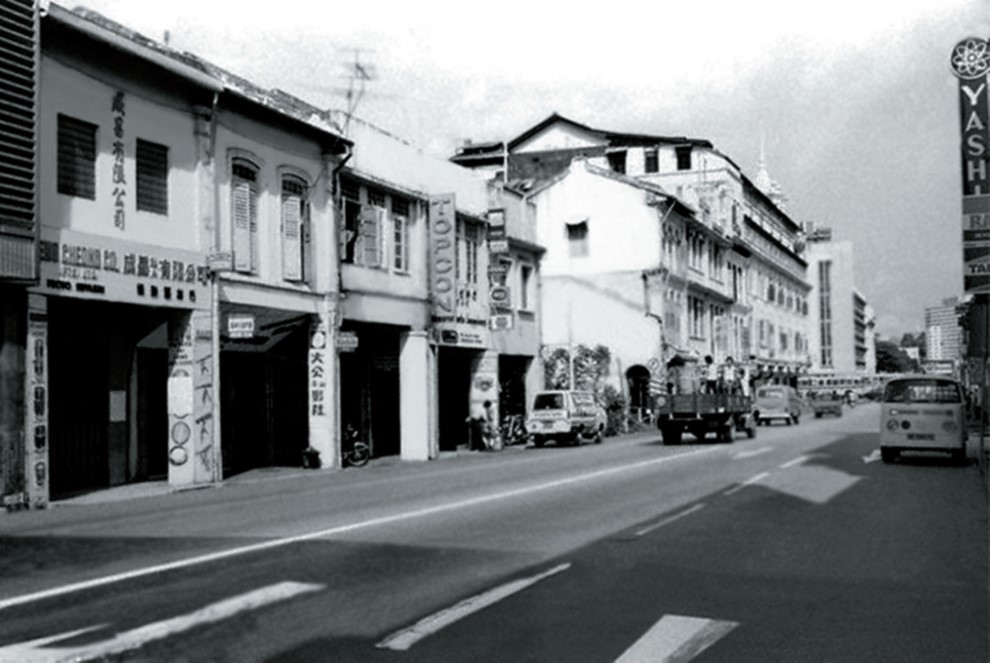

Post War Environment

After the war and until the late 1980s, as land leases expired, the area of shophouses with its business and residential characteristics generally remained unchanged. Between North Bridge Road and Victoria Street, Middle Road was well-known for its shoe shops on one end, and camera shops on the other. Victoria Street was the place for furniture, especially cane-furniture and upholstery; North Bridge Road was the place for Chinese books (Popular Bookshop, Black Cat Book Co., and Youth Bookshop), stationery and record stores, goldsmiths and jewellers, photo studios, furniture shops and other retailers. At the junction of Victoria Street and Middle Road, stood the landmark Empress Hotel. Built in 1932, with a restaurant added later in the 1950, this typical Chinese hotel attracted visitors from neighbouring countries, particularly tourists from China. For years it was famed for its delightful and delectable “moon cakes”.

Opposite the Empress Hotel was St Anthony’s Canossian Convent School, and next to it, the then Catholic Portuguese Mission of St Joseph’s Church, and on its left - St Anthony’s Boys’ School.

By the late 1980s, hundreds of buildings owned by private owners in these areas were acquired and demolished. On the National Library site were two roads, Holloway Lane and Lorong Sidin, which were expunged to make way for comprehensive redevelopment. In 1980, at Bain Street and North Bridge Road, the first inkling of modernity to the area was the Bras Basah Complex with two 25-storey blocks HDB flats.

The National Library Today and Tomorrow

A large 11.3 m2 (121,679 sq ft) site at 100 Victoria Street, the ‘new’ National Library opened its doors to the public on 22 July 2005, and was officially opened on 12 November 2005, by the President of Singapore S R Nathan.

Housing a wealth of knowledge, the new National Library is a large complex with 16 levels of floor space, abundant with local and international information resources, plus the extensive Singapore and Southeast Asian Collections of the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library.

In the years to come, this new Library, on the historical Victoria Street, will continue to be, as it did at Stamford Road, an important institution of education and entertainment, and also a ‘Monument of Memory’ for the generations to come!

Consultant

Singapore Land Authority

Edited by Vernon Cornelius.

FURTHER READING

Charles Burton Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore, 1819–1867 (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1984). (Call no. RSING 959.57 BUC-[HIS]

One of the principle sources for the study of the history of 19th century Singapore, the comprehensive volume contain a wealth of information on all aspects of British administration and society in Singapore.

Kwok Kian Woon, Ho Weng Hin and Tan Kah Lin, eds., Memories and the National Library (Singapore: Singapore Heritage Society, 2000)

Published by the Singapore Heritage Society, this title is a compilation of articles and letters that appeared in the local press over the controversial decision ,by the government to demolish the National Library building at Stamford Road.

National Archives (Singapore), Reminiscences of the Straits Settlements Through Postcards (Singapore: National Archives of Malaysia and National Archives of Singapore, 2005). (Call no. RSING 959.503 REM)

Containing more than 100 postcards, the publication takes the reader back to life in the Straits Settlements during the late 19th and early 20th century. A fascinating record of images, the book also includes supporting archival records include maps, building plans and documents.

Ole Johan Dale, Urban Planning in Singapore: The Transformation of a City (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1999). (Call no. 307.1216 DAL)

The book details the process of urban planning in Singapore by tracing its early growth on the banks of the Singapore River to its present structure. Through a historical and descriptive analysis of changes in economic activity and population and the role of government, the book evaluates the forces that have shaped the Central Area.