The Library of Memory

Boey Kim Cheng’s memories of Singapore are closely tied to his recollections of reading and the old red-bricked National Library. Here, he remembers his love affair with the library, with words and with books.

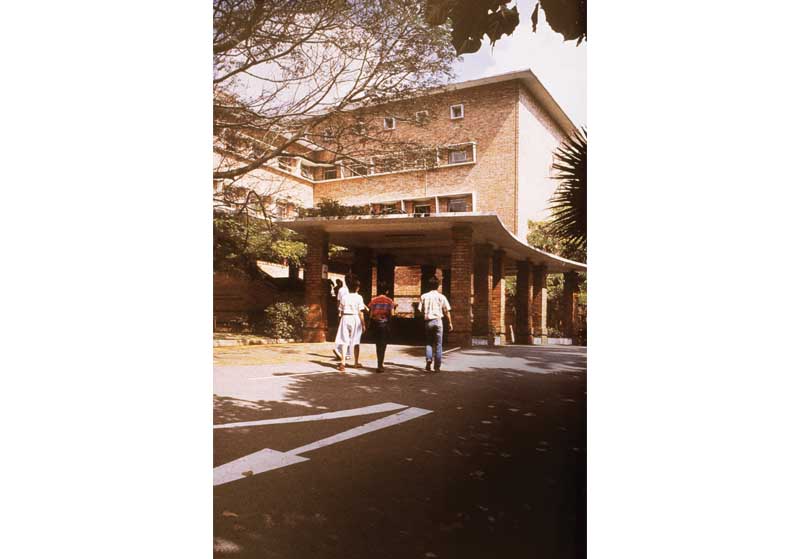

The old National Library on Stamford Road in 1990. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The old National Library on Stamford Road in 1990. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.From the street it looks nondescript, facing the Parisian-looking Park Mansion and around the corner from the Palladian Geological Institute, which looks a more fitting home to an establishment founded in 1788 to advance knowledge and research in all things Asian. It occupies No. 1 Park Street, now renamed Mother Teresa Sarani, a Modernist block with a clean rectilinear shape defined by protruding trim painted the ubiquitous vermilion red of Kolkata, its central block shielding the stairwell perforated by square holes. Kolkata’s four-storey building of the Asiatic Society, opened in 1965, the year Singapore and I were born, is pleasantly familiar; the old Rediffusion building in Singapore and numerous institutions built in that era, all vanished now, had the same provenance in British modernism.

I walk up the dusty steps and sniff the cool, dusky air, savouring the invigorating odour, a genteel, gentle whiff of slight must, stone, wood and paper. I have always loved the smells of old buildings and this is why I love this city, incredibly rich in buildings that have been allowed to age gracefully over time, their history palpable as much in their appearance as in the smells they wear. The security guard barely looks at me, his gaze focused on the busy street outside, where the pavement book-, bhelpuri- and shoe-repair- wallahs ply their trades. There is a defunct baggage scanner and a small cannon mounted on the stairwell.

Upstairs at the bag counter the male attendant lays his newspaper aside and instructs me to deposit my camera and to fill out a pink slip of paper that says “Admit Card for Casual Readers” and then to see Miss Mishra inside the library.

A musty silence hangs in the fluorescent-lit reading room, stirred by ceiling fans that give it a slightly drowsy feel. Running along the middle is a double row of wooden cabinets housing small drawers. “Here you find authors, subjects, all arranged,” Miss Mishra the librarian explains, who has interrupted her vadai tiffin to give me a tour. On the right are about 10 rows of tables; two pretty brunette German girls are poring over buckram-bound tomes, taking copious notes. Yesterday I overhead them in the Blue Sky Café talking excitedly about Csoma de Kórös, the intrepid Hungarian Orientalist who had travelled to the remotest parts of Ladakh and Zanskar to study Tibetan language and culture. He was an honorary member of the Royal Asiatic Society and from 1837 to 1841 worked as its librarian.

We cross a sky bridge to the original building of the society, a Tuscan-yellow two-storey flat-roofed building with French shutter windows, hidden from the street by the modern block. It has a gallery with oak balustrade and a rather grand central staircase. On the high shadowy walls time-dimmed paintings of Indian landscapes hang, their features obscured by the angle and grime; they remind me of European depictions of the Australian bush, panoramic views that could be anywhere in Europe except for a few natives planted in the background.

Spaced along the gallery are busts of the society’s luminaries: its founder William Jones, Csoma de Kórös, and Ashutosh Mukherjee, the formidable education pioneer who was thrice elected to be president of the Society. Miss Mishra steers me to the Sino-Tibetan and South-Asian Languages, the Sanskritic and other Indian Languages, and the Persian and Urdu rooms. Most of the books are covered in a thick film of dust. I take out an 18th-century book of Persian poetry and it nearly comes apart, some of the mouldering pages loosened from binding.

“So much here. Very precious,” I say politely, replacing the antique volume guiltily.

“Everything important comes to us. All kinds of books from the museum, the Geological Institute, the National Library. We are the Mother library,” Miss Mishra says proudly. I ask about the manuscripts room, but Miss Mishra says it is closed for “cleaning.” I wanted to see the famous Tipu Sultan collection.

We return to the reading room. There is no sign of a computer so far. I ask if the catalogue has been digitised but Miss Mishra’s head tilts in a yes-no sort of way. I leave her to her tiffin and make for the catalogue and its columns of drawers, each carrying a tag and a brass draw pull. I open them at random, too thrilled to remember what I am looking for, flipping the cards and relishing the sight of the typewritten entries, and the feel of my fingers walking the paper ridges. I am playing with the drawers, taking delight in the compact ease with which they slide open and close, marvelling at the rows of alphabetical listings that are the addresses of writers and books, in an age when the internet has banished them to the memory of older library users. The well-thumbed cards, redolent with human touch, many stained and creased at the top, their typescript sometimes broken, the ink uneven, some bearing corrections and white-out,1 possess for me talismanic power to evoke the essence of a book. It has been a long time since I have felt excited about being in a library.

These ranks of index cards have nudged open a door into my reading past. I can see my younger self touring the collection at the National Library in Singapore, relishing the idea of the entire library at my fingertips as I scan the accordion rows of cards. These 3-by-5 cards were first conceived by naturalist Carl Linnaeus to allow taxonomic classification and storage of scientific data, and adapted by Melville Dewey, the pioneer librarian whose classification system still steers reading journeys in the internet age. They were a library in their own right, each card a promise of what was to come, a map revealing routes to the different provinces and districts of the vast kingdom that is the library. Like the ocean it linked multitudes of destinations and made them contiguous.

My rite of initiation into library use began with an introduction to the catalogue, metal cabinets that were lined up back to back longitudinally in the middle, bisecting the floor space of the Adult Lending Section of the old National Library on Stamford Road. I had just signed up as a member at the loan counter, a square space with the return counter on the left side as you entered and the loan counter on the other, a team of librarians operating behind them. At the registration and information desk between the loan and return counters, I had been given four pocket-sized lending cards, beige, like the uniform of the library attendants, with a sleeve to hold the corresponding card books carried on the inside of their back cover as a sort of ID (on the flyleaf was glued the date due slip – there were books that boasted layers of library slips with innumerable loan dates, others bore only a few date stamps). The librarian told me to wait until there was enough of a group for the library tour.

It was 1978, my first visit to the National Library. I was in Secondary Two at Victoria School, and had outgrown the school library’s small stash of poetry books, with its mildewed Robert Browning and William Bryant, their stitches undone and gold-embossed spines peeling. I alighted outside the bookstores at Bras Basah, the academic ones doing a roaring trade in text and assessment books, their discount stock spilling over onto the five-footway in crates and boxes. It was here that I bought my first poetry book, The Albatross Book of Verse, with a wine-dark cloth cover. It was an anthology that I would dip into every night for a few years before sleep. Miraculously it has ended up in Australia with me, though I don’t remember packing it. Somehow a visit to the National Library was never complete without a tour of these bookstores. Your senses were honed, alert and excited, scouring the randomly arranged titles in the shady interior of second-hand stores with names such as Sultana and Modern.

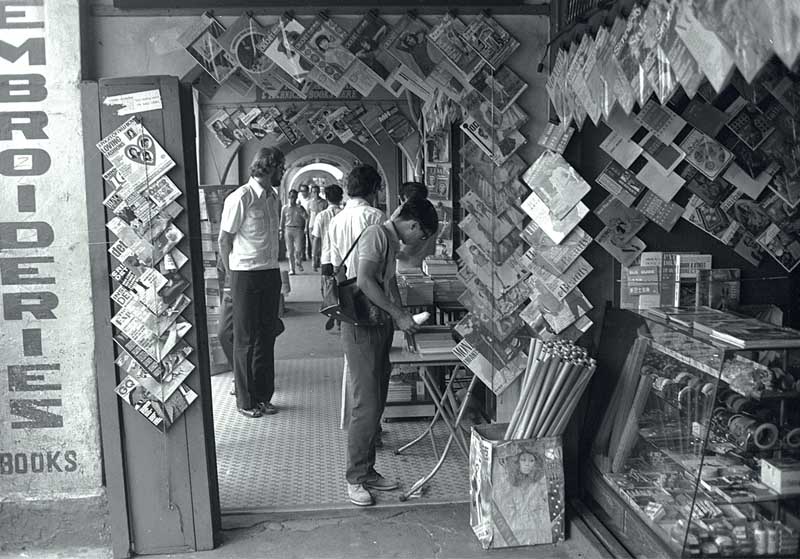

It was at one of these hole-in-the-wall bookshops along Bras Basah Road that the writer Boey Kim Cheng stumbled upon his first book of poetry, The Albatross Book of Verse. Old timers will recall bookshops with names such as Sultan and Modern (picture taken in 1972). The Straits Times © Singapore Press Holdings Limited. Reproduced with permission.

It was at one of these hole-in-the-wall bookshops along Bras Basah Road that the writer Boey Kim Cheng stumbled upon his first book of poetry, The Albatross Book of Verse. Old timers will recall bookshops with names such as Sultan and Modern (picture taken in 1972). The Straits Times © Singapore Press Holdings Limited. Reproduced with permission.You could then either take the route across the park to the old Tudor-style YMCA and walk past the National Museum to the library, or stroll down to St Joseph’s Institution and cross Bras Basah Road to the sarabat-stall-lined Waterloo Street, then ford the busy Stamford Road to a row of low, dingy shophouses and a tin-shed coffeeshop that served the best mee soto I have ever tasted, and finally up the steps to the stately but unpretentious and clean redbrick building that is the National Library, graced in front by a stand of royal palms, a canopy of yellow flame, saga and raintrees from Fort Canning just peering over its flat roof.

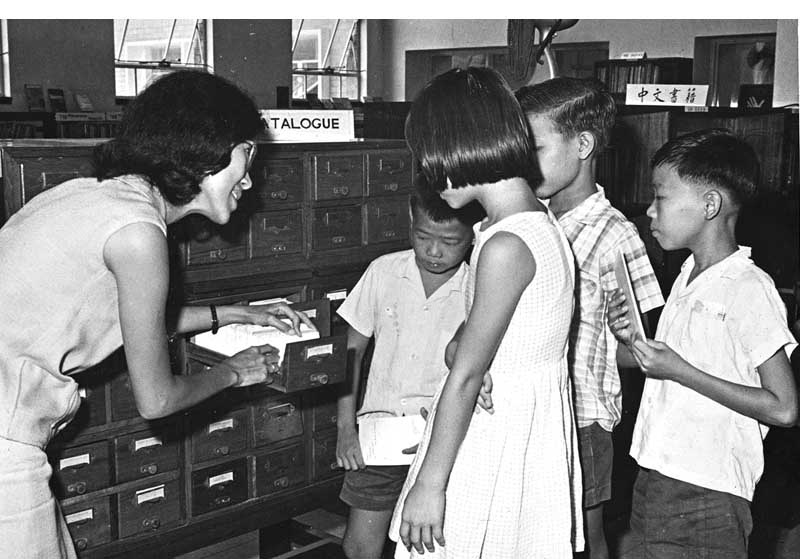

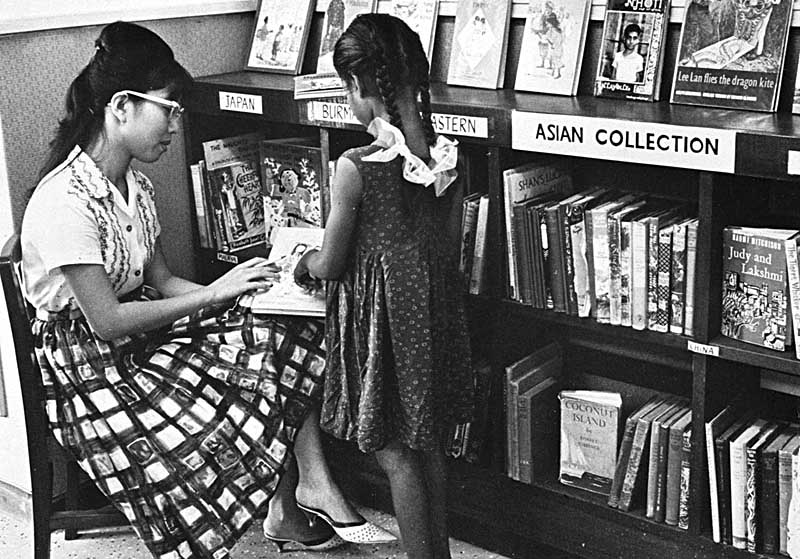

A librarian teaching young patrons how to use the catalogue in 1965. All rights reserved. National Library Board Singapore, 2014.

A librarian teaching young patrons how to use the catalogue in 1965. All rights reserved. National Library Board Singapore, 2014.The building, though unassuming in appearance and size, commanded attention and respect. Next to the grander domed National Museum, facing the Edwardian-style MPH building and the mock Venetian-Renaissance Stamford House up the road, it looked modern, and was criticised for being “out of character” and “forbidding.” But its exposed bricks gave it an earthy look, their various shades of red exuding warmth and depth; the medley of rectangle and square art deco white trim windows with jambs extending beyond the bricks and the rectilinear planes made it an honest, elegant and dignified edifice.

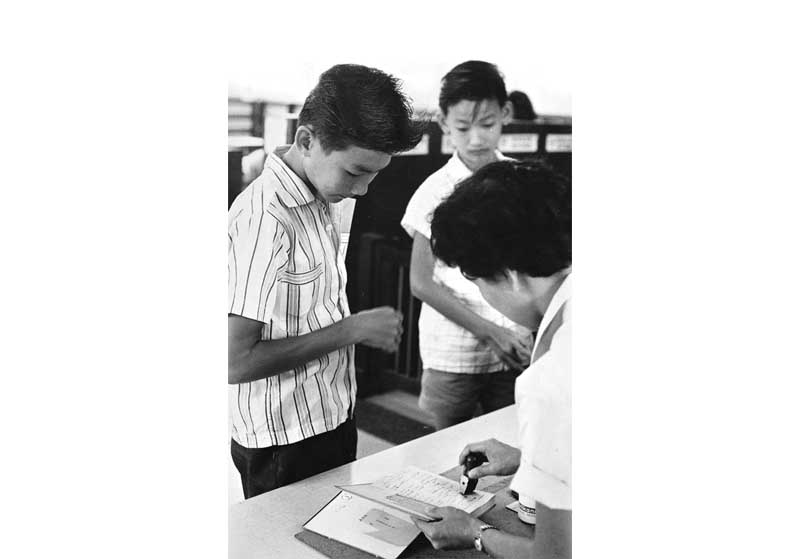

A librarian stamping the due date on a book at the old National Library in 1966. All rights reserved. National Library Board Singapore, 2014.

A librarian stamping the due date on a book at the old National Library in 1966. All rights reserved. National Library Board Singapore, 2014.I can see myself crossing the covered portico that was supported by brick pillars over the driveway, where cars would drop readers off, and walking up the tiled staircase flanked by brick banisters with slate tops, where teenagers would perch, chatting or waiting for friends. On the left of the lobby was a bag counter manned by a troupe of Malay attendants; there was a kind-faced old man wearing a songkok and his grumpy colleague who shuffled slowly because of a bad leg. In front was the courtyard, paved with cement slabs and fringed by potted plants. A few years before the library was demolished, it was given a facelift that included a fountain with a fleur de lis finial as part of the library’s overall renovation.

My first impression as I entered the Adult Section was the high windows and the way the sunbeams poured in through the glass and lay in oblong pools on the black and white tiled floor. You could see generous slices of the sky and the crowns of the trees on Fort Canning. Then you heard the cicada chorus filtering through and the whirring of swiveling wall fans; it all made a unique environment for the encounter with life-changing books.

The first stop on the library tour was the catalogue, the heart of the library that was a library in itself. I drew on it often, the thrill of the hunt, the whiff of the quest sharpened as I tried the author, then the subject approach, relishing the glide of the drawers, the neat click as you closed them. There was a set of wooden catalogue drawers that stood apart on a desk, housing entries of special collections, encyclopedias, journals and newspapers. But the primary thrill was letting yourself drift between the shelves, trusting your instinct to home in on the books waiting for your touch, your finger trailing their spines like playing keys, as you travelled the different “realms of gold,” to quote John Keats.

I have written elsewhere about how the library’s Oxford University Press edition of Keats, with its paper cover bearing a medallion-sized sketch of the poet by English portrait painter Joseph Severn cut out and pasted on the red cardboard cover, and the hardcover edition of Jon Stallworthy’s biography of Wilfred Owen, are key influences that have shaped the poet and person I am, but there were many more such encounters in the library, each like Franz Kafka’s axe-blow, each book telegraphing its revelatory portent through its aura. You feel all a-tremble, a current surging through your body, a wave bearing you away as you hold the book and surrender to its power.

A good book has potential for conversion and starting on it is like taking the road to Damascus. These are books that seem like messengers from another world washed on our shore, the message in the bottle seemingly intended for us. Henry David Thoreau says: “How many a man has dated a new era in his life from the reading of a book.” There were many moments of tremulous, convulsive, pleasurable discovery between the tall shelves of the library, and for me the memory of reading has become indivisibly entwined with memories of those navigating the aisles, attuned to the intimations of the books that seemed written and waiting for you. From book to book you travel, a memory map being plotted as you go. Reading is a physical journey through real space, the place of reading an intrinsic part of the reading experience and memory, a dimension sadly missing in virtual libraries.

In Stephen Poliakoff’s Shooting the Past, a thought-provoking television drama about a photographic library and the lives of its librarians as it is threatened with closure, the eccentric Oswald Bates knows exactly where each image is stored, amid the chaotic arrangements of the boxes that make up the collection. He has a physical and emotional relationship with the collection, and makes a desperate bid to keep it from being displaced and dispersed. For him each photograph houses a memory, an archived story to be read and brought to life, and the entire collection is a library of memories.

Perhaps Oswald’s extraordinary mental catalogue can be explained by the mnemonic technique inspired by the Greek poet Simonides of Ceos. According to Roman philosopher Cicero, Simonides was at a banquet in Thessaly to present a poem to his host when the roof of the banquet hall collapsed. He had stepped outside when it happened and returned to identify the mangled bodies under the rubble by consulting his visual memory of the seating arrangement around the table. This spatialisation of memory was pivotal to the mnemonics of orators like Cicero, who was able to commit vast tracts of speech to memory by visualising them as inhabiting specific points of a place. St Augustine would later compare memory to a vast storehouse containing all our memories, lived sensations and thoughts, dreams and hopes.

The library is such a storehouse, not only because each book it contains is a work of memory, but more vitally because it contains the memory loci for readers whose lives have been changed by it. The reading experience is not just about establishing a relationship to a book or author, but also a long-term relationship with a library, knowing its character, the promise and sometimes the dangers it holds.

I loved navigating the fiction section on the left side of the room and lingering in the philosophy shelves after it, before moving on to the literature rows to the right. Each section breathed a distinct odour of promise; the fiction shelves were exciting in their range. I took out all of Dostoevsky’s and Kazantzakis’, and inhabited the dark nights of St Petersburg and the sun-drenched earth of Crete fully. The air around the philosophy shelves was more sombre, and the books wore a graver odour, a heavy woody whiff with an underlay of acidic tang. Here I entered a sort of dark night of the soul when I picked out Schopenhauer, Nietzsche and Kierkegaard. A dark oppressive weight descended but at the same time I felt a thrilling sense of discovery, as though the real truth, the Grail awaited me in these books if I had the courage to read them.

Further to the right, perpendicular to the axis of the philosophy section, lay the literature shelves. The English shelves offered visions of the English countryside. I desperately wanted to possess Keats’ poems and strangely Housman’s A Shropshire Lad, which I eventually copied out with a fountain pen into a notebook (it was the pre-photocopy age). Behind the AngloAmerican literature shelves, across from the wall section of art-books, was a small collection of world literature in translation. I remember leaning against the metal bookcase, poring over Vincente Aleixandre and Odysseus Elytis’ poems, the afternoon light from the windows acquiring an exquisite, sensual Mediterranean quality as I stood immersed in the poems from a foreign world. Here too, I sniffed out Pablo Neruda’s Residence on Earth and was mesmerised by the deep chords that rise from the farthest, deepest places of the human soul and experience. The book had an earthy feel to it, with its comfortable weight, its cut pages and a dust cover with a monotone image of what must be the rugged mountains of the Chilean coast.

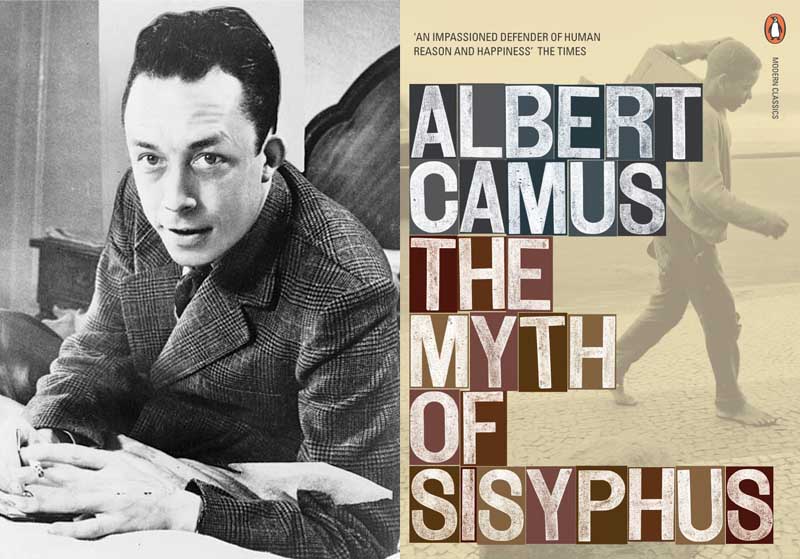

Then I found Albert Camus’ The Myth of Sisyphus; it had a salmon-pink dust cover with stark letters and no image, one of the books that strike like disaster, to use Kafka’s words, at the heart of the reader, for it intensified the existentialist phase of my reading. It was a difficult, searching time; the library became a refuge when the sense of alienation in a school that placed emphasis on the sciences and trouble at home made me an outsider who sought to stay away from home and school as much as possible. Reading Camus strangely lent me a sense of strength; Sisyphus rolling his rock up the hill again and again as a form of rebellion was grim inspiration: “The struggle itself towards the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.”

I went to the catalogue and tracked down more Camus. The Outsider was in the fiction section, The Rebel in philosophy, Lyrical and Critical Essays in the French literature section. This reflects the challenge of classification but also underscores the physical act of reading, the routes you take to get from book to book. Like The Myth of Sisyphus, Essays was plain and austere in appearance, with just the letters in stark relief. I have since bought a pre-read paperback copy of it in Thessaloniki in a bookstore of mostly Greek books, a cover with a portrait of Camus in discussion, leaning forward with his penetrating gaze and hands spread to underscore a point. From these essays, especially the ones set in Algiers, I derived a sense of stoic calm, even joy, as I struggled in my youthful dark night. The tenet “There is no love of life without despair of it” has been a shaping belief.

The writings of French Nobel laureate author Albert Camus (1913–1960), especially The Myth of Sisyphus, made a deep impression on Boey Kim Cheng during his formative years. It spurred him to read several of Camus’ other books. Left: Portrait from New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection, 1957. Right: Cover image all rights reserved, Penguin, London, 2000.

The writings of French Nobel laureate author Albert Camus (1913–1960), especially The Myth of Sisyphus, made a deep impression on Boey Kim Cheng during his formative years. It spurred him to read several of Camus’ other books. Left: Portrait from New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection, 1957. Right: Cover image all rights reserved, Penguin, London, 2000.In Time Regained, Marcel Proust remarks of the relationship between reading and memory:

If, ever in thought, I take up François le Champi in the library, immediately a child rises within me and replaces me, who alone has the right to read that title François le Champi and who reads it as he read it then with the same impression of the weather out in the garden, with the same old dreams about countries and life, the same anguish of the morrow.

I remember reading Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy and pondering his insights into Wagner and then going upstairs to the audio-visual section of the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library to listen to Parsifal and the Ring Cycle. I started alternating between the fan-cooled Adult Section and the air-conditioned Reference Library. I sifted the catalogue of the audio-visual section and filled up request slips for vinyl treasures. The librarian would direct me to a listening booth and go into a backroom where the records were stored. I had discovered Mahler at the British Council Library opposite Clifford Pier, and here at the National Library I listened to his Third Symphony after reading Thus Spake Zarathustra. It was a heady mix, and for days something akin to delirium possessed me, the secret truth of Nietzsche’s “Midnight Song” scored deeply in Mahler’s notes. But there was also the anxiety that had been accumulating since I had started reading Keats, the fear that I was taking a path less-travelled and the way ahead was fraught with uncertainty and pain.

One day I set out from the National Library to the British Council Library with a copy of Rimbaud’s Illuminations in my schoolbag. The two libraries had become key reference points between which my reading and life took their bearings; the routes and distances between them now provide the measures of memory. It was a daily ritual, starting out from the National Library after spending the afternoon there, walking past Capitol Cinema, across High Street to the Singapore River, where flotillas of tongkangs were berthed. My head was full of Rimbaud, my senses reeling from his intoxicating lines. The chugging of tongkangs carrying goods to the godowns upstream and empty ones going out to the harbour, their wide wakes slapping gently the slimy steps and pilings, the composite smell of bilges, mud and salt water, the reek of oil and timber hanging in the air, and the afternoon light percussive on the khaki-coloured tides gave me Rimbaud’s “disorientation of the senses.” I felt I was on the cusp of something, a sense of trespass and uplift; I wasn’t afraid anymore of the life of poetry, of the danger and solitude it meant. That night, after reading at the window seat in the British Council Library, looking up occasionally from Four Quartets at the transactions outside Change Alley, and across at Clifford Pier and the boats at anchor in the roads, I walked to the Cavanagh Bridge, which was deserted and dim-lit after office hours, and celebrated that day of epiphany by lighting up my first cigarette.

Patrons browsing through the Asian Children’s collection at the National Library on Stamford Road. All rights reserved. National Library Board Singapore, 2014.

Patrons browsing through the Asian Children’s collection at the National Library on Stamford Road. All rights reserved. National Library Board Singapore, 2014.Here in the Asiatic Society reading room, Miss Mishra hands me the 12th volume of Asiatick Researches or Transactions of the Society Instituted in Bengal for Inquiring into the History and Antiquities, the Arts, Sciences and Literature, of Asia. I hold its worn leather cover, thrilled to find on its title page that it was published in 1818, on the eve of Raffles’ arrival in Singapore. I have thumbed through the catalogue and found Raffles’ article “On the Maláyu Nation, with a Translation of its Maritime Institutions.” Touching the antique leaves, which are riddled with perforations in some places, the route of memory seems to have touched home. Raffles can be credited with the founding of the National Library, though its predecessor the Raffles Library, created in 1823, was open only to the British.

Feeling and smelling the aged paper, the old National Library is no longer a ghostly memory, a black hole that has swallowed up the reading history of a nation, the reading memories of generations of readers. Over the tunnel that seems such poor justification for the library’s removal, the reassuring red-brick building stands on the rise towards Fort Canning, beckoning to the skinny boy in slippers walking up its wide steps, its shelves calling with books that seem to read and write his life as he reads, and somewhere along the journey memory and reading will become one, as he wanders the tall aisles of books, waiting to be found in the library of memory.

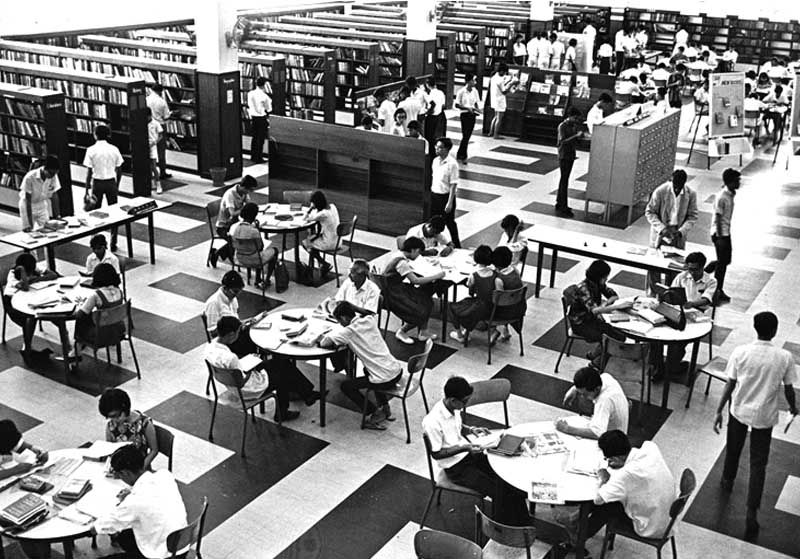

The lending section of the old National Library in 1962. All rights reserved. National Library Board Singapore, 2014.

The lending section of the old National Library in 1962. All rights reserved. National Library Board Singapore, 2014. Singapore-born Boey Kim Cheng has written five collections of poetry and a travel memoir Between Stations. Boey lives in Australia, where he is now a citizen and teaches creative writing at the University of Newcastle. He is currently a writer-in-residence at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore.

Singapore-born Boey Kim Cheng has written five collections of poetry and a travel memoir Between Stations. Boey lives in Australia, where he is now a citizen and teaches creative writing at the University of Newcastle. He is currently a writer-in-residence at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore.NOTES

-

White-out is a brand of correction fluid. ↩