First Words: Women Poets from Singapore

Poems written by Singapore’s women writers in the 1950s to 1970s depict both their personal and national struggles. Gracie Lee highlights these poets and the literary works that captured the sentiment of the times.

Hedwig Aroozoo was not only one of Singapore’s earliest female poets, but also the director of the National Library of Singapore from 1960 to 1988. Photography by Sean Lee.

Hedwig Aroozoo was not only one of Singapore’s earliest female poets, but also the director of the National Library of Singapore from 1960 to 1988. Photography by Sean Lee.From Hedwig Aroozoo’s parodies of 1950s Singapore politics to Angeline Yap’s poetic responses to nationhood, the verses of Singapore’s early women poets have engaged our imagination, emotions and intellect, enlarged our understanding of the human condition, and enriched the literary and cultural heritage of Singapore. It is hoped that this overview of poetry written by Singapore women in the 1950s–70s will stir the interest of readers to explore the wealth of local literature available in the National Library’s Singapore collection.

Hedwig Aroozoo (1928–)

During the 1950s, the University of Malaya – now the National University of Singapore (NUS) – was fertile ground for creative expression when Singapore attained self-government and later nationhood. Gripped by rising nationalistic fervour, a group of English-educated students sought to create literary works and to find an appropriate idiom that would express the culture, landscape and identity of the Singapore-Malaya Union. Academics have identified this developmental phase as the beginning of Singapore literature in English.

One of the earliest women poets of this period was Hedwig Anuar nee Aroozoo. As a literature student at the University of Malaya, she contributed one of her early poems “A Rhyme in Time” (later republished as “Fragments of a Wasteland” in 1999) to the Malayan Undergrad, a student journal, in 1951. The poem, which examines colonial Singapore languishing in the embers of the British Empire, was conceptualised as a satirical piece for a class exercise on T. S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land” and later anthologised in Litmus One, the first anthology of Malayan verses in 1958. The poem was singled out by leading Malaysian poet Ee Tiang Hong as a work that “merits a place in any anthology of Malaysian poetry that has a historical import”.1

After graduation, Aroozoo furthered her studies in London where she co-edited Suara Merdeka the organ of the Malayan Forum. This was a political discussion group formed by Malayan students in London and its alumni include political luminaries such as Goh Keng Swee, Lee Kuan Yew and Toh Chin Chye. Several of Aroozoo’s political parodies appeared in this newsletter. “Love Match” (1956), a satirical piece on the merger of Singapore and the Federation of Malaya, was one of them. This piece drew its inspiration from then Chief Minister Lim Yew Hock’s comment to the press on his return from discussions with Tengku Abdul Rahman on a possible union between Singapore and Malaya. He said, “Well, gentlemen, the love-making has started. As you know yourselves, once you start making love, there are always chances of a marriage.” Aroozoo seized on this analogy of courtship and matrimony to depict the political bartering and complexities of merger. In this poem, Singapore is personified as the lady, and Malaya the gentleman.

The lady says she’s willing

She declares the prospect thrilling,

But the gentleman isn’t quite so sure.

He’s not quite so romantic,

He’s driving her quite frantic –

Can it be that she lacks enough allure?

(Lines 1–6; Under the Apple Tree, p. 16.)

Though Aroozoo was a contemporary of well-known historian Wang Gungwu, who belonged to a group of pioneering writers, she is not perceived as part of that circle for her writing was primarily a private endeavour. Her poems have mainly appeared in non-literary journals, many were never published, and some (such as her love poems) were even destroyed. After graduation, Aroozoo went on to carve out an illustrious career as the Director of the National Library and discontinued her poetry writing. It was only in 1999 that her published poems were gathered and re-introduced in Under the Apple Tree: Political Parodies of the 1950s.

In 1999, Hedwig Aroozoo’s published poems were collected and released in Under the Apple Tree. All rights reserved, National Library Board Singapore, 2014.

In 1999, Hedwig Aroozoo’s published poems were collected and released in Under the Apple Tree. All rights reserved, National Library Board Singapore, 2014.Wong May (1944–)

As higher education in English was rare in the early years, creative writing in English was scarce right up to the mid-1960s. This is even more apparent in Singapore women’s writing as women had far less educational opportunities than men. In Edwin Thumboo’s seminal anthology on Singapore and Malaysia poetry, The Second Tongue (1976), he writes: “Women are now beginning to enjoy professional and intellectual parity with men…Before the mid-sixties, very few women wrote creatively; there were no women among the pioneer poets. Wong May and Lee Geok Lan [Malaysian] were about the first.”2 He also adds that “women have contributed positively to that shift in the choice and treatment of theme from the public to the personal” and have also introduced “delicate” nuances to the poetic language. The nascent growth of women writers from the mid-1960s onwards was noticed by NUS academics Rajeer Patke and Philip Holden as well. In their survey of pre-1965 Malaysian and Singapore writing, Wong May, Daisy Chan Heng Chee, Theresa Ng and Lee Tzu Pheng were cited as leading women poets of this period.

Wong May occupies an interesting place in Singapore literature. Born in Chongqing, China in 1944, she was raised in Singapore and received her Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of Singapore (now NUS). She left Singapore to study in the United States in 1966 and eventually settled in Dublin, Ireland. A contemporary of Arthur Yap and Robert Yeo, her early poems appeared in Focus: The Journal of the University of Malaya’s Literary Society and in several key anthologies on Singapore and Malaysian writings such as The Flowering Tree (1970), Seven Poets (1973) and The Second Tongue. Though Wong went on to publish three collections of poems overseas, A Bad Girl’s Book of Animals (1969), Reports (1972) and Superstitions (1978), only her early poems in Singapore are entered into discussion as national literature. Nevertheless, her place in Singapore’s canon of writers is undisputed.

In the introduction to his anthology A Private Landscape (1967) David Ormerod lauds Wong May as a “powerful and valid voice” who has the potential to lead the development of English-language poetry in Malaysia and Singapore.3 The blurb on her first book of poetry provides further evidence of this close association with Singapore; her place of birth was erroneously printed as Singapore. Wong’s fourth volume of poems Picasso’s Tears is due to be released in 2014.

Aside from her nationality, Wong’s place in Singapore literature is made more complex by the type of poetry she writes. Most of her poems are concerned with the personal and are universal in their treatment of the subject matter. Only a handful of poems such as “This Fine Day” and “Study of a Millionairess: Still Life” contain recognisable Chinese or local references.

Despite her obscurity from the general reading public, Wong’s poems have been well-received by critics locally and abroad, receiving descriptions such as quirky, unpredictable, intense, graceful and otherworldly. Stylistically, her poems are marked by silences – a quality Wong terms as “wordlessness”, 4 which she relies on to convey the limitations of language in communication and in establishing human connection. She also adopts an intriguing elliptical structure in a number of her poems. These traits are visible in poems such as “The Shroud”, a poem on the loss of childhood innocence:

The old school uniform

With the little childish delights and giggles

Is folded and locked up in the top drawer

Forever.

Shall I cry?

I am no longer a child

My eyes so dry

It’s not easy to cry.

Yet I hear somebody weeping –

Crying louder and louder – howling

I feel her tears –

She is the girl locked up in the top drawer.

(Lines 9–20; Seven Poets, p. 111)

Lee Tzu Pheng (1946–)

Like Wong May, Lee Tzu Pheng is a writer who eschews the public role of the poet for the private. She has published five volumes of poetry to date: Prospect of a Drowning (1980); Against the Next Wave (1988); The Brink of an Amen (1991); Lambada by Galilee and Other Surprises (1997); and Catching Connections: Poems, Prosexcusions, Crucifications (2012).

Lee enjoyed early success, winning prizes for her poems “Present from the Past” (1966) and “My Country and My People” (1967) as an undergraduate at the University of Singapore where she read literature under Professor D. J. Enright. (An accomplished poet in his own right, Enright’s literary contributions have been largely overshadowed by his high profile altercation with the government for his critique of Singapore’s cultural policy in the “Enright Affair”.)

Lee’s poems first appeared in literary journals such as Focus and Poetry Singapore and anthologies such as The Flowering Tree. They were collected and released as a collection in her debut volume Prospect of a Drowning in 1980. The collection brings together 38 poems written between 1966 and 1973 when she was an undergraduate and graduate student. She took a long hiatus from creative writing in 1973 and returned to the craft only in 1987.

Regarded as one of the founding triumvirate of poetry in Singapore (Edwin Thumboo and Arthur Yap being the other two) and a national poet, Lee does not, however, “consciously set out to write something representative of the nation”.5 Instead she crafts poems from contemplations on her inner world and her observations of everyday life. Her poems reveal a keen sensitivity to language and an emotional honesty with the subject matter. Thumboo notes that her poems are “neither over nor under-written”6 and Patke and Holden commend her “voice of steady thoughtfulness”, and her ability to “dwell on feelings without risking exhibitionism or sentimentality”.7 Although Lee’s inclinations are toward her internal world, Patke argues that she is not merely a poet of the private voice for her oeuvre explores the realms of the personal, sociopolitical and spiritual.

No discussion on Lee is complete without reference to “My Country and My People”. Intended to be a personal piece that Lee wrote for herself, the poem has since been lauded as a national poem though it had been, ironically, banned from the airwaves in the 1970s, supposedly for its reference to “brown-skinned neighbours”. The famous opening lines to her poem continue to resonate with generations of Singaporeans, unerringly capturing the ambivalence and contradictions of being Singaporean: “My country and my people/ are neither here nor there, nor/ in the comfort of my preferences/ if I could even choose”. The poem goes on to explore the poet’s disquiet with the disappearance of nostalgic familiar places that have made way for the sterile ubiquitous city and material progress. At the close of the poem, the poet turns the discourse around by reversing the order of the opening lines with: “I claim citizenship in your recognition/ of our kind./ My people, and my country,/ are you, and you my home.” Here, she asserts her personal vision that it is the kinship among neighbours that makes Singapore both a country and a home. The success of “My Country and My People” has been attributed to Lee’s ability to conflate her internal and external realities, bringing together personal and public histories, giving meaning to the larger political context through the experience of the individual.

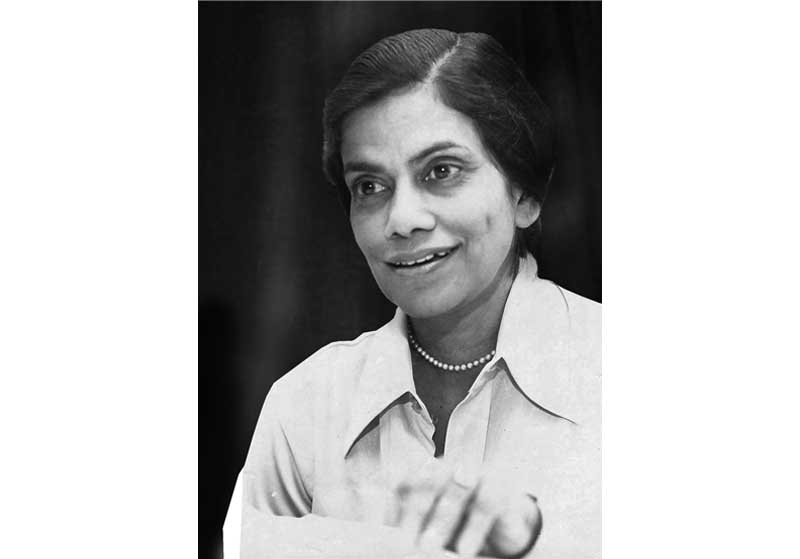

Cultural medallion recipient (1985), Lee Tzu Pheng, is one of Singapore’s most distinguished poets. All rights reserved. Eric Foo Chee Meng 1979–2001. Courtesy of National Arts Council Singapore.

Cultural medallion recipient (1985), Lee Tzu Pheng, is one of Singapore’s most distinguished poets. All rights reserved. Eric Foo Chee Meng 1979–2001. Courtesy of National Arts Council Singapore.Chung Yee Chong (1950–)

Chung Yee Chong was another promising poet in the 1960s and 70s. She exited the local literary scene after she left Singapore. Born in Hong Kong, Chung lived in Indonesia before moving to Singapore where her father had taken up a teaching post in Nanyang University (now Nanyang Technological University). She developed her love for poetry writing during her preuniversity days at Serangoon Secondary School under the guidance of Arthur Yap who was her English teacher. In an interview, Chung recalled that she was seized by the writing bug, finishing one poem a day and publishing her first poem in a school magazine. She continued writing when she entered university and her works have appeared in Focus and anthologies such as The Flowering Tree and The Second Tongue.

The majority of her works (23 poems altogether) was published in Five Takes (1974), which features the poems of five poets. She was the only woman among the five which included Sng Boh Khim, Arthur Yap, Yeo Bock Cheng and Robert Yeo. After graduating with Honours in English in 1973, Chung worked as a copywriter at various advertising agencies before settling in the United Kingdom where she gained success as a painter. Chung continues to live and work in the United Kingdom as an artist. Though she has not released any poem since, she did publish a novel set in communist China titled The Bitter Sea in 2012.

Chung’s poems delve into a range of subjects, though man-woman relationships and the passage of time are recurrent themes. The poem titled “10 a.m. – a wife’s report” offers us a glimpse of the latent talent present in her creative writings.

early

in the morning

I noticed: you left

and took with you

the scent of after-shave lotion

tobacco, and whatever else i cannot define

except this sense that

somehow you have wrung out my life

with the towel you hung to let dry.

(Lines 1–11; Five Takes, p. 28)

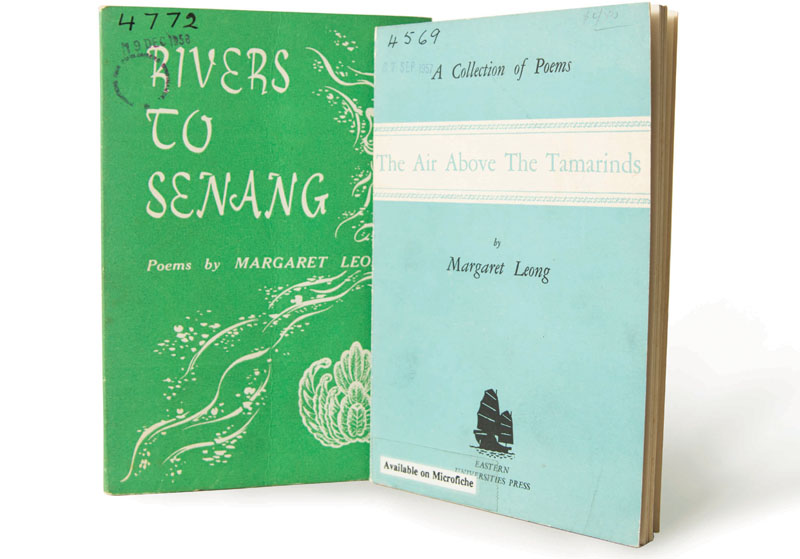

Margaret Leong (1921–2012)

Margaret Leong’s transient affiliation with Singapore puts her in the same league with Wong May and Chung Yee Chong. A white American expatriate who married a Malayan Chinese, Leong came to Singapore in 1949 with her journalist husband. She taught at St Anthony’s Convent and was an advocate in the local literary scene. She was also a prolific writer. During her 14-year stay here, she published at least seven known literary works: The Air Above the Tamarinds (1957); Rivers to Senang (1958); My First Book of Poems (1958); Songs of Malaya (1959); The Shamen’s Ring (1961); and Coral Sands Volumes 1 and 2 (publication year unknown). My Second Book of Poems (1977) was published after she left Singapore for her home state of Missouri in 1963. She continued to be active in the literary scene after her return to America and founded the New York Literary Society Press. She passed away in Columbia, Missouri, in 2012.

Dubbed a “Malayan poet”8 and a “Singapore poetess”9 by the press, Leong’s lyrical poems are endowed with a rich local flavour that is shaped and informed by the poet’s fascination with the sights and sounds of the region’s flora, fauna, customs and ways of living. Her poems are infused with romanticised images of the Malayan landscapes and its inhabitants. Some of the place poems on Singapore include “The Japanese Cemetery”, “Tomb of Iskandar Shah”, “Raffles Quadrangle”, “Rainbow at Changi”, “Jurong” and “By Tanah Merah”. Much of her work was written for children and youths, with the exceptions of The Air Above the Tamarinds and Rivers of Senang. For instance, My First Book of Poems was written for 10-year-olds and used as a primary school textbook. Writer and academic Shirley Geok-lin Lim believes that for this reason, her works have received little critical attention from scholars. This omission has, however, been addressed with the anthologising of her poems in Writing Singapore: An Historical Anthology of Singapore Literature (2009), and the republication of her juvenile poems in The Ice Ball Man and Other Poems (2011). The following extract from “Pasir Ris-Sunset” illustrates the keen Malayan sensibility that she evoked in her poetry:

Where the kelong cuts across the sea

Like a wooden-handled kris

There is a mellifluous song

In the seas off Pasir Ris

(Lines 9–12; The Air Above the Tamarinds, p. 17)

Margaret Leong’s works were infused with the sights and sounds of Malaya. She was an accomplished writer and educator. All rights reserved, National Library Board Singapore, 2014.

Margaret Leong’s works were infused with the sights and sounds of Malaya. She was an accomplished writer and educator. All rights reserved, National Library Board Singapore, 2014.Geraldine Heng (1954–)

Geraldine Heng’s Whitedreams (1976) lays claim as the first book of poetry in English written by a Singapore woman that is published in Singapore. The collection contains 30 poems on various subjects, with a number that focus on the experiences of a woman: her moods, feelings and relationships. Reflecting her feminist leanings, Heng also led the compilation of the first anthology of writing by Singapore women, The Sun in Her Eyes: Stories (1976).

At an early age, Heng was winning essay competitions and taking on assignments as a freelance writer in local student magazines. After graduation, she lectured at NUS and was also an active participant in the local literary scene as a poet, reviewer and moderator at seminars. She eventually left Singapore and began an academic career in medieval literature in the United States. Today, she is an associate professor at the University of Texas, Austin, where she continues to teach and research on medieval literature.

Heng’s poems have appeared in various periodicals such as Commentary, New Directions and Singa and have been anthologised in The Second Tongue, Singapore Writing and Articulations. Praised for her “fine feeling” and use of “appropriate idioms”,10 Heng’s facility with words can be seen in poems such as “Little Things” that expresses child-like delight with the Chinese mooncake and lantern festival:

we were a crooked line of giggling children untidy-happy

delight burning on our faces

brighter than the muted flickers of light

straining to be released

from paint-gay lanterns

earnest hands tightly clutched

bamboo rods from which hung

our lives and souls and

concentration

(Lines 1–10; Whitedreams, p. 30)

Geraldine Heng is an associate professor at the University of Texas, Austin. Her work has earned her six research fellowships to date. Courtesy of Geraldine Heng.

Geraldine Heng is an associate professor at the University of Texas, Austin. Her work has earned her six research fellowships to date. Courtesy of Geraldine Heng.Nalla Tan (1923–2012) and Rosaly Puthucheary (1936–)

Nalla Tan and Rosaly Puthucheary were two prolific women writers in the 1970s. Though their works have not achieved critical standing, they are mentioned in this article for their contributions to the production of women writing.

Born in Ipoh, Malaysia, Nalla Tan is better known for her ground-breaking work as a physician on sex education in schools and her advocacy work with women in Singapore. She has written two poetry collections, Emerald Autumn and Other Poems (1976) and The Gift, and Other Poems (1978). They were republished, along with new poems, in The Collected Poems of Nalla Tan in 1998. She also wrote prose, which met with greater success. Her short stories have been anthologised in The Sun in Her Eyes and Singapore Short Stories Volume II, and released as a collection as Hearts and Crosses (1989). Much of Tan’s poems draw on her life experiences growing up in Ipoh, and living in Singapore and the causes she championed. The following extract, from “Coffee at Eleven”, satires the world of kept mistresses.

Coffee at eleven

Singapore mean time.

Leisured women,

Chauffeur driven

With nothing better to do

Than to sip hot coffee

Replacing the ‘mems’

Of not so long ago

Who’s being kept?

What, a second establishment!

With Woman’s Charter!!

(Lines 1–8, 30–32; The Gift and Other Poems, pp. 34–35)

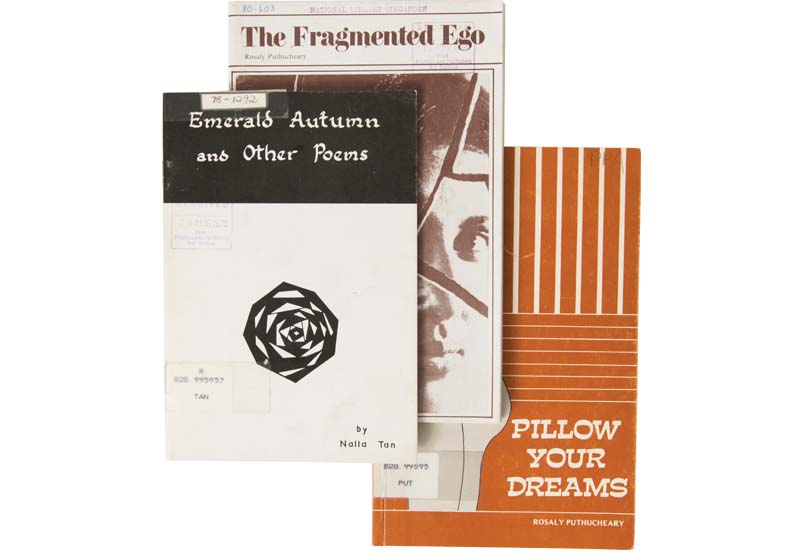

Rosaly Puthucheary, sister of former left-wing politician James Puthchucheary and Malaysian poet Susie Puthucheary, was born in Johor Bahru. She came to Singapore in 1974 and is now a retired teacher. To date, she has published six volumes of poetry Pillow Your Dreams (1978); The Fragmented Ego (1978); Dance on His Doorstep (1992); Mirrored Images (2008); Footfalls in the Rain (2008); My Burning Hill (2012); and two novels The Tessellated Path (2009) and In the Wake of Terror (2012). Her poems from the 1970s are short introspective pieces that dwell on the subject of romantic love and self-discovery. Poems, such as “A Door-Mat”, hint at her feminist sentiments.

I will not be your door-mat

a piece of convenience

waiting at the door,

to dust the ash of your desire

a rug to throw your weariness

crushing the rush of my fibre

with your heavy indifference.

(Lines 1–7; Pillow Your Dreams, p. 1)

Nalla Tan wore many hats – doctor, academic, writer. She advocated a diverse range of issues from health education to women’s rights. Courtesy of Tan Ying Hsien.

Nalla Tan wore many hats – doctor, academic, writer. She advocated a diverse range of issues from health education to women’s rights. Courtesy of Tan Ying Hsien. Rosaly Puthucheary has been writing poetry since 1952. She obtained her doctorate in English Literature at the National University of Singapore. Courtesy of Rosaly Puthucheary.

Rosaly Puthucheary has been writing poetry since 1952. She obtained her doctorate in English Literature at the National University of Singapore. Courtesy of Rosaly Puthucheary. These books are a sampling of Rosaly Puthucheary’s poetry. She has also written two novels to date. All rights reserved, National Library Board Singapore, 2014.

These books are a sampling of Rosaly Puthucheary’s poetry. She has also written two novels to date. All rights reserved, National Library Board Singapore, 2014.Angeline Yap (1959–)

Angeline Yap is the youngest poet featured in this article. She began writing as a child and contributed many poems during the 1970s and 1980s to periodicals such as Saya, Focus and Singa. Nurtured by the late Marie Bong who taught her to write not with her head but her heart, Yap won many prizes in writing competitions organised by the Ministry of Culture, NUS Literary Society and the National Book Development Council. Marie Bong was the former headmistress of CHIJ Katong and long-time editor of the student literary magazine Saya. Yap’s poems were republished in 1986 under the title Collected Poems, and have appeared in contemporary anthologies such as The Poetry of Singapore (1985) and Journeys: Words, Home and Nation (1995). Yap is also a mentor with the National Arts Council’s Mentor Access Project and released her second book of poems Closing My Eyes to Listen in 2011. Her latest outing sees a shift in direction towards spiritual contemplation, much like Lee Tzu Pheng’s more recent works. The following poem written in “almost colloquial”11 language is the first of two poems titled “Song of a Singaporean”.

Yap’s poem, “Colours”, was also featured in the exhibition “Calligraphy in Collaboration with Poets and Artists” with American calligrapher, Thomas Ingmire, in 2013.

In Modern English (Song of a Singaporean) (1975)

(i)

Are you mad with me

‘Cos I’m not hooked

On Culture

Spelt with capital ‘C’,

‘Cos I don’t dig ballet,

Don’t talk Chopin,

Beethoven or Bizet,

‘Cos my spirit answers

To the call of the Chinese flute

And it dances

To the rhythm of the Malay beat,

‘Cos my culture starts with ‘c’,

Not capital,

Not spoken with uplift of nose or brows,

Can you be mad with me?

(Lines 1–15; Collected Poems, p.10 )

Collected Poems by Angeline Yap was published in 1986. All rights reserved, National Library Board Singapore, 2014.

Collected Poems by Angeline Yap was published in 1986. All rights reserved, National Library Board Singapore, 2014. Gracie Lee is a Senior Librarian with the National Library. She was involved in the curation of the Singapore Literary Pioneers Gallery and in the compilation of Singapore Literature in English: An Annotated Bibliography (2008).

Gracie Lee is a Senior Librarian with the National Library. She was involved in the curation of the Singapore Literary Pioneers Gallery and in the compilation of Singapore Literature in English: An Annotated Bibliography (2008).REFERENCES

Angeline Yap: Biography and brief introduction. (n.d.). Retrieved from Contemporary Postcolonial & Postcolonial Literature in English website.

Hedwig, A. (1999). Under the apple tree: Political parodies of the 1950s. Singapore: Landmark Books. (Call no.: RSING S821 ANU)

Bandara, L. (1980, January 13). Rosaly does what comes naturally and loves…. The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Bong, M. (Ed.). (1979). Saya. Singapore Educational Publications Bureau. (Call no.: RSING 828.995957 SAY)

Brewster, A. (1989). Towards a semiotic of post-colonial discourse: University writing in Singapore and Malaysia. Singapore: Heinemann Asia for Centre for Advances Studies. (Call no.: RSING 808.1 BRE)

Call to form a Malayan club to foster interest in poetry. (1960, August 13). Singapore Free Press, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Chan, F. (1999). Silences may speak: The poetry of Lee Tzu Pheng (pp. 11, 14, 38, 44–45, 52–55). Singapore: Times Books International. (Call no.: RSING 828.995957 CHA)

Chung, Y.C. et al. (1974). Five takes: Poems. Singapore: University of Singapore Society. (Call no.: RSING 828.995957 FIV)

College of Liberal Arts. (n.d.). Geraldine Heng. Retrieved from The University of Texas at Austin website.

Dedicated poetry to son who hates it. (1956, December 8). The Straits Times, p. 20. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Durai, J. (2012, March 28). Pioneer sex educator Nalla Tan dies. The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Koh, T.A. (2002). The sun in her eyes: Writing in English by Singapore women (pp. 232–240). In Mohammad A. Quayum & P. Wicks (Eds.), Singaporean literature in English: A critical reader. Malaysia: Universiti Putra Malaysia Press. (Call no.: RSING 820.995957 SIN)

Leong, L.G. (1995). The poetics of history: Three women’s perspectives (pp. 433–442). In E. Thumboo & K. Thiru. (Eds.), The writer as historical witness: Studies in Commonwealth Literature. (Call no.: RSING 820.9917124 1120 WRI)

Leong, M. (1957). The air above the tamarinds: A collection of poems. Singapore: Eastern Universities Press. (Call no.: RCLOS 828.995957 LEO)

Leong, M. (1958). Rivers to Senang. Singapore: Eastern Universities. (Call no.: RCLOS 821.914 LEO)

Liew, G. (2000). Singapore: English literature (pp. 126–135). In Abdul Hakim Mohd. Yassin (Ed.), Modern literatures of ASEAN. Jakarta: ASEAN Committee on Culture and Information. (Call no.: RSEA 895.9 MOD)

Li, S.G-L. (1994). The national canon and English-language women writers from Malaysia and Singapore, 1949–1969 (pp. 158–202). In Writing S.E./Asia in English: Against the grain, focus on Asian English-language literature (pp. 158–202). London: Skoob Books Pub. (Call no.: RSING 828.9959 Lim)

Malayan spirit in her poems. (1958, December 23). The Straits Times, p. 26. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Margaret Leong – a woman with fascination. (1960, May 31). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Leong, M. (2011). The ice ball man and other peoms (pp. 10–11). Singapore: Ethos Books. (Call no.: JRSING 811 LEO)

Margaret Leong, 1921–2012. (2012, November 30). Columbia Daily Tribune. Retrieved from Columbia Daily Tribune website.

Nair, C. (1976). Review of Whitedream. Singapore Book World, 7, 21.

Nor Faridah Abdul Manaf & Mohamma A. Quayum. (2003). Colonial to global: Malaysian women’s writing in English 1940s–1990s. Kuala Lumpur: IIUM Press. (Call no.: RSEA 828.99595 NOR)

Ooi, T. (1984, April 23). Singapore artist makes a stir in London. The Straits Times, p. 27. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Ormerod, D. (1967). A private landscape. Kuala Lumpur, University of Malaya Library. (Call no.: RDET 828.995957 ORM)

Patke, R.S., & Philip. H. (2010). The Routledge concise history of Southeast Asian writing. London; New York: Routledge. (Call no.: RSING 895.9 PAT)

PEN America. (2013, April 24). Four poems by Wong May. Retrieved from PEN American website.

Peters, A. (1972, November 5). Geraldine wins yet another essay contest. The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Poetry Foundation. (2014). Wong May. Retrieved from Poetry Foundation website.

Puthucheary, R. (2012). My burning hill. Singapore: Ethos Books. (Call no.: RSING 821 PUT)

Puthucheary, S., & Puthucheary, R. (2008). Harvest of morning flowers. Singapore: Select Pub. (Call no.: RSING S821 TAN)

Tan, N. (1998). The collected poems of Nalla Tan (p. 111). Singapore: Times Books International. (Call no.: RSING S821 TAN)

Thumboo, E. (Ed.). (1976). The second tongue: An anthology of poetry from Malaysia and Singapore. Singapore: Heinemann Educational Books (Asia). (Call no.: RSING 828.995957 SEC)

Trope, L.R. (2009). Poetry on the brink: the indeterminate persona in the poetry of Lee Tzu Pheng (pp. 49–64). In E. Thumboo. (Ed.), Sharing borders: Studies in contemporary Singaporean-Malaysian literature. Singapore: National Library Board in partnership with the National Arts Council (Call no.: RSING S820.9 SHA)

University of Malaya in Singapore Literary Society. (1961– ). Focus. Singapore. (Call no.: 828.995957 F)

Wong, M. (1969). A bad girl’s books of animals. New York, Harcourt, Brace & World. (Call no.: RCLOS 828.99 WON)

Wong, M. (1972). Reports. New York, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. (Call no.: RSING 828.99 WON)

Yap. A. (2011). Closing my eyes to listen. Singapore: Landmark Books. (Call no.: RSING S821 YAP)

NOTES

-

Ee, T.H. (1987). History as myth in Malaysian poetry in English. In K. Singh (Ed.), The writer’s sense of the past: Essay on Southeast Asian and Australian literature (p. 10). Singapore: University Press. (Call no.: RSING 809.89595 WRI) ↩

-

Thumboo, E. (Ed.). (1976). The second tongue: An anthology of poetry from Malaysia and Singapore (pp. xxxii–xxxiii). Singapore: Heinemann, Educational Books (Asia). (Call no.: RSING 828.995957 SEC) ↩

-

Ormerod, D. (1967). A private landscape (pp. 9–10). Kuala Lumpur, University of Malaya Library. (Call no.: RDET 828.995957 ORM) ↩

-

Wong, M. (1969). A bad girl’s book of animals. New York, Harcourt, Brace & World. (Call no.: RCLOS 828.99 WON) ↩

-

Chan, F. (1999). Silences may speak: The poetry of Lee Tzu Pheng (p. 53). Singapore: Times Books International. (Call no.: RSING 828.995957 CHA) ↩

-

Patke, R.S., & Philip. H. (2010). The Routledge concise history of Southeast Asian writing (p. 123). London; New York: Routledge. (Call no.: RSING 895.9 PAT) ↩

-

Malayan spirit in her poems. (1958, December 23). The Straits Times, p. 26. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Dedicated poetry to son who hates it. (1956, December 8). The Straits Times, p. 20. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singh, K. (1987). Introduction. In K. Singh (Ed.), The writer’s sense of the past: Essay on Southeast Asian and Australian literature (p. xiii). Singapore: University Press. (Call no.: RSING 809.89595 WRI) ↩