Folk Tales from Asia

The Asian Children’s Literature collection at Woodlands Regional Library has some of the oldest and rarest children’s books from Asia. Lynn Chua highlights these treasures.

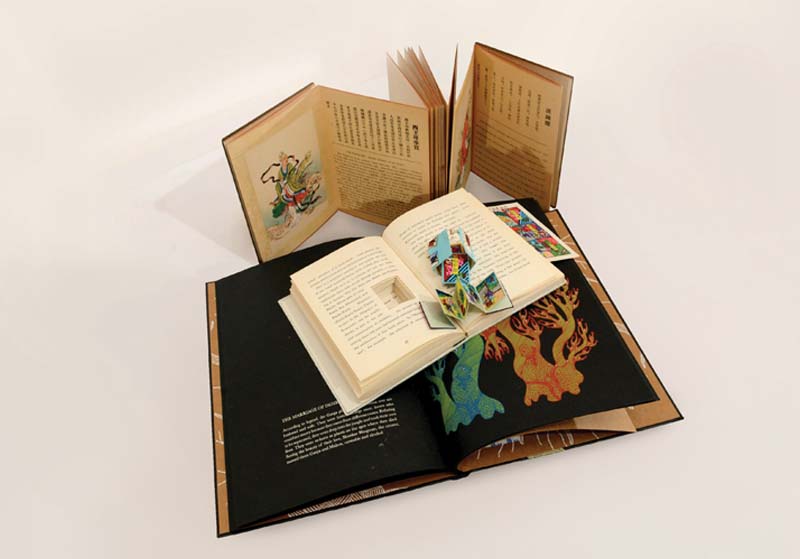

A selection of works found in the Asian Children’s Literature (ACL) collection at the Woodlands Regional Library. The 23,000-volume collection includes rare books that date back to the early 1900s.

A selection of works found in the Asian Children’s Literature (ACL) collection at the Woodlands Regional Library. The 23,000-volume collection includes rare books that date back to the early 1900s.Asia is the world’s largest continent in terms of population and area. With 49 countries spanning from China to Indonesia from north to south and Syria to Japan from east to west and containing over 60 percent of the world’s population, the Asian continent is home to a diverse variety of cultures with rich traditions and multi-layered histories.

Literature and art are the most common forms of cultural expression, and Asia, not surprisingly, is the birthplace of innumerable forms of folklore, mythologies and folk art. The National Library Board’s Asian Children’s Literature (ACL) collection features notable works of literature from the region, with many of its books featuring handmade elements and intricate artwork.

Carefully accumulated over time, the 23,000-volume ACL collection is housed at the Woodlands Regional Library. The collection of extremely rare books, some of which were produced in limited copies, offers a gateway into Asia’s rich cultures and its untold treasures. The collection is too large and disparate to document in a single article, so highlighted here are selected gems from India, Japan and China. It is hoped that these books will expose children to other cultures, piquing their curiosity and firing their imaginations.

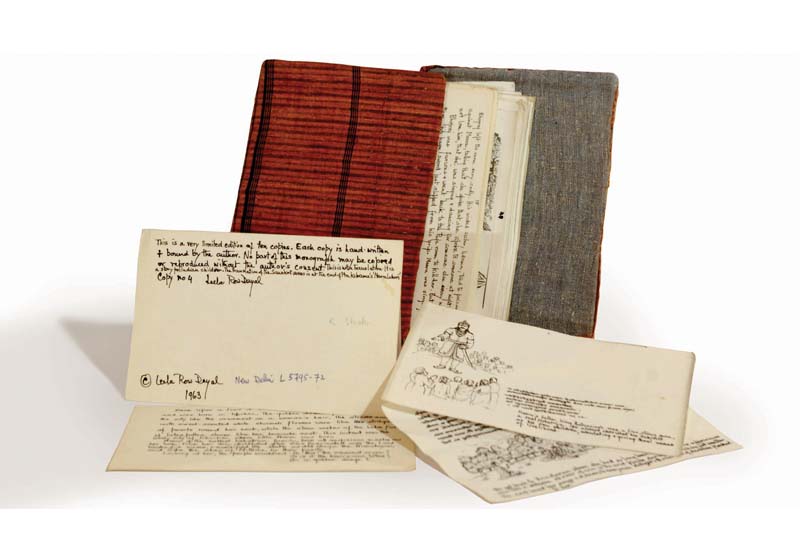

The copy of Princess Meera in the ACL collection. Published in 1963, only 10 copies of the book are available in the world.

The copy of Princess Meera in the ACL collection. Published in 1963, only 10 copies of the book are available in the world. Indian Handmade Books

Throughout history, every culture has made books, or the equivalent of what passes for books, with whatever materials they had at hand. Some communities would inscribe letters or symbols in clay that was then baked into a variety of shapes; others would create writing material crafted from plants and animal hides.

Over the last century, industrial production has steadily replaced traditional handmade means of book making. What is interesting, however, is that while modern technology and the invention of the printing press have made it possible to produce books more efficiently and in large quantities, there are places in the world where books are still being made by hand, using natural resources and time-honoured techniques passed down from one generation to another.

In parts of India, there is a strong tradition of products made by traditional crafts people using simple, indigenous tools. The range of Indian art and handicrafts is as rich and varied as the people who live in the subcontinent. Despite the march of time, the unique craft of handmade books is still very much alive in India today. The Night Life of Trees, In the Dark and The Very Hungry Lion are some examples of handmade books from India, using paper made from a mixture of cotton cloth remnants, tree bark, rice husks or grass.

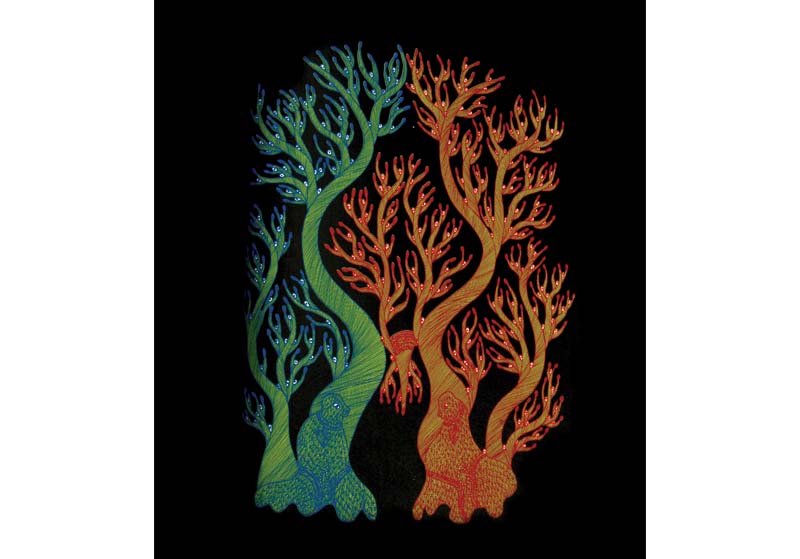

The Night Life of Trees, published in 2012, is a handmade book that reflects the art of three Gond (a Dravidian people who live in central India) artists: Ram Singh Urveti, Bhajju Shyam and Durga Bai. Painstakingly silk screened by hand, each spread showcases an intricate drawing of a sacred tree along with an explanation of its significance to the community. Each image is a tribute to the Gond community’s animist belief in trees, giving readers an insight into the spirituality of the Gond people, and their perception of nature and the cosmos.

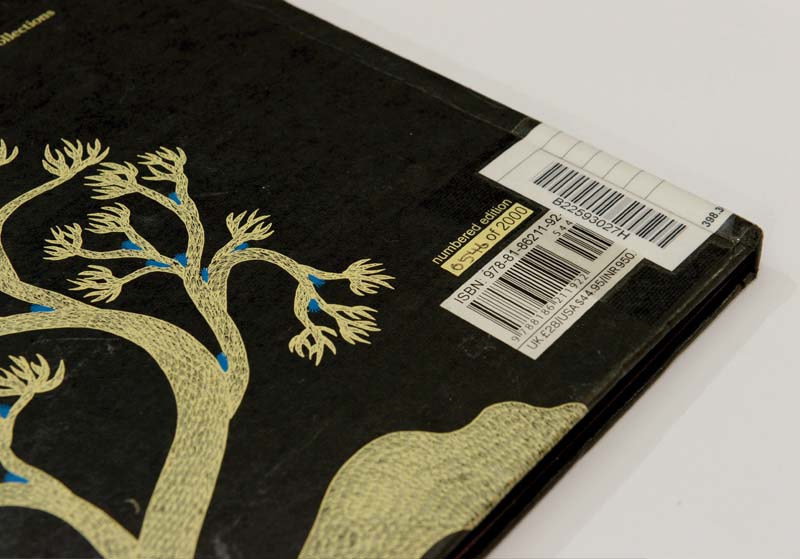

About 100 pulls of the screen are required to print each copy of the 32-page book. A print run of 2,000 copies would require about 200,000 pulls of the screen by hand, an indication of the immense time and effort to print these books. In addition, the books are hand-bound, a process that involves punching holes with a mallet and nail and hand-stitching the pages together.

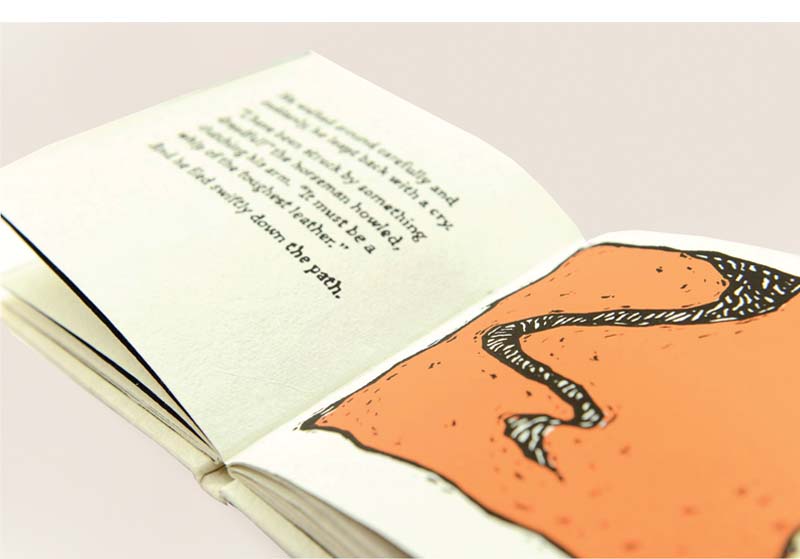

A peek into a page of The Night Life of Trees. One Gond legend featured is that of the Ganja plant and the Mahua tree. Believed to be humans before they turned into trees, they were lovers who could not marry because they belonged to different castes. Refusing to be separated, the couple took their lives somewhere deep in the forest and were reborn as plants on the spot where they died.

A peek into a page of The Night Life of Trees. One Gond legend featured is that of the Ganja plant and the Mahua tree. Believed to be humans before they turned into trees, they were lovers who could not marry because they belonged to different castes. Refusing to be separated, the couple took their lives somewhere deep in the forest and were reborn as plants on the spot where they died. Every copy of The Night Life of Trees is numbered by hand. This particular book is the 546th copy out of 2,000.

Every copy of The Night Life of Trees is numbered by hand. This particular book is the 546th copy out of 2,000.Another example of a handmade book is Princess Meera. Published in 1963, this is one of the most treasured possessions in the Asian Children’s Literature collection. It is handwritten and bound by the author herself. Author Leela Row Dayal used line drawings to illustrate the story of Meerabai, a Hindu princess and mystical singer of sacred songs, based on Pandita Kshama Rao’s Sanskrit poem (the Sanskrit verses are included in their original form in the book). In the book, Princess Meerabai – who is known for her devotion to Lord Krishna – is born in the city of Khurkhi and hails from a noble kshatriya, or warrior family.

In the Dark is a traditional Sufi tale of wisdom. This book is calligraphed and screenprinted on handmade paper.

In the Dark is a traditional Sufi tale of wisdom. This book is calligraphed and screenprinted on handmade paper.Japanese Woodblock Prints

llustrations of Japanese literature typically feature woodblock colour-printing called ukiyo-e, one of the most famous traditional Japanese art forms.

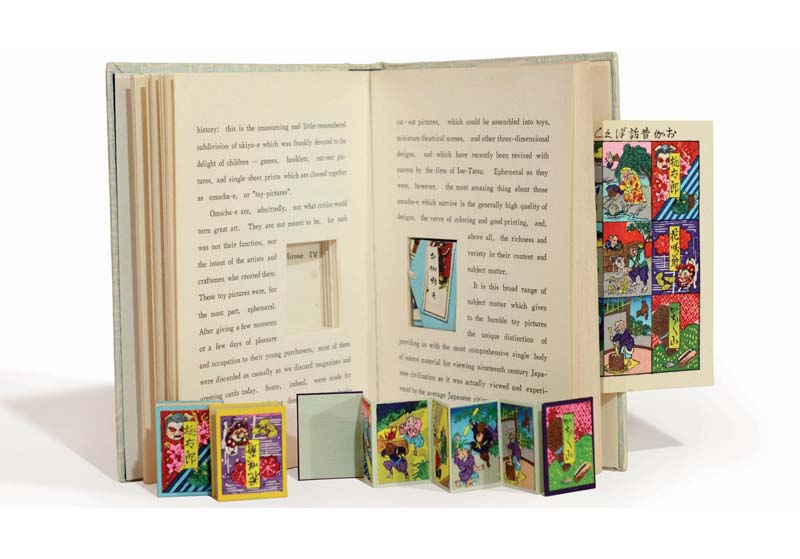

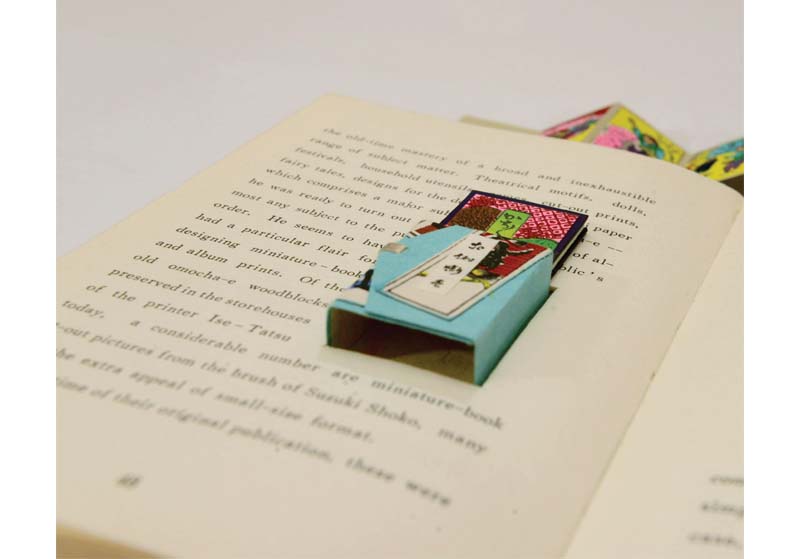

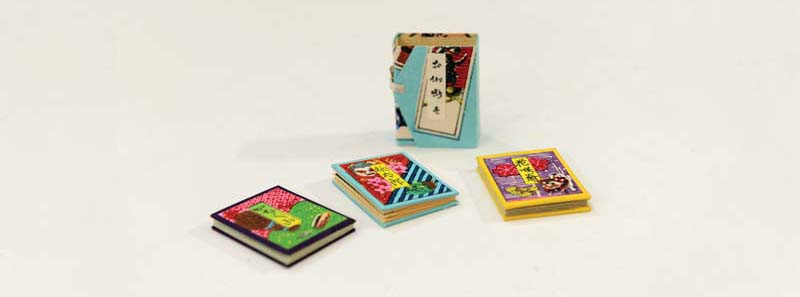

The beauty of woodblock prints can be seen in Otogi-Banashi, a bilingual title packaged as an old-style toy book, which combines concepts of learning with play and serves as an educational toy for children as well. Relatively few specimens in good condition exist today as, in many cases, these toy books were literally read to pieces.1

The craft of toy books were originally created as playthings for Japanese children. Three Japanese folktales are featured in this volume: The Old Man Who Makes the Flowers Bloom, Momotaro and KachiKachi Mountain. The binding and outer slipcover for this particular volume is made of chiyogami, a traditional Japanese paper characterised by its hand-stencilled and block-printed patterns.

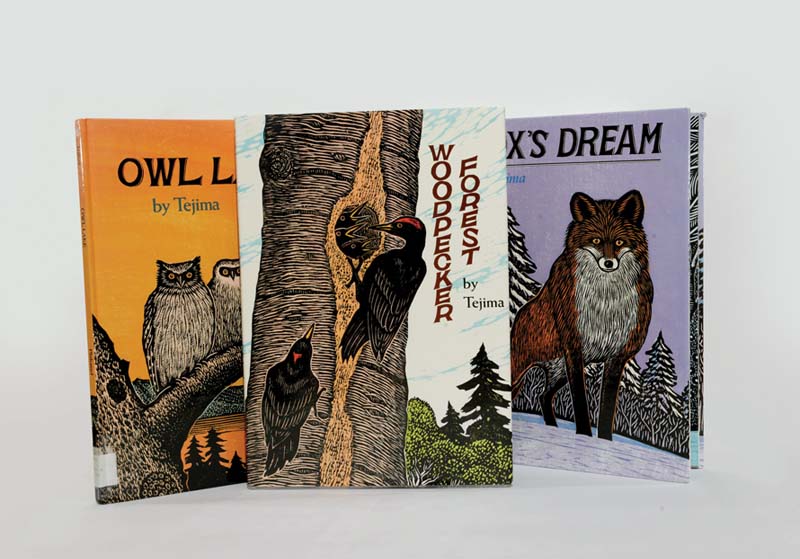

For more recent works featuring woodblock prints, award-winning artist Keizaburo Tejima comes to mind. Born in 1935, he was one of the few Japanese artists working with the woodblock technique used in children’s books in the 1980s. His books were published in 1986 in North America where he gained recognition as a prominent author and illustrator. Owl Lake and Fox’s Dream were on the American Library Association (ALA)’s list of Children’s Notable Books, and the New York Times listed Fox’s Dream as one of 1987’s 10 best illustrated books. His books are still popular today.

The uniqueness of Otogi-Banashi lies in its accompanying miniature books and book-within-a-book format. The miniature books contain only illustrations. The bigger book provides captions to the miniature books and an introductory essay to the history of toy books and woodblock prints.

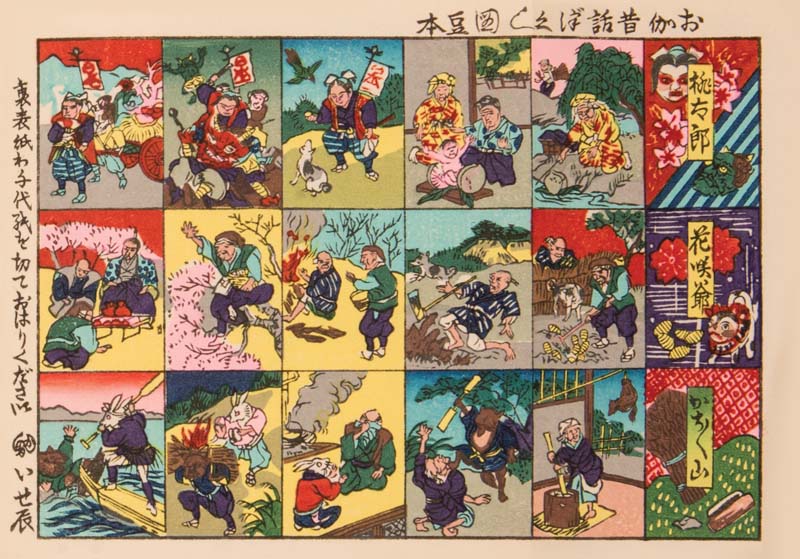

The uniqueness of Otogi-Banashi lies in its accompanying miniature books and book-within-a-book format. The miniature books contain only illustrations. The bigger book provides captions to the miniature books and an introductory essay to the history of toy books and woodblock prints. Otogi-Banashi. This specimen of an uncut single-sheet print found in OtogiBanashi includes the heading “Fairy tale pictures for a toy book”, with brief instructions in the left margin on how to turn the pictures into miniature books. The illustrations here and in the three miniature books contained in this single volume were printed by hand using the original wood blocks from the publisher’s own collection.

Otogi-Banashi. This specimen of an uncut single-sheet print found in OtogiBanashi includes the heading “Fairy tale pictures for a toy book”, with brief instructions in the left margin on how to turn the pictures into miniature books. The illustrations here and in the three miniature books contained in this single volume were printed by hand using the original wood blocks from the publisher’s own collection.

The woodblocks used to print the omocha-e (toy pictures) in Otogi-Banashi were cut during the Taisho period (1912–1926). By a fortunate shift in location, the woodblocks escaped the bombing that destroyed most of Tokyo during World War II. Just before the war, the well-known printing house of Ise-tatsu moved from Kanda to the historic area known as Yanaka. This was one of the few areas of Tokyo that escaped the bombings. As Hirose Tatsuguro remarks, it was a stroke of luck that the woodblocks of one of the last publishers of traditional children’s books and omocha-e survived. The war saw the loss of private collections of omocha-e owned by children. As few museums or libraries had thought of collecting these toy books, their loss was irreparable.

The woodblocks used to print the omocha-e (toy pictures) in Otogi-Banashi were cut during the Taisho period (1912–1926). By a fortunate shift in location, the woodblocks escaped the bombing that destroyed most of Tokyo during World War II. Just before the war, the well-known printing house of Ise-tatsu moved from Kanda to the historic area known as Yanaka. This was one of the few areas of Tokyo that escaped the bombings. As Hirose Tatsuguro remarks, it was a stroke of luck that the woodblocks of one of the last publishers of traditional children’s books and omocha-e survived. The war saw the loss of private collections of omocha-e owned by children. As few museums or libraries had thought of collecting these toy books, their loss was irreparable.  Often featured in flight with his expansive wings spanning entire two-page spreads, Father Owl’s magnificence is undeniable. As Father Owl swoops down on his unsuspecting prey, the scene is sharply framed by the angled white space at the bottom of the spread, creating an optical illusion by emphasising the exhilaration and immediacy of the catch. Dramatic woodcut illustrations and the clever use of diagonal lines in Owl Lake bring alive the story of an owl and its family’s search for food.

Often featured in flight with his expansive wings spanning entire two-page spreads, Father Owl’s magnificence is undeniable. As Father Owl swoops down on his unsuspecting prey, the scene is sharply framed by the angled white space at the bottom of the spread, creating an optical illusion by emphasising the exhilaration and immediacy of the catch. Dramatic woodcut illustrations and the clever use of diagonal lines in Owl Lake bring alive the story of an owl and its family’s search for food. Three of Keizaburo Tejima’s books from the Asian Children’s Literature collection – Owl Lake, Woodpecker Forest and Fox’s Dream. One of Tejima’s purposes was to transport the reader to Hokkaido, his birthplace, to observe the wildlife and to showcase the island’s natural beauty through his works. He used a tinted woodblock technique which he sometimes supplemented with brush-on paint. This traditional form allows for a good deal of texture in solid blocks of colour as well as very strong, bold lines.

Three of Keizaburo Tejima’s books from the Asian Children’s Literature collection – Owl Lake, Woodpecker Forest and Fox’s Dream. One of Tejima’s purposes was to transport the reader to Hokkaido, his birthplace, to observe the wildlife and to showcase the island’s natural beauty through his works. He used a tinted woodblock technique which he sometimes supplemented with brush-on paint. This traditional form allows for a good deal of texture in solid blocks of colour as well as very strong, bold lines.China, Bookbinding and Papercuts

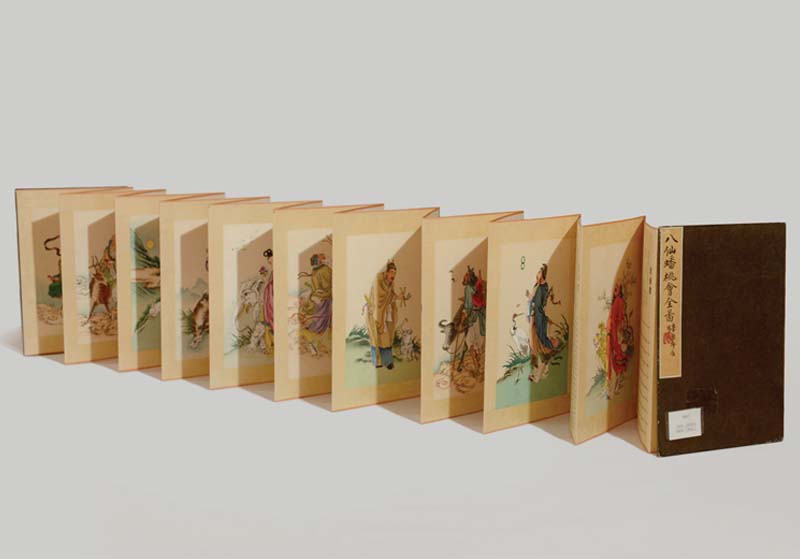

No one would dispute the importance of books and the written word in China. Few cultures in the world have enjoyed such a long and chequered tradition of literary production. Different kinds of Chinese bookbinding have been documented throughout history, many of them unique to China, including stitched binding, accordion binding and Chinese pothi binding.

Accordion bookbinding is where the book is bound only to the front and back case boards with one long sheet between them, folded to demarcate pages. Accordion books were traditionally used as a vehicle for Buddhist sutras. For this reason, it was named “jingzhe zhuang,” which means “folded sutra binding”. By the late Tang Dynasty (AD 618–907), the accordion format of books had been widely adopted by Buddhists in China. Accordion bookbinding was said to have evolved from Chinese scrolls.2

Pang Tao (Flat Peaches): Eight Fairies Festival. The accordion book resembles a scroll when not folded. The transformation from Chinese scroll to accordion can be made by folding the scroll to form separate folios. Unlike scroll books, which are awkward to unroll whenever one needs to examine a particular section of text, the accordion format makes it easier for the reader to sift through the text.

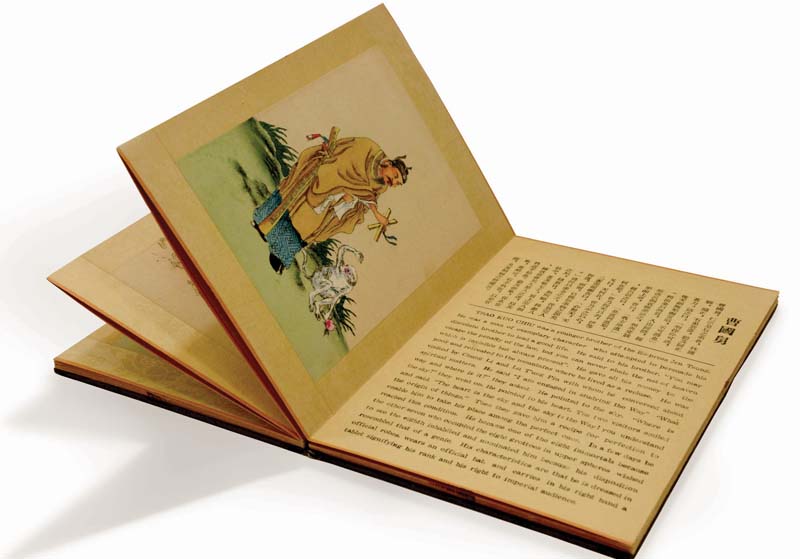

Pang Tao (Flat Peaches): Eight Fairies Festival. The accordion book resembles a scroll when not folded. The transformation from Chinese scroll to accordion can be made by folding the scroll to form separate folios. Unlike scroll books, which are awkward to unroll whenever one needs to examine a particular section of text, the accordion format makes it easier for the reader to sift through the text.Pang Tao (Flat Peaches): Eight Fairies Festival (1900–1950) is one of the few titles in the ACL collection that is bound in an accordion format. Pang Tao is a Chinese folktale that portrays these legendary characters: Hsi Wang-Mu, renowned for her famously sweet and delicious pang tao (peaches), and the legendary Eight Immortals of Chinese mythology. This bilingual book (English and Chinese) tells of the origins of the immortals and how they embarked on their journeys towards deity-hood.

The eight hand-coloured plates of the legendary immortals framed in silk brocades in Pang Tao (Flat Peaches): Eight Fairies Festival breathe life into the characters and story.

The eight hand-coloured plates of the legendary immortals framed in silk brocades in Pang Tao (Flat Peaches): Eight Fairies Festival breathe life into the characters and story.The traditional style of papercutting is also typical of Chinese culture. The art of cutting paper designs in China developed during the Han and Wei periods before iron tools and paper were even invented. Papercutting is a technique of cutting an image out of paper. The final image is formed by the contrast of the solid parts that remain and the negative spaces that have been cut out. Legend has it that Emperor Wu of the Han Dynasty (156–87 BC) missed Lady Li, his favourite concubine who had died, so much that he had a figure of her carved in hemp paper to summon her spirit back. This was perhaps the earliest mention of a papercut.3

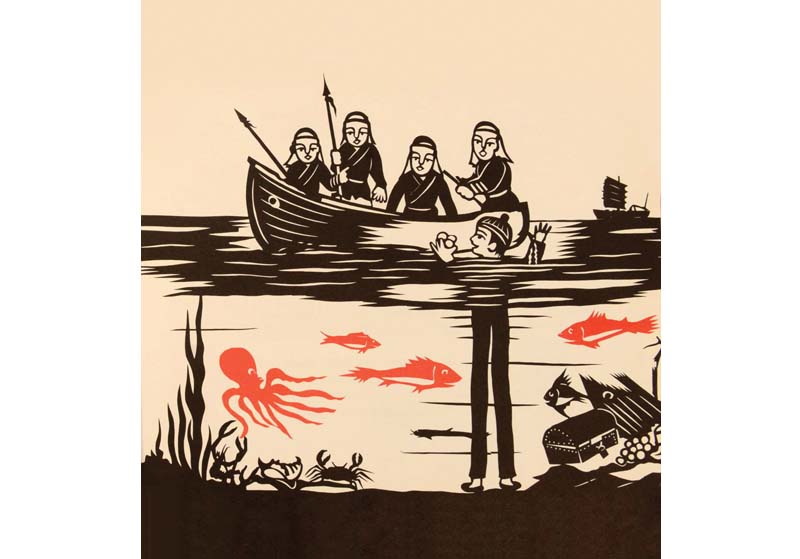

During the Ming and Qing dynasties, the art of papercutting reached its peak. The technique was applied for embellishing folk lanterns, fans and embroidered fabrics. Today, papercutting remains a very popular folk art, a distinctive feature of Chinese culture and is commonly used for decorations. Papercutting is also used to illustrate Chinese literature. In Six Chinese Brothers, published in 1979, the author Cheng Houtien brings the ancient tale to life with red and black papercut illustrations using the scissor cutting technique.

In Chinese literature, papercut illustrations are used to depict famous scenes from popular legends that emphasise moral lessons and celebrate epic characters, providing a visual means to introduce Chinese art and culture to children during storytelling. As papercut illustrations combine folktales with art, they act as visual reminders of the beliefs and values of a people.

The books featured in this article offer just a tiny sampling of the treasures available in the Asian Children’s Literature collection. The stories contained within these books, when shared with our young generation, will help them understand their own ancestral cultures, traditions and values as well as that of the larger Asian world we live in.

An ancient Chinese tale of six brothers, each with a special trait, Six Chinese Brothers is popular legend that has been written and told in many variations – in some versions, there are 10 brothers instead of six.

An ancient Chinese tale of six brothers, each with a special trait, Six Chinese Brothers is popular legend that has been written and told in many variations – in some versions, there are 10 brothers instead of six. Lynn Chua is a Senior Librarian with the National Library Board (NLB). She was in charge of developing the Asian Children’s Literature collection at the Woodlands Regional Library in 2012, and making the collection available to a range of users such as researchers, teachers, parents and students. She has also initiated programmes and led librarians in curating exhibitions that cultivated interest in reading and appreciation of Asian culture and heritage.

REFERENCES

Wolf, G. (1969). The Very Hungry Lion: A Folktale. Madras: Tara Pub. (Call no.: JL 398.2 WOL)

The Night Life of Trees. (2012). Chennai: Tara Books. (Call no.: RSING 398.368216053 SHY); The night life of trees. (2006). Chennai: Tara Books. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Tara Books. (n.d.). Handmade book. Retrieved from tara books website.

Cheng, H.T. (1979). Six Chinese brothers: An ancient tale. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Dayal, L.R. (1963). Princess Meera. New Delhi: L.R. Dayal. (Call no.: RACL 398.210954 DAY)

Marks, A. (2010). Japanese Woodblock Prints: Artists, publishers, and masterworks, 1680–1900. Rutland, VT.: Tuttle Pub. (Call no.: RART 769.952 MAR)

Pang tao = Flat peaches : eidht [i.e. eight] fairies festival. [n.d.]. [Shanghai?: Publisher not identified]. (Call no.: RACL 398.20951 PAN)

Ranjan, A., & Ranjan, M.P. (Eds.). Handmade in India: A geographic encyclopaedia of Indian handicrafts. New York: Abbeville Press. (Call no.: RART 745.0954 HAN)

Schmidt, G.D. (1990, December). The elemental art of Keizaburo Tejima. The Lion and the Unicorn, 14 (2), 77–91.

Tatsugoro, H. (1969). Otogi-Banashi. Tokyo: Ise—Tatsu. (Call no.: RACL 398.20952 HER)

Tejima, K. (1987). Owl lake. New York: Philomel Books. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Tejima, K. (1987). Fox’s dream. New York: Philomel Books. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Tejima, K. (1989). Woodpecker forest. New York: Philomel Books. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Wolf, G., & Rao, S. (2000). In the dark. India: Tara Pub. (Not available in NLB holdings)

NOTES

-

Tatsugoro, H. (1969). Otogi-Banashi. Tokyo: Ise—Tatsu. (Call no.: RACL 398.20952 HER) ↩

-

Chinnery, C. (n.d.). Bookbinding. Retrieved from The International Dunhuang Project: The Silk Road website. ↩

-

Knapp, R.G. (2011). Things Chinese: Antiques, crafts, collectibles. VT: Periplus Editions, North Clarendon. (RART 745.0951 KNA-[ART]) ↩