Suratman Markasan: Malay Literature and Social Memory

Azhar Ibrahim examines how the illustrious Malay writer Suratman Markasan uses literature as a means to propagate ideas and mark signposts in our social memory.

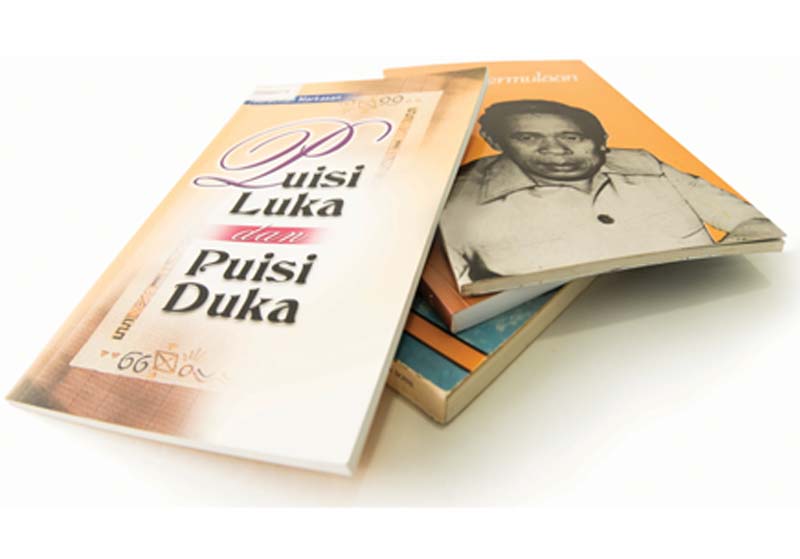

Suratman Markasan is considered as one of Singapore’s literary pioneers. Image courtesy of Tribute.sg, an initative by Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay.

Suratman Markasan is considered as one of Singapore’s literary pioneers. Image courtesy of Tribute.sg, an initative by Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay.And so everyone made the assumption that the news had been barred from publication, because it was feared that such news would have a negative impact on the development of the minds of the younger generation. The truth is, there are men of all natures. So there was yet another assumption that the reporting of such news had been prevented because it would have a negative impact on the development of the nation and its people, or more specifically, on the formation of mainstream thoughts and minds.”

Suratman Markasan was born in 1930 in Pasir Panjang, Singapore. After completing his studies at Sultan Idris Training College (SITC) in Perak (Malaysia) in 1950, he joined the teaching service and in 1968 enrolled in Nanyang University, graduating three years later with a degree in Malay and Indonesian Studies. He was appointed as Assistant Director for Malay and Tamil studies at the Ministry of Education and following that, lectured at the Institute of Education until 1995. His literary career spans from the early 1950s right up to the present. In 1989, Suratman received the SEA Write Award from the Thai monarch1 and in 2010, was awarded Singapore’s prestigious Cultural Medallion for Literary Arts.

Suratman is a respected figure in modern Malay literary history. He is a Singapore writer through and through, exemplified in many of his works, both verse and prose. His literary repertoire encompasses three main areas: social critiques, with morality and ethics as the main criteria for evaluating ideas, values and practices; the observation of the social, cultural and political changes that have impacted Malay society; and the clamour for religious reforms and the return to religion in the midst of vast changes taking place in modern society. To Suratman, religion and ethics are essential tools to address the dehumanisation of thought and practices in society.

Suratman wrote his first poem “Hati Yang Kosong” (An Empty Heart) in 1954, recounting his pursuit of finding meaning in life. His collection of poems, recently compiled into a single volume,2 portrays the vista of his poetic concerns, talent and commitment. His concerns are primarily social ones, in line with his background as an educator. He believes in using the literary medium to raise awareness of issues, or at least to document his perspectives and sentiments on matters that he has witnessed or experienced. But Suratman’s poetic repertoire is not limited to social issues; he has written a fair number of poems on the subject of love, in particular, the ones he wrote for his late wife, Saerah Taris.3 Suratman has also written novels,4 short stories, poems, essays, and literary essays as well as compiled two anthologies of short stories and poems of selected Singapore writers.5

Defining Social Memory

By social memory, we mean the act and will of documenting the cultural experiences that a community has undergone, especially where changing political, social and economic contexts have posed serious challenges to such memory. It is not too far fetched to posit that a country’s literary and cultural intelligentsia are the guardians of social memory.6 Literature is a medium that records, articulates and reimagines social memory; thus, literary works become important sources that document aspects of our social and historical lives. This is especially significant when a community’s historical experiences and voices are marginalised and not captured in the dominant, mainstream historical narratives of the country.

Thus, Malay literary works such as Suratman’s are important sources that we can draw upon as social memory, albeit through literary imagination. In this regard, Suratman’s contributions to the literary scene cannot be underestimated. His works are set against a primarily Singapore background, with characters and themes that local readers can relate to. The themes in turn reflect Suratman’s response to the social, political, economic and cultural norms of both society and nation.

The Local Literary Landscape

Suratman wrote in the context of a hegemonic social and cultural discourse where critical and dissenting sentiments were deemed as chauvinistic, subversive or sometimes even extremist. This created an environment where the general public became adverse to critical or political works and where even writers themselves would ironically impose self-censorship in order to avoid direct conflict with those in power. However, it is through literature that dissenting ideas can be articulated via literary allegories and symbolism. Thus, oblique criticisms could be made without direct confrontation with the powers that be.

However, oftentimes the intended meaning of the writer might be lost on his audience, particularly one that might be politically apathetic due to an underdeveloped socio-cultural literacy. In general our readings of literature are rarely critical, in search of aesthetic pleasure rather than confronting the politics of literature. Also, the reading public and literary studies in our education system are very much divorced from the idea of the link between literature and society. With formalistic reading and aesthetic criticism dominating literary scholarship, our understanding of the role of ideas in literature is further inhibited.

Literary Ideal and Aspiration

Suratman writes not for recognition or revenue. His primary purpose is to propagate ideas for the reading public to consider. His dedication to the Malay literary world is affirmed by his conviction that literature has the role of developing men and women who become conscious, through the reflection and appreciation of beauty and truth, to challenge the accepted norms, or to deliberate on issues that are deemed as taboo. As a literary figure who has been present during the major milestones of Singapore’s literary history, Suratman is someone who sees and has seen the development of Singapore’s literary landscape.

As a national literary pioneer, his body of work, built over the years, tracks the maturing of his thoughts, the improvement of his writing craft and style, and the themes he explores. Overall Suratman is a modernist writer, writing with a reformist bent, uniquely positioned to speak for his community in a modern multicultural society. Suratman’s works advocate reform, calling for progress and change, pointing clearly at those who are ambivalent to the communities’ predicaments. As a language teacher, Suratman is critical that vernacular languages, namely, Malay, Tamil and Mandarin are being sidelined in favour of English. He also examines issues such as the elite’s abandonment of responsibility towards ensuring the welfare and dignity of his community.

Literary Engagement

Suratman is a dedicated commentator of the current social climate. As a keen observer of ordinary experiences, Suratman’s works document the social life of his community, especially the challenges it faces in an urban setting. But this does not make him any less a literary craftsman. He does not subscribe to any particular philosophy, nor does he champion a specific agenda. His mastery lies in crafting simple short stories that are easily understood. His collections of poems are loaded with social criticisms as well as fragments of his personal experiences.

In general, his works record the challenges and turbulence of urban life. He embraces the view that literature is a platform for social and cultural enlightenment, aimed at guiding his community in the transition from traditional to modern society. Suratman is also a narrator of past experiences, or the recent past to be more precise. This is where several of his works have encapsulated the theme of social memory. This idea can be classified into three main themes.

Economic development in Singapore in the 1960s and 70s led to the relocation of Malays from their traditional community spaces. Pictured here are Malays living on one of the southern islands on public assistance welfare in 1961. MITA collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Economic development in Singapore in the 1960s and 70s led to the relocation of Malays from their traditional community spaces. Pictured here are Malays living on one of the southern islands on public assistance welfare in 1961. MITA collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.His literary works, firstly, present social commentaries on the Malay community, criticising what he feels to be undesirable actions or ideas. His creative works, both in prose and verse, are complemented by his essays on culture, religion and language. Secondly, Suratman presents himself as a family man, both as father and husband. Thirdly, his works affirm his spiritual and religious convictions.

Suratman often writes about themes commonly expressed by the Singapore Malay community. He attempts to engage his readers to think about the issues raised, encouraging them to contemplate their existential and social conditions. These issues include parental neglect, spiritual emptiness, cultural alienation, language deprivation, the plight of the poor, the leadership crisis in the Malay community and the mismanagement of mosques.7

His poetry considers several aspects of social memory such as his memory of physical spaces that used to be part of his life, and which have now disappeared. This is captured in his poem on his alma mater, Sultan Idris Training College. One recurring reference in his poems is Tun Seri Lanang Secondary School, a Malay-medium school whose establishment was a seen as a triumph for Malay education in Singapore. When the school was formed in 1963, Suratman described the joy he felt: “apparently Seri Lanang was born beside Kallang River/ all the Malays who were supportive were joyous” (ternyata lahir Seri Lanang di tepi Sungai Kallang/ segala Melayu yang suka menatang gembira). 8 But by 1989, these Malay-medium schools were closed as enrolment fell drastically, with Malay families preferring to send their children to English-medium schools instead. Suratman lamented:

negara Seri Lanang kian pudar di mata Mat layu / pelajar tinggal sedikit guru menjadi buntu / di sana sini orang bercakap Inggeris tentu / biar dianggap punya pelajaran tinggi / atau di kedai kopi yang tak memerlu degree / Melayu sudah lesap Inggeris belum lengkap / pada detik yang bernama 1987 / Tun Seri Lanang mengikuti jejak Sang Nila Utama / tak terduga tenggelam di Sungai Sejarahnya.9

the state of Seri Lanang was fading in the eyes of Mat Layu / students were getting fewer, teachers were at their wits’ end / hither and thither people spoke English for certain / in order to be deemed as highly educated / even in coffee shops that didn’t need a degree / Malay was gone, English was yet to take over completely / in the year called 1987 / Tun Seri Lanang followed the footsteps of Sang Nila Utama / unexpectedly sank in Historical River.

Again in another poem, “Masih Adakah Melayu di Sini?” (Will Malays Still be Around?)

Nila Utama dan Seri Lanang sudah tenggelam / satu di bidadari satu di Sungai Kallang / Swiss Cottage sudah hilang Cottagenya / Pasir Panjang Monk’s Hill dan Siglap / sudah terkubur tanpa nisannya / anak dan cucu mereka sudah hilang jati dirinya / itulah nasib peribumi Melayu namanya10

Nila Utama and Seri Lanang are sunken / one in Bidadari, another at Kallang River / Swiss Cottage has lost its Cottage / Pasir Panjang, Monk’s Hill and Siglap / are now buried without a tombstone / their children and grandchildren have lost their identity / that’s the fate of the Malay natives

Suratman laments the loss of the past not so much because he was romanticising it, but because he felt that in keeping pace with changing times, the way in which progress and development affected people on the ground was overlooked. Only a perceptive poet like Suratman could capture the sentiments of those affected by these changes, giving their struggles a voice and form:

Laut tempatku menangkap ikan / bukit tempatku mencari rambutan / sudah menghutan dilanda batu bata, / Pak Lasim tak bisa lagi menjadi penghulu / pulaunya sudah dicabut dari peta kepalanya / anak buah sudah terdampar / di batu-bata dan pasir-masir hangat.11

The sea where I caught fishes / the hill where I looked for rambutans / have turned into a jungle swarmed by bricks, / Pak Lasim can no longer be a headman / his island has been uprooted from his mind / his kinsmen have been marooned / on hot bricks and sand

These lines refer to the Southern islanders who were forced to resettle on mainland Singapore. Suratman empathised with their plight, as their loss was also his:

Aku kehilangan lautku / aku kehilangan bukitku / aku kehilangan diriku.12

I have lost my sea / I have lost my hill / I have lost my self

The close knit village community is gone. Suratman remembers the small village and all its residents; he knows them personally without needing to differentiate between a Malay and Chinese person. This is illustrated in “Dalam Perjalanan Masa,” (With the Passage of Time):

Ketika aku masih kecil / banyak yang aku tahu / kerana duniaku sesumpit kampungku / peduduknya kuhafal dalam kepala / aku kenal mereka bukan kenal Cina / daun-daun gugur bisa tertangkap mata13

As a little child / I knew a lot / as my world was as narrow as my village / the villagers were entrenched in my mind / I knew them all, not casually? / falling leaves can be caught by the eye

Suratman is especially sensitive to junctures in Singapore’s history where social memory is both affirmed and denied. In “Balada Seorang Lelaki Di Depan Patung Raffles” (The Ballad of a Man Before the Statue of Raffles) Suratman describes a mad man who posed questions before the statue of Sir Stamford Raffles, founder of modern Singapore. The insane man who railed at the statue of Raffles can be seen as representative of the indigenous man who became a victim of colonialism. In another poem, Suratman challenges the dominant historical narrative, reminding the reader that the victims of colonialism are his own people:

Telah kukatakan seribu kali / kau menipu datukku hidup mati / kau merampas hartanya pupus rakus / kau bagikan kepada kawan lawan / kau dengar Raffles? Kau dengar? / seharusnya kau kubawa ke muka pengadilan.14

I’ve said it a thousand times / you deceived my grandparents totally / you seized their properties till it’s gone, greedily / you gave it away to your friends, enemies / do you hear, Raffles? Do you hear? / I should have brought you to face justice

The questioning of history by this mad man reminds us of the weapons of the weak in their confrontation with the dominant power. The fight may be futile, but the sentiment reflects the angst of humiliation and the struggle to resist it. The weak may have no power to challenge authority, except with words of affirmation of their dignity and rights. Thus the mad man’s curse on the two colonial figures (Raffles and William Farquhar) is the objection to history by the very people who have been denied in history.

Dosamu tujuh turunan kusumpah terus / kau membawa Faquhar dan Lord Minto / siasatmu halus. Membuka pintu kotaku / pedagang buruh pemimpin menambah kantung / membangun Temasek menjadi Singapura / masuk sama penipu perompak pembunuh / aku sekarang tinggal tulang dan gigi cuma / kusumpah tujuh turunanmu tanpa tangguh!15

Your sins for seven generations I put a curse on / you brought with you Farquhar and Lord Minto / your intelligence was subtle. By opening my city doors / traders, labourers, leaders filled up their pockets / they developed Temasik into Singapore / swindlers, robbers, murderers all entered too / I’m now left with only bones and teeth / I curse you for seven generations now!

Suratman again challenges the dominant historical narrative in another poem:

di sekolah aku diajar ilmu sejarah / Raffles menemui Singapura / raja mendapat kekayaan menjadi besar empayarnya / sultan mendapat wang menjadi gemuk tubuhnya / pendatang bertambah hidupku tak berubah16

At school, I was taught history / Raffles founded Singapore / the king gained riches, his empire expanded / the sultan received money, his body became plump / immigrants increased, my life remained the same

In a country where modernisation and progress is celebrated, we forget that there are some things that are lost in the process of attaining these goals. The cultural life of the people is one realm where this loss is most significantly felt:

Aku berjalan di pesisir Geylang / terpekik-pukau raja kuih / tak kutemui kuih Melayu / melambak biskut dan cookie / aku terdorong ke Kampung Melayu / tapi ibu dan anak tak berbahasa Melayu / aku mencari baju kurung teluk belanga / yang kutemui cekak musang berkancing cina17

I walked along the sidewalk in Geylang / the king of kuih was hollering / I didn’t find Malay kuih / but plenty of biscuits and cookies / I was prompted to go to the Malay Village / yet, a mother and her child there didn’t speak Malay / I was looking for a teluk belanga baju kurung / what I found was cekak musang baju with Chinese buttons

The phenomenon of levelling down cultural standards and excellence in our modern fast-paced society is a state of affairs that Suratman bemoans. Cultural sensibilities are lost alongside the fading memories of the past. With cultural amnesia comes historical amnesia. The younger generation, Suratman notes, has lost its reverence for Malay historical figures:

pahlawan Nila Utama kurang disanjung pendekar Melayu / penulis Seri Lanang berdiri termangu menunggu budak Melayu18

the warrior Nila Utama was hardly celebrated by Malay fighters / the writer Seri Lanang stood puzzled waiting for Malay students

Suratman has produced a large body of work, with themes that cover issues such as race and nationhood. All rights reserved, National Library Board Singapore, 2014.

Suratman has produced a large body of work, with themes that cover issues such as race and nationhood. All rights reserved, National Library Board Singapore, 2014.Suratman, however, clearly remembers the Malay historical figure whose actions precipitated the plight of his people:

dan lupa daratan Sultan Husin Syah juga / ditambah tipu muslihat Raffles Farquhar / tergadai sudah Singapura ke tangan Inggeris 19

and Sultan Husin Syah’s insensible of his place / plus the ruses of Raffles and Farquhar / Singapura was pawned into the hands of the British

The decisions of past Malay leadership are responsible for the fate of Malays today. But Suratman is equally vehement against the present Malay leadership, particularly their ambivalence towards and negligience in promoting the Malay language:

di sini sana orang bercakap Inggeris tentu / baik di rapat MUIS atau MENDAKI maju / biar pun di gerai Geylang si Mat Layu yang baru 20

hither and thither people spoke English for certain / either in MUIS or MENDAKI meetings they went on / even at the new stall of Mat Layu in Geylang

Here, Suratman, who is passionate about the Malay language, laments the diminishing presence of the once dominant language in Singapore. The post-separation era saw the language disappear from the mainstream, compounded by the closure of Malay schools:

Aku tak punya apa lagi / Seri Lanang dan Nila Utama tinggal nama / saudara peribumi menolak bahasa / mengejar Inggeris lambang kemajuan. 21

I no longer have anything / Sri Lanang and Nila Utama remain names / my native siblings have rejected the Malay language / they are pursuing English as a symbol of progress

Suratman’s works, especially his poems, capture a variety of memories that he encountered and perceived as well as imagined. His personal recollections of the past are in themselves a rich of source of the lives that are no longer part of our collective memory. In his poem, “70 Tahun Usiaku” (The Seventienth Year of My Life), he charts each decade of his life, noting his experiences in witnessing unfolding history.

He starts his first decade with his basic education and the Japanese interregnum. His second decade marked his life-changing stint at the famous Sultan Idris Training College in Malaysia, a hotbed of Malay nationalism where Malay teachers throughout Malaya, Borneo and Singapore were trained; his third decade saw his active involvement in ASAS ’50 (The Singapore’s Writers’ Movement established in 1950) and the impending independence of Malaya; his fourth decade saw the push for Malay language as a medium of education; and his fifth decade saw the institutionalisation of two Malay-Muslim bodies in Singapore, namely MUIS and MENDAKI, to oversee the educational and religious welfare of the community.

By the time he turned 60, Suratman had witnessed several turbulent regional and international events. In his 70s, he became contemplative, reflecting on and searching for the meaning of life and his service to the Creator.

Today at the age of 83, Suratman is still writing and compiling his works to make them available to contemporary audiences. He continues to teach, and delivers seminars locally and regionally. His research on Malay literature reflects the breadth of his thought. While he is skilled at narrating short stories, he is no less excellent in crafting essays or literary history, projecting its trajectories and nuances over time.22 He has also edited Singapore-Malay literary works for Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka (DBP), putting Singapore-Malay works on the map of Malaysian, Bruneian and Indonesian literary scholarship.

The Significance of Marking Social Memories

Suratman has meticulously documented what he has experienced, expressing his perspectives, lamentations and even joy. He is very conscious of how history has impacted his people, namely their plight of displacement and neglect. He actively engages with the issues of his community and nation, convinced that writers are the “eyes of the society.” Suratman is thus a poet of conscience, cognizant of societal issues, as well as the flag bearer of morality, defender of human dignity and preserver of group identity.

Singapore has experienced vast changes in a short period of time, with many of its common spaces, institutions and practices disappearing from the landscape; even our memories of yesteryear are fading. Herein lies the role of the writer who is seen as the conscience of his society and the purveyor of humanity. As a writer Suratman’s work is firmly didactic, imparting a strong moral message; he is more concerned with the moral and intellectual presence of literature, not so much its ornaments or finesse.

The sense of loss that Suratman writes about is not just the loss that he experienced on a personal level, but one that can also be related to the loss of his community. His own loss makes him consistently relate his thoughts and sentiments. As evidenced by his voluminous legacy, he is writer, narrator and commentator of social memories that are dissipating in our midst. Indeed the stamina for remembrance is often circumscribed in an era that celebrates newness. We must keep in mind that our progress and development is rendered meaningless if we are bereft of appreciating the past. To build a future, moulding it to our needs and character requires a sense of place and being. Suratman’s memory is a search in as much as it is a hope, but as a poet his scepticism warrants us to consider our destinies seriously:

Singapuraku / aku mengerti sekali / di sini tempatku / tapi aku tidak tahu bila / aku akan menemui segala kehilanganku? 23

My Singapore / I truly understand / here is my home / yet I do not know when / I will recover what I have lost.

Dr Azhar Ibrahim is a Visiting Fellow at the Department of Malay Studies, National University of Singapore. He teaches classical and modern Malay-Indonesian literature.

REFERENCES

Ngugi, w.T. (2009). Something torn and new (p. 114). New York: BasicCivitas Books. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Siti Zainon Ismail. (2001). Potret isteri yang hilang (pp. 322–333). In Johar Buang (Ed.), 70 tahun Suratman Markasan. Singapore: Toko Buku Hj Hashim. (Call no.: Malay RSING 899.28024 TUJ)

Suratman Markasan. (2013). Balada seorang lelaki di depan patung Raffles (h.45). In Kembali ke akar Melayu kembali ke akar Islam. Jilid 1, Kumpulan puisi 1954 – 2011. Singapore: Darul Andalus. (Call no.: Malay RSING 899.281 SUR)

Suratman Markasan. (2013). Cerita peribumi Singapura (h. 57). In Kembali ke akar Melayu kembali ke akar Islam. Jilid 1, Kumpulan puisi 1954 – 2011. Singapore: Darul Andalus. (Call no.: Malay RSING 899.281 SUR)

Suratman Markasan. (2013). Dalam perjalanan masa (h. 257). In Kembali ke akar Melayu kembali ke akar Islam. Jilid 1, Kumpulan puisi 1954 – 2011. Singapore: Darul Andalus. (Call no.: Malay RSING 899.281 SUR)

Suratman Markasan. (2013). Di balik bayang Tun Seri Lanang (h. 412). Kembali ke akar Melayu kembali ke akar Islam. Jilid 1, Kumpulan puisi 1954 – 2011. Singapore: Darul Andalus. (Call no.: Malay RSING 899.281 SUR)

Suratman Markasan. (2013). Jalan permulaan {Buat Suri, Lita & Tauliq) – The Journey begins (h.10, 12). In Kembali ke akar Melayu kembali ke akar Islam. Jilid 1, Kumpulan puisi 1954 – 2011. Singapore: Darul Andalus. (Call no.: Malay RSING 899.281 SUR)

Suratman Markasan. (1978). Kesusasteraan Melayu Singapura Dulu, sekarang dan masa depan, dalam Persidangan Penulis ASEAN (h. 299–324). Kuala Lumpur: DBP. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Suratman Markasan. (2013). Masih adakah melayu di sini? (h. 458). In Kembali ke akar Melayu kembali ke akar Islam. Jilid 1, Kumpulan puisi 1954 – 2011. Singapore: Darul Andalus. (Call no.: Malay RSING 899.281 SUR)

Suratman Markasan. (2013). Mencari melayu yang melayu (h. 454). In Kembali ke akar Melayu kembali ke akar Islam. Jilid 1, Kumpulan puisi 1954 – 2011. Singapore: Darul Andalus. (Call no.: Malay RSING 899.281 SUR)

Suratman Markasan. (2005). Bangsa Melayu Singapura dalam transformasi budayanya. Singapore: Anuar Othman & Associates. (Call no.: Malay RSING 305.8992805957 SUR)

Suratman Markasan. (2013). Kembali ke akar Melayu kembali ke akar Islam. Jilid 1, Kumpulan puisi 1954 – 2011. Singapura: Darus Andalus. (Call no.: Malay RSING 899.281 SUR)

Suratman Markasan. (1987). Tiga warna bertemu: Antologi puisi penulis-penulis Singapura. Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka. (Call no.: Malay RSING S899.230081305 TIG)

NOTES

-

Other awards include: Montblanc-NUC Centre for the Arts Literary Award (1997), Anugerah Pujangga from UPSI in 2003. Singapore Malay Language Council accorded to him the highest literary award of Tun Seri Lanang in 1999. ↩

-

Suratman Markasan. (2013). Kembali ke akar Melayu kembali ke akar Islam. Jilid 1, Kumpulan puisi 1954 – 2011. Singapura: Darus Andalus. (Call no.: Malay RSING 899.281 SUR) ↩

-

Siti Zainon Ismail. (2001). Potret isteri yang hilang (pp. 322–333). In Johar Buang (Ed.), 70 tahun Suratman Markasan. Singapore: Toko Buku Hj Hashim. (Call no.: Malay RSING 899.28024 TUJ) ↩

-

His two novels, Suratman Markasan. (1998). Penghulu yang hilang segala-galanya. Shah Alam: Penerbit Fajar Bakti. (Call no.: Malay RSING 899.283 SUR) has been translated into English [Solehah Ishak (Translater). (2012). Penghulu. Singapore: Epigram Books. (Call no.: RSING 899.283 SUR]. His first novel Suratman Markasan. (1962). Ta’ada jalan keluar. Singapura: Marican. (Call no.: Malay RSING S899.2305 SUR) has been translated into English as [Mohd. Saleh Sani. (Translater). (1980). Conflict. Singapore: Marican. (Call no.: RSING S899.2305 SUR)] ↩

-

Suratman Markasan. (1987). Tiga warna bertemu: Antologi puisi penulis-penulis Singapura. Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka. (Call no.: Malay RSING S899.230081305 TIG) ↩

-

Ngugi’s reflection on this point is relevant in many developing societies: Writers, artists, musicians, intellectuals, and workers in ideas are the keepers of memory of a community. What fate awaits a community when its keepers or memory have been subjected to the West’s linguistics means of production and storage of memory…we have languages, but our keepers of memory feel that they cannot store knowledge, emotions, and intellectual in [their] languages. Ngugi, w.T. (2009). Something torn and new (p. 114). New York: BasicCivitas Books. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Read Suratman Markasan. (2005). Bangsa Melayu Singapura dalam transformasi budayanya. Singapore: Anuar Othman & Associates. (Call no.: Malay RSING 305.8992805957 SUR) ↩

-

Suratman Markasan. (2013). Di balik bayang Tun Seri Lanang (h. 412). In Kembali ke akar Melayu kembali ke akar Islam. Jilid 1, Kumpulan puisi 1954 – 2011. Singapore: Darul Andalus. (Call no.: Malay RSING 899.281 SUR) ↩

-

Suratman Markasan. (2013). Masih adakah melayu di sini? (h. 458). In Kembali ke akar Melayu kembali ke akar Islam. Jilid 1, Kumpulan puisi 1954 – 2011. Singapore: Darul Andalus. (Call no.: Malay RSING 899.281 SUR) ↩

-

Suratman Markasan. (2013). Jalan permulaan {Buat Suri, Lita & Tauliq) – The Journey begins (h.10). In Kembali ke akar Melayu kembali ke akar Islam. Jilid 1, Kumpulan puisi 1954 – 2011. Singapore: Darul Andalus. (Call no.: Malay RSING 899.281 SUR) ↩

-

Suratman Markasan. (2013). Dalam perjalanan masa (h. 257). In Kembali ke akar Melayu kembali ke akar Islam. Jilid 1, Kumpulan puisi 1954 – 2011. Singapore: Darul Andalus. (Call no.: Malay RSING 899.281 SUR) ↩

-

Suratman Markasan. (2013). Balada seorang lelaki di depan patung Raffles (h.45). In Kembali ke akar Melayu kembali ke akar Islam. Jilid 1, Kumpulan puisi 1954 – 2011. Singapore: Darul Andalus. (Call no.: Malay RSING 899.281 SUR) ↩

-

Suratman Markasan. (2013). Mencari melayu yang melayu (h. 454). In Kembali ke akar Melayu kembali ke akar Islam. Jilid 1, Kumpulan puisi 1954 – 2011. Singapore: Darul Andalus. (Call no.: Malay RSING 899.281 SUR) ↩

-

Suratman Markasan. (2013). Cerita peribumi Singapura (h. 57). In Kembali ke akar Melayu kembali ke akar Islam. Jilid 1, Kumpulan puisi 1954 – 2011. Singapore: Darul Andalus. (Call no.: Malay RSING 899.281 SUR) ↩

-

For instance read, Suratman Markasan. (1978). Kesusasteraan Melayu Singapura Dulu, sekarang dan masa depan, dalam Persidangan Penulis ASEAN (h. 299–324). Kuala Lumpur: DBP. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Suratman, Jalan permulaan (Buar Suri, Lita & Taufiq) – The Journey begins, 2013, h. 12. ↩