Chinese Clan Associations in Singapore: Then and Now

Chinese clan associations in Singapore date back to the time of Stamford Raffles. Lee Meiyu shows us how the functions of clan associations have changed over the years according to the needs of the local Chinese community as well as changes in state policy.

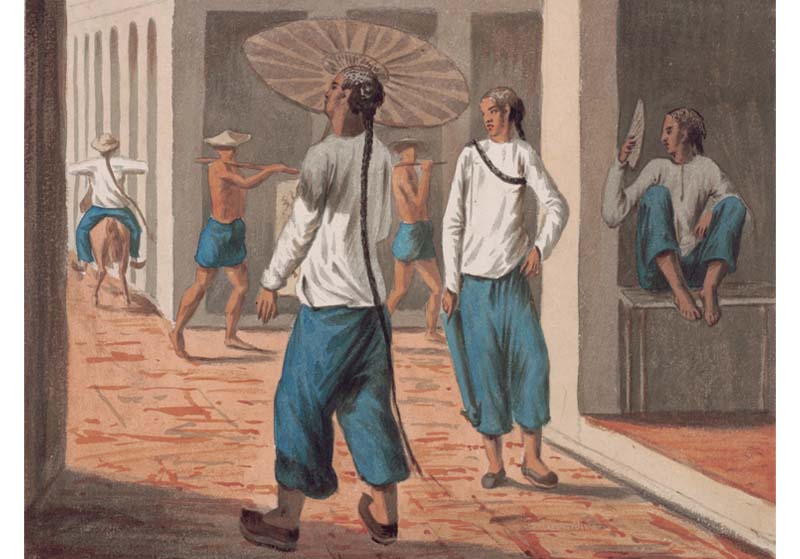

Chinese migrants in Singapore as depicted by E. Schlitter in 1858. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

Chinese migrants in Singapore as depicted by E. Schlitter in 1858. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.Chinese clan associations have had a long and chequered history in Singapore. The first ever clan association established on the island was said to be Cho Kah Koon (Cao Jia Guan曹家馆), started by an immigrant called Chow Ah Chey (Cao Yazhi曹亚志) in 1819. Chow was a carpenter on board the same ship as Stamford Raffles, founder of modern Singapore, when he spotted Temasek (old Singapore) for the first time. Chow volunteered to go on shore to explore the island and in reward of his bravery, Raffles granted him a piece of land upon which the first Chinese clan association was built.

The building served as a rest stop for Chow’s kin, the Chow clansmen from Taishan district in Guangdong Province (Guangdong Taishan Ji Cao Shi 广东台山籍曹氏). In 1849, the East India Company officially granted the land it occupied at No. 1 Lavender Street to the association.1 Today, the association is known as Sing Chow Chiu Kwok Thong Cho Kah Koon (Xingzhou Qiaoguo Tang Cao Jia Guan 星洲谯国堂曹家馆) and has since relocated to No. 107-B Joo Chiat Road.2

Although historians have questioned the accuracy of the origins of Cho Kah Koon,3 it nevertheless reflects the raison d’être for establishing clan associations in Singapore: to offer a place of safety and help to fellow kin from China. From the 19th to early 20th century, thousands of immigrants, including the Chinese, came to Singapore in search of job and trading opportunities. The colonial government welcomed these much needed traders and menial labourers, adopting the “divide and rule” method of governance. However, this hands-off approach did not help create a cohesive society and discouraged integration, and the building of a much needed social system was left to each individual ethnic community.4

The Chinese community responded by transplanting their revered centuries-old social structures, in the form of clan associations, into Singapore. To the Chinese, their elaborate family and clan systems had always been the biological, economic and social units that formed the basis of traditional society. These structures also provided social support as family or clan members had an obligation to help one another. In a fledgling Singapore where integration was not encouraged and a state-led support system was absent, the Chinese community turned to their clan organisations for leadership and assistance.

Rise of Religious Associations and Secret Societies (1819–1889)

Interestingly, clan associations were not the default go-to for the Chinese in the early years: instead the newly arrived migrants turned to religious associations and secret societies. The Chinese community at the time comprised small-time businessmen, craftsmen and labourers who had come to Singapore alone, hence there were not enough clan members to form an association. However, religious rites and processions were often organised for the migrants who prayed for protection and asked for blessings from the deities. Such activities became a central part of an Overseas Chinese’s social life and eventually gave rise to religious associations.

Temples soon became key organisations providing the Chinese with much needed guidance and entertainment in a society where back-breaking work and loneliness were the order of the day. These temple associations also offered help in settling burial matters, finding jobs and served as meeting places. Their board members were usually influential leaders in the Chinese community who presented the concerns of their members to the colonial government or settled disputes between members and associations.5

While religious associations flourished due to the Chinese community’s need for spiritual fulfillment, secret societies grew out of the colonial government’s need to control and organise the Chinese community without hampering the economic progress of Singapore. The British were more preoccupied with economic activities and turning Singapore into a successful entrepôt in the early years, leaving them with scant time and resources to develop a state governance system. The only governance systems available were the existing Kapitan China and Kangchu systems, which had been adopted from the Malay rulers or earlier colonial powers in the region.

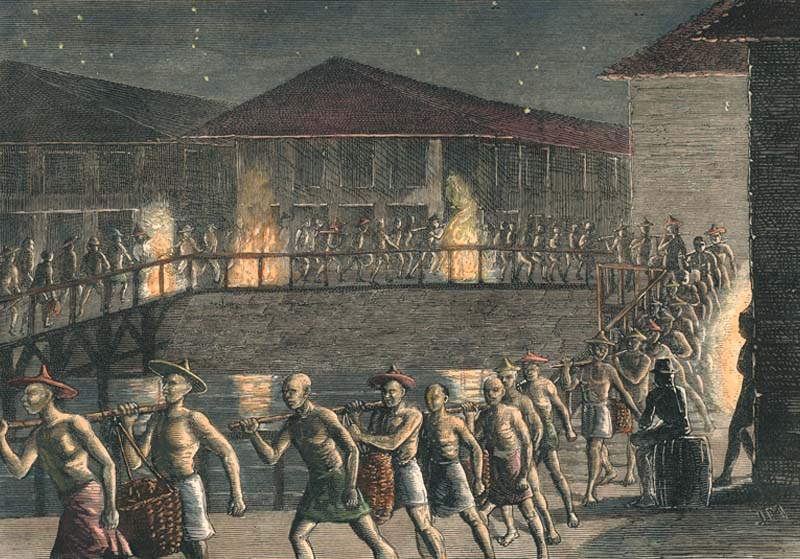

Many Chinese migrants came to Singapore to seek work to support their families in China. Artist unknown, wood engraving, published in The Graphic, 4 November 1876. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

Many Chinese migrants came to Singapore to seek work to support their families in China. Artist unknown, wood engraving, published in The Graphic, 4 November 1876. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.  Tattoo on a secret society member. Secret societies have existed in Singapore since the 1800s. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Tattoo on a secret society member. Secret societies have existed in Singapore since the 1800s. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Both systems involved appointing an influential Chinese to oversee all issues related to the Chinese community, including maintaining law and order in the Chinese quarter. This person, known as the Kapitan or Kangchu, served as the liaison between the colonial government and the Chinese, and enjoyed privileges such as market monopoly and tax collection rights. Eventually, the Kapitan and Kangchu became a very rich and powerful group. As leaders of the Chinese community, the Kapitan and Kangchu played an active role in both the religious associations and secret societies, since these were the two most powerful Chinese organisations at the time. Many of their members might also have held memberships in both organisations.6

Rise of Clan Associations (1890–1947) 7

Secret societies were at their peak in the late 19th century. The Chinese who came to Singapore were from different parts of China and spoke dialects that were unintelligible to each other, making it impossible to communicate outside their own dialect groups. This communication barrier facilitated the formation of secret societies that were divided by dialect. Over time, the secret societies grew powerful and started to actively protect their own group interests at the expense of others. They established their own territories and other dialect groups were not allowed to cross the invisible boundaries; if they did, fights would break out.

The increasing conflict and fights between dialect groups soon drew the attention of the colonial government as great financial losses were incurred in terms of property damage and social disruption. The colonial government started clamping down on secret societies with a series of legislations starting from 1869.8 This included the 1889 Society Ordinance which effectively outlawed secret societies by requiring all organisations to register themselves with the colonial government before they could be recognised as legal bodies.9

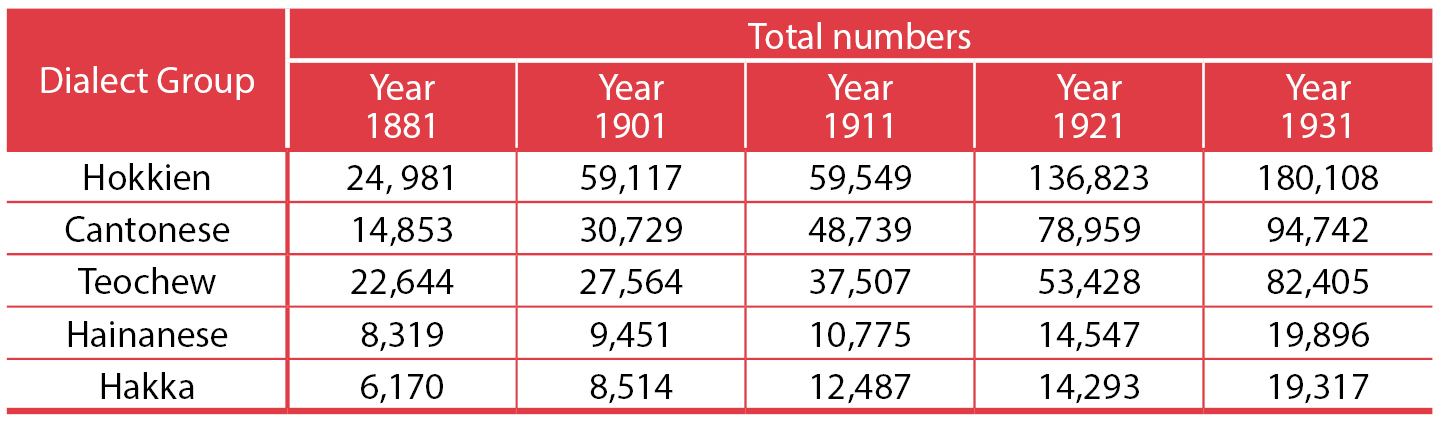

Table 1: Distribution of Chinese population by the five major dialect groups in Singapore.10

Table 1: Distribution of Chinese population by the five major dialect groups in Singapore.10

With intervention by the colonial government, the control of secret societies over the Chinese community started to weaken.11 A leadership void within the Chinese community opened, which the clan associations gladly filled. In reality, clan associations had always been around, co-existing with secret societies and religious associations, but had been relegated to the periphery of the Chinese community because of their small membership base.

However, as more Chinese migrants arrived, clan associations grew bigger and stronger, particularly when kinship-sponsored schemes brought more people of the same lineage in. Later, when clan associations were recognised as legal bodies by the colonial government, they became more attractive than secret societies.12

There were two types of clan associations: (a) locality-based, where members came from the same geographical area, but might not be blood related; and (b) lineage-based, where members had the same surname but were not necessarily from the same geographical area.13 Both associations generally provided services related to welfare and religious activities such as:

(a) worship of Protector Gods;

(b) ancestral worship;14

(c) observance of seasonal festivals,

(d) helping destitute members by recommending jobs, financing education or burial matters and others; and

(e) arbitration of disputes.15

Looking at the functions that early clan associations fulfilled, it is clear that their primary aim was to help newly arrived kin to settle down in Singapore. This became especially important when migrants arrived alone and clan associations were the only places they could turn to for help. It became vital to join clan associations for one’s success, or even survival.

In the early 1900s, clan associations became more directly involved with the political situation in China. The Chinese revolutionaries who came to Southeast Asia seeking financial support from the Overseas Chinese for their activities in China found favour with the Chinese community in Singapore. Most Overseas Chinese viewed Singapore as a temporary stop for work and trade, hoping to return to China one day with their riches. Their emotional and political allegiance was to China where their families were. Historical events such as the fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1911 and the Sino-Japanese War in the 1930s led to the realisation that China had to become stronger in order to protect her own interests. To this end, the Overseas Chinese were willing to contribute money to the motherland or even volunteer to fight in her wars.

Fundraising and mobilisation of support required organisation and by this time, there were already several established clan associations led by respected Chinese leaders, many of whom were successful businessmen in the Chinese community.16 These leaders were politically well connected and their wealth and networks made them the best people to organise such activities.

Members of Kiung Chow Hwee Kuan helping out with registration of Singapore citizenship at the Chinese Chamber of Commerce, one of six registration centres in 1957. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Members of Kiung Chow Hwee Kuan helping out with registration of Singapore citizenship at the Chinese Chamber of Commerce, one of six registration centres in 1957. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Decline of Clan Associations (1942–1985)

During the Japanese Occupation (1942–1945) of Singapore, the active involvement of clan associations’ leaders and their members in anti-Japanese activities made them targets. Many of these leaders and members either fled Singapore or risked being captured and executed by the Japanese. Clan associations went into hibernation as their leaders and members disappeared and the Chinese community lived in fear of their new Japanese masters.17

After the war, the British continued their governance amid a growing sense of nationalism among the masses. Clan activities were revived, especially the re-establishment of Chinese vernacular schools that were disrupted during the war.18 By the 1950s, the push for self-governance and rise of young local politicians eventually culminated in the independence of Singapore in 1965.

In its first 10 years of Independence, the Singapore government faced an uphill task in unifying a population of migrants comprising different ethnicities and cultural backgrounds. For the Chinese community, this shift in political allegiance from China to Singapore started when the Chinese government outlawed dual citizenship in 1955, forcing many local Chinese to take up Singapore citizenship in order to stay on. As nation-building efforts progressed, state policies and centralised state systems catering for welfare, education and housing were created. These policies and systems in turn replaced the functions traditionally offered by clan associations to the Chinese community during the colonial days.19

The 1984 seminar which re-examined the roles of Chinese clan associations in modern-day Singapore. It led to the formation of the umbrella body, Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations, in 1986. Courtesy of Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations.

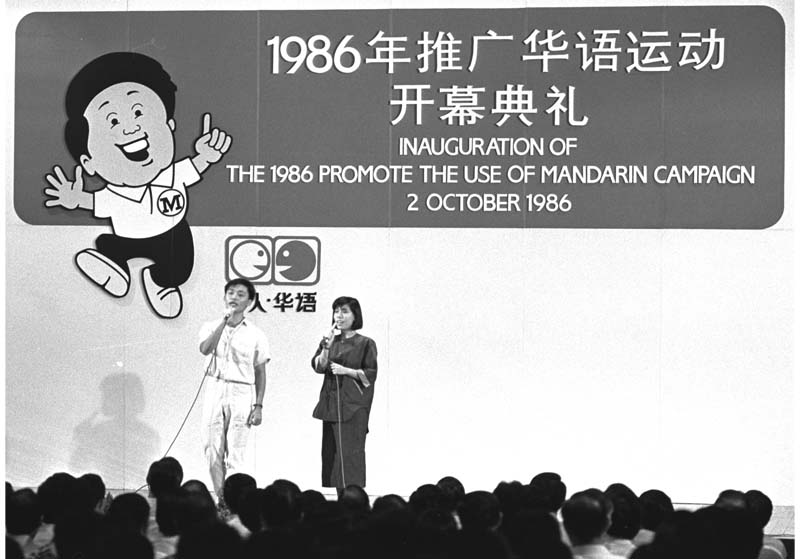

The 1984 seminar which re-examined the roles of Chinese clan associations in modern-day Singapore. It led to the formation of the umbrella body, Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations, in 1986. Courtesy of Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations. Launch of the campaign to use Mandarin in 1986. The use of dialects began to decline as the population was encouraged to speak more Mandarin. MITA collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Launch of the campaign to use Mandarin in 1986. The use of dialects began to decline as the population was encouraged to speak more Mandarin. MITA collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.In post-Independent Singapore, the character of the Chinese population went through a process of change. To create a common identity, the Singapore government adopted the concept of a multi-racial society. The population of Singapore was neatly divided into four ethnic categories: Chinese, Malays, Indians, and Others (CMIO). While this made it easier for the government to formulate and push out policies at the national level, it also began to erode Chinese dialect identities, which had been the fundamental basis of all clan associations.

The government also started taking steps to remove elements of society that were viewed as engendering ethnic chauvinism. From the 1970s to 80s, a series of campaigns and policies – such as the Speak Mandarin Campaign, banning the use of dialects in mass media and the shutting down of vernacular Chinese schools created younger generations of Chinese Singaporeans who communicated ably in Mandarin but could barely speak their own dialects. The dialect identities of the Chinese community, which had once created social strife and division in the colonial years, were slowly eroded. In addition, Singapore-born Chinese felt little attachment to China, and thus had little use for the services and kinship previously provided by the clan associations. The clan associations suddenly found themselves struggling with dwindling and ageing memberships, branded by the younger generations as “old-fashioned” and “traditional”.20

Voices pushing for transformation began to surface in the 1970s. On 2 December 1984, a seminar focusing on the new roles of clan associations in the modern era was held. Attended by 185 clan associations, the opening speech given by then Second Deputy Prime Minister Ong Teng Cheong outlined five directions of future development for the associations:

(a) open their membership to all Singaporeans, irrespective of race and dialect;

(b) groom a younger leadership for renewal;

(c) intensify cultural and educational activities such as organising large-scale cultural and recreational activities to promote arts and festivals, publishing books and magazines, and collecting, preserving and exhibiting cultural heritage of associations;

(d) set up homes for the aged, crèches, and care-centres for different age-groups; and

(e) co-ordinate with other community organisations for community development.21

The seminar concluded that regardless how the political environment might have changed, it was still important to retain one’s cultural roots. In an increasingly Westernised Singapore society, the task of preserving and promoting Chinese culture and language took on an urgent note as younger Singaporeans were becoming increasingly detached from their own heritage. From the 1980s onwards, both the government and clan associations agreed that the associations should take an active role in promoting Chinese culture to all.22

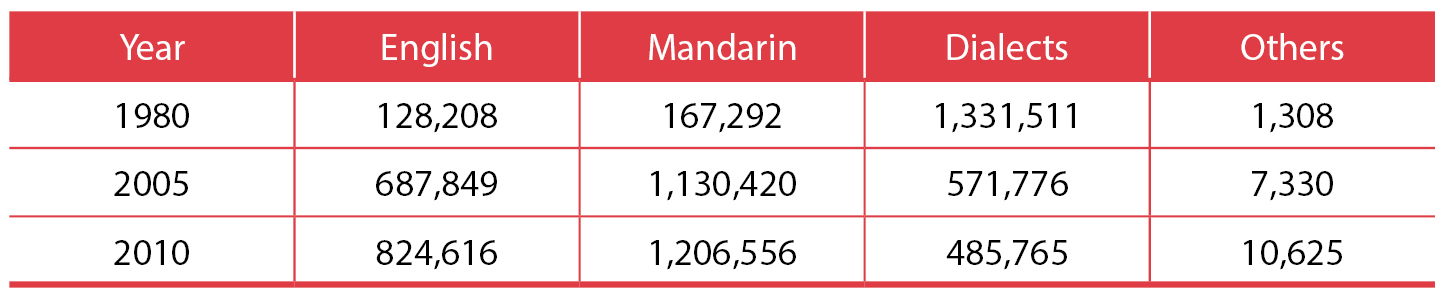

Table 2: Language most frequently spoken at home by resident Chinese population aged five years and over.23

Table 2: Language most frequently spoken at home by resident Chinese population aged five years and over.23

Revitalisation of Clan Associations (1986–2000s)

On 27 January 1986, the Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations (SFCCA),24 an umbrella authority for all Chinese clan associations, was established. This bold move was to unite the various clan associations under one common purpose and direction: that of promoting Chinese culture and language to all, regardless of their dialect, ethnicity and nationality. Major cultural events (for instance River Hongbao, which celebrates Chinese New Year), exhibitions and publications related to Chinese culture and language are held or produced with support from the Singapore government. The SFCCA also publishes a magazine, Yuan (《源》), that serves as the publicity channel introducing members’ activities and articles about Chinese culture.25

Modern-day Chinese clan associations organise events and activities that promote awareness and understanding of the Chinese culture in an effort to reach out to younger Chinese and remind them of their identity. Image by Hung Chung Chih.

Modern-day Chinese clan associations organise events and activities that promote awareness and understanding of the Chinese culture in an effort to reach out to younger Chinese and remind them of their identity. Image by Hung Chung Chih.Existing clan associations under the leadership of the SFCCA generally provide the following:

(a) social welfare such as scholarships or funds for the needy;

(b) ancestral worship services;

(c) youth activity groups to attract younger generations;

(d) Chinese cultural centres where classes and seminars are held to promote Chinese culture;

(e) publishing or sponsoring publications and events related to Chinese culture; and

(f) (for the bigger clan associations) working closely with similar organisations in other countries to organise international conferences and overseas social or business trips for their members.26

These services reflect the strong intention of SFCCA and its members to reinvent themselves to suit the needs of the modern Singaporean Chinese. In addition, the clans are also aware of the importance of attracting new migrants, given the renewed wave of Chinese migrations from China under Singapore’s open-door population policy.

The efforts of the SFCCA and its members have paid off as there has been an increase in media publicity and in the scale and number of activities organised for members. Some associations have also been successful in attracting younger members.

What is interesting, however, is that in the Singapore context, this renewal process has been achieved at the expense of blurring dialect identities, while on the international level, proponents of Chinese race and culture continue to tap on their strong dialect networks to act as bridges between Singaporeans and other Chinese societies. The identity dilemma of Chinese clan associations in Singapore will, perhaps, always exist.

The role of Chinese clan associations in Singapore, from the colonial years to modern times, have been strongly influenced, or even dictated at times, by the policies of the colonial and Singapore governments. The absence and presence of state policies influenced not only the growth and direction of the clan associations but also the composition and character of the Chinese community in Singapore, the main consumers of the services provided by the associations. Clan associations have been able to survive due to their ability to adapt to the changing needs of the Chinese community in Singapore as well as that of the government’s. The appearance of new associations formed by the latest wave of Chinese migrants adds another layer of diversity and complexity to Chinese organisations in Singapore. It remains to be seen how these old and new organisations will work together for the future development of the country.27

The Fujian Association at Telok Ayer Street still stands today, looking little different from when it was first built in 1913.

The Fujian Association at Telok Ayer Street still stands today, looking little different from when it was first built in 1913.

Lee Meiyu is a Librarian with the National Library of Singapore. She has co-written publications such as Money by Mail to China: Dreams and Struggles of Early Migrants and Roots: Tracing Family Histories – A Resource Guide.

REFERENCES

Cheng, K.L. (1990). Reflections on the changing roles of Chinese clan associations in Singapore. Asian Culture, 14, 57–71.

崔贵强 [Cui, G]. (1994). 新加坡华人 : 从开埠到建国=The Chinese in Singapore: Past and present. Singapore: Singapore Federation of Clan Associations. (Call no.: RSING 959.57004951 CGQ)

Kuah-Pearce, K.E., & Hu-Dehart, E. (Eds.). (2006). Voluntary organizations in the Chinese Diaspora. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. (Call no.: RSING 366.0089951 VOL)

Lee, E. (1991). The British as rulers governing multiracial Singapore 1867–1914. Singapore: Singapore University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57022 LEE)

Lin, Y. (2010). 回顾25: 宗乡总会二十五周年文辑, 1985-2010 [Looking back 25 years: Compilation of papers for the 25th anniversary of the Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations]. Singapore: Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations. (Call no.: Chinese RSING 369.25957 HGE)

Liu, H., & Wong, S.K. (2004). Singapore Chinese society in transitions: Business, politics, and socio-economic change, 1945–1965. New York: Peter Lang Pub. (Call no.: RSING 959.5704 LIU)

潘明智 [Pan, M.]. (Ed.). (1996). 华人社会与宗乡会馆 [The Chinese society and clan associations]. Singapore: Ling zi da zhong chuan bo zhong xin. (Call no.: RCO 909.04951 PBT)

星洲谯国堂曹家馆 [Sing Chow Chu Kwok Thong Cho Kah Koon]. (1985). 星洲谯国堂曹家馆一百六十五周年纪念特刊 = Sing chow chiu kwok thong cho kah koon 165th anniversary souvenir magazine 1984. Xin jia po: [Gai guan]. (Call no.: Chinese RSING 369.25957 SIN)

Singapore. Department of Statistics. (1981). Census of population 1980 Singapore. Release no. 8, languages spoken at home. Singapore: Department of Statistics. (Call no.: RSING 312.095957 CEN)

Singapore. Department of Statistics. (2011). Census of population 2010. Statistical release 1, Demographic characteristics, education, language and religion. Singapore: Department of Statistics, Ministry of Trade and Industry. (Call no.: RSING 304.6021095957 CEN)

Singapore. Department of Statistics. (2006). General household survey 2005: Socio-demographic and economic characteristics. Singapore: Department of Statistics. (Call no.: RSING 304.6095957 CEN)

Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations. (2005). 新加坡宗乡会馆史略 = History of Clan Associations in Singapore. (Vol. 2). 新加坡: 新加坡宗乡会馆联合总. (Call no.: Chinese RSING q369.25957 HIS)

Wu, H.Z. (1975). 新加坡华族会馆志 [Records of Chinese associations in Singapore] (Vol. 2). Singapore: South Seas Society. (Call no.: RCO 369.25957 WH)

Yen, C.H. (1995). Community and politics: The Chinese in colonial Singapore and Malaysia. Singapore: Times Academic Press. (Call no.: RSING 305.895105957 YEN)

庄国土 [Zhuang, G.], 清水纯 [Qing, S.]., & 潘宏立等著 [Pan, H.Z.D.]. (2010). 近30年东亚华人社团的新变化 = The changes of ethnic Chinese associations in East Asia since last 30 years. Xiamen: Xiamen University Press. (Call no.: Chinese RSING 305.895106 CHA)

Zhonghui 20 nian. [Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations: The twentieth year]. (2005). Singapore: Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Zhonghui san nian [Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations: The third year]. (1989). Singapore: Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations. (Not available in NLB holdings)

NOTES

-

Wu, H.Z. (1975). 新加坡华族会馆志 [Records of Chinese associations in Singapore] (Vol. 2; pp. 1–3). Singapore: South Seas Society. (Call no.: RCO 369.25957 WH) ↩

-

星洲谯国堂曹家馆 [Sing Chow Chu Kwok Thong Cho Kah Koon]. (1985). 星洲谯国堂曹家馆一百六十五周年纪念特刊 = Sing chow chiu kwok thong cho kah koon 165th anniversary souvenir magazine 1984 (p. 142). Xin jia po: [Gai guan]. (Call no.: Chinese RSING 369.25957 SIN) ↩

-

According to oral history, Cho Kah Koon was founded in 1819. However, there has been no documentation supporting this yet. There have also been debates that the real name of Chow Ah Chey could be Chow Ah Chi. For more details, refer to volume two of Xin jia po hua zu hui guan zhi [Records of Chinese associations in Singapore] by Wu Hua. ↩

-

庄国土 [Zhuang, G.], 清水纯 [Qing, S.]., & 潘宏立等著 [Pan, H.Z.D.]. (2010). 近30年东亚华人社团的新变化 = The changes of ethnic Chinese associations in East Asia since last 30 years (p. 32). Xiamen: Xiamen University Press. (Call no.: Chinese RSING 305.895106 CHA) ↩

-

潘明智 [Pan, M.]. (Ed.). (1996). 华人社会与宗乡会馆 [The Chinese society and clan associations] (pp. 419–420). Singapore: Ling zi da zhong chuan bo zhong xin. (Call no.: RCO 909.04951 PBT) ↩

-

The history of Chinese clan associations in Singapore have been divided into different eras by academics. For more details, refer to Pan, 1996, p. 466. ↩

-

Lee, E. (1991). The British as rulers governing multiracial Singapore 1867–1914 (pp. 140–150). Singapore: Singapore University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57022 LEE) ↩

-

Information adapted from Liu H., & Wong, S-K. (2004). Singapore Chinese society in transition: Business, politics, and social-economic change, 1945–1965. New York: Peter Lang Pub. (Call no.: RSING 959.5704 LIU) ↩

-

Apart from legislation, the colonial government also started gradually replacing existing governance systems with other forms if systems such as the appointment of W.A Pickering as the Protector of Chinese in 1877 and the establishment of the Chinese Advisory Board in 1889. ↩

-

Yen, C.H. (1995). Community and politics: The Chinese in colonial Singapore and Malaysia (p. 35). Singapore: Times Academic Press. (Call no.: RSING 305.895105957 YEN) ↩

-

In Singapore, ancestral worship activities organised by Chinese clan associations typically take place during Spring and Autumn, that is March to May and August to October. These rites are separately known as Spring Sacrifice [chunji (in Chinese)] and Autumn sacrifice [qiuji (in Chinese)]. ↩

-

Zhong hui 20 nian [Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Association” The twentieth year] (p. 12). (2005). Singapore: Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Kuah-Pearce, K.E., & Hu-Dehart, E. (Eds.). (2006). Voluntary organizations in the Chinese Diaspora (pp. 58–62). Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. (Call no.: RSING 366.0089951 VOL) ↩

-

Zhong 20 nian, 2005, p. 20. ↩

-

Information adapted from Singapore. Department of Statistics. (1981). Census of population 1980 Singapore. Release no. 8, languages spoken at home. Singapore: Department of Statistics. (Call no.: RSING 312.095957 CEN); Singapore. Department of Statistics. (2006). General household survey 2005: Socio-demographic and economic characteristics. Singapore: Department of Statistics. (Call no.: RSING 304.6095957 CEN); Singapore. Department of Statistics. (2011). Census of population 2010. Statistical release 1, Demographic characteristics, education, language and religion. Singapore: Department of Statistics, Ministry of Trade and Industry. (Call no.: RSING 304.6021095957 CEN) ↩

-

Before the formation of the Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations, the Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce acted as overall coordinator. ↩

-

Kuah-Pearce & Hu-Dehart, 2006, pp. 63–65. For more details on SFCCA’s activities, refer to their periodical Yuan or their anniversary publications. ↩

-

Kuah-Pearce & Hu-Dehart, 2006, pp. 67–71. ↩

-

To read more about the interactions between existing clan associations and the new associations set up by the latest wave of Chinese migrants, refer to 庄国土 [Zhuang, G.], 清水纯 [Qing, S.]., & 潘宏立等著 [Pan, H.Z.D.]. (2010). 近30年东亚华人社团的新变化 = The changes of ethnic Chinese associations in East Asia since last 30 years. Xiamen: Xiamen University Press. (Call no.: Chinese RSING 305.895106 CHA)1: Wu, H.Z. (1975). 新加坡华族会馆志 [Records of Chinese associations in Singapore] (Vol. 2; pp. 1–3). Singapore: South Seas Society. (Call no.: RCO 369.25957 WH) ↩