So, What is a Singaporean?

The National Day emblem outside City Hall at the 1963 National Day Rally held at the Padang. MITA collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The National Day emblem outside City Hall at the 1963 National Day Rally held at the Padang. MITA collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Let me begin with a paradox. I know that I am a Singaporean. But I do not know what a Singaporean is.

The best way to explain this paradox is to compare Singapore with other nations. There are three categories of nations with a clear sense of national identity. The first category is the old nation. Take France as an example. The French have zero doubts about their national identity. It is based on a common language, history, culture, relative ethnic homogeneity and deep attachment to key political concepts, like secularism. A Frenchman can recognise a fellow Frenchman in an instant. The bond is powerful and deep. This is equally true of other old nations, such as Japan and Korea, Russia and China, Spain and Sweden.

The second category is the new nation. The United States exemplifies this category best. It has no distinctive ethnic roots. It is an immigrant nation whose forefathers came from a variety of old nations. Yet somehow, within a generation (and often within less than a generation), their new citizens would lose their old national identities and be absorbed into the American melting pot.

Even though America declared its independence in 1776, it actually faced the danger of splitting into two nation states until the American Civil War of 1860–1865. Hence, the modern unified American nation is only about 150 years old.

Yet, there is absolutely no doubt that an American can recognise a fellow American when he walks the streets of Paris or Tokyo. When the fellow American opens his mouth, he knows that he is talking to a countryman.

A shared history, common historical myths, deep attachment to values like freedom and democracy are some of the elements that define the strong sense of American national identity.

It also helps to belong to the most successful nation in human history. A deep sense of national pride accompanies the sense of national identity.

Old Cultures, New Nations

The third category is the mixed category where national identity is a mixture of new and old. India and Indonesia, and Brazil and Nigeria exemplify this category. Both India and Indonesia have old cultures. But their sense of nationhood is relatively new. The boundaries that they have inherited are the accidental leftovers of European colonisation. For example, in the pre-colonial period, there were no nation states such as India and Pakistan or Indonesia and Malaysia. Their modern borders are a result of colonial divisions. Yet despite all this, both India and Indonesia have managed to develop strong and unique national identities.

Both Indians and Indonesians have no difficulty recruiting people to die for their countries. And they have done this despite the tremendous diversity of their societies. The story of Indian diversity is well known. In the case of Indonesia, it continues to be a source of daily discovery. The late Indonesian foreign minister Ali Alatas, a distinguished diplomat, told me how the Indonesian people were totally riveted by a series of TV programmes in the 1990s which showcased how children worked, studied and played all over the archipelago. Many Indonesians discovered this diversity for the first time.

Poor But Happy Community

Singapore does not belong to any of these three categories. Virtually everyone knows that Singapore is an accidental nation. Yet few seem to be conscious of how difficult it is to create a sense of national identity out of an accidental nation.

Take my personal case as an example. Most children get their sense of national identity from their mother’s milk. I did too.

As my mother had a close shave leaving Pakistan in 1947, she instilled a deep sense of Hindu nationalism in me. I learnt Hindi and Sindhi and read about Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru.

But it did not last. The realities of daily living in Singapore defined our identity.

Fortunately, I grew up in a relatively poor neighbourhood in Onan Road. Because we lived in one-bedroom houses – we actually lived in each other’s houses and not only in our own. My mother discovered that she had left her Muslim neighbours in Pakistan to develop very deep and close friendships with our Malay Muslim neighbours on both sides of our house.

We lived together almost as one family. Just beyond them were two Chinese families. One was Peranakan and the other was Mandarin-speaking. Three doors away was a Eurasian family.

Hence, in the space of seven or eight houses, we could see almost the full spectrum of Singapore’s ethnic composition living cheek by jowl with each other.

And we lived with deep ethnic harmony. At the height of the racial riots in 1964, even though one of my Malay neighbours returned home badly bruised and bloodied after being beaten by a Chinese mob, the ethnic harmony of our Onan Road community was never shaken. We saw ourselves as belonging to one community despite our ethnic and religious diversity.

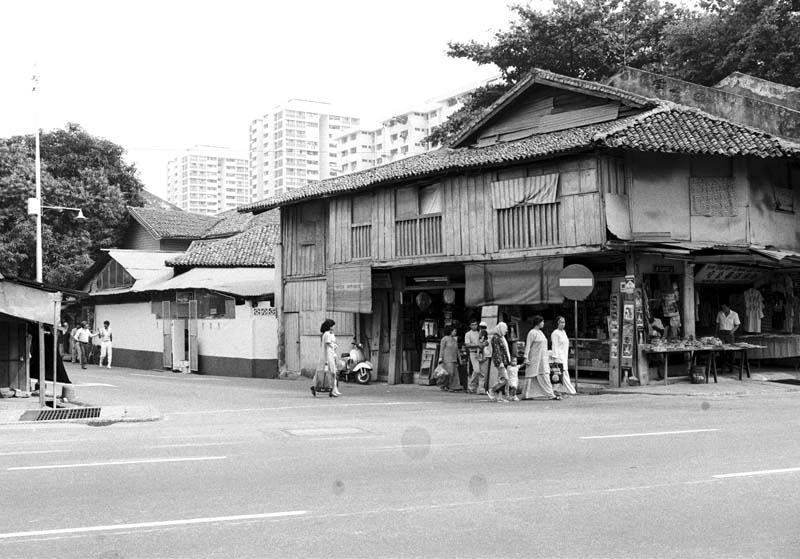

Row of shophouses along Onan Road in 1983. This multiracial neighbourhood in the East Coast was where the author spent his formative years. From the Lee Kip Lin Collection. All rights reserved. Lee Kip Lin and National Library Board, Singapore 2009.

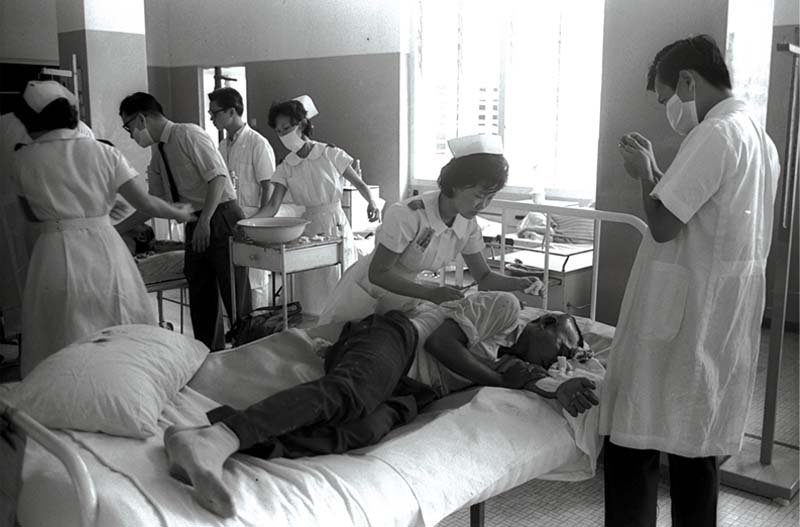

Row of shophouses along Onan Road in 1983. This multiracial neighbourhood in the East Coast was where the author spent his formative years. From the Lee Kip Lin Collection. All rights reserved. Lee Kip Lin and National Library Board, Singapore 2009. Medical staff at the General Hospital attending to racial riot victims in 1964. MITA collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Medical staff at the General Hospital attending to racial riot victims in 1964. MITA collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Natural, Artificial Harmony?

Singapore’s continued ethnic harmony, which has survived even bitter race riots, is clearly a key component of our sense of national identity. But one question remains unanswered: Is this ethnic harmony a result of natural evolution (as it was with our Onan Road community) or is it a result of harsh and unforgiving laws which allow no expression of ethnic prejudices? In short, is ethnic harmony in Singapore a natural or artificial development?

The answer to this question will determine Singapore’s future. If it is a natural development, Singapore will remain a strong and resilient society that will overcome divisive challenges.

If it is an artificial development, we will remain in a state of continuous fragility. As Singapore continues its mighty metamorphosis, we have to hope and pray that our ethnic harmony is a result of natural development.

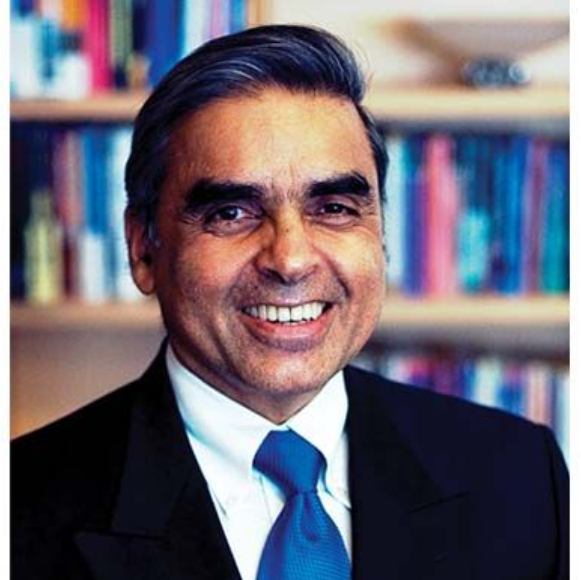

Kishore Mahbubani was with the Singapore Foreign Service for 33 years (1971–2004) and was Permanent Secretary at the Foreign Ministry from 1993 to 1998. Currently, he is the Dean and Professor in the Practice of Public Policy at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy of the National University of Singapore. His latest book, The Great Convergence: Asia, the West, and the Logic of One World, was selected by the Financial Times as one of the best books of 2013 and long listed for the 2014 Lionel Gelber Prize. Most recently, he was selected by Prospect magazine as one of the top 50 world thinkers for 2014.