Home and Away: Literary Reflections on Nation and Identity

Michelle Heng meanders through Singapore’s post-Independence literary landscape and discovers diasporic works that display a quiet strength even as they explore refreshingly dissonant views on nation and one’s identity.

Singapore’s stunning skyline is a much-photographed sight. While the soaring steel-and-glass buildings are a powerful symbol of the city’s triumphant nation-building efforts, it is also a reminder of lost heritage and lives that have been displaced in the unrelenting pursuit of commercial success. As the poet Goh Poh Seng so succinctly described in his poem “Singapore”, it is a “city that does not even permit the memory of the sky”.

Singapore’s stunning skyline is a much-photographed sight. While the soaring steel-and-glass buildings are a powerful symbol of the city’s triumphant nation-building efforts, it is also a reminder of lost heritage and lives that have been displaced in the unrelenting pursuit of commercial success. As the poet Goh Poh Seng so succinctly described in his poem “Singapore”, it is a “city that does not even permit the memory of the sky”.In the aftermath of a devastating World War II, budding writers in Malaya honed their craft by publishing works that appeared in varsity literature, empowered as they were by a fiery desire to forge a common literary voice in English. With the establishment of the University of Malaya in 1949, the students were likely moved to wield their pens by the 1948 Carr-Saunders Commission Report which articulated that “The University of Malaya will provide for the first time a common centre where varieties of race, religion and economic interest could mingle in a joint endeavour…For a University of Malaya must inevitably realise that it is a university for Malaya.”

Eager to partake in the moulding of a bright future in what was to become the new Malayan nation to-be, young student writers took on the mantle of establishing a Malayan literature for their countrymen who came from disparate communities that would, as part of a wide swathe of the Malayan cultural fabric, give Malayans a common national identity to aid their herculean endeavours in nation-building.1

Young and fledgling writers of the time such as Goh Sin Tub, Beda Lim, James Puthucheary, Lim Thean Soo, Hedwig Aroozoo, Wang Gungwu, James Loh and Edwin Thumboo published their works in the university’s main literary magazine, The New Cauldron, which was the successor to The Cauldron, an effort by the students of the former King Edward VII School of Medicine.2

The other reputable literary publications of this period included The Malayan Undergrad and Write from the late 1940s through to the 1950s, as well as magazines such as Focus and Monsoon in the 1960s. The first anthology of Malayan poetry, Litmus One (1958), and the first anthology of short stories, The Compact (1959), were also produced at this time.3 While the students remained hopeful of the prospects for a common Malayan literary voice in English, this proved elusive with the unfolding of major political developments in Malaya. Chief of this was Singapore’s acrimonious separation from Malaya in 1965, its northern neighbour promptly renaming itself Malaysia in the aftermath.

In the post-1965 era, Singapore set forth on a programme of industrialisation, boosted by the government’s ideology of economic pragmatism, legitimised by the fact that Singapore was previously thought to be untenable as an independent nation in terms of defence, economics and politics.4 Amid the trauma and troubling anxiety that arose from Singapore’s newly independent status as a city-state, there was an urgent need on the part of the government to cement the twin ideologies of nation-building and modernisation.

The main pursuits of nation-building included the advocacy of a multi-ethnic policy and the promotion of a bilingual proficiency with English as the lingua franca as well as a “mother tongue” of either Malay, Mandarin or Tamil. The push for modernisation called for a switch from traditional social practices to traits that were more compliant with the economic goals of industrialisation. Urban renewal projects eradicated agrarian practices to make way for industrial projects, housing development policies encouraged ethnic integration where previously close-knit ethnic communities had existed in enclaves, and mandatory military service was introduced for all males in an effort to forge a common national identity. 5

Public Verses, Personal Thoughts: Edwin Thumboo

Foremost among the architects of a nation-building literature was Edwin Thumboo, whose most significant work took root when he merged poetry and public concerns with the publication of Gods Can Die in 1977 and Ulysses by the Merlion in 1979. These two collections made clear his nationalist impulses and firmly established his belief that Singaporean writers should work to shape and expound on their nation’s identity.6

Said to command “a strong Virgilian proximity to power that no other Singaporean writer, past or present, has been known to enjoy”, Thumboo is recognised for the public role he has assumed through his verses that serve both as social commentary and national exhortation, his oeuvre par excellence being “Ulysses by the Merlion” – a paean to the Republic’s unexpected success as a well-run city-state following its enforced separation from Malaya.

Another example of a post-1956 poem by Thumboo that expounds the need for nation-building is seen in “Catering for the People” in which the poet declares, “There is little choice –/ We must make a people”.7 Indeed, he has publicly voiced his opinion of the writer’s responsibility thus:

I will always write about nation because it is part of my perception. / I will always see public issues. It was in the air I breathed; it was in / the sounds I heard. So I cannot help it.8

Thumboo actively sought to raise the literary consciousness and standards both at home and in Malaysia by putting together major anthologies. His first important collection was The Flowering Tree, published in 1970. Seven Poets appeared three years later and featured Wong Phui Nam, Goh Poh Seng, Wong May, Mohammad Haji Salleh, Lee Tzu Pheng, and Thumboo himself as strong regional voices. In 1979, Thumboo produced The Second Tongue, which carried his seminal introduction to a range of emerging poets in Singapore and Malaysia. The next decade saw Thumboo assume general editorship of two colossal multi-language anthologies: The Poetry of Singapore, published in 1985, and The Fiction of Singapore, published in 1990.

Thumboo was the first Singaporean to be conferred the prestigious S.E.A. Write Award in 1979 and Singapore’s Cultural Medallion for Literature in 1980. For his various contributions to nation-building, Thumboo was awarded a Bintang Bakti Masyarakat (Public Service Star) in 1981, with an additional Bar in 1991, in recognition of his role as a major influence on Singapore’s body of literature on nation-building.

Today, Thumboo remains highly prolific; one of his recent poems, “Bukit Panjang: Hill, Village, Town” (2012), is a sensitive portrayal of how Singapore’s evolving urban-renewed identity underpins the social, political and economic values that frame the Republic’s rapid growth during its post-Independence years. This four-part poem personifies the familiar landmark as a “Time-traveller; master of winds…” in its imposing geology, Bukit Panjang’s cultural significance as a village in the chaotic period during the Japanese Occupation before it finally settles comfortably into the role of an “established” new town as it gradually becomes “plump with amenities”. Set against the dramatic backdrop of the restive pre- and post-Colonial periods, and later during the “supercharged” nation-building years, the poem is one of Thumboo’s more recent efforts at blending his public voice and personal thoughts.

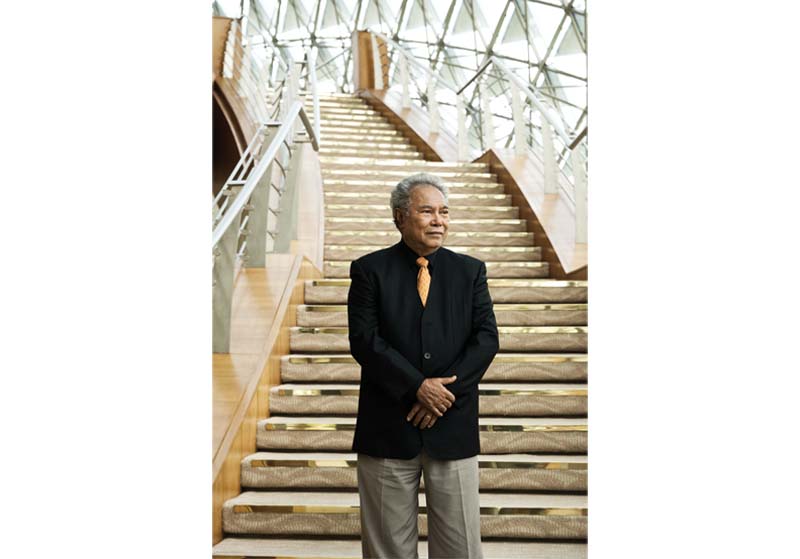

Edwin Thumboo is considered as one of Singapore’s foremost literary pioneers and continues to write today. Courtesy of Tribute.sg, an initiative by Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay and Edwin Nadason Thumboo.

Edwin Thumboo is considered as one of Singapore’s foremost literary pioneers and continues to write today. Courtesy of Tribute.sg, an initiative by Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay and Edwin Nadason Thumboo.Private Verses, Public Thought: Goh Poh Seng

It is here that another literary pioneer in Singapore must be given equal mention for his significant role as poet-playwright-novelist and as a tireless advocate of the nascent arts scene during Singapore’s nation-building years. Offering an interesting counterpoint to Thumboo’s purpose-filled poetry of a newly independent and industrious nation, the late Goh Poh Seng was one of the first Singapore writers who attempted to define post-Independence Singapore literature.

His first novel, If We Dream Too Long (1972), is widely recognised as the first true Singaporean novel. It was awarded the National Book Development Council of Singapore Book Prize in 1976 and has been translated into Russian, Tagalog and Japanese. In the novel, Goh explores the theme of searching for self and meaning against the dreary backdrop of rapid urbanisation and an increasingly materialistic society set in 1960s Singapore.

As the eldest son in a lower-middle class family, the protagonist, Kwang Meng, is bound both by filial duty and his meagre circumstances in a dead-end job as a clerk to fulfil his role as sole breadwinner. In a futile attempt to escape the anxiety and insecurity of his situation, Kwang Meng tries to brush away the shroud-like pall of ennui that hangs over him by frequenting nightspots, bars and brothels and retreating into the familiar comfort of the cinema or beach to fantasise and daydream.9 The restless anxiety and struggle to come to terms with one’s existence in a meritocratic and driven society that has no place for the weak and timid is a recurring motif in Goh’s later novels, Dance of Moths (1995) and Dance with White Clouds: A Fable for Grown-ups (2001).

Apart from his award-winning literary pursuits, Goh worked as a medical practitioner and held many honorary positions in the Singapore arts scene. As chairman of the National Theatre Trust Board between 1967 and 1972, he was responsible for the development of the arts and cultural policies of post-Independence Singapore, as well as the development of cultural institutions such as the Singapore National Symphony, the Chinese Orchestra and the Singapore Dance Company.

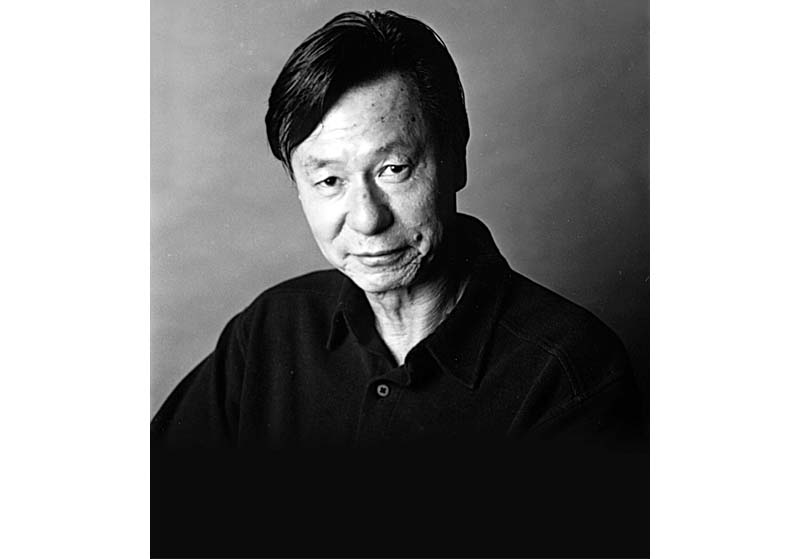

Goh Poh Seng was deeply involved in the development of Singapore’s arts and culture scene. Courtesy of Tribute.sg, an initiative by Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay and the Goh family.

Goh Poh Seng was deeply involved in the development of Singapore’s arts and culture scene. Courtesy of Tribute.sg, an initiative by Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay and the Goh family. The Singapore River after the removal of river craft such as tongkangs in 1984. Goh Poh Seng was involved in the redevelopment of Boat Quay in the 1980s. Today, the gentrified Boat Quay is a hub of bars, restaurants and cafés. Ronni Pinsler collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The Singapore River after the removal of river craft such as tongkangs in 1984. Goh Poh Seng was involved in the redevelopment of Boat Quay in the 1980s. Today, the gentrified Boat Quay is a hub of bars, restaurants and cafés. Ronni Pinsler collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Goh’s interests were not confined to just the highbrowed and cerebral. As a visionary cultural entrepreneur, Goh led the Boat Quay Conservation Scheme in the 1980s and crafted a blueprint for the development of Boat Quay into a vibrant lifestyle and entertainment area while preserving the historical buildings along the Singapore River. He also established Bistro Toulouse-Lautrec, a fashionable poetry-and-jazz café, and trendy Rainbow Lounge, Singapore’s first live disco and music venue.

Goh received the Cultural Medallion Award for Literature in 1982. In 1986, Goh and his family emigrated to Canada. While the reason for his abrupt departure from Singapore is well documented in newsprint – an alleged risqué remark made by a member of the house band at Rainbow Lounge led to the shutdown of the popular nightspot and heavy financial losses followed10 – the private strain of uprooting oneself from a much-beloved home and starting over in new country became apparent in several poignant stanzas of his later poetry.

A more intimate portrait of the poet is seen in a blog entry written by architect-poet Goh Kasan, the eldest son of the late Goh Poh Seng.11Goh Kasan revealed in his blog how his father’s businesses had failed in the 1980s, forcing their family overseas. More importantly, Goh Kasan described how the decision to leave Singapore changed their lives irrevocably. This critical move also raised questions in Goh Kasan’s younger self about the meaning of “home” and riddled his mind about the concept of a place he considers to be his home.

In a similar lament for “home”, some of Goh Poh Seng’s earlier poems, penned years before his move to Canada, chip away at the gleaming façade of this island nation to reveal the rusty framework of a “city that does not permit even a memory of the sky”. In his poem “Singapore”, we witness the relentless tide of changes that have swept through this country during its nation-building years; the poet laments the tainting of a simpler way of life, now threatened by the allure of commerce:

Towards the sea’s fresh salt

the river bears pollution

whose source was simple hills

Whose migration was tainted

when man

decided to dip his hand

Nourishing his wants

a commercial waterway

greased with waste

In the latter phase of Goh’s writing career, readers can detect an unmistakable transcendence in his works. A previously claustrophobic urban despondence seen in the troubled milieu of his earlier protagonists – the disillusioned office worker Kwang Meng in If We Dream Too Long and the intense but ineffectual advertising executive Ong Kian Teck in A Dance of Moths – thaws amid the peaceful acceptance of the flawed ways of the human condition, as seen through the travails of the unnamed elderly protagonist in Dance with White Clouds.

Where Goh’s travels had previously served as a catalyst for artistic change and as a means of breaking free from stubborn cognitive and behavioural habits,12 his permanent move overseas afforded him the luxury of renewing his commitment as a writer who was free to explore his new environs while continuing to search for his place in the larger scheme of things.13

More importantly, the suffocating and restless anxiety looming over his earlier protagonists in If We Dream Too Long and Dance of Moths gives way to a tranquil optimism in Dance with White Clouds, as seen through the unnamed wealthy but ageing protagonist’s sense of equilibrium and equanimity during a moment of spiritual epiphany – a departure from the somewhat pessimistic plots of his earlier novels:14

Then, during one night of night-long rain, alone in his room, listening to the monotonous drumming, to the anxious wind flapping the blind against the window sill, he found what he was looking for. He suddenly understood that there indeed was nothing to understand, that this was what all the wise men and sages of all the ages, what all the poets from time immemorial railed against, lamented – that there was nothing to understand, that it was impossible to know the unknowable…In extension, he had been wrong to feel that he had squandered his life, that it had been badly lived, that he had failed. Indeed, he had tried to love the whole world, and it was all right to live a life burdened with the love of family, children, friends, strangers. That night, he lost his fear, his anguish.

In a 2007 news article about Goh’s visit to Singapore for the first time in 21 years following his move to Canada, he was quoted as saying that he would have taken like a “duck to water” when asked if he could ever live in Singapore again.15 This was as fitting a denouement as one could expect for a diasporic homegrown writer who has left an indelible imprint on the nation’s works-in-progress mapping of its literary and cultural boundaries.

Identity in a Global World

Following the throes of nation-building in the post-Independence years, Singapore’s push to become a global city is seen to be the next logical step in its continuing reinvention. In 2000, the Renaissance City Report, which elaborated on the idealised vision of Singapore as a global city for the arts and creative industries, was published. Aiming to provide “cultural ballast” to the Republic’s initiatives at strengthening its national identity, the report articulated a plan to forge an environment that was “conducive to innovations, new discoveries and the creation of new knowledge” as part of a holistic plan for long-term sustained growth.16

To fulfil this vision, the state provided resources to fund arts and cultural infrastructure and education such as the performing arts venue Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay, with a view to providing a platform for crowd-pulling international acts. While these laudable state-sponsored initiatives have been greeted with enthusiasm from various sectors, the juxtaposition of artistic endeavours alongside perceived commercial viability has also been a point of contention for many. The well-meaning administration’s tireless efforts are seen to be short-circuiting its own attempt to nurture the Singapore artistic milieu by its preference for fast and visible shows of action and its emphasis on institutional “impact value”.17 The sad fact is that even arts administrators have to maximise returns for every dollar spent.

And to what extent does state policy affect the “Renaissance Singaporean” – called to be a model “active international citizen” who is expected to exhibit urbane sophistication yet simultaneously displaying the “Made in Singapore” label in the age of globalisation? The result is a curious hybrid citizen who feels at ease negotiating and finding his or her place in an increasingly borderless world – and simultaneously ill at ease as the individual grapples with issues of identity formation within a globalised paradigm.18

The main character in Hwee Hwee Tan’s novel Mammon Inc., Chiah Deng Gan, is a fresh graduate from Oxford who is caught between the comforting offer of a research assistant position and the prospect of a lucrative job as an Adapter – a person who assists high-flyers from the world over adapt to different cultures in order to excel at their professions – at the sinister transnational set-up Mammon CorpS, a subsidiary of Mammon Inc, a larger global corporation with tentacles that reach every corner of the world. But Chiah has to succeed at three tasks in order to be recruited. The first is to become accepted as a member of the uber-chic Gen Vex in New York, the second is to transform her British boyfriend Steve so that he can pass off as a Singlish-speaking Singaporean, and the last is to help her dyed-in-the-wool Singaporean sibling Chiah Chen gain acceptance into the Oxford milieu.

As Chiah Deng navigates her way in a transnational paradigm and mingles with the cosmopolitan Gen-Vexers who identify themselves with the latest fashion and gadgets, she finds herself drawn siren-like into the embrace of a formless consumerist entity. At the end of the story, Chiah Deng chooses to be a member of the diabolical global corporation, thus sealing her Faustian pact in a modern morality play. Chiah Deng’s choice plays up the difficult dilemma of how to become an effective citizen of the globalised world and yet retain ties to one’s homeland.19 It is no coincidence that Mammon’s Singapore-born author Hwee Hwee Tan was educated in both the United Kingdom and the US; hence her oeuvre can be read as a reflection of her personal experiences outside Singapore.20

Hwee Hwee Tan is the author of Foreign Bodies (1997) and Mammon Inc. (2001).

Hwee Hwee Tan is the author of Foreign Bodies (1997) and Mammon Inc. (2001).Another voice of conscience is Singapore-born poet Boey Kim Cheng who emigrated to Australia in 1997. Hailed as the “best post-1965 English language poet in the Republic”,21 Boey’s poetry veers between a private, introspective world of almost spiritual contemplation and public engagement with his immediate surroundings. The poet’s voice echoes his dislocation in a nation that is dedicated to economic growth, success and efficiency, and one of the ways he can resist the state’s invasive reach is to travel overseas.22

But even while the poet’s journeys abroad bring welcome relief, he experiences a profound sense of loss as the city-state vigorously pursues urban renewal at the expense of familiar landmarks. In the poem, Change Alley, Boey expresses a deep desolation at the transformation of the iconic commercial site by describing how the “streets lost their names/ the river lost its source” and the alley has “followed the route to exile”. The poet arrives at a rather poignant conclusion as he connects his isolation from the nation’s aspirations with these bittersweet words, “I am not at home, anywhere.”23

In his later works written after emigrating to Australia, Boey makes the proverbial journey back to Singapore in search of his childhood memories, journeying in particular to find the lost father figure of his youth. He finds a somewhat happy closure in the poem, Plum Blossom or Quong Tart at the QVB, as he draws a parallel between the famous Chinese migrant Quong Tart, featured in an exhibition on Australian multiculturalism, and his own father who shares the same family name. The poet sees a striking similarity in Quong Tart’s visage and that of his father’s, and goes a step further to speculate that the migrant might have been related to his ancestors:

Perhaps great-grandfather sallied forth / with Quong Tart on the same junk, / and disembarked in Malaya, while Quong Tart / continued south. Perhaps they were brothers.

The imaginary narrative gives the poet a sense of belonging and binds the diasporic trajectories of the Boey’s ancestor and Quong Tart, enabling the poet to project their divergent yet similar personal histories onto a single tapestry. Emigration entails bidding farewell to one’s homeland and all three men share the same “family history” but the poet is comforted that his daughter’s tracing of the pictograms in her Chinese name reconnects an earlier diasporic tale and makes meaning of the present.

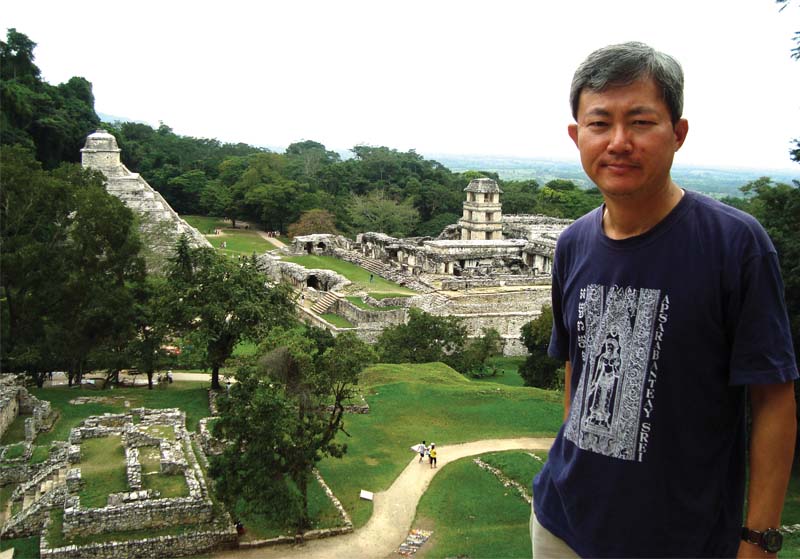

Award-winning writer Boey Kim Cheng in Palenque, Mexico. His latest works include Between Stations (2009) and Clear Brightness (2012). Courtesy of Boey Kim Cheng.

Award-winning writer Boey Kim Cheng in Palenque, Mexico. His latest works include Between Stations (2009) and Clear Brightness (2012). Courtesy of Boey Kim Cheng.In conclusion, while poets articulated their views in purpose-driven public or personal verses in the period immediately after Independence and during the nation-building years, alternative voices of the Singapore diaspora spoke with a measured calm, contemplating the imprints made by national policies and initiatives. Their refreshing perspectives continue to push the creative boundaries as the Republic finds its footing in this era of globalisation and transnationalism.

Michelle Heng is a Librarian with the National Library of Singapore. She compiled and edited Singapore Word Maps: A Chapbook of Edwin Thumboo’s New and Selected Place Poems and more recently, Selected Poems of Goh Poh Seng. She was also the co-compiler and joint editor of Edwin Thumboo – Time-travelling: A Selected Annotated Bibliography.

REFERENCES

Goh, P.S. (2010). If we dream too long. Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING S823 GOH)

Goh, P.S. (1976). Eyewitness. Singapore: Heinemann Educational Books. (Call no.: RSING 828.995957 GOH)

Goh, P.S. (1995). A dance of moths. Singapore: Select Books. (Call no.: RSING S823 GOH)

Gretchen, M. (1983, May 8). Boat Quay’s businessman and poet. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Gwee, L.S., & Thumboo, E. (Eds.). Sharing borders: Studies in contemporary Singaporean-Malaysian literature II. Singapore: National Library Board, National Arts Council. (Call no.: RSING S820.9 SHA)

Heng, M., & Gwee, L.S. (Eds.). (2012). Edwin Thumboo: Time-travelling: A select annotated bibliography (p. 32). Singapore: National Library Board. (Call no.: RSING S821 EDW)

Goh, K.S. (2011). Home: A loaded world. In Dias-Pura. Retrieved from gohkasan wordpress website.

Koh, B.S. (1996, September 9). Bleak vision of man trapped in futile quest. The Straits Times, p. 18. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Koh, J.L. (2013, October 4). Erratic as thoughts: Goh Poh Seng’s lines from Batu Ferringhi. Quarterly Literary Review Singapore, 12 (4).

Lim, S. (1996, November 2). Singapore: Too much presence for young. The Straits Times, p. 25. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Mohammed A. Quayum, Wong, P.N., & Thumboo, E. (Eds.). (2009). Sharing borders: Studies in contemporary Singaporean-Malaysian literature I. Singapore: National Library Board, National Arts Council. (Call no.: RSING S820.9 SHA)

National Library Board. (2005). Literature development. Retrieved from NLB exhibitions website.

Phair, D. (2001, May 19). Living in exile, but the Dance never ends. The Straits Times, p. 21. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Poon, A., & Holden, P. & Lim, S.G-L. (Eds.). (2009). Writing Singapore: An historical anthology of Singapore literature. Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING S820.8 WRI)

Tay, E. (2011). Colony, nation, and globalisation: Not at home in Singaporean and Malaysian literature. Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING S820.9 TAY)

Thumboo, E., & Sayson, R.I. (2007). (Eds.). From the inside: Asia Pacific literature in Englishes (Vol. 1). Singapore: Ethos Books. (Call no.: RSING 427.95 WRI)

Yap, S. (2007, November 18). A pioneer returns home. The Straits Times, p. 70. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

NOTES

-

Wong, P.N. (2009). In the beginning: University Verse in the first decade of the University of Malaya (pp. 76–77). In Mohammed A. Quayum & P.N. Wong, (Eds.), Sharing borders: Studies in contemporary Singaporean-Malaysian literature 1. Singapore: National Library Board, National Arts Council. (Call no.: RSING S820.9 SHA) ↩

-

National Library Board. (2005). Literature development. Retrieved from NLB exhibitions website. ↩

-

Tay, E. (2011). Nationalism and literature: Two poems concerning the Merlion and Karim Raslan’s “Heroes” (p. 79). In Colony, nation, and globalisation: Not at home in Singaporean and Malaysian literature. Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING S820.9 TAY) ↩

-

Poon, A., & Holden, P. & Lim, S.G-L. (Eds.). (2009). Section 2, 1965–1990: Introduction (p. 174). A. Poon, P. Holden & S.G-L. Lim. (Eds.), Writing Singapore: An historical anthology of Singapore literature. Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING S820.8 WRI) ↩

-

Heng, M., & Gwee, L.S. (Eds.). (2012). Biography (p. 32). In Edwin Thumboo: Time-travelling: A select annotated bibliography. Singapore: National Library Board. (Call no.: RSING S821 EDW) ↩

-

Heng & Gwee, 2012, p. 82. ↩

-

Lee, A.S.Y. (2009). Caught between earth and sky: The life and works of Goh Poh Seng (p. 213). In Mohammed A. Quayum & P.N. Wong, (Eds.), Sharing borders: Studies in contemporary Singaporean-Malaysian literature 1. Singapore: National Library Board, National Arts Council. (Call no.: RSING S820.9 SHA) ↩

-

Goh, K.S. (2011). Home: A loaded world. In Dias-Pura. Retrieved from gohkasan wordpress website. ↩

-

Koh, J.L. (2013, October 4). Erratic as thoughts: Goh Poh Seng’s lines from Batu Ferringhi. Quarterly Literary Review Singapore, 12 (4). ↩

-

Yap, S. (2007, November 18). A pioneer returns home. The Straits Times, p. 70. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Poon, A., & Holden, P. & Lim, S.G-L. (Eds.). (2009). Section 3, 1990: Present: Introduction (pp. 361–362). In Writing Singapore: An historical anthology of Singapore literature. Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING S820.8 WRI) ↩

-

Gwee, L.S. (2007). Two renaissances: Singapore’s new poetry and its discontents (Vol. 1; p. 202). In E. Thumboo & R.I. Sayson. (Eds.). Thumboo, E., & Sayson, R.I. (2007). (Eds.). From the inside: Asia Pacific literature in Englishes. Singapore: Ethos Books. (Call no.: RSING 427.95 WRI) ↩

-

Tay, E. (2011). Two Singaporeans in America: Hwee Hwee Tan’s mammon Inc., and Simon Tay’s alien Asian (p. 121). In Colony, nation, and globalisation: Not at home in Singaporean and Malaysian literature. Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING S820.9 TAY) ↩

-

Lim, S. (1996, November 2). Singapore: Too much presence for young. The Straits Times, p. 25. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Brewster, A. (2009). The traveller’s dream: Nation and diaspora in the work of Boey Kim Cheng (Vol. 2; p. 127). In L.S. Gwee (Ed.), Writing Asia: The literatures in Englishes. Singapore: Ethos Books. (Call no.: RSING 820.9 SHA) ↩