Tales of the Dragon’s Tooth Strait

Lee Meiyu offers us a glimpse of pre-colonial Singapore as seen through the eyes of the 14th-century Chinese traveller Wang Dayuan.

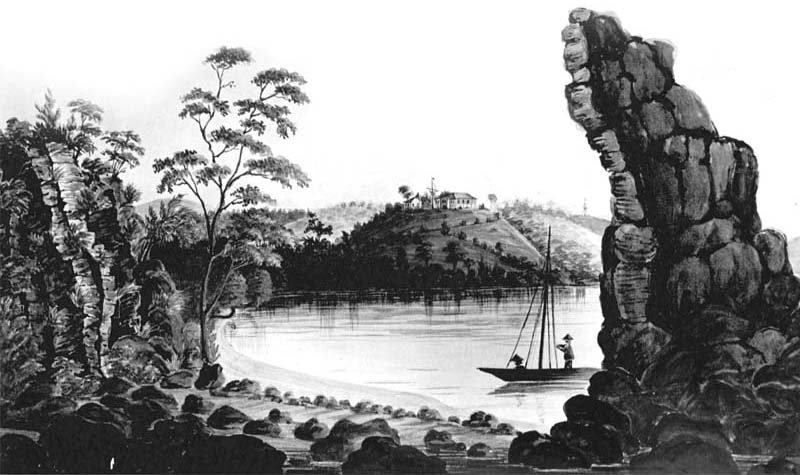

Lot’s Wife and W. W. Ker’s house on Bukit Chermin in 1845 or 1848. Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

Lot’s Wife and W. W. Ker’s house on Bukit Chermin in 1845 or 1848. Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.“The strait runs between the two hills of the Tan-ma-hsi barbarians, which look like ‘dragon teeth’. Through the centre runs a waterway. The fields are barren and there is little padi. The climate is hot with very heavy rains in the fourth and fifth moons. The inhabitants are addicted to piracy. In ancient times, when digging the ground, a chief came upon a jewelled head-dress. The beginning of the year is calculated from the [first] rising of the moon, when the chief put on his head-gear and wore his [ceremonial] dress to receive the congratulations [of the people]. Nowadays this custom is still continued. The natives and the Chinese dwell side-by-side. Most [of the natives] gather their hair in chignons, and wear short cotton bajus girded about with black cotton sarong.

“Indigenous products include coarse lakawood and tin. The goods used in trade are red gold, blue satin, cotton prints, Ch’u [chou-fu] porcelain, iron caldrons and suchlike things. Neither fine products nor rare objects come from here. All are obtained from intercourse with Ch’üan-chou traders.

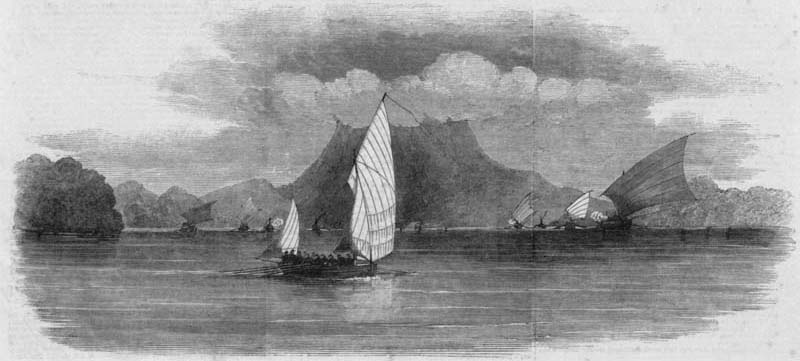

“When junks sail to the Western Ocean, the local barbarians allow them to pass unmolested but when on their return the junks reach Chi-limen (Karimon), [then] the sailors prepare their armour and padded screens as a protection against arrows for, of a certainty, some two or three hundred pirate prahus will put out to attack them for several days. Sometimes [the junks] are fortunate enough to escape with a favouring wind; otherwise the crews are butchered and the merchandise made off within quick time”.1

Print from Illustrated London News showing Her Majesty’s ship, Royalist, being chased by a fleet of Malay pirates at Endeavour Straits (near Palawan Island), drawn by Captain Bate of the Royalist. The highland in the background is Malampaya Table (1852). Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Print from Illustrated London News showing Her Majesty’s ship, Royalist, being chased by a fleet of Malay pirates at Endeavour Straits (near Palawan Island), drawn by Captain Bate of the Royalist. The highland in the background is Malampaya Table (1852). Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Piracy, pillage, ancient rituals and barbarians – hardly a picture associated with the soaring skyscrapers and success of modern Singapore. Yet, this is how Wang Dayuan (汪大渊), the intrepid 14th-century traveller from Quanzhou (泉州), China, describes Dragon’s Tooth Strait (龙牙门or Longyamen), a place now identified as the western entrance of Keppel Harbour in former times.2

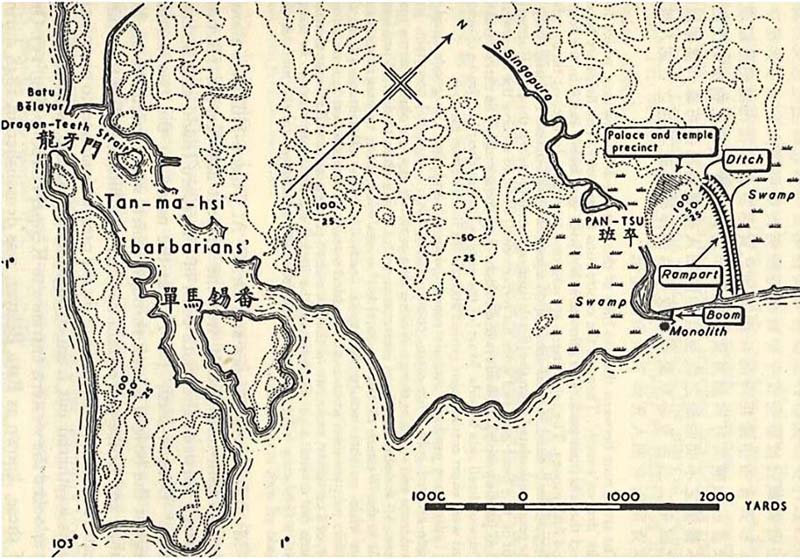

Dragon’s Tooth Strait refers to a sailing route commonly used by traders travelling from Europe and the Middle East to China and vice versa. It is situated between Labrador Point and Fort Siloso. The term Dragon’s Tooth refers to a prominent rock that once overlooked the entrance of the waterway. Also known as Batu Berlayar and Lot’s Wife,3 the rock was demolished in the mid-19th century to widen the waterway for the passing of steamships.4

Apart from the Dragon’s Tooth Strait, Singapore was mentioned twice more in Wang’s well-known 1350 publication, Description of the Barbarians of the Isles in Brief (《岛夷志略》or Dao Yi Zhi Lue). The other two entries are about Banzu (Fort Canning Hill) and an attack by the people of Siam. Banzu is described as such:

“This locality is the hill behind Longyamen. It resembles a truncated coil. It rises to a hollow summit [surrounded by] interconnected terraces, so that the people’s dwellings encircle it. The soil is poor and grain scarce. The climate is irregular, for there is heavy rain in summer, when it is rather cool. By custom and disposition [the people] are honest. They wear their hair short, with turbans of gold-brocaded satin and red oiled-cloths [covering] their bodies. They boil sea-water to obtain salt and ferment rice to make spirits called ming-chia. They are under a chieftain. Indigenous products include very fine hornbill casques, lakawood of moderate quality and cotton. The goods used in trading are green cottons, lengths of iron, cotton prints of local manufacture, ch’ih chin ,5 porcelain ware, iron pots and suchlike”.6

Thirteenth to 14th-century gold ornaments, coins and porcelains found during archaeological digs at Fort Canning Hill suggest the presence of an affluent community in the area. When compared to findings in sites near the mouth of the Singapore River, it is clear that the objects discovered at Fort Canning Hill are generally of finer quality.7 This supports Wang’s 14th-century descriptions of two communities of different economic status living on the same island of Singapore: one community “addicted” to piracy and the other rich enough to wear “gold-brocaded satin”.

In another write-up under the entry “Siam”, an attack on Temasek (old Singapore) is described:

“In recent years, they [Xian ‘people of Shan/Siam’] came with 70-odd junks and raided Dan-ma-xi (Temasek) and attacked the city moat. [The town] resisted for a month, the place having closed the gates and defending itself, and they not daring to assault it. It happened just then that an Imperial envoy was passing by (Dan-ma-xi), so the men of Xian drew off and hid, after plundering Xi-li”.8

Historian Dr John N. Miksic believes the old city walls documented by John Crawfurd – a British East India Company diplomat and administrator who later became the second Resident of Singapore – on his morning stroll around the Fort Canning Hill area to the Singapore River in 1821 were the former boundaries of the city supposedly targeted by Siam. The walls were said to be 2.5 metres tall with a stream running next to it, although no signs of a gate has ever been found.9 If this is true, it would mean that the settlement at Banzu was the city attacked by Siam in Wang’s account.

Miksic also believes banzu is a transliteration of the Malay word pancur, meaning “spring of water”. When the British arrived in Singapore, the locals told them about the forbidden spring behind Fort Canning Hill where the consorts and wife of the king bathed. The British later used the spring as a freshwater supply source for ships visiting Singapore. As demand for freshwater rose after 1830, a series of wells were dug around the foot of the hill to increase water supply and the spring dried up.10

The three entries documented by Wang Dayuan depicted 14th-century Singapore as home to both a pirate lair and a rich community – possibly the ruling royalty – living on the same island. Archaeological findings and comparisons with other ancient texts from Malay, Portuguese and Dutch sources of the time have verified the accuracy of Wang’s descriptions.11

Wang’s detailed observations also reveal the different attires worn by locals as well as the goods traded, indicating that 14th-century Singapore was, if not a bustling port city by then, a strategically located island with two distinctly different settlements at Longyamen and Banzu respectively. Suffice it to say, the reputation that Singapore enjoyed at the time was enough to attract the attention of Siam who launched their attack on the island with its fleet of 70-odd junks. The settlement at Banzu must have been a well-fortified town to be able to withstand the month-long siege.

Early texts such as Wang Dayuan’s travel accounts are important in the study of Singapore’s pre-colonial history. The Bugis, Siamese, Malay, Arabs and Chinese were active in Southeast Asia’s waters long before the European powers (Portuguese, Dutch and British) were involved in the power struggle for the region’s trade and hegemony. Fortunately, Chinese sources have been relatively well-documented and maintained, thus ensuring the survival of important ancient texts and offering us a glimpse into Singapore’s past.

Map of the environs of ancient Singapore. Based on descriptions in the Dao Yi Zhi Lue, the Sejarah Melayu, and on remains still visible at the beginning of the 19th century.12 All rights reserved. The Golden Khersonese: Studies in the historical geography of the Malay Peninsula before A.D. 1500, 1961, Wheatley, P., University of Malaya Press, Kuala Lumpur.

Map of the environs of ancient Singapore. Based on descriptions in the Dao Yi Zhi Lue, the Sejarah Melayu, and on remains still visible at the beginning of the 19th century.12 All rights reserved. The Golden Khersonese: Studies in the historical geography of the Malay Peninsula before A.D. 1500, 1961, Wheatley, P., University of Malaya Press, Kuala Lumpur.

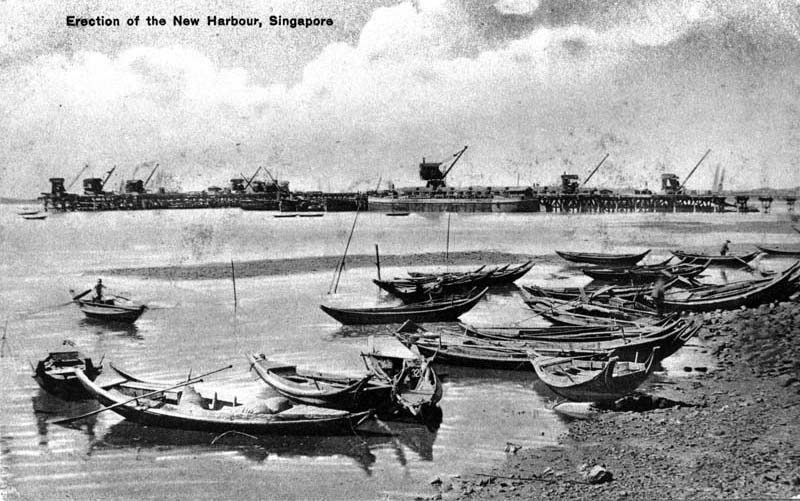

Construction of the new harbour in the 1880s, which was renamed Keppel Harbour in 1900. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Construction of the new harbour in the 1880s, which was renamed Keppel Harbour in 1900. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

WHO WAS WANG DAYUAN?

Wang Dayuan, also known as Huanzhang (焕章), was born around 1311 in Nanchang (南昌), a prosperous port in Jiangxi (江西) Province, Quanzhou, China.13 He was the first Chinese to write extensively about Southeast Asia based on his personal experiences and published them in Dao Yi Zhi Lue (《岛夷志略》or Description of the Barbarians of the Isles in Brief). Before Wang’s book, there were several travel accounts written by others. However, these accounts were either based on hearsay or not as extensively documented as Wang’s list of 99 locations.14 Furthermore, Wang’s book contains the earliest surviving eyewitness account of ancient Singapore.15 These factors make Dao Yi Zhi Lue a valuable source on the pre-colonial history of Southeast Asia and Singapore.

Wang’s book was originally published in 1349 as an appendix in a local gazetteer Qing Yuan Xu Zhi (《清源续志》or A Continuation of the History and Topography of Quanzhou) by Wu Jian (吴鉴). In the preface, Wu stated that Wang travelled overseas twice and the account was a result of Wang tidying his notes written during the course of his two trips.16 Scholars have placed the years of the trips around 1330 and 1337 respectively.17

In his own postscript, Wang stated that the 1349 edition was known as Dao Yi Zhi (《岛夷志》or Description of the Barbarians of the Isles). Another preface written by Zhang Zhu (张翥) relates that the account was re-published as a standalone travel account in 1350 in Nanchang, China. This particular edition is known as Dao Yi Zhi Lue.18

Lee Meiyu is a Librarian with the National Library of Singapore. She is co-writer of publications such as Money by Mail to China: Dreams and Struggles of Early Migrants and Roots: Tracing Family Histories – A Resource Guide.

REFERENCES

Chung, C.K. (2005). Longyamen is Singaproe: The final proof? In L. Suryadinata (Ed.), Admiral Zheng He & Southeast Asia. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. (Call no.: RSING 951.026 ADM)

Gibson-Hill, C.A. (1956, December). Singapore Old Strait & New Harbour 1300–1870. Memoirs of the Raffles Museum, 3. Singapore: G.P.O. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.52 BOG)

Hsu, Y.T. (1972, January). Singapore in the remote past. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 45, (1) (221), 1–9, pp. 3–4. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Kwa, C.G., Heng, D., & Tan, T.Y. (2009). Singapore, a 700-year history: From early emporium to world city. Singapore: National Archives of Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 959.5703 KWA)

林我铃著 [Lin, W.Z.0]. (1999). 龙牙门新考 : 中国古代南海两主要航道要冲的历史地理研究 [Long-ya-men reidentified: A historical geography study of two important junctions in the ancient Nanhai sea routes]. Singapore: South Seas Society. (Call no.: Chinese RSING 911.5 LWL)

Miksic, J.N. (2013). Singapore & the Silk Road of the sea, 1300–1800. Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 MIK)

Low, M.G.C–A. (2004). Singapore from the 14th to 19th century. In J.N. Miksic & M.G.C–A, Low, (Eds.), Early Singapore 1300s–1819: Evidence in maps, text and artefacts (pp. 16–17). Singapore: Singapore History Museum. (Call no.: RSING 959.5703 EAR)

Rockhill, W.W. (1915, March). Notes on the relations and trade of China with eastern archipelago and the coast of the Indian Ocean during the fourteenth century (Part II). T’oung Pao, second series, 16 (1), 61–159, pp. 129–132. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Su, J. (2000). Dao Yi Zhi Lue Jiao Shi [Annotations of Dao Yi Zhi Lue]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. (Not available in NLB’s holdings)

Wheatley, P. (1961). *The Golden Khersonese: Studies in the historical geography of the Malay Peninsula before A.D.1500. Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.5 WHE)

NOTES

-

Wheatley, P. (1961). The Golden Khersonese: Studies in the historical geography of the Malay Peninsula before A.D.1500 (p. 82). Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.5 WHE) ↩

-

Kwa, C.G., Heng, D., & Tan, T.Y. (2009). Singapore, a 700-year history: From early emporium to world city (p. 67). Singapore: National Archives of Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 959.5703 KWA) ↩

-

Miksic, J.N. (2013). Singapore & the Silk Road of the sea, 1300–1800 (p. 76). Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 MIK) ↩

-

Kwa, Heng & Tan, 2009, p. 66. ↩

-

Gibson-Hill, C.A. (1956, December). Singapore Old Strait & New Harbour 1300–1870. Memoirs of the Raffles Museum, 3, plate facing, (p. 66). Singapore: G.P.O. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.52 BOG) ↩

-

Low, M.G.C–A. (2004). Singapore from the 14th to 19th century. In J.N. Miksic & M.G.C–A, Low, (Eds.), Early Singapore 1300s–1819: Evidence in maps, text and artefacts (pp. 16–17). Singapore: Singapore History Museum. (Call no.: RSING 959.5703 EAR) ↩

-

Su, J. (2000). Preface. In Su Jing, Dao Yi Zhi Lue Jiao Shi [Annotations of Dao Yi Zhi Lue] (pp. 2–3). Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. (Not available in NLB’s holdings) ↩

-

Su, 2000, pp. 5–6. ↩

-

Su, J. (2000). Opening comments. In Su Jing, Dao Yi Zhi Lue Jiao Shi [Annotations of Dao Yi Zhi Lue] (pp. 10–11). Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. (Not available in NLB’s holdings) ↩

-

Su, 2000, pp. 1–2. ↩