Lee Kip Lin: Kampung Boy Conservateur

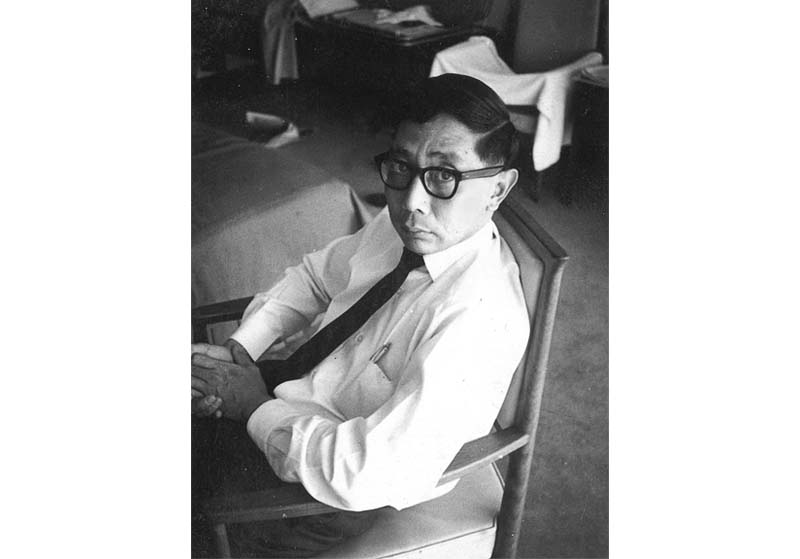

Lee Kip Lin in the early 1960s. Courtesy of Mrs Lee Li-Ming.

Lee Kip Lin in the early 1960s. Courtesy of Mrs Lee Li-Ming.The late Lee Kip Lin was a man who wore many hats as student, educator and mentor, but is perhaps best remembered for his passion for conserving Singapore’s pre-war architecture in his writings and teaching.

Despite his privileged upbringing and high standing in his profession as both architect and university lecturer, Lee was unassuming in his relationships with colleagues and students alike. His love for the local built landscape led him to meticulously photograph Singapore’s urban environment, street after street, eventually amassing not only photographs, but a precious collection of maps, postcards and other documents about Singapore – a collection his family generously donated to the National Library Board in 2009.

Lee the Student

Born in 1925, Lee was the fourth of five children1 and part of a distinguished Peranakan family that had a fine standing in the business community in Malaya. His paternal grandfather, Lee Keng Kiat, was manager of the Straits Steamship Company and was so highly regarded that he had a street (in Tiong Bahru) named after him. His businessman father, Lee Chim Huk, was known for his taste in the finer things in life. Always impeccably dressed and well-read, the elder Lee was likely to have influenced his son in appreciating aspects of life beyond the ordinary.2 His mother, Tan Guat Poh, was the younger sister of the business vanguard and political leader, Tan Cheng Lock, and one of the few educated local women during that era.

Lee had a creative bent from childhood but he was no quiet and self-absorbed artist. Golf and boating, twin passions he inherited from his father, kept him outdoors and active. In fact, some of his early childhood drawings were of passing ships and boats3 that he observed while growing up by the sea along Singapore’s East Coast.4 The Lee boys were given their own row boats5 and the family regularly took a small launch to family gatherings at their grandaunt’s, Mrs Lee Choon Guan (famous for her charity work, lavish parties and her family connections) seaside holiday home in Changi.6 Even in adulthood, Lee maintained his own boat, which his architectural students often used on their after-school escapades.7

Lee Kip Lin (centre) with his brother Kip Lee (right) and a neighbour on a boat just off their family home in Amber Road, Katong, circa 1935. Courtesy of Mrs Lee Li-Ming.

Lee Kip Lin (centre) with his brother Kip Lee (right) and a neighbour on a boat just off their family home in Amber Road, Katong, circa 1935. Courtesy of Mrs Lee Li-Ming.Lee came into his profession almost by accident. His academic records were poor because his education was disrupted by the war. As he prepared to further his studies in London in 1948, Lee’s mother advised him to pursue a degree in agriculture, promising him land upon completion of his studies. But Lee’s passion for sketching led him to seek a placement in architectural studies instead. Unfortunately, his lack of a foundation in science saw him rejected by 20 universities before he was finally accepted by the Brixton School of Building in London. The polytechnic gave him a good grounding in technical skills but he sought a more professional training in architecture. Not one to give up easily, Lee reapplied to London’s Bartlett School of Architecture, famed for its Beaux Arts approach – a French neo-classical perspective of architecture that would later influence Lee’s approach to architecture in Singapore. Lee had failed an entrance test the previous year when he was asked to sketch a building from memory and, unprepared, he submitted a poor sketch of the 1926 neo-classical College of Medicine building.8 In his second attempt, Lee drew the Pantheon in Rome, so well executed that it even gained the invigilator’s attention.9

During his six-year study at Bartlett, Lee was influenced by architectural greats such as William Holford (1907–1975), a noteworthy town planner; A. E. Richardson (1880–1964), an expert in the art of architecture especially of the Renaissance period; and Hector Corfiato (1893–1963?),10 Richardson’s protégé who later took over as Bartlett’s Professor of Architecture. Lee had expressed regret that much of his time was spent socialising at bars rather than drinking in Europe’s architectural heritage.11

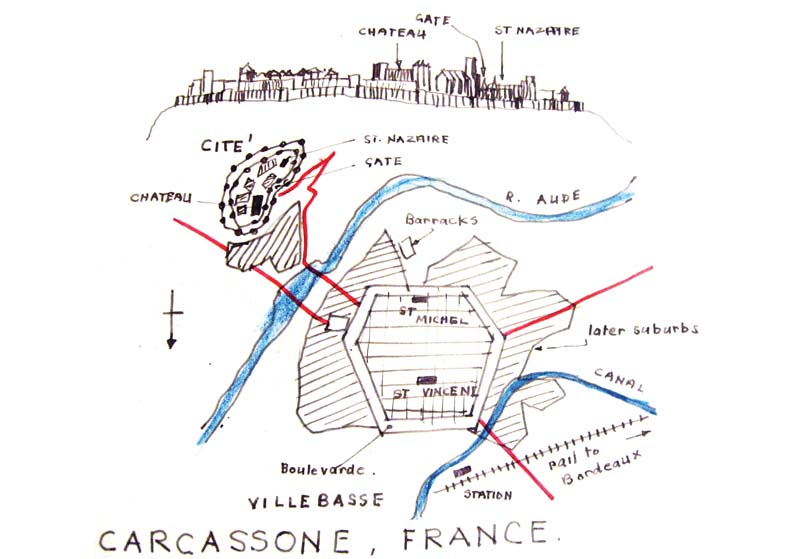

Lee Kip Lin’s sketch of Carcasonne, France, copied from Taylor, G.‘s Urban Geography (1951), which shows off some of his drawing skills. From the Lee Kip Lin Collection. All rights reserved. Lee Kip Lin and National Library Board, Singapore 2009.

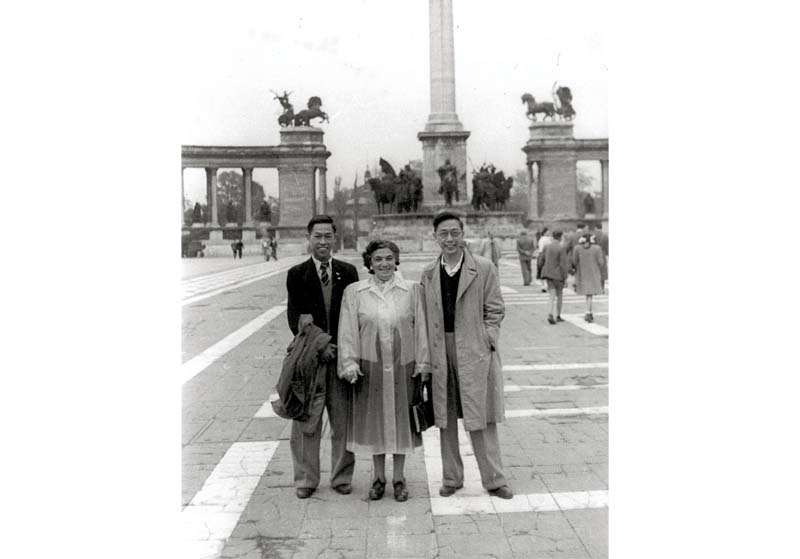

Lee Kip Lin’s sketch of Carcasonne, France, copied from Taylor, G.‘s Urban Geography (1951), which shows off some of his drawing skills. From the Lee Kip Lin Collection. All rights reserved. Lee Kip Lin and National Library Board, Singapore 2009. Lee Kip Lin (right) with friends in Paris circa 1950s. Courtesy of Mrs Lee Li-Ming.

Lee Kip Lin (right) with friends in Paris circa 1950s. Courtesy of Mrs Lee Li-Ming.Lee the Architect

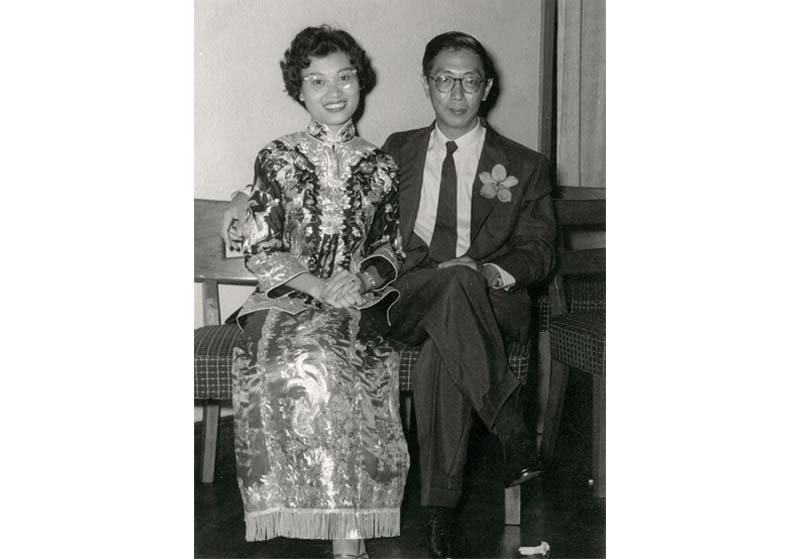

Lee returned to Singapore in October 1956, a time of political and social unrest as Malaya was actively defining its political boundaries in its bid to gain independence from Britain. With a year’s experience at the Housing Division of the London County Council under his belt, Lee started work in 1957 as an Architectural Assistant to Wee Soo Bee before joining well-known architect Seow Eu Jin in 1958. The following year, in 1959, he married Li-Ming, daughter of H. T. Ong, the first Chief Justice of Malaya. Between 1960 and 1964, Lee worked with one of Singapore’s key architects, Ng Keng Siang who was highly regarded for creating many of the country’s landmark buildings such as the Singapore Badminton Hall (1952) at Guillemard Road and the former Asia Insurance Building (1954) in Finlayson Green (now converted into the serviced apartments Ascott Raffles Place).

Lee Kip Lin and his wife, Ong Li-Ming, married in 1959. Courtesy of Mrs Lee Li-Ming.

Lee Kip Lin and his wife, Ong Li-Ming, married in 1959. Courtesy of Mrs Lee Li-Ming.In 1965, Lee established his own company, Lee, Lim and Partners, which originally included David Lim and Whang Tar Kway. One of his company’s major accomplishments was winning the landmark Industrial Commercial Bank (ICB) project. The partnership dissolved soon after Lim Chin Leong’s death and Lee started the firm Silat12 Associates along with partner Lim Chong Keat, which had a tie-up with Architect Team 3 before Lee finally joined the latter.

Unfortunately, between 1960 and 1969, tumultuous times dogged the building industry. New projects for small companies were scant and sustaining an architectural firm proved financially challenging. Lee and his partners started concurrently working and lecturing, first at the newly established architectural schools at Singapore Polytechnic and, subsequently, the University of Singapore (now the National University of Singapore, NUS). Their pay packets were often shared among the partners, but they seldom saw any returns.

Lee the Lecturer

Lee began lecturing in architectural studies at Singapore Polytechnic in 1961, while the field was still in its infancy in Singapore. Prominent local architect Tay Kheng Soon (who designed People’s Park Complex and the Golden Mile Complex13) was one of the pioneer students of the polytechnic’s architecture faculty. This batch of students had been nicknamed “the horrors” as they had a reputation for being difficult. Lee was assigned to teach this class but cleverly won them over on the first day by offering his students sticks of Du Maurier’s14 cigarettes out of an elegant vermillion box. His unorthodox, relaxed style of teaching also helped him gain the trust of these mature students.

Lee’s experience in teaching ran almost concurrently with his years of practice, and he frequently made himself available to his students, seeming to find mentoring more fulfilling than running an architectural firm. In 1976, he was appointed senior lecturer at the Faculty of Architecture at NUS, having left full-time practice. Students regularly visited his home to discuss projects or to just hang out with him. His camaraderie with his students was well-known because of his unassuming nature and his fatherly concern as Tse Swee Ling recalls. Tse had not only been his student but had also been recruited into Lee’s company and followed in his footsteps, lecturing at the same faculty in NUS. Not one for seeking position or limelight, Lee retired two years after he was promoted to associate professor at NUS in 1982.

Lee and his architecture students at his Binjai Park home. Courtesy of Mrs Lee Li-Ming.

Lee and his architecture students at his Binjai Park home. Courtesy of Mrs Lee Li-Ming.Lee the Conservationist

Lee threw himself into the research and conservation of the local architecture he had lived and grown up with. In quick succession he published several books on the history of Singapore’s built landscape – Telok Ayer Market (1983), Emerald Hill: The Story of a Street in Words and Pictures (1984) and The Singapore House 1819–1942 (1988), a historical illustrated survey of the development of domestic architecture and its impact on Singapore house design; covering everything from English Georgian, Victorian Eclectic, Edwardian Baroque, and Modern International to the homegrown “Coarsened Classical” styles, the out-of-print book is now regarded a classic.

After Lee retired, he began systematically photographing, neighbourhood by neighbourhood and street by street, all the buildings that lined the roads in the city as well as landmarks in the outlying areas of the island. By this time, Lee had accumulated an extensive collection of heritage photographs, maps and postcards which he purchased over many years from antique dealers in London and other parts of the world. Lee battled ill health in his later years and passed away in 2011 after a bout of pneumonia. He was 86 years old when he died.

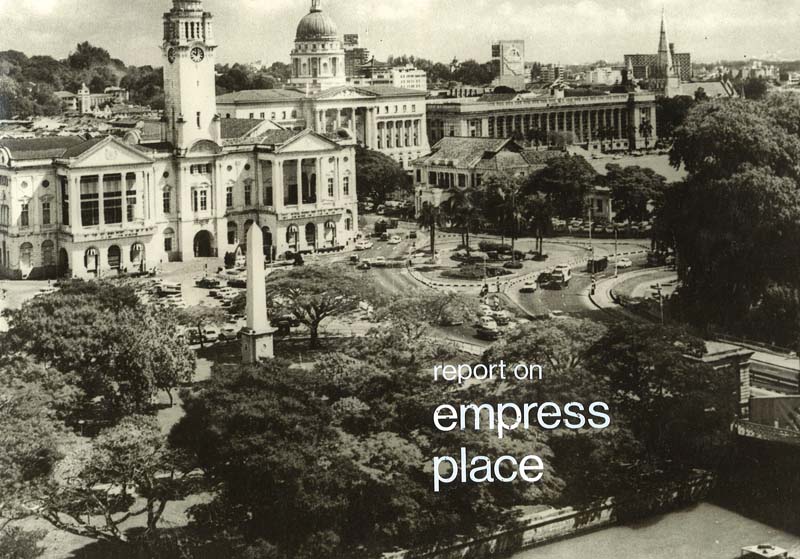

Report on Empress Place by Preservation of Monuments Board, 1973. A unique typescript publication in the Lee Kip Lin collection. From the Lee Kip Lin Collection. All rights reserved. Lee Kip Lin and National Library Board, Singapore 2009.

Report on Empress Place by Preservation of Monuments Board, 1973. A unique typescript publication in the Lee Kip Lin collection. From the Lee Kip Lin Collection. All rights reserved. Lee Kip Lin and National Library Board, Singapore 2009.The Lee Kip Lin Collection

In October 2009, the Lee family donated his extensive collection of more than 19,000 items to the National Library Board. It includes 1,322 monographs, 291 invaluable maps of Singapore and Southeast Asia, and 630 rare photographs along with more than 17,000 slides and negatives of early and modern Singapore, including many images of buildings that Lee had photographed in Singapore during the 1980s.

The collection’s strength lies in its visual documentation of the evolution of Singapore’s built environment. This thread linking its diverse formats and content reveals Lee’s passion for documenting Singapore’s vernacular architecture, particularly its classical and colloquial features. This is evident in his disciplined and systematic research as well as the details noted in his extensive photographic collection. For every street he documented, Lee would note the address and take multiple shots of its various buildings. His wife Lee Li-Ming, recounts how, on his retirement, Lee would spend his weekends visiting various areas in Singapore, map in hand, capturing buildings along each street with his camera.

Yet the Lee Kip Lin collection is not confined to the history of Singapore’s architecture. It extends into social and corporate histories, showing how Lee’s complex thinking went beyond the obvious. For example he collected several books on the histories of early shipping companies such as the Blue Funnel Line and the Straits Steamship Fleet. He also collected books and documents on the histories of various churches and local religious institutions.

Lee purchased much of his heritage books, postcards and photographs from antiquarian resellers in London and had them delivered to his Amber Road home. Others were gifted directly to him by the authors.15 Much of Lee’s handwritten research notes and sketches were bound and are now part of his donated collection. These include hand-copied paragraphs and sketches from some of his early studies of classical architecture as well as copied letters and records relating to significant people and places in Singapore. He regularly visited the National Archives and the National Library after his retirement, taking copious notes from hard-to-read manuscripts such as the Straits Settlement Records that outline the decisions and plans for streets in the early days of Singapore’s urban growth.

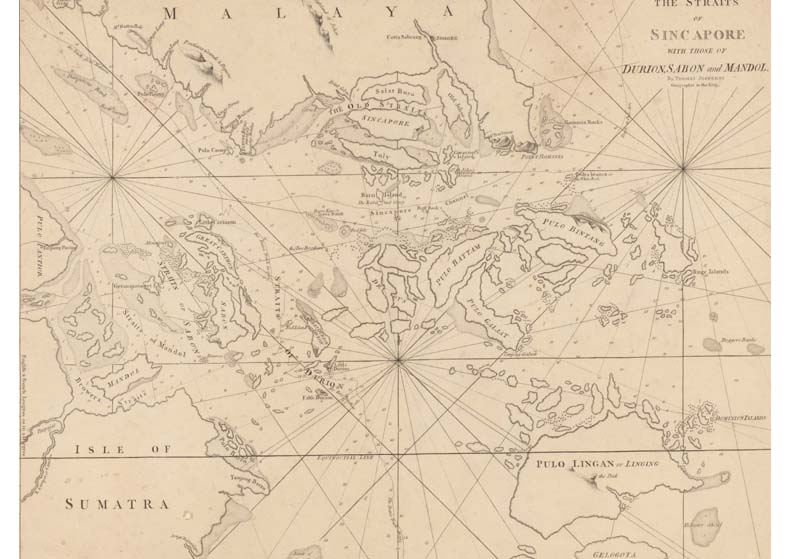

Lee’s map collection of 291 items is particularly valuable as they capture the cartographic narrative of Singapore as reflected by mapmakers over the centuries. One of the oldest maps in his collection, dated 179416 and drawn by the geographer to King George III, Thomas Jefferys, shows details of the Malay Peninsula and Singapore’s surrounding islands extending to the Carimon Islands and beyond. Interestingly the map shows not only how names of Singapore’s surroundings have changed or remained the same across the centuries, but also shows this island at an awkward angle. A large channel seems to cut through Singapore with its southern portion named “Toly”. This was a common error found in the earliest maps of Singapore and its interpretation is discussed at length by scholars like Gibson-Hill.17

The Straits of Singapore with those of Durion, Sabon and Mandol by Thomas Jefferys, Geographer to the King. From the Lee Kip Lin Collection. All rights reserved. Lee Kip Lin and National Library Board, Singapore 2009.

The Straits of Singapore with those of Durion, Sabon and Mandol by Thomas Jefferys, Geographer to the King. From the Lee Kip Lin Collection. All rights reserved. Lee Kip Lin and National Library Board, Singapore 2009. A navigational chart showing the Straits of Malacca and Malaya. Created by Bellin, Jacques Nicolas in 1775. From the Lee Kip Lin Collection. All rights reserved. Lee Kip Lin and National Library Board, Singapore 2009.

A navigational chart showing the Straits of Malacca and Malaya. Created by Bellin, Jacques Nicolas in 1775. From the Lee Kip Lin Collection. All rights reserved. Lee Kip Lin and National Library Board, Singapore 2009.Another 18th-century map by French cartographers reflects Singapore’s ancient name, Pulo Panjang, and shows elevated views of its surroundings, including Malacca. The map collection also bears several drawings of Malacca plan sketches from the colonial architectural firm Swan and Maclaren, and copies of various maps.

A large number of Lee’s maps date from the 19th century right into the pre-war era, from which the researcher can review the gradual urbanisation of Singapore, particularly his maps spanning the 1950s right into Independence in 1965. Besides revealing insights from individual maps, many of Lee’s maps are topographical records of urban as well as rural developments of Singapore. Interestingly, Lee has several maps reflecting the location of plantations in Singapore. Complementing these maps is a monograph with notes derived from records and documents giving details of these plantations. The map collection, when studied alongside his monographs, photographs and postcards, form a rich and multi-layered resource for the study of Singapore’s rural and urban landscapes.

LEE KIP LIN ON STUDYING ARCHITECTURE

I took architecture by accident … my mother … wanted me to do agriculture and she promised me that [if I] graduated, [she would] buy a piece of land somewhere…

I considered those [as] wasteful years [studying architecture in the UK]. Truly wasteful. I mean there I was drinking away… and Lim Chong Keat [a fellow student] was busily measuring buildings and photographing them. I took the whole thing [architectural studies] as a joke…

From an interview with Lee on 26 June 1985 by Tay Kheng Soon

PROFESSOR BOBBY WONG’S IMPRESSIONS OF LEE KIP LIN

I was assigned to teach with him … and he said, “Don’t worry, it’s my first time teaching too”. I asked him, “Oh, where were you practising before that?” And he said, “Team 3.” So I was really thrown off [as] Team 3 at that time was really the firm. There was something very informal [about LKL] and yet at the same time, from what he said, they were fairly insightful. He came across with no airs, nothing. But someone, you know who has so much history, so much background and yet so ordinary.

I was a young architect in a hurry to do international style of architecture. He [LKL] was someone who placed great importance in imparting to many around us the importance of the geography, the culture, the land and also the social and cultural life that came with this climate and this place.

From an interview with Prof Bobby Wong on 6 June 2012 by Bonny Tan

PROFESSOR TSE SWEE LING’S IMPRESSIONS OF LEE KIP LIN

I have known him for more than 40 years, from working in Team 3 to teaching in NUS. He’s really a good boss … whenever there was some argument, unhappiness amongst staff or whatever [in Team 3], he will always help to settle and he’s very good in human relationships. And the staff respect[ed] him.

His book, Singapore House, it’s not only about the architecture. He actually took the effort to find out about the lives of the people who lived there.

From an interview with Prof Tse Swee Ling on 6 June 2012 by Bonny Tan

The Lee Kip Lin collection can be accessed on PictureSG at http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/pictures. The publications are located in the donor collection at Level 13, but specific titles can be searched via the online OPAC and accessed directly from Level 11 counter.

Bonny Tan is a Senior Librarian with the National Library of Singapore. She has researched the Lee Kip Lin Collection over several years since it was first donated to the National Library Board. Her published work on the Baba Bibliography and the Gibson-Hill Collection amply qualify her to write on Lee’s life and his collection.

REFERENCES

Durai, J. (2011, July 15). Architect Lee Kip Lin dies. The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Gibson-Hill, C.A. (1954, May). Singapore: Notes on the history of the Old Strait, 1580–1850. Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 27 (1) (165), 163–214. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Lee, K.L. (1995). Amber sands: A boyhood memoir. Singapore: Federal Publications. (Call no.: RSING 920.71 LEE)

Low, L.L. (Interviewer). (1984, May 29). Oral history interview with Lee Kip Lin (Transcript of MP3 recording no. 000016/16/01, p. 1). Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website.

NUS Department of Architecture. (2011). NUS design (p. 322). Singapore: Department of Architecture, School of Design and Environment, National University of Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 720.7115957 NUSDA)

Lim, L., & Humphrey, N. (2005, October 26). One mad life story. Today, p. 46. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

National Library. (2011). Lee Kip Lin written by Tan, Joanna Hwang Soo. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website.

Tay, K.S. (1985, June 26). Oral history interview with Lee Kip Lin.

Tan, B. (2011, December 20). Oral history interview with Tay Kheng Soon.

Tan, B. (2011, December 22). Oral history interview with David Lim.

Tan, B. (2012, June 6). Oral history interview with Bobby Wong.

Tan, B. (2012, June 6). Oral history interview with Tse Swee Ling

Tay, S.C. (2010, June 12). A happy man of many words. The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Taylor, T.G. (1951). Urban geography: A study of site, evolution, pattern and classification in villages, towns and cities. London, Methuen; New York, Dutton. (Call no.: RDLKL 323.35 TAY)

NOTES

-

He had an older brother, Lee Kip Lee who had lived with an aunt at Cairnhill during his early childhood. Thus Lee Kip Lin was effectively the only son until his older brother returned to live with the family. Lee, K.L. (1995). Amber sands: A boyhood memoir (p. 23). Singapore: Federal Publications. (Call no.: RSING 920.71 LEE) ↩

-

He could distinguish the different types of sea vessels merely through their silhoutttes. Lee, 1995, pp. 22–23. ↩

-

Tay, oral interview ↩

-

This was the building Lee was most familiar with as he had ferried his sister to medical school regularly. The building in post-war Singapore was the Medical Faculty of the University of Malaya. (Tay, oral interview). ↩

-

Lee claimed the invigilator was David Aberdeen who had recently won a competition to design the Trade Union Congress building in London. He had sensed Aberdeen observing him sketching for at least 5 minutes during the exam (Tay oral interview) ↩

-

Derived from an article on Richardson, Albert Edward from a book he co-authored with Hector Cofiato. Retrieved from encyclopedia.com website. ↩

-

Tay, oral interview ↩

-

Silat is actually an acronym for Singapore, Lee Kip Lin and Architect Team 3 (Tse oral interview) ↩

-

Tay, S.C. (2010, June 12). A happy man of many words. The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

These are cigarettes out of Canada, a much sought after foreign brand at that time (Tay, oral interview) ↩

-

As seen in the personally signed books. Hall-John, J. (1995). The Horsburgh Lighthouse. Invercargill, N.Z.: John Hall-Jones. (Call no.: RSING 623.8942 HAL) ↩

-

Previous references that Joannes Theodore de Bry’s 1603 map of Singapore is the earliest in Lee’s collection is mistaken as the referred map is a reprint of the original. Even so, this map is an 18th century reprint of the original likely to have been made some time between 1766 and 1770 (Gibson-Hill, C.A. (1954, May). Singapore: Notes on the history of the Old Strait, 1580–1850. Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 27 (1) (165), 163–214, p. 187. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.) ↩

-

Gibson-Hill, May 1954, pp. 163–214. ↩