Raffles Hotel & the Romance of Travel

Gretchen Liu traces the history of this grand hotel, from its heyday of glitz and glamour to near ruin and its subsequent reincarnation into the heritage icon it is today.

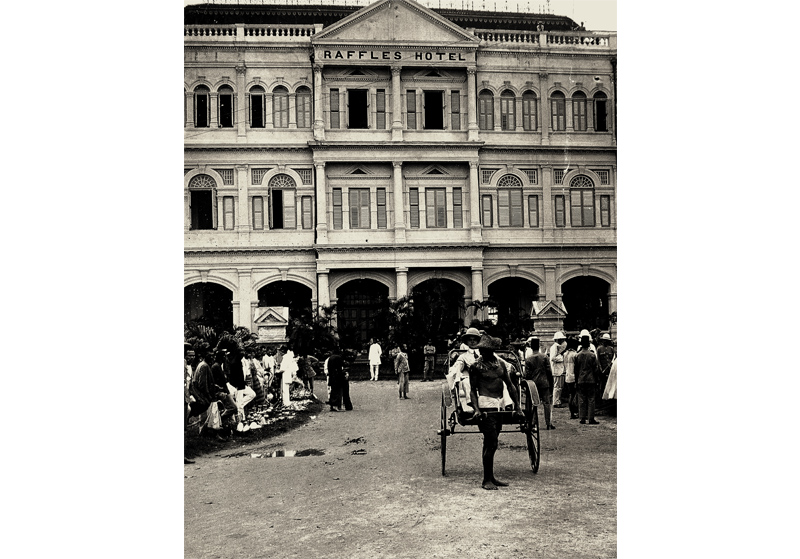

Jinrickshaws picking up travellers just outside Raffles Hotel, circa 1910. Courtesy of Raffles Singapore.

Jinrickshaws picking up travellers just outside Raffles Hotel, circa 1910. Courtesy of Raffles Singapore.For over a century, Raffles Hotel has shared Singapore’s prosperity and endured its vicissitudes, along the way becoming one of those rare places in the world where truth, legend, myth and mystery merge effortlessly together. The very name conjures up all that is romantic in travel. Over the years, the hotel has enjoyed several incarnations: modest start-up, grand caravanserai, fable-encrusted attraction, faded dowager, national landmark and restored beauty. The story of how Raffles Hotel became so celebrated, and how it survived when so many other hotels fell by the wayside, begins over a century ago and connects with the larger story of the “Golden Age of Travel” when, for the first time in human history, people began to circumnavigate the globe for the pleasure of taking in the sights.

Around World in 80 Days

First, a bit of early hotel history. From its earliest days as an outpost of the East India Company, Singapore offered a convenient port of call for European travellers. By the early 1840s, a range of accommodation was offered – the Ship Hotel, London Hotel, British Hotel, Commercial Hotel, Hotel de Paris, Hamburg Hotel – their names now only surviving in the pages of early newspapers. Yet business was difficult and unpredictable because travel was arduous and rarely for pleasure: the journey from London to Singapore via the Cape of Good Hope, for example, took about 120 days.

All that changed with the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, which, together with the appearance of steam-powered ships, shortened distances and sped up travel. The writer Joseph Conrad, who navigated the eastern seas as a young sailor in the 1880s, summed up the astonishing efforts of the canal’s opening in his novel The End of the Tether, writing that “like the breaking of a dam, [it] had let in upon the East a flood of new ships, new men, new methods of trade. It changed the face of the Eastern seas and the spirit of their life.”

Steamships not only sped up travel, they made it far more comfortable, and luxurious for some. By the 1890s, the oceans were circumnavigated by large coal-fed liners operated by companies such as the P&O, Straits Steamship, Messageries Maritimes, Lloyd Triestino and the Dutch KPLM. Add to these other late 19th century wonders – the telegram and telegraph, rising incomes and a growing middle class, the launch of travel as an industry by Thomas Cook – and the stage was set for the “Golden Age of Travel”.

Bradshaw’s, the authoritative guidebook publisher, announced not without a touch of incredulity in its 1874 edition of Through Routes, Overland Guide and Handbook to India, Egypt, Turkey, China, Australia and New Zealand that a traveller “may run through the Grand Tour of the Globe in an incredibly short time… he can accomplish a circuit of 23,000 to 23,500 miles in 78 to 80 days exclusively on mail steamers and trains”. Passengers were advised to take “their entire stock of clothing” with 336 pounds of luggage allowed for first class. A few bottles of good port and champagne were also recommended “in case of sickness and depression”.

Singapore was becoming an important coaling station for steamships. With more ships calling, decent hotel rooms were suddenly in short supply. By the 1880s, the port offered at least eight establishments – all located within a few blocks of the Padang in old bungalows to which various makeshift extensions had been added. The lack of something more elegant – a real grand hotel, which was even then a recent invention in the West – was cause for concern in the business community. An attempt was made to form a consortium to raise funds for a modern hotel but the capital investment proved too high and potential investors too few. Instead it was the Sarkies Brothers, Hotel Proprietors (as the company was called) that stepped into the void, intent on creating, in the Sarkies’ own words, “A really First Class Hotel”.

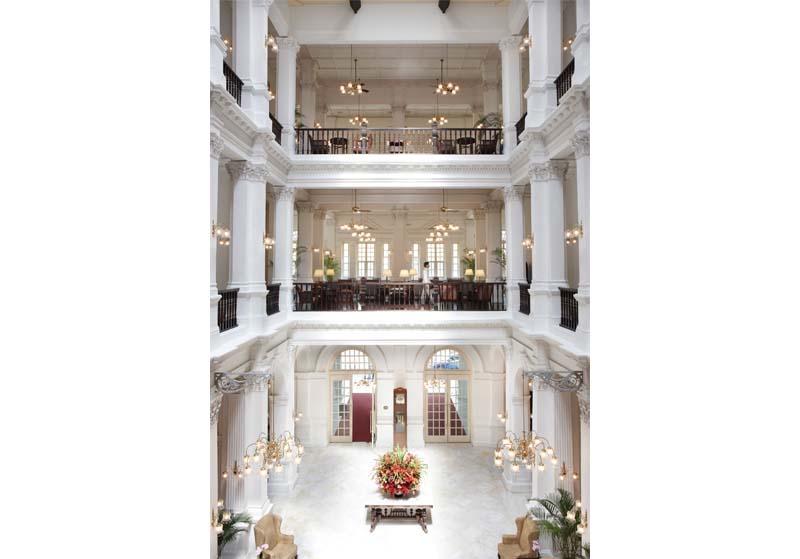

The revamped lobby of Raffles Hotel still exudes the grandeur of its heyday. Courtesy of Raffles Singapore.

The revamped lobby of Raffles Hotel still exudes the grandeur of its heyday. Courtesy of Raffles Singapore.Building a landmark: Raffles Hotel

In the early 1880s, two Sarkies brothers of Armenian descent, Martin and Tigran, had established themselves as hoteliers in Penang with two hotels, The Eastern and The Oriental (both hotels were later merged into one property, the Eastern & Oriental, E&O). When the Eastern Hotel landlord demanded a large increase in rent, they came to Singapore looking for an opportunity. They found it in the property at No 1 Beach Road, then known as Beach House, at the corner of Beach and Bras Basah roads. The bungalow was shabby but the grounds expansive, the location excellent, the sea view magnificent, and the landlord, Syed Mohamed Alsagoff, (see text box) supportive.

The modest 10-room Raffles Hotel opened to the public on 1 December 1887. As for the choice of name, “Raffles” was a particularly fashionable name that year: it was Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee year and to mark the event a statue of Sir Stamford Raffles had been unveiled on the Padang and the Raffles Library and Museum on Stamford Road had officially opened.

Tigran Sarkies proved to be a shrewd publicist. Two weeks before the hotel’s opening he shared his prediction of a brilliant future for the hotel in an advertisement. He highlighted the hotel’s location as “one of the best and healthiest in the island, facing the sea” and emphasised that “great care and attention to the comfort of boarders and visitors has been taken in every detail and those frequenting it will find every convenience and home comfort…”

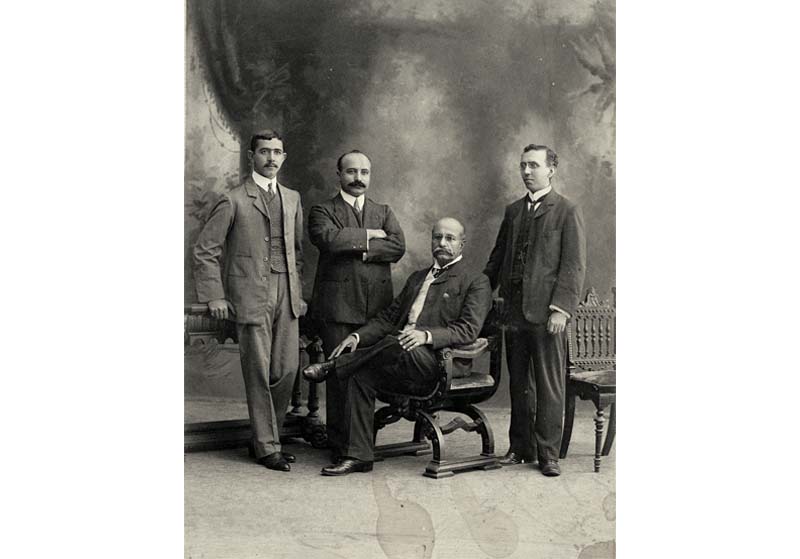

Eventually four brothers – Martin, Tigran, Aviet and Arshak – were involved in the family business during its early days. Mention has been made of Martin (1852–1912), an engineer and the first to arrive in Penang and Tigran (c1861–1912) who took charge of Raffles Hotel. Aviet (1862–1923), who first looked after the business in Penang when Martin retired, relocated to Rangoon, Burma, where he opened the Strand Hotel in 1899. Arshak (1869–1931) joined in 1890 and settled in Penang to oversee the E&O. Over the years, the brothers were associated with several other hotels in the Straits Settlements, including The Crag in Penang, and Grosvenor House and the Sea View in Singapore, but Raffles Hotel was the jewel and it was Tigran who nurtured it.

During Raffles Hotel’s first two decades, Tigran oversaw almost unabated construction. Three projects were completed in 1890: a pair of buildings comprising 22 suites flanking the old bungalow and the first iteration of the Billiard Room. In 1894, the Palm Court Wing was completed on the adjacent parcel of land at No 3 Beach Road, adding another 30 suites to the inventory.

The Main Building Opens in 1899

In 1899, the magnificent Main Building was constructed, replacing the original Beach House. The hotel’s grand opening in November was celebrated in style and secured Raffles’ status as a Grand Hotel. Beneath its elegant “Renaissance-style” exterior, the Main Building was thoroughly modern with its own generator, among Singapore’s first, powering electric lights, ceiling fans and a network of call bells. The design was unconventional as the ground floor was given over to the “Grand Marble Dining Saloon capable of seating 500”.

The upper two levels contained only 23 suites and were dominated by large Drawing Rooms, extending around the central atrium and across the entire front of the building. Comfortably furnished with writing tables and lounge chairs, the areas were ideal for reading, writing, socialising and enjoying cool sea breezes. Now this was a Grand Hotel. The façade of the Main Building soon became the “face” of the hotel, recognised worldwide, printed on luggage labels, engraved on stationery, photographed frequently and portrayed in a host of picture postcards.

The final building project was the Bras Basah wing, a further innovation in that the ground floor contained a row of shops. The 20 suites on the two floors above were accessible only from the main entrance. Its debut in 1904 secured Raffles’ status as the largest, and best, hotel in the Straits Settlements. Raffles was now at the pinnacle of its early heyday.

Tigran, ever the merchant, proudly, and often, advertised this fact: “First Class Travellers only… the Select Rendezvous of the East” (1904); “We set the pace and have our imitators” (1905); “The only Hotel of its Unique Style in the East and Renowned for its All Around Modern Comforts” (1909); “The Hotel that has made Singapore Famous to Tourists” (all this in the hotel’s own brochures). Tigran and his staff cultivated the burgeoning world cruise liner business with specially arranged dinners and grand balls. “Yearly between 50,000 and 60,000 guests sign their names in the hotel books,” proclaimed the compendium Present Day Impressions of the Far East in 1917.

In the minds of many, Raffles Hotel was now inexorably linked with Singapore as the great “Crossroads of the East”. As one traveller remarked in 1912, “Singapore is the only city which everyone encircling the globe is forced to visit, at least for a day.” The ritual of arrival was often described in early travel books, the first impression of lush coconut groves, mangrove swamps and coastal villages giving way to praise for the expanse of handsome buildings – Singapore’s own Bund – lining the shore as the town came into view. The large steamers operated by international companies moored at the expanded Tanjong Pagar Wharves, two miles from town. Smaller steamers handling regional routes discharged passengers in the open roadstead where they were ferried to Johnston’s Pier, later replaced by Clifford Pier.

Raffles’ management strived to stay ahead of the competition. Refinements large and small were ongoing. A telephone system and elevator were installed around 1907. Other innovations included a dark room for amateur photographers, cinema evenings, roller skating parties in the Dining Room and lawn tennis in the gardens. The private jinrikisha (two-wheeled carriages pulled by human labour) were replaced by a motor garage with a fleet of passenger cars for hire.

Behind the scenes, the kitchens were frequently upgraded with the latest in culinary technology. Raffles even had its own slaughterhouse, located away from the hotel, and, briefly, a dairy farm. Travellers noticed: “Raffles is one of the oldest and yet one of the most modern hotels in Singapore, for every effort is made to keep pace in all directions in the matter of building fixtures, appliances,” praised a writer in 1917.

Tigran Sarkies did not live to read that praise. He set sail for England in November 1910 and two years later Singapore papers carried news of his death at St Leonard’s-on-Sea in Sussex, England. He was 51. His obituary noted that he had been ill for some time so his death was not unexpected. The business of Sarkies Brothers, Hotel Proprietors, however, continued without interruption.

Aviet, now senior partner, continued to oversee Raffles from Rangoon and left the day-to-day affairs to others. Two fellow Armenians now played key roles: Joe Constantine, manager from 1903 to 1915, and Martyrose Sarkies Arathoon who joined as an accountant in 1906 and was made partner in the Sarkies Brothers business in 1918, when he essentially took charge.

The 1920s was, on the whole, a splendid decade for Raffles. The opening of the ballroom in January 1921 was timed perfectly to usher in the “roaring twenties” with an in-house band and nightly dancing. Large groups of tourists now regularly visited Singapore on round-the-world cruises. In 1925 alone, Raffles made arrangements to entertain some 3,000 tourists from six different ships. Evenings took the form of an elegant cruise dinner and dance laid out in the spacious ballroom. When it was realised that the hotel’s best cutlery was being pocketed as souvenirs, inexpensive pieces were substituted.

The ballroom of Raffles Hotel opened in 1921 and was reputed to be the largest hotel ballroom in the east at the time. Courtesy of Raffles Singapore.

The ballroom of Raffles Hotel opened in 1921 and was reputed to be the largest hotel ballroom in the east at the time. Courtesy of Raffles Singapore. (From left) Jacob Constantine (manager), Arshak Sarkies (founder and owner), Martin Sarkies (founder and owner) and Martyrose Arathoon (accountant) of the Raffles Hotel, 1906. Image reproduced from Nadia H. Wright, The Armenians of Singapore: A Short History (George Town, Penang: Entrepot Publishing, 2019), 86. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 305.89199205957 WRI).

(From left) Jacob Constantine (manager), Arshak Sarkies (founder and owner), Martin Sarkies (founder and owner) and Martyrose Arathoon (accountant) of the Raffles Hotel, 1906. Image reproduced from Nadia H. Wright, The Armenians of Singapore: A Short History (George Town, Penang: Entrepot Publishing, 2019), 86. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 305.89199205957 WRI). The New Year’s Eve Fancy Dress Ball held at Raffles Hotel was the highlight of Singapore’s social calendar until World War II. This photograph was taken in 1934. Courtesy of Raffles Singapore.

The New Year’s Eve Fancy Dress Ball held at Raffles Hotel was the highlight of Singapore’s social calendar until World War II. This photograph was taken in 1934. Courtesy of Raffles Singapore.Raffles Falls on Hard Times

In the early 1930s, all of Singapore’s hotels fell on hard times as the effects of the great economic depression seeped into every corner of the globe. The tourist trade shrank and the spending power of the resident European population diminished. The stress was more than the remaining Sarkies brother could bear. On 9 January 1931, Arshak died in Penang at the age of 62. The newspapers paid tribute to a generous man “who had earned the regard of all who met him”. Arshak was thus spared the terrible misfortunes that subsequently threatened the hotel’s existence.

Four months after Arshak’s death, John Little Department Store took Raffles Hotel to court for debts amounting to $36,796. It was soon disclosed that the firm of Sarkies Brothers had liabilities totaling over $3.5 million! The subsequent inquiry revealed the firm’s cash reserves had been strained by substantial payments made to Aviet’s widow to buy out her husband’s 40 percent share in Sarkies Brothers. Then there were hefty loans, mainly from the Chartered Bank, the largest creditor, which had been taken out to upgrade two other Sarkies hotels – the Sea View in Singapore and the E&O Hotel in Penang. The main drain was the E&O, which Arshak had lavishly rebuilt in 1928. Construction costs had skyrocketed and this, combined with the loss of revenue during the rebuilding, as well as a general decline in business upon completion, spelt disaster.

Although the Raffles remained profitable, there was no ready cash for wages and provisions, and there was a real danger that it would close. Fortunately, the creditors agreed for Sarkies Brothers, Hotel Proprietors to be placed in the hands of the official receiver and discussions on how to keep the hotel afloat began. Although business continued as usual, it proved “a most intricate bankruptcy” involving a tangled web of conflicting interests, 195 creditors and a host of complicated issues.

After two years of negotiations, all parties finally reached an agreement. On 28 February 1933, a new company, Raffles Hotel Limited, was incorporated to take over Raffles. (A separate, similar company was set up to take over the E&O.) When plans for Raffles’ future were unveiled, the official handling the case confirmed his faith in the hotel and asked the new shareholders to do the same, saying, “I can only put it to you this way, that the measure of your faith in the shares which you hold in Raffles Hotel must be the measure of your faith in the colony”.

No Singapore hotel survived this difficult time unscathed. The Adelphi Hotel on Coleman Street was placed in receivership. Hotel van Wijk along Stamford Road, home to Dutch travellers for over 30 years and famed for its curry and draught beer, closed, as did Raffles’ main rival, the Hotel de L’ Europe just opposite the Padang. Rebuilt in 1907 with 120 rooms, an imposing dining room and 300 employees, the L’ Europe was the Raffles’ closest competitor. By 1932, the L’ Europe could no longer withstand the competing pressures of poor business and an obligation by the terms of its lease to rebuild the hotel. In 1934, the government acquired the site for the new Supreme Court building.

A Hotel for All Times

The many guests who arrived during the 1920s and 1930s were largely oblivious to these fluctuations in the hotel’s fortunes. Important guests such as the Prince of Wales; playwright, actor and singer, Noel Coward; and actor and director, Douglas Fairbanks and actress, Mary Pickford, who were followed to the ballroom by fans seeking autographs, added lustre to the hotel’s reputation.

Charlie Chaplin and his brother Syd visited in 1932 and were photographed in the dining room by M.S. Nakajima, a Japanese photographer whose Bras Basah wing studio was frequented by the elite. Among the writers who visited, no one is more associated with this era than Somerset Maugham. His numerous visits to Singapore and Malaya in the 1920s and early 1930s resulted in two volumes of short stories, The Casuarina Tree and Ah King as well as a play, The Letter. When The Casuarina Tree was published in 1926, Maugham explained the meaning of the title – the casuarina is a grey, rugged tree found along tropical coasts that appears a bit grim beside the lush vegetation about it, thus suggesting exiled Europeans who in temperament and stamina are often ill-equipped for life in the tropics.

By the mid-1930s, Raffles’ fortunes were back on the mend. People resumed travelling and, with the L’ Europe closed, Raffles emerged as the undisputed social centre. The hotel also benefitted from the sharp increase in the military services population – the British Army and Royal Air Force had swelled the ranks of the European community and more were expected with the completion of the new naval base in Sembawang.

Although still ranked as one of the best hotels in the East, one visitor observed, not without fondness, that Raffles was “cherished rather for its Somerset Maugham associations than for the distinction of its décor”. The management responded by bestowing a new title on Raffles – “the historic hotel of Singapore”. And so it was called on hotel stationery and in advertisements. In the eyes of many, Raffles was no longer just a hotel but a meeting place of world travellers, an attraction in its own right that once visited could be added to the list of sights seen and extolled. It had become an icon that was perceived to be romantic and exotic in travel and a symbol of the fables of the East – immortalised by writers, patronised by all.

With this we come to the end of the story of Raffles Hotel’s early heyday – but not the end of the Raffles story. On 16 February 1942, Raffles was taken over by the invading Japanese forces and renamed Syonan Ryokan – Light of the South Hotel, and after the Japanese exited in August 1945, it was briefly occupied by the Allied forces. But the hotel emerged from the war relatively unscathed. “Like a dowager at the end of a long night, she showed a touch of genteel shabbiness but no real scars”, recalled the Australian journalist Harry Gordon in 1946.

The 1950s were a happy decade. Raffles remained the haunt of the well-to-do and well-known. Buoyant conditions financed a much-needed facelift with suites and public areas modernised and airconditioning installed. For some visitors the patina of age took on negative connotations. Oswald Wynd, in his novel Moon of the Tiger published in 1958, described Raffles as “alien to the time, a hangover from something that really no longer existed. Even the (war) hadn’t altered the tone permanently; it had returned to being something colonial, cool and pillared, once again consecrated to the doings of the Tuans and Mems who, as a species, were doomed”.

In the 1960s, competition came from the international hotels making their appearance on Orchard Road. The first was the Hotel Singapura Intercontinental, which opened in 1963 with an American-style coffee shop and 195 rooms. As the Singapore skyline changed, the old Raffles seemed increasingly out of step with changing times, appreciated for its historic associations rather than the style of its rooms. Eventually no amount of nostalgia could smooth over the problems inherent in the antiquated buildings.

For a time the very existence of the hotel seemed threatened, but fortunately a sense of history and heritage prevailed. In 1987, its centenary year, the Raffles Hotel was declared a national monument, thus ensuring its survival and the integrity of its tropical gardens and architecture. Two years later a complete restoration and redevelopment inspired by the hotel’s early heyday took place. When the new Raffles reopened on 16 September 1991, revellers raised their glasses and toasted to the Grand Old Dame’s next century.

The Legacy of Syed Mohamed Alsagoff

One of the key reasons why Raffles Hotel was able to survive its near closure in 1931 was the existence of a long-term lease on the land and buildings which the hotel occupied. There is an unusual story behind it. As we have seen, Raffles Hotel had opened at No 1 Beach Road, in December 1887. Its success enabled expansion into two adjacent parcels – No 3 Beach Road (Palm Court wing) and along Bras Basah Road. No 3 Beach Road was leased from the Seah family and in 1907 Tigran and Aviet Sarkies purchased the land for $125,064.

Unfortunately, they could never hope to purchase the other two parcels because they were part of the estate of Syed Ahmed Alsagoff (d. 1875), a wealthy Arab trader who had left a large estate with many properties to his widow and children. In his will, he appointed his son Syed Mohamed Alsagoff (d. 1906) as executor. He also stated that none of his properties could be sold until 20 years after the death of his last surviving child (which did not occur until 1961) so the Sarkies knew they could never hope to own the main properties in which they carried out their hotel business.

The lease signed in 1887 was renewed periodically. Significantly, the hotel was able to secure a generous 70-year lease on good terms from the Alsagoff estate effective from 1 January 1926. Thus, when the new company of Raffles Hotel Limited was formed in 1933, the remainder of this long lease was its most important asset.

It must be noted that Syed Mohamed was an outstanding landlord. He funded most of the early building projects and it is his name that appears on most of the original Raffles Hotel building plans that survive in the National Archives, Singapore.

Gretchen Liu is a former journalist and book editor as well as the author of several illustrated books, including Pastel Portraits: Singapore’s Architectural Heritage and Singapore: A Pictorial History. As the former curator of the Raffles Hotel Collection, she oversaw all of the heritage projects during the hotel’s 1989–1992 restoration and for some years after that.

REFERENCES

Newspapers and Periodicals

Where shall we stay: The hotels and resthouses of Malaya. (1936). The Straits Times Annual.

The sphere, orient number. (1936, November 28).

Various Raffles Hotel brochures circa 1900–1950s.

Guidebooks

Bradshaws’ through routes, overland guide and handbook to India, Egypt, Turkey, Persia, China, Australia and New Zealand. (1890). London: W.J. Adams & Sons. (Bradshaw’s guide office). (Not available in NLB holdings)

Handbook for travellers to Singapore. (1920). Singapore: Far east Tourist Agency. Retrieved from Roots.sg website. Books

Borland, B. (1933). Passports for Asia. New York: Long & Smith Inc. (Call no.: R 950 BOR)

Brown, E.A. [1935]. Indiscreet memories. London: Kelly & Walsh. (Call no. RCLOS 959.51 BRO-[RFL])

Calder, R. (1989). Wilie: The life of Somerset Maugham. London; Heinemann. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Cameron, C. (1880). Wanderings in South-Eastern seas. London: T, Fisher Unwin Ltd.

Chaplin, C. (1964). My autobiography. London: The Bodley Head. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Coward, N. (1937). Present indicative. New York: Doubleday, Doran and Company. (Call no.: RRARE 882.912 COW; Accession no.: B29268862J)

Curle, R. (1923). Into the east: Notes on Burma and Malaya. London: Macmillan and Co. (Call no.: RCLOS 915.95 CUR-[RFL])

Kipling, R. (1900). From sea to sea, and other sketches: Letters of travel (Vol. 1). London: Macmillan and Co. (Call no.: RRARE 915.4 KIP; Accession no.: B29032482H [v.1])

Lockhart, R.H.B. (1921). Return to Malaya. London: Putnam. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.5 LOC-[ET])

Maugham, W.S. (1926). The casuarina tree. London: Heinemann. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Macmillan, A. (1925). Seaports of the Far East: Historical and descriptive, commercial and industrial facts, figures, & resources. London: W. H. & L. Collingridge. (Call no.: RCLOS 387.12095 SEA)

Morley, S. (1969). A talent to amuse: A biography of Noel Cowar. Boston: Little Brown and Company. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Morris, I.J. (1958). My east was gorgeous. London: The Travel Book Club. (Call no.: RCLOS 915.9 MOR)

Morrison, I. (1942). Malayan postscript. London: Faber. (Call no.: RCLOS 940.53595 MOR)

Perkins, C.B. (1909). Travels from the Grandeurs of the west to the mysteries of the east or from occident to orient and around the world. San Francisco, Calif.: C. B. Perkins Co. (Call no, RCLOS 910.4 PER)

Plate, A.G. (1906). A cruise through eastern seas, being a travellers’ guide to the principal objects of interest in the Far East. London: Llyod Bremen. (Call no.: RRARE 915 PLA; Microfilm no.: NL26040)

Rennie, J.S.M. (1933). Musings of J.S.M.R., mostly Malayan. Singapore: Malaya Pub. House. (Call no.: RRARE 959.5 REN; Microfilm no.: NL8447)

Turnbull, C.M. (1977). A history of Singapore, 1819–1975. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 TUR-[HIS])

Wright, A., & Cartwright, H.A. (1908). Twentieth century impressions of British Malaya: Its history, people, commerce, industries and resources. London: Llyod’s Greater Britain Pub. (Call no.: RRARE 959.52033 TWE; Microfilm no.: NL16084)

Wright, N.H. (2003). Respected citizens: The history of Armenians in Singapore and Malaysia. Middle Park, Vic.: Amassia Publishing. (Call no.: RSING 305.891992 WRI)

Wynd, O. (1958). Moon of the tiger. London: Cassell. (Call no.: RCLOS 823.914 WYN-[RFL]))