Singapore Through the Eyes of 19th century Westerners

Nor Afidah Abd Rahman shares how the impressions the first Western travellers held of colonial Singapore were influenced by their preconceived perceptions of the exotic East.

This scene stretches from Pearl’s Hill on the left to Tanjong Rhu on the right. In the centre is Government Hill (now Fort Canning). Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

This scene stretches from Pearl’s Hill on the left to Tanjong Rhu on the right. In the centre is Government Hill (now Fort Canning). Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.From the mid-18th century onwards, Western powers enthusiastically explored the “mysterious” East through military, scientific and commercial missions. Under the flags of different imperial sponsors, the underlying aim of these expeditions was to outdo each other through the accumulation of first-hand knowledge. The broad quest for local knowledge dictated the assembly of experts; in one expedition for example “there was a naturalist, conchologist, mineralogist, botanist, horticulturalist and draughtsmen”.1 Their investigations were shared in travel accounts that fit into the standard narrative of scientific exploration.2 Steam technology-empowered mass travel and the mid-19th century saw more independent travellers exploring the East.3 These travel writers stressed the experience of travel itself over methodical reporting of the lands visited. Unfortunately, these accounts, while still informative, have been coloured by the “meditations, reflection and reverie” of the Western traveller.4

Singapore was a natural stopover for ships because of its location at the crossroad of major East-West trade routes.5 Steam travel elevated Singapore from port-of-call to the coal-hole of the East. Ships criss-crossing the globe would transit at the Singapore harbour to refuel before continuing to their next stop.6 Passengers used this respite from the sea journey to satisfy their curiosity about Singapore and recorded these encounters in their travel diaries or journals.

The Tamed Jungle…

Observations by Western travellers stimulated ideas about Singapore that endeared this faraway British settlement to the West. They fed the European market’s curiosity about exotic locations, depicting lush scenes of native lands and a nascent colony on the other side of the world.7 The quick jottings and candid musings about Singapore did not disappoint as these accounts frequently praised the colony’s progress. The perception of Singapore as an inhabitable jungle swarming with bandits was the predominant theme, while the taming of the island into a flourishing port under the British barely hid the gushing approval for imperial rule:

“I remained lost in the thoughts aroused in me by the unexpected sight of the commercial achievement of the English. On this shore where not 20 years ago were grouped a few wretched Malay villages, half fishermen, half pirates, where virgin forest extended to the seashore, where the tiger hidden in the jungle awaited his prey, where a pirate canoe scarcely disturbed an empty sea, has risen today to a huge town, bustling with an industrious population…safe from the tigers which have fled into the depths of the jungle as from the bandits who are kept in check by the vigilant eyes of a tireless police; and this hospitable shore has become the centre for ships of all nations.”

–Jules Itier, Head of French commercial mission to China and the Indies, 1843–468

The theme of imperial benevolence is also detectable in the visual records of 19th-century Singapore. The historical value of these pictures notwithstanding, the pick of settings and objects fulfils the Western notion of what was picture-worthy and constitutes arguably “a form of visual propaganda”.9 Visions of progress in early 19th-century paintings of Singapore were usually angled from harbours and hills.10 The choice was practical for their panoramic sweep of the bustling town. The harbour at the Singapore River echoed Raffles’ prophecy that Singapore would be an Emporium in Imperio,11 reflected in artists’ sketches of busy clusters of ships and neat rows of warehouses from the harbour.12 Singapore’s prosperity was also calibrated from an aerial view, with artists perching themselves on vantage positions from Government Hill, Pearl’s Hill, Prinsep Hill, Mount Wallich and Mount Palmer, to document the landscapes below. The bird-eye’s treatment “strategically omitted any traces of the mangrove swamps that dotted the landscape”,13 and canvassed mainly elements that portrayed Singapore as a picturesque pseudo-European14 settlement in the East.

Both harbour and hill are found in many paintings of Charles Dyce (1816–1853),15 a 19th-century amateur painter. The twin reference points are also a signature of Dyce’s contemporary, John Turnbull Thomson (1821–1884).16 Their artwork joins the body of paintings and literature that represent the typical 19th-century Singapore construct of a little Eastern oddity made good.17

The Tamed Jungle of Untapped Spoils…

The notion of a well-governed tropical colony in the East teased the Western audience with Singapore’s economic potential. This is synchronous with the 19th-century explorers’ depiction of the tropics as lands of great abundance and fertility.18 The founding of Singapore fanned the agriculture dream that a British spice powerhouse in the East was in the making.19 Raffles kickstarted the campaign for large-scale agriculture with his Botanical Gardens project in 1822,20 hoping it would catch on and transform Singapore’s jungles into thriving plantation estates. The thick and impenetrable jungles that the British inherited evoked astonishingly “rich and sensual responses” from travellers brave enough to wander into them. Their portrayals pandered to the romantic notion of an idyllic countryside that was disappearing in the West due to rapid industrialisation. Nostalgia for the countryside found its way into their wondrous renditions of Singapore’s interior:21

“Reverting to the glimpse of the jungle which the pencil of the artist has afforded us we perceive how very beautiful are the forms which Nature assumes in those regions. The wealth of the vegetable kingdom there is endless…Everywhere, a luxuriant and hardy under-growth, and endless families of creepers, occupy the spaces between the trees, and present to the eye a sea of undulating blossoms, of brilliant hues and overpowering fragrance, or shoot aloft trunk and branches, and stretch in festoons, or depend like lamps of infinitely brilliant flowers.”

–Captain Charles Bethune, from an 1840 China expedition22

The tropical diversity and overpowering greenery23 fuelled the promise of agriculture, muting the darker reality that the jungles were hosts to tropical diseases and other perils. Early colony residents found these dangers real enough to stay away, with many preferring to pursue gains from trade “to the exclusion of her agriculture”.24 Extending the economic frontier from the town limits to the wild interiors had few takers as jungle-clearing and nurturing crops were a herculean task plagued by high outlays and slow payouts. Regardless, travel writers peddled their faith in the virgin soil, encouraging Europeans to fill the enterprise void left behind by the original inhabitants:25

“The energy of the European character… would turn the tables, as it were, upon Nature – pierce her solitudes, hev down her forests, and render those incalculable powers of the Earth, which hitherto run to waste, subservient to the purposes of human life.”

–Captain Charles Bethune, from an 1840 China expedition26

The Tamed Jungle of Untapped Spoils and Curious Races…

The Western travellers’ senses frequently turned to the natives of Singapore. The different races, each with its own unique colour27 and sound,28 formed a heady mix:

“The city is ablaze with color and motley with costume.. Every Oriental costume from the Levant to China floats through the streets–robes of silk, satin, brocade, and white muslin,…Parsees in spotless white, Jews and Arabs in dark rich silks; Klings in Turkey red and white; Bombay merchants in great white turbans…Malays in red sarongs, Sikhs in pure white Madras muslin…; and Chinamen of all classes, from the coolie in his blue or brown cotton, to the wealthy merchant in his frothy silk crepe and rich brocade…”

–Isabella Bird, author of The Golden Chersonese and the Way Thither, 187929

The townsfolk perpetuated the common perception that the East was peopled by exotic races, an idea that influenced the photographic treatment of Singapore during the photography boom of the 1880s and 1890s.30 The natives’ outlandish attire, movements and other habits set them apart from the Europeans and created the racial divide expected of a colonial society. Implicit in accounts that paint the native races in this light is the lofty position of the Europeans within that stratified society.31 The distinction gets sharper when the toiling working class (locals waving the punkah fans, carrying the umbrella, preparing saddles, driving gharries, bearing torches) or else their wretched living spaces featured side-by-side with the well-off Europeans who passed their days in leisure and dinner parties:32

“The native portion of the city is entirely separate from the foreign portion. The Malays live in small, poorly-built huts and houses, each house containing many people. The native portion is very closely-built and densely-populated, but the English officials succeed in making the natives keep the houses and streets comparatively clean. Europeans in Singapore manage to get about as much ease and pleasure out of life as is possible, and yet at the same time to make as much money as possible. Servants are so cheap that every foreigner has two or three to attend to his every want…The usual method of entertaining is by giving dinners.”

–E.W. Eberle, Lieutenant, United States Navy, taken from The Washington Post, 189233

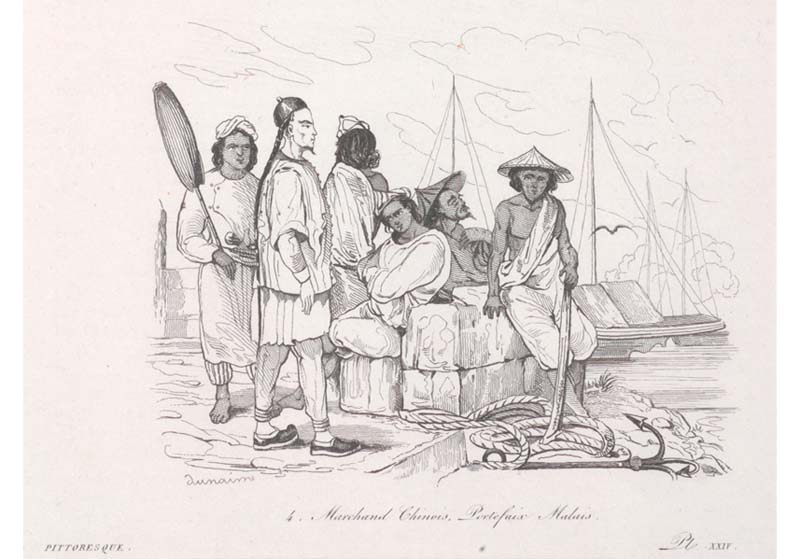

An engraving of the port of Singapore entitled “Chinese Merchant, Malay Porter” by the official artist of the corvette L’Astrolabe and published in the Voyage pittoresque autour du monde in 1834. Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore, Singapore Heritage Board.

An engraving of the port of Singapore entitled “Chinese Merchant, Malay Porter” by the official artist of the corvette L’Astrolabe and published in the Voyage pittoresque autour du monde in 1834. Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore, Singapore Heritage Board.The Tamed Jungle of Untapped Spoils and Curious Races Revisited

Nineteenth-century travel accounts of Singapore generally celebrated the civilising effect of imperial rule. There were, however, observations that recorded some of its casualties:

“But in this part of the world [Singapore], the word palanquin is applied to a kind of long chest, placed on four wheels…A courier, called a says, [syce] holds the head of the horse to direct its movements, and excite it to speed. These men are generally either miserable Bengalese or the very poorest of the Malays, and a painful sight it is to see these poor fellows who are usually emaciated, debilitated by poverty and wretchedness, running about for hours together, until they are weary and breathless. Their costume is of the simple kind; their feet and legs are naked, their chests uncovered, and their hair is concealed under a cotton handkerchief rolled like a turban round the head: the only garment they wear is a pair of drawers, fastened round the waist and descending no further than the knees.”

–Yvan, Melchior, a French physician in Singapore34

Sober reflections on the abject poverty of the working class35 shatter the perception that an all-round wholesome development was taking shape and beg to examine the natives beyond their peculiar traits. The bounty that lay hidden in the fertile soil was also a story shy of a happy ending. The nutmeg disaster of the 1850s and 1860s shattered the British spice dream and left many European planters in Singapore ruined:36

“The soil is generally very inferior, its disposition and the climate diminish the number of valuable staples capable of being advantageously cultivated… The cultivation of coffee, sugar and nutmegs has been tried largely but at a lavish and hitherto vain expenditure.”37

Singapore was indeed a picture of progress on the eve of the 20th century. Yet its success story unfolds in more nuanced plots than the themes found in the writings of many early Western travellers. Colonial literary and visual images produced by travellers were very much a product of Western cultural and aesthetic expectations of the East. In living up to these expectations, Western visitors to Singapore were likely to see the country more as an aesthetic construct rather than as an evolving habitat and society filled with real people.38

Nor Afidah Abd Rahman is a Senior Librarian with the National Library of Singapore.

REFERENCES

Books

Bennett, G. (1834). Wanderings in New South Wates, Batavia, Pedir Coast, Singapore, and China (Vol. 2). London: R. Bentley. Retrieved from BookSG. (Call no.: RRARE 910.4 BEN; Microfilm no.: NL7979; Accession no.: B29034264H [v. 2])

Bird, I.L. (2013). The Golden Chersonese and the way thither (Vol. 2). [ebook]. London: Forgotten Book. (Original work published 1883).

Cameron, J. (1865). Our tropical possessions in Malayan India: Being a descriptive account of Singapore, Penang, Province Wesley, and Malacca; their peoples, products, commerce, and government. London: Smith, Elder and Co. Retrieved from BookSG. (Call no.: RRARE 959.5 CAM-[JSB]; Microfilm no.: NL11224; Accession no.: B29032445G)

Davidson, G.F. (2008, October 24). Trade and travel in the Far East or recollections of twenty-one years passed in Java, Singapore, Australia and China [ebook]. Retrieved 2014, July, from archive.org.

Driver, F., & Martins, L. (Eds.). (2010). Tropical vision in an age of empire (pp. 3–5). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Retrieved from ProQuest ebray.

Falconer, J. (1987). A vision of the past: A history of early photography in Singapore and Malaya. The photographs of G.R. Lambert & Co., 1880–1910. Singapore: Times Editions. (Call no.: RCLOS 779.995957 FAL)

Goh, C.B. (2013). Technology and entrepot colonialism in Singapore, 1819–1940 (p. 145). Singapore: ISEAS. (Call no.: RSING 338.06409595 GOH)

Hall-Jones, J. & Hooi, C. (1979). An early surveyor in Singapore: John Turnbull Thomson in Singapore 1841–1843 (pp. 1, 24, 31–34). Singapore: The National Museum. (Call no.: RSING 925 THO)

Hawks, F.L. (1856). The narrative of the expedition of an American squadron to the China seas and Japan, performed in the years 1852, 1853, and 1854, under the command of M.C. Perry, United States Navy… (Vol. 1). Washington: Beverly Tucker. Retrieved from Internet Archive website.

Lim, I. (2003). Sketches in the Straits: Nineteenth-century watercolours and manuscript of Singapore, Malacca, Penang and Batavia by Charles Dyce. Singapore: NUS Museum. (Call no.: RSING 759.2911 LIM)

Liu, G. (Ed.). (1987). Nineteenth century prints of Singapore (p. 7). Singapore: National Museum. (Call no.: RSING 769.4995957 TEO)

Makepeace, W., Brooke, G.E., & Braddell, R.St.J. (Eds.). (1991). One hundred years of Singapore (Vol. 2). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 ONE)

Singh, A.R. (1995). A journey through Singapore: Travellers’ impressions of a by-gone time. Singapore: Landmark Books. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 REE)

Wise, M., & Wise, M. H. (1996). Travellers tales of Singapore. Brighton: In Print Publishing. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 TRA).

Wong, H.S., & Waterson, R. (2010). Singapore through 19th century prints & paintings. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet and National Museum of Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 769.499595703 WON)

Worsfold, W.B. (1893). A visit to Java, with an account of the founding of Singapore (pp. 280–281). London: Richard Bentley and Son. Retrieved from Project Gutenberg website.

Yvan, M. (1855). Six months among the Malays and a year in China. London: J. Blackwood. (Call no.: RRARE 959.5 YVA; Microfilm no.: NL7610)

Articles

A lady on Singapore. (1892, October 5). Straits Times Weekly, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Arnold, D. (2000, March). “Illusory riches”: Representations of the tropical world, 1840–1950. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, 21 (1), 6–8. Retrieved from EBSCOHost Academic Search Premier

Driver, F. (2004). Distance and disturbance: Travel, exploration and knowledge in the nineteenth century. Transactions of the Royal Historical Society (sixth series), 14, 73–92. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Dupree, A.H. (1953). Science vs. the military: Dr. James Morrow and the Perry expedition. Pacific Historical Review, 22 (1), 29–31. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Han, M.L. (2003, October). From travelogues to guidebooks: Imagining colonial Singapore; 1819–1940. Sojourn: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia, 18 (2), 257–278. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Mazower, M. (2002). Travellers and the Oriental city, c. 1840–1920. Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 12, 59–111. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Notes in the Straits. (1843, September 7). The Singapore Free Press, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Oddities of Singapore. (1892, August 2). Straits Times Weekly, p. 462. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Ramsland, M. (2010). Impressions of a young French gentleman’s 1866 visit to the Australian colonies. Australian Studies, 2. Retrieved from National Library of Australia website.

Singapore street scenes. (1893, May 31). Straits Times Weekly, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

The diseased and indigent of Singapore, their miseries and the means for their relief. (1845, September 23). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Untitled. (1844, December 5). The Singapore Free Press, p. 2 Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Wikipedia. (2014, August). Tropical geography. Retrieved from Wikipedia.

NOTES

-

Liu, G. (Ed.). (1987). Nineteenth century prints of Singapore (p. 7). Singapore: National Museum. (Call no.: RSING 769.4995957 TEO); Dupree, A.H. (1953). Science vs. the military: Dr. James Morrow and the Perry expedition. Pacific Historical Review, 22 (1), 29–31. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website; Ramsland, M. (2010). Impressions of a young French gentleman’s 1866 visit to the Australian colonies. Australian Studies, 2, 1–2. Retrieved from National Library of Australia website. ↩

-

Driver, F. (2004). Distance and disturbance: Travel, exploration and knowledge in the nineteenth century. Transactions of the Royal Historical Society (sixth series), 14, 73–92, pp. 78, 80–85. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Wong, H.S., & Waterson, R. (2010). Singapore through 19th century prints & paintings (p. 11). Singapore: Editions Didier Millet and National Museum of Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 769.499595703 WON) ↩

-

Mazower, M. (2002). Travellers and the Oriental city, c. 1840–1920. Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 12, 59–111, p. 60. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Wong & Waterson, 2010, p. 11. ↩

-

Hawks, F.L. (1856). The narrative of the expedition of an American squadron to the China seas and Japan, performed in the years 1852, 1853, and 1854, under the command of M.C. Perry, United States Navy… (Vol. 1; p. 129). Washington: Beverly Tucker. Retrieved from Internet Archive website. ↩

-

Lim, I. (2003). Sketches in the Straits: Nineteenth-century watercolours and manuscript of Singapore, Malacca, Penang and Batavia by Charles Dyce (pp. 15, 32). Singapore: NUS Museum. (Call no.: RSING 759.2911 LIM) ↩

-

Falconer, J. (1987). A vision of the past: A history of early photography in Singapore and Malaya. The photographs of G.R. Lambert & Co., 1880–1910 (p. 10). Singapore: Times Editions. (Call no.: RCLOS 779.995957 FAL) ↩

-

Wise, M., & Wise, M. H. (1996). Travellers tales of Singapore (p. 3). Brighton: In Print Publishing. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 TRA). Description of Singapore as an international “commercial mart” also found in Hawks, 1856, p. 125. ↩

-

Wong & Waterson, 2010, p. 146. ↩

-

Wong & Waterson, 2010, p. 87. ↩

-

Wong & Waterson, 2010, p. 87. ↩

-

Hall-Jones, J. & Hooi, C. (1979). An early surveyor in Singapore: John Turnbull Thomson in Singapore 1841–1843 (pp. 1, 24, 31–34). Singapore: The National Museum. (Call no.: RSING 925 THO) ↩

-

Bennett, G. (1834). Wanderings in New South Wates, Batavia, Pedir Coast, Singapore, and China (Vol. II; pp. 129–130). London: R. Bentley. Retrieved from BookSG. (Call no.: RRARE 910.4 BEN; Microfilm no.: NL7979; Accession no.: B29034264H [v. 2]) ↩

-

Arnold, D. (2000, March). “Illusory riches”: Representations of the tropical world, 1840–1950. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, 21 (1), 6–8. Retrieved from EBSCOHost via NLB’s eResources website; Wikipedia. (2014, August). Tropical geography. Retrieved from Wikipedia. ↩

-

Makepeace, W., Brooke, G.E., & Braddell, R.St.J. (Eds.). (1991). One hundred years of Singapore (Vol. 2; p. 29). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 ONE); Goh, C.B. (2013). Technology and entrepot colonialism in Singapore, 1819–1940 (p. 145). Singapore: ISEAS. (Call no.: RSING 338.06409595 GOH); Driver, F., & Martins, L. (Eds.). (2010). Tropical vision in an age of empire (p. 14). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ↩

-

Wong & Waterson, 2010, p. 139. ↩

-

Wong & Waterson, 2010, p. 139. ↩

-

Davidson, G.F. (2008, October 24). Trade and travel in the Far East or recollections of twenty-one years passed in Java, Singapore, Australia and China [ebook] (p. 26). Retrieved 2014, July, from archive.org. ↩

-

Bennett, 1834, pp. 177–178; Untitled. (1844, December 5). The Singapore Free Press, p. 2 Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Driver & Martins, 2010, p. 14. ↩

-

Wong & Waterson, 2010, p. 146. ↩

-

Foenander, T. (n.d.). Raphael Semmes’ description of early Singapore. Retrieved from The Navy & Marine Living History Association website. ↩

-

Bird, I.L. (2013). The Golden Chersonese and the way thither [ebook] (pp. 150–151). (Vol. 11; pp. 167–168). London: Forgotten Book. (Original work published 1883). ↩

-

Bird, 2013, pp. 144–145. ↩

-

Falconer, 1987, pp. 30–31; Jackson, A. (1992). Imagining Japan: The Victorian perception and acquisition of Japanese culture. Journal of Design History 5 (4), 245–256, pp. 247–248. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Liu, 1987, pp. 12–13; Worsfold, W.B. (1893). A visit to Java, with an account of the founding of Singapore (pp. 280–281). London: Richard Bentley and Son. Retrieved from Project Gutenberg website; A lady on Singapore. (1892, October 5). Straits Times Weekly, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Oddities of Singapore. (1892, August 2). Straits Times Weekly, p. 462. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Yvan, M. (1855). Six months among the Malays and a year in China (p. 64). London: J. Blackwood. Retrieved from catalog.hathitrust.org. (Call no.: RRARE 959.5 YVA; Accession no.: B29032526G) ↩

-

Yvan, 1855, pp. 71–73, 81, 101–102; The diseased and indigent of Singapore, their miseries and the means for their relief. (1845, September 23). The Straits Times, p. 3; Singapore street scenes. (1893, May 31). Straits Times Weekly, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Han, M.L. (2003, October). From travelogues to guidebooks: Imagining colonial Singapore, 1819–1940. Sojourn: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia, 18 (2), 257–278, pp. 264–265. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website; Singh, A.R. (1995). A journey through Singapore: Travellers’ impressions of a by-gone time (p. 44). Singapore: Landmark Books. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 REE) ↩

-

Cameron, J. (1865). Our tropical possessions in Malayan India: Being a descriptive account of Singapore, Penang, Province Wesley, and Malacca; their peoples, products, commerce, and government (p. 82). London: Smith, Elder and Co. Retrieved from BookSG. (Call no.: RRARE 959.5 CAM-[JSB]; Microfilm no.: NL11224; Accession no.: B29032445G) ↩

-

Notes in the Straits. (1843, September 7). The Singapore Free Press, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Mazower, 2002, p. 70; Driver & Martins, 2010, pp. 3–5. ↩