Darwin in Cambridge & Wallace in the Malay Archipelago

Research is still turning up new findings about the lives and science of Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace. Among other things, Dr John van Wyhe addresses the misconception that Darwin cheated Wallace of his rightful place in history.

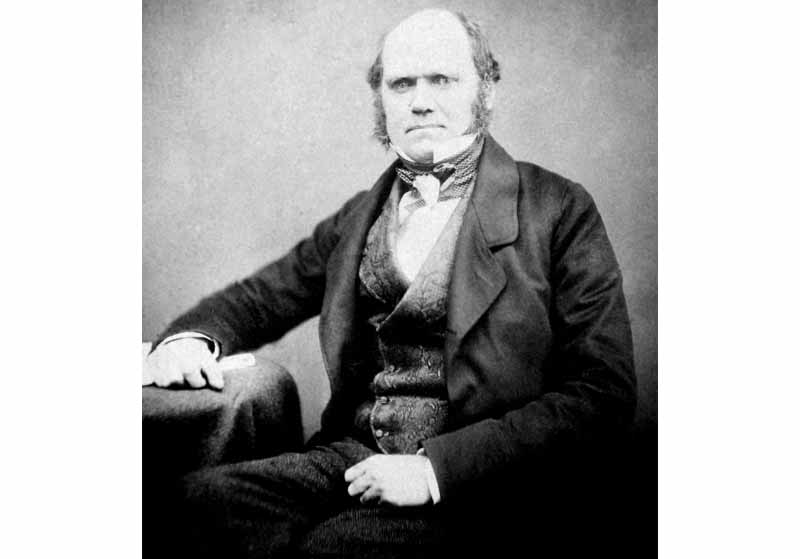

Photograph of Charles Darwin, 1854.

Photograph of Charles Darwin, 1854.

This article is based on the talk “Darwin and Wallace” given by Dr John van Wyhe as part of the National Library’s Prominent Speaker Series. Held on 31 July 2014 at the National Library Building, the talk was based on two of Dr van Wyhe’s recent books: Charles Darwin in Cambridge: The Most Joyful Years and Dispelling the Darkness: Voyage in the Malay Archipelago and the Discovery of Evolution by Wallace and Darwin.

Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace are best remembered as the co-proposers of the theory of evolution by natural selection. Now, over 150 years later, evolution is the foundation of the life sciences and more. It is no wonder that Darwin and Wallace remain some of the most important figures in the history of science. Yet, despite all that has been written about them over the years, historical research is still turning up surprising new findings about their lives, their science, and how they came to change our understanding of life on earth forever.

Many believe that Wallace has been overlooked and denied his rightful fame for his work on the theory of evolution and that Darwin had perhaps even stolen some of Wallace’s ideas and delayed the publication of Wallace’s paper in favour of his own. This is not true and is the subject of my book Dispelling the Darkness: Voyage in the Malay Archipelago and the Discovery of Evolution by Wallace and Darwin (2013).1

Charles Darwin (1809—1882) is one of the most intensely studied scientists in history, and has been for over a century. But one area of his life that has remained comparatively unexamined is his formative years as a student at the University of Cambridge. For the rest of his life Darwin held a particular affection for Cambridge. For a time he even considered a Cambridge professorship as a career. He later sent three of his sons there to be educated. Yet, the traces of what Darwin actually did and experienced as a student in Cambridge have remained undiscovered, and the details of his day-to-day life there are either largely unknown or misunderstood.

Darwin in Cambridge

Darwin entered the books as an undergraduate student at Christ’s College, Cambridge, on 15 October 1827, but as he had forgotten most of his schoolboy Greek he had to be tutored at home before entering Cambridge. (Why this mattered is explained in Darwin in Cambridge: The Most Joyful Years.2) This meant he did not arrive in Cambridge until January 1828 – and by then all the rooms in the college were filled. So he took lodgings above the tobacconist shop across the street. The owner had an arrangement with Christ’s College so that its students could rent rooms there, though this sometimes led to complaints. For instance, the shop owner across the street from the tobacconist would complain to the Master of the College that students kept knocking the hats off unwary passers-by along the street by flicking a long horsewhip from their first floor windows.

For many years it has been repeated that Darwin was a theology student at Cambridge. This is not true. There was no such undergraduate degree. Instead, Darwin was registered for an ordinary Bachelor of Arts (BA) degree. It was his intention to become a clergyman, but such training could take place only after receiving the prerequisite B.A. In the end, Darwin never undertook any divinity training.

In November 1828, Darwin moved into a set of rooms in Christ’s College, as he later recalled, “in old court, middle stair-case, on right-hand on going into court, up one flight, right-hand door and capital rooms they were.” They were indeed comfortable and recently discovered college record books reveal that Darwin’s rooms were the most expensive at €4 per quarter. The record books also reveal that his college bills over three years amounted to about €700. This was a princely sum of money at the time.

One of the more surprising findings about Darwin’s daily life as a student was the mandatory attendance at the College Chapel. This in itself is no surprise, but what was previously unknown is that Darwin almost certainly took his turn at the medieval brass lectern and read from the Bible to the assembled members of the college. It is a striking and paradoxical image. Charles Darwin has probably been attacked more than any other scientist in history as being purportedly irreligious or worse, dangerous to religion. Although Darwin would cease to believe in Christianity shortly after his voyage on HMS Beagle (1831–36), he was never an atheist.

Like many young men of his social class, Darwin passionately dedicated to the sport of shooting birds. When he could not go shooting, he would practise his aim in his comfortable college room. He later recalled in his autobiography:

“When at Cambridge I used to practise throwing up my gun to my shoulder before a looking-glass to see that I threw it up straight. Another and better plan was to get a friend to wave about a lighted candle, and then to fire at it with a cap on the nipple, and if the aim was accurate the little puff of air would blow out the candle. The explosion of the cap caused a sharp crack, and I was told that the Tutor of the College remarked, ‘What an extraordinary thing it is, Mr Darwin seems to spend hours in cracking a horse-whip in his room, for I often hear the crack when I pass under his windows.’”3

Not very keen on his official studies, Darwin devoted himself to collecting beetles instead. He soon discovered several novel ways to procure rare and unusual specimens, and had a special cabinet made to house his collection. Darwin sent records of his captures to the well-known entomologist James Stephens who regularly published records of British entomology. These were Darwin’s first words in print. So even as an undergraduate, and in a very small way, Darwin had already begun to contribute to science.

In later life Darwin liked to sheepishly recall one of his beetling misadventures: “One day, on tearing off some old bark, I saw two rare beetles and seized one in each hand; then I saw a third and new kind, which I could not bear to lose, so that I popped the one which held in my right hand into my mouth. Alas it ejected some intensely acrid fluid, which burnt my tongue so that I was forced to spit the beetle out, which was lost, as well as the third one.”4 One certainly cannot doubt his sincerity as a collector.

Darwin’s interests in science became a lifelong passion. He read the scientific travel accounts of the great German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt and dreamed of travelling on a scientific tour of his own.

Darwin became the loyal pupil of John Stevens Henslow, a professor of botany, from whom Darwin learned a great deal about scientific method. The two became such good friends that college dons who had not met Darwin referred to him as “the man who walks with Henslow.”5 Darwin also studied other branches of natural science in his own time as the university then offered little instruction in science. He eventually learned the basics of a wide range of current fields. In 1831, he successfully completed his exam to gain his B.A. degree. Darwin later recalled, “Upon the whole, the three years I spent at Cambridge were the most joyful of my happy life.”6 It was Henslow who would shortly thereafter recommend Darwin for the post of naturalist on HMS Beagle on a voyage around the world.7 The rest, as they say, is history.

A Cambridge graduate in the 1820s sporting the latest fashion – trousers (instead of knee breeches).

A Cambridge graduate in the 1820s sporting the latest fashion – trousers (instead of knee breeches).

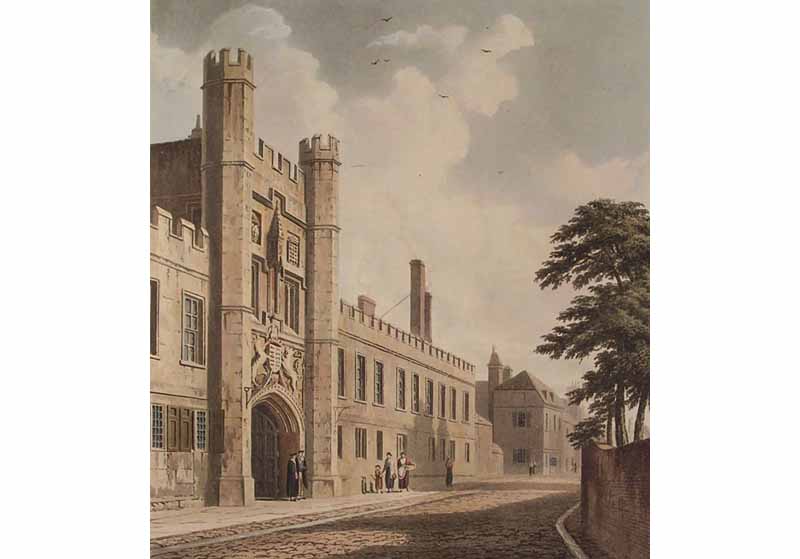

Christ's College, Cambridge, where Darwin spent his undergraduate years.

Christ's College, Cambridge, where Darwin spent his undergraduate years.

Restoration of Darwin's room at Christ's College was completed in 2009. He lived here from 1828–1831.

Restoration of Darwin's room at Christ's College was completed in 2009. He lived here from 1828–1831.

In Search of the Historical Wallace

For Alfred Russel Wallace (1823–1913) the picture is quite different. He did not come from a privileged background and although he attended a good school like Darwin’s, Wallace never went to university. His family had fallen on hard times. But as there was little science taught at universities anyway, most men of science at the time were largely self-taught. Both were middle-class, Darwin from the higher end of the spectrum, Wallace from the lower.

Darwin’s life and work have been intensively studied by historians for over a century. Wallace, on the other hand, like many other scientists of his day, has been the subject of comparatively little historical study. But unlike the thousands of other forgotten scientists of his era, Wallace has become the centre of interest of another group of people – not historians, but enthusiasts.

From the 1960s onward, articles and books about Wallace by popular writers began to appear. From one publication to another, Wallace gradually came to be portrayed as ever more “forgotten”, wronged and in need of being reinstated in the annals of history. Many popular writers have even gone so far as to suggest some nefarious skulduggery in the story of Wallace. It is now commonly suggested that Darwin or his friends treated Wallace unfairly, that he was cheated or robbed of priority or credit for his main discovery. Some writers claim that Darwin lied about when he received Wallace’s essay on evolution, or worse, even plagiarised Wallace’s work. The reason for their suspicion? In 1858, Wallace, who was living on the island of Ternate in Indonesia, mailed Darwin an outline theory that appeared remarkably similar to the one Darwin had been working on for the last 20 years. Darwin was at that time about two years away from finally completing and publishing in his so-called “big book” on evolution by natural selection.

The effect of this well-meaning posse of Wallace-championing writers and enthusiasts is striking. The public picture of Wallace has been dramatically transformed. Almost all of the main elements that are now stressed about Wallace are actually absent in accounts from his own lifetime or by those who actually knew him.

If Wallace’s name is familiar at all to the average reader today, it is usually as a supposedly forgotten underdog. Wallace? Wasn’t he the one who was cheated by Darwin? The very suggestion that a forgotten man did just as much as the famous Darwin, and ought to be just as famous, instantly awakens our sympathy. And in some people it triggers resentment against the privileged Darwin who had all the advantages in life, and now all the posthumous fame. Surely this must be unfair? But that depends on getting the facts right.

A candid investigation of the original historical sources from Wallace’s time differs strikingly from the modern picture of Wallace as the “hero-on-a-quest but cheated in the end.” Dispelling the Darkness is an attempt to reveal the historical Wallace as he lived and worked in his original time and context. Based on the most intensive research programme ever undertaken on Wallace in Southeast Asia, the real Wallace and his story turns out to be very different from the heroic version bandied about in recent years. In short, everything you have heard about Wallace is probably wrong.

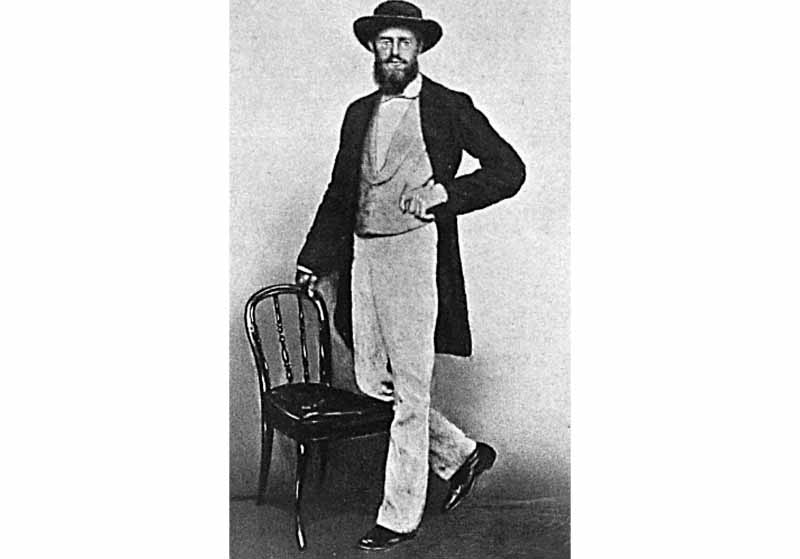

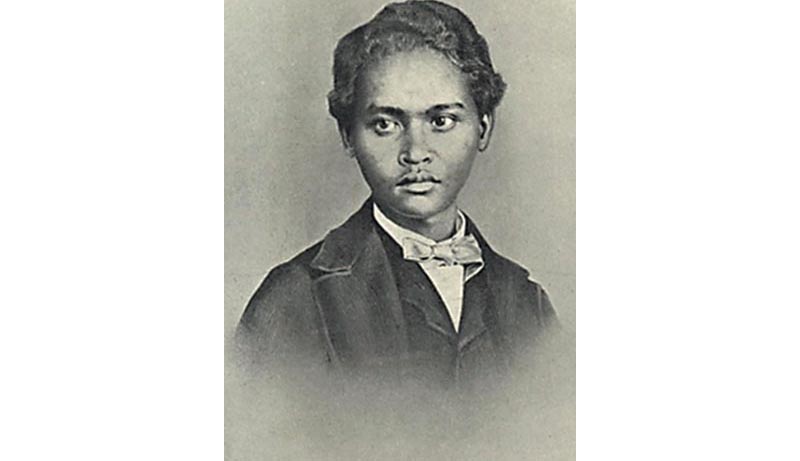

Alfred Russel Wallace in Singapore in 1862. Merchant, James ed. 1916. Alfred Ruessel Wallace Letters and Reminiscences.

Alfred Russel Wallace in Singapore in 1862. Merchant, James ed. 1916. Alfred Ruessel Wallace Letters and Reminiscences.

What Really Happened in the Archipelago?

After a series of underpaying jobs, Wallace set out for the Amazon valley in 1848 to make a living as a commercial specimen collector. (The heroic version has him going instead on a quest to solve the problem of the origin of species.8) During his time there, Wallace continued his self-education in science and began to publish a series of scientific papers. As part of his research, he also collected large numbers of insects, birds and mammals. In 1852, Wallace was returning home when disaster struck. The sailing vessel on which he was travelling caught fire and sank in the Atlantic Ocean. Wallace and the crew were rescued and returned safely to England.

Undaunted, Wallace prepared for another collecting expedition, this time to the Malay Archipelago; what is now Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia and East Timor. With the help of government money for his ticket, Wallace arrived in the bustling entrepôt of Singapore on 18 April 1854.

Over the next eight years Wallace made dozens of expeditions. His voyage correspondence was recently published, which together with his illuminating book The Malay Archipelago (1869), paints a rich picture of the peoples and nature of the 1850s and 1860s.9 Ultimately Wallace’s collection totalled 125,660 specimens of insects, birds, shells and mammals. In inflated versions of the story, Wallace painstakingly collected all of these specimens himself. But recent historical research has revealed that Wallace employed more than 30 fulltime assistants to aid him in his task, one of whom, Charles Allen and his own assistants, collected about 40,000 specimens.10 Altogether, Wallace’s assistants, particularly a Malay lad named Ali from Sarawak, probably collected more than half of the total number.

Wallace's faithful Malay assistant Ali.

Wallace's faithful Malay assistant Ali.

In 1855, while staying in Sarawak, Wallace wrote his first theoretical paper on species: “On the law which has regulated the introduction of new species.” In heroic accounts of Wallace, the paper is represented as if it was the first to have outlined the modern theory of evolution minus only the “mechanism” of natural selection.

In fact, the paper’s original sources and meanings were quite different, and far more modest. The paper did not even mention that species change. It argued that when new species were created during earth’s history, they always appeared in the same place as a similar species. Wallace was only testing the waters, not yet ready to come out of the closet publicly as an advocate of unorthodox views like evolution.

Nevertheless, it is absolutely clear that Wallace privately believed that species evolve. He was not searching for a solution to a problem or mystery. He most certainly was not searching for a “mechanism.” This is a modern idea. Wallace was interested in the topic of the gradual change of species over time. He was convinced it was a purely natural, and not a supernatural process, and he planned to write a book on the subject when he returned home.

In 1856, Wallace began to realise that in the west of the Malay Archipelago the species of animals were more Asian in type, while towards the east, the animal species were more Australian. Wallace would eventually divide the archipelago into two biological regions and the line between them, roughly between Bali and Lombok, was named after him – The Wallace line.

Adaptation

In 1858, Wallace was living on the tiny volcanic island of Ternate, one of the fabled Spice Islands of Indonesia, just west of New Guinea. He had come to procure the rare and beautiful Birds of Paradise that live only in and around New Guinea. It was on Ternate that Wallace conceived an explanation as to how species come to be adapted to their environments.11 This was a radical departure from his previous thinking. He had never looked for an explanation for adaptation before. Indeed he thought that traditional ideas of species adaptation smacked of shallow and old-fashioned thinking. So what made him change his mind?

The Red Bird of Paradise of New Guinea. This was what Wallace went to search for in 1858 in Ternate, Indonesia.

The Red Bird of Paradise of New Guinea. This was what Wallace went to search for in 1858 in Ternate, Indonesia.

The heroic story of Wallace is based on his recollection of what happened many years later, and after he had read Darwin’s Origin of Species. This is extremely problematic for two reasons. Firstly, retrospective accounts are not the same as contemporary evidence. Indeed, because historians have found recollections to be so inaccurate and untrustworthy, they are worth very little for understanding what a scientist was really doing many years before. Secondly, Wallace’s recollections are tainted by the fact that he had read Darwin and eventually his Life and Letters (1887). Therefore, Wallace’s stories as an old man are not independent attestations.

In 1858, Wallace elaborated his new ideas in his so-called Ternate essay: “On the tendency of varieties to depart indefinitely from the original type.” For many years Wallace’s essay was described as espousing exactly the same theory as Darvin’s. But the more historians have analysed it, the more clearly it has been revealed to be quite a different theory, but with some basic parallels to Darwin’s. Wallace certainly did originate a version of natural selection independently of Darwin.

What happened next has been surrounded by confusion and conspiracy theories for decades. Wallace did not send his essay to a journal. Instead he sent it to Darwin with the request that, if Darwin thought it suitable, it be forwarded to the great geologist Sir Charles Lyell. Here, the conspiracy theories mount thick and fast. Firstly, it was long claimed that Darwin lied about when he received Wallace’s letter. This has now been fully refuted.12 Secondly, it has been claimed that Darwin might have borrowed from Wallace’s essay. There is no evidence for these claims at all.

The remaining conspiracy theories are equally the sort of stories that could only have been told by recent writers quite unfamiliar with Victorian science and society: It is claimed that it was improper to publish Wallace’s paper without his explicit permission (false); that his paper ought to have been, according to the rules of the day, published on its own or at least ahead of anything by Darwin (false). And so forth.

It would have been perfectly acceptable and normal to send Wallace’s essay for publication. But Darwin must have felt awkward about being involved in the matter and asked his colleagues to decide what to do. In the end Lyell and the botanist Joseph Hooker had some unpublished writings by both Darwin and Wallace read together at a meeting of the Linnean Society of London in July 1858. Thus Darwin and Wallace shared the priority equally of first publicising the new idea. It was the first announcement of the modern theory of evolution by natural selection. Retrospectively it was a great event. But short papers do not a revolution make.

The following year, Darwin published a condensed version of his 20 years of work. This was On the Origin of Species. It was this book with its masses of new facts and converging forms of evidence which, within 15 years or so, convinced the international scientific community that evolution is a fact. It was the impact of this revolutionary book that shot Darwin to such unrivalled fame and reputation. Wallace became one of Darwin’s most ardent friends and supporters. And he always insisted that the theory was mostly Darwin’s work.

On his return to Britain in 1862, Wallace was no longer an obscure collector. He had become a well-known player in the scientific community. His reputation was forever linked with Darwin because of his own independent discovery. This no doubt helped the acceptance of Darwin’s book. Wallace was a great naturalist and a pioneer of the study of the biodiversity of Southeast Asia. He continues to inspire biologists and conservationists to this day. But he was not a dupe or a victim. Only proper historical method allows us to uncover the truth about the past and dispel the darkness of conspiracy theories or plain wishful thinking.

Dispelling the Darkness uncovers the true story of Darwin and Wallace and the theory of evolution. Published by World Scientific Publishing Co., 2013.

Dispelling the Darkness uncovers the true story of Darwin and Wallace and the theory of evolution. Published by World Scientific Publishing Co., 2013.

Dr John van Wyhe is a historian of science at the National University of Singapore who specialises in Darwin and Wallace. For several years a Bye-Fellow of Christ's College, Cambridge, he is also the Director of Darwin Online and Wallace Online and the author of 10 books and numerous articles on the history of science.

REFERENCES

van Wyhe, J. (2013). Dispelling the darkness: Voyage in the Malay Archipelago and the discovery of evolution by Wallace and Darwin. Singapore; New Jersey: World Scientific. (Call no.: R 576.82092 VAN)

van Wyhe, J. (2014). Charles Darwin in cambridge: The most joyful years. Singapore; New Jersey: World Scientific. (Call no.: R 576.82092 VAN)

NOTES

-

See van Wyhe, J. (2013). Dispelling the darkness: Voyage in the Malay Archipelago and the discovery of evolution by Wallace and Darwin. Singapore; New Jersey: World Scientific. (Call no.: R 576.82092 VAN) ↩

-

See van Wyhe, J. (2014). Charles Darwin in cambridge: The most joyful years. Singapore; New Jersey: World Scientific. (Call no.: R 576.82092 VAN) ↩

-

Barlow, N. (Ed.). (1958). The autobiography of Charles Darwin 1809–1882. With the original omissions restored. London: Collins. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Barlow, 1958. ↩

-

Barlow, 1958. ↩

-

Barlow, 1958. ↩

-

For many years it was said that Darwin was not really the naturalist, but more of a social companion to the ship’s captain. This has recently been refuted, see van Whye, J. (2013, September). “My appointment received the sanction of the Admiralty”: Why Charles Darwin really was the naturalist on HMS Beagle. Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences, 44 (3), 316–326. Retrieved from DOI.Org website. ↩

-

See van Whye, J. (2014, Winter). A delicate adjustment: Wallace and Bates on the Amazon and “the problem of the origin of species”. Journal of the History of Biology, 47 (4). 627–659. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

van Whye, J., & Rookmaaker, L.K. (Eds.). (2013). Alfred Russel Wallace: Letters from the Malay Archipelago. Oxford: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSEA 508.092 WAL); van Wyhe, J. (Ed.). (2015). The annotated Malay Archipelago by Alfred Russel Wallace. Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.8 ANN) ↩

-

See Rookmaaker, K., & van Wyhe, J. (2012, December). In Wallace’s shadow: The forgotten assistant of Alfred Russel Wallace, Charles Allen. Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 85 (2), 17–54. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

For many years it was believed that Wallace was actually on the nearby island of Gilolo, but that mistake has now been laid to rest. See van Wyhe, 2013, pp. 202–204. ↩

-

See van Wyhe, 2013, pp. 225–226, 358 note 692; van Wyhe, J., & Rookmaaker, K. (2012, January). A new theory to explain the receipt of Wallace’s Ternate Essay by Darwin in 1858. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 105 (1), 249–252. Retrieved from DOI.Org website. ↩