The Secret Maps of Singapore

Hidden temples and food haunts are just some of the things found in two psychedelic maps published in the 1980s. Bonny Tan explores the origins of these one-of-a-kind maps.

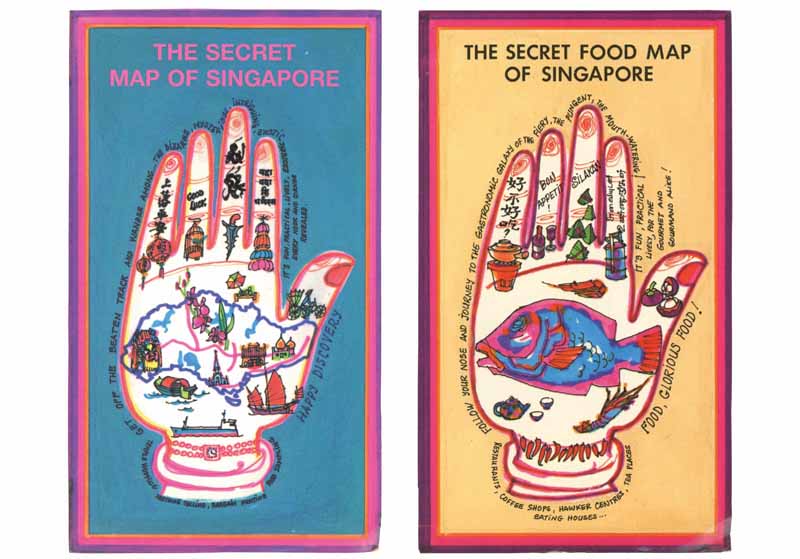

The Secret Map of Singapore (left) and The Secret Food Map of Singapore (right) were released in 1986 and 1987 respectively. The Secret Map of Singapore. All rights reserved. Mowe, Ropion, Hunt, 2014. The Secret Food Map of Singapore. All rights reserved, Ropion, Hunt, 2014. .

The Secret Map of Singapore (left) and The Secret Food Map of Singapore (right) were released in 1986 and 1987 respectively. The Secret Map of Singapore. All rights reserved. Mowe, Ropion, Hunt, 2014. The Secret Food Map of Singapore. All rights reserved, Ropion, Hunt, 2014. .

The Secret Map of Singapore (1986) and its companion, The Secret Food Map of Singapore (1987), were created by three women whose sense of adventure led them to explore unusual corners of the island. The vividly coloured hand-drawn maps highlight little-known and often forgotten facets of Singapore’s culture and flavours – long before it became fashionable for Singaporeans to reconnect with their own heritage. Unlike the staid text-based food guides produced in the 1980s,1 these map-centric guides provide visual impressions of places by locating them in the physical landscape, in the process giving context and lending immediacy to the everyday activities of the average Singaporean.

Colourful Cartographers

Three firm friends – Rosalind Mowe, Anne Ropion and Elyane Hunt – all saw Singapore with unconventional eyes as they had grown up and lived overseas and were widely travelled. Multilingual and of mixed ancestry, the women met while doing business at Tanglin Shopping Centre: French nationals Anne and Elyane operated Gompa, a shop selling Asian and Middle Eastern antiques,2 while Rosalind, the only Singaporean in the trio, had an outlet selling Thai silk.

The women’s interest in the unusual and offbeat in Singapore and their love for food were just some of the things that drew them together.3 But they were no passive observers in a rapidly developing island-city. Their passion for their adopted home and their zeal to show tourists and locals the hidden yet fascinating sights of an unchanged, older Singapore drove them to create these unusual maps.4

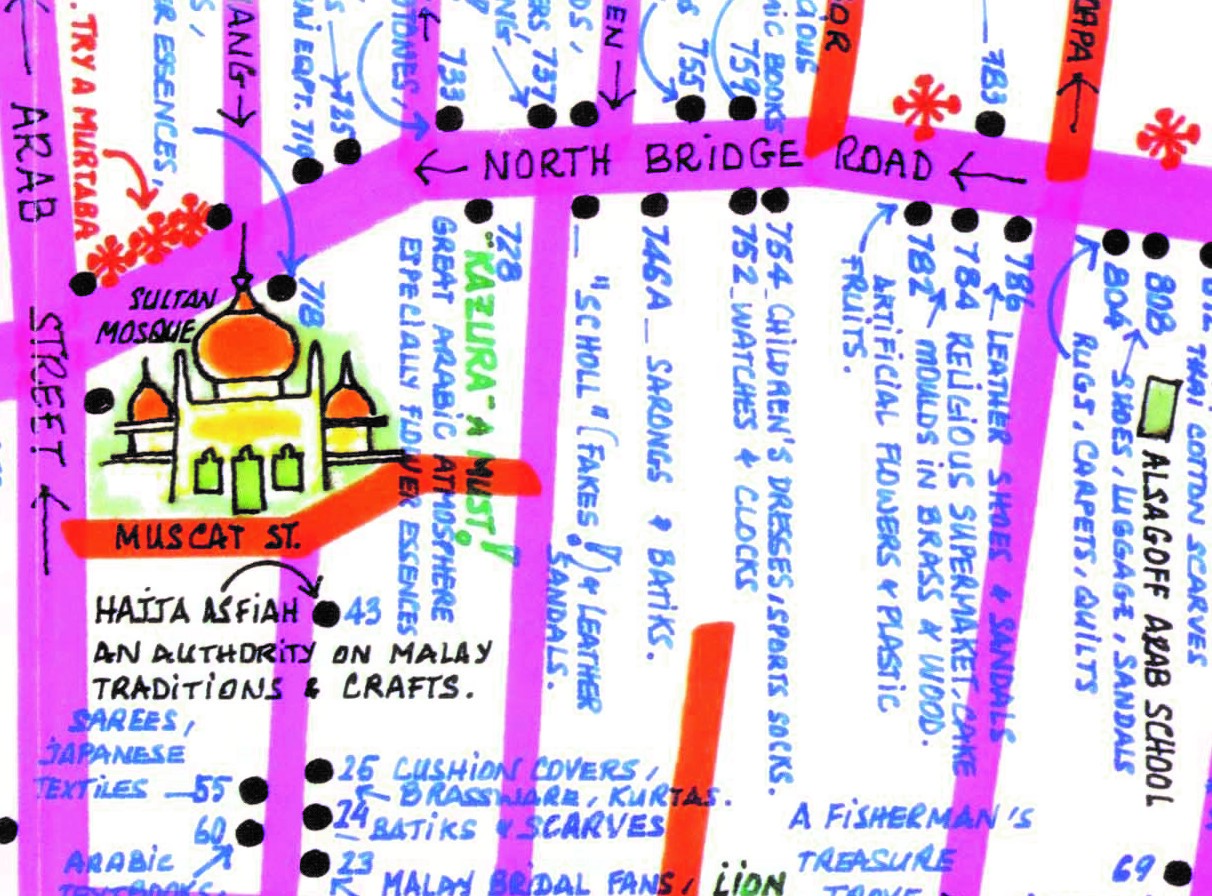

Elyane took the lead in developing the maps, deciding on the entries and the focus. Besides being conversant in French, Italian and German, Elyane is also fluent in Arabic and was thus able to provide insights to places in Singapore such as Kampong Glam, where the Arabic culture is most vibrant. Her fascination with Peranakan (Straits Chinese) architecture found the group exploring the ornamentation and finer details of traditional houses in neighbourhoods such as Joo Chiat and Geylang.5

Rosalind, on the other hand, is of mixed Chinese and Indian heritage. She picked up Cantonese growing up in Hong Kong but is also conversant in Malay. With these linguistic gifts, Rosalind helped the others navigate the local foodways and byways.6 Having been a teacher at St Theresa’s Convent, teaching maths, literature and English,7 Rosalind was likely to have injected an educational touch into the maps.

Their spouses were also drawn into the process, playing important parts in designing and marketing these maps. Anne Ropion’s husband, Michel, an engineer by training but an artist at heart, systematically drew the maps by hand. At a time when computers had not yet entered the lexicon of map design, this must have been a slow and painstaking process.

But it is not so much the hand-drawn finesse of the map that catches the eye. It is the colours. Bold and bright and bordering on the gaudy, Michel Ropion’s use of colours, they say, is a result of his upbringing in Cambodia.8 Then working as the Southeast Asia Representative of Bouygues,9 he fed his inherent love and talent for the arts by taking time to learn brush strokes, proportion and layout from a Chinese painter in Singapore.10

Eurasian Patrick Mowe, Rosalind’s husband, was at the tail end of his career, heading the MPH group of companies in Singapore and Malaysia, when the maps were published.11 Even so, it is likely that his influence in publishing and distribution helped in promoting the maps to foreign newspapers such as The New York Times, which carried brief articles on these maps in 1987 and 1988.

Mapping Out Secret Places

The first map, The Secret Map of Singapore, released around July 1986, took seven months of research, involving full days of exploration. Michel, working from early evenings and late into the night took another four months to draw and colour the map. The work required frequent on-site verification, resulting in a detailed map that traced unusual sights and untrodden areas, provided educational but sharp insights and often dispensed useful and sometimes hilarious advice.

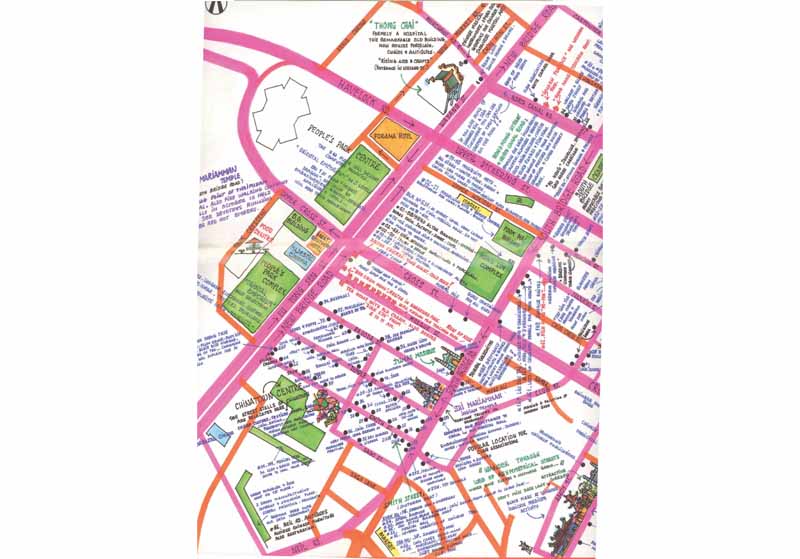

The main map is an outline of Singapore that has 93 locations highlighted, from tourist spots to interesting temples and eateries. The map unfolds into nine subsections: Chinatown, Orchard Road, Serangoon Road, Little India, Arab Street. Geylang, Geylang Serai – which includes the Joo Chiat and Katong areas – Holland Village and Toa payoh.

The bright colours on the map are not merely an element of graphic design. In effect, the colours function as codes for the different interests that a traveller may have – “black for antiques, curios and handicrafts; red for restaurants and coffee shops; green for recommended sightseeing; blue for interesting shops; and purple for the spiritual and the esoteric”.12 A bright pink highlights a route that is highly recommended. In the subsections, exact locations are indicated by the unit numbers of each outlet so that the map-reader is certain of the exact location. The Secret Map of Singapore retailed at S$4.90 at the time, a bargain considering how much work went into it.

Food outlets and good eats were already highlighted in The Secret Map of Singapore and thus the companion map, The Secret Food Map of Singapore naturally expanded on the research done previously. The second map was published around May 1987 and reportedly took 14 months to research and produce. The creators claimed to have visited as many as 10,000 outlets and eaten more than 1,000 meals in the course of researching The Secret Food Map of Singapore, from exotic Vietnamese and Thai eateries (well, exotic for the time) to humble hawker stalls selling comfort food such as goreng pisang (deep fried bananas).13 A similar colour coding system was adopted in this map with “red for Chinese food, green for Malay or Nonya food, black for other Asian food and blue for Western food”.14

Details of South Bridge Road in Chinatown as seen in The Secret Map of Singapore. The Secret Map of Singapore. All right reserved. Mowe, Ropion, Hunt, 2014.

Details of South Bridge Road in Chinatown as seen in The Secret Map of Singapore. The Secret Map of Singapore. All right reserved. Mowe, Ropion, Hunt, 2014.

A 1983 photograph of Smith Street, which is part of the Chinatown Conservation Area. From the Lee Kip Lin Collection. All rights reserved. Lee Kip Lin and National Library Board, Singapore 2009.

A 1983 photograph of Smith Street, which is part of the Chinatown Conservation Area. From the Lee Kip Lin Collection. All rights reserved. Lee Kip Lin and National Library Board, Singapore 2009.

A 1983 photograph of South Bridge Road, between Mosque and Pagoda streets, with Sri Mariamman Temple and Jamae Mosque on the right. From the Lee Kip Lin Collection. All right reserved. Lee Kip Lin and National Library Board, Singapore 2009.

A 1983 photograph of South Bridge Road, between Mosque and Pagoda streets, with Sri Mariamman Temple and Jamae Mosque on the right. From the Lee Kip Lin Collection. All right reserved. Lee Kip Lin and National Library Board, Singapore 2009.

A First in Mapping

Prior to this, articles about food and places of interest in the newspapers may have had accompanying maps15 that oftentime seemed like an afterthought, but there was nothing that showcased local cuisine and traditional crafts in the cartographic manner that these map-guides achieved. Tourist maps of the time usually featured the usual sights and icons, whereas these maps revealed hidden places, including tips on where to sit on benches and “study exceptional style old houses” (answer: “at [the] corner of Lorong 19 and Lorong Bachok” in Geylang) or oddities like where to purchase “ Chinese musical instruments, opera costumes and weapons, and Japanese martial art” (answer: on Merchant Road). Even details such as the telephone number of a master gasing (spinning top) maker or where to buy mosquito nets were studiously included in the map.

An elderly lady dictating her letter to a professional letter writer in Kreta Ayer, who set up his makeshift stall along a five-foot way, circa late 1970s. From the Kouo Shang-Wei Collection 郭尚慰收集. All rights reserved, Family of Kouo Shang-Wei and National Library Board Singapore 2007.

An elderly lady dictating her letter to a professional letter writer in Kreta Ayer, who set up his makeshift stall along a five-foot way, circa late 1970s. From the Kouo Shang-Wei Collection 郭尚慰收集. All rights reserved, Family of Kouo Shang-Wei and National Library Board Singapore 2007.

Interior of a pre-war coffee shop located on New Bridge Road, taken in 1992. From the Lee Kip Lin Collection. All rights reserved. Lee Kip Lin and National Library Board, Singapore 2009.

Interior of a pre-war coffee shop located on New Bridge Road, taken in 1992. From the Lee Kip Lin Collection. All rights reserved. Lee Kip Lin and National Library Board, Singapore 2009.

The interior of a traditional Chinese medicine shop located on New Bridge Road, taken in 1983. From the Lee Kip Lin Collection. All rights reserved. Lee Kip Lin and National Library Board, Singapore 2009.

The interior of a traditional Chinese medicine shop located on New Bridge Road, taken in 1983. From the Lee Kip Lin Collection. All rights reserved. Lee Kip Lin and National Library Board, Singapore 2009.

A certain joie de vivre comes across in the descriptions of the sights and senses encountered in Singapore. For example The Secret Food Map notes that “The last reported tiger was killed in Singapore in 1930. But even if the tiger’s days are over, you can still eat snakes, bear’s paws, turtles, iguanas, crocodiles, ox testicles, frogs, chicken feet, sea slugs and fish maw” in this city. The maps almost transports one vicariously to places where few tourists venture. Chinatown is described as “still reeking with atmosphere of early immigrants” and Geylang Serai is “reputed to be the refuge of the ‘Chinese Mafia’”. With tongue-in-cheek humour, the map tries to educate the first-time traveller on the various ways of eating in Singapore: the Chinese, for example, “eat and run!”: when partaking of Malay cuisine, “don’t ask for a knife. Fork and spoon will separate meat from bone!”; at Indian “eating places don’t expect a plate! The banana leaf is not a place mat”; and “when eating sushi [at Japanese places], acrobatic skills [are] required.’

The map creators were especially adept at pointing out spirit houses, temples and traditional places of worship – whether Buddhist, Taoist, Hindu or Islamic. Besides including well-known houses of prayer, The Secret Map of Singapore also highlights private homes with interesting altars such as those on Joo Chiat Road or more morbidly, the location of a Chinese undertaker on Jalan Pinang in the Kampong Glam neighbourhood. Simple down-to-earth places such as an Indian laundry shop and a children’s bicycle shop did not go unnoticed. High-end eateries such as Shima, a distinguished Japanese restaurant, are highlighted as well as Hainanese-style pseudo-Western restaurants such as Jack’s Place. Making no distinction between religion, class or culture, the maps bring together all that make Singapore unique. 1

For the historian, the maps pinpoint the locations of traditional but now barely existing activities and outlets in various neighbourhoods. For example “counters for remittance to China in (an) old medical hall” is located at 211 South Bridge Road in the heart of Chinatown, while ready-made popiah (spring roll) skins and pie tee (crispy dough cups) are prepared at Kway Guan Huat in the Peranakan enclave at 95 Joo Chiat Road. Incredibly, Kway Guan Huat still stands at its original site today, albeit in a more gentrified neighbourhood, and Shima restaurant re-opened in June 2014 at the Goodwood Park Hotel – where it used to be way back in the 1980s.

The Secret Food Map was soon followed by The Secret Map of Sydney, which was released in October 1987.16 The Secret Map of Singapore was reprinted in 1990, with research updates by Andrew Blaisdell and Adeline Ropion.17 Even so, changes to Singapore’s landscape were so swift that although only three years had lapsed, the reprinted map was revised with 88 highlights instead of the 93 shown in the original.18

1980s photograph of the Sultan Mosque located at 3 Muscat Street. GP Reichelt Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

1980s photograph of the Sultan Mosque located at 3 Muscat Street. GP Reichelt Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Details of Kampong Glam as seen in The Secret Map of Singapore. The Secret Map of Singapore, 1986. All rights reserved, Mowe, Ropion, Hunt, 2014.

Details of Kampong Glam as seen in The Secret Map of Singapore. The Secret Map of Singapore, 1986. All rights reserved, Mowe, Ropion, Hunt, 2014.

Shop selling rattan-weaved goods at Arab Street in the 1980s. GP Reichelt Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Shop selling rattan-weaved goods at Arab Street in the 1980s. GP Reichelt Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A man making murtatuk in the Kampong Glam area in 1991. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A man making murtatuk in the Kampong Glam area in 1991. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Bonny Tan is a Senior Reference Librarian at the National Library of Singapore. Her interest in the obscure things about Singapore led her to re-examine two little known maps and found herself surprised by their contents.

REFERENCES

Blaisdell, A. (1990). The secret map of Singapore. Retrieved from Google site.

Chua, R. (1986, August 23). Surprising Singapore. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Chuang, P.M. (1987, December 28). MPH chief to start new chapter in his life. The Business Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Crossette, B. (1987, January 11). Travel advisory: Find the unusual in Singapore. The New York Times. Retrieved from The New York Times website.

De, S.J. (1981, June 12). Browsers’ des’ delight. The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Dining map of Singapore. (1988, March 13). The New York Times. Retrieved from The New York Times website.

Ong, S.C. (1987, May 28). Care for spicy snails and midnight murtabak? The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Oon, V. (1980, April 6). Bon appetit! The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Linkedln. (2014). Michel Ropion. Retrieved from Linkedln website.

Ropion, M., Hunt, E., & Mowe, R. (1986). The secret map of Singapore [cartographic material]. Singapore: s.n. (Call no.: RSING 912.5957 SEC)

Ropion, M. (1987). The secret food map of Singapore. Singapore: Ropion Hunt Mowe. Retrieved from PublicationSG.

Tee, H.C. (1999, May 7). Cookbook author can’t cook at first. The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Teo, T.W. (1978, June 27). Asia-Pacific lays out a special $20m winner. The Business Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Wong, S-F. (1988, July 24). Guides to better eating. The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG

NOTES

-

Robinson, M., Muehrcke, K., & Guptil, S.C. (Eds.). (1995). Elements of cartography (p. 12). New York: John Wiley & Sons. (Call no.: R 526 ELE) ↩ ↩2

-

De, S.J. (1981, June 12). Browsers’ des’ delight. The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Chua, R. (1986, August 23).Surprising Singapore. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Crossette, B. (1987, January 11). Travel advisory: Find the unusual in Singapore. The New York Times. Retrieved from The New York Times website. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 23 Aug 1986, p. 1. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 23 Aug 1986, p. 1. ↩

-

Tee, H.C. (1999, May 7). Cookbook author can’t cook at first. The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 23 Aug 1986, p. 1. ↩

-

The Bouygues Offshore Company based in Paris specialised in the construction of marine structures. Teo, T.W. (1978, June 27). Asia-Pacific lays out a special $20m winner. The Business Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Linkedln. (2014). Michel Ropion. Retrieved from Linkedln website. ↩

-

Chuang, P.M. (1987, December 28). MPH chief to start new chapter in his life. The Business Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ropion, M., Hunt, E., & Mowe, R. (1986). The secret map of Singapore [cartographic material]. Singapore: s.n. (Call no.: RSING 912.5957 SEC) ↩

-

Ong, S.C. (1987, May 28). Care for spicy snails and midnight murtabak? The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ropion, Hunt, & Mowe, 1986. ↩

-

Oon, V. (1980, April 6). Bon appetit! The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 28 May 1987, p. 2. ↩

-

Blaisdell, A. (1990). The secret map of Singapore. Retrieved from Google site. ↩

-

Blaisdell, 1990. ↩