Searching for Singapore in Old Maps and Sea Charts

Kwa Chong Guan dissects the history of maps and tells us how Singapore was perceived and located in early modern European maps of the region.

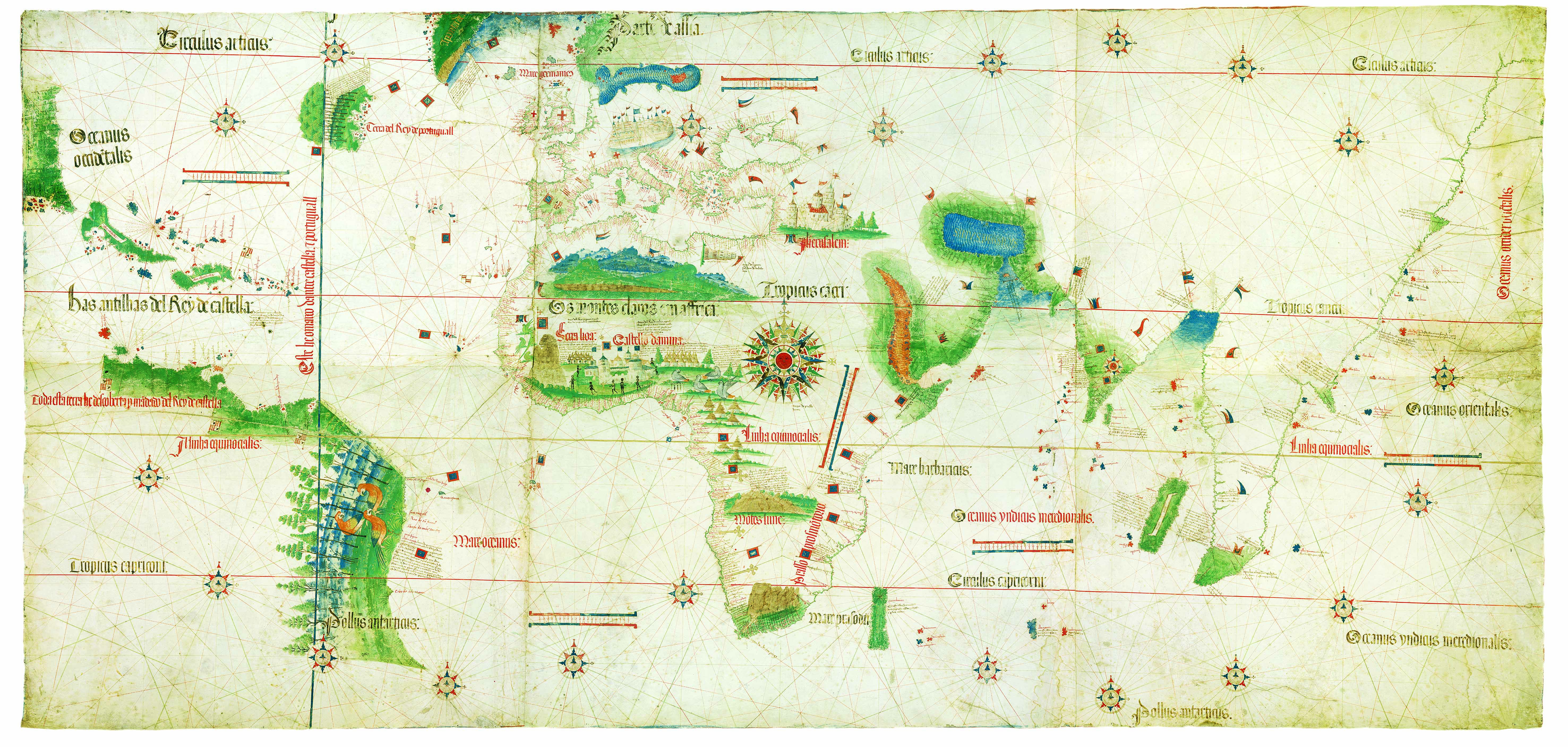

Cantino Chart, Anonymous 1502. Based on the latest information from Portuguese explorations, secretly obtained by Albert Cantino, the map depicts the Malay Peninsula as an elongated promontory that reaches the south of the equator. Biblioteca Estense Universitaria, Modena, C.G.A. Permission from the Ministry of Arts, Culture and Tourism, Italy.

Cantino Chart, Anonymous 1502. Based on the latest information from Portuguese explorations, secretly obtained by Albert Cantino, the map depicts the Malay Peninsula as an elongated promontory that reaches the south of the equator. Biblioteca Estense Universitaria, Modena, C.G.A. Permission from the Ministry of Arts, Culture and Tourism, Italy.

The study of maps has traditionally been the purview of geographers. Maps are a documentation of the landscapes that geographers study, and as such, have not attracted the attention of historians whose primary concern is the study of events. But maps document the spatial context within which the events that historians study occur. This essay examines how early modern European maps and sea charts of Asia are significant for what they show of Singapore’s historical significance and strategic location two centuries before Stamford Raffles claimed it.

The National Library’s acquisition in 2012 of Dr David E. Parry’s collection of early modern maps of Insulae Indiae Orientalis (or, the East Indian Islands) is a major step forward in the search for Singapore’s historical roots in old maps and sea charts. Parry is a soil scientist and remote sensing expert who used a variety of modern and not-so-modern topographic and thematic maps of the region in the course of his work. Over the course of 25 years while working in Indonesia, he amassed an outstanding collection of historic maps of island Southeast Asia1 that contains much information on issues of Singapore’s historical significance and its strategic location.

More than a Reflection of Landscapes

We accept that the maps in Parry’s collection are an accurate reflection of Southeast Asia’s landscape in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, just as we accept that the maps we download from Google today are accurate and reliable reflections of what we see around us, helping us to get from point A to point B in the quickest possible time. If we do not reach our destination by following the signs and symbols we read on the map, we assume we missed a landmark – a road junction we should have turned at, but did not; or a temple we saw, but could not find on the map – and we backtrack to look again around us for the signs and symbols marked on the map to get to our destination. In this sense, the map is not a reflection of the reality we see around us, but the reality into which we fit what we see around us.

Topographic maps, or street directories, as the historian of cartography J.B. Harley2 argues, “persuades” us to encounter what we should be seeing and searching for in the landscape around us. Maps, Harley says, are “inherently rhetorical images.” They persuade us to see our landscape in a particular context and perspective. Harley also argues that maps, “are never neutral or value-free or even completely scientific… They are part of a persuasive discourse, and they intend to convince.”

We believe in maps because they help us to locate ourselves in unfamiliar places, and because we think what maps tell us is both convincing and useful. But will there come a time when we question the accuracy and the adequacy of the map? Do we deem the map unreliable when we cannot match the hills we see in front of us on a trek with what is marked on the map? Or, when the map has symbols and signs of too many landmarks and features that confuse us, and we cannot match what we see around us with what is marked on the map? Do we reject those maps and look for another map that projects an image we find more convincing about the landscape around us?

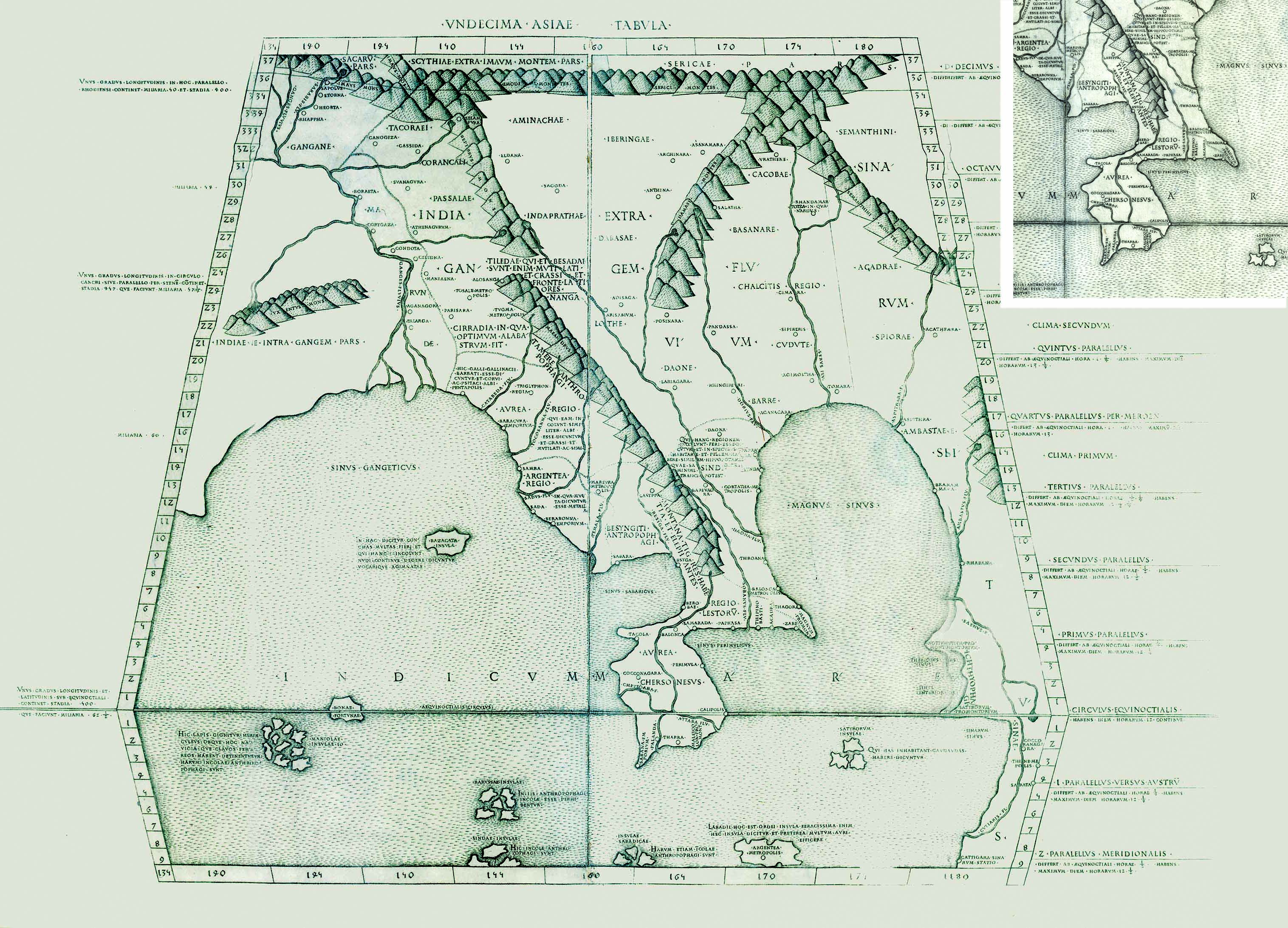

What do we make of a 16th-century Portuguese sea chart of the Straits of Melaka and Singapore that does not mark a Cingaporla, Cingatola or Cinghapola, (the old Portuguese transcriptions for Singapura) where we expect to see it? Is the chart therefore inaccurate and to be disregarded? Or, should we not ask why the Portuguese cartographer misrepresented the location of Cingaporla? Is Singapore the “Sabana Emporium” located on the southern edge of the Golden Khersonese or Golden Peninsula in the 16th-century rendition of a world map based on the work of the 2nd-century Greek astronomer Claudius Ptolemy? If so, then we should intensively study Ptolemy’s map for what else it can tell us about this earliest possible mention of a settlement on this island.

In reality, the early Portuguese, and all other European cartographers, were in a sense filling in the blank spaces of their maps with toponyms, geographical details and historical data of the lands they were exploring. In choosing what to mark on the maps, they were in fact documenting a vision of the East as lands of great wealth, the locus of King Soloman’s Ophir with its abundance of gold, silver and other gems which Ptolemy’s poetic reference to the Golden Khersonese confirmed. Asianus in Latin (or Asianos in Greek) was believed to be the source of things exotic: silks and spices, aromatic herbs, intoxicating drugs, places of golden opportunities. Was this continent of Asianus really located at the furthest edge of a flat world as depicted in medieval maps of the Christian world, or was the world a sphere as Ptolemy had calculated?

This essay argues that these early modern Portuguese, Dutch and English maps and charts of the landscape around our island are critical evidence of Singapore’s historical roots not because they are an accurate (or inaccurate) reflection of the landforms these Portuguese sailors encountered as they sailed through the Straits of Melaka and Singapore, but more importantly, because they were statements about Singapore’s location in a world of rich and exotic things these sailors believed they were sailing around.

These maps were rhetorical devices the Portuguese sailors must have found reassuring as they sailed into the hitherto uncharted waters of the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea. The maps and charts were comforting because they assured the Portuguese sailors that they would not sail off a flat world into nothingness, as they were taught in Christian theology. These early modern maps were not a representation of our 16th-17th century world, but a documentation of a Renaissance Europe constructing a new world of Asianus and itself. They depict a Europe coming to terms with itself as no longer the centre of the world, as depicted in their theological maps of the world, but having to rethink its place in relation to the new and vast continent of Asianus.3

The Legacy of Claudius Ptolemy

The view of the world as a sphere and not the flat disc of medieval European cartography is very much the legacy of Ptolemy, who developed in his work Geographike Huphegesis – or simply Geography as it is more commonly referred to – a grid system of describing and mapping the world that has become the basis of cartography today. Ptolemy borrowed from the work of earlier Greek geographers, namely Strabo, Eratosthenes, and Hipparchus of Nicaea. These early Greek geographers assumed that geography was more a science derived from philosophy and mathematics than a tradition passed on by sailors and navigators. These Greek philosophers were more interested in fundamental questions of the nature and shape of the earth – was it a flat disc or a sphere? – than documenting landforms of foreign lands as described by sailors and explorers.

As far as we know, it was Plato, in his work Phaedo, who argued that the earth must be spherical because the sphere is the most perfect mathematical form. Later Greek philosophers such as Aristotle refined the mathematics for a spherical earth. But it was Eratosthenes, perhaps the greatest of the ancient Greek geographers, who was the first to calculate the circumference of the earth based on the difference in the length of the shadows cast by the sun at noon in Alexandria and at Syene (modern Aswan). He also attempted to develop a grid for his maps which he based – in deference to the demands of sailors – on prominent landmarks such as Alexandria and the Pillars of Hercules. It was an irregular network of grids which his successor, the astronomer Hipparchus, radically improved upon.

Instead of pegging his grid to geographical and historical landmarks, Hipparchus worked out a grid pegged to the position of the stars. It was Hipparchus who divided the world into 360 latitudinal parts and 180 parallel longitudinal parts. Then came Ptolemy, whose skill and greatness lay in his ability to synthesise and improve upon the work of his predecessors.

Ptolemy may have been forgotten in medieval Europe, but not in the Islamic empires that emerged after the 7th century. A massive translation programme of much of the corpus of Greek philosophy and science was undertaken under the Abbasid caliphs al-Manșūr (reigned 754–78), Hārūn al-Rashīd (reigned 786–808) and al-Ma’mūn (reigned 813–33) which fundamentally shaped the nascent Islamic civilisation, and was the conduit through which Ptolemy and much of Greek philosophy and science was transmitted back to late medieval and Renaissance Europe.

Refugees fleeing the Turkish advance on Constantinople brought to Italy a number of Byzantine manuscripts, including Ptolemy’s Geography. The 1405 Latin translation of this seminal work caused a sensation. It inspired Iberian sailors and navigators to sail further afield in their search for alternative sea routes to Southeast Asia, the source of spices for which demand was growing exponentially in Europe. These explorers started revising and expanding the classical navigation guides, or periplus, to the coasts they were sailing along. From the 14th century onwards, Iberian and Italian navigators started producing a series of sea charts (or portolanos) to accompany the textual navigational guides they had been using previously.

The secret Portuguese world chart – a copy of which the Italian agent Alberto Cantino smuggled out of Lisbon in 1502 and now bears his name as the Cantino Chart – comprehensively summarises Portuguese knowledge of the seas at the beginning of the 16th century. On the Cantino Chart, the African coast is as we would recognise it today, with Portuguese flags planted at their respective landfalls. The Indian coast, which the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama reached in 1498, is also recognisable on this chart. But beyond the Indian Ocean is still a blank and the mapping of Insulae Indiae Orientalis reflects Ptolemy’s work as rewritten by 10th and 11th century Byzantine clerics who incorporated Byzantine and earlier Arabic data into the text and compiling maps they attributed to Ptolemy.

Ptolemy’s maps and system of anticipating what lay over the horizon of the ocean provided more assurance and inspiration than the flat world map as depicted in the flawed Topographia Christiana (Christian Topography) of the 6th century. More importantly, the Iberian navigators of the 15th century found Ptolemy’s maps and system of longitude and latitude coordinates, as copied and modified by various Byzantine clerics and earlier Arab geographers, a far more credible and reliable model of the world than the medieval world maps they had inherited. It enabled them to accurately map the locations of places they were sailing to as compared to the flat maps of the world they were familiar with. Ptolemy’s influence is clear among the leading European cartographers of the 16th century.

The Ptolemaic vision of Indiae Orientalis was not corrected until around 1513 with the publication of Livro de Francisco Rodrigues (The Book of Francisco Rodrigues) by the self-styled “Pilot-Major of the Armada that discovered Banda and the Moluccas”. This is one of the earliest navigational guides with 26 maps and charts on sailing from Europe to East Africa and onwards to Melaka and then the Moluccas (Maluku) and north China. Other rutters and charts provided new data to revise Ptolemy’s map.

The German cartographer Martin Wald seemüller (1470–1518) led the revision and updating of the Ptolemaic model to incorporate new information that 15th-century voyagers were bringing back. His 1507 Universalis Cosmographia map of the world has today attained World Heritage status as the first map to identify America as a separate land mass. In addition to the obligatory 27 Ptolemaic maps, Waldseemüller also published another 20 “modern maps” that were revised in various editions.

Another German cartographer, Sebastian Münster (1488–1552) produced a new edition of Ptolemy’s Geography in 1540 with 12 new maps and a major text, and published Cosmographia four years later. The work went through some 56 editions in six languages in the following century. Münster’s world map continued to follow Ptolemy’s principle, in which all the continents were linked up and enclosed the Indian Ocean, even as accumulating knowledge showed otherwise. It was only in the 17th century that this Ptolemaic image of Asia was finally abandoned.

Tabula Asiae XI, Arnold Buckinck, 1478. The earliest map in the National Library's rare maps collection is a 1478 Ptolemaic map. The “Aurea Chersonesus” (or Golden Chersonese) in the map refers to the Malay Peninsula. Collection of the National Library, Singapore.

Tabula Asiae XI, Arnold Buckinck, 1478. The earliest map in the National Library's rare maps collection is a 1478 Ptolemaic map. The “Aurea Chersonesus” (or Golden Chersonese) in the map refers to the Malay Peninsula. Collection of the National Library, Singapore.

Recovering Ptolemy’s Legacy in Southeast Asia

It was the Greco-Latin texts, in particular those by Ptolemy, that the pioneering generation of historians studied to make sense of the historical landscape of Southeast Asia they were reconstructing. George Coedès, who became the doyen of early Southeast Asian history, started his career by publishing an edition of the Greek and Latin texts on Southeast Asia in 1910. Louis Renou’s 1925 edition of Book VII of Ptolemy’s Geography is still today one of the better guides to a difficult text.4 The lawyer and barrister, Dato Sir Roland Braddell, pioneered the study of the Ptolemaic references to Malaya in the 1930s.5

A new era in the study of the historical geography of Malaya started with the establishment of a Department of Geography at the University of Malaya and the recruitment of Paul Wheatley in 1952. Wheatley focused on the historical geography of Malaya and studied classical Chinese to access the Chinese texts on early Southeast Asia. His 1958 University of London doctoral thesis The Golden Khersonese: Studies in the Historical Geography of the Malay Peninsula Before A.D. 1500, published in 1961, remains today a benchmark reference text. In successive chapters he collated and translated the classical Chinese, Greek, Latin, Indian and Arab textual references to the historical geography of Malaya.

Wheatley also reached out to Prof Hsu Yun-ts’iao, a driving force in the establishment of a tradition of Chinese scholarship on Singapore and the Nanyang at the old Nanyang University and the older South Seas Society. Hsu spent much of his academic career searching Chinese texts for references to early Singapore. Gerald R. Tibbetts, who was researching Arab trade in early Southeast Asia at the University of Khartoum, was asked to collate Arab material relating to the Malay Peninsula, a summary of which was published in the Malayan Journal of Tropical Geography. Tibbetts continued to collate the Arab texts containing material on Southeast Asia, part of which has been published.6

All these studies of Singapore’s early historical geography and that of the Malay Peninsula stopped with the arrival of the Portuguese at Melaka. The development of Portuguese and Dutch cartography of Southeast Asian waters within an evolving Ptolemaic model of the world has not attracted the attention it deserves. The exception is the translated edition by J.V.G Mills, a Puisne Judge of the Straits Settlement, of the Declaracam de Malaca e India Meridional com o Cathay by the Eurasian explorer and mathematician Manuel Godinho d’Erédia.7 Mills was also commissioned in 1934 “to make a collection of early maps and charts relating to the Malay Peninsula” and “spent many months during the summer of that year examining available material in the libraries of the British Museum, the Royal Geographical Society, the School of Oriental Studies and the Royal Asiatic Society.”8 This collection of 208 maps, which starts with copies of maps attributed to Ptolemy to the 1502 Cantino Chart and ends with 1879 maps of the peninsula, are now deposited in the Lee Kong Chian Library at the National Library, Singapore.

Distinguishing the Old Straits from the New Straits

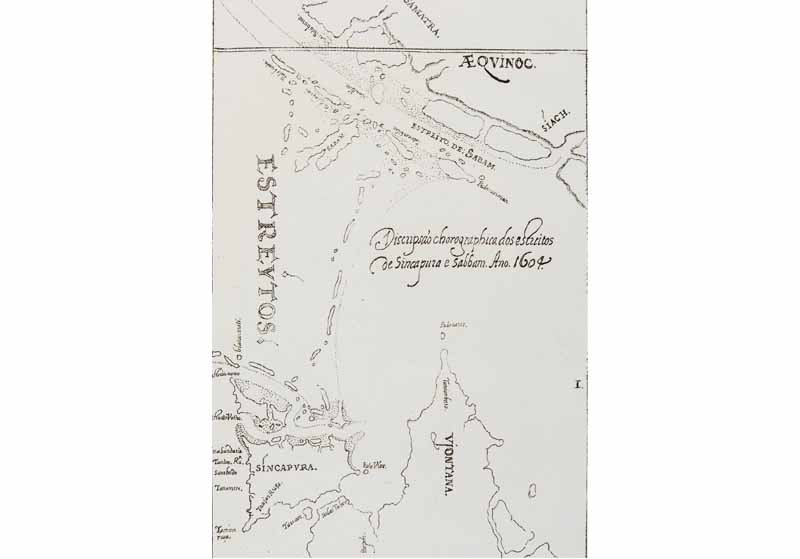

It fell to the polymath scholar of Malaysiana, Carl Alexander Gibson-Hill, to detect inconsistencies and discrepancies in d’Erédia’s demarcation of the four waterways for sailing past Singapore – the Johor Straits, the Keppel Harbour passage, the Sister’s Fairway (south of present-day Sentosa Island) and the Main Straits – and that of later sea charts. The 18th-century sea charts marked the waterway between Johor and Singapore as the “Old Straits,” but for the Portuguese mariners, the “Old Straits” was not the Johor Straits that they tried to avoid as the sultans of Johor controlled the estuary of the Johor River.

Through their Malay pilots, the Portuguese became aware of an alternative passage south of Singapore island, which d’Erédia marked as estreito velho or “old strait” in his maps. It fell to Gibson-Hill to sort out the confused nomenclature for the waterways in a much under-appreciated monograph published in 1956.9 Gibson-Hill’s interest in this problem of sailing past Singapore probably arose from his interest in sailing and boats. He was able to undertake this study of the evolving nomenclature for the four waterways for passage past Singapore because he had at his disposal, in the library of the old Raffles Museum, copies of 208 maps and charts relating to Singapore and Malay from the 16th to the 19th centuries that J.V.G Mills assembled in 1934.

Unfortunately, Gibson-Hill’s insights into what early European cartography can tell us about Singapore’s early modern history was ignored, if not dismissed, by the new generation of historians at the Department of History at the University of Malaya established in 1951 under Prof C. Northcote Parkinson. They took a very textual and archival documentary approach to Singapore history within its British colonial context. Parkinson’s successor as Raffles Professor, K.G. Tregonning, declared that “modern Singapore began in 1819. Nothing that occurred on the island prior to this has particular relevance to an understanding of the contemporary scene; it is of antiquarian interest only”. As a result, Gibson-Hill’s work was disregarded and the research undertaken by the History Department’s staff and students focused largely on the “modern” post-1819 history of Singapore.

It was not until 1999 when new interest in Gibson-Hill’s insights was revived in a Singapore History Museum publication entitled Early Singapore 1300–1819: Evidence in Maps, Text and Artefacts.10 The publication followed a 1999 exhibition of artefacts recovered from archaeological excavations on Fort Canning and its environs since 1984. The exhibition provocatively suggested that the archaeological evidence indicates a thriving settlement on Singapore since the beginning of the 14th century, which would then mark 1999 as the 700th anniversary of Singapore. However, the problem was linking the 14th-century port, which had been abandoned at the end of that century, to the East India Company outpost that Stamford Raffles established in 1819.

In his essay “Sailing Past Singapore”,11 Kwa Chong Guan argues that Gibson-Hill’s charting of the use and disuse of the various channels for sailing past Singapore in early modern times provides a link from the 14th-century emporium at the mouth of the Singapore River to the East India Company outpost established by Raffles. Based on the sea and the channels the mariners were using to navigate past Singapore and its 60-odd surrounding islands, there was much activity, as documented in the sea charts and maps. The Malays, Portuguese, Dutch and British were all manoeuvring and challenging each other for control of the waters around Singapore. Raffles’ establishment of an East India Company factory on Singapore was not so much about gaining territory but a continuation of this struggle for control over its waterways for British shipping in the region.

In another essay,12 Peter Borschberg draws attention to a little-known schematic map of a Dutch-Portuguese naval confrontation at the eastern entrance of the Tebrau Straits in October 1603, which the German publisher Theodore de Bry had included as an appendix in his multi-volume compilation of early 16th-century voyages and travels to the East and West Indies, Peregrinationum in Indiam Oriental et Indiam Occidentales. Borschberg traces the circumstances leading to this naval battle to the Sultan of Johor’s seizure, with Dutch aid, of a fully laden Portuguese carrack – the Santa Catarina – which was returning from Macao in February 1603. The Portuguese blockaded the Johor capital at Batu Sawa and captured and occupied the old capital at Johor Lama. It was during this Johor-Portuguese confrontation that the Dutch intervened in support of Johor and stepped up their attacks on Portuguese ships in the waters around Singapore. Johor-Dutch cooperation culminated in an alliance that provided the Dutch East India Company the rights and privileges to trade with Johor and an agreement to mount a joint attack on Portuguese-occupied Melaka.

This map shows the Old Strait (“estreito velho”) as a narrow channel running east-west of the southern coast of Singapore island. The New Strait (“estreito novo”) is found further south of the Old Strait. This detail is taken from a 19th-century facsimile of Manuel Godinho de Eredia’s 1604 map in Malaca, L’Inde Orientale et le Cathay. Collection of the National Library, Singapore.

This map shows the Old Strait (“estreito velho”) as a narrow channel running east-west of the southern coast of Singapore island. The New Strait (“estreito novo”) is found further south of the Old Strait. This detail is taken from a 19th-century facsimile of Manuel Godinho de Eredia’s 1604 map in Malaca, L’Inde Orientale et le Cathay. Collection of the National Library, Singapore.

A History Long Before 1819

From this perspective, these early modern sea charts are more than an encapsulation of European cartographic history of how Portuguese and Dutch mariners mapped landforms along the Straits of Melaka and Singapore in their search for the Golden Khersonese envisioned in the 2nd century by Ptolemy in faraway Alexandria. Instead, they point to a history that existed long before Singapore’s official founding in 1819. These early modern sea charts and maps of the Straits of Melaka and Singapore are windows into the complex maritime history of Singapore in the 300 years before Raffles stepped ashore on our island. More importantly, these visual documents point to the battle for the security and control of the Straits between the European merchant empires, and Singapore’s location in that struggle.

Several of the maps mentioned in this article are currently on display at the exhibition “Land of Gold and Spices: Early Maps of Southeast Asia” at level 11, National Library Building.

GEOlGRAPHIC: WHAT IS THE EXHIBITION ABOUT?

Curated by the National Library Board, “GeolGraphic: Celebrating Maps and their Stories” is a combination of exhibitions and programmes that explore maps and mapping in their historical and contemporary contexts. The maps – which date back to as early as the 15th century – are drawn from the collections of the National Library, Singapore, and the National Archives of Singapore and supplemented by rare maps specially flown in from Britain and the Netherlands. This is a unique opportunity to see printed and hand-drawn maps that are on public display for the first time in Singapore

GeolGraphic is currently taking place at the National Library Building until 19 July 2015. The exhibition takes place on different levels of the building.

L1 Singapore’s first topographical and City Map

L10 Land of Gold and Spices: Early Maps of Southeast Asia and Singapore

L11 Island of Stories: Singapore Maps SEA STATE 8 seabook l An Art Project by Charles Lim

MIND THE MAP: MAPPING THE OTHER

Presents the works of three Singapore-based contemporary artists who harness data collection and mapping strategies to investigate what lies beneath the surface of contemporary life.

L7 Bibliotopia l By Michael Lee

L8 Outliers l By Jeremy Sharma

L9 the seas will sing and the wind will carry us (Fables of Nusantara) l By Sherman Ong

Free guided tours of the exhibition are available every Sat and Sun until 19 July 2015. English tours run from 2 to 3pm and Mandarin tours from 2.30 to 3.30pm. Each tour is limited to 20 participants on a first-come-first-served basis. For inquiries, please email visitnls@nlb.gov.sg

A series of lectures on the theme of maps and mapping has been organised as part of GeoIGraphic as well as an interactive exhibition called MAPS!, now on at selected public libraries. For more information on all programmes, pick up a copy of GoLibrary or access it online at http://www.nlb.gov.sg/golibrary/

Kwa Chong Guan dissects the history of maps, and tells us how Singapore was perceived and located in early modern European maps of the region.

REFERENCES

Braddell, R.St.J. (1980). A study of ancient times in the Malay Peninsula and the Straits of Malacca and notes on ancient times in Malaya. Kuala Lumpur: Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. (Call no.: RDLKL 959.01 BRA)

Borschberg, P. (2010). The Singapore and Melaka Straits: Violence, security and diplomacy in the 17th century (pp. 60–112). Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 911.16472 BOR)

Gibson-Hill, C.A. (1956, December). Singapore: Old Strait and new harbour, 1300–1870. (Memoirs (Raffles Museum), No. 3). Singapore: Government Printers. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.51 BOG)

Godinho de Eredia, M. (1997). Eredia’s description of Malacca, Meridonial India and Cathay. Kuala Lumpur: Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. (Call no.: RSING 959.5118 GOD)

Mills, J.V. (1937, December). On a collection of Malayan maps in Raffles Library. Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 15 (3), 49–63. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Miskic, J.N., & Low, C-A, M.G. (Eds.). (2004). Early Singapore 1300s─1819: Evidence in maps, test and artefacts. Singapore: Singapore History Museum. (Call no.: RSING 959.5703 EAR)

Parry, D.E. (2005). The cartography of the East Indian islands: Insulae Indiae Orientalis. London: Countrywide editions. (Call no. RSING q912.59 PAR)

Tibbetts, G.R. (1979). Study of the Arabic texts containing materials on South-East Asia, oriental translation fundNew Series, Vol. 44). Leiden: E.J. Brill for the Royal Asiatic Society. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Wheatley, P. (1961). The Golden Khersonese: Studies in the historical geography of the Malay Peninsula before A.D. 1500. Kuala Lumpur: University of Malayan Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.5 WHE)

Wheatley, P. (1983). Nagara and commandery: Origins of the Southeast Asian urban traditions. Chicago: University of Chicago Dept. of Geography. (Call no.: RSEA 301.360959 WHE)

NOTES

-

See David E. Parry’s write up of his collection in his D.E.Parry, (2005). The cartography of the East Indian islands: Insulae Indiae Orientalis. London: Countrywide editions. (Call no. RSING q912.59 PAR) ↩

-

Harley, J.B. (2001). The new nature of maps: Essays in the history of cartography. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

See Jerry Brotton for a development of this argument in his Brotton, J. (1997). Trading territories: Mapping the early modern world. London: Reaktion Books. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Renou, L. (1925). La Géographie de Ptolémée. L’Inde. (vii, 1–4). Paris: Champion. (Call no.: RCLOS 911.54 PTO) ↩

-

Braddell, R.St.J. (1980). A study of ancient times in the Malay Peninsula and the Straits of Malacca and notes on ancient times in Malaya. Kuala Lumpur: Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. (Call no.: RDLKL 959.01 BRA) ↩

-

Tibbetts, G.R. (1979). Study of the Arabic texts containing materials on South-East Asia, oriental translation fund (New Series, Vol. 44). Leiden: E.J. Brill for the Royal Asiatic Society. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Godinho de Eredia, M. (1997). Eredia’s description of Malacca, Meridonial India and Cathay. Kuala Lumpur: Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. (Call no.: RSING 959.5118 GOD) ↩

-

Mills, J.V. (1937, December). On a collection of Malayan maps in Raffles Library. Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 15 (3), 49–63. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Gibson-Hill’s study was first published as Singapore: Notes on the history of the Old Strait, 1580–1850. (1954, May). Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 27 (1), (165), 163–214. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. It was expanded as Gibson-Hill, C.A. (1956, December). Singapore: Old Strait and new harbour, 1300–1870. (Memoirs (Raffles Museum), No. 3). Singapore: Government Printers. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.51 BOG) ↩

-

Miskic, J.N., & Low, C-A, M.G. (Eds.). (2004). Early Singapore 1300s─1819: Evidence in maps, test and artefacts. Singapore: Singapore History Museum. (Call no.: RSING 959.5703 EAR) ↩

-

See Sailing past Singapore. In Miskic & Low, 2004, pp. 95–105. ↩

-

A Portuguese-Dutch naval battle in Johor river estuary and the liberation on Johor Lama in 1603. In Miskic & Low, 2004, pp. 106–117 and Borschberg, P. (2010). The Singapore and Melaka Straits: Violence, security and diplomacy in the 17th century (pp. 60–112). Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 911.16472 BOR), which carries the narrative forward from the 1603 battle. ↩