The Music, Madness and Magic of Dick Lee

The “Mad Chinaman” was probably the first to push the boundaries of popular music in Singapore. Joy Loh profiles the enfant terrible of entertainment.

“What drove me to do what I did – it was to find myself and to make my statement as a Peranakan Chinese Singapore citizen of Asia and of the world”.

Writer, composer, singer, director, producer, clothing designer, talent agency owner and restaurateur. The multi-hyphenated Dick Lee has done it all, and there is precious little in the creative industry that he has not had a hand in. Lee bears the distinction of being one of the first entertainers to push the accepted boundaries of popular music and propel Singapore and Singapore music into the international arena. More importantly, he has helped nurture in Singaporeans a greater appreciation for locally produced music. Today, his significant body of work has become part of the cultural fabric of our history.

Dick Lee was born on 24 August 1956, the eldest of five children of Lee Kip Lee, a sixth-generation Peranakan (Straits Chinese) businessman and former president of the Peranakan Association, and his wife Elizabeth. He was named Lee Peng Boon Richard, but is known to most people as Dick Lee.

Music featured prominently in the younger Lee’s life. Growing up in a home where his father would play jazz and Indonesian keroncong1 and his mother’s favourite pop melodies on the record player, it was natural that music would come to inspire many of his creative pursuits. In his book Adventures of the Mad Chinaman, Lee recalls, “My earliest influence was the music of the 1960s… Dad loved big band, jazz, crooners, and keroncong, while my mother, in her 20s at that time, loved contemporary Western and Chinese pop music.”

Since an early age, Lee had shown a natural talent for creating music. By the time he was 11, Lee had “produced” his first musical starring his siblings and cousins. Among his early creations was an adaptation of the classic Chinese play Lady Precious Stream, which tells the story of a feisty daughter who defies her parents’ wishes that she enter into an arranged marriage. Lee gave the story a new spin by setting it in a Peranakan household with baba and nonya stereotypes. The production marked Lee’s first attempt at connecting with his Singaporean roots.

The Rebel with a Cause

In his own way, Lee was a rebel. Being the only pianist in his secondary school cohort at St Joseph’s Institution, he was often asked to play the rock organ and perform hits from heavy metal rock bands such as Black Sabbath and Grand Funk Railroad at school concerts. Like the other rockers of his time, Lee wore his hair long, yet was ever vigilant of the authorities who sometimes mistakenly nabbed hapless misfits whose only crime was that of trying to look cool. This was because in 1959, the government had launched a campaign to clamp down on negative aspects of Western popular culture that were perceived as decadent. The ban against the so-called “yellow culture”2 included pornographic publications and films, drugs, gambling, and even rock ‘n’ roll music and men with long hair; this policy did not ease until the early 1980s.

Against the backdrop of this campaign, Lee once had a close shave with the police. One evening while loitering in town, Lee and his friends spotted a police patrol car and decided to make a run for it because they thought they would be picked up for sporting long hair. While making his getaway in his red-and-black four-inch platform shoes, Lee lost his balance and tumbled into a ditch, fortuitously removing himself from view as his friends were caught by the police and sent to “haircut hell”.

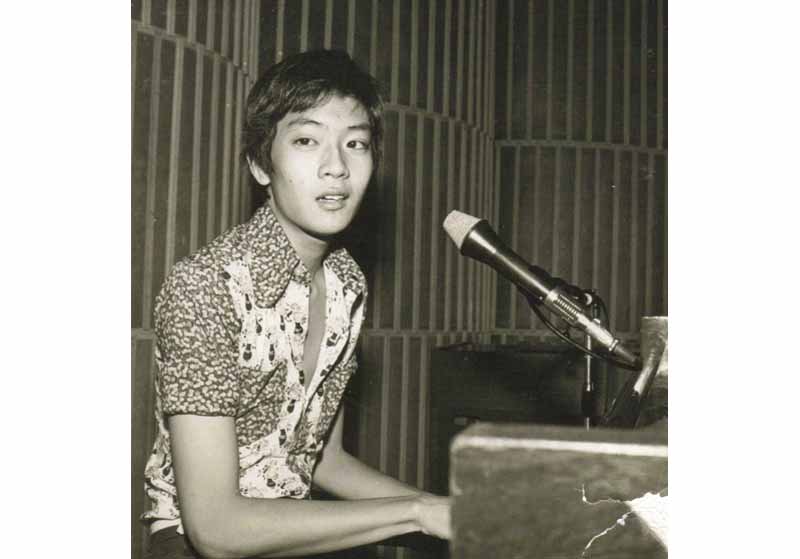

Dick Lee performing at Rediffusion's singing contest Ready, Steady, Folk in 1973. Courtesy of Dick Lee.

Dick Lee performing at Rediffusion's singing contest Ready, Steady, Folk in 1973. Courtesy of Dick Lee.

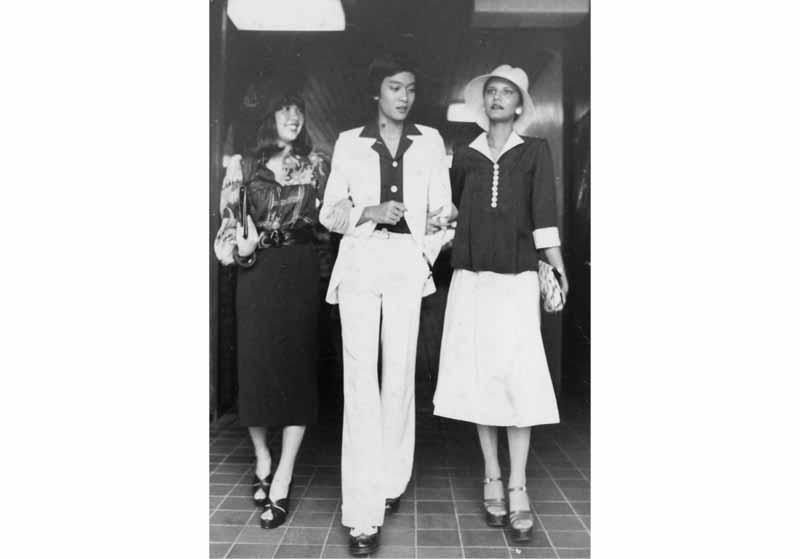

Dick Lee modelling his designs for his mother's boutique Midteen located in Tanglin Shopping Centre, with Tina Tan (left) and Sabrina Fernando, 1974. Courtesy of Dick Lee.

Dick Lee modelling his designs for his mother's boutique Midteen located in Tanglin Shopping Centre, with Tina Tan (left) and Sabrina Fernando, 1974. Courtesy of Dick Lee.

Album cover of music from Fried Rice Paradise, staged by Singapore Repertory Theatre in 2010. © Singapore Repertory Theatre, Singapore, 2010.

Album cover of music from Fried Rice Paradise, staged by Singapore Repertory Theatre in 2010. © Singapore Repertory Theatre, Singapore, 2010.

The Beginning

Lee’s music career took off while he was still a student at St Joseph’s Institution in the 1970s. He shot to mini stardom, thanks to his many stage appearances on talent shows and television programmes with the groups Harmony, and Dick and the Gang, the latter a musical group formed with his siblings.

In 1972, Lee auditioned for Ready Steady Folk, a talent show on television that was produced by cable radio station Rediffusion Singapore,3 and helmed by the legendary Vernon Cornelius of the band The Quests. During the audition, Lee performed “Life Story”, a song about a young man’s reflection on his life. This pivotal song helped to launch Lee’s music career, and became a familiar tune to many Singaporeans when it was used in a commercial years later.

“Wake up,” she said, “Look, it’s a beautiful day”

Downstairs to the kitchen door and then away

Into the light

Morning feeling lives on

Come the clouds the moon, and morning is gone

Just my life story

Minute by second a story

That goes on forever with each breath that I take

This is my life story

Uneventfullest story

That ages with each year and birthday cake

Lee was immediately offered a position on the show as a guest artiste instead of a contestant, giving him the chance to sing his original songs on live television every week. During the finals of Ready Steady Folk, he sang his now iconic “Fried Rice Paradise”, which so impressed one of the judges that Lee was offered a recording deal immediately. Lee’s first album, Life Story, was released in mid-1974 by the music label Philips.

His First Album

Not unexpectedly, record sales of Life Story were poor. The album only managed to sell a few hundred copies in Singapore and a much lower number in Australia, where his then manager had gone in an attempt to further Lee’s career. Poor reviews did not help the situation. One needs to keep in mind the context of the local music industry back then. The anti-yellow culture clamp-down in Singapore had left in its wake a moribund music scene. The recording industry in the 1970s was no longer as vibrant as it was in the roaring 60s, which saw local bands like The Quests and The Crescendos holding concerts and releasing records with the vociferous support of legions of fans. By 1973, what little interest that remained in local acts soon dwindled to a mere trickle.

On top of the unsupportive environment, a track on the album, “Fried Rice Paradise”, was banned from the airwaves by the government-controlled Radio Television Singapore (RTS) because of its flagrant use of Singlish. It is believed to be the first local pop song to be banned. To add further insult, the ban was not reported in the news as the media was not supportive of local music at the time. “I remember seeing a copy in their [RTS] library later. A couple of tracks were visibly scratched to prevent rebellious deejays from playing them,” Lee recalls.

Nonetheless, the song “Fried Rice Paradise” received substantial airtime on Rediffusion and became an instant hit. The endearing song is one of Lee’s most well-known, and was made into a musical in 1991.

Finally Making Tracks

Throughout the 1970s and 80s, Lee championed the use of Asian influences in local pop music and worked tirelessly to inject a strong Singaporean identity into his works. It was not until the mid-1980s when Singapore’s music scene was finally making some headway that Lee launched what has been deemed as his breakout pioneering album.

Ever the die-hard local boy, he says, “The term ‘Singaporean’ had no meaning at the time, so who was I – Chinese, Singaporean, Asian, English-educated, Peranakan? – and what did I have to say? I wanted not to be shallow, I wanted to be taken seriously. How could I introduce a Singapore element into a form that was basically Western? I wanted to do it with honesty, tapping on the things I knew.”

Wanting to write a song with commercial appeal that would also express how he felt about being a Singaporean, Lee penned “Life in the Lion City”, which became the title track of his album, released by WEA Records in 1984. The song described his life and its ups and downs in a light-hearted and upbeat manner.

The scene that he faces each morning

A tableau of buses and cars.

Then it suddenly rains without warning.

Then every destination becomes very far.

On some lucky days there are taxis.

But of course he’ll be stuck in a jam

Well, he can’t complain cause the fact is

He’s got the situation firmly by hand.

Driving past all the cinemas and shopping

centres lining the boulevards,

he contemplates then decides it’s

great here in Singapore, Singapore

So convenient tropical some more

Singapore, Singapore

Full of tourists and department stores.

He works very hard for a living.

Rewards are a holiday or two.

But he has to be calm and forgiving

Because his work environment is not very good.

The track “Culture” was also another attempt to instil a sense of the Singaporean identity into the nation’s collective consciousness. It was partly inspired by his reaction towards the government for trying to force-feed culture to the masses in its bid to achieve developed city status. Lee believed these efforts were futile because “suddenly having lots of ‘cultural’ events would not a cultured Singaporean make”.

One of the more significant tracks on Life in the Lion City is “Flower Drum Song”. Lee used the refrain from the popular Chinese folk song of the same name and incorporated it with his original melodies. It was his first attempt at fusion, way before the word became fashionable and meant an amalgamation of East and West. The song was a breath of fresh air in an era where singing Top 40 Western covers were de rigueur in the Singapore recording scene.

Even the album cover is distinctly local. It shows Lee surrounded by an eclectic mix of familiar Singapore symbols such as the Merlion, the national flower Vanda Miss Joaquim and the lower edge of what appears to be portraits of the president and first lady of Singapore of the time.

Although Life in the Lion City was released in 1984 with little fanfare, one individual who appreciated Lee’s music enough to turn it into a television show was the Singapore Broadcasting Corporation’s (SBC) producer, Lim Sek. He later became Lee’s business partner when they set up Music & Movement to manage the latter’s career when he went fulltime.

Album cover of The Mad Chinaman, Dick Lee's ultimate Singaporean album of ethnic pop. © Warner Music, Singapore, 1989.

Album cover of The Mad Chinaman, Dick Lee's ultimate Singaporean album of ethnic pop. © Warner Music, Singapore, 1989.

Hitting the Home Run

Lee’s tenacity in pushing for a Singaporean identity finally paid off in 1989 with the release of The Mad Chinaman album by Warner Music. One of the reasons for the success of this album was that it dovetailed with the national songs campaign that had been launched by the government in the 1980s. Community singing was advocated as a means for Singaporeans to develop a sense of belonging to the nation and foster solidarity among citizens.

Many of the catchy songs commissioned for the campaign and timed to be released for National Day – including “Stand Up for Singapore” (1984), “Count on Me, Singapore”(1986) and “We are Singapore” (1987) – struck a chord with people. The ground was receptive when The Mad Chinaman was released and Lee found a new audience that happily embraced his work. The Mad Chinaman featured songs that were inspired by Lee’s environment and his musical roots, and critics regard this as the ultimate Singaporean album of ethnic pop.

While the title track, “The Mad Chinaman”, was inspired by the Tiananmen Square massacre of 1989, Lee was moved to explore his Singaporean roots, acknowledging his confused identity in the lyrics of the song.

The Mad Chinaman relies

On the east and west sides of his life

The Mad Chinaman will try

To find out which is right

I know you can get confused

I get that way a little too

When the legacy of old surfaces as new

Traditional, International

Western feelings from my oriental heart

How am I to know, how should I react?

Defend with Asian pride? Or attack!

Lee also put humour to good use in his music. He chose the most popular Malay folk song he knew, “Rasa Sayang”, and added contemporary rap lyrics that told the story of Singapore in tongue-in-cheek fashion.

Not one to fear controversy, Lee included another satirical song in the album, bravely taking an open dig at the ongoing Speak Mandarin Campaign. The song described a Chinese “lesson” which had Lee repeating some Mandarin phrases after the teacher as well as children reciting Mandarin verses in the background.

The Mad Chinaman record became such a hit that it went platinum within four months of its release, and won awards in Singapore, Hong Kong and Japan. Lee achieved regional prominence following the album’s phenomenal success, and he toured Japan, Hong Kong, Seoul and Taipei to adoring crowds. The “Mad Chinaman” moniker has been synonymous with Lee ever since.

However, it was not all smooth sailing. In Singapore, “Rasa Sayang” was initially banned from the radio as the government had deemed the use of Singlish in the rap as undesirable. The controversy made the headlines. After several public debates on the differences between bad English and Singlish, the authorities finally softened their stand and accepted the value of the average Singaporean’s “natural way of speaking English” as Lee describes in his biography. After a few weeks, the SBC relented and the song received massive airtime over the radio.

Lee was proud of who he was: “Singlish was part of who we were. It made us unique. Singaporeans who spoke perfect English all spoke Singlish to each other. Even foreigners living in Singapore said ‘lah’.”

In 1990, Lee relocated to Japan to further his music career. He continued to develop the Asian identity through his works, and through collaborations with famous Asian artistes such as Sandy Lam, Anita Mui, Andy Lau, Aaron Kwok and Miyazawa Kazufumi. For his efforts, Lee was rewarded with two Hong Kong Film Academy Awards – a feat no other Singaporean has ever achieved. The first, awarded in 1995, was for Best Original Movie Theme Song for She’s a Man, He’s a Woman. Four years later in 1999, he bagged the same award for the film City of Glass.

Lee’s work in the Land of the Rising Sun proved instrumental in opening Japanese eyes to Southeast Asia. Soon, magazines were featuring stories on Singapore, and Lee’s name was always mentioned alongside. The publicity and attention lavished on Lee indirectly brought fame to his homeland, and Singapore became more than just a little red dot famous for its sarong kebaya-clad “Singapore Girl”. Singapore suddenly became an exciting new travel destination for the Japanese – one that had produced the enigmatic “Mad Chinaman”.

Beauty World Cha-Cha-Cha

Lee’s passion for musicals led him along a different yet complementary path. He has written several groundbreaking musicals, including Fried Rice Paradise (1991) Kampong Amber (1994), Sing to the Dawn (1996) and Hotpants (1997). The epic Nagraland toured Japan, Singapore and Hong Kong in a 2002 sold-out tour, and Snow.Wolf. Lake, which starred Hong Kong pop star Jacky Cheung, toured several Asian cities in 2005. Among his famed musicals, the most well-known was the first one he produced in 1988, the all-time favourite Beauty World.

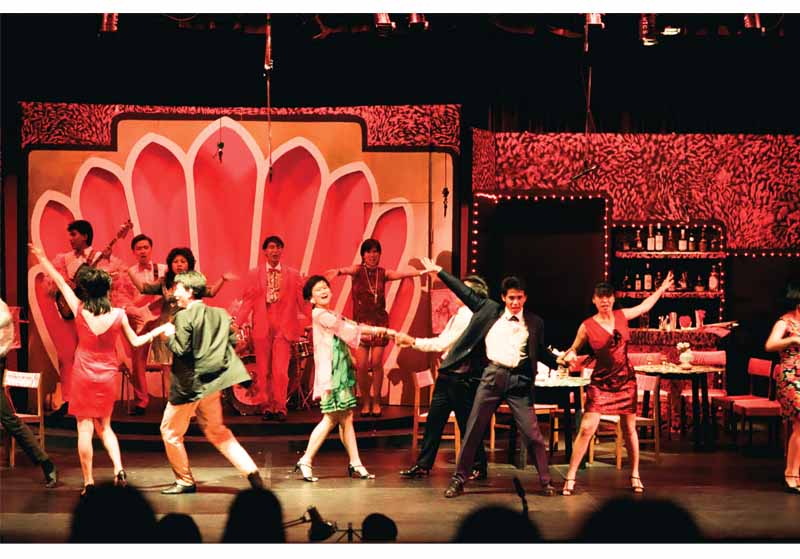

A TheatreWorks production of Beauty World directed by Ong Keng Sen. It was first staged by TheatreWorks in 1988 and toured Japan in 1992, followed by a re-staging for the President's Star Charity in 1998. Courtesy of TheatreWorks (S) Ltd.

A TheatreWorks production of Beauty World directed by Ong Keng Sen. It was first staged by TheatreWorks in 1988 and toured Japan in 1992, followed by a re-staging for the President's Star Charity in 1998. Courtesy of TheatreWorks (S) Ltd.

An iconic musical well-loved by many Singaporeans, Beauty World was named after a covered market at the junction of Upper Bukit Timah Road and Jalan Jurong Kechil. Among the hodgepodge cluster of textile and household shops were a couple of music shops selling cassettes and records. This was where Lee had his first taste of music heaven and discovered that local musicians also cut records. Before long Rita Chao, Sakura Teng, and Naomi and the Boys had all become part of Lee’s collection of singles at the tender age of 11. Little did he know at the time that this discovery would eventually come full circle and give birth to the psychedelic musical called Beauty World.

Several years later, as Lee grew increasingly successful in his career in the fashion industry, he met and collaborated with Linda Teo, who eventually became his business partner at Runway Productions, a fashion show production company. Linda’s humble beginnings as a factory worker and her success story as the owner of top modelling agency Carrie Models, bore similarities to Lee’s own mother’s life. Lee was inspired to write a musical based on both women. The prodigious talent that he is, Lee playfully tinkled on the piano one evening in 1986 and wrote “Beauty World (Cha-Cha-Cha)” in just five minutes. “I certainly achieved my goal in creating a happy song, as I could not stop singing it,” he remembers.

Thus began the journey of Singapore’s very first homegrown musical, Beauty World. The musical tells the story of Ivy Chan Poh Choo, a young and guileless small-town girl from Batu Pahat who enters the seedy cabaret world in search of her long-lost father. It was first staged by TheatreWorks in 1988 to critical acclaim. Beauty World’s week-long opening run was sold out and prompted the production team to bring it back two months later, where it enjoyed another sold-out run. This was unprecedented in Singapore theatre history. The musical has since been performed several times: in 1992 when it toured Japan; in 1998 when it was produced by MediaCorp for the President’s Star Charity show; and in 2008 when it was staged by theatre company W!ld Rice, which added new scenes and songs to the musical.

Lee says of the musical: “These days, I feel a flush of pride when young actors come up to me and say that Beauty World inspired them to do theatre, or that it was the first musical they had ever seen.”

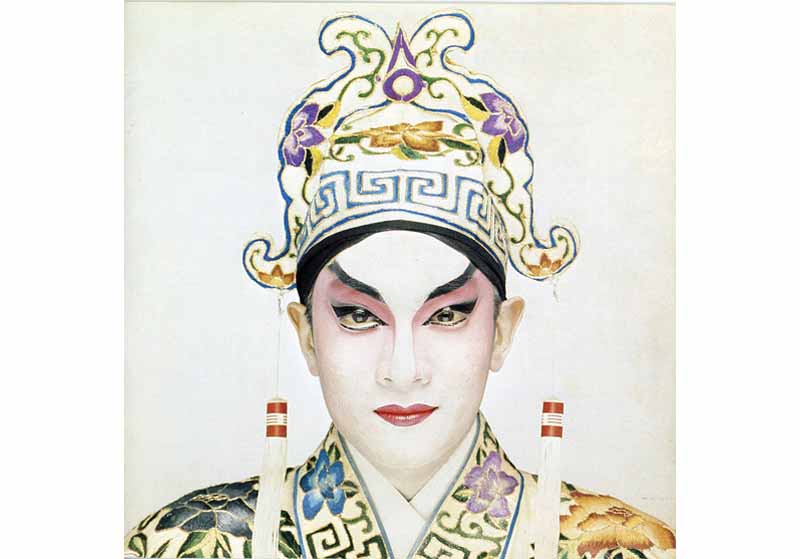

Forbidden City: Portrait of an Empress

Not one to sit idle, in the new millennium, Lee again pushed the boundaries, this time taking a leaf out of Chinese history by challenging commonly held notions of Cixi, the last empress dowager of China.

Lee was intrigued by the story of Cixi and rabidly researched her life and history, especially the challenges she must have faced as the ruler of China in the final years of the Qing Dynasty in the early 1900s. Not content to believe the popular accounts of Cixi as the infamous power-crazed despot, Lee wanted to explore a different side of her – as a woman, mother, wife and lover.

In 2002, Lee travelled to London with lyricist Stephen Clark and director Steven Dexter to work on an outline for a musical on Cixi’s life. The trio visited the British Library to study out-of-print books on Cixi and stumbled upon an important work on the empress dowager by American artist Katherine Carl, who painted Cixi in her first Western-style portrait.

A scene from the musical Forbidden City: Portrait of an Empress, with Kit Chan (centre, in red costume) playing the lead role. Dick Lee wrote the music for this Singapore Repertory Theatre (SRT) production that was first staged in 2002. Courtesy of Singapore Repertory Theatre.

A scene from the musical Forbidden City: Portrait of an Empress, with Kit Chan (centre, in red costume) playing the lead role. Dick Lee wrote the music for this Singapore Repertory Theatre (SRT) production that was first staged in 2002. Courtesy of Singapore Repertory Theatre.

Carl had been sent to the Forbidden City in 1903 to paint the empress dowager in just three days, but was so well-liked by the empress that she stayed for more than six months. Her account, With the Empress Dowager, published in 1905, had been written partly in defence of the scandalous books that were being published on the empress at the time, some of these attributing fictitious quotes to Carl herself.

Thus, the musical Forbidden City: Portrait of an Empress was born, starring Singapore singer Kit Chan in the titular role. Forbidden City was one of the highlights of the opening festival of Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay in October 2002. Owing to its immense popularity, the production returned for two re-runs in 2003 and 2006. Lee’s compositions for the musical subsequently went on to win the Life! Theatre Awards for Best Music in 2004.

The Consummate Performer

“Dick Lee’s talents defy categorisation. If you think that his life is as colourful as the characters in his musicals and songs, then you are wrong! It is ten times more exciting and dramatic.”

A stalwart in the popular cultural history of Singapore, Lee continues to be a mover and shaker as he continues his “mad” adventures in music and theatre, embracing life as few people do.

In 2014, Lee celebrated his 40th anniversary in show business with a concert titled DL40; it was a sold-out ride down memory lane. Lee performed many of his earlier hits, including “Internationaland”, “Follow Your Heart”, “Thanksgiving”, “Singapore Nights” and more recent ones like “Treasure Every Moment”. At the end of the show, Lee paid a special tribute to Vernon Cornelius, the man who gave him his first break back in 1972.

As Singapore celebrates her golden jubilee this year, Singaporeans can look forward to more of the “Mad Chinaman” and his works. Lee will be performing a medley of his songs at the mega Sing50 concert at the Singapore Sports Hub on 7 August in celebration of Singapore music. He is the creative director for this year’s National Day parade, and has also composed the parade’s theme song “Our Singapore”, which he will sing at the event with Mandopop star JJ Lin. This is not Lee’s first attempt at penning a National Day song. In 1998, his song “Home” composed for the Sing Singapore festival was selected as the theme song for the National Day parade that year. The heartwarming song became popular with Singaporeans and a remixed version was used as the theme song for the 2004 edition of the parade.

Ever the consummate performer and entertainer, Lee will not be resting on his laurels anytime soon and likely has more ideas up his sleeves. We say bring on more of the music, madness and magic.

Joy Loh is a Performing Arts Librarian with the National Library of Singapore. Apart from managing the National Library’s digital music archive, MusicSG, she enjoys reading as well as learning new musical instruments and languages.

REFERENCES

Brazil, D. (1989, November 19). This is S’pore. Sharp. Hip. You’ll like it, donch worry! The Straits Times, p. 32. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Carl, K.A. (1905). With the Empress Dowager of China. New York; The Century Co. Retrieved from World ebook Library.

Chow, C. (2002, July 31). Eat forbidden fruit. The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Chow, J. (2014, August 11). Dick Lee to write ‘the next Home’ for S’pore’s 50th NDP. The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Chow, J. (2015, May 8). JJ Lin will join Dick Lee to sing Our Singapore. The Straits Times, pp. 2–3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Lee, D. (2015). News updates. Retrieved from Dick Lee website.

Dick Lee wows ‘em. (1990, August 26). The Straits Times, p. 19. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Gwee, E. (1998, June 20). Roomful of me, here and there. The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Gwee, E. (1998, June 20). Here’s my Life Story. The Straits Times, p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Ida Bachtiar. (1989 November 23). A Singapop breakthrough? The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Island asylum for Mad Chinaman. (1989, September 22). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Kids to star in this year’s NDP finale. (2004, July 6). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Lee, D. (2011). The adventures of the mad Chinaman. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions. (Call no.: RSING 782.14092 LEE)

Low, J. (1975, March 16). No major change in Status Quo music. The Straits Times, p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Tan, J.H.S. (2011). Lee Kip Lin. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia, National Library Singapore.

National Library Board. (2014). Campaign against yellow culture is launched. Retrieved from HistorySG website.

Ho, S. (2015, March 11). National Day songs. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia, National Library Singapore.

Oon, V. (1974, December 26). Dick tells his life story on disc. New Nation, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Ong, S.C. (1990, March 25). Japanese bowled over by ‘Mad Chinaman’ Dick Lee. The Straits Times, p. 21. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Perera, L.M., & Perera, A. (2010). Dick Lee (李迪文): Creating endless opportunities. Retrieved from MusicSG.

Singapore Repertory Theatre (n.d.). About forbidden city. Retrieved from Singapore Repertory Theatre website.

Tan, J. (2007, September 7). A new beauty. Today, p. 58. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

The origins of keroncong. (1993, November 12). The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewpaperSG.

What is a Singapore song? (1989, August 6). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Wong, J. (1989, December 3). Can Singapop storm the world? The Straits Times, p. 20. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Yong, S.F. (1998, March 28). Home again. The New Paper, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

NOTES

-

Also spelled keronchong and kronchong, keroncong refers to a type of ukulele-like instrument as well as to the Indonesian musical style that makes use of this instrument. The music has its origins in the 16th-century music of the Portuguese colonies in Batavia and the Moluccas. ↩

-

On 8 June 1959, the government, led by the newly elected People’s Action Party (PAP), launched a campaign against yellow culture. The term “yellow culture” is a direct translation of the Chinese phrase huangse wenhua, which refers to decadent behaviour such as gambling, opium-smoking, pornography, prostitution, corruption and nepotism that plagued much of China in the 19th century. ↩

-

Rediffusion was Singapore’s first cable-transmitted, commercial radio station. It started broadcasting in Singapore 1949. ↩