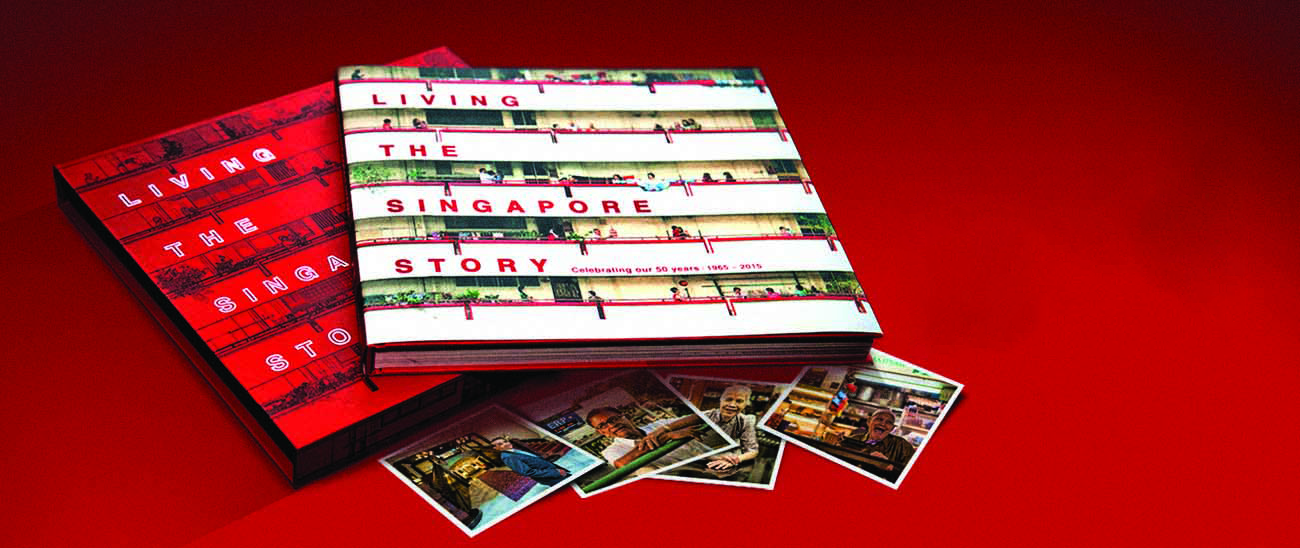

Stories We Can Call Our Own

Han Fook Kwang shares some of his favourite stories from Singaporeans as told in Living The Singapore Story, a book commemorating the nation’s golden jubilee.

What is the Singapore Story?

The answer is not straightforward because different people will have different views of what story they most identify with this country. For some, it might be founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew’s memoirs. That story though is told from his point of view even if he had the advantage of being at the centre of many of the country’s most dramatic political events. What of the many other people who might have seen the story differently or have other stories to tell? Do their accounts matter and have a place in the nation’s storytelling?

When a group of us at The Straits Times were tasked with writing a book to commemorate Singapore’s 50th anniversary, we spent much time debating this point.

How do you capture the story of this nation, its achievements and disappointments, the ups and downs, the personal glories and tragedies that are part of any society’s history? How do you make sure the story is not one-dimensional but multi-colour and flavourful?

If we had told it the usual way, starting with the political battles with Malaysia, then separation, and the years of nation-building and economic development, we feared it would be an overly familiar story. It would probably also have to be told from the top down, with the leadership taking the limelight.

We decided instead to do it through the stories of ordinary Singaporeans who, through the lives they led and the things they did, told the Singapore story as much as the historical accounts.

It turned out to be a deeply satisfying project because we found a treasure trove of stories, which is not surprising because Singapore has been a very happening place these past 50 years. It is not a dull place which stays put.

In all, we found 58 storytellers from taxi driver to bus captain, teacher, satay man, doctor, scientist, soldier, policeman, athlete, mountain climber, civil servants and many more.

Here are some of my favourites in the book, Living The Singapore Story, which was launched on 15 May 2015.

Kopitiam boss Lim Bee Huat started work cleaning tables at coffee shops for $1 a night. He was so poor he used to eat the food left by people at roadside offerings during the Hungry Ghost Festival. But he worked his way up, starting his first stall at the old Esplanade ground. Today, he owns more than 80 outlets and his staff get a Rolex watch from him when they have worked for more than 10 years.

There is a veteran unionist, Abdul Rahman Mahbob, who, when he was just starting work in 1966 at the Pasir Panjang power station, saw his fellow workers going on strike for higher pay. He was not part of the strike then but he was so moved by their dedication and courage, he decided to join the union and rose to become president of the Union of Power and Gas Employees. He has seen grown men cry when told they were being retrenched and he recounted how he saved one worker by going directly to the big boss.

Another veteran – policeman Rahman Khan – was shot by Singapore’s most famous cop killer, Botak. But the assignment he remembers most vividly to this day was the gruesome body count he had to do after the Greek tanker Spyros exploded at Jurong Shipyard, killing 76 workers.

Angel Ng was an angry young woman who was jailed eight times for various drug offences. When she last left her cell, she got a job at a call centre started by the prison authorities under its Yellow Ribbon project. Today, she manages three call centres.

Adam Maniam is a Tamil-Eurasian-Malay-Pakistani lawyer with a Catholic Tamil grandfather and a Eurasian grandmother. His father married a Muslim woman and converted to Islam. The lawyer married a Chinese girl and they decided on a civil marriage. It is a complicated story but very Singaporean.

There are also some not-so-ordinary people in the book.

Lee Khoon Choy was ambassador to Indonesia from 1970 to 1974. It was a tough assignment as Singapore had, in 1968, hanged two Indonesian marines for planting a bomb at MacDonald House which killed three persons. Lee related how a man came to his house in Jakarta and threatened him over what Singapore did.

When Lee asked for a bodyguard, he was told bluntly by then Foreign Minister S. Rajaratnam: “We are a small country. We cannot afford that.”

When J.Y. Pillay started Singapore Airlines, he was told by the Government: “Make it work and don’t come back to us for more money. You either survive on your own or fold up.” We know which option he chose.

These stories, whether of ordinary people or well known ones, help us better understand the Singapore we call home. Every nation must have these shared memories which the people can identify with and call their own. They strengthen the sense of belonging and identity, often more powerfully than physical landmarks or buildings.

Sometimes, these stories of the past provide comfort and satisfaction: See how far we’ve come! At other times, they give us greater confidence in the future: That’s how it was done before! Whatever they do to you, they are a precious part of who we are. This is especially important in Singapore which is changing so rapidly, making one generation so different from the next.

Many Singaporeans get upset when old landmarks and places they remember fondly from their childhood are torn down or replaced by new structures. They feel a deep sense of loss to the emotional connection they have with the past. It’s the same with these stories.

If we do not find a way of recording and remembering them, it will be like those forgotten buildings, lost forever.

Adam Maniam (standing, left), with wife Yap Cuixian and their daughter Amelia Ri-En, his elder brother Aaron (seated, top) and younger brother Ashraf, together with his father Sydney (right), mother Bibe Zoolaha and maternal great-grandmother Chan Bibi. Adam is a Tamil-Eurasian-Malay-Pakistani lawyer with a Catholic Tamil grandfather and a Eurasian grandmother.

Adam Maniam (standing, left), with wife Yap Cuixian and their daughter Amelia Ri-En, his elder brother Aaron (seated, top) and younger brother Ashraf, together with his father Sydney (right), mother Bibe Zoolaha and maternal great-grandmother Chan Bibi. Adam is a Tamil-Eurasian-Malay-Pakistani lawyer with a Catholic Tamil grandfather and a Eurasian grandmother.

From Drug Offender to Call Centre Manager

Angel Ng, 50, was in and out of jail for drug offences between 1982 and 2008. She now manages three call centres which hire ex-offenders.

Being in and out of jail so many times since I was 17 did not scare me off prison life. Being in prison was no big deal; some prisoners wanted to return to prison because they found that better than having to face society.

In 1994, two weeks after I gave birth to my only child, Valerie, I was jailed yet again. I’m aggressive and argumentative by nature and I always had the spirit of buay sai see (must not die in Hokkien).

But this time, I had post-natal depression, missed my baby and was worried about how my mother, who’d just been told she had cervical cancer, would cope with bringing up Valerie. I thought: “I’ve been such a burden to my mother, and I can’t change. It’s best to end it all.” I took a metal spike from the toilet brush and cut my wrists… The wardens saved me.

But I was still not motivated to change my ways. I just wanted to damage myself completely because I had a deep anger against the world for being unwanted at birth. While in prison, at the age of 33, I studied for the O levels and scored five straight A1s in subjects like English literature and history.

In 2003, when I was 38 and had started serving my longest-ever prison sentence – 8½ years, later reduced to six years – I began reading books on religion and philosophy from the prison library. Age was catching up with me. I thought: “I can’t keep living like this.”

The following year, I learnt that the prison authorities were starting Southeast Asia’s first prison call centre, as part of the Yellow Ribbon Project that had just been set up to help ex-offenders find jobs to re-integrate into society. I wanted to work there because it was a white-collar job for which I had to use only my voice, and not my appearance. So I’d be able to work till I was very old.

I was released from my last prison term on 11 November 2008. A week later, I began working at call centre Connect Centre’s headquarters. It’s been a big learning experience and it has taken me to new places.

Most newly released ex-offenders have no money, so Connect gives them $10 a day for meals until they get their first month’s pay of about $1,000. They need to stay focused by holding a steady job because that disciplines and stabilises them.

Angel Ng oversees more than 50 employees, many of them ex-offenders, at Connect Centre. It trains former inmates at its three call centres so they have a chance at holding down steady jobs and re-integrating into society.

Angel Ng oversees more than 50 employees, many of them ex-offenders, at Connect Centre. It trains former inmates at its three call centres so they have a chance at holding down steady jobs and re-integrating into society.

Made in Singapore: Asia’s First Test-tube Baby

Despite his unusual beginnings, Samuel Lee, 32, says he’s just an average Singaporean.

My friends used to tease me when we were children: “You’re man-made!” I would laugh it off, but when I think about it, they were right.

I was the first test-tube baby born in Asia on 19 May 1983. My father was 21 and my mother 19 when they married in 1976. They tried to conceive, but with no luck until 1982, when they took part in a clinical trial under Professor S. S. Ratnam and Professor Ng Soon Chye. Although doctors implanted embryos in eight women, I was the only success.

I was born to great media attention, which made my parents uncomfortable. We were ordinary Singaporeans living in a three-room flat in Woodlands. My father was a security supervisor and my mother a secretary. Thankfully, the in-vitro fertilisation (IVF) was subsidised, and thus affordable for them.

My birth might have been considered extraordinary, but I was raised like any ordinary Singaporean. I got my first inkling that I was somehow different from other kids when I heard other people referring to me as a test-tube baby when I was four or five. I asked my parents about it, and they just gave me a simple explanation of how I came about. I used to ask my parents for a sibling. They’d laugh and tell me it was a very difficult request to fulfil. It was only when I was older – around 13 – that I understood why and realised what my birth really meant.

The late Prof Ratnam gave me the name Samuel. I don’t know why. We did not really stay in touch after my birth. But I do e-mail and text Prof Ng occasionally. Without them, there wouldn’t have been me.

You could call me an advocate of IVF. I often encourage my friends who are trying to conceive to go for it. I love kids and would definitely want my own. But first, I have to find myself a girlfriend.

Samuel Lee with a projection of a newspaper article marking his birth. He says that, fanfare aside, he grew up an ordinary Singaporean, in a three-room flat in Woodlands, with parents who refused to pamper him with too many toys.

Samuel Lee with a projection of a newspaper article marking his birth. He says that, fanfare aside, he grew up an ordinary Singaporean, in a three-room flat in Woodlands, with parents who refused to pamper him with too many toys.

The Day He Faced a Cop Killer

Abd Rahman Khan Gulap Khan, 65, spent 35 years in the police force – most of them in the Criminal Investigation Department.

The worst pain I ever felt in my life was on the night that I got shot. Not from the bullet, but from the tetanus jab I had to get later in the hospital. I couldn’t sleep on my buttocks for three days.

I was shot by this guy we called the “Cop Killer” in 1973. He shot and killed a detective over a minor traffic accident and the whole police force was searching for him. The breakthrough came from a robber who told us that among the most notorious robbers at that time, the one most likely to engage with police was this man known as Botak.

We managed to trace him to Cavenagh Road Apartments and used a ruse to get him out. When he came running out, a colleague put him in a headlock, but Botak had already pulled out a gun. I grabbed hold of the gun, a stolen police revolver, and he fired two rounds which burned my palm. A third shot grazed my stomach. We couldn’t subdue him, so my colleague shot him twice in the arm, but Botak still wouldn’t drop his weapon. Then other colleagues rushed in, and one fired a shot that I felt go past my ear, which hit Botak in the head.

Then there was the disaster in 1978, when the Greek tanker Spyros exploded at Jurong Shipyard. We spent one solid week in the mortuary, which had only a few refrigerated compartments in which to keep bodies. But we had 76 bodies, and had to leave them lying around on the floor to decompose.

I remember we were eating nasi briyani at an operating table with bodies on the floor. We had to take our food there as we couldn’t leave, as we were waiting for people to come in to identify the bodies, and every hour the body changes because of decomposition. After that, I had to throw away all the clothes I was wearing, including my undergarments, shoes, everything, because it all stank. Even a few days after we were done, when I sat in the bus, people were still holding their noses, because the smell sticks to your skin. You bathe with Dettol, you wash your hair, the stink is still there.

Veteran police officer Abd Rahman Khan Gulap Khan was at the front line of several major investigations.

Veteran police officer Abd Rahman Khan Gulap Khan was at the front line of several major investigations.

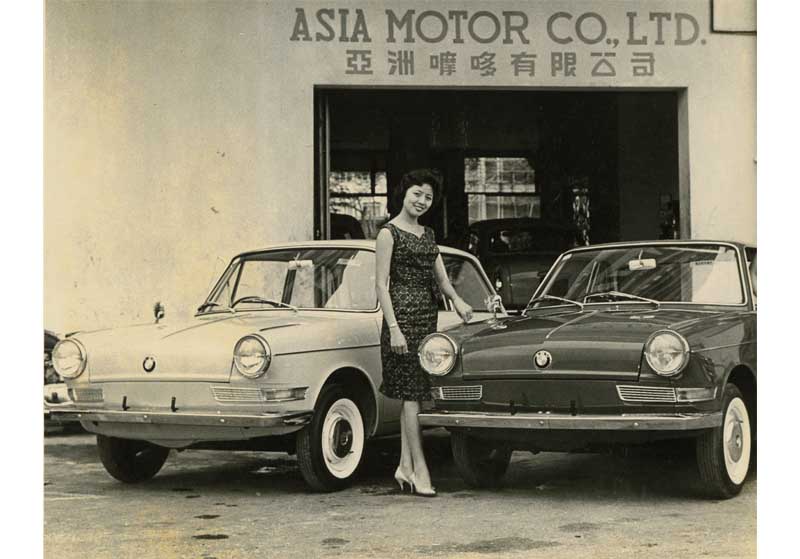

I Sold Cars to Presidents

Singapore’s first car saleswoman Rosie Ang, 77, took on a man’s job and stayed 53 years.

President Benjamin Sheares summoned me to the Istana after my boss sold him a car in the early 1970s. He said: “Rosie, you tell your boss to please rectify the problem because the car keeps stalling.” But I didn’t mind being scolded because I got to see his office at the Istana – so nice!

Mr Sheares was not the only president I met in my career. Asia Motor, which I joined in 1958, also sold a Peugeot to our first president, Yusof Ishak. I delivered the car to him at the Istana too.

When I left school, I saw an advertisement for a sales representative at Asia Motor. I was 20 then and already into cars. I had passed my driving test the year before. The person who interviewed me asked if I knew about car engines. I said: “If you give me a chance, I can learn. I also love to meet people, I love to talk, I like to move around, and I drive.” I got the job.

My colleagues, all men, were sceptical. After all, I was the first woman car sales rep in Singapore. They were polite but didn’t really teach me how to sell. Since I was new and didn’t have my own pool of customers, I couldn’t sit in the showroom and wait for people to come. So I went out to canvass for sales in the diesel Peugeot 403 that the company provided. In my high heels – never court shoes – I drove everywhere, even to muddy areas in Jurong.

My basic pay was $150 a month. It was OK, because back then $500 could feed a family. My days were long, but my hard work paid off. Being a woman also helped, as some customers may have pitied me. My average (sales) were four new cars and four used cars a month, which compared favourably with my colleagues.

In 1964, we brought in Mazda, but people didn’t trust a Japanese make. They would say, “That’s just a Milo tin.” But the car proved to be reliable and sales soared. I once sold 20 cars at one time to a customer and his friends.

I still love cars and will spend more than an hour washing my daughter’s car. The only part I don’t clean is the engine – I don’t want to dirty my nails!

Rosie Ang at her company's car showroom at Ngee Ann City Building on Orchard Road in the 1960s. It was one of several showrooms in the area then. Courtesy of Rosie Ang.

Rosie Ang at her company's car showroom at Ngee Ann City Building on Orchard Road in the 1960s. It was one of several showrooms in the area then. Courtesy of Rosie Ang.

Veteran car saleswoman Rosie Ang, 77, started out in the business when she was 20. Her working hours were long, but her hard work paid off, and she had plenty of referrals. She even delivered a car to Singapore’s first president, Yusof Ishak.

Veteran car saleswoman Rosie Ang, 77, started out in the business when she was 20. Her working hours were long, but her hard work paid off, and she had plenty of referrals. She even delivered a car to Singapore’s first president, Yusof Ishak.A Voice for the Less Advantaged

Dr Kanwaljit Soin, 73, was the first woman Nominated MP and stood out not only for her suggestions but also for asking tough questions in Parliament.

When the papers reported in 1992 that the government was looking for a new batch of Nominated MPs, many people were excited. I was president of the Association of Women for Action and Research at that time, so I rang up a few women and said: “Please apply.” They all said no. I then decided I had no moral right to persuade them to do something I wasn’t doing myself. So I applied, even though I had no idea what a parliamentarian did.

When I met civil servants, they would tell me: “Do you know, every time you ask a question, it costs the civil service money? We have to do research to answer it.” But that meant I got a lot of statistics from the government, because it had to reply to me.

If there’s one thing Parliament taught me, it’s that if you want to be in any area of policymaking, it’s important to get the statistics right.

If the statistics are wrong, you get shot down and the rest of what you’re trying to say gets lost.

What I really consider my biggest achievement was moving the Family Violence Bill in 1995. Even though it was defeated then, many of its provisions were subsequently incorporated into the Women’s Charter.

Two things I suggested in Parliament have become a reality: I wanted an educational (Edusave) account set up for every adult Singaporean, and a medical savings account set up for every elderly Singaporean. So 20 years down the line, both my dreams have been fulfilled by the SkillsFuture Credit scheme and the Pioneer Generation Package.

When you look at society in general, business, government and civil society are the three legs of the stool, but it’s only recently that policymakers in Singapore have realised that it’s prudent to include civil society in decision-making. If the stakeholders are just business and government, they sometimes don’t see the point of view of the rest of society, especially the disadvantaged.

There are a lot of Singaporeans who haven’t done as well as the country’s indicators seem to suggest. They still need people to advocate for them, highlight their difficulties, and try to make it such that more people get a share of the pie.

I feel in particular for the elderly. They are poorer in general, and things like the Silver Support Scheme and the Pioneer Generation Package are just the beginning. We can still do better – we need to give them some autonomy and dignity. We retire way too early in Singapore. Even when I was in Parliament, we were talking about moving it up to 67. Why hasn’t it changed yet? Why is there even a retirement age at all? Older people have institutional memory, they have built networks and they are loyal to organisations.

People should be allowed to work for as long as they think they can, and as long as their employer finds them producing good work.

Singapore’s first woman Nominated MP Kanwaljit Soin says moving the Family Violence Bill in 1995 was her biggest achievement.

Singapore’s first woman Nominated MP Kanwaljit Soin says moving the Family Violence Bill in 1995 was her biggest achievement.

Do You Know the Satay Man? He’s Moved

Ngalirdjo Mungin, 94, started hawking satay on the streets. He moved to a stall in a food centre in the early 1970s, which is now operated by one of his sons.

The first food I started selling in 1945 was Indonesian kuih. That was all I knew how to make. But I wanted to sell satay – the problem was, I didn’t know how to make it. I was young and too scared to ask anyone, but I stayed in the Sultan Gate area with many other Javanese who sold satay so I would just stand near these other satay-sellers and memorise the ingredients. At first, I copied them, but after a while, I made changes. Many would use hammers to beat the meat to tenderise it, but I learnt to do everything by hand. It took hours to rub the marinade in, but I felt it was better.

Almost every evening, I would walk to Jalan Besar, where there was a football stadium. There were already four or five people selling satay there, and we all had our unofficial locations. I would go to the back entrance – everyone knew that belonged to me. Eventually, I also started selling satay near the Padang.

At one point, I tried to set up a stall under the Merdeka Bridge, but the Ministry of Health stopped me. I moved into this stall in Sims Place Food Centre in 1973, when the government started asking hawkers to move off the streets. I knew the man in charge of the Sims Place market, and he asked me to set up shop there. By then, everyone in the area knew me, so he convinced me to move there, to make it easier for people to come to one location. It was actually a blessing, because after I moved, I made a lot more. My earnings doubled, then tripled. I could afford to perform the Haj pilgrimage the first year.

I started selling less satay and more of other Malay food. My stall is named after my wife, Kamisah Dadi, who died in 2010. About 10 years ago, I passed the stall on to one of my sons. I’m willing to hand down my stall only to my own blood. This place is not about profit. I could easily have sold my dishes for a lot more, but I just looked at the price of meat and vegetables and priced my dishes according to that.

I still come in every day to my stall and eat a bowl of mee rebus or mee soto. This way I can ensure my son is doing a decent job, that the quality is still good.

At age 94, Ngalirdjo Mungin still goes to his stall, which his son runs now, to check if the quality of the mee rebus and mee soto is good.

At age 94, Ngalirdjo Mungin still goes to his stall, which his son runs now, to check if the quality of the mee rebus and mee soto is good.

Sometimes You Need More Than Prayers

After two heart attacks and more than 60 years as a nurse and mid-wife, Sister Thomasina Sewell, 81, still keeps patients company every day at the Assisi Hospital and Mount Alvernia Hospital.

The Assisi Hospice used to be a convent housing nuns, but we vacated it and refurbished it as a hospice for the terminally ill in 1992. The idea of nursing terminally ill patients is to give them quality of life. The way we care for them changes from how we do so in an acute hospital. We try to make the hospice home for such patients and their families, to help them come to terms with one another.

You cannot allow the sadness to get to you, otherwise you are of no help to patients. But people shouldn’t think they have to be trained before they can be with them. Your presence is important because often, their fear is loneliness and that nobody understands what they are going through. That’s why every room in the hospice has a sofa, to encourage family members of patients to stay overnight.

Once, while praying in the Mount Alvernia Hospital chapel, I saw this strapping man in a wheelchair who sobbed and sobbed. I put my hand on his, to let him know I felt for him. Later, I started talking to him in the hospice. He told me he was 40 years old, cycled to work daily and had never smoked or drunk alcohol. Now he had pancreatic cancer and was given three months to live. You can’t rely solely on prayer for patients like him. Life is more than prayer for them; it’s about helping them deal with the here and now. He and his wife were estranged, and they had a son and daughter aged 12 and 13.

Once, while I was talking to him, a friend of his came by and told him: “Oh, you’re going to get better and we’ll go cycling again.” I was so angry because that was not reality. But I didn’t say anything because it’s not for me to say anyone is right or wrong. After his friend left, we talked about reality. He was not bitter at all, but worried about his children as he and his wife weren’t close. I told him: “She’s still a good mother.” His wife turned up eventually and didn’t desert him. I put my arms around her to comfort her as she was very upset. I have not got used to losing a patient; how can you? Sometimes I’ll be choking back tears at the service but I try to calm myself so I’ll be helpful to the families.

Sister Thomasina Sewell is a nun in the Catholic order known as the Franciscan Missionaries of the Divine Motherhood. In 1961, she and 36 other nuns set up Mount Alvernia Hospital.

Sister Thomasina Sewell is a nun in the Catholic order known as the Franciscan Missionaries of the Divine Motherhood. In 1961, she and 36 other nuns set up Mount Alvernia Hospital.

My Son, the Award-winning Pathlight Artist

Sales engineer Kelvin Phua, 55, talks about his son Glenn, 19, who has autism and has been dubbed Singapore’s Stephen Wiltshire.

During Glenn’s school holidays in 2010, we found a note in his schoolbag about some art homework he had to submit. It had to be related to F1, and he drew eight cars coming around a race track. We didn’t pay much attention to it, except to say “good job”. We were just happy he had finished his homework.

A few months later, his school, Pathlight School, called and said: “Your son has won a big prize.” We had no idea what this was about, but took leave to attend the ceremony in Raffles Place. Only when we were there did we realise he had won first prize – a set of four F1 grandstand tickets and an opportunity for Glenn to sit in a real F1 car.

We discovered Glenn was autistic when he was four, when he had trouble making eye contact. He attended a mainstream primary school until halfway through Primary 2. We transferred him to Pathlight, which teaches a mainstream curriculum and life skills to children with autism.

After Glenn started attending Pathlight, I attended an anger management class that the school organised. I started trying some of the strategies, and also swapped notes with his teachers about what works for Glenn. We had a hard time with him, but children with autism are also the most loving.

We didn’t actually realise Glenn had this talent. When he was about eight or nine, he drew a lot of cartoons, copying characters from Peanuts or The Simpsons, and they were very good, but we didn’t think much of this, because all children doodle. But since Glenn won the F1 competition, he has drawn more than 150 pictures. He never sketches – he just puts pen to paper and draws.

Glenn’s drawings are extremely detailed. He takes about 20 to 25 hours on average with each one. He doesn’t draw from memory or on the spot, but always works from a photograph. Glenn doesn’t draw from left to right, but he’ll jump around the picture. Sometimes I’ll watch him working, and I’ll see something random, and I’ll ask him – is that a mistake? But he’ll say: “Daddy, that’s my starting point.” When he’s done with the picture, you’ll have no idea where he started.

Member of Parliament Denise Phua, who helped set up Pathlight, called Glenn “the Stephen Wiltshire of Singapore”, referring to the famous British artist who has autism.

When Glenn was younger, we would worry about his future. Now, we’re definitely more confident. Pathlight recently set up an art gallery for its artists, which also sells works by students who have graduated. It feels like there’s a direction for Glenn now, and he can earn a living.

Glenn Phua, see here with his father Kelvin, was found to be autistic when he was four. His artistic talent was discovered when he won an art competition.

Glenn Phua, see here with his father Kelvin, was found to be autistic when he was four. His artistic talent was discovered when he won an art competition.

Living The Singapore Story: Celebrating Our 50 Years 1965–2015 is on sale in bookshops at $19.65 (GST included). Commissioned by the National Library Board in celebration of Singapore’s Jubilee year, it features 58 Singaporeans describing how their lives evolved as Singapore changed over the past half-century. The stories featured on these pages are excerpts from the book.

The team members behind the book, led by The Straits Times Editor-at-large Han Fook Kwang, are journalists Angelina Choy, Cheong Suk-Wai and Jennani Durai, former journalist Cassandra Chew and photographer Bryan van der Beek. A 15-member editorial advisory committee was chaired by Ambassador-at-large Tommy Koh and the NLB team was led by Francis Dorai, Assistant Director (Publishing).

This article and selected excerpts were first published in The Sunday Times on 17 May 2015. © Singapore Press Holdings Limited. Reprinted with permission.

Han Fook Kwang joined The Straits Times in 1989 and became its political editor in 1995. He served as editor of the paper from 2002 to 2012. He is currently Editor-at-large at the newspaper.