When Singapore Was Cinca Pula

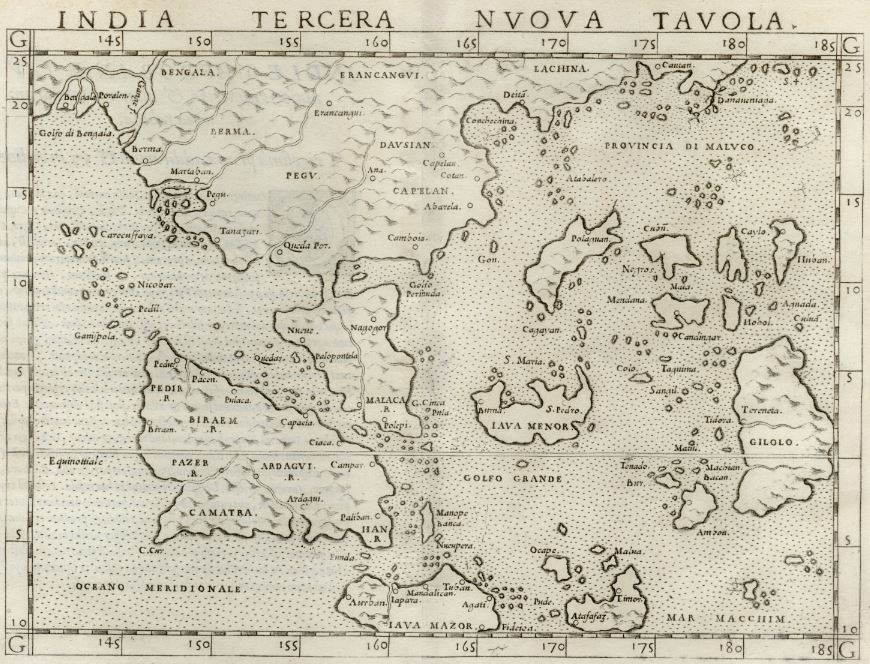

Title: India Tercera Nuova Tavola

Creator: Girolamo Ruscelli (c. 1504–1566)

Year published: 1561

Publisher: Vincenzo Valgrisi (Venice)

Language: Italian

Type: Map; 17cm by 23cm

Call no.: RRARE 912.59 PTO

Accession no.: B20023657C

A 455-year-old map of Southeast Asia tells of the seafaring adventures of 16th century voyagers, whose journeys took them to exciting, uncharted territories waiting to be explored. As the intrepid voyagers discovered new trade routes in Asia, these unknown lands slowly came into prominence. We are familiar with most of them today; one, in particular, stands out – a place indicated on the map as C. Cinca Pula.

India Tercera Nuova Tavola is one of the first early modern maps of Southeast Asia. It is also the National Library’s earliest map that makes reference to a Cinca Pula – which scholars believe refers to either the town of Singapore, one of several straits on which Singapore sits, a cape, or the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula.1 In this map, Cinca Pula refers specifically to a promontory – C.[abo] Cinca Pula or Cape of Cinca Pula. Re-issued up until 1599, the map was created at a time when European traders were exploring new routes to the East of India, including the Spice Islands in Southeast Asia.2 Singapore’s presence on this map suggests that it had an active role in the pre-colonial trade in the region.

Created by the Italian cartographer Girolamo Ruscelli, the map, which is slightly smaller than a sheet of A4 paper, is made up of two sheets of paper seamed together. Ruscelli’s map is based on a pocket-sized engraving created in 1548 by another Italian cartographer, Giacomo Gastaldi. Gastaldi, in turn, had based the map on the groundbreaking work of the 2nd-century Greek mathematician and astronomer Claudius Ptolemy as well as information gleaned from new European discoveries. Ptolemy’s use of the grid system in his work Geographia (or in English, Geography) to map the world became the basis of modern cartography as we know it today.

Gastaldi’s map marked a significant shift away from the traditional practice of woodblock printing, the method used to produce Ptolemic maps.3 Engraved on copper, Gastaldi’s maps were clearer and more detailed than woodblock printed maps; this costly method of printing maps had been abandoned for four decades before it was revived by Gastaldi.4

Gastaldi’s map also showed a distinct departure from Ptolemy’s cartographical representation of the Far East. Ptolemy used a systematic grid of longitudes and latitudes linked to specific points, while Gastaldi’s maps were based on Portuguese portolans – navigational charts constructed from compass points and sailing directions – and showed coastal outlines with few inland features.5

ln 1561, Ruscelli enlarged Gastaldi’s map to twice its size and published it in his book, La Geographia di Claudio Tolomeo Alessandrino. Two other editions of the map were subsequently produced in 1574 and 1599.6

Spanning the Bay of Bengal to southern China in the north, and down just below the Equator to the south, India Tercera Nuova Tavola depicts new information about the region gathered from Spanish and Portuguese explorers. For example, the southward extension of the Malay Peninsula, shaped like an upside-down leaf, is corrected for geographical accuracy, while Ptolemy’s Sinus Perimulicus, regarded now as the Gulf of Siam, is retained as Golfo Permuda on this map.7

Malaca (Melaka), having been conquered by the Portuguese in 1511, is clearly marked, as are kingdoms with trading or diplomatic ties with the Portuguese. These include Camatra (Sumatra), Iapara (Jakarta), Pazer (Pasai), Pacem (Aceh), Campar (Kampar) and Ardagui (Indragiri). Other areas in Southeast Asia, such as Banca (Bangka), St. Pedro (Mount Kinabalu), Berma (Burma) and Camboja (Cambodia), are also identified for the first time.8

The map, which the National Library Board acquired in 2012, offers historians valuable insight into the trade, politics and geography of 16th-century Southeast Asia.

– Written by Irene Lim

NOTES

-

Borschberg, P. (Ed.). (2004). Remapping the Straits of Singapore: New insights from old sources? In Iberians in the Singapore-Melaka Area and adjacent regions (16th to 18th century) (p. 96). Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz; Lisboa: Fundação Oriente. Call no.: RSING 959.50046 IBE; Borschberg, P. (2005). Fictitious strait and imagined island: “Singapura” in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century, water and state in mainland Southeast Asia. Retrieved from academia.edu website; Borschberg, P. (2010). The Singapore and Melaka straits: Violence, security and diplomacy in the 17th century (p. 21). Singapore: NUS Press. Call no.: RSING 911.16472 BOR. ↩

-

Parry, D. E. (2005). The cartography of the East Indian Islands = Insulae Indiae Orientalis (p. 69). London: Country Editions. Call no.: RSING q912.59 PAR; Suarez, T. (1999). Early mapping of Southeast Asia (p. 130). Hong Kong: Periplus. Call no.: RSING q912.59SUA. ↩

-

Campbell, T. (1987). The earliest printed map 1472– 1500 (p. 11). London: The British Library. Call no.: R 912.09024 CAM; Suarez, 1999, p. 130. ↩

-

Campbell, 1987, pp. 4–5; Parry, 2005, pp. 43, 70; Harvey, P. D. A. (1991). Medieval maps(pp. 39–45), London: British Library. Call no.: R 912.0902HAR. ↩

-

Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. (1842). Biographical dictionary of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. (Vol. 1, Part 2, p. 827). London: Longman, Green, Brown and Longmans. Retrieved from Google Books. ↩

-

Durand, F. (2013). Maps of Malaya and Borneo: Discovery, statehood and progress: The collections of H.R.H. Sultan Sharafuddin Idris Shah and Dato’ Richard Curtis (p. 82). Singapore: Editions Didier Millet Pte Ltd. Call no.: RSEA 912.5951 DUR; Suarez, 1999, pp. 147–149. ↩