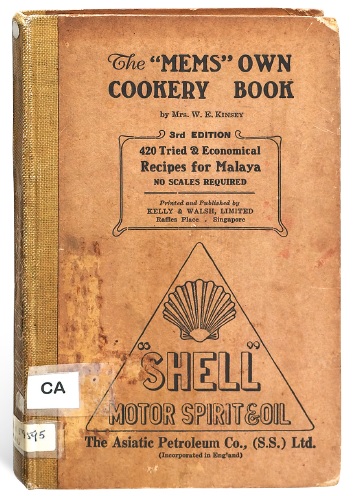

A Colonial Cookbook

Title: The “Mem’s” Own Cookery Book: 420 Tried and Economical Recipes for Malaya

Author: Mrs W. E. Kinsey

Year published: 1929 (3rd edition)

Publisher: Kelly & Walsh, Limited (Singapore)

Language: English

Type: Book; 171 pages

Call no.: RRARE 641.59595 KIN

Accession no.: B02938274B

The first edition of The “Mem’s” Own Cookery Book, issued in 1920, sold out within a few months; the second edition, published in 1922, was so popular that a third was published in 1929. This is the cover of the third edition. All rights reserved, National Library Board, Singapore.

The first edition of The “Mem’s” Own Cookery Book, issued in 1920, sold out within a few months; the second edition, published in 1922, was so popular that a third was published in 1929. This is the cover of the third edition. All rights reserved, National Library Board, Singapore.The year 1914 brought with it the devastation of World War I, and the beginning of widespread food shortages and hikes in food prices. The expatriate community in Malaya was not spared either, but one woman’s passion for cooking – documented in a compilation of 420 recipes – helped numerous expatriate women in the region prepare flavourful meals for their families on their shoestring budgets.

First published in 1920, the book, titled The “Mem’s” Own Cookery Book: 420 Tried and Economical Recipes for Malaya, was written by Mrs W. E. Kinsey, the wife of British expatriate William Edward Kinsey. Her recipes were based on local ingredients, and came with notes on prices and where the ingredients could be bought more cheaply.1 This made the book a lifesaver for hapless foreign mems – the term used by employees of colonial families for the lady of the house – who faced myriad cultural challenges running households in Malaya.2

“Mem” is likely a corruption of “Madam” and often used in conjunction with “Sahib” the Indian term of address for the man of the house; “mem” is a shortened form of “memsahib”, which was commonly used to address the wives of British colonial officers in India.3

Every recipe in the book was personally tested by Mrs Kinsey in her home kitchen in Seremban, Malaya, between 1915 and 1919. At the time, ingredients that appealed to expatriate tastes were scarce, especially for those who lived on plantations without ready access to food supplies. As family finances became tighter, some expatriates began using local ingredients as a cheaper alternative to imported food.4

Some of the popular local ingredients featured in Mrs Kinsey’s recipes were lady’s fingers, marrow, corn and lentils, as well as local fish such as ikan kurau (threadfin) and ikan merah (red snapper). Local spices such as curry powder, cloves, ginger, garlic and bay leaves were also frequently used.

Recipes aside, Mrs Kinsey provided detailed information on shopping for ingredients. For example, in her mutton broth recipe, she listed varying prices of mutton at the local market and at Cold Storage – the supermarket most frequented by expatriates at the time. If money was no issue, imported foods such as pheasants, haddocks and kippers, tinned fish, canned vegetables and processed foods could be bought at Cold Storage.

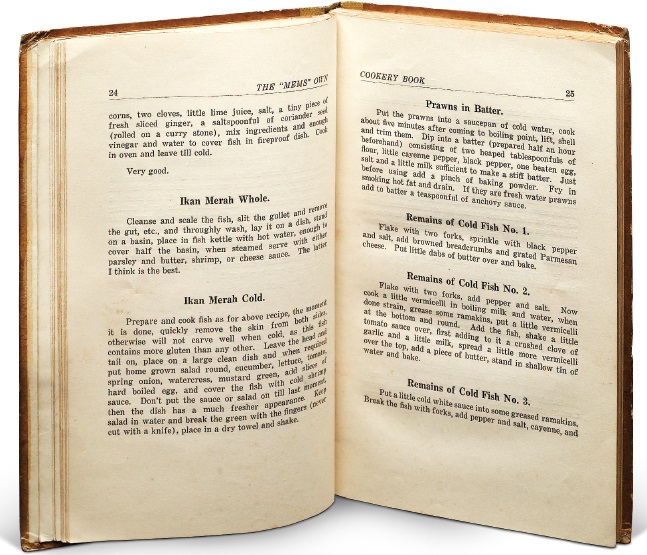

The book’s focus on economy was apparent too: many of the recipes used various kinds of leftovers. Leftover meats were often used to make soup, and the remains of cold fish could be baked with cheese, vermicelli and milk, or steamed with a beaten egg.

Other interesting dishes using leftovers included minced remnants of a steamed chicken cooked with the seaweed-derived jelly called agar agar and milk to make creamed chicken aspic, as well as leftover cold vegetables such as cabbage mashed with potatoes, shaped into cakes and pan fried to make a breakfast dish called “bubble and squeak”.

Mrs Kinsey’s cooking methods were typically British – most of her dishes involved boiling, baking and roasting. Because ingredients were limited, a variety of cooking methods were used to prepare different dishes using the same few ingredients. For example, the book showcased six different ways to prepare ikan kurau – including baking, boiling, frying or smoking.

Mrs Kinsey’s cooking methods were typically British – most of her dishes involved boiling, baking and roasting. Because ingredients were limited in Malaya, a variety of cooking methods were used to prepare different dishes using the same few ingredients. Image source: National Library Board, Singapore.

Mrs Kinsey’s cooking methods were typically British – most of her dishes involved boiling, baking and roasting. Because ingredients were limited in Malaya, a variety of cooking methods were used to prepare different dishes using the same few ingredients. Image source: National Library Board, Singapore.Though her book was very well-received – the first issue sold out within a few months, and the second edition, published in 1922,5 was so popular that a third was published in 19296 – little is known about the woman behind the recipes, not even her first name. What is known, however, is that Mrs Kinsey, unlike many other expatriates who hired cooks, did her own cooking on an oil-fired stove on the back verandah behind her dining room.7 She was also well-known for her homemade fruit preserves, some of which were featured at the 1924 and 1925 Wembley Exhibition in England showcasing pickles, chutneys and jams made with Malayan fruits.8

More is known about her husband, William Edward Kinsey, who arrived in Malaya from Liverpool in 1898 to help his father run the Pahang Exploration and Development Company. In 1902, Kinsey entered the government service as Inspector of Mines in Negri Sembilan, and retired in 1924 from his post as Deputy Conservator of Forests of Negri Sembilan and Malacca.9

After the first cookbook was published, Mrs Kinsey went on to publish a sequel, The Next Meal, in 1931. The two books were packaged into a neat box, meant to fit in the kitchen as a handy resource for the foreign mems.10

– Written by Irene Lim

NOTES

-

Tan, B. (2011). Malayan cookery book: The mem’s own cookery book. BiblioAsia, 7 (3), 30–34. ↩

-

Page 6 Advertisements Column 3. (1934, January 30). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Europeans in the East. (1919, October 22). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Untitled. (1922, May 5). The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The literary page – new books reviewed. (1930, January 31). The Straits Times, p. 17. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Wanderer. (1933, September 10). Mainly about Malayans. The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Untitled. (1925, October 9). The Singapore Free Press, p. 16; Untitled. (1925, April 7). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 31 Jan 1930, p. 17. ↩