A Singapore-made Qur’an

To mark Hari Raya Puasa, we are resurfacing this article that was first published in 2016.

Title: Lithographed Qur’an

Copyist: Tengku Yusof bin Tengku Ibrahim

Year published: 1869

Publisher: Haji Muhammad Nuh bin Haji

Ismail (printed in Singapore)

Language: Arabic

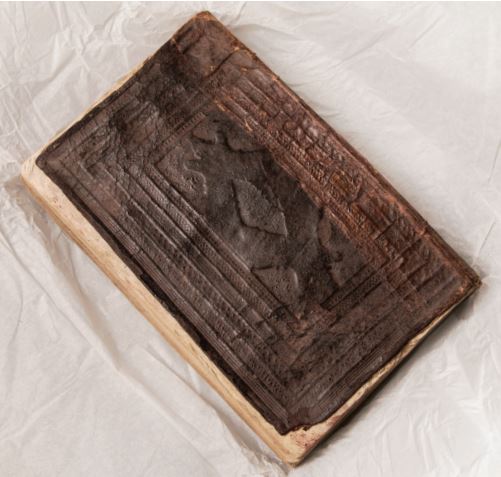

Type: Book; 620 pages

Accession no.: B26075403E

Donated by: Dr Farish Noor

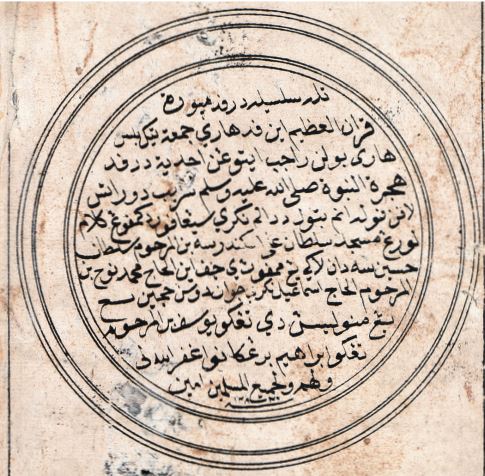

This edition of the Qur’an in the National Library is unique because it is one of the earliest extant copies to have been printed at Kampong Gelam in Singapore. The date of its publication, “13th Rajab in the (Islamic) year 1286” corresponds to 19 October 1869. This information in Jawi (Malay written in modified Arabic script), along with the address of the printer –Lorong Masjid Sultan Ali Iskandar – in the Kampong Gelam area, is indicated in the colophon or publisher’s imprint, at the end of the book. In addition, the colophon also contains the name of the printer (Haji Muhammad Nuh bin Haji Ismail) and the copyist (Tengku Yusof bin Tengku Ibrahim).

Pre-20th-century Southeast Asian Qur’ans, whether handwritten or printed, are generally scarce because the region’s tropical climate is not conducive to the preservation of paper-based materials. Colophons especially, if they are even included in the book, do not often survive as they undergo much wear and tear due to their placement at the front or end pages. This rare copy of the Qur’an is a product of the pioneering phase (1860–80) of Muslim1 publishing in Singapore.

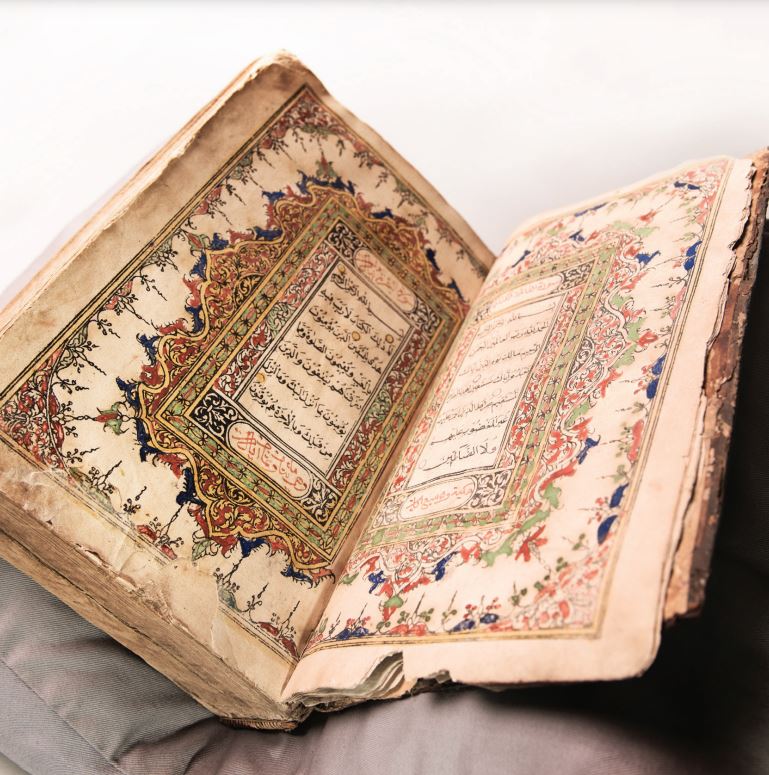

The book begins with instructions on tajwid (rules on the recitation of the Qur’an) before the Qur’anic text begins. It contains three decorated double-spread pages in the beginning, middle and end. The designs found on the double-spreads at the beginning and the end are exactly the same, although they been coloured differently. On closer inspection, the blue, green, yellow (likely imitating gold) and red inks have been applied rather clumsily. In terms of design, this Qu’ran is reminiscent of the highly prized and ornate manuscript Qur’ans produced in Terengganu,2 in the east coast of the Malay Peninsula.

In typical Terengganu-style Qur’ans, the text box on the double-spread pages is usually enclosed within a series of decorated rectangular borders and lobed arches that form a continuous outline on the three outer edges of the box. The opening and closing double-spreads also feature decorative borders on the outer edges of the pages with finials that project towards the lobed arches. Annabel Gallop, a scholar of Malay manuscripts, calls this decorative feature a “stalagmite-stalactite” effect.3

The copyist of this Qur’an, Tengku Yusof bin Tengku Ibrahim of Terengganu, enjoyed the distinction of being one of two principal copyists working in Singapore during the late 19th century.4 As elaborate manuscript Qur’ans from the east coast of Malaya (Terengganu, Kelantan and Patani) were widely sought after in the Malay archipelago back then, it is not altogether surprising that a lithographed Qur’an produced in Singapore would have been designed to look like one from that region –it would have made good business sense to sell Qur’ans that were in demand.

The Malay manuscript tradition played a big influence during the early phase of Muslim printing in Singapore. The lithograph basically reproduced the format of the original manuscript but allowed multiple copies of the book to be printed economically. The copyist would transcribe the text in special ink which would then be transferred onto the lithographic stone.5 As an acknowledgement to the manuscript tradition, early lithographed books often gave prominent mention of the copyist, as seen in the colophon of this Qur’an.

During the late 19th century, Singapore or more specifically Kampong Gelam, was the leading centre for Muslim publishing in the region, with its products widely distributed throughout the Malay world. According to scholar Ian Proudfoot, it was mainly entrepreneurs of Javanese ancestry who tended to dominate the early Muslim book printing scene.6

The printer of this Qur’an, Haji Muhammad Nuh bin Haji Ismail, from Juwana, a town on the north coast of Java, was one of the major players at the time. His shop was located on Lorong Masjid Sultan – a street that used to extend from the main gate of the Sultan Mosque. Many other printing shops were also clustered around the mosque because it was a place where the Muslim community naturally congregated for Friday prayers. Pilgrims heading to Mecca would similarly gather here. In the 19th century, Singapore was an important stop for pilgrims from the Netherlands East Indies (present-day Indonesia) before their journey to and from Mecca. This was partly due to the restrictive regulations on travel that the Dutch imposed on people making the haj (pilgrimage).7

This particular Qur’an, donated by the academic and writer Dr Farish Noor in 2015, was purchased in Java. It could have been brought to Java by a returning pilgrim from Singapore or distributed there by the printer.

– Written by Tan Huism

NOTES

-

The term “Muslim” is used here in the same way as Ian Proudfoot, to refer to the religious faith of the agents who produced the materials and not necessarily the content of the publications. The earliest known printed Qur’an produced in Southeast Asia was published in 1854 by a Muslim from Palembang who bought the lithographic press from Singapore. Based on confirmed dated materials, Islamic printing existed in Singapore from 1860 onwards. See Proudfoot, I. (1993), Early Malay printed books: A provisional account of materials published in the Singapore-Malaysia area up to 1920, noting holdings in major public collections (pp. 27, 432). Malaysia: Academy of Malay Studies and the Library, University of Malaya. Call no: RSING 015.5957 PRO-[LIB] ↩

-

See for example, Tan, H. (2010, January/February). A royal Terengganu Qur’an in the Collection of the Asian Civilisations Museum. Arts of Asia. Call no: R709.5AA ↩

-

Gallop, A. T. (2005, July). The spirit of Langkasuka? Illuminated manuscripts from the East Coast of the Malay Peninsula. Indonesia and the Malay World, 33 (96), 118. Retrieved from Academia website. ↩

-

Proudfoot, I. (1986). A formative period in Malay book publishing. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 59 (2) (251), 110. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

The Dutch government in the Netherlands East Indies was suspicious and fearful of the “subversive” influence of returning haji (pilgrims), so set about instituting restrictions to hinder travel to Arabia. See Roff, W. (1964). The Malayo-Muslim world of Singapore at the close of the nineteenth century. The Journal of Asian Studies, 24 (1), 75–90. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩