Beach Road Camp and the Singapore Volunteer Corps

The SVC was the precursor of the first organised military service in Singapore and marked the beginning of a volunteer movement that would last for over a century. Francis Dorai has the story.

Soldiers from the Singapore Voluntary Royal Artillery unit outside the Drill Hall at Beach Road Camp, 1928. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Soldiers from the Singapore Voluntary Royal Artillery unit outside the Drill Hall at Beach Road Camp, 1928. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Just opposite Raffles Hotel along Beach Road is the former Beach Road Camp, restored to its original glory amidst the soaring twin towers of the South Beach development. The entire strip of land opposite Raffles Hotel to its northern tip where Beach Road meets Crawfurd Street was reclaimed from the sea, in stages beginning from the 1840s onwards – hence its name Beach Road.

The history of Beach Road Camp is closely linked to the defence and political history of Singapore. This was where the Singapore Volunteer Corps (SVC) – the first semblance of a homegrown military force – had its headquarters at the turn of the 20th century. The SVC has a long history that mirrors Singapore’s evolution, and it isnot possible to appreciate the heritage value of Beach Road Camp without understanding Singapore’s military history.

The Fortification of Singapore

In One Hundred Years of Singapore, Walter Makepeace rues the fact that “the history of Singapore as a fortified place does not reveal any creditable or consistent policy”. Stamford Raffles had approved, in a memo dated 6 February 1819, the construction of a “small fort… capable of mounting eightor ten-pounders”, “a barracks for thirty European” soldiers, and “one or two strong batteries for the protection of shipping” on the coast, along with a watchtower. These scant provisions in Raffles’ view “render the Settlement capable of maintaining a good defence”.1

In reality, Raffles was probably too caught up with other pressing issues to pay serious attention to the fortification of Singapore. Although a skeletal police force of 17 constables had been set up as early as 1821 and its numbers beefed up in subsequent years, it soon became clear that the increasing lawlessness in the colony was too much for the police to handle. Murders and petty theft occurred on a regular basis, and Chinese secret societies and gang clashes were a constant menace. By the 1850s, there were at least 6,000 Chinese triad members looting, plundering and murdering with impunity.

The SVC: Its Beginnings

The last straw was the violence unleashed by the horrific Chinese secret society clashes of 1854 involving the Hokkien and Teochew factions that claimed the lives of as many as 500 people and razed over 300 houses in the course of a week. What had appeared to be a minor fracas between a Hokkien and Teochew in the town market grew in intensity, and the atrocities spread to the outlying areas like wildfire, with the “heads of the dead being cut off and carried on the spears of their adversaries”.2 Thousands of dollars were lost as commercial trade in the settlement drew to a halt. As the skeletal police force was ineffective in quelling the disorder, residents and officers of ships in the harbour were roped in to help bring calm to the island.

It was clear that such security flareups were beyond the scope of a regular police force, so on 8 July 1854 permission was granted by the Governor of the Straits Settlements, William J. Butterworth, to form the Singapore Volunteer Rifle Corps (SVRC). There was a total of 61 members, all voluntary, mostly drawn from the European and local Eurasian communities (the latter bearing surnames like Tessensohn, Reutens and Paglar) and led by British officers. Notable Beach Road British residents like William H. Read and John Purvis were among the first volunteers and were promoted to leadership positions swiftly.

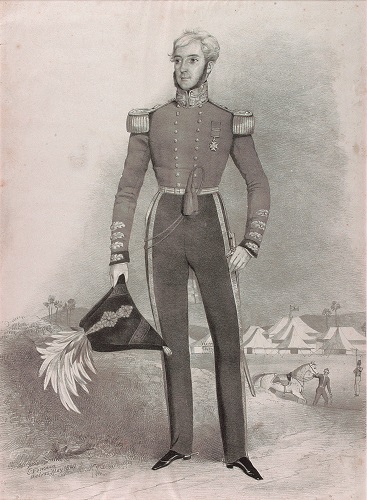

William J. Butterworth, Governor of the Straits Settlements (1843–55), was the Colonel-in-charge of the Singapore Volunteer Rifle Corps in when it was formed 1854. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

William J. Butterworth, Governor of the Straits Settlements (1843–55), was the Colonel-in-charge of the Singapore Volunteer Rifle Corps in when it was formed 1854. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.Butterworth assumed leadership as the Colonel-in-charge and Captain Ronald MacPherson of the Madras Artillery was appointed as the Commandant. The SVRC was meant to bolster the resident police force in dealing with large-scale violence and disorder, not replace it. The SVRC was the precursor of the first organised military service in Singapore and marked the beginning of a volunteer movement that would last for over 100 years.

In 1857 and 1871, the SVRC was again placed on high alert as full-scale riots by the Chinese community erupted. All this time, SVRC members had kept themselves in top form by engaging in weapon training, drill practices and field camps. In addition, the SVRC assumed fire-fighting and ceremonial duties such as taking part in parades to mark important occasions and escorting dignitaries during their visits to Singapore.

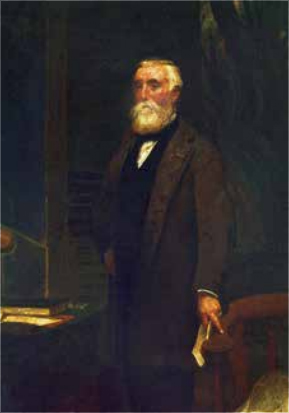

Wealthy British merchant and Beach Road resident William H. Read was one of the first volunteers of the Singapore Volunteer Rifle Corps. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

Wealthy British merchant and Beach Road resident William H. Read was one of the first volunteers of the Singapore Volunteer Rifle Corps. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.The SVC: 1887 to 1949

By 1887, however, the SVRC had dwindled to about half its original size, and in 1888, it was disbanded and re-organised as the Singapore Voluntary Artillery (SVA). All this while, the voluntary corps was largely European in composition. However, by 1894, there were enough Eurasians, bolstered by volunteers like J. B. Westerhout, Edgar Galistan and R. D. de Silva, to form the Singapore Voluntary Infantry No. 1 Company (Eurasian). The Straits Chinese, or Peranakans, felt there was a need to stake a claim too in the SVC, and in answer to their petitions, the Singapore Voluntary Infantry No. 2 Company (Chinese) was founded in 1901.

In 1901, these three sub-units, along with the Singapore Voluntary Rifles and Singapore Voluntary Engineers, were amalgamated under the Singapore Volunteer Corps (SVC) banner. One of the SVC’s biggest roles in the following decade was the suppression of a revolt in 1915 – later known as the Singapore Mutiny, or the Sepoy Mutiny (see text box below) – by some 800 soldiers of the Indian Army against their British masters in Singapore.

In October 1914, the British sent the Indian Army’s 5th Light Infantry Regiment to Singapore to bolster the island’s defences. But within four months, the company of 800 Indian soldiers, comprising mainly Muslims of Rajput origins, broke out into a bloody revolt. When the dust settled a week later, a total of 47 British officers, British residents and local civilians had been slain. The causes of the mutiny were complex, ranging from unhappiness with the British commanding officers to fears among the Muslim soldiers of being shipped out and forced to fight their brethren in Turkey. Two roads were later named in memory of the British soldiers who died in the mutiny: Harper Road and Holt Road, after Corporal J. Harper and Private A. J. G. Holt respectively.

By 1921, the SVC had two battalions with four companies each, including two British, and one each of Eurasian, Chinese and Malay volunteers, and specialist companies like artillery, engineers and field ambulance. Barely a year later, the SVC would undergo another change in structure; as part of Singapore’s obligations to the Straits Settlements (comprising Singapore, Penang and Malacca), the SVC was re-organised as the Straits Settlements Volunteer Force (SSVF), joining volunteer corps from Penang and Malacca. The SVC, however, retained its identity under the SSVF umbrella, maintaining its two battalions until World War II. In the inter-war period, the volunteer forces were kept busy with recruitment and training, and were occasionally mobilised when the police force needed reinforcement.

But generally, the SVC kept a relatively low profile until World War II – when Singapore was dragged into the fray. The combined British and Allied forces, along with the SVC, were no match for the Japanese, and the “impregnable fortress” that Singapore was made out to be crumbled on 15 February 1942. The British had made a tactical error in assuming that the Japanese would invade by sea and were unprepared for the enemy’s advance by land from the north. As many as 80,000 soldiers and SVC members were rounded up by the Japanese as prisoners-of-war; some were sent to Burma to work on the infamous Death Railway while others were summarily executed (about 2,000 SVC personnel were reportedly killed for their collaboration with the British).

Paul Cheah Thye Hong was only 11 years old when Singapore fell to the Japanese but the event has been permanently seared into his memory. “A few days after, the Japanese went on a witch-hunt, rounding up all male Chinese above the age of 15 for interrogation. The Chinese were targeted for their perceived loyalty to China,” he recalls. All of Cheah’s four older brothers were called up, including his 22-year-old brother Thye Hean, an SSVF soldier. “Thye Hean had just returned home on the eve of the British surrender, after being instructed by his officer to discard his uniform and blend in with the civilian population,” Cheah remembers.3 Unluckily, at the screening centre, Thye Hean was identified as an SSVF member by a traitor. He was bundled into a lorry with other young Chinese men, taken to a remote spot and presumably executed by the Japanese. Thye Hean’s body was never found, but his name is enshrined at the Kranji War Memorial honouring the dead.

Medals of honour awarded posthumously to Straits Settlements Volunteer Force volunteer Private Cheah Thye Hean, who was executed by the Japanese in 1942. Thye Hean’s body was never found, but his name is enshrined at the Kranji War Memorial honouring the dead. Courtesy of Paul Cheah Thye Hong.

Medals of honour awarded posthumously to Straits Settlements Volunteer Force volunteer Private Cheah Thye Hean, who was executed by the Japanese in 1942. Thye Hean’s body was never found, but his name is enshrined at the Kranji War Memorial honouring the dead. Courtesy of Paul Cheah Thye Hong.After the Japanese troops surrendered to the Allied forces in September 1945, the British returned to Singapore. But World War II had radically altered the face of global politics, and while the British were warmly welcomed as reprieve from Japanese atrocities, the conditions on the ground had changed: nationalism had been fuelled and the locals were gunning for independence. On 1 April 1946, the Straits Settlements was dissolved and the SSVF subsequently disbanded.

Post-war Singapore was a dismal scene: inflation was high, many people were jobless and angry, and there was a persistent shortage of basic essentials. Against a backdrop of political activism, the Malayan Communist Party began a struggle for power, working through the labour unions in Singapore to instigate labour unrest and strikes. In Malaya, the armed Communist struggle became serious enough for the British to declare “a state of emergency” in June 1948. With its men and resources tied up in dealing with the situation in Malaya, the British decided to revive the SVC in 1949 as a means of dealing with domestic issues of law and order.

The SVC was reorganised and its composition became more multi-racial in character – the European, Eurasian, Malay and Chinese companies were all dropped. And for the first time, locals were given key appointments within the SVC, attracting new volunteers to join the corps. This was history in the making, as over time, the SVC would evolve into the modern Singapore Armed Forces.

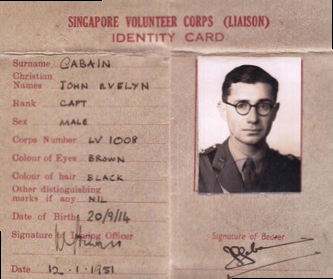

Identity card of Captain John Evelyn Gabain, a Eurasian volunteer with the SVC in 1951. J. E. Gabain Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Identity card of Captain John Evelyn Gabain, a Eurasian volunteer with the SVC in 1951. J. E. Gabain Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.The SVC: Post-War Period

In the meantime, nationalistic agitations in Singapore were being whipped into a frenzy. Bowing to pressure, the British allowed for the election of six members to a new 22-member Legislative Council on 1 April 1948. This heralded the start of an 11-year struggle for self-government, resulting in the exit of the British from the Singapore political scene in June 1959.

The decade between 1948 and 1959 was a tumultuous time for the island in terms of internal security, filled with communist instigated and racial riots as well as student and labour unrests. Both the police force and the SVC had their hands full dealing with one crisis after another. This, coupled with the shifting geopolitical landscape and concerns about external threats, led the British to pass two laws on 15 December 1953 – the National Service Ordinance, 1953, and Singapore Military Forces Ordinance, 1953. The first legislation allowed for mandatory conscription and, the second, for the formation of a military force to oversee the local volunteers and national servicemen.

Despite an outbreak of riots on 13 May 1954 by Chinese middle school students who vehemently opposed the conscription, the plans for national service went ahead. The colonial government went on a publicity blitz and notifications were sent out to all male citizens between the ages of 18 and 20. Some 24,000 young men signed up, but as the authorities could not cope with such large numbers, a public ballot was held in June 1954. A week later, the first batch of 400 recruits reported for training at Beach Road Camp. The conscripts were put through their paces by the SVC, aided by a number of British army regulars. The date 15 December 1954 marked a proud moment for these 400 soldiers as they celebrated their transition from recruits to privates at the passing-out parade held at Beach Road Camp.

At the same time, Beach Road Camp became the new headquarters of the Singapore Military Forces (SMF), which was put in charge of the training and administration of both the SVC and national servicemen for the next few years.

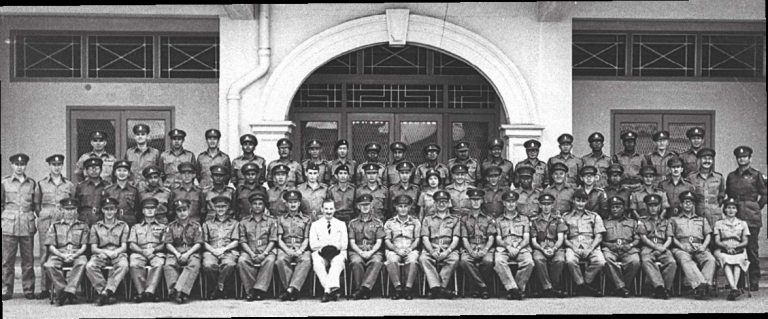

Group photo of the Singapore Volunteer Corps taken at Beach Road Camp, circa 1959. David Ng Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Group photo of the Singapore Volunteer Corps taken at Beach Road Camp, circa 1959. David Ng Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Beach Road Camp: Headquarters of the SVC

Throughout its complex history and various name changes, the SVC maintained a physical presence. Its first centre – a rather modest Drill Hall of wood and corrugated iron – was built in 1891, along the shores of Fort Fullerton (today the site of Fullerton Hotel). In 1907, that structure was dismantled and moved to a strip of coastal land on Beach Road, where the Chinese Volunteer Club – headquarters of the SVC’s Chinese Company – had been standing since 1904. The transplanted Drill Hall was used as the new headquarters of the SVC. This makeshift structure existed for over two decades, a reflection perhaps of the transient nature of the SVC at the time.

But all this was to change in 1930. The SVC became more entrenched, and proper space was required for both training and recreation. Construction work on the new Drill Hall – based on a design by the colonial architect Frank Dorrington Ward – began in 1931. Its location on what was prime beach-facing land at the time must have surely incensed the owners of Raffles Hotel just opposite as some of the sea views it enjoyed slowly became obscured.

The foundation stone for the new Drill Hall (Block 9) was laid on 8 March 1932 by Governor of the Straits Settlements Cecil Clementi. A year later, on 4 March 1933, the old Drill Hall was demolished and the new building, the headquarters of the SVC – or SSVF as it was known then – was declared open by Clementi and the symbolic Golden Key presented.

In 1933, the old Drill Hall was replaced by a permanent concrete structure designed by the colonial architect Frank Dorrington Ward. This building, Block 9, still stands today. Courtesy of Prof Cheah Jin Seng.

In 1933, the old Drill Hall was replaced by a permanent concrete structure designed by the colonial architect Frank Dorrington Ward. This building, Block 9, still stands today. Courtesy of Prof Cheah Jin Seng.The architecture and facilities were something to behold at the time, with its stepped-up exterior, generous verandahs, Art Deco detailing and a 140-ft (43-m) long column-free drill hall with a soaring 40-ft (12-m) high vaulted ceiling. The building opened up to lovely sea views on one side, although this would gradually disappear over time as more land was reclaimed from the sea. On the Beach Road side was a striking double-height narrow vertical window embellished with the SVC regimental insignia.

In subsequent years, more buildings were added to the site. The Chinese Volunteer Club (Block 1), which predates the 1907 wood-and-corrugated-iron Drill Hall, was likely expanded in later years according to historic records. Block 14 was constructed in 1939 for the Malay Company of the SVC, and the NCO Club, formerly the Britannia Club, was a 1952 addition.

The Birth of 1 SIR

In the 1950s, the SVC was beefed up with more support units, including the Singapore Royal Artillery, Singapore Armoured Corps and the Women’s Auxiliary Corps (WAC). The latter attracted both local as well as British women, and one of its most well-known local volunteers was the war heroine Elizabeth Choy.

By the early 1950s, Singapore nationalists like David Marshall, who were pressing the British for self-government, started making a case for a full-fledged regular army made up of local citizens. Marshall, who became Singapore’s first Chief Minister in 1955, was himself an SVC member during World War II and was interned at Changi Prison before being sent to a labour camp in Japan. The SVC was all fine and good, the critics said, but ultimately it was an outfit set up by the British and therefore not completely independent and impartial. While the rank and file of the SVC were mainly locals, most of the officers were British, and many locals felt they were discriminated against when it came to salaries and promotions.

It was only in 1957 that the go-ahead was given to start the first independent Singapore army, laying down the foundations for the 1st Battalion, Singapore Infantry Regiment (or 1 SIR for short) – a professional fighting force of Singapore born regular soldiers. On 15 February 1957, press announcements called for Singaporean men between the ages of 18 and 25 to apply, as long as they were “the adventurous type, fond of outdoor and rugged life, and… prepared to make the army a career”.4 Some 1,420 men applied but only 237 were accepted.

Although 1 SIR was to have its base at Ulu Pandan Camp in the west of Singapore, Beach Road Camp, the headquarters of the Singapore Military Forces, was chosen as the site of the recruitment interviews and attestation parades. On 12 March 1957, the first 22 recruits (11 Chinese, 7 Malays, 3 Eurasians and 1 Sikh) were sworn into 1 SIR by Magistrate T. S. Sinnathuray – himself a member of the SVC. Over the following months, more young men joined the army, and by October 1958, a total of 842 recruits had been sworn in at Beach Road Camp.

The original Drill Hall was a makeshift wood-and-corrugated iron structure erected at Fort Fullerton near the entrance of the Singapore River in 1891. This would be the temporary home of the Singapore Volunteer Corps for the next 15 years. Courtesy of Prof Cheah Jin Seng.

The original Drill Hall was a makeshift wood-and-corrugated iron structure erected at Fort Fullerton near the entrance of the Singapore River in 1891. This would be the temporary home of the Singapore Volunteer Corps for the next 15 years. Courtesy of Prof Cheah Jin Seng. In 1907, the wood-and-corrugated-iron Drill Hall at Fort Fullerton was physically moved to its new location along Beach Road and re-assembled. Courtesy of Prof Cheah Jin Seng.

In 1907, the wood-and-corrugated-iron Drill Hall at Fort Fullerton was physically moved to its new location along Beach Road and re-assembled. Courtesy of Prof Cheah Jin Seng.End of SVC and Start of PDF

With 1 SIR and 2 SIR (the latter inaugurated in 1962) in full swing, the SVC provided an additional layer of security between 1958 and 1965. During the prickly Confrontation years with Indonesia (1963–65), soldiers from 1 SIR and 2 SIR were deployed in Borneo and Johor and, together with the SVC, protected vital installations in Singapore.

With the worst of the Confrontation over by mid-1965, Singapore found a new problem on its hands. Having parted company with the Federation of Malaysia on 9 August 1965, it had to deal with a raft of new issues, not least of which was security.

The government therefore passed the People’s Defence Force Act on 30 December that same year and the SVC was renamed the People’s Defence Force (PDF). A number of SVC units were absorbed into the Singapore Armed Forces (SAF) – which had been renamed from the Singapore Military Forces in 1965 – and many of the volunteer officers made the switch to the regular army. Only one battalion of volunteers remained in the new set-up: 10 Battalion PDF, which was now mooted as a citizen’s army of part-time volunteers who juggled day jobs as varied as doctors and lawyers to carpenters and hawkers, and who could be mobilised for support whenever the regular army needed reinforcement.

In 1967, the government introduced compulsory full-time national service. It realised that the cost of maintaining a sizeable full-time army of regular soldiers was too prohibitive, and relying on volunteers was not sustainable in the long term. Although the PDF was able to recruit as many as 3,200 volunteers by March 1966, the numbers petered out in subsequent years – the last intake in 1977 only saw 23 volunteers signing up. The writing was on the wall: 101 Battalion PDF (which had been renamed from 10 PDF Battalion in 1974) eventually disbanded in March 1984, bringing the curtain down on the history of the voluntary movement in Singapore.

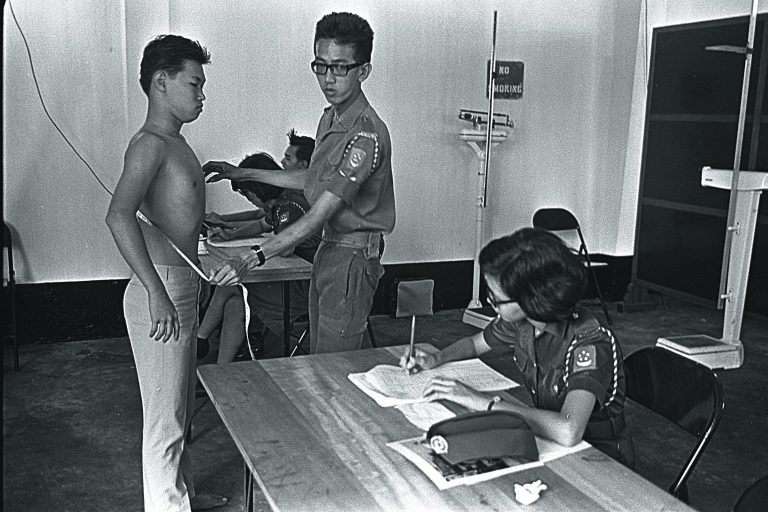

National Service registration exercise in 1967. A battery of pre-enlistment health checks were conducted to ensure that all new recruits were fit enough for the rigorous military training. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

National Service registration exercise in 1967. A battery of pre-enlistment health checks were conducted to ensure that all new recruits were fit enough for the rigorous military training. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Between 1965 and 2000,5 various units of the PDF and later, the Singapore Infantry Brigade (SIB), maintained a presence on Beach Road. From 1965–68 the camp hosted the 1st Training Depot PDF and HQ SIB; from 1968–74 HQ 1st SIB; from 1974–85, HQ PDF; and from 1985–2000 HQ PDF Command – and always training an assortment of army regulars, volunteers and national servicemen. Block 14 was used as the SAF Court Martial Centre for nearly 33 years, from 1967 to 2000. It housed the Subordinate Military Court as well as the higher Military Court of Appeal, and contained within its premises a courtroom, a deliberation room, witness rooms, a holding cell and various offices for the court staff and military prosecutors.

On 18 February 2000, in a moving ceremony that echoed its august colonial-era opening on 4 March 1933, the same Golden Key that British Governor Cecil Clementi was presented with 67 years ago at the very same Drill Hall was handed over to the SAF for final safekeeping. In the background, a solitary trumpet played the Last Post, signalling the end of the day – and indeed the end of an era for a distinguished Singapore institution.

One of the most famous SVC volunteers in the late 1950s was the war heroine Elizabeth Choy. Born in Sabah in 1910 and schooled in Singapore, Choy had a heightened sense of conscience since young. She gave up a college scholarship to work as a teacher to support her six younger siblings. During the Japanese Occupation, Choy and her husband worked tirelessly to smuggle medicine, money, letters and even radio parts to British civilians and prisoners-of-war interned at Changi Prison. Unfortunately, her husband was arrested in October 1943 and Choy herself a few weeks later. She was imprisoned and severely beaten by the Japanese over a 200-day period for being a British sympathiser. After the war, Choy was made Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) and became involved in politics and education, but it was her selfless work during the war that she is most remembered for.

Elizabeth Choy in a photo taken in 1955. Suspected of being an informant to the British during the Japanese Occupation, Choy was imprisoned and severely tortured over a 200-day period. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Elizabeth Choy in a photo taken in 1955. Suspected of being an informant to the British during the Japanese Occupation, Choy was imprisoned and severely tortured over a 200-day period. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

This is an abridged version of the chapter “1854–2001: History of Beach Road Camp and NCO Club” from the book *South Beach: From Sea to Sky: The Evolution of Beach Road* – written by Francis Dorai and published by Editions Didier Millet for South Beach Consortium in 2012. The S$3-billion South Beach development, designed by the British architectural firm Foster + Partners, was launched in December 2015 and comprises a luxury hotel, offices, apartments and retail space. The four conserved buildings of Beach Road Camp have been restored and blend with the modern structures: Block 1 houses bars and restaurants; Block 9 is the hotel ballroom; Block 14 is used as meeting rooms; and the NCO Club building has been turned into a private club for hotel guests.

Francis Dorai has worked for over two decades in publishing, both as writer and editor in a broad range of media, including The Straits Times, Insight Guides, Berlitz Publishing, Pearson Professional, Financial Times Business and Editions Didier Millet. He is the author of several books, including South Beach: From Sea to Sky: The Evolution of Beach Road.

Francis Dorai has worked for over two decades in publishing, both as writer and editor in a broad range of media, including The Straits Times, Insight Guides, Berlitz Publishing, Pearson Professional, Financial Times Business and Editions Didier Millet. He is the author of several books, including South Beach: From Sea to Sky: The Evolution of Beach Road.

REFERENCES

All set for the Singapore regiment. (1957, February 15). The Singapore Free Press, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Buckley, C.B. (1902). An anecdotal history of old times in Singapore. (2 Vols.). Singapore: Printed by Fraser & Neave. (RCLOS 959.57 BUC)

Gill, M.S. (1990, September). History of the Singapore Infantry Regiment, 1957–1967. The Pointer. (Call no.: RSING 355.005 P)

Koh, J.L., & Lo, M.H. (1993). Distinction: A profile of pioneers. Singapore: Second Singapore Infantry Brigade. (Call no.: RSING q356.189095957 KOH)

Makepeace W., Brooke, G.E., & Braddell, R.S.J. (Eds.). (1921). One hundred years of Singapore (Vol. I). London: J. Murray. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.51 MAK)

Savage, V.R., & Yeoh, B.S.A. (2013). Singapore street names: A study of toponymics. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions. (Call no.: RSING 915.9570014 SAV)

Singapore. Ministry of Defence. (2000). Lions in defence: The 2 PDF story. Singapore: Public Affairs Dept.: 2 PDF Command Officers’ Mess. Retrieved in BookSG.

Winsley, T.M. (1938). A history of the Singapore Volunteer Corps, 1854–1937: Being also an historical outline of volunteering in Malaya. Singapore: G. P. O. (Call no.: RCLOS 355.23 WIN)

NOTES

-

Makepeace W., Brooke, G.E., & Braddell, R.S.J. (Eds.). (1921). One hundred years of Singapore (Vol. 1, p. 377). London: J. Murray. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.51 MAK) ↩

-

Makepeace, Brooke & Braddell, 1921, Vol. 1, p. 247. ↩

-

Interview with Paul Cheah Thye Hong on 28 March 2012. ↩

-

All set for the Singapore regiment. (1957, February 15). The Singapore Free Press, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Beach Road Camp was handed over to the Urban Redevelopment Authority in late 2000. ↩