Bygone Brands: Five Names That Are No More

Sue-Ann Chia traces the birth and death of five companies, reliving the forgotten stories of some of Singapore’s biggest brand names.

In 1915, Whiteaways moved to its final location on Battery Road, right next to the General Post Office building that is today the Fullerton Hotel. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

In 1915, Whiteaways moved to its final location on Battery Road, right next to the General Post Office building that is today the Fullerton Hotel. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Do you remember Chung Khiaw Bank, Setron TVs and Three Rifles shirts? They were household brand names during their heydays and were very much part of the Singapore landscape. At their peak, many residents would have owned these products, used their services or at the very least, heard of these brands. Popularity, however, does not guarantee longevity. Over the years, the following five brands disappeared due to a variety of reasons, some more dramatic than others.

Whiteaway, Laidlaw & Co. (1900–62)

It was called the “Selfridges of the East”, the poshest chain of department stores this side of the Suez.1 Shoppers looking for high-end European products during the early 20th century would make a beeline for this iconic store – Whiteaway, Laidlaw & Co.

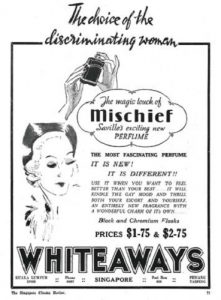

A Whiteaways advertisement in the 1937-38 issue of The Singapore Cinema Review introducing the “… exciting new perfume” called Mischief – all for the princely price of $1.75 or $2.75 a bottle. © The Singapore Cinema Review.

A Whiteaways advertisement in the 1937-38 issue of The Singapore Cinema Review introducing the “… exciting new perfume” called Mischief – all for the princely price of $1.75 or $2.75 a bottle. © The Singapore Cinema Review.Founded by two Scotsmen, E. Whiteaway and Robert Laidlaw, the first store was set up in Calcutta in 1882, where both men were based. Their business boomed, with branches sprouting in over 20 cities in India and the Straits Settlements (Singapore, Penang and Malacca), and in places such as Kuala Lumpur, Ipoh, Taiping, Seremban and Klang.2

The department store catered to Europeans living in these cities and affluent locals who could afford its pricey goods. Whiteaway, Laidlaw & Co. specialised in furnishings, haberdashery and tailoring as well as imported household items.

Whiteaways – as the chain was more commonly referred to – reached the shores of Singapore in November 1900. The store first opened its doors on D’Almeida Street at Raffles Place, purveying household goods, shoes and crockery. “In Singapore, as elsewhere, they have made a name for themselves as the leading drapers of the place… and their spacious showroom will best give an idea of the variety and immensity of the business,” said author Arnold Wright.3 The other two department stores in Singapore that offered similar luxury items and catered to the well-heeled were John Little’s and Robinson’s.4

When its Raffles Place lease ended in 1904, Whiteaways moved to a new building at the corner of Hill Street and Stamford Road. As the store was the main tenant, the new three-storey Oranje Building – renamed Stamford House in 19635 – was designed with Whiteaways’ requirements in mind.

Nine years later, in 1915, Whiteaways moved again to its final home on Battery Road, right next to the General Post Office building that is today the Fullerton Hotel. This time it owned the building, having bought the land where Flint Building – named after Captain William Flint, brother-in-law of Stamford Raffles – once stood. Flint Building, which housed the famous Emmerson’s Tiffin Rooms, was demolished following a major fire in 1906.6

The owners of Whiteaways purchased the land on a 50-year lease from the Flint family and developed a new four-storey building that was described as the most modern establishment in Singapore at the time. The store cost $300,000 to build and was designed along the lines of modern emporiums in London. It covered 12,200 sq ft of space and soared about 100 ft from basement to roof with beautiful display windows, lifts and steel structures.7

Around the time of the store’s opening, founder Robert Laidlaw – who lived 20 years in Calcutta before returning to England and becoming a Member of Parliament from 1906 until 1910 – died on 3 November 1915; he was 59. Knighted in 1909, Laidlaw was instrumental in growing the Whiteaways business empire. Not much is known about E. Whiteaway, the other founder, other than he used to work at another department store, Harrison and Hathaways, in Calcutta before setting up Whiteaways with Laidlaw.8

During World War II, the Japanese military took over the Whiteaways building and allowed the Japanese retailer Shirakiya – better known as Tokyu Department Store today – to use the premises. When the war ended, Whiteaways rebuilt its business at the same location. It managed to claw back its reputation as a premier shopping destination and held Singapore’s first fashion show on 3 November 1948.9

In 1957, Britain’s largest retailer, Great Universal Stores Ltd, acquired Whiteaways for nearly £600,000. It retained the directors and staff, and pledged to expand Whiteaways’ business in Singapore. But the opposite happened. Whiteaways abruptly closed in February 1962. The store manager cited the approaching termination of its land lease and poor trading results as reasons for the closure.10

The Whiteaways building was bought by Malayan Banking Limited (Maybank) for $1.4 million in October 1961 and used as its headquarters. It was demolished in 1997 to make way for the present 32-storey Maybank Tower.11

Chung Khiaw Bank (1947–72)

Set up by tycoon and philanthropist Aw Boon Haw – one half of the famous Haw Par brothers – Chung Khiaw Bank took pride in being the “Small Man’s Bank”, a bank for the ordinary man.

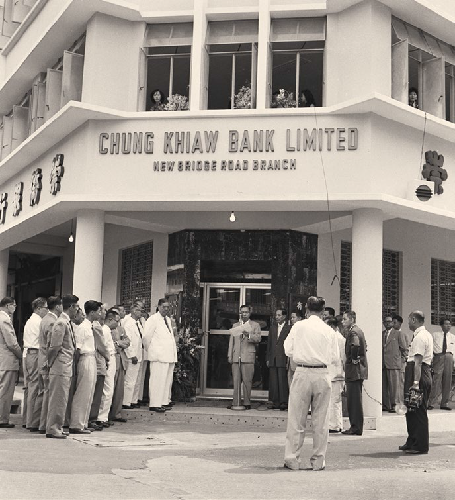

Opening of the New Bridge Road branch of Chung Khiaw Bank in 1957. Source: The Straits Times © Singapore Press Holdings Limited. Permission required for reproduction.

Opening of the New Bridge Road branch of Chung Khiaw Bank in 1957. Source: The Straits Times © Singapore Press Holdings Limited. Permission required for reproduction.Chung Khiaw Bank was incorporated in 1947 and started operations on 4 February 1950 on Robinson Road. Aw, dubbed the “Tiger Balm King” for building his family’s business empire from selling the trademark cure-all ointment, was the founder and first chairman of the bank’s board of directors, which included other prominent Chinese businessmen in Singapore.

Aw, who had moved from Burma to Singapore in the 1920s, had envisioned the bank as not only serving businessmen but all segments of society. “It is our intention to help the middle and lower classes – to give them a break… we will finance the small man, thus helping him, the community and the country,” he said in an interview with The Straits Times before the bank opened in February 1950.12

When Aw died in 1954 at age 71, Chung Khiaw Bank was placed in the good hands of his nephew-in-law Lee Chee Shan, who was credited with making the bank a household name in Singapore.

The bank started with an authorised capital of $5 million and paid-up capital of $2.5 million. By 1971, it was Singapore’s second largest local bank in terms of assets. The bank had a total of 32 offices – 14 in Singapore, 16 in East and West Malaysia and two in Hong Kong – and ambitious expansion plans in the pipeline.13

Chung Khiaw’s unique reputation as a small man’s bank was the backbone of its success. The bank proved that it did not need the patronage of the wealthy for business to be lucrative. Over the years, its clientele included small traders, labourers and even students under 12 years old. “No customer is too small, and no account is too big” was the motto of the bank.14

The bank was the first to introduce several innovative ideas to keep ahead of the competition. Lee Chee Shan’s philosophy was “little drops make a mighty ocean”. In 1956, the bank printed promotional pamphlets in the four main languages – English, Chinese, Malay and Tamil – departing from the usual practice of only targeting a particular Chinese dialect group. All this was part of its plan to encourage the public to make banking a greater part of their lives. The bank also launched mobile banking, literally a bus that drove to six rural areas regularly to bring banking facilities to the doorsteps of villages.15

Baby boomers will remember the coins bank which was introduced in 1958 specifically for children. It encouraged children to save by issuing metal “piggy” banks that later morphed into other animal shapes such as rhinocerous, camel, elephant and squirrel. Within two years, the bank received an astounding $3.5 million in coin deposits from children.16

Chung Khiaw Bank was ahead of the curve in many ways. Another pioneering move was the “Lady in Pink” service, started in June 196217 to woo women to open bank accounts. There was even an “All Ladies Bank” – a sub-branch opened in August 1963 in Selegie House that was manned entirely by female staff.18 The bank encouraged women to join its workforce at a time when banking was still the traditional preserve of men. A “good number” of its top executives were women and Chung Khiaw has been credited for opening up careers in banking for women in the region.19

The bank’s run of good fortune came to an end shortly after it celebrated its 21st anniversary in 1971. Aw Cheng Chye, nephew of the late Aw Boon Haw who took over the family business when the latter died, had earlier listed the business, which included Tiger medicinal products, newspaper publishing and Chung Khiaw Bank, as Haw Par Brothers International.

On 4 June 1971, news emerged that Aw had sold a substantial stake in the company to Slater Walker Securities of the UK, giving the latter a majority holding of slightly more than 50 percent in Haw Par. Two weeks later, Slater Walker Securities sold 49.8 percent of Chung Khiaw Bank’s equity to United Overseas Bank (UOB) for $22 million.20

In August that year, the managing director Lee Chee Shan retired from his position, saying that he wanted to give way “to a young and dynamic leadership”.21 A year later, UOB completed its takeover of Chung Khiaw Bank. In 1999, UOB merged its Chung Khiaw bank subsidiary to rationalise operations. In one fell swoop, the name Chung Khiaw Bank was erased forever.

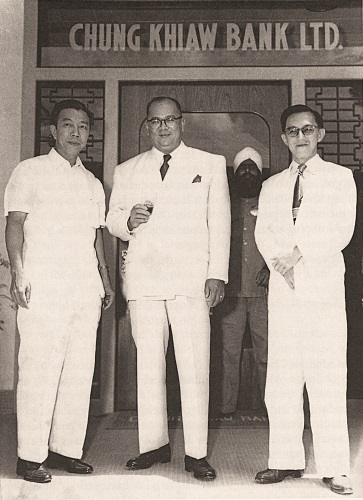

Managing Director Lee Chee San (centre) with friends at the opening of the Tiong Bahru branch of Chung Khiaw Bank in 1958. All rights reserved, Yeap, J. K. (1994). Far from Rangoon: Lee Chee San 1906–1986. Singapore: Lee Teng Lay.

Managing Director Lee Chee San (centre) with friends at the opening of the Tiong Bahru branch of Chung Khiaw Bank in 1958. All rights reserved, Yeap, J. K. (1994). Far from Rangoon: Lee Chee San 1906–1986. Singapore: Lee Teng Lay.As for the Haw Par family fortune that was reportedly worth hundreds of millions, it did not last beyond the second generation. Aw Cheng Chye died in August 1971, a few months after selling Haw Par to Slater Walker Securities. After a series of bad investments by other family members, the money was whittled away. Matriarch Aw Cheng Hu, the niece of founder Aw Boon Haw – and the widow of Lee – was said to be living in a rented four-room HDB flat in Sengkang a few years before her death in 2010.22

Today, banking giant UOB not only owns Chung Khiaw Bank, but also Haw Par Corporation (formerly Haw Par Brothers International) and the Tiger Balm brand.

Setron TV (1964–86)

The first ever Singapore-assembled black-and-white TV set rolled off the production line at local enterprise, Setron Limited, in September 1965. Television in Singapore had just been introduced in February 1963,23 and given the small number of households that owned a TV set at the time – most people watched TV at their local community centres – this was a business that showed plenty of promise.

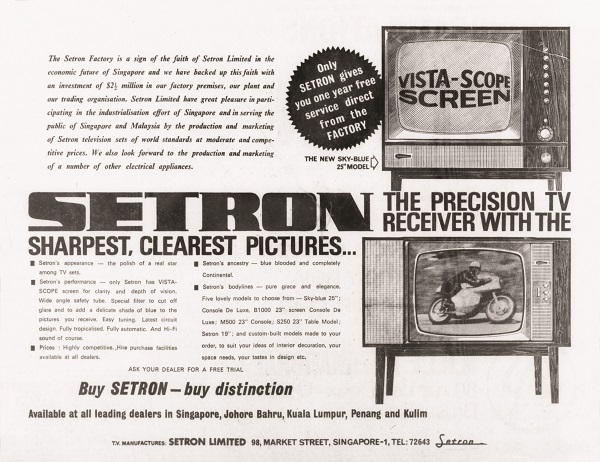

Newspaper advertisements by Setron such as this one in the 28 April 1966 issue of The Straits Times touted the latest in techonology, like the “Vista-Scope Screen”, and claimed that its TV screens provided the “sharpest, clearest pictures”. © The Straits Times.

Newspaper advertisements by Setron such as this one in the 28 April 1966 issue of The Straits Times touted the latest in techonology, like the “Vista-Scope Screen”, and claimed that its TV screens provided the “sharpest, clearest pictures”. © The Straits Times.The idea of a made-in-Singapore TV set seemed preposterous at the time, but Setron managed to pull it off. With component parts imported from Belgium, Setron TV – encased in classic teak cabinets with shutters enclosing the screen – became a fairly commonplace item in many households by the 1970s. It was not unusual for proud owners to drape their TV sets with decorative cloths and use the top as a display shelf for framed photographs and other home knick-knacks.

Founded in 1964 by a group of enterprising local businessmen led by Tan Sek Toh, Setron was granted pioneer status by the government as it was the first electronics plant in newly industrialising Singapore. After its formation, Setron immediately started a training programme for its technical staff with assistance from MBLE International of Belgium, which supplied the component parts to Setron’s local plant.24

A year of intensive training later, the company began operations at its temporary premises on Leng Kee Road while constructing its own factory at Tanglin Halt. Production began in September 1965 and Setron TV sets were sold just three months later in December.25

Setron started by assembling 400 sets a month, with plans to ramp it up to as many as 2,000 sets a month in addition to other electronic products such as tape recorders and transistor radios once it moved to a bigger factory. In April 1966, Setron relocated to its new 80,000-sq-ft factory at Tanglin Halt, with air-conditioned workshops and a 96.5-ft-tall central tower that was used for advertisements.26

At the opening of the $1.5 million factory, then Minister for Finance Lim Kim San said: “The idea of producing television sets in Singapore, I think, appears to some people to be extravagant hope. I believe this will come about eventually just as television is now a fact. Television – the transmission of images through the air – was an extremely unlikely idea to most people before it became a reality.”27

By 1966, one in six local households owned a TV set in Singapore, one of the highest penetration rates in the region.28 That same year Setron rolled out more models, including a “25-inch luxury television set and a 19-inch economy model”. Newspaper advertisements touted the latest in techonology, like the “Vista-Scope Screen” and claimed that its TV screens provided the “sharpest, clearest pictures”.29 Setron TV sets cost between $859 and $968 each, according to an advertisement in 196630 – which was no small change at the time – competing with higher priced imported brands such as Philips, Normende, Grundig and Telefunken.

In 1967, Setron started to assemble other brands of TV sets like National and Sanyo. Philips, Siera and Nivico models were added in 1968. By 1971, Setron was a listed company and had become the largest television manufacturer in Southeast Asia. It also produced radiograms (a combination radio and record player), amplifiers and other electronic equipment, with products exported to Malaysia, Mauritius, Cambodia, Vietnam, Africa and the Philippines.31

Under the leadership of Setron’s founder and first chairman Tan Biauw, a well-known business personality who was a director at United Overseas Bank (UOB), the company set up joint ventures with foreign companies and associated companies in Singapore, including local brand Acma which manufactured refrigerators and air-conditioners. Many older Singaporeans would have grown up in households that had an Acma fridge – another Singapore success story. UOB’s Wee Cho Yaw took over as Setron chairman around 1971.32

In April 1979, Haw Par Brothers International – owned by UOB and whose chairman was also Wee – made a bid to acquire Setron which by then also distributed Sony products. In July, Haw Par successfully took over Setron, controlling 60 percent of its shares. Setron’s managing director, Tan Sek Toh, emigrated to Canada after selling his stake in the company. 33

Setron continued to manufacture TV sets until the 1980s. In 1986, it became a subsidiary of Sony Corporation Japan and was renamed Sony Singapore.34 Its Tanglin Halt factory is now the site of Haw Par Corporation – the former Haw Par Brothers International.

Three Rifles Shirt Co. (1969–2006)

Many Singaporeans grew up with the trademark Three Rifles shirt, worn by their husbands, fathers or even grandfathers. It was set up by Chong Chong Choong, who left his Kuala Lumpur hometown at age 14 to strike out on his own in Singapore as an apprentice selling shirts and textiles.35

Three Rifles Shirts billed its shirts as “the distinctive shirt for the distinguished man about town” in this advertisement dated 19 April 1980 in the New Nation. © New Nation.

Three Rifles Shirts billed its shirts as “the distinctive shirt for the distinguished man about town” in this advertisement dated 19 April 1980 in the New Nation. © New Nation.Five years later, in 1955, at age 19, Chong opened his first shop in Bukit Panjang selling shirts from different brands. It was just half a shop space, bought at a princely sum of $7,000 – his hard-earned savings. Business was brisk; in just four years, his half shop had expanded into one full shop space. He stayed in that location for another 10 years, until 1969 when he opened a store at The President, one of Singapore’s first shopping centres (today renamed Serangoon Plaza).36

With the move to a swanky new location, Chong decided to stop selling shirts made by others and produce his own label instead. He employed a part-time designer and 10 workers, and started the Three Rifles Shirt Manufacturing Company. Although the company produced around 1,200 shirts a month, demand soon outstripped supply. Chong needed to expand – fast.

Before opening his first factory in Geylang in 1971, Chong visited shirt factories in Hong Kong, Japan and Europe to get new ideas and contacts of textile manufacturers. Four years later, in 1975, he acquired his second factory at MacPherson. In the meanwhile, he had opened the first Three Rifles shop at People’s Park Complex in 1972. Two other shops within the same premises followed, then another at People’s Park Centre next door, at Peninsula Plaza, at Katong Shopping Centre and at Thomson Plaza.37

By 1981, Three Rifles was worth $4.5 million. Chong had seven retail shops in Singapore, agencies in Indonesia selling his shirts and was looking to break into the European market to compete with established brand names such as Lanvin and Pierre Cardin. His foray into Indonesia selling high-quality shirts was so successful that 40 percent of the shirts produced were sold there in the 1970s and 80s. Again, with rising demand, Chong needed to expand his production. And again, he looked overseas for inspiration.38

This time, Chong bought machines that would automate the entire shirt manufacturing process – allowing his factory to produce more, and faster. There was even a machine just to embroider the Three Rifles logo on every shirt. Besides manufacturing its own brand of clothing, Three Rifles also imported clothing brands such as Lonner, Portfolio and Rhomberg. The company became the regional manufacturer for Emporio Armani, and from 1980, the regional representative for Italian fashion label Caserini.39

In the mid-1990s, Chong began to diversify his business. He branched into commercial and residential property development in Singapore and Malaysia with the formation of Three Rifles Land.40 In 1998, sister company TR Networks, which sold beauty and lifestyle products, was established with Chong as chairman and his son-in-law Ting Yen Hock as chief executive.41 In 2005, Three Rifles was bought over by TR Network,42 and in the following year, Three Rifles International – now a subsidiary of TR Networks – signed a licence agreement with French designer brand Pierre Balmain to manufacture menswear under the brand and sell them in Singapore and Brunei. Within just three months, Three Rifles opened three counters to sell Pierre Balmain clothes at Robinsons and Isetan Scotts in Singapore.43

As far as we can ascertain, the Three Rifles brand does not exist anymore, and all its stores in Singapore have since closed down.

Thye Hong Biscuit & Confectionary Company (1929–90)

The signature bronze lion and flame-lit torch on top of Thye Hong Biscuit and Confectionary factory at the junction of Alexandra Road and Tiong Bahru Road was a defining landmark in the area at one time. Although the factory began operations in 1935, Thye Hong had been set up earlier in 1929 at 124 Neil Road.44 It was owned by Lee Gee Chong, son of leading banker Lee Choon Seng and the former chairman of the Oversea-Chinese Banking Corporation.

As business grew, the younger Lee built a bigger factory on Alexandra Road at a cost of $250,000. The plant could produce 10–12 tonnes of biscuits daily under hygienic conditions – with the biscuits untouched by human hands. Thye Hong biscuits continued to gain in popularity. In 1952, the company stepped up production with a massive 18-month expansion programme that would increase biscuit production to 1,500 tonnes and confectionary production to 100 tonnes every month.45

Then Minister for Social Affairs Othman Wok (extreme left) visits the factory of Thye Hong Biscuit in 1975. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Then Minister for Social Affairs Othman Wok (extreme left) visits the factory of Thye Hong Biscuit in 1975. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.However, tragedy struck on 20 April 1960. Lee, who had become famous as the “Biscuit King”, was ambushed near his Garlick Avenue home while being driven home by his driver. After Lee’s car was forced into an embankment by another car, three men pulled him out of the vehicle and abducted him. His injured driver was left alone. Five days later, Lee’s body was found wrapped in a blanket and left in a graveyard off Yio Chu Kang Road.46

Further tragedy awaited the family: five years later, in 1965, his son Lee Boon Leong who had taken over the reins at Thye Hong, was shot by armed gangsters in a kidnap bid while he was driving alone along dimly-lit Geylang Lorong 20.47 Fortunately, he underwent an emergency surgery and survived.

Meanwhile, Singapore-made biscuits were “crumbling against the wall of local prejudice”, according to a media report in 1965. Its production declined while that of foreign biscuits imports rose, even though the latter was more expensive. Biscuit bosses blamed several factors, from the on-going Konfrontasi (or Confrontation, 1963–66) with Indonesia closing off a lucrative market to new duties imposed by Malaysia. Foreign packaging was also nicer, they acknowledged.48

Yet, Thye Hong appeared to be going strong. In 1964, it was reported that Thye Hong’s biscuits were served on board Malaysian Airways flights, an indication of its upmarket image. Its factory in Singapore had modern machines, with a staff of over 200 – many of whom were trained by foreign biscuit experts.49 Thye Hong also had another factory in Johor.

Singaporeans growing up in the 1960s and 70s will remember eating popular Thye Hong goodies such as Marie, Cream Crackers and Horlicks biscuits. One of its specialities was the Jam De Luxe biscuit, a rich shortcake biscuit sandwich with sticky pineapple jam in between.50

In 1971, one of Britain’s largest biscuit manufacturers, Huntley and Palmer, entered into an agreement with Thye Hong to produce part of its range of sweet and semi-sweet biscuits in Singapore and Malaysia – under the British firm’s subsidiary Associated Biscuits.51

Biscuit tin and paper bag of Thye Hong Biscuit & Confectionery Company from the 1950s. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

Biscuit tin and paper bag of Thye Hong Biscuit & Confectionery Company from the 1950s. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.A decade later, in late 1981, Associated Biscuits (Huntley and Palmer) bought Kuan Enterprises, which owned Thye Hong Singapore and Malaysia, for $12 million. With this, the familiar torch and lion trademark on the roof of the factory disappeared when the factory closed down. The site was redeveloped into an office building – Thye Hong Centre – by Thye Hong Properties and Thye Hong Development, set up in 1981 by Lee Boon Leong and his mother, Madam Tay Geok Yap. New chairman and chief executive of Kuan Enterprises Julian Scott said the company would expand the range of products under Thye Hong. Its trademark would be retained and the old emblem would be part of the new factory complex in the western part of Singapore.52

Thye Hong biscuits continued to be sold, although the brand ownership changed hands over the years. Associated Biscuits was acquired by American company Nabisco in 1982 and was eventually bought by Britannia Brands – set up by former Nabisco executive Rajan Pillai – which also owned other Nabisco brands such as Jacob, Ole and Planters.53

In 1990, Pillai struck a deal with France’s biggest food company BSN Groupe to purchase Nabisco operations in Singapore, Malaysia, Hongkong and New Zealand for US$180 million.54

Sue-Ann Chia is a journalist with over 15 years experience covering politics and current affairs at various newspapers, including The Straits Times and Today. She is currently the Associate Director at the Asia Journalism Fellowship and a Director at The Nutgraf, a boutique writing and media consultancy.

Sue-Ann Chia is a journalist with over 15 years experience covering politics and current affairs at various newspapers, including The Straits Times and Today. She is currently the Associate Director at the Asia Journalism Fellowship and a Director at The Nutgraf, a boutique writing and media consultancy.

NOTES

-

Das, S. (2008, July 1). A brief history of shopping. The Telegraph. Retrieved from The Telegraph India website. ↩

-

Vedamani, G. G. (2003). Retail management. Mumbai: Jaico Publishing House. Retrieved from Google Books; National Library Board. (2006). Whiteaway Laidlaw written by Chia, Joshua Yeong Jia. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia. ↩

-

Wright, A., & Cartwright, H. A. (Eds.). (1908). Twentieth century impressions of British Malaya: Its history, people, commerce, industries, and resources (p. 689) London: Lloyd’s Greater Britain Pub. Call no.: RCLOS 959.51033 TWE ↩

-

National Library Board, 2006. ↩

-

National Library Board, 2006; Singapore. Urban Redevelopment Authority. (n.d.). Capitol Theatre, Capitol Buildng and Stamford House. Retreived from Urban Redevelopment Authority website. ↩

-

Maybank. (1998, November 27). Background information on site of Maybank headquarters in Singapore. Retrieved from Maybank website. ↩

-

Whiteaway Laidlaw. (1915, May 31). The Straits Times, p.10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The late Mr Robert Laidlaw. (1915, November 5). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Vedamni, 2003. ↩

-

National Library Board, 2006; Warm work for mannequins. (1948, November 4). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

‘Gussies’ chief here, plans expansion. (1957, December 14). The Straits Times, p. 9; Whiteaway Laidlaw to close in Singapore. (1961, December 28). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Whiteaway building sold for $1.4million. (1961, December 30). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Maybank. (1998, November 27). Ground breaking ceremony for Maybank headquarters in Singapore. Retrieved from Maybank website. ↩

-

New bank will aid the small man. (1949, December 30). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 30 Dec 1949, p. 7; Steady progress all through the years. (1971, February 4). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 4 Feb 1971, p. 6. ↩

-

Leo, S. (2012). (Ed.). Southeast Asian personalities of Chinese descent: A biographical dictionary (Vol. 1, p.497). Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. Call no.: RSING 959.004951 SOU ↩

-

The $3.5 million success story of Singapore’s ‘piggy’ bank. (1960, February 7). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Another venture from a family of pioneers. (1963, March 2). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Another first’ in banking world: An all-woman staff. (1963, August 24). The Straits Times, p. 15; All ladies bank a success. (1966, May 16). The Straits Times, p. 16. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 4 Feb 1971, p. 6. ↩

-

Johnson, B. (1971, June 5). Haw Par: UK firm acquires big stake. The Straits Times, p. 1; Johnson, B. (1971, June 18). It’s a deal: $22m cash! The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Retired head of Chung Khiaw to run insurance companies. (1971, August 3). The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Dato Aw dies during visit to Chile. (1971, August 24). New Nation, p. 1; Raymond, J. (2002, December 5). Tiger Balm’s poor old lady. Today, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Raja to launch Singapore TV. (1963, February 13). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lim, B. T. (1966, April 28). First Singapore electronics factory. The Straits Times, p. 15. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times , 28 Apr 1966, p. 15. ↩

-

Television assembly factory plans further extension. (1965, December 4). The Straits Times, p. 29. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; The Straits Times, 28 Apr 1966, p. 15. ↩

-

Company farsighted. (1966, April 28). The Straits Times, p.15. Retrieved from NewspaperSG ↩

-

One home in six has TV. (1966, April 26). The Straits Times, p. 15. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Page 15 Advertisements Column 1: Setron. (1966, April 26). The Straits Times, p. 15. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ho, A. L. (2015, May 24). Setron, a bright spark in troubled times. The Sunday Times, p. 42. Microfilm no.: NL 33501 ↩

-

Setron: Five years of steady growth. (1971, April 28). The Straits Times, p. 20. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times , 28 April 1971, p. 20; Bankers, businessmen among board members. (1971, April 28). The Straits Times, p. 20. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Sunday Times, 24 May 2015, p. 42. ↩

-

The Sunday Times, 24 May 2015, p. 42. ↩

-

Seah, R. (1981, February 3). A good shot in the right direction. The Business Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Business Times , 3 Feb 1981, p. 6. ↩

-

The Business Times , 3 Feb 1981, p. 6. ↩

-

The Business Times , 3 Feb 1981, p. 6. ↩

-

National Library Board. (2016). Three Rifles Holdings is established. Retrieved from HistorySG. ↩

-

Tan, C. (1997, September 29). Three Rifles sets its sights on property development. The Straits Times, p. 48. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Yap, S. (2003, April 3). TR Networks expanding market into Singapore. The Business Times. p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Goh, E. Y. (2005, January 11). TR Networks buys Three Rifles. The Straits Times, p. H17. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Khin, N. (2006, November 23). Three Rifles looks to open Balmain store in Singapore. The Business Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

National Heritage Board. (2015, July 2). Thye Hong Centre. Retrieved from National Heritage Board website; $250,000 biscuit plant in Singapore. (1935, March 27). The Straits Times, p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times , 27 Mar 1935, p. 13; 1,500 tons of biscuits every month. (1952, November 11). The Straits Times, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ee, B. L. (1960, April 25). Kidnap: Body found. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Cheong, Y. S. (1965, July 23). Biscuit king’s son shot. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Soh, T. K. (1965, December 12). Pride and prejudice. The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lee, G. (1964, October 28). Local biscuits and sweets measure up to world standard. The Straits Times, p. 52. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times , 28 Oct 1964, p. 52. ↩

-

English biscuits to be made locally. (1971, June 23). The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

British firm buys up Thye Hong. (1982, January 12). The Straits Times, p. 8, Lee, Y. M. (1981, September 23). Thye Hong ventures into property. The Straits Times, p. 15. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Tripathi, S. (1993, March 12). A year of nightmares for biscuit king. The Business Times, p. 10; Lee, H. S. (1990, March 9). French dough creates new biscuit giant. The Business Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Business Times , 9 Mar 1990, p. 1. ↩