The Fruit of His Labour: David Marshall’s Old Apple Tree

Singapore’s fiery Chief Minister used to hold court under an apple tree at Empress Place. But was it really an apple tree? Marcus Ng separates fact from fiction.

David Marshall addressing the lunchtime crowds under the “old apple tree” at Empress Place in 1956. Source: The Straits Times © Singapore Press Holdings Limited. Permission required for reproduction.

David Marshall addressing the lunchtime crowds under the “old apple tree” at Empress Place in 1956. Source: The Straits Times © Singapore Press Holdings Limited. Permission required for reproduction.David Saul Marshall (1908–95), who was born into a Jewish family of Iraqi origins in Singapore, rose to fame as the nation’s first Chief Minister. He led a government that lasted a mere 14 months from 6 April 1955 to 7 June 1956. The brevity of his term – an anomaly given the subsequent dominance of the People’s Action Party (PAP) – belies the symbolic break from the past that Marshall’s office represented as well as the constitutional legacy that defined his tenure.

A successful criminal lawyer before he was “thrust into politics by a sense of outrage, [and] a deep sense of anger”1 towards colonial rule and its associated injustices, Marshall’s electoral success as part of the Labour Front represented a clear departure from a political landscape that had endured 136 years of rule by fiat.

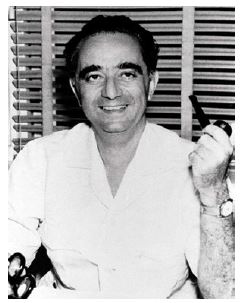

David Marshall in a photo taken in the 1950s. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

David Marshall in a photo taken in the 1950s. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Singapore’s first polls, in 1948 and 1951, had involved no more than a scant 2 to 3 percent of the population2 and admitted a handful of subjects to a Legislative Council dominated by the British Governor, Franklin Charles Gimson, and his peers. The general election of 2 April 1955, however, paved the way for Singapore’s first real brush with a parliamentary democracy. Held under the Rendel Constitution3 that gave Singapore partial internal self-rule, the 1955 polls involved more than a quarter4 of the population of 1.14 million, who voted for 25 representatives in a 32-seat Legislative Assembly. The winning party or coalition with a majority in the assembly would form a council of ministers with control over all portfolios except for external affairs, finance, internal security and defence, which were to remain in British hands.

Thanks to automatic voter registration which enfranchised a hitherto indifferent segment of the population, the 1955 election did more than just unleash a political floodtide. The results stunned the British, who had expected a comfortable romp home by the Progressive Party, a middle-class group who preferred gentle reform to rapid independence. Instead, the Labour Front headed by Marshall, a belligerent leftist coalition firmly in favour of the latter path, plus merger with Malaya to boot, found itself sharing power with Governor John Fearns Nicoll5 (who succeeded Gimson in 1952), a man who was clearly uncomfortable with the outright cries for merdeka (freedom) in the august Chamber of Assembly House (later renamed Parliament House) and outside of it.

An Office Under the Stairwell

Marshall’s first days as Chief Minister set the tone for the most part of his term. Much has been made of his famous feud with Nicoll, who had assumed that Marshall would use an office in the Ministry of Commerce and Industry at Fullerton Building6 across the Singapore River, as Marshall also held this portfolio. Outraged that Assembly House offered no office space for the Chief Minister, Marshall threatened to set up a chair and table “under the old apple tree” at Empress Place.

To avoid embarrassment, Chief Secretary William Goode hurriedly carved up a makeshift “cubby-hole”, under the staircase7 an “office” that Marshall described as being “not more than about 14 foot long by about 12 foot wide” with “one lamp, one table, two chairs, one calendar”. Marshall occupied this space, working in full view of all visitors to the Assembly House, for about a month until a general office and private quarters were prepared for him upstairs.8

The Old Apple Tree

But what of the “old apple tree”, a landmark that had become synonymous with Marshall as his preferred site for campaign speeches during the 1955 election, and where the Chief Minister addressed the people directly at rousing lunchtime rallies?

This tree served as an emblem of sorts for Marshall when he launched a political campaign in March 1955 that ended in a landslide win that few (and likely not even Marshall himself) expected. Choosing a spot by the river where Stamford Raffles first landed and flanked by the Government Offices at Empress Place – the headquarters of the Colonial Secretary, the British official who was second-in-command to the Governor – Marshall made his pitch for the Cairnhill ward. Standing under the shade of “the old apple tree”, Marshall could not have chosen a better spot right in the heart of colonial Singapore to drive home his message of anti-colonialism with a socialist face.

It probably made sense for Marshall to stand beneath a sizeable tree to command his lunchtime audience. The shade would have given respite from the midday heat and encouraged the crowd to huddle under the shadow cast by the branches against the noontime sun. The resulting scenes, according to Marshall’s biographer Kevin Tan, “electrified the political stage”.

The public had never “seen anyone as charismatic, as vocal, and as trenchant in his criticism of the colonial authorities”.9

Goode, who succeeded Nicoll in 1957 as the last colonial Governor and later served as Singapore’s first Yang di-Pertuan Negara, was himself captivated by Marshall’s soapbox. He recalled in an interview in 1971:

“One of his favourite meeting places was a tree outside the front of the government offices in Empress Place. At his lunch-time meetings there ‘under the old apple tree’, he used to make the most absorbing exciting speeches, directed to some extent to the government officers who flocked out in their lunch hour to listen to him.”10

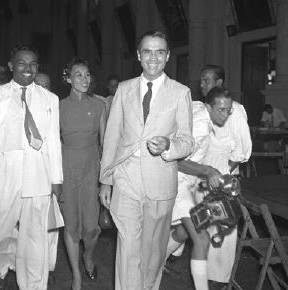

Chief Secretary William Goode (centre) at the Victoria Memorial Hall on nomination day for the 1955 Legislative Assembly general election. Goode, who later became Governor and Singapore’s first Yang di-Pertuan Negara, was captivated by the fiery speeches that Marshall made under the “old apple tree”. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Chief Secretary William Goode (centre) at the Victoria Memorial Hall on nomination day for the 1955 Legislative Assembly general election. Goode, who later became Governor and Singapore’s first Yang di-Pertuan Negara, was captivated by the fiery speeches that Marshall made under the “old apple tree”. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.When the election results were announced, Marshall’s Labour Front emerged as the clear frontrunner with 10 seats, while the pro-British Progressive Party was in tatters, with just four seats. After learning of his triumph over the Progressive Party leader C. C. Tan, Marshall declared:

“I believe the landslide to Labour was born under that old tree in Empress Place. Now they can see who is the political baby. How I am enjoying this moment of victory. They laughed and sneered at me when I talked under the old apple tree at Empress Place.”11

The Chief Minister and his cabinet – Minister for Communications and Works Francis Thomas, Minister for Local Government Abdul Hamid bin Haji Jumat, Minister for Education Chew Swee Kee, Minister for Health Armand Joseph Braga and Minister for Labour and Welfare Lim Yew Hock – were sworn in on 6 April 1955. Marshall then took the added step of presenting his team to the people under “the old apple tree”,12 proclaiming the line-up as “your Government” and pledging to work for “the welfare of the people of Singapore”.

(Left) David Marshall welcoming the new Governor, Sir Robert Brown Black, at Kallang Airport on 30 June 1955. In the background are Chief Secretary William Goode and Lady Black. David Marshall Collection, courtesy of ISEAS Library, ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore.

(Left) David Marshall welcoming the new Governor, Sir Robert Brown Black, at Kallang Airport on 30 June 1955. In the background are Chief Secretary William Goode and Lady Black. David Marshall Collection, courtesy of ISEAS Library, ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore.The tree served as Marshall’s totem of authority. But it was also a platform for resistance. The Chief Minister’s trademark bush jacket and pants – a sartorial affront to the morning suit that was de rigueur for government ministers – stemmed from a campaign promise made under the “apple tree” that he would “go in as I am”.13 That the Governor was aghast at Marshall’s lack of decorum only encouraged him further. Marshall’s colleague Francis Thomas took this up a notch by turning up for Legislative Assembly sittings in a safari jacket and sandals without socks – which exposed his ankles and provoked an audible gasp in the Chamber.

GORA SINGH AND HIS ROASTED SHEEP

Marshall did not enjoy a total monopoly over the tree. On 25 July 1955, Gora Singh, a wrestler from India, planned a public demonstration of his eating prowess under “the old apple tree” involving the gobbling down of an entire roasted sheep. The attempt, which actually began at the steps of the Dalhousie monument, was unsuccessful as the wrestler was mobbed by the crowd before he could finish his meal.14 It is not known if Singh suffered from severe indigestion as a result of this aborted feat.

A Sensation of Merdeka

Before his first year was up, Marshall had made good on his promise to fight for selfgovernment. To relieve the workload of his cabinet, Marshall had asked Governor Robert Brown Black (who succeeded Nicoll on 30 June 1955) on 4 July that year to appoint three junior ministers. Marshall believed the Governor was constitutionally obliged to do so but Black thought otherwise. An administrative deadlock quickly turned into a full-blown constitutional crisis as Marshall threatened to resign and force new elections.15

An emergency session of the Legislative Assembly was held on 22 July, during which Marshall read a motion calling on the British to “grant self-government at the earliest possible moment”. This motion was seconded by Lee Kuan Yew, then leader of the opposition PAP, and passed with near unanimity in the Chamber.16

As the Chief Minister’s manoeuvres, which marshalled a united front against British intransigence, gave the Colonial Office little wiggle room, it was forced to agree to an accelerated timetable towards merdeka. All-party talks for a self-governing Singapore were scheduled for April 1956. In the run-up to the talks in London, Marshall continued to press the point through Merdeka Week, an island-wide campaign in March that included an informal referendum, rallies and thousands of posters, including one stating “Singapore wants Merdeka”.17 Marshall personally hammered this last poster into the “apple tree”, which he likened to “the first nail into the colonial coffin.” The poster, alas, was pilfered, prompting Marshall to say: “They can steal our posters but they cannot alter our feelings.”18

Marshall resigned as Chief Minister on 7 June 1956 after the constitutional talks in London broke down over the issue of a joint defence and internal security council. “Christmas pudding with arsenic sauce”, was his acerbic verdict of the British’s final offer of a council with a British veto.19 Marshall’s successor Lim Yew Hock, who broke this impasse by offering the council’s casting vote to a Malayan delegate (with the blessing of Malaya’s premier Tunku Abdul Rahman), would win self-rule for Singapore but ultimately had to step down in 1959, having lost the popular vote for his overt suppression of leftist students and unionists.20

Marshall regarded Lim’s constitutional achievement as a “fraud” and resigned from the Legislative Assembly on 30 April 1957, triggering a by-election for Cairnhill. At least one candidate saw the “apple tree” as a mantle of sorts during the contest for Marshall’s former ward. M. A Majid, an independent, held a lunchtime meeting under it on 27 May 1957 but fled, along with his audience of 20, to shelter when rain wrecked his act. A second attempt to rally his troops a day later was foiled when the police informed Majid that his rally site was not part of Cairnhill ward.21

During the 1959 general election for a fully elected Legislative Assembly, the PAP sought to tap on the still-resonant symbolism of the tree. But they were denied permission to hold a rally under it – public gatherings on the left bank of the Singapore River had been prohibited whenever the Legislative Assembly or Supreme Court was in session.22 The PAP shrugged off this hiccup and instead held its rally across the river at Fullerton Square, a tradition that continued in the decades to come.

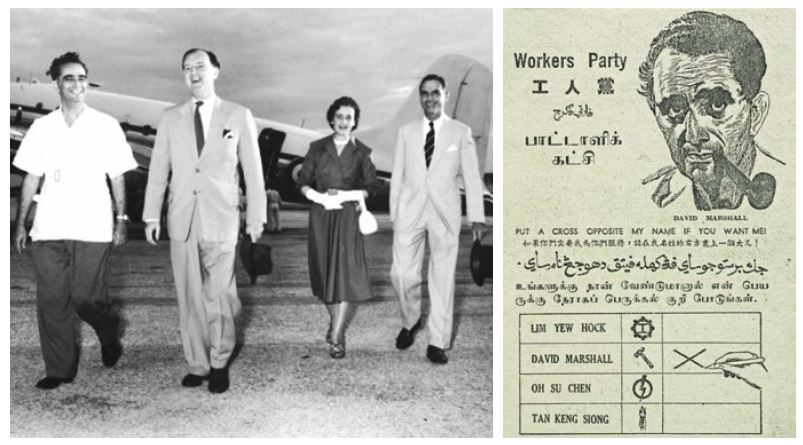

Meanwhile, Marshall, who had founded the Workers’ Party on 7 November 1957 and was once again contesting Cairnhill, was reported to have “deserted his old apple tree, and… canvassing quietly from house to house”. Indeed, as The Straits Times had declared earlier on 26 February 1957, following Marshall’s ouster from leadership in the Labour Front, “The season of the old apple tree is over”.23

David Marshall and his British-born wife Jean with two of their three daughters, Joanna and Ruth, in their arms respectively in a photo taken in January 1964. Courtesy of Mrs Jean Marshall.

David Marshall and his British-born wife Jean with two of their three daughters, Joanna and Ruth, in their arms respectively in a photo taken in January 1964. Courtesy of Mrs Jean Marshall.A TREE BY ANY OTHER NAME

Was there really an apple tree at Empress Place? It doesn’t take a botanist to tell you that apple trees (Malus domestica) do not thrive in Singapore’s equatorial climate. The genus Malus consists of deciduous fruit trees that flourish only in the temperate zones, with southern China forming the southernmost natural limit. A real apple tree at Empress Place, even if it did not bear flowers and fruit due to the lack of seasonal triggers, would have likely attracted almost as much attention as Marshall himself, given the visual contrast to nearby vegetation and the tree’s natural tendency to shed all leaves periodically. Could Marshall’s tree have been the Malay rose apple tree (Syzygium malaccense) that is native to Southeast Asia? This tree, also known to locals as jambu bol or jambu merah, was commonly cultivated in compounds for its edible fruit, which attract animals such as fruit bats, squirrels and birds.24 The rose apple is not usually planted as a roadside tree though, as its profuse pink- and red-hued fruit tend to litter the surroundings.

An aerial view of Empress Place. David Marshall used to make his fiery lunchtime speeches under the shade of “the old apple tree” at Empress Place. The two-storey building with three arched doorways was the Marine Police Station that was demolished in the early 70s. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

An aerial view of Empress Place. David Marshall used to make his fiery lunchtime speeches under the shade of “the old apple tree” at Empress Place. The two-storey building with three arched doorways was the Marine Police Station that was demolished in the early 70s. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A more probable candidate is Syzygium grande or the jambu ayer laut, also known as the sea apple. This large native tree grows by the coast and has long been planted as a wayside tree for shade and as a firebreak.25 Many of these trees still stand in the Civic District and in housing estates, where their pompom-like blooms provide nectar26 for sunbirds, flowerpeckers and butterflies, and eventually wither away to yield spherical green fruits that resemble apples.

A Straits Times hack (the broadsheet was no friend of Marshall’s) cynically wrote shortly after Marshall’s victory in 1955 that “there is a suggestion afoot that the Friends of Singapore should add the tree in Empress Place to the list of historical sites and monuments to which plaques are to be affixed, setting out the reasons why the spots deserve well in the memories of the citizens of Singapore”. The reporter then recommended that the tree be renamed Marshalliana saman or Enterolobium marshallense (Enterolobium saman being the scientific name of the rain tree), with the qualifier that he was no botanist and the tree “might not be enterolobium at all”. The tree was certainly claimed as a landmark during Marshall’s tenure as Chief Minister, with The Straits Times including it as part of an imagined tourist itinerary for Singapore in 1956.27

Years later, in 1971, long after Marshall’s retirement from politics, his former corner at Empress Place had become half-forgotten and the haunt of itinerant medicine men peddling sexual aids and pornographic images. These shifty salesmen were said to occupy a “shady sidewalk opposite the Immigration Department”, which was located at the Empress Place building from 1960 until 1986.28

No tree was mentioned in the 1971 article, but in 1980, another journalist, T. F. Hwang, wrote that Marshall’s tree was still standing in front of the Immigration Office at Empress Place. Hwang also laid claim to the phrase “the old apple tree”, which he coined after an old song29 while reporting on a Marshall rally during his rookie days in 1955. The phrase soon gained traction and suggested that Marshall’s tree was no Malus but rather a moniker born of a reporter’s whim.

Hwang’s columns offer no indication of the tree’s true taxonomy, although he juxtaposed Marshall’s tree with another in the area, “nearest to Cavenagh Bridge”, which he identified as a bo or pipal tree (Ficus religiosa). This member of the fig family is usually found in the grounds of Buddhist and Hindu temples, but birds often disperse its seeds on wayside trees. The young bo tree then sends down roots that eventually reach the ground, thicken and envelop its host tree.

Curiously, another observer, F. D. Ommanney, a fisheries scientist who worked in Singapore in the mid-1950s, identified the bo, which he called “peepul”, as Marshall’s tree. He wrote of the Chief Minister:

“He saw [colonialism as] government by foreign bosses for foreign bosses, and saw it all the more clearly for being a foreigner himself. To this effect he thundered daily under the peepul tree, which the press called ‘the old apple’ tree… Mr Marshall as Chief Minister believed in the ‘personal touch’ and in bringing the Government to the People. To this end he held court once a week under the peepul tree, and the masses brought their individual problems and grievances to him.”30

Marshall’s own account of how he began to speak under the tree is told in John Drysdale’s book Singapore: Struggle for Success:

“In order to wake them up, I decided I would go under that tree which was then outside the Finance office, now Immigration. I called it the Old Apple Tree. It was a very tall tree, a Tembusu. There used to be a coffee store there and I asked my friend E. Z. E. Nathan to lend me his little van with a loudspeaker and I stood there at lunchtime because the clerks were there eating. I had a wonderful time. I made it loud enough so that it could be heard at the Cricket Club, the temple of British capitalism. I kept blasting away at British capitalism and British imperialism.”31

A photograph from March 195632 shows Marshall addressing a crowd under his “apple tree”, with his back to the distinctive arched façade of the former Marine Police Station and the Singapore Cricket Club building visible in the far background. Photographs from the 1960s33 show a clump of trees34 at the spot where Marshall would have stood. It is not inconceivable that this grove might have included a bo tree. The lack of detail in the 1956 image, however, makes it impossible to identify the exact tree species, but a botanist consulted for this article said it could be a Syzygium. Marshall’s reference to the tree as a tembusu (Fagraea fragrans) is likely an error; the tree in the photograph has leaves that are markedly larger than those of the tembusu and the trunk lacks the latter’s characteristic vertical fissures.35|

The “apple tree”, which had also been variously described as “in front of the Marine Police Station”,36 (demolished in 1973 to make way for the Empress Place Food Centre37) or “on the spot where Raffles was supposed to have landed”,38 is long gone according to Soh Beow Koon, a retired caretaker of the former Parliament House who worked there from 1954–2002. Soh, in an interview with the author of this article in October 2015, recalled that the tree stood by Empress Place close to the river.

At some point in the 1980s, Marshall’s tree must have perished from natural causes or made way for urban renewal. It was not unheard of for trees in the vicinity to fall victim to disease or changing tastes: five angsana (Pterocarpus indicus) trees that once stood alongside the Old Parliament House were replaced by palm trees in the late 1970s, while another quintet of angsanas that gave Esplanade Park the nickname gor zhang chiu kar (Hokkien for “under the shade of five trees”) succumbed to disease in the 1990s.39 Today, the grounds of Empress Place contain neither Syzygium (rose or sea apple) nor bo trees. There is, however, a straggling Malayan banyan fig growing out of a sliver of soil between the white polymarble statue at the Raffles’ Landing Site and the restaurants of the Asian Civilisations Museum.

The Malay rose apple (Syzygium malaccense) is native to Southeast Asia. Known to locals as jambu bol or jambu merah, the tree was commonly grown for its edible fruits. This is one of the paintings that William Farquhar commissioned Chinese artists to do between 1803 and 1818 when he was Resident and Commandant of Malacca. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

The Malay rose apple (Syzygium malaccense) is native to Southeast Asia. Known to locals as jambu bol or jambu merah, the tree was commonly grown for its edible fruits. This is one of the paintings that William Farquhar commissioned Chinese artists to do between 1803 and 1818 when he was Resident and Commandant of Malacca. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

As for Marshall’s “old apple tree”, it would have been rather fitting if it was indeed a bo tree. On 25 July 1955, during his constitutional standoff with the Governor, the Chinese daily Chung Shing Jit Poh referred to Marshall as a “living Buddha” and hailed his efforts to help ordinary folk. As Chief Minister, Marshall had introduced a Labour Ordinance that improved working conditions and reduced weekly hours to a maximum of 44; he also tabled a Citizenship Bill to naturalise long-time residents and pushed for the replacement of expatriate civil service officers with local staff.40

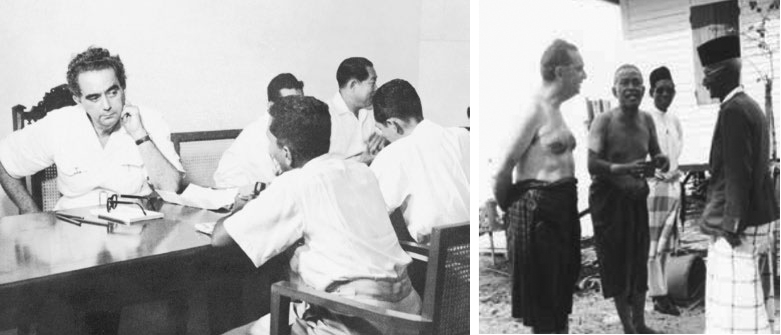

Marshall’s political legacy also included weekly meet-the-people sessions – the first was held on 18 April 1955 – during which he sat with sundry members of the public in a conference room at the Assembly House to hear their woes and help them as best as he could.41 Such tête-à-têtes have since become a mainstay of grassroots politics in Singapore. To be compared with the Buddha, who gained enlightenment under the shade of a bo tree, is truly a befitting testimony to a leader who valued honour over power and sacrifice above self.

(Left) David Marshall at one of his weekly meet-the-people sessions at the Assembly House, the first of which was held on 18 April 1955. David Marshall Collection, courtesy of ISEAS Library, ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore.

(Left) David Marshall at one of his weekly meet-the-people sessions at the Assembly House, the first of which was held on 18 April 1955. David Marshall Collection, courtesy of ISEAS Library, ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore.

(Right) David Marshall meeting Malay villagers in a kampong. David Marshall Collection, courtesy of ISEAS Library, ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore.

Marcus Ng is a freelance writer, editor and curator interested in biodiversity, ethnobiology and the intersection between natural and human histories. His work includes the book Habitats in Harmony: The Story of Semakau Landfill (2009 and 2012), and two exhibitions at the National Museum of Singapore: “Balik Pulau: Stories from Singapore’s Islands” and “Danger and Desire”.

Marcus Ng is a freelance writer, editor and curator interested in biodiversity, ethnobiology and the intersection between natural and human histories. His work includes the book Habitats in Harmony: The Story of Semakau Landfill (2009 and 2012), and two exhibitions at the National Museum of Singapore: “Balik Pulau: Stories from Singapore’s Islands” and “Danger and Desire”.

NOTES

-

Tan, L. (Interviewer). (1984, September 24). Oral history interview with David Saul Marshall [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 000156/28/02, p. 12]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Yeo, K.W. (1972, January). A study of two early elections in Singapore. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 45 (1) (221), 57-80, p. 61. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

National Library Board. (2009). Rendel Commission written by Ng, Tze Lin Tania. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. ↩

-

Yeo, Jan 1972, p. 64. ↩

-

National Library Board. (2010). Sir John Fearns Nicoll written by Chua, Alvin. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. ↩

-

Tan, K.Y.L. (2008). Marshall of Singapore: A biography (p. 250). Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. (Call no.: RSING 959.5705092 TAN) ↩

-

Marshall will come from the under stairs to his big new office soon. (1955, May 4). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore. Legislative Assembly. (1955, August 5). Special report of the House Committee – Accommodation in Assembly House. Singapore Legislative Assembly. Sessional Paper No. L.A. 7 of 1955. Retrieved from Parliament of Singapore website. ↩

-

Choy, S. (1971, July 20). The last governor. The New Nation, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Labour wins – Marshall will be chief minister. (1955, April 3). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Marshall likes sarongs too. (1955, April 23). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

A little snack: Whole sheep. (1955, July 22). The Straits Times, p. 7; Gora and the sheep – another attempt. (1955, October 6). The Straits Times, p. 11; ‘How can I eat when you kick me around like a football?’ (1955, July 26). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Abisheganaden, F. (1956, March 10). 7-day Merdeka Drive. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Mr. David Marshall nailing a poster on a tree at Empress Place, before 1957 [Image of Photograph], [Online]. In D. Marshall. (1971), Singapore’s struggle for nationhood, 1945–59 (p. 45). Singapore: University Education Press. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.57024 MAR) ↩

-

Doubts will not be removed by nailing slogans on trees. (1956, March 14). The Straits Times, p. 6; Mr. M’s posters stolen. (1956, March 14). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lim told: Take the helm. (1956, June 8). The Straits Times, p. 1; The talks fail. (1956, May 16). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

National Library Board. (2016). Lim Yew Hock written by Mukunthan, Michael. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. ↩

-

Abisheganaden, F. (1957, May 1). Marshall: Final act. The Straits Times, p. 1; Majid has to run from rain. (1957, May 28). The Straits Times, p. 7; Police bar Majid from that tree. (1957, May 29). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

PAP told: No ‘apple tree’ rally. (1959, April 15). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

There is no putting the clock back in Singapore. (1959, May 11). The Straits Times, p. 6; The united front. (1957, February 26). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Wild Singapore. (2008, November 10). Jambu bol. Retrieved from Wild Singapore website; Keng, H. (1990). The concise flora of Singapore: Gymnosperms and dicotyledons (p. 78). Singapore: Singapore University Press, National University of Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 581.95957 KEN) ↩

-

National Parks Board. (2014, December 30). Sea apple. Retrieved from National Parks Board website. ↩

-

Wee, Y.C. (2012, October). Plant-bird relationship: Myrtaceae. Retrieved from Bird Ecology Study Group website. ↩

-

Cynicus. (1955, April 9). As I was saying… . The Straits Times, p. 6; Lim, C. P. (1956, July 15). Those tourists! Is this how the future lies? The Straits Times, p. 15. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Wee, S. (1971, December 20). Sales gimmick leaves much to be desire. New Nation, p. 16; Immigration office. (1960, July 11). The Singapore Free Press, p. 4; Wong, J. (1987, December 8). Finds at Empress Place point to colourful past. The Straits Times, p. 16. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

T. F. Hwang takes you down memory lane. (1980, May 24). The Straits Times, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; The song Hwang thought of may have been from Swing Your Lady, a musical comedy released in 1938. A recording of “The Old Apple Tree” from the film can be viewed on YouTube. ↩

-

Ommanney, F.D. (1962). Eastern windows (p. 238). London: Longmans. (Call no.: RDLKL 915.957 OMM) ↩

-

Drysdale, J.G.S. (1984). Singapore, struggle for success (p. 37). Singapore: Times Books International. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 DRY) ↩

-

Singapore Press Holdings (SPH). (1956, March 23). Chief Minister David Marshall speaking to crowd of supporters at Empress Place [Image of Photograph], [Online]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Ministry of Information and the Arts (MITA). (1965, November 2). Singapore River – Boat Quay and Marine Police Station on the right [Image of Photograph], [Online]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Chiang, K.C. (1960). Aerial view of Empress Place and Padang, with the clock tower of Victoria Memorial Hall and part of Cavenagh Bridge (bottom) visible [Image of Photograph], [Online]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Teo Siyang, personal communication. ↩

-

Arsenic and old lace – Marshall has another go at Tan. (1955, March 11). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Food centre to be opened soon. (1973, August 23). New Nation, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Television Corporation of Singapore (TCS). (1956, March 21). Chief Minister David Marshall under the apple tree [Sound Recording]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Boh, S., & Look, W.W. (2015, May 7). Mature rain trees moved to Victoria Theatre and Concert Hall. The Straits Times. Retrieved from Factiva via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Thum, P. (2011, July). Living Buddha: Chinese perspectives on David Marshall and his government, 1955–1956. Indonesia and the Malay World, 39 (114), 256. (Call no.: RSEA 959.8 IMW) ↩

-

Grumble grumble – All day. (1955, April 19). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Thum, Jul 2011, p. 264. ↩