The Padang: Centrepiece of Colonial Design

This expanse of green fringed by grand colonial edifices in the city centre is a statement of British might, as Lai Chee Kien tells us.

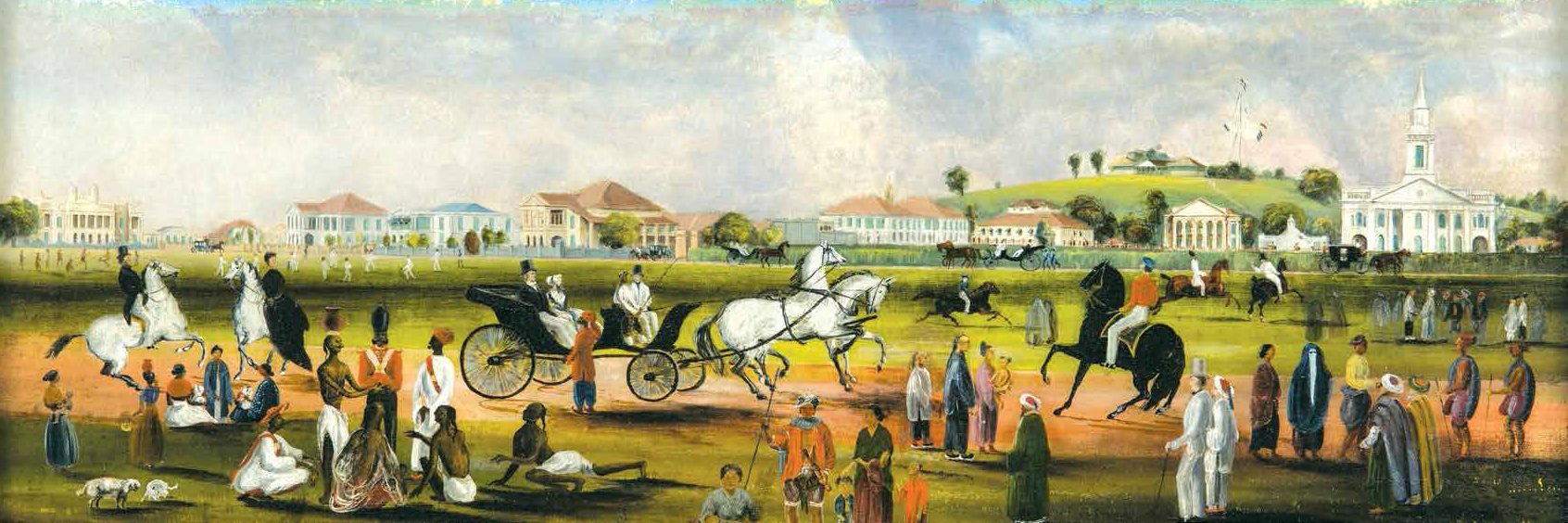

An 1851 oil painting by John Turnbull Thomson, Government Surveyor of the Straits Settlements (1841–53). It shows a view of the Padang from Scandal Point, a small knoll above the shoreline which originally came up to the edge of the Padang. Gift of Dr John Hall-Jones. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

An 1851 oil painting by John Turnbull Thomson, Government Surveyor of the Straits Settlements (1841–53). It shows a view of the Padang from Scandal Point, a small knoll above the shoreline which originally came up to the edge of the Padang. Gift of Dr John Hall-Jones. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.One of the more enduring legacies of the colonial era in Southeast Asia is the spatial design and metropolitan planning that Western powers left behind in the cities they occupied. Spatial design principles that developed in European cities were superimposed onto the landscapes of colonised Southeast Asian cities, replacing the indigenous land and water forms that existed for centuries. In Singapore, the Padang – the expanse of green opposite the National Gallery Singapore and bookended by the Singapore Cricket Club and the Singapore Recreation Club – is one such example.

The Padang in Singapore

The British occupiers of Singapore, led by Stamford Raffles, altered the coastal landscapes of the island soon after their arrival in 1819. Recognising the defensive advantages of a hill overlooking the colonial settlement and anchorage areas, Raffles commissioned a hilltop fort for military surveillance over the settlement plains.1

In 1823, Lieutenant Philip Jackson, whom Raffles had appointed as Surveyor of Public Lands, drew a new urban plan for the town under his direction. The Raffles Town Plan (or Jackson Plan as it was also known) – taking heed of the precedent set by the British in colonial Calcutta − showed a contiguous strip of artificial landscape extending from the sea shore to the closest inland hill, which comprised an open, manicured square protected by a battery wall and Fort Fullerton, with a botanical and experimental gardens in between, and Bukit Larangan or “Forbidden Hill” (subsequently renamed by Raffles as Government Hill).

The three man-made landscape elements designed by the British conspicuously displayed to its indigenous settlers how nature could be manipulated to form a flattened field (the Padang), a garden setting where trees and shrubs were regimented, and defensive structures arranged strategically on a hill.2 The construction of structures on this strip of artificial landscape was deliberate: a church, a court house and government offices between the square and gardens, and Raffles’ own residence on the hill.

In time, the enlarged rectilinear Esplanade − from the Latin word explānāre, meaning “to make level” − became the first semblance of a landscape interface between British colonials and native residents in Singapore. When the Esplanade (which was how the British referred to the Padang back then) was not used for military assemblies, drills and ceremonies, it served as a pitch for cricket, football and rugby matches.

Through military, recreational and ceremonial uses, the Esplanade instilled and socialised concepts of colonial discipline and abidance among the British settlers. The space became a platform that displayed different sides of the British colonial officers: regimental and belligerent on occasion, but at other times, given to rest and recreation.

Edifices of Power Around the Padang

Around the Esplanade, or Padang, the construction of buildings along its edges further stamped colonial legitimacy and emphasised the class divide between the British and the local peoples. As in Prince of Wales Island (later renamed Penang), which the British had earlier colonised in 1786, the British East India Company worked closely with European traders to promote commerce.

One of the concessions the first British Resident in Singapore, William Farquhar, granted to traders was permission to occupy prime land along the fringes of the Padang − as in case of the Bousteads who built their family home there and the Sarkies brothers who leased the building that became the Raffles Hotel.3

These buildings went against Raffles’ instructions that the northern banks of the Singapore River should be reserved strictly for government use. Together with John Crawfurd, the second Resident of Singapore, Raffles moderated Farquhar’s generosity and began to lease land instead to the traders. On this basis, the houses of colonial merchants such as Robert Scott, James Scott Clark, Edward Boustead and William Montgomerie located around the Padang were to serve as temporary residences and hotels until the Town Hall, the Supreme Court and the Municipal Building (later City Hall) were eventually built to establish the government seat of power.4

The process of creating a visually consistent neoclassical facade around the Padang’s edges was thus a gradual process that took place over a century rather than a swiftly executed plan. The construction timeline began with the Parliament House (1826–27) − originally planned as a private home for the Scottish merchant John Argyle Maxwell; St Andrew’s Cathedral – first as a church (1835–36) then a cathedral (1856–61); Victoria Theatre and Concert Hall – first as the Town Hall (1855–62) and then Victoria Memorial Hall (1902–09); the Cricket Club (1860s); City Hall5 – originally the Municipal Building (1926–29); and lastly the Supreme Court (1937–39).

In between all these constructions, on Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee Day on 27 June 1887, an 8-foot bronze statue of Stamford Raffles was unveiled at the Padang, facing the direction of the sea.6 This was an acknowledgement of the contributions of Singapore’s founder and served to further reinforce the might of the British Empire – the statue depicting Raffles with his arms folded in quiet assurance, as if surveying the physical manifestations of his legacy. Ironically, the statue was often struck by stray footballs kicked by overeager players when matches were held at the Padang, and the authorities decided to move it in 1919 to a more dignified site closer to Victoria Memorial Hall.

The statue of Sir Stamford Raffles, facing the sea, was unveiled at the Padang on Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee Day on 27 June 1887. In the background is St Andrew’s Cathedral. Courtesy of Lai Chee Kien.

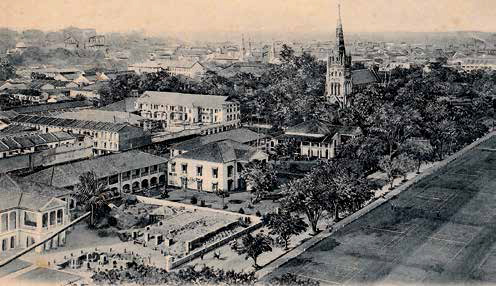

The statue of Sir Stamford Raffles, facing the sea, was unveiled at the Padang on Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee Day on 27 June 1887. In the background is St Andrew’s Cathedral. Courtesy of Lai Chee Kien.Although the Supreme Court was the last building to be built on the Padang’s edge, its history predates all of the other grand structures around the field − dating back to 1823 when the English merchant Edward Boustead was given land to build his family home. The palatial house was subsequently turned into a series of hotels before it was demolished to build the Grand Hotel de l’Europe in 1905 which, together with the Raffles Hotel, was regarded as one of the finest lodgings in Southeast Asia. The hotel closed down in 1932 and the site was acquired by the government to build the Supreme Court.

A view of the Grand Hotel de l’Europe (left) being built (later demolished to build the Supreme Court), several residential houses belonging to European merchants, lawn tennis courts on the edge of the Padang and St Andrew’s Cathedral (on the right). Likely photographed in the early 1900s. Courtesy of Lai Chee Kien.

A view of the Grand Hotel de l’Europe (left) being built (later demolished to build the Supreme Court), several residential houses belonging to European merchants, lawn tennis courts on the edge of the Padang and St Andrew’s Cathedral (on the right). Likely photographed in the early 1900s. Courtesy of Lai Chee Kien.The last Padang-facing structure to be constructed, the neoclassical Supreme Court, was erected at a time when the transatlantic art deco and modernist movements in architecture had already begun to influence architectural design all over Southeast Asia. Upon its completion in 1939, the green expanse of the Padang with its grand edifices of architecture on its edges evoked the colonial vision of power and discipline.

The periphery of the Padang where it met the sea, meanwhile, had become a colonial tree-lined promenade for the public. As a visitor in the 1850s remarked of the Esplanade: “The scene is enlivened twice during the week by the regimental band, on which occasions the old women gather together to talk scandal, and their daughters to indulge in a little innocent flirtation.”7

The commemorative aspect of Esplanade Park, as it was known by then, was further enhanced with the construction of the Cenotaph war memorial in 1922, and when Tan Kim Seng Fountain was moved there in 1925. After World War II, a war memorial dedicated to the hero Lim Bo Seng was erected at Esplanade Park. From 1953 onwards, Esplanade Park was renamed Queen Elizabeth Walk and became an important seafront promenade in the city.

From Public Square to Padang

The concept and use of an open space such as the Padang was tested elsewhere in the British Empire before its construction in Singapore. As the historian Robert Home has theorised, the public square was one of eight components of the “Grande Model” of British colonial settlement since the 17th century.8 The geometric grid layout and the incorporation of an open square represented “the ultimate symbol of the imposition of human order on the wilderness.” The extent of physical manipulation was apparent in places as diverse as colonial Savannah and Charleston in the US and Adelaide in Australia, where the creation of towns in the middle of plantations altered land, flora, fauna and human life irrevocably.

Singapore’s Padang took inspiration from a type of urban field known as maidan, which was also found in places such as India and Penang. The term maidan has Persian roots, and was widely used in Islamic cities as early as the 9th century to connote the setting of a formal rectilinear open space. In Persia, the maidan was conceived as part of the royal conurbation within the city.

The ruler who best articulated the concept of the maidan in designing urban space was Shah Abbas I of Isfahan (in modern-day Iran). During his reign, the nucleus of Isfahan was relocated to a new maidan measuring 440 yards long and 160 yards wide and named Maidan-i Naqsh-i Jahan. Built between 1597 and 1602, this maidan became the new centre of the first Shi’ite dynasty in Iran. According to Stephen Blake, spatially, the organised functions of state power, religion, commerce, education, recreation and commemoration were clearly expressed along the four margins of this space, and it became a new model in its time.9

The concept of the Padang originated in Persia, where it was known as the maidan, a formal rectilinear open space in the city centre. During the reign of Shah Abbas I of Isfahan (in modern-day Iran), the nucleus of the city was relocated to a new maidan called Maidan-i Naqsh-i Jahan. Built between 1597 and 1602, this maidan became the new centre of the first Shi’ite dynasty in Iran. J. P. Richard / Shutterstock.com

The concept of the Padang originated in Persia, where it was known as the maidan, a formal rectilinear open space in the city centre. During the reign of Shah Abbas I of Isfahan (in modern-day Iran), the nucleus of the city was relocated to a new maidan called Maidan-i Naqsh-i Jahan. Built between 1597 and 1602, this maidan became the new centre of the first Shi’ite dynasty in Iran. J. P. Richard / Shutterstock.comA wide canal ran along the edges of Maidan-i Naqsh-i Jahan. Trees were planted between the canal and the perimeter – a 20-foot-wide grassy space that shaded shops as well as a dozen major gates and openings into the square. Outside this perimeter, the palace grounds, the bazaar, mosques, gardens, madrasahs and other public and commemorative architectural elements collectively articulated the shah’s role as the purveyor of political might as well as economic and civic life. As Blake has described, the maidan was the site for the enactment of daily and seasonal imperial spectacles: polo, horse-racing, military parades, fireworks displays, mock battles, receptions of ambassadors, courtly audiences and religious festivals.

The idea of the maidan as a type of artificial lawn in India may have been transplanted from cities in the Middle East and pre-existed well before the arrival of the British.10 After British troops recaptured Calcutta in 1757, Fort William at the centre of the maidan was re-secured, and residential homes and other structures around it were demolished and cleared to form an esplanade.11 The British constructed important public buildings near the edges of the maidan as visible signs of English order and progress in colonial Calcutta.

The Calcutta maidan combined various features of the Persian model with a British innovation: a walled fort constructed adjacent to or within the maidan. The same maidan model with a defensive fort was adopted in other Indian cities such as Bombay and Madras that the British also colonised. As Britain expanded its sphere of influence in the region, Burma, Malaya and Singapore were later established as English colonies to curtail French interest in Indochina and Dutch hegemony in the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia).

The port cities of Penang, Malacca and Singapore (collectively known as the Straits Settlements) in the Malay Peninsula became part of this British colonial network. On the Malay Peninsula, the defensive form was first created in Penang after it was annexed by the British in 1786. The Padang was constructed alongside Fort Cornwallis at a strategic cape location with the Penang Cricket Club and government buildings at the other end.12 The arrangement would be replicated in Singapore with the establishment of Fort Fullerton along Battery Road, until Government Hill was deemed to be a more strategic area and Fort Canning was constructed here in 1861.

The Padang in Post-Colonial Singapore

According to Ananda Rajah , the introduction of the annual National Day Parade in Singapore after Independence in 1965 is symbolic of the country’s arrival as an imagined national and political community.13 Over the last 50 years, three locations have hosted the annual National Day Parade: the Padang, the National Stadium and Marina Bay.

The stadium and the Padang each hosted the parade 18 times until 2007 when it was moved to the Float@Marina Bay with its floating platform and open-air stage. The Padang was again the venue for the parade in 2010 and 2015, while Marina Bay hosted the parade seven times before it returned to the new National Stadium in 2016.

Interestingly, there are implications for the various sites that have taken turns to host the parade. For instance, the decision to hold the newly independent nation’s first National Day Parade at the Padang in 1966 can be seen as a subversion of colonial rule, appropriating a symbolically potent site that had represented British authority in Singapore for over a century.

The construction of the National Stadium in 1973 created an alternative congregation space for national spectatorship.14 The key feature of the National Stadium is a manicured flat green field, much like the Padang, but with people, instead of buildings, filling the spaces of its periphery.

The staging of the National Day Parade at Marina Bay is of interest because the site is spatially analogous to that of the Padang. The layout and the constitutive elements are similar, although visually, Marina Bay is very different from the Padang, having been reclaimed from the sea, and creating Marina Reservoir in the process.

Looking at the four edges of the rectilinear reservoir, one can see that the old buildings along its historic edge near the Padang have been refitted and given new functions. Reminiscent of the maidan in Isfahan, the remaining three edges have been taken up by structures devoted to commerce (Marina Bay Financial Centre); recreation (Marina Bay Sands casino resort); and leafy gardens (Gardens by the Bay).

Seen as a whole, Marina Bay is a rectangular, flat piece of water surface that has been artificially constructed, with its edges flanked by mostly new buildings that are key to Singapore’s next phase of development as a global city. Spatially, it is a “liquid padang”, serving similar functions but providing a view towards the city’s future, especially since the colonial Padang and its period buildings have been mostly emptied of their original functions – most recently the amalgamation of City Hall and the Supreme Court into the National Gallery Singapore. Collectively, the old and the new “padang” evoke the giant leaps of time and progress that Singapore has made since Raffles first envisioned his town plan in 1822.

Dr Lai Chee Kien is an Adjunct Associate Professor at the Singapore University of Technology and Design, and a registered architect. His research interest lies in the history of art, architecture, settlements, urban planning and landscapes in Southeast Asia.

Dr Lai Chee Kien is an Adjunct Associate Professor at the Singapore University of Technology and Design, and a registered architect. His research interest lies in the history of art, architecture, settlements, urban planning and landscapes in Southeast Asia.

Notes

-

Letter from Stamford Raffles to William Farquhar dated 6 February 1819, as cited in L. T. Firbank, A History of Fort Canning (no records), p. 16. ↩

-

Lai, C, K. (2006, July). Botanical imaginations of Southeast Asia in the 19th and 20th centuries. Singapore Architect, (233), pp. 70–79. Call no.: RSING 720.5 SA ↩

-

A new hotel in Singapore. (1887, September 21). Straits Times Weekly Issue, p. 4; Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Liu, G. (2006). Raffles Hotel (pp. 17–18). Singapore: Editions Didier Millet. Call no.: RSING q915.9570613 LIU ↩

-

Lee, K. L. (1988). The Singapore House 1819–1942 (pp. 148–149). G. Liu. (Ed.). Singapore: Times Editions. Call no.: RSING 728.095957 LEE ↩

-

The former City Hall and Supreme Court buildings, both gazetted national monuments, were renovated and opened in November 2015 as the National Gallery Singapore housing the largest public collection of modern art in Singapore and Southeast Asia. ↩

-

The statue of Stamford Raffles was commissioned by then Governor of the Straits Settlements Frederick Weld for Singapore in 1887, and designed and sculpted by Thomas Woolner. It was later transferred to its present location at the Victoria Memorial Hall. See Woolner, A. (1917). Thomas Woolner, R.A., sculptor and poet: His life in letters (p. 326). New York: E. P. Dutton & Company. Retrieved from Internet Archive. ↩

-

Jayapal, M. (1992). Old Singapore (p. 25). Singapore: Oxford University Press. Call no.: RSING 959.57 JAY-[HIS] ↩

-

Home, R. K. (1996). Of Planting and planning: The making of British colonial cities. (pp. 8–23). London: E. & F. N. Spon. Call no.: RART 711.409171241 HOM ↩

-

Blake, S. P. (1999). Half the world: The social architecture of Safavid Isfahan, 1590–1722 (pp. xvi–xvii). Costa Mesa: California: Mazda. Call no.: RART q720.95595 BLA ↩

-

Anuradha Mathur, A. (1999). Neither wilderness nor home: The Indian maidan. In J. Corner. (Ed.), Recovering landscape: Essays in contemporary landscape architecture (pp. 206–208). Sparks: Princeton Architectural Press. Call no.: RART 712 REC ↩

-

Chattopadhyay, S. (2005). Representing Calcutta: Modernity, nationalism, and the colonial uncanny (p. 46). New York: Routledge. Call no.: R 954.147 CHA ↩

-

Garnier, K. (1923, April). Early days in Penang. Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1 (1 (87)), 5–12., pp. 5–6. Call no.: RCLOS 959.5 JMBRAS. The settlement grew from the cleared ground of the esplanade, a fort and a small bazaar, and within a year attracted families of different ethnicities to settle there, alongside the resident Malay populations. ↩

-

Rajah, A. (1999). Making and managing tradition in Singapore: The National Day Parade. In K.-W. Kwok et al. (Eds.), Our place in time: Exploring heritage and memory in Singapore (pp. 101–109). Singapore: Singapore Heritage Society. Call no.: RSING 959.57 OUR-[HIS] ↩

-

Lai, C.K., et al. (2016). Building memories: People, architecture, independence (pp. 114–116). Singapore: Achates 360 Pte Ltd. Call no.: RSING 720.95957 LAI ↩