Claudius Henry Thomsen: A Pioneer in Malay Printing

Danish missionary Claudius Henry Thomsen produced some of the earliest Malay-language publications in Singapore and the Malay Peninsula. Bonny Tan sheds light on this pioneer printer.

Danish missionary Reverend Claudius Henry Thomsen is credited with producing some of the earliest Malay-language publications in Singapore and the Malay Peninsula. All rights reserved, Milner, A.C. (1980). A Missionary Source For a Biography of Munshi Abdullah. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 53(1 (237)), 111–119.

Danish missionary Reverend Claudius Henry Thomsen is credited with producing some of the earliest Malay-language publications in Singapore and the Malay Peninsula. All rights reserved, Milner, A.C. (1980). A Missionary Source For a Biography of Munshi Abdullah. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 53(1 (237)), 111–119.In the flickering light of the candles, the men relentlessly worked the press. Their bodies slicked with perspiration, and staving off hunger and sleep, they continued tirelessly through the night. As the handpress could not cope with the demands of printing this massive work, Munshi Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir, the learned Malay teacher and translator, had worked non-stop over two days to cast additional Malay font types to complete the job. The item in press was believed to be Stamford Raffles’ Proclamation of 1 January 1823, likely the earliest publication printed in Singapore.1

Munshi Abdullah, with the assistance of a young Eurasian called Michael, printed 50 copies of the work in English and 50 in Malay. It was three in the morning by the time the documents were ready and these were distributed around town as instructed by Raffles. The founder of Singapore had insisted that the settlement’s laws be published by that morning, the first day of the New Year.2

Likely working alongside these men that same night was the Danish missionary, Reverend Claudius Henry Thomsen, who is credited with bringing Singapore’s first press with him when he arrived in the settlement on 19 May 1822. Besides printing Singapore’s earliest known English works, Thomsen would forge the path as a pioneer printer of Malay and Bugis translated works in the Malay Peninsula, long before better known missionary printers of publications in Malay, such as William G. Shellabear and Reverend Benjamin Keasberry, arrived on the scene.

Munshi Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir was an accomplished Malay scholar and the “father of modern Malay literature”. He helped guide Claudius Henry Thomsen in his understanding of the Malay language. Illustration by Harun Lat. All rights reserved, Hadijah Rahmat. (1999). Antara Dua Kota. Singapore: Regional Training and Publishing Centre.

Munshi Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir was an accomplished Malay scholar and the “father of modern Malay literature”. He helped guide Claudius Henry Thomsen in his understanding of the Malay language. Illustration by Harun Lat. All rights reserved, Hadijah Rahmat. (1999). Antara Dua Kota. Singapore: Regional Training and Publishing Centre.Preparations for the East

Thomsen was originally from Holstein, Lower Saxony,3 and trained at the Gosport Seminary in England in 1811 where he mastered the study of classical languages and subjects such as geography and astronomy. Knowing that he was going to be posted to the newly established mission station in Malacca, Thomsen began learning Malay4 and Dutch, with the expectation that Malacca would revert to Dutch rule in time to come.5

Recently married, Thomsen set sail with his wife for the East in April 1815 under the auspices of the London Missionary Society (LMS) – a non-denominational Protestant society founded in 1795 in England – arriving in Malacca five months later on 27 September.

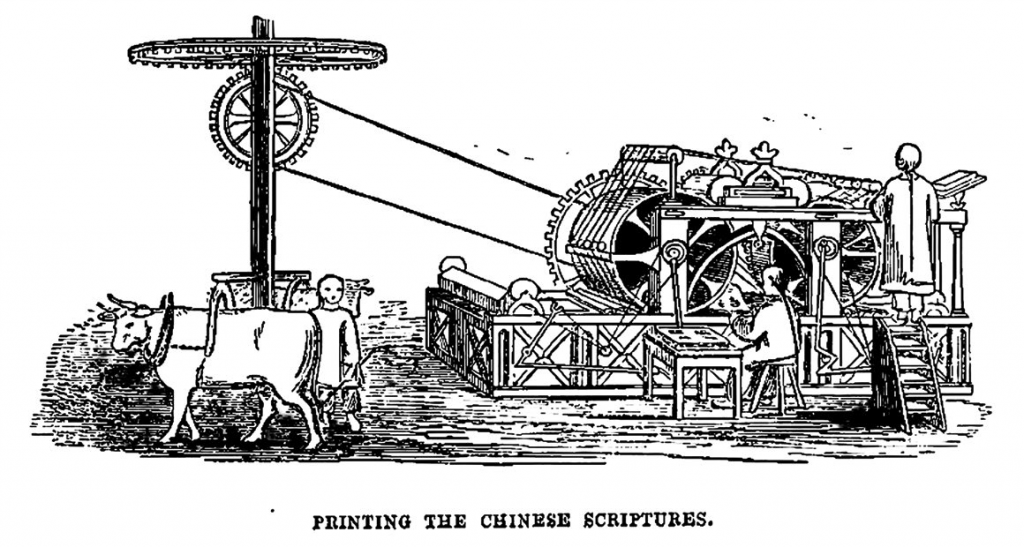

The Chinese missions in Malacca had opened that same year6 with the objective of becoming the LMS base for missionary work in China. At the time, China was closed to foreign trade and was antagonistic towards Christian missionary work. Robert Morrison, a pioneer missionary in China, had earlier sent his colleague William Milne to head the Malacca mission station. Before long, a few schools and a Chinese printing press had been established in Malacca. In formulating his plans for the station in the Malay Archipelago, Morrison envisioned that there be “… that powerful engine, the Press.”7

Upon his arrival in Malacca, Thomsen was introduced to Munshi Abdullah who helped guide him in his understanding of the Malay language. It is through Abdullah’s autobiography, Hikayat Abdullah (Stories of Abdullah), that the earliest picture of Thomsen was formed.8 Thomsen spent his early months in Malacca mastering the language, beginning with the translation of the Gospel of Matthew based on the Batavia-Dutch edition of 1758.

Printing in Malacca

In November 1816, more than a year after Thomsen first set foot in Malacca, the press and font types for English and Arabic text arrived from Serampore, West Bengal, which was then the main type foundry for the region. Six trained printers came along to operate the press, four more workers than requested, thereby inflating the monthly expenditure of the Malacca station.

Upon seeing the press from Serampore, Munshi Abdullah noted: “The Malay letter-types… the likes of these as well as other printing apparatus I have never seen in my life before. When I saw them I was amazed to think how the inventiveness and ingenuity of man have produced machines to do such work.”9

Academic Ibrahim Ismail notes that the new press was used for all Malay publications produced in Malacca “except for title pages with large Jawi letters, which were printed from woodcuts”. The Jawi calligraphy was likely the work of Munshi Abdullah, while the engraving of the title on wood was done by experienced Chinese typecutters from the Chinese printing press in Malacca.10

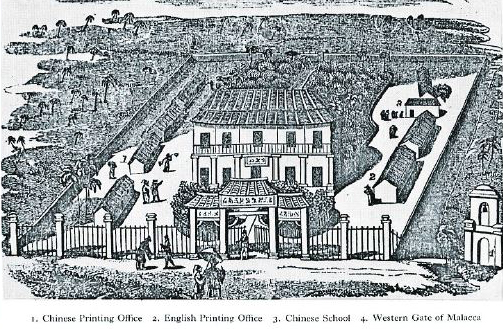

The Chinese and English printing offices in Malacca where Thomsen’s printing press was likely co-located with the English press. Missionary Sketches XXVIII, January, 1825. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The Chinese and English printing offices in Malacca where Thomsen’s printing press was likely co-located with the English press. Missionary Sketches XXVIII, January, 1825. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.Unfortunately, Thomsen did not see the arrival of this press as his wife’s illness led to his sudden departure for England on 12 September 1816. However, he left behind two Malay manuscripts that were ready for printing. In the meantime, Munshi Abdullah was taught by the English Protestant missionary, Walter Henry Medhurst, who arrived in Malacca in June 1817,11 to set the types and operate the printing press.

Thus, the first Malay books in the Malay Peninsula – The Ten Commandments with the Lord’s Prayer appended and Dr Watts’ First Catechism – were published in May 1817 during Thomsen’s absence. The manuscripts were sent to “an excellent Malay scholar”, Major J. McInnis of the 20th Regiment of the Bengal Native Infantry in Penang, for review before being published. Thomsen returned to Malacca on 29 December 1817, sadly bereft of his wife. While he was in England though, Thomsen pursued further training in printing, and returned with files and borers to make new font types, along with old English metal types that he recast into new fonts.12

Thomsen quickly immersed himself in the work of the missions, reopening the Malay school, starting a new school for Malabar Indians, distributing Christian tracts and running a very active printing press. Milne noted Thomsen’s abilities in teaching youths and his natural delight in doing so. Later, Thomsen’s contemporary Samuel Milton, who was also a missionary, would comment that Thomsen had “an excellent talent for composing in the English and Malay language, hymns, short prayers, lessons and other elementary books well adapted to the capacity of children.”13

In fact, one of Thomsen’s earliest publications14 was A Spelling Book (1818), likely used in the schools and one of the earliest Malay textbooks to be printed in the Malay Peninsula. Another first in Malay printing was Bustan Arifin (1821–22), the first Malay magazine published in the Peninsula and targeted at Malay youths. Other publications include An Alphabet, Syllabrium and Praxis in the Malayan Language (1818); A Vocabulary of the English and Malayan Languages (1820) as well as various religious tracts and textbooks.

By 1819, the Malay printing press was under the full charge of Thomsen who employed 12 youths – eight boys and four girls – to work as bookbinders, printers and illustrators.15 The printing press was, however, a much smaller enterprise in terms of size and financial resources compared with the Chinese press. By 1820, Thomsen had married Mary Ann Browne.

Printing in Singapore

The LMS was established in Singapore in October 1819, a few months after the founding of the settlement. Samuel Milton was the first head of the Singapore mission.

Thomsen left Malacca for Singapore on 11 May 1822 and arrived on 19 May, although academic Anthony Haydock Hill (A.H. Hill) suggests that Thomsen and Munshi Abdullah had visited Singapore earlier, likely after June 1819. Thomsen immediately aligned himself with Raffles who commended the former’s proficiency in Malay. Both men agreed to establish a press, with Raffles stating: “I look with great confidence to the influence of a well-conducted press in this part of the East.”16

Between August and October 1822, Milton and Thomsen held discussions to obtain presses for the new settlement. On 8 December 1822, Milton travelled to Calcutta, India, to acquire printing presses and returned only in April the following year. As Raffles did not expect to remain long in Singapore, he instructed Thomsen to begin printing in Milton’s absence, likely between December 1822 and January 1823, and possibly using the handpress that Thomsen had brought with him to Singapore.17

In February 1823, Thomsen proudly reported to the LMS that they were now “printing in English & Malay & have a small type-Foundery & are doing bookbinding. Government has been pleased to honour our little press… with the printing of all public documents both in English & Malay – one of the lads composes in English and one the Malay – one is Pressman – one does type cutting & another bookbinding… ”.18

Some historians have implied this was the same press brought by Medhurst to Penang. Thomas Beighton, the missionary to the Malays in Penang, was new to the Malay language, and was likely unable to make use of the press for the community as efficiently as Thomsen could. Thomsen most probably took the press in 1821 when he visited Penang and brought it to Singapore the following year.19

The press was invented by well-known printer, Peter Perring Thoms of the East India Company, while he was stationed at Macau. Originally used for printing wood blocks, the small press had a board and roller, and cost no more than six Spanish dollars. The press was later modified by Thomsen so that it could operate metal types and work with adapted Malay fonts, allowing it to print at least eight pages, up from the original four.20 It was this modified handpress that was most likely used to print some of Singapore’s earliest publications. It was only after the press had begun operations that Thomsen made a formal request on 17 January 1823 to operate printing presses in Singapore. Approval was given by Raffles on 23 January.21

By mid-1823, there appeared to be two groups running different presses at the same time. The one operated by Milton at his home began printing in June 1823 and served the Singapore Institution. It was much larger compared with the handpress run by Thomsen, who was printing for the LMS. Both presses also printed works for the government.22

Unfortunately, it was unsustainable to run two separate presses and when Milton left the mission in 1825, his printing press was handed over to Thomsen. Thomsen had three large buildings constructed at the junction of North Bridge Road and Bras Basah Road, on land owned by Anglican priest Revered Robert Burn, to house the printing press, its workmen and stores.23

First Publications in Singapore

The title and date of the first publication printed in Singapore cannot be ascertained. Milton mentioned an early attempt at printing a periodical and an exposition of the Book of Genesis in Chinese in a letter to George Burder, treasurer and secretary of the LMS, dated 23 September 1822. He also had plans to print pamphlets and later the New Testament in Siamese. However, no mention is subsequently made of these publications and so it is assumed that they were never completed.24 Academic Leona O’Sullivan holds the view that printing in Singapore began with the publication of Raffles’ Proclamation of 2 December 1822,25 while Dr John Bastin records that it is Raffles’ Proclamation of 1 January 1823.26

The Mission Press under Thomsen published not only government resources, but also various Christian tracts and bibles as well as school textbooks. While in Malacca, Thomsen had instructed Munshi Abdullah to create a Malay word list to which he would supply the English translations. Keen to learn English, Abdullah produced 2,000 words after a month’s work. This wordlist was published as A Vocabulary of the English and Malayan Languages in Malacca in 1820, and it likely became the first published vocabulary in Singapore when reprinted by Thomsen in 1827.27

Thomsen used the publication as a teaching tool at the Malay school in Malacca as well as to help improve his own Malay vocabulary. Additionally, Thomsen used the vocabularly as a framework to expand his knowledge of the Bugis language, with the third edition incorporating Bugis translations of the Malay words. This was one of the last publications Thomsen produced in Singapore but the Malay word-list continued to be published as late as 1860, long after his death.28

A group of Bugis men posing for a photograph below their house built on wooden stilts, c.1890s. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A group of Bugis men posing for a photograph below their house built on wooden stilts, c.1890s. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Besides making initial inroads into Malay publishing, Thomsen stands as a forgotten pioneer of Bugis translated works. His interest in the Bugis language probably arose while he went onboard ships and boats to distribute Christian tracts during the trading season and noticed the influx of Bugis prahu, a small sailing boat used by the Bugis in the Malay Archipelago. Thomsen published his first Bugis tract in 1827 after having recruited a competent transcriber in Buginese for the publication of the material.29 Although the Bugis tracts were not considered good translations and he never quite achieved his dream of translating the Bible into Buginese, his English-Malay-Bugis Vocabulary (1833) and A Code of Bugis Maritime Laws (1832) are some of the earliest works in the Bugis language.

Thomsen’s “crowning achievement”, however, as academic Ibrahim bin Ismail notes, was his translation of the New Testament into Malay based on the Calcutta edition. With the help of the Anglican padre Robert Burn, Thomsen devoted much of his time translating the work between 1830 and 1831. With funding from the British and Foreign Bible Society, he printed 1,500 copies of the publication in June 1831.30

Departure from Singapore

By the end of 1833, Thomsen was near exhaustion and could do nothing else except concentrate on printing. He had been the only missionary in town for some time and spent the past years distributing tracts on a daily basis, besides running the press and managing the school and other services. Missionary Jacob Tomlin described it thus:

“I made several visits with Mr T to the ships, prahus, and junks and gave away several Portuguese Bibles and Testaments… While Mr T was busily engaged in distributing these in the cabin, I was surrounded by a crowd of Chinamen on deck, most of whom could read, and were very grateful for the books… My bundle was soon exhausted, for there were about fifty persons in all.”31

Although weighed down by responsibility, Thomsen remained hospitable and welcoming to overseas visitors, as described by visiting missionary John Evans: “Our arrival being reported, the Rev Mr Thomsen immediately came out in a boat to meet us, and compelled us to leave the ship that night, it being then eight o’clock, and go with him. Mrs Thomsen received us with much pleasure … .”32

Some academics, such as Ching Su, suggest that Thomsen left Singapore in ignominy, having sold off the Mission Press to the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) without the permission of the LMS, and then resigning from the LMS soon after returning home to England.33 In truth, Thomsen had offered to sell the press to the LMS at the Penang station but they were unable to pay a higher price than what the ABCFM could, all parties fully aware that the press was worth much more than the 1,500 Spanish dollars that the ABCFM had offered.34 Thomsen left Singapore on 10 May 1834 on account of his wife’s affliction with cancer. She died soon after their arrival in England in October, and the following month Thomsen resigned from the LMS.35

The ABCFM had ambitious plans for printing in the region, and thus their acquisition of Thomsen’s Mission Press. In their report in the Missionary Register of 1835, the ABCFM outlined the unique position Singapore had as a printing centre:

“… Printing establishments should be placed at the great central points of trade and intercourse, in order that they may become Manufactories of Books and Tracts, and Depots whence they may be issued and carried abroad to the myriads who are waiting to receive them. For such an establishment, Singapore presents peculiar advantages, in respect to climate, security and frequent intercourse with all the ports on that part of the continent and the islands of the Indian Archipelago.”36

Thomsen had set the foundations for a printing press in Singapore, producing works in the local languages at a time when many of his contemporaries had switched their attention to China. His grammar books, vocabulary guides, Bugis-language works and Malay scriptural translations, although not perfect, were reprinted beyond his lifetime and paved the way for similar works to be published under pioneers such as Keasberry, and later, Shellabear. More importantly, the humble printing press stirred in the locals an interest for the printed word, and opened up new vistas for them to explore.

SOME KEY PUBLICATIONS BY CLAUDIUS HENRY THOMSEN

Bustan Arifin: Malay Magazine (1821–22)

This is the first Malay magazine to be published in the Malay Peninsula. A quarterly edition with about 30 pages per issue, it was written for a Malay readership and covers a wide range of subjects such as history, biography, philosophy and religion. It followed the framework set by an earlier periodical – the Indo-Chinese Gleaner. Missionaries Samuel Milton and Thomas Beighton regularly wrote columns for the magazine, the former on astronomy while the latter profiled heroes of history and the Christian faith. It became popular and was even read by the royal families in the Malay Peninsula. However, only six issues were published between January 1821 and April 1822 as Thomsen left for Singapore soon after.37

The Psalter, or Psalms of David, with the Order for Morning and Evening Prayer, Daily Throughout the Year (Puji-pujian iaitu Segala Zabur Daud Terbahagi atas Jalan Seperti yang Dipakai oleh Sidang Perhimpunan dalam Gereja lagipun Beberapa Doa yang Dipakai Sehari-hari Pagi dan Petang) (1824) [Call no.: RCLOS 221 PUJ]

Thomsen was recorded as the translator in this publication printed at the Institution Press in 1824. The homily and prayer book in Malay was used during Sunday services in Singapore, and is a translation of the one commonly used in Anglican church services. A sample of this published translation was given to Raffles who commended Thomsen for the quality of its translation.38

A Vocabulary of the English and Malayan Languages (1827) [Call no.: RCLOS 428.1 VOC (photocopy of an incomplete version)]

The word-list of 2,000 words is one of the earliest collaborative works by Munshi Abdullah and Thomsen, compiled sometime between 1815 and 1816.39 It was first published in Malacca in 1820 to aid visiting foreigners in communicating with the locals and used as a teaching tool by Thomsen at his Malay school. The second edition was published in Singapore in 1827, likely the first vocabulary guide printed in Singapore. It provides insights into how Malay was used in Malacca and Singapore in the early 19th century. The only known complete set is found at the National University of Singapore Library’s Singapore/Malaysia Collection.

The third edition published in Singapore in 1833, entitled A Vocabulary of the English, Bugis, and Malay Languages: Containing About 2000 Words, is one of the last works Thomsen would print in Singapore. The Bugis manuscript had languished for several years until a donation of 30 Spanish dollars was made by a friend of Thomsen’s to defray the printing cost.40 An enlarged and improved edition was printed by Evans in Malacca and Penang in 1837,41 with the profits used to raise 400 Spanish dollars for building a new wing for the Anglo-Chinese College in Malacca. The vocabulary continued to be printed in Singapore as late as 1860.42

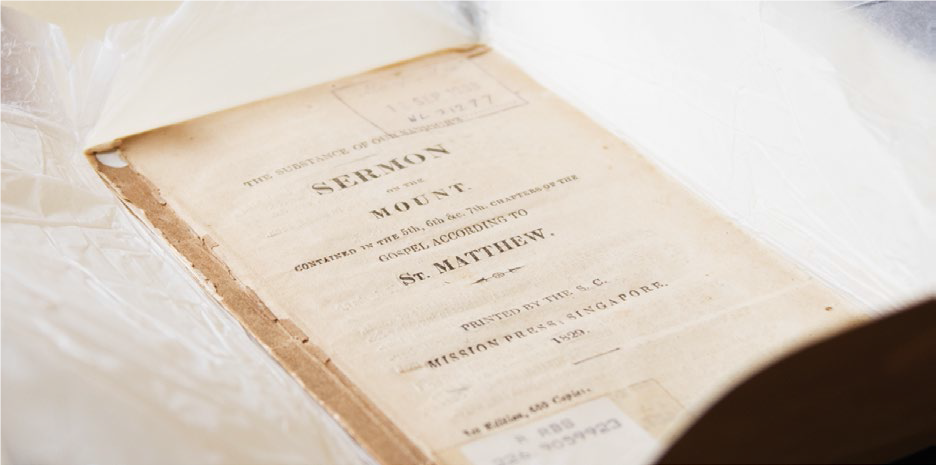

The Substance of our Saviour’s Sermon on the Mount Contained in the 5th, 6th & c. 7th Chapters of the Gospel According to St Matthew (1829) [Call no.: RRARE 226.9059923 SER; Microfilm no.: NL 21277]

This is a Malay translation of Jesus’s core teachings as found in his Sermon on the Mount in the Gospel of Matthew. The booklet begins with a single-page orthography of the Malay language as used in the text and concludes with a non-biblical six-stanza poem on the means to salvation.

Thomsen is believed to be the translator of the booklet and author of the poem, having completed a translation of the Gospel of Matthew in 1821 while in Malacca.43

This booklet is the earliest extant Malay publication printed in Singapore and is found in the National Library, Singapore.

The Sermon on the Mount is the longest and one of the most often quoted teachings of Jesus from the Gospel of Matthew in the Bible. The translation by Claudius Henry Thomsen is one of the earliest extant Malay publications printed in Singapore.

The Sermon on the Mount is the longest and one of the most often quoted teachings of Jesus from the Gospel of Matthew in the Bible. The translation by Claudius Henry Thomsen is one of the earliest extant Malay publications printed in Singapore.

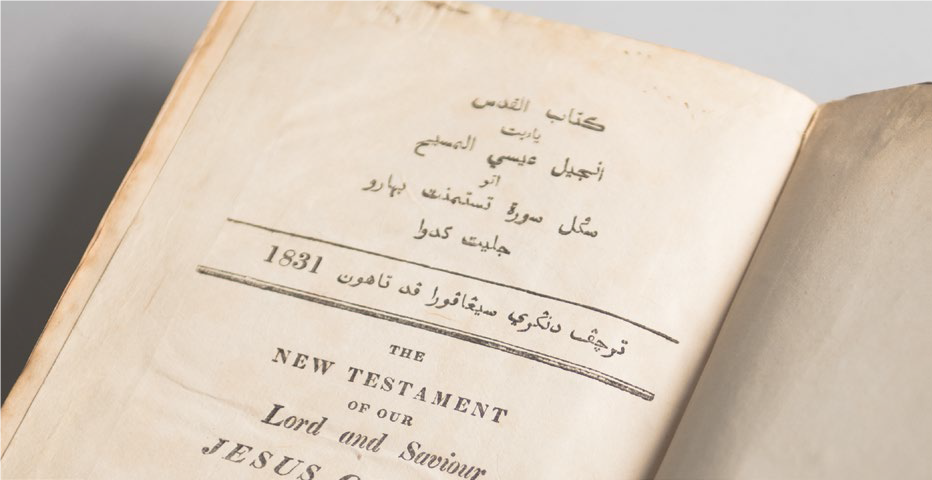

The New Testament of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ in Malay (Kitab Al-Kudus, ia-itu, Injil Isa Al- Masihi atau Segala Surat Testament Bahru) (1831) [Call no.: RRARE 225.59928 BIB; Microfilm no.: NL 27664, NL 9717]

Thomsen began work on translating the New Testament of the Bible into Malay when he realised that the stocks of his Calcutta edition was running low. He devoted 12 to 15 months of fulltime work to carry out the translation, and finally printed 1,500 copies in June 1831, noting that this event “will form an era in the Malay Mission”. The British and Foreign Bible Society contributed 800 sicca Rupees for its publication.44 The National Library, Singapore, has the first edition of this rare publication.

The National Library’s copy of The New Testament of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ in Malay. Thomsen spent 12 to 15 months translating the New Testament into Malay, and printed 1,500 copies in June 1831.

The National Library’s copy of The New Testament of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ in Malay. Thomsen spent 12 to 15 months translating the New Testament into Malay, and printed 1,500 copies in June 1831.

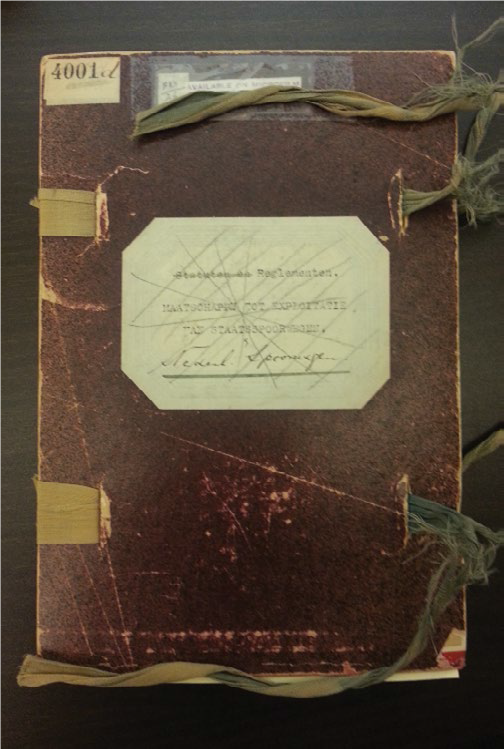

A Code of Bugis Maritime Laws (1832) [Call no.: RRARE 343.5984096 COD; Microfilm no.: NL 6400]

The National Library, Singapore, has a copy of this publication edited by Thomsen and published in 1832. It contains the Bugis maritime laws in the Bugis script with English translations as well as an appendix of vocabulary terms. Although Thomsen’s translation was criticised as not being accurate, the publication was well received as far away as Bengal and was subsequently translated and published in French in 1845, German in 1854 and Dutch in 1856.45

The National Library holds a copy of A Code of Bugis Maritime Laws, which was edited by Thomsen and published in 1832. The publication was subsequently translated into French, German and Dutch.

The National Library holds a copy of A Code of Bugis Maritime Laws, which was edited by Thomsen and published in 1832. The publication was subsequently translated into French, German and Dutch.

The author wishes to thank Dr John Bastin and Reverend Malcolm Tan for reviewing this article and sharing their valuable insights.

Bonny Tan is a former Senior Librarian at the National Library, Singapore. She currently resides in Vietnam with her family and is a regular contributor to BiblioAsia magazine.

Bonny Tan is a former Senior Librarian at the National Library, Singapore. She currently resides in Vietnam with her family and is a regular contributor to BiblioAsia magazine.Notes

-

Bastin, J. (1981). The letters of Sir Stamford Raffles to Nathaniel Wallich 1819–1824. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 54 (2 (240)), 1–73, pp. 52–53. Call no.: RCLOS 959.5 JMBRAS. Bastin notes that Regulation No. 1 – “A Regulation for the Registry of Land at Singapore” – was printed that same day on 1 January 1823 and Abdullah’s suggestion that it was the regulation on the prohibition of gambling was most likely wrong as this was printed some time later in May 1823. Some academics report the publication date as 31 December 1822 as printing began the night before as described in the Hikayat Abdullah. Leona O’Sullivan mentions a proclamation written on 2 December 1822. See O’ Sullivan, L. (1984). The London Missionary Society: A written record of missionaries and printing presses in the Straits Settlements, 1815–1847. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 57 (2 (247)), 61–104, p. 74. Call no.: RCLOS 959.5 JMBRAS) ↩

-

Hill, A.H. (1955, June). The Hikayat Abdullah. Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 28 (3 (171)), 3–354, pp. 165–166. Call no.: RCLOS 959.5 JMBRAS ↩

-

Today, Lower Saxony is part of Germany although for some time in the 19th century, it was part of Denmark. This is why Thomsen is sometimes referred to as German and at other times, Danish. ↩

-

According to A.H. Hill, Thomsen was in the Dutch East Indies prior to his arrival in Malacca in 1815 and had likely picked up Indonesian Malay there, which is distinct from the Malay spoken in the Peninsula. This may account for Thomsen’s claims in having prior knowledge of the Malay language and Abdullah’s frustrations in teaching him the language. See Hill, Jun 1955, p. 291. ↩

-

Milner, A.C. (1981, June). Notes on C.H. Thomsen: Missionary to the Malays. Indonesia Circle, 25. Retrieved Francis and Taylor Online. ↩

-

Philip, R. (1840). The life and opinions of the Rev William Milne, D.D. missionary to China (p. 197). Philadelphia: Herman Hooker. Call no.: RRARE 266.02341051 PHI ↩

-

Morrison, E. (1839). Memoirs of the life and labours of Robert Morrison (Vol 1, p. 355). London: Longman, Orme, Brown, Green and Longmans. Call no.: RRARE 266.02341051092 MOR ↩

-

Ibrahim bin Ismail. (1980). Early Malay printing in the Straits Settlements by missionaries of the London Missionary Society (pp. 43–44, 48). MA Thesis in Library and Information Studies, School of Library, Archive and Information Studies, University College London. Call no.: RSING 686.209595 IBR; Gallop, A.T. (1990). Early Malay printing: An introduction to the British Library Collections. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 63 (1 (258)), 85–124, p. 95. Call no.: RCLOS 959.5 JMBRAS ↩

-

Harrison, B. (1979). Waiting for China: The Anglo-Chinese College at Malacca, 1818–1843, and early nineteenth-century missions (pp. 30–31). Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. Call no.: RSING 207.595141 HAR ↩

-

Ibrahim, 1980, pp. 44–45; O’Sullivan, 1984, p. 71. ↩

-

O’Sullivan, 1984, p. 73. ↩

-

Many of Thomsen’s works were translated with much help from Munshi Abdullah. ↩

-

Ching, S. (1996). Printing presses of the London Missionary Society among the Chinese (p. 127–128) [PhD dissertation]. London: University College of London. Retrieved from UCL Discovery website. ↩

-

Hill, Jun 1955, p. 18; Raffles, S. (1830). Memoir of the life and public services of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles (pp. 536–537). London: John Murray. Call no.: RRARE 959.570210924 RAF ↩

-

O’Sullivan, 1984, pp. 74–78. [Raffles wrote on 5 January 1823 that he had “a press going in English & Malay”. See Bastin, 1981, p. 17.] ↩

-

Byrd, C.K. (1970). Early printing in the Straits Settlements, 1806–1858 (p. 13). Singapore: Singapore National Library. Call no.: RSING 686.2095957 BYR ↩

-

O’Sullivan, 1984, p. 86. ↩

-

O’Sullivan, 1984, pp. 86, 90; Ching, 1996, pp. 112, 126–127. [On 27 November 1832, Thomsen returned this small wooden press to Penang at the request of the LMS.] ↩

-

Ching, 1996, p. 158 ↩

-

O’Sullivan, 1984, pp. 78–79; Ching, 1996, pp. 159–160. [Milton left the mission but not Singapore, remaining there until his death in 1849.] ↩

-

Ching, 1996, pp. 63, 154–155, 445. ↩

-

O’Sullivan, 1984, p. 74. ↩

-

Bastin, J.S. (2014). Raffles and Hastings: Private exchanges behind the founding of Singapore (pp. 216–217). Singapore: National Library Board and Marshall Cavendish Editions. Call no.: RSING 959.5703 BAS ↩

-

The only known complete work for the 1827 edition is found in the Singapore/Malaysia Collection at the National University of Singapore Library. See National University of Singapore. (2011, September 6). The Singapore/Malaysia Collection. Retrieved from National University of Singapore website. ↩

-

Noorduyn, J. (1957). C. H. Thomsen, the editor of “A Code of Bugis Maritime Laws”. Bijdragen tot de Taal-,Land- en Volkenkunde, 113 (3), 238–251, pp. 246–247. Call no.: RUR 572.9598 ITLVB ↩

-

O’Sullivan, 1984, pp. 82, 102; Noorduyn, 1957, p. 248 ↩

-

The National Library, Singapore, has a copy of this first edition. ↩

-

Tomlin, J. (1844). Missionary journals and letters (pp. 293–294). London: James Nisbet and Co. Call no.: RRARE 266.3 TOM ↩

-

The Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle (Vol 12, p. 165). (1834). London: Frederick Westley and A.H. Davis. Retrieved from Hathi Trust Digital Library website. ↩

-

Ching, 1996, pp. 161–162, 164. ↩

-

O’Sullivan, 1984, p. 80; Ibrahim, 1980, p. 82. ↩

-

Thomsen’s connection with the LMS ceased thereafter and little is known of his further endeavours or even death date. See Whitehouse, J.O. (1896). Register of missionaries deputations, Etc 1796–1896 (p. 30). London: London Missionary Society. Retrieved from Hathi Trust Digital Library website. ↩

-

Church Missionary Society. (1835). Missionary register (Vol. 23, p. 95). London: Seeley, Jackson & Halliday. Retrieved from Hathi Trust Digital Library website. ↩

-

O’Sullivan, 1984, p. 73. ↩

-

Church Missionary Society. (1825). Missionary register (Vol. 13, p. 387). London: Seeley, Jackson & Halliday. Retrieved from Hathi Trust Digital Library website. ↩

-

Bastin, J. (1983). The missing second edition of C.H. Thomsen and Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir’s English and Malay vocabulary. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 56 (1 (244)), 10–11, p. 10. Call no.: RCLOS 959.5 JMBRAS ↩

-

Proudfoot, I. (1993). Early Malay printed books: A provisional account of materials published in the Singapore-Malaysia area up to 1920, noting holdings in major public collections (p. 550). Kuala Lumpur: Academy of Malay Studies and the Library, University of Malaya. Call no.: RSING 015.5957 PRO ↩

-

Ching, 1996, p. 150; Harrison, 1979, p. 125; Proudfoot,1993, p. 550. ↩

-

For more information on the publication, see Ong, E.C. (2016, January–March). A Christian sermon in Malay. BiblioAsia, 11 (4), 96–97. Call no.: RSING 027.495957 SNBBA-[LIB]; O’Sullivan, 1984, p. 72. ↩