Surviving the Japanese Occupation: War and its Legacies

A revamped exhibition space opens at the old Ford Factory in Bukit Timah, marking the 75th anniversary of the fall of Singapore. Fiona Tan details its major highlights.

Facade of the old Ford Factory on Upper Bukit Timah Road. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Facade of the old Ford Factory on Upper Bukit Timah Road. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Along a relatively quiet stretch of Upper Bukit Timah Road, now dwarfed by high-rise condominiums, stands the Art Deco façade of the old Ford Factory – built in 1941 and designed by the French structural engineer Emile Brizay as Ford Motor Work’s first car assembly plant in Southeast Asia.

Part of the original building was torn down when the area was redeveloped in the mid-1990s, but the main structure, housing the very spot where the British Lieutenant-General Arthur E. Percival surrendered to Lieutenant-General Tomoyuki Yamashita, commandant of the Japanese forces, on 15 February 1942, has been preserved.

“The Meeting of General Yamashita and General Percival” (1942), an oil painting by Saburo Miyamoto. All rights reserved. Tan, S.T.L., et al. (2011). Battle for Singapore: Fall of the Impregnable Fortress (Vol. 1). Singapore: National Archives of Singapore.

“The Meeting of General Yamashita and General Percival” (1942), an oil painting by Saburo Miyamoto. All rights reserved. Tan, S.T.L., et al. (2011). Battle for Singapore: Fall of the Impregnable Fortress (Vol. 1). Singapore: National Archives of Singapore.That fateful event was preceded by a week of intense fighting, dubbed “The Battle of Singapore”, between the combined British and Allied forces and Japanese troops after the latter made landfall on the northwestern coastline near the Johor Strait. Percival made the fatal error of assuming that the Japanese would attack from the northeastern coastline and had his firepower and soldiers concentrated along that front. The rest, as they say, is history.

A New Exhibition Opens

The Former Ford Factory – as the building is officially known − was gazetted as a national monument on 15 February 2006, following its conversion into a World War II exhibition space by its custodian, the National Archives of Singapore (NAS). Memories at Old Ford Factory (MOFF) operated for a decade until it closed in February 2016 for a major revamp.

Now, after a year-long refurbishment, the MOFF reopens as the Former Ford Factory, featuring refreshed content and a new focus. The exhibition highlights a new area of focus by looking at the impact of the war and the Occupation years, including the immediate and longer-term legacies of this period on Singapore and the region.

Back in 1981, seeing the dearth of written records left behind by the Japanese administration during the three-and-a-half years it occupied Singapore, the NAS, under its then Director Lily Tan, “embarked on a project to collect oral recordings and to look for documents, photographs and all kinds of paraphernalia related to the war and the Occupation”.1

More than three decades after Tan made that call, the NAS has amassed a significant collection of personal records and oral histories on this subject. Over the years, many researchers have been using these sources to reconstruct authentic accounts that have significantly enriched our understanding of life in Singapore during the Japanese Occupation.

The lack of sufficient documentation from this period, however, remains a persistent black hole, which is why NAS continues the effort to collect oral histories and personal records relating to people’s experiences of the war and the Occupation.

One such programme was the Call for Archives in March 2016, which saw over 400 items donated by members of the public, some of which will be on display in the revamped exhibition. NAS continues to welcome donations of historical significance from the public so that these can be preserved for the generations to come.

As we approach the 75th anniversary of the fall of Singapore on 15 February 2017, it is timely to revisit these memories and experiences.

Highlights of the Exhibition

The revamped exhibiton showcases the British surrender, the subsequent Japanese Occupation years, and the legacies of the war. Through oral history accounts and archival records from the collections of NAS, the National Library, Singapore, partner agencies and private collectors, this new exhibition aims to capture the diverse experiences of people who lived through this crucial period of our history.

The exhibition features a wide range of material, from government records and oral history interviews to maps and records from private collectors, including cherished personal documents and artefacts from individuals who have kept these items all these years because of the memories – however painful or traumatic – they represent. Overall, the displays balance bigpicture overviews of major events interspersed with deeply personal stories and asides.

The first thing a visitor sees upon entry to the lobby are displays that set the scene of pre-war Singapore and highlights the history of the Former Ford Factory. The exhibition space proper is broadly divided into three zones:

- Fall of Singapore: Outlines the events leading up to that fateful moment where British forces surrendered unconditionally to the Imperial Japanese Army in the Ford Factory boardroom.

- Becoming Syonan: Captures the diverse experiences of people during the Japanese Occupation.

- Legacies: Highlights the various legacies of war and Occupation in Singapore, from the political and social changes that arose and the ways we remember the war in Singapore today.

In total, there are over 200 exhibits on display at the exhibition. As it is not physically possible to cover all the exhibits within the confines of this article, we highlight a small selection here.

Fall of Singapore

Featuring the three intertwining narratives of Japanese military aggression, British defences and the civilians in Singapore caught up in these larger forces of empire and war, this section of the exhibition provides visitors with fresh perspectives into what Winston Churchill – the British Prime Minister during the war years – proclaimed as the “worst disaster and largest capitulation in British history”.

Graduation yearbook of the Chinese Military Academy

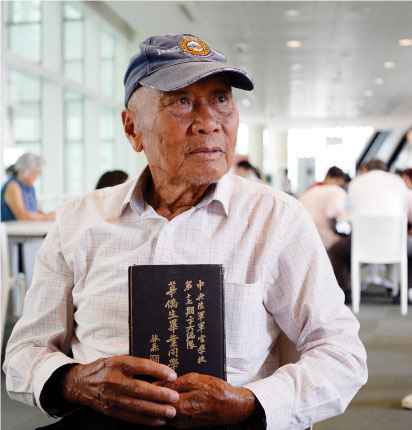

One of the highlights of this section is a graduation yearbook of the Chinese Military Academy (1940), which belongs to 96-year-old Lim Kheng Jun.

Even before the war descended on Southeast Asia, the Chinese community in Singapore had already been mobilised to help China in the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–45). In addition to raising funds through the Singapore China Relief Fund Committee, overseas Chinese also contributed their services. For instance, over 3,000 people from Malaya and Singapore volunteered as drivers and mechanics, braving the treacherous 1,146-km-long Yunnan–Burma Road, to transport military and aid supplies to the battle front.

Others like Lim Kheng Jun enlisted in the Chinese Military Academy (中央陆军军官学校) in 1939. Lim was trained in China as an intelligence officer, and later, as a police officer deployed to Beiping and then Hainan. In March 2016, Lim responded to the open call for archive materials for the exhibition, bringing along his treasured copy of the yearbook as well as personal records of his involvement in the Sino-Japanese war.

Lim Kheng Jun pictured here with his graduation yearbook at the public Call for Archives event held at the National Library Building on 12 March 2016.

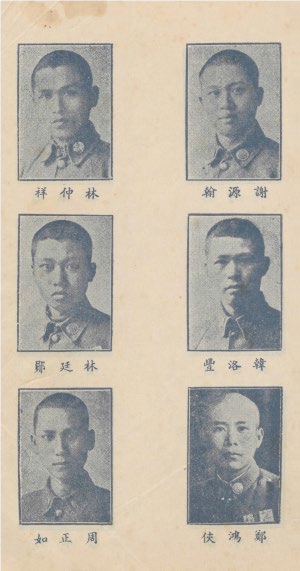

Lim Kheng Jun pictured here with his graduation yearbook at the public Call for Archives event held at the National Library Building on 12 March 2016. Lim Kheng Jun as a young soldier in 1940 (second row, on the left), p. 117.

Lim Kheng Jun as a young soldier in 1940 (second row, on the left), p. 117. Japanese intelligence map of Singapore

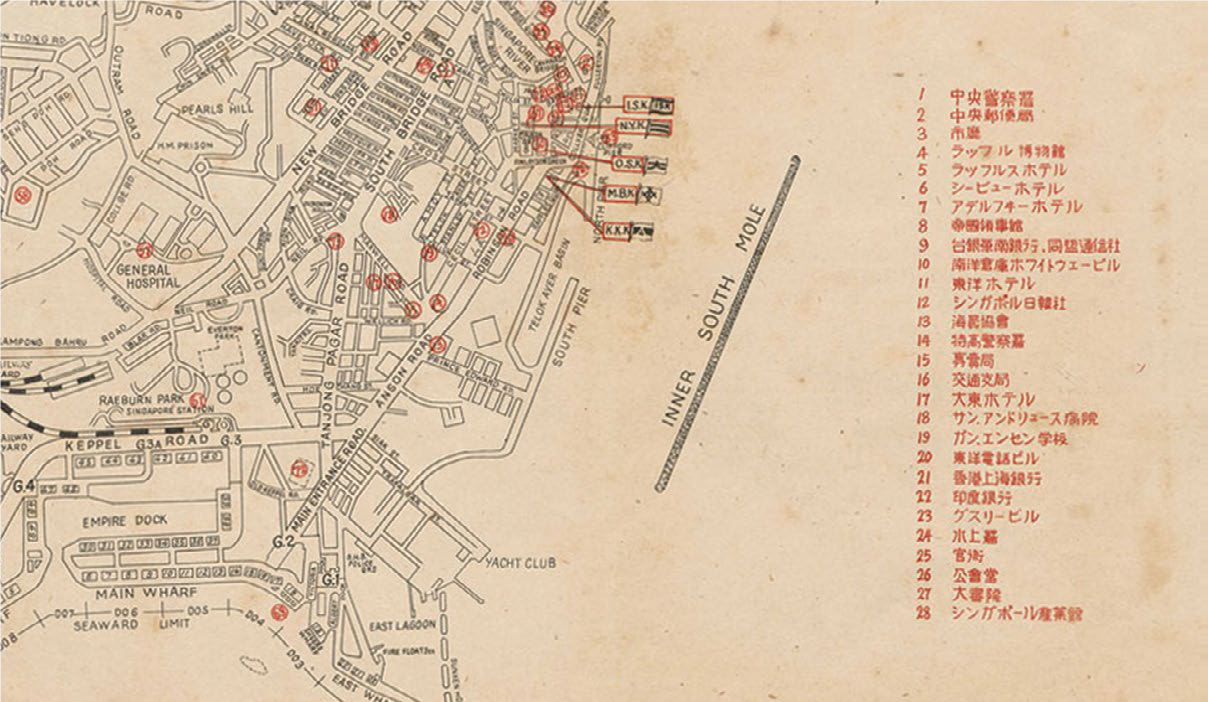

Another item of note – donated by Lim Shao Bin to the National Library − is a Japanese intelligence map of Singapore. It is accompanied by a booklet with 83 key locations marked up in red.

As the Japanese military prepared to advance into Southeast Asia, the chief planner of the Malayan Campaign, Lieutenant-Colonel Masanobu Tsuji, hired Japanese who were living in Singapore as informants. The Japanese military also sent “observation staff” to carry out espionage work in Malaya and Singapore in the late 1930s.

This map and its accompanying booklet contain annotated photographs of 83 key locations in Singapore town that were photographed and documented by Japanese informants before the war. These documents highlight important commercial and government buildings, such as police stations and municipal buildings. Japanese-owned businesses, such as shipping lines, were also identified on the map, enabling the Japanese intelligence to identify locations with Japanese interest and spare them from attacks during the invasion.

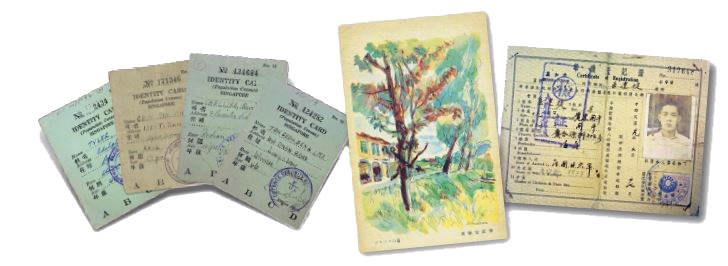

Identity cards issued under the Defence (Security Registration) Regulations

As the war in China waged on and hostilities in Europe broke out, the British colonial administration began to prepare the local population for the possibility of war in Malaya. Initially, the preparations were subtle, such as familiarising the public with air raid precautions and basic civil defence skills, but from 1941 onwards, the war preparations became more overt with screening of the population and recruiting locals to join the military.

In that same year, it became compulsory for all non-military residents of Singapore to carry identity cards under the Defence (Security Registration) Regulations.2 These cards – that allowed the government to screen the population for potential spies – were among the first ominous signs of the looming war.

Japanese artistic impressions of occupied Singapore

Also found in this section of the exhibition are sensō sakusen kirokuga (war campaign documentary paintings). A few months before the fall of Singapore, the Japanese military administration started to send prominent Japanese artists to various parts of Southeast Asia to paint scenes of war based on photographs or after talking to soldiers on the ground.

These depictions of war, which took the form of postcards and paintings, were distributed to Japanese soldiers and exhibited both in the newly conquered territories and in Japan to highlight the bravery of the military.3

There are five postcards and two watercolour paintings on display, donated to the NAS by Taka Sakurai, formerly an officer with the propaganda department of the Imperial Japanese Army. Sakurai produced these postcards based on artists’ impressions of scenes of Singapore after the fighting ceased. The postcards were then distributed to Japanese soldiers to commemorate their victory.4

Becoming Syonan

On 18 February 1942, Singapore was officially renamed Syonan-to, meaning “Light of the South”. The Japanese Occupation was a grim period in our history. From the acts of state-sanctioned violence to grandiose promises as part of the “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere”, this section of the exhibition showcases the experiences of people living under a new administration as well as the acts of resistance by those who chose to fight back and make a stand.

“Screened” stamp

One of the first actions by the Japanese military in Syonan was a mass screening or dai kenshō (大検証; “great inspection”), which the Chinese later referred to as Sook Ching (肃清). Such screenings to identify anti-Japanese elements in the population had been carried out whenever Japan conquered new territories in China. Three days after the British surrender in Singapore, Chinese males aged between 18 and 50 were ordered to report to screening centres − and in the confusion, some women and children went as well.5

At the reporting centres, those who received a stamp with the character “検” (or “examined”) were allowed to leave. Some people brought Overseas Chinese registration passes issued by the Chinese consulate in the pre-war period and had them stamped; while others recounted getting stamped on their T-shirts, other personal identification documents, or even on parts of their body.

One survivor recounted:“When I went home, I had the rubber stamp with the word “cleared” [“検”] or something like that. I made sure that the stamp lasted as long as possible. So washing my hands, whenever I took my bath, I got to raise my arm up to make sure the stamp there was not washed away… Wherever you go, you have to show your arm to the Japanese soldiers.”6

Apart from displays of such documents, the exhibition also allows visitors to experience first-hand accounts of Sook Ching survivors by listening to oral history excerpts.

Case of Joseph Francis

Stories of deprivation, suffering and torture were part of the fabric of the Syonan-to years, experienced by both the local civilian population as well as British and Allied soldiers.

One particular story stands out. On 27 September 1943, six Japanese oil tankers were destroyed at Keppel Harbour and suspicion fell upon the prisoners-of-war (POWs) interned in Changi Prison, who were thought to have transmitted news to the raiding party.

Joseph Francis, who worked as a driver for a Japanese inspector at the POW camp, was caught for passing information and a secret transmitter to the prisoners. In the ensuing raid that took place at Changi Prison, many POWs were rounded up for interrogations. Several civilians too were arrested, including Francis, who was tortured by the kempeitai (Japanese military police) over a six-month period.

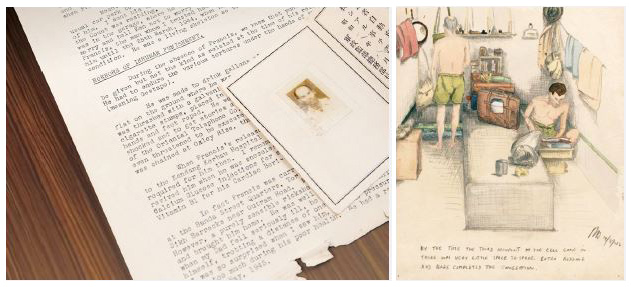

On his release, Francis required extensive medical care and he eventually died in May 1945. After the Occupation, his brother and friends wrote to the British Military Administration, describing in detail Francis’ contributions to the anti-Japanese resistance. On display at the exhibition is Francis’ driver’s licence and the letter written by his friend, Kenneth Tay, describing the “horrors of inhuman punishment” that Francis endured at the hands of his captors, that had reduced him into a pitiable “living skeleton”.

Sketches by William Haxworth

Also worth seeing are the selection of sketches, drawn from a collection of over 300 that were secretly sketched by former police inspector William R.M. Haxworth during his internment at Changi Prison and Sime Road Camp. The sketches depict the crowded and unsanitary living conditions at the camps, and capture the internees’ decline in health and weight over time. Several sketches reveal Haxworth’s ability to find humorous moments and comic relief through his art in spite of the difficult circumstances.

After the war, Haxworth rejoined the police force and stayed there until his retirement in 1954. In 1986, one year after he passed away, his wife donated his entire set of sketches to the NAS.

Legacies of War and Occupation

On 5 September 1945, the British returned to Singapore to great relief and rejoicing among the people. However, the initial euphoria soon waned: the wartime experience and the subsequent problems the local population faced, coupled with the inability of the British Military Administration (BMA) to deal with the issues competently, left the people with a less rosy view of the British.

For six months after the Japanese surrender, Singapore and Malaya were run by the interim BMA. People nicknamed it the “Black Market Administration” because it was plagued by corruption and inefficiency. Nonetheless, the BMA, despite difficult post-war conditions, did the best it could to restore public utilities and services, distribute war relief, and ease conditions for business and social activities.

The legacies of war were manifested at various levels − from grand British plans for decolonisation and the social challenges of postwar reconstruction to the political awakening of the people across the political spectrum.

Rounding off the final section of the exhibition is a reflective space where visitors are encouraged to consider how they remember the war and its legacies.

Post-war policies

There were significant shifts in terms of social policy in the immediate post-war years. The colonial government adopted a more involved approach to education, housing, health care and social welfare in Singapore, in line with the moderate socialist approach of post-war Britain. These moves were also part of the plan to unite Singapore’s plural society in preparation for decolonisation.

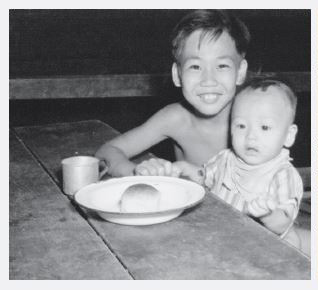

A Department of Social Welfare, for instance, was set up in in June 1946 to continue the BMA’s work of tackling the lingering social problems caused by the Occupation. The department set up free feeding centres for children, as well as “People’s Restaurants”, where anyone could buy a cheap and nutritious lunch for 35 cents (later, 8-cent meals were introduced to help the urban poor).7

Children’s feeding centre in the post-war period. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Children’s feeding centre in the post-war period. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Poster to protest arrests of communists

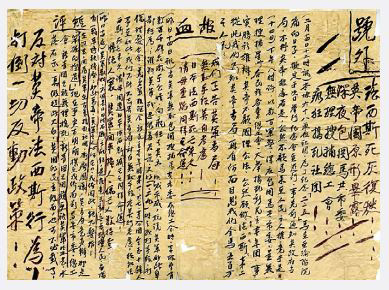

One of the most profound changes of the war and Occupation was the realisation that the British did not have an inalienable right to rule Singapore. This political awakening coupled with the success of the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army during the Occupation resulted in communism gaining traction as a political ideology in the post-war years.

Written with blood and Chinese brush ink, this poster (see image below) was created as a means of protest against police raids on the Malayan Communist Party and other pro-communist organisations on the eve of the 15 February demonstrations in 1946. The communists had organised the agitations as part of their plan to undermine the British. While the demonstrations were ostensibly meant to commemorate the fall of Singapore, the British authorities viewed it as an insult as it was on this day in 1942 that they had surrendered to the Japanese.

A poster written with blood and Chinese brush ink protesting the arrest of members of the Malayan Communist Party in 1946. Courtesy of the Ministry of Home Affairs, Internal Security Department Heritage Centre.

A poster written with blood and Chinese brush ink protesting the arrest of members of the Malayan Communist Party in 1946. Courtesy of the Ministry of Home Affairs, Internal Security Department Heritage Centre.In 1948, the Malayan Communist Party abandoned the “united front” strategy of peaceful struggle and pushed for an armed struggle, leading the British to declare a state of Emergency. The ensuing clashes between communists and the colonial government would have far-reaching consequences in shaping the post-war political landscape in Singapore and Malaya.

351 Upper Bukit Timah Road, Singapore 588192

Mondays to Saturdays, 9am – 5.30pm

Sundays, 12 noon – 5.30pm

Daily guided tours are available.

Visit https://corporate.nas.gov.sg/former-ford-factory/overview/ for more information.

Fiona Tan is an Assistant Archivist with the Outreach Department, National Archives of Singapore, where she conducts research to promote a greater awareness of its collections.

Fiona Tan is an Assistant Archivist with the Outreach Department, National Archives of Singapore, where she conducts research to promote a greater awareness of its collections.Notes

-

Foreword to The Japanese Occupation: Singapore 1942–1945. (1985). Singapore: Archives & Oral History Department. Call no.: RCLOS q779.995957 JAP ↩

-

Public & security registration. (1941, December 27). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Tsuruya, M. (2005). Sensō sakusen Kirokuga (War campaign documentary paintings): Japan’s national imagery of the “Holy War”, 1937–1945, pp. 1–3 (Doctoral dissertation, School of Arts and Sciences, University of Pittsburgh). Retrieved from University of Pittsburg website. ↩

-

Yeo, C. (Interviewer). (2006, June 30). Oral history interview with Taka Sakurai [Transcript of Recording no. 003068/03/03, pp. 1–64]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

W.K. (2001, April 11). Justice done? Criminal and moral responsibility issues in the Chinese massacres trial Singapore, 1947, pp. 3–4 (Genocide Studies Program Working Paper No. 18, Branford College, Yale University). Retrieved from the Battle of Manila Online website. ↩

-

Chua, S.K. (Interviewer). (1982, February 2). Oral history interview with Heng Chiang Ki [Transcript of Recording No. 000152/08/02, pp. 20–21]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Ho, C.T. (2013, April 3). Taking care of its own: Establishing the Singapore Department of Social Welfare, 1946–1949, pp. 12–13. Retrieved from Academia website. ↩