Windows into History

Drawings discovered in a Belgian archive help fill gaps in the history of stained glass windows in Singapore. Yeo Kang Shua and Swati Chandgadkar reveal their findings.

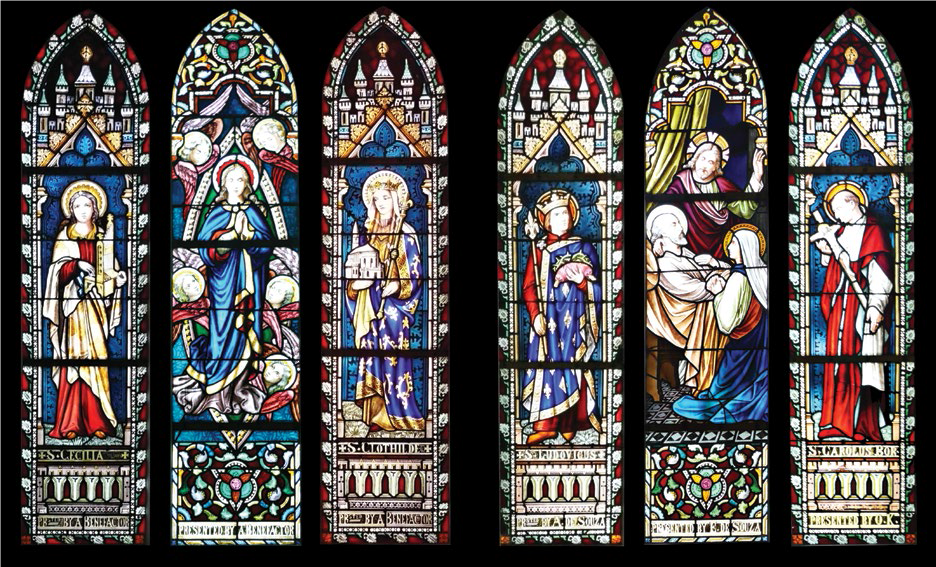

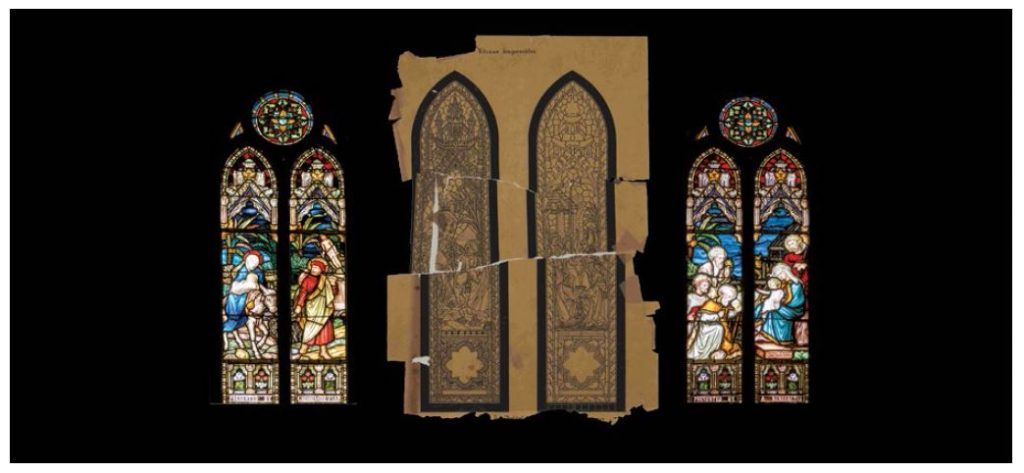

Triptych windows found in the side chapels at the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus. From left to right: St Cecilia, St Mary and St Clothilde (left chapel); and St Louis, The Death of Saint Joseph, and St Charles Borromeo (right chapel). Courtesy of Swati Chandgadkar.

Triptych windows found in the side chapels at the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus. From left to right: St Cecilia, St Mary and St Clothilde (left chapel); and St Louis, The Death of Saint Joseph, and St Charles Borromeo (right chapel). Courtesy of Swati Chandgadkar.Light can be soft, quiet, or at times dramatic, depending on the time of the day and year. Since time immemorial, builders have used architecture to modulate natural light and create emotional – and even spiritual – experiences for people.

The use of coloured glass in building facades is a particularly powerful architectural tool. Originating in the Gothic churches of Medieval Europe, stained glass windows continue to be used in contemporary times by architects, often with striking results.

Ecclesiastical stained glass, in addition to its aesthetic quality, served another function: to narrate Christian stories. During the Middle Ages, these figurative windows were a means to teach the largely illiterate congregations about the Bible and the lives of saints. Stained glass windows tell other stories too by shedding light on social histories and patterns of patronage. The history of stained glass windows is thus rooted in Christianity as well as in architecture.

Stained Glass in Singapore

It is no accident that many of Singapore’s early churches and Christian institutions were clustered near the city centre. Located close to the “Ground Reserved by Government” and “European Town and Principal Mercantile Establishments” as seen in the 1823 “Plan of the Town of Singapore” by Lieutenant Philip Jackson, these structures served the religious and educational needs of the Christian communities.1

The Armenian Church of St Gregory the Illuminator on Armenian Street, St Andrew’s Cathedral on St Andrew’s Road, the Cathedral of the Good Shepherd, the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus (CHIJ, today a commercial complex known as CHIJMES) and St Joseph’s Institution (now Singapore Art Museum) along Bras Basah Road, St Joseph’s Church on Victoria Street and the Church of Saints Peter and Paul on Queen Street are some of Singapore’s most historically significant Christian sites. (The chapels at the former CHIJ and St Joseph’s Institution have been deconsecrated and are no longer used as places of worship today.)

All are Catholic institutions except the Armenian Church and St Andrew’s Cathedral, which are Oriental Orthodox and Anglican respectively. With the exception of the Armenian Church, all are embellished with stained glass windows.

The stained glass windows in this historic cluster provide more than just architectural interest. Many windows in these churches were “memorial panels” bearing names of their donors in the parish, and a number of these are stylistically similar. This observation has prompted several questions: Who made these windows? Who commissioned them? Were they made locally or imported?

Upon closer examination, the names of the donors are evident in many panels. Some windows also bear the signatures of the artisans or studios that produced them, as well as the year in which they were made. Many of these windows were made in Belgium and France, and date between 1885 and 1912, although some windows of later vintage can be found in these buildings too.

Three studio signatures are frequently inscribed on these window panels: “Vitrail St Georges, Lyon, France” and “J. Dobbelaere, Bruges, Belgium” in the CHIJ chapel; “J. Dobbelaere, Bruges, Belgium” in St Joseph’s Church; and “Martin Peintre, Angers, France” in the Church of Saints Peter and Paul. The windows in St Andrew’s Cathedral and the Cathedral of the Good Shepherd are unsigned, while the altar window in St Joseph’s Institution – believed to have been taken down during the Japanese Occupation (1942–45) – is now regarded as lost.2

Most of the windows at the CHIJ chapel and St Joseph’s Church were commissioned from the studio of Jules Dobbelaere. The Dobbelaere studio was established by Henri Dobbelaere in Walplaats, Bruges, in Belgium in 1860. Under his son, Jules Dobbelaere, the workshop reached new heights in stained glass production and found fame beyond the shores of Belgium.

Thus far, information on Dobbelaere’s work in Singapore has been scant. As part of our research, we located the online archives of the Dobbelaere workshop in 2009, which rest with the Documentation and Research Center on Religion and Society at the University of Leuven in Flanders, Belgium (hereafter “Leuven archives”). As the archiving and digitisation of these materials have progressed significantly, more information has since appeared online.

In early 2016, a formal request was made to the university to access the archives, which include drawings – known as “cartoons” in stained glass work – of the windows.

Relatively little is known about the studio of Martin Peintre in Angers, France, at this point. More information may surface in the future as historic materials are increasingly being made available online for research, as with the case of the Dobbelaere studio.

Of the three studios, Vitrail St Georges is by far the youngest. Founded by Joël Mône in 1979, the French studio claims its lineage from the studio of Jean-Baptiste Barrelon in Grigny, Lyon, which was established in 1852. Since 2010, the studio has been headed by Joël’s son, Jean.3 This was the studio that undertook the stained glass restoration when the CHIJ complex underwent extensive restoration between 1991 and 1996 and reopened as CHIJMES. The project was jointly overseen by the French architect Didier Repellin, and Ong and Ong Architects of Singapore.4

Henri Dobbelaere (fl. 1860–85)

The Dobbelaere studio was established by Henri Dobbelaere of Bruges, Belgium (b. 1822, d. 1885) in 1860.

Jules Dobbelaere (fl. 1885–1916)

Jules Dobbelaere (b. 1859, d. 1916) took over the workshop when his father Henri passed away in February 1885. Under his watch, theworkshop reached new heights in stained glass production and acquired international fame. The windows at St Joseph’s and CHIJ were commissioned during this time.

Justin Peene-Delodder (fl. 1919–29)

Jules passed away in 1916 without a male heir. In 1919, the workshop passed on to Justin Peene, a distant cousin of Jules’ daughters. He worked under the name Justin Peene-Delodder.

Weduwe Peene-Delodder (fl. 1929–38)

Justin’s wife, Alice Delodder, continued the workshop after his death in 1929, producing windows under the name Weduwe Peene-Delodder until 1938.

Andre Delodder-Peene (fl. 1938–53)

Andre Delodder, originally a cabinet maker, married Alice’s youngest daughter, Simonne Peene. He began working with his mother-in-law in 1936, and took on the family name two years later. His work appears under the name Andre Delodder-Peene.

Guy Delodder & son (fl. 1953–91)

Andre’s eldest son Guy Delodder took over the workshop in 1953. The sudden death of Guy Delodder’s successor (one of his four sons) in 1991 ended a tradition that had endured for five generations.

fl.=flourished

Above information from the University of Leuven’s Documentation and Research Center on Religion and Society.

The Importance of “Cartoons”

We all know of cartoons as animated films or humorous comic strips found in print. But in the art industry, a cartoon is a preliminary design made by an artist for a painting or other types of artwork such as a fresco, tapestry or stained glass window or panel. In stained glass windows, a cartoon delineates the theme of the window, the exact drawing (sometimes in colour), lead lines and all the stylistic details of the painting. In short, it is a blueprint for the stained glass window, prepared by the glass artist for the client’s approval, and used by the glazier who creates the actual window.

Cartoons are typically prepared by the stained glass artist; the glazier often advises where lead lines should be added to ensure the panel’s structural integrity. The cartoon is then copied onto tracing paper in full scale to create a working drawing or “tracing”.

Studios will usually keep cartoons and tracings for a pragmatic reason as it allows them to reuse these materials to create windows for other clients, making minor alterations where needed. Some of the older and more well-managed studios meticulously catalogue their glass work. This approach was adopted by many European studios and workshops in the 19th and early 20th centuries when markets opened up and glass makers began exporting their stained glass overseas, especially to the colonies.

Cartoons, therefore, address many crucial questions: where a window was made, for whom, by whom, how, in what social setting, in what style, and so on. A cartoon is literally a window into a window’s history.

Fortunately for us, the cartoons by the Dobbelaere studio have been preserved in the Leuven archives. By comparing these cartoons with the stained glass windows in Singapore’s historic buildings, we are better able to understand the history of these structures in relation to the stained glass panels as well as the communities who used these buildings as places of worship.

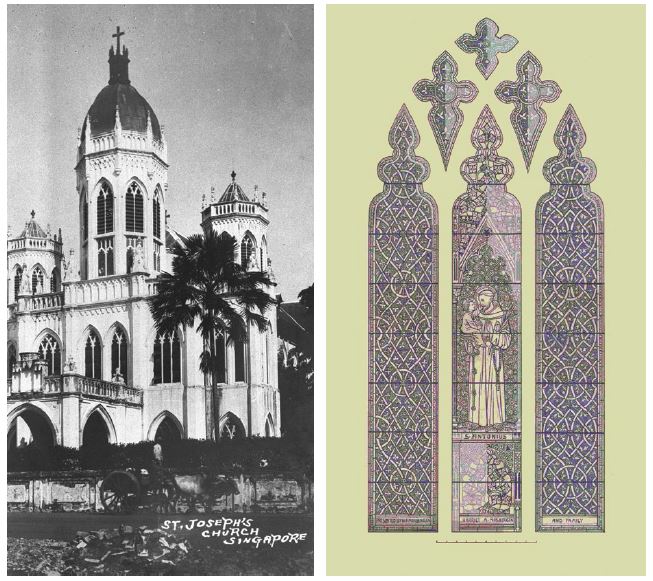

St Joseph’s Church

The five-sided apse (see text box below for an explanation of these architectural terms) of St Joseph’s Church on Victoria Street has beautiful ornamental and figurative stained glass windows, while two female saints are depicted in the transept windows. An article in the Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser in 1912 mentions that “the picture glass is by J. Dobbelaere of Bruges” but does not provide further details.5

With the exception of the “Sacr. Cor. Jesus” (Sacred Heart of Jesus) window in the centre of the apse, signed “J. Dobbelaere, Bruges, Belgium 1912”, none of the other figurative apsidal windows bear the studio’s signature. The other windows depicting “S. John Berchmans” (St John Berchmans), “S. Franc. Xav.” (St Francis Xavier), “Sta Maria” (St Mary), “Ste Joseph” (St Joseph), “S. Antoni” (St Anthony) and “Sancta Agnes” (St Agnes) are all unsigned.

In the Leuven archives, we were excited to find a Dobbelaere cartoon of the triptych window dedicated to “S. Antonius”. The cartoon clearly delineates the figure of St Anthony in the middle, with ornamental windows on either side.

Comparing this drawing with the extant window, it is clear that the design has been faithfully executed. The main ornamental elements, details of the drapery and the depiction of the Infant Jesus with St Anthony, are all in place. The extant window’s only departure from the cartoon is in the name plaque. It reads “S. ANTONI ORA P.N.” (“St Anthony, pray for us” in Latin), rather than “S. ANTONIUS” as in the cartoon. Although the window does not carry the studio’s signature, the cartoon is proof that the window was made in Jules Dobbelaere’s studio.

The transept window depicting “Sancta Catharina” (St Catherine) is unsigned, while the “Sancta Cecilia” (St Cecilia) window carries the signature and date: “J. Dobbelaere, Bruges, Belgium 1912”. The cartoon of the St Cecilia window is also kept in the archives, and the stained glass on site is a faithful rendition of the drawing, which includes decorative elements and the dedication “EX VOTO W.F. MOSBERGEN” (“An offering from W.F. Mosbergen”), presumably the donor.

It was not uncommon for studios or artists to sign just one window in a cluster of windows. Even today, most studios put their stamp on just one window even if their contribution consists of several panels. Minor elements outlined in cartoons are sometimes omitted in the final work. This happens for a number of reasons, one of which is lack of space during the execution.

Researchers must therefore undertake a comparative study of stained glass windows within the same building by examining the painting style, glazing technique, types of leads used, and the composition of the windows. These details help ascertain the studio or artist behind the windows. Looking at the style of the various apsidal windows, as well as the two transept windows, and armed with further evidence from the Dobbelaere cartoons, we can safely conclude that all the windows of St Joseph’s Church were produced by the workshop of Jules Dobbelaere.

CHIJ Chapel in CHIJMES

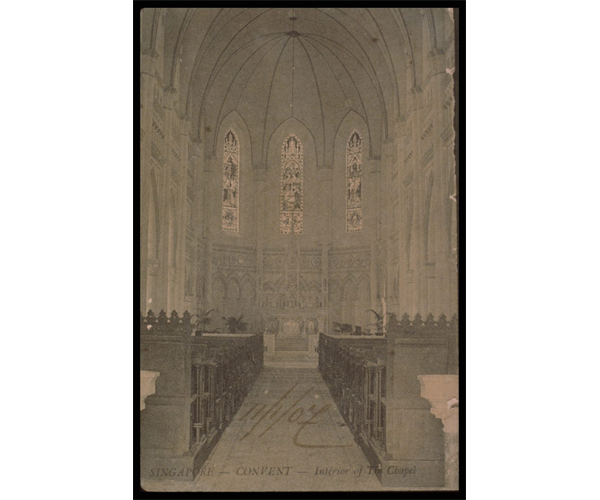

Interior view of the chapel at the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus (CHIJ) located at the corner of Bras Basah Road and Victoria Street. Designed by Father Charles-Bénédict Nain, the chapel was completed in 1903 and consecrated on 11 June 1904. Photo taken in the early 1900s. Arshak C. Galstaun Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Interior view of the chapel at the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus (CHIJ) located at the corner of Bras Basah Road and Victoria Street. Designed by Father Charles-Bénédict Nain, the chapel was completed in 1903 and consecrated on 11 June 1904. Photo taken in the early 1900s. Arshak C. Galstaun Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Many publications cite Father Charles- Bénédict Nain, a French priest of the Missions Étrangères de Paris (MEP) order, as the designer of the CHIJ chapel, with stained glass windows produced in Bruges, Belgium, by Jules Dobbelaere.6 Father Nain had been appointed as the assistant parish priest at the Cathedral of the Good Shepherd in 1898.

However, there is no indication which of the windows at the CHIJ chapel were produced by the Dobbelaere studio. Despite the large number of stained glass windows in the chapel, only two bear the signature “J. Dobbelaere, Bruges, Belgium”. Neither of these are dated.

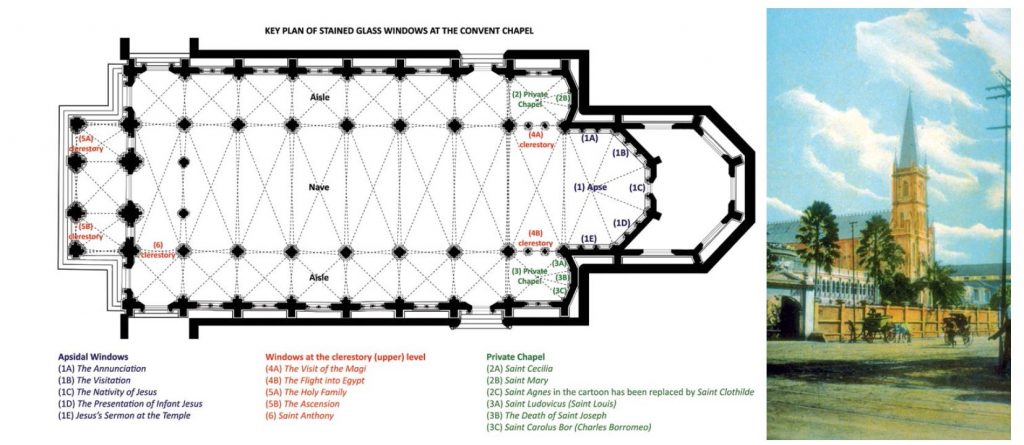

(Left) Floor plan of the stained glass in the chapel of the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus. Courtesy of Yeo Kang Shua.

(Left) Floor plan of the stained glass in the chapel of the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus. Courtesy of Yeo Kang Shua.A closer examination of the stained glass windows (see floor plan above) complicates the story further. Several windows bear the signature “Vitrail St Georges, Lyon, France”, and are dated “1994” – almost a full century after the chapel’s consecration. We know stained glass windows were already in place when the chapel was consecrated in 1904. A newspaper account dated 10 June 1904 described the windows as “most artistic”.7 How then do we explain the origins of these other windows, which bear a different signature and date?

A few sets of cartoons from the Leuven archives can be linked in terms of theme and composition with the existing windows on site: (1) one set of five cartoons for the apse; (2) one set of three cartoons for the private chapel to the left of the apse; (3) one set of three cartoons for the private chapel to the right of the apse; (4) one set of two cartoons for the clerestory on either side of the apse; (5) one set of two cartoons for the windows flanking a circular window in the gallery; and (6) one cartoon for the quatrefoil (four-cusped panel) in the gallery.

Comparing these cartoons with the chapel windows provides some insights.

Glass in the Apse

In the apse, all five extant lancet windows are based on themes outlined in the Dobbelaere cartoons of these windows.

Three of the five apsidal windows are direct adaptations of the Dobbelaere cartoons: The Nativity of Jesus (1C) “Presented by The Pupils of the Convent”; The Presentation of Infant Jesus (1D) “Presented by Benefactors of Manila”; and Jesus’s Sermon at the Temple (1E) “Presented by A.G. Pertille”. None of these windows is signed or dated, but the cartoons confirm that Jules Dobbelaere is their creator.

The other two apsidal stained glass windows located to the left of the apse when facing it – The Annunciation (1A) and The Visitation (1B) – are signed “Vitrail St Georges, 1994, Lyon, France”. Although these two windows bear the signature of another studio and a more recent date, it is obvious that the theme and composition are based on the original cartoons by Dobbelaere. The only difference is in the donor panels. These now read as “Presented by a Benefactor”, whereas the cartoons bear the inscriptions “Presented by P.S.R. Pasoual” and “Presented by the Ossorio Family” respectively.

Glass in the Two Private Chapels

In the private chapel to the left of the apse, we begin to see discrepancies in the triptych window.

The Dobbelaere cartoon shows three female saints: “S. Cæcilia” (St Cecilia, left); Saint Mary (not named in the panel, centre); and “S. Agnes” (St Agnes, right). The stained glass windows on site follow the cartoons in the placement of St Cecilia (2A) and St Mary (2B). But the cartoon’s St Agnes has been replaced by “S. Clothilde” (St Clothilde, 2C) on site.

The drapery of the St Cecilia and St Mary windows also differ from the cartoons, as does the position of St Mary’s hand. There are also fewer angels in the St Mary panel than in the cartoon.

All three windows now read “Presented by a Benefactor”, while the cartoons clearly bear the donors’ names: “Presented by D. De Souza”, “Presented by M.C.F. De Souza”, and “Presented by G. De Souza” respectively.

The Dobbelaere signature is absent in this stained glass triptych. Instead, both the St Cecilia and St Clothilde windows are signed “Vitrail St Georges, 1994, Lyon, France”. The St Mary window is unsigned.

In the private chapel to the right of the apse, the triptych window is a faithful realisation of the Dobbelaere cartoons without revisions: “S. Ludovicus” (St Louis, 3A) “Presented by A. De Souza”; The Death of St Joseph (3B) “Presented by E. De Souza”; and “S. Carolus Bor.” (St Charles Borromeo, 3C) “Presented by O.K.”. The latter bears the signature “J. Dobbelaere, Bruges, Belgium”. The cartoons allow us to confidently attribute these windows to the Dobbelaere studio.

Glass in the Clerestories

The cartoons for the two stained glass windows situated above the chancel at clerestory level shows two lancets: one depicting The Flight into Egypt, and the other The Visit of the Magi.

Each window, however, comprises a pair of lancet panels crowned by a roundel and three small insets to form a tracery. The cartoon’s themes remain, but the theme of each window is now spread over two lancet panels. The Visit of the Magi (4A) is on the left of the apse, and The Flight into Egypt (4B) on the right. This change may have been the result of revisions to the architectural design of the chapel, with the windows redesigned to adapt to the modified openings.

While neither cartoon indicates a donor’s name, The Visit of the Magi window now reads “Presented by a Benefactor”, while The Flight into Egypt is inscribed “Presented by Cheoug Quee Tiam”.8

Glass in the Gallery

Two sets of stained glass windows, each composed of a pair of lancet panels crowned by a roundel and three small insets to form a tracery, flank the circular window in the gallery. They are based on Dobbelaere’s cartoons, and have been reproduced faithfully without revisions. The window on the left is The Ascension (5B), with The Dove as Holy Spirit represented in the roundel. The lancets are inscribed “Presented by a Benefactor”. The window on the right is The Holy Family (5A), with Our Lord in Glory represented in the roundel. These lancets read “Presented by L. Scheerder”. The Ascension window is one of just two windows in the chapel that bears the signature “J. Dobbelaere, Bruges, Belgium”.

St Anthony is the subject of the quatrefoil on the left side of the gallery. The window is a perfect rendition of the original drawing in glass, faithfully following a beautifully coloured cartoon by Dobbelaere. The panel includes the name of the donors “Presented by Mr Nash Family”. Interestingly, this quatrefoil was catalogued in the archives as a window for the Cathedral of the Good Shepherd. This is likely to be a cataloguing error, we think, as the cartoon is undoubtedly for a window at the convent chapel.

Events that had taken place during CHIJ’s long but illustrious history provide further clues about these stained glass windows. One such event occurred on 15 February 1942 when Japanese forces invaded Singapore. During an air raid, several bombs fell within the vicinity of the convent, one of which damaged a number of windows.9 Accounts of the bombings do not mention which windows were damaged, nor do they record the extent of the damage. It is also unknown if any repairs were carried out after the war.

Tunneling works carried out for the construction of the Mass Rapid Transit system in the 1980s also had an impact on the chapel. Newspapers record mitigation works undertaken to protect the fragile windows, which were “boarded with wooden frames and covered in netting on both sides to try and protect them from damage.”10

CHIJ’s stained glass windows were eventually restored in the early 1990s when the convent building, including the chapel, underwent restoration. The restoration of the stained glass windows was carried out by Vitrail St Georges of France.

As noted earlier, there are a number of discrepancies between the cartoons and the extant windows, particularly in the side chapel to the left. Some of these windows now bear the signature of Vitrail St Georges. It is possible that these windows were badly damaged by the 1990s and required extensive reconstruction. It is unknown at this point if Vitrail St Georges had access to the Dobbelaere cartoons while undertaking the restoration, or whether its work was based on what remained of these windows.

Cathedral of the Good Shepherd

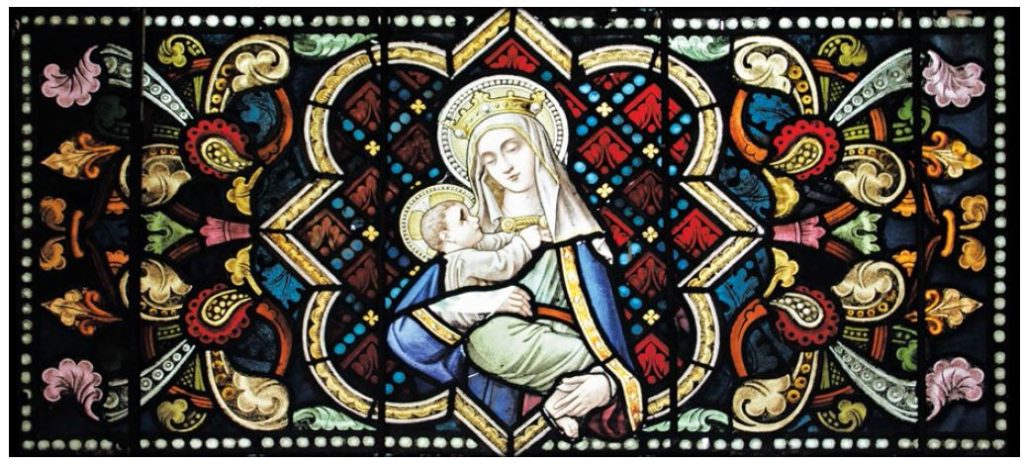

The Cathedral of the Good Shepherd has 14 stained glass fanlight windows or “lunettes” along the aisles and two figurative windows at the transepts. The fanlights are of two design typologies, while the figurative windows depict the Madonna and Child and St Joseph. All 16 windows are unsigned, with neither studio signature, date nor donor names inscribed on the panels.

There are few written references to the cathedral’s stained glass windows. One mention is found in a 1904 Straits Times article: “The Committee records with gratification, the beautiful gift of a set of stained glass for the Church windows by Bishop Bourdon.”11 The windows are not described further, making it difficult to ascertain if the bishop’s gift comprised solely of the fanlights, or if the gift included the two figurative windows too.

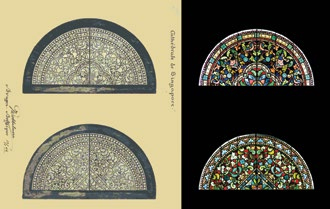

In the Leuven archives, we found Dobbelaere cartoons for the two different fanlight designs. One of the cartoons is a colour reference for the two designs. Comparing these cartoons with the fanlights in place today, there is little doubt that these windows were made by the Dobbelaere studio. The foliated design, composition, colour scheme and other painting elements seen in the stained glass windows are an exact reproduction of the cartoons.

More importantly, one of the cartoons is dated 1904, thereby confirming that the fanlights were gifts from the bishop, as mentioned in the newspaper article. As the cartoons for the two figurative windows were not found in the archives, their provenance remains indeterminate.

Cartoons for the fanlights or “lunettes” in the Cathedral of the Good Shepherd (left) and two of the windows as executed (right). Cartoons courtesy of KADOC – KU Leuven; photographs courtesy of Swati Chandgadkar.

Cartoons for the fanlights or “lunettes” in the Cathedral of the Good Shepherd (left) and two of the windows as executed (right). Cartoons courtesy of KADOC – KU Leuven; photographs courtesy of Swati Chandgadkar.St Joseph’s Institution

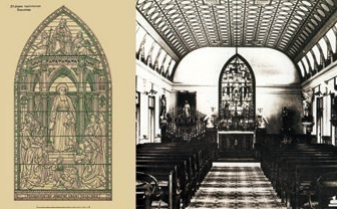

St Joseph’s Institution today houses the Singapore Art Museum. The chapel of this former school building was completed in September 1912. However, owing to a delay in the delivery of the stained glass window, the chapel – which now bears few traces of its ecclesiastical history – was dedicated only on 20 November that year.12

A modern glass and steel sculpture now sits in the opening where the stained glass window would have been located. With the exception of an old photograph of the chapel, which shows a faint silhouette of the stained glass window at the end of the nave,13 very little is known about the provenance or design of this historic window. A cartoon we found in the Leuven archives helps further our understanding of this window. The cartoon depicts St Jean-Baptiste de La Salle surrounded by pupils and members of the laity, with Mary and Jesus appearing on the mantle. The cartoon also bears the inscription “Presented by Joseph Chan Teck Hee”.

Cartoon from the Dobbelaere studio (left) and a historic photograph of the altar window at the chapel of St Joseph’s Institution (right). This cartoon is significant because prior to its discovery, the design of the window was unfortunately not documented in any form. The cartoon therefore provides a better understanding of what the lost window looked like. Cartoon courtesy of KADOC – KU Leuven; photograph courtesy of St Joseph’s Institution.

Cartoon from the Dobbelaere studio (left) and a historic photograph of the altar window at the chapel of St Joseph’s Institution (right). This cartoon is significant because prior to its discovery, the design of the window was unfortunately not documented in any form. The cartoon therefore provides a better understanding of what the lost window looked like. Cartoon courtesy of KADOC – KU Leuven; photograph courtesy of St Joseph’s Institution.The Dobbelaere cartoon fits the form and thematic outline with what we can see in the old photograph. It is therefore reasonable to infer that the cartoon is of the historic stained glass window of the school chapel, and more importantly, that it was executed by the studio of Jules Dobbelaere.

The discovery of the Dobbelaere cartoons in Leuven has provided valuable insights into the lineage of Singapore’s historic stained glass windows and sheds new light on their provenance.

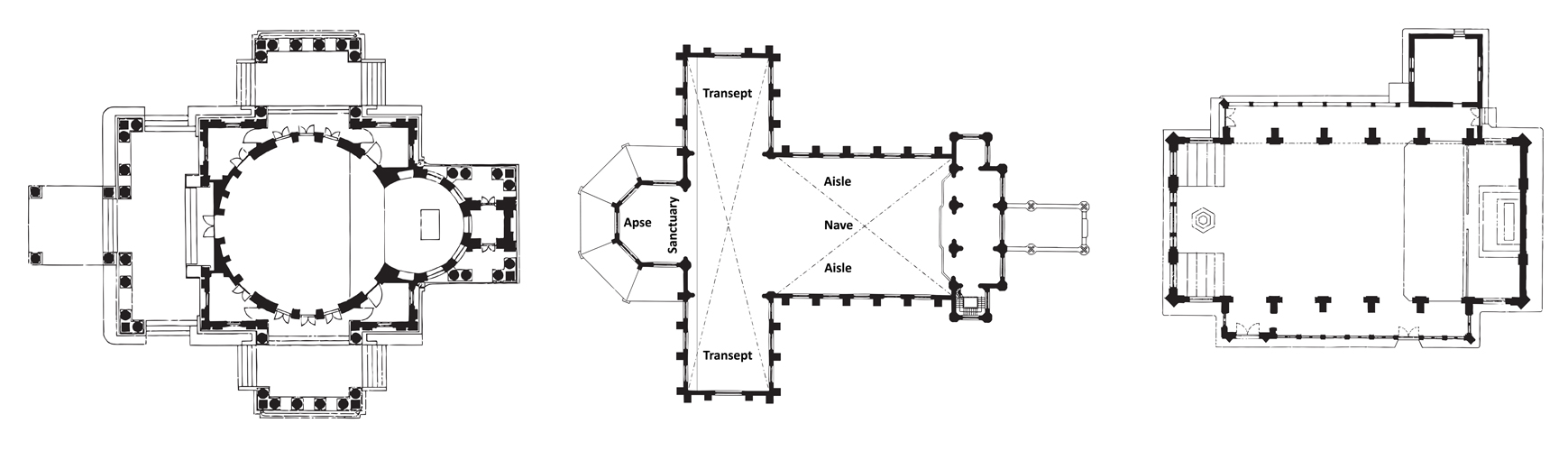

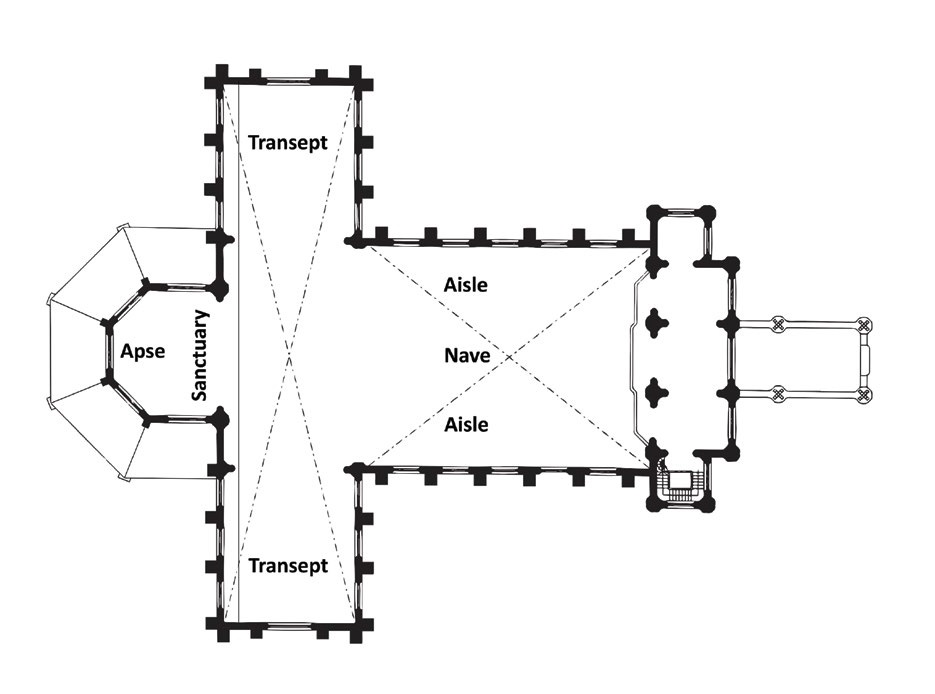

UNDERSTANDING CHURCH ARCHITECTURE

The footprint of a church is typically laid out in a rectangle, Greek-cross – a square central mass with four projecting arms of equal length – or Latin-cross cruciform plan. From these basic forms, an apse, which is a semicircular recess, may be attached behind the altar to provide a visual focus.

(From left to right) Greek cross plan of Armenian Church, rectangular plan of St George’s Church (at Minden Road) and Latin cross plan of Cathedral of the Good Shepherd.

The main body of the church, which is known as the nave, is the area where the congregation takes part in worship (called a mass in Catholic churches or service in the Protestant tradition).

A passageway to either side of the nave that is separated by a colonnade of columns or rows of pews is known as the aisle. A transept is the space that is perpendicular to the nave on either side of a cruciform.

Beyond the nave typically lies the sanctuary, usually separated from the nave by a step or altar rail, within which only the priests and their attendants are allowed. In Singapore, there are no churches with chancels – the space between the nave and the sanctuary that contain choir stalls or seats for the clergy.

In the case of St Andrew’s Cathedral, the choir stalls are positioned behind the altar. In Catholic churches, the tabernacle where the Eucharist14 is stored, is located behind the altar. In most cases, an apse is the recess behind the sanctuary.

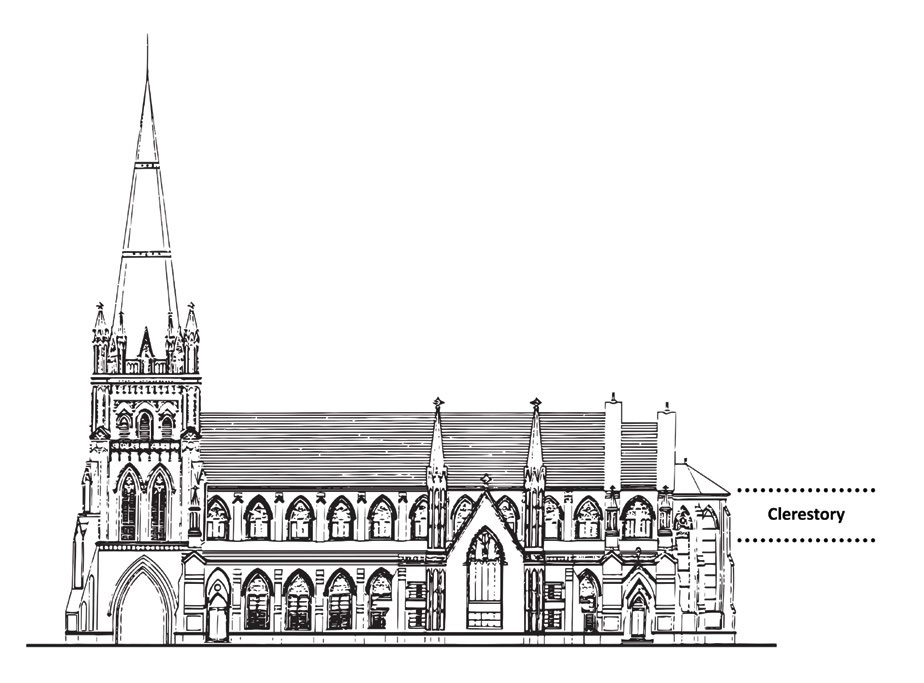

The clerestory denotes an upper level of the nave where the walls rise above the rooflines of the lower aisles and are punctuated with windows. Windows located in this area are also known as clerestory windows.

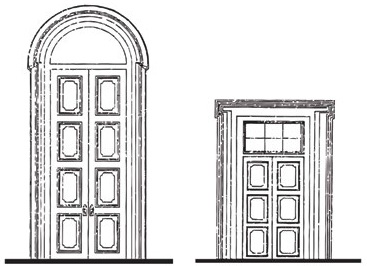

A fanlight or “lunette” is a semicircular window over a door or window. It is also sometimes known as a transom window, especially when it is rectangular in shape.

The stained glass windows located at the apse are also referred to as apsidal windows.

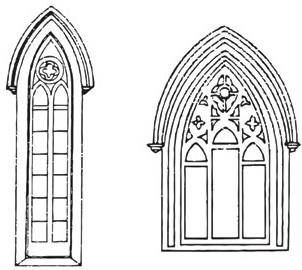

A lancet window (above left image) is a tall, narrow window with a pointed arch at its top. Such windows are typical of Gothic and neo-Gothic architecture.

A triptych is typically a work of art that is divided into three sections. A triptych window (above right image) likewise has a set of three window panels.

Readers who are interested in reading more about church architecture may refer to How to Read Churches: A Crash Course in Ecclesiastical Architecture by Denis Robert McNamara available at the library@orchard.15

The authors would like to acknowledge Wee Sheau Theng, Carolyn Lim, Soon-Tzu Speechley and Martina Yeo for their invaluable help in the course of this research.

Swati Chandgadkar is a stained glass conservator from Mumbai, India. She currently resides in Singapore.

Swati Chandgadkar is a stained glass conservator from Mumbai, India. She currently resides in Singapore.

Dr Yeo Kang Shua is an Assistant Professor at the Singapore University of Technology and Design, and holds the inaugural Hokkien Foundation Career Professorship in Architectural Conservation.

Dr Yeo Kang Shua is an Assistant Professor at the Singapore University of Technology and Design, and holds the inaugural Hokkien Foundation Career Professorship in Architectural Conservation.

-

Buckley, C.B. (1902). An anecdotal history of old times in Singapore: (With portraits and illustrations) from the foundation of the settlement under the Honourable the East India Company, on February 6th, 1819, to the transfer of the Colonial Office as part of the colonial possessions of the Crown on April 1st, 1867 (Vol. I, pp. 82–83). Singapore: Fraser & Neave Limited. Call no.: RRARE 959.57 BUC; Microfilm no.: NL 269 ↩

-

National Library Board. (2010) Former St Joseph’s Institution (Singapore Art Museum) written by Tan, Bonny. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia. ↩

-

Vitrail Center. (n.d.). Présentation de l’atelier de Lyon et de son savoire faire. Retrieved from Vitrail Center website; l’Institut Supérieur des Métiers. (2009–2016). Vitrail Saint-Georges. Retrieved from Enterprise du Patrimoine Vivant website. ↩

-

Pilon, M., & Weiler, D. (2011). The French in Singapore: An illustrated history(1819-Today) (pp. 195–196). Singapore: Editions Didier Millet. Call no.: RSING 305.84105957 PIL; Kong, L., Low, S.A., & Yip, J. (1994). Convent chronicles: History of a pioneer mission school for girls in Singapore (pp. 59–60). Singapore: Armour Publication. Call no.: RSING 373.5957 KON ↩

-

Untitled.(1912, June 27). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser(1884–1942), p. 414. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Meyers, E. (2004). Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus: 150 years in Singapore (p, 52). Penang, Malaysia: The Lady Superior of the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus. Call no.: RSING q371.07125957 MEY, Pilon & Weiler, 2011, pp. 108– 109; Kong, Low & Yip, 1994, pp. 59–60; Société MissionsÉtrangères. (1917). Missions-Étrangères: Compte-rendu des travaux de 1916 (p. 242). Paris: Séminaire des Missions-Étrangères. Not available in NLB holdings. ↩

-

New convent chapel. (1904, June 10). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

This is a spelling variation of “Cheong Quee Tiam”. ↩

-

Meyers, 2004, p. 60; Pilon & Weiler, 2011, p. 154; Kong,Low & Yip, 1994, pp. 103–105. ↩

-

CHIJ chapel reinforced for MRT work. (1986, July 28). The Straits Times, p. 11, CHIJ chapel’s stained glass windows are in danger. (1986, August 1). The Straits Times, p. 22; Aleshire, I. (1986, August 18). Experts warn of further damage to chapel windows. The Straits Times, p. 10; Goh, J. (1989, March 27). Urgent repairs needed on CHIJ chapel. The Straits Times, p. 19. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

S.C.C. lawn tennis tournament. (1904, May 14). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Brown, F. (1987). Memories of SJI: Reminiscences of old boys and past teachers of St. Joseph’s Institution, Singapore (p. 12). Singapore: St. Joseph’s Institution. Call no.: RSING 372.95957 BRO ↩

-

St. Joseph’s Institution. (n.d.). The SJI milestones. Retrieved from St. Joseph’s Institution website. ↩

-

The tabernacle is the box-like vessel in which the Eucharist – the consecrated bread and wine that is partaken as the body and blood of Jesus Christ or as symbols of Christ’s body and blood in remembrance of his death – is kept. ↩

-

McNamara, D.R. (2011). How to read churches: A crash course in ecclesiastical architecture. New York: Rizzoli International Publishers; Lewes, East Sussex: Produced by Ivy Press. Call no.: 726.51 MAC ↩