Chaplin in Singapore

One of history’s greatest comic actors, Charlie Chaplin, stops over in Singapore in 1932 and makes a return visit in 1936. Raphaël Millet traces these journeys.

Portrait of Charles Chaplin as the Tramp, with his signature bowler hat, large shoes, flexible cane and "toothbrush" moustache, 1915. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of Charles Chaplin as the Tramp, with his signature bowler hat, large shoes, flexible cane and "toothbrush" moustache, 1915. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.Charles Spencer Chaplin (1889–1977), or more famously Charlie Chaplin, was one of the most celebrated stars of the 20th-century silent film era. Born in London on 16 April 1889 to struggling showbiz parents, Chaplin made his foray on stage as a teenager in England, before moving to the US in the early 1910s where he signed on with the Keystone Film Company.

Chaplin is perhaps best known for his iconic screen persona as the Tramp, with his signature bowler hat, cane and “toothbrush” moustache. The penniless pint-sized Tramp, with his bumbling ways and heart-of-gold, would become a hit with film audiences all over the world, always playing the underdog who would triumph in the end.

In all, Chaplin acted in, produced or directed 82 films throughout a glittering screen career spanning nearly 65 years. The multi-talented Chaplin took creative control of most of his films, even writing his own scripts and music scores.

Chaplin Visits Singapore in 1932

Chaplin was 43 years old when he made his first visit to Singapore in 1932 with his half-brother Sydney Chaplin. He was already a rich and famous Hollywood personality, having churned out a string of successful films and founded the film distribution company United Artists. He was feted by fans and the media everywhere he went, and was single again – his second marriage to the American actress Lita Grey had ended in divorce in 1927.

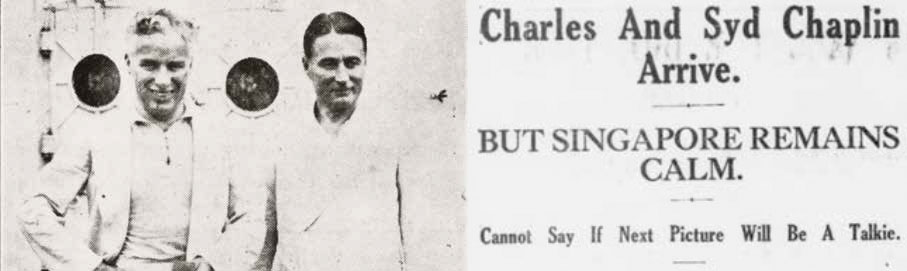

Charles Chaplin (left) and his brother Sydney Chaplin arrived in Singapore on the Suwa Maru on 27 March 1932, and were greeted by a 200-strong crowd at Johnston’s Pier. This was Charles Chaplin’s first visit to Singapore. The Straits Times, 28 March 1932, pp. 11, 12.

Charles Chaplin (left) and his brother Sydney Chaplin arrived in Singapore on the Suwa Maru on 27 March 1932, and were greeted by a 200-strong crowd at Johnston’s Pier. This was Charles Chaplin’s first visit to Singapore. The Straits Times, 28 March 1932, pp. 11, 12.In all Chaplin visited Singapore on three occasions. His second visit was in 1936 (with his then fiancée Paulette Goddard) and his final visit in 1961 (with his last wife, Oona, and a few of their eight children). Chaplin’s inaugural visit in 1932 was particularly significant: firstly, it took place at a key turning point in his personal life and professional career; secondly, it was his first extended holiday after almost 20 years of non-stop work; and finally, it was his first trip to the Orient – a visit that would leave a lasting impression on him in the years to come.

To be more precise, Chaplin stayed in Singapore twice in 1932. The first time was in late March, on his way to Java and Bali in Indonesia, and the second was on his way back from the archipelago in late April into early May. Even though these may appear to be casual visits by a privileged white tourist taking an extended mid-career break, they left an indelible mark in Chaplin’s memory, so much so that he recounted them in his writings on two separate occasions.

Shortly after Chaplin’s journey to the Orient, he penned a travel memoir titled A Comedian Sees the World, published in five instalments in a women’s lifestyle magazine, Women’s Home Companion, from September 1933 to January 1934.1 The fifth instalment of his work deals extensively with the Asian leg of his trip; it touches upon Singapore before moving to Bali and then Japan.

The second time Chaplin mentions Asia again is some 30 years later when he wrote My Autobiography, published in 1964 by the English publishing house Bodley Head, and then by Penguin Books in 1966.2

What Brought Charlie to Asia?

Towards the end of the 1920s, Chaplin was confronted with both a personal and a professional crisis. On the personal front, he had to cope with a few reversals of fortune due in part to the acrimonious divorce from his second wife, Lita Grey, in 1927. The news of the divorce, with charges of abuse and infidelity levelled against Chaplin, received front-page coverage in the scandal-mongering American press.

Adding to his woes, Chaplin had been under severe pressure from the Internal Revenue Service because of unpaid back taxes.3 On the professional front, he had difficulties transitioning from the era of the silent movies to that of the talkies. He was sceptical of the new technology, and, as a compromise, agreed that his latest film, City Lights, released in early 1931, would feature a music score but no dialogue.

On 13 February 1931, Chaplin sailed to Europe for a publicity tour of City Lights, which took him to England, Germany, Austria, Italy and France. Once the tour was done, Chaplin stayed behind in Europe (mostly in Switzerland and on the French Riviera) as he simply did not feel like going back to Hollywood.4 Finally, in February 1932, as he had already been away from home for exactly a year, Chaplin decided to return to California. However, instead of taking the shorter and faster route across the Atlantic and then to the American continent, he would travel a longer, circuitous route via the Orient, a part of the world that he had always wanted to visit.

Not wanting to travel alone, Chaplin asked his half-brother Sydney, then living in Nice, in the south of France, to accompany him. The two of them had grown up together as impoverished youths in London and had moved to Hollywood, where Sydney (or Syd) intermittently managed his brother’s career in between taking on various acting gigs, before quitting Hollywood for good in the late 1920s.

Accompanying them on the trip was Charles’ personal secretary, Toraichi Kono, a Japanese who had worked for him since 1916. Together, the trio boarded the Japanese NYK (Nippon Yusen Kaisha5) ocean liner called Suwa Maru in the port of Naples, Italy, on 2 March 1932. Sailing via the Suez Canal and Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), they arrived in Singapore on 27 March, according to the local press6 – although the date Friday, 25 March is mentioned in the tour itinerary found in the annex to the reprint of Charles Chaplin’s travel memoir.7

The First Leg of the 1932 Visit

Singapore, then part of the Straits Settlements under the British Governor Sir Cecil Clementi, clearly featured in Chaplin’s imagination as one of those exotic places located “East of Suez”,8 or what was then commonly called “the Orient”, as Chaplin refers to in his writings.9

Leaving Ceylon, Chaplin wrote: “Our next port was Singapore, where we entered the atmosphere of a Chinese willow-pattern plate – banyan trees growing out of the ocean.”10 Indeed, it would have looked like a very green and lush coastline as the Suwa Maru sailed into the harbour via the Strait of Malacca, cruising along the picturesque and undeveloped western coast of Singapore.

Even though this is not clearly documented in either Chaplin’s writings or in newspaper articles of the time, the Suwa Maru most likely sailed past the Telok Ayer Basin along the southern shoreline and docked near Johnston’s Pier, located right opposite Battery Road. The pier, which was built in 1856, would be torn down when Clifford Pier, a short distance away along Collyer Quay, was completed in June 1933. Chaplin later recollected: “Myriads of sailboats listed in the bay, and white ocean liners lay dormant, waiting to be fed with cargo, and the harbor sang with color and tropical life.”11 Writing was obviously another one of Chaplin’s many talents.

At Johnston’s Pier, about 200 people waited to greet the Chaplin brothers. This was certainly a change from the heaving crowds that had welcomed Charles Chaplin elsewhere. Relieved at the relatively subdued reception in Singapore – what he was looking for in this trip to the Orient was to escape the usual mob frenzy – he later wrote: “The crowds were not as demonstrative here as they were in Ceylon, but then Singapore is two degrees off the equator and I don’t blame them. Nevertheless, there was a medium crowd and I was cheered, photographed, and interviewed.”12

Interestingly, a journalist sent by The Straits Times to cover the event took it upon himself to explain in his article the reason for the modest size of the welcoming party in Singapore:

“Asiatics are not as demonstrative. They are not in the habit of mobbing cinema stars, even when the star is none other than Charles Chaplin, whose name is better known than that of any other man in the world, whose pictures are as familiar in China, Japan and India as they are in England. Singapore’s cinemagoers did not turn out in force to greet Chaplin, they know of him, they crowd the cinemas to see his pictures, but they did not seem particularly interested in seeing him in the flesh.”13

While still onboard the Suwa Maru, Chaplin agreed to give a group interview to all the journalists present, among whom were British, Japanese, Chinese and Malay reporters, many eager to know if he was still going to make pictures, and if his next picture would be a talkie. To which Chaplin nonchalantly replied: “Of course, I am going to make more pictures. Will my next be silent or talkie? That I cannot say.”

The journalists told him that his latest film, City Lights, had already been shown in Singapore and was very well received by local audiences. Chaplin expressed surprise:

“Is that really so? I should never have believed it. And they liked City Lights, you say? I am glad to hear that. You see, a picture with just a musical accompaniment can be shown anywhere. This is the beauty of it. There are no barriers to the silent picture.”

Once ashore, the brothers were taken on a guided tour of Singapore. Chaplin’s first impression was positive:

“My first view of the city surprised me. Perhaps my imagination was influenced by the lurid portrayals of Hollywood’s conception of it, with its narrow evil streets and sinister droves on every corner. But on coming into the harbor, I found green open spaces and gardens before palatial granite buildings.”14

His brother Syd seems to have been far less enamoured with Singapore than Charles was. In his travel notes peppered with humorous details and unexpected anecdotes, Syd describes a visit to a Hindu temple where they were shown a “golden horse with… [a] swinging and detachable phallus”. He quipped in his usual sarcastic fashion that Singapore “should be called Stinkapore”,15 alluding to the city’s poor sanitary conditions. This was likely observed during their visit to the “native quarters”, presumably the poorer sections of the city.

In fact, it was Charles who had insisted on seeing the less touristy side of Singapore. As an actor and film director, he was always interested in scratching below the surface. Syd highlighted this anecdote about his brother in a subsequent interview with the local press:

“Charlie always makes for the native quarter more than anything else. When he arrives at a place, the faster he gets away from the European part of it, the better. He likes to see how the natives live. If the guide wishes to show him Government House or the Botanical Gardens, he asks for the slums.”16

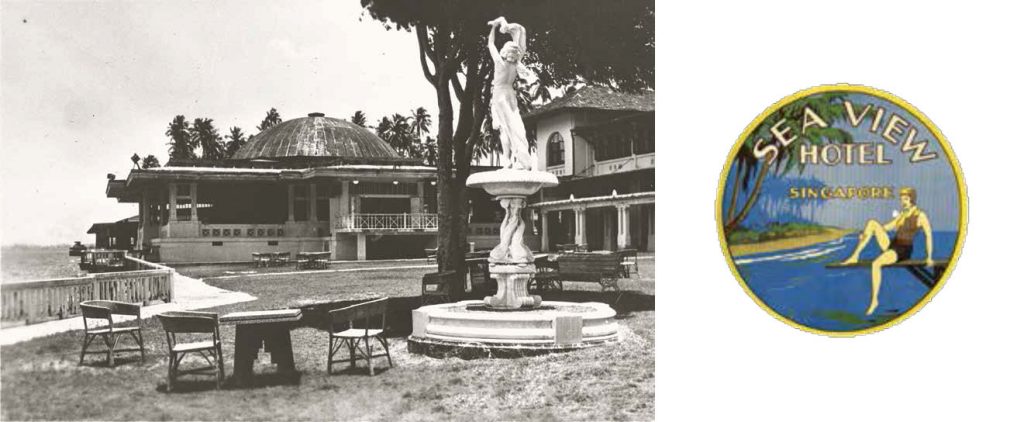

According to Syd’s travel notes, they made the mandatory stop at the Raffles Hotel and then, unexpectedly, drove to the Sea View Hotel in Tanjong Katong “only a short distance from town” and where “every room [came] with a bath, modern sanitation [and] running hot and cold water”. The now-demolished hotel faced the sea (as its name suggested) and was surrounded by a coconut grove. Together with the Adelphi and the Raffles, the Sea View was regarded as one of the finest lodgings on the island and, of the three, “the most beautifully situated of all Singapore’s hotels”.17

(Left) Established in 1906, Sea View Hotel was situated in a grove of coconut trees near the sea at Tanjong Katong, c.1930s. Charles Chaplin and his brother Sydney Chaplin stayed for a night at the hotel on 27 March 1932. Lim Kheng Chye Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

(Left) Established in 1906, Sea View Hotel was situated in a grove of coconut trees near the sea at Tanjong Katong, c.1930s. Charles Chaplin and his brother Sydney Chaplin stayed for a night at the hotel on 27 March 1932. Lim Kheng Chye Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.(Right) Ephemera from the Sea View Hotel.

Unfortunately, the Chaplin brothers were “the only customers”, Syd noted. Although not officially documented, it is very likely that the brothers spent the night at the Sea View Hotel while waiting for their boat to Java. Syd wrote of the Sea View Hotel in yet another humorous note that seem to corroborate the fact of their stay: “They switch off all our lights after serving us with drinks, because it is midnight – and so, we drink in the dark.”18

The next morning, on 28 March, the Chaplins left Singapore, sailing on the steamship Van Lansberge to Batavia (now Jakarta), then by car to Surabaya where they took another boat to Bali. The itinerary had been prepared by their travel agent, Thomas Cook and Son Ltd, whose Singapore branch was then located at 39 Robinson Road.19

The Second Leg of the 1932 Visit

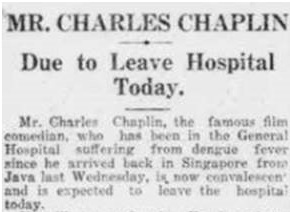

After 18 days in Bali, the Chaplin brothers returned to Singapore via Java, where they disembarked on 20 April 1932. They were not able to catch their connecting ship to Japan on 24 April as they had initially planned as Charles had been stricken with dengue fever during the trip to Bali. On arrival in Singapore, he was immediately taken by ambulance to the Singapore General Hospital, where he was warded for the next eight days.

Not surprisingly, this instantly made the news not only in Singapore, but worldwide. The Associated Press issued a dispatch on 20 April, which was picked up the same day by various newspapers such as the Philadelphia Bulletin, the New York Post, the New York Journal, the Baltimore News, and other leading dailies.20 The Los Angeles Evening Herald Express ran a huge headline on its front page: “Charlie Chaplin Ill in Singapore”, followed by a detailed article that read:

“Charlie Chaplin, American [sic]21 screen actor, was carried ashore to a hospital upon his arrival here from Java today, suffering a mild attack of fever… The screen star’s illness was diagnosed as dengue fever, a disease peculiar to warm climates and in particular to the East and West Indies… Sydney Chaplin, brother of the famous star, who is accompanying him on the tour, told International News Service that Charlie is progressing satisfactorily.”22

In the meantime, Sydney Chaplin stayed at the Adelphi Hotel, where he enjoyed hosting the press, providing journalists with regular updates on Charles’ health, as well as giving The Straits Times an exclusive interview about their recent Balinese experience.23

In the end, Charles Chaplin was warded at the Singapore General Hospital much longer than he had expected. He was discharged on 26 April, thus missing the ship to Japan, and had to stay put in Singapore until 6 May.

Charles Chaplin and his brother made a second stopover in Singapore, arriving on 20 April 1932 via Java. Unfortunately, Chaplin had contracted dengue fever while in Indonesia and was warded at the Singapore General Hospital for eight days. The Straits Times, 26 April 1932, p. 12.

Charles Chaplin and his brother made a second stopover in Singapore, arriving on 20 April 1932 via Java. Unfortunately, Chaplin had contracted dengue fever while in Indonesia and was warded at the Singapore General Hospital for eight days. The Straits Times, 26 April 1932, p. 12.Once Charles was out of the hospital, he joined Syd at the Adelphi Hotel, where they wolfed down fresh pineapples,24 intent on enjoying their remaining days on the island. As Charles describes it in his travel memoir: “There were several days to wait before we could get a boat to Japan, so in the meantime, we merged ourselves into the life of Singapore… Of course anything after Bali is a letdown. But Singapore has its charm.”25

They visited the Singapore zoo as well as the Seiryokan Fishing Pond26 and travelled around the island with drivers provided by the hotel. They also toured the city on rickshaws27 as Charles was very interested in seeing more of the natives’ quarters – much to Syd’s dismay – who, in his travel notes, recalls that a local doctor had told them that “since the forced closing of the red light district, girls now solicit [for business] from rickshaws”, contributing to a rise in the number of local men afflicted with venereal diseases.28

With so much time on their hands, the Chaplin brothers were thrust into Singapore’s social life, which they took to like ducks to water. On one occasion, they were entertained by the Ranee of Sarawak. They also met with Joe and Julius S. Fisher, two South African brothers who had settled in Singapore in the late 1910s and made their fortune in the film industry. Joe Fisher was the managing director of Capitol Theatres Ltd, while Julius was its publicity manager.

Charles Chaplin (4th from the left) was entertained by the Ranee of Sarawak, her daughter H. H. Daya Elizabeth and Mr H. C. Strickland on 27 April 1932. Courtesy of Roy Export Company Establishment.

Charles Chaplin (4th from the left) was entertained by the Ranee of Sarawak, her daughter H. H. Daya Elizabeth and Mr H. C. Strickland on 27 April 1932. Courtesy of Roy Export Company Establishment.The Fishers took Charles and Syd on a tour of Capitol Theatre, which had been built a year earlier at the corner of Stamford and North Bridge roads. The Capitol was a grand building that was designed in the neoclassical style. It was one of the finest cinemas of the era, with plush seating for 1,600 patrons, including circle seats, and exceptional acoustics.

The Fishers also took the Chaplin brothers to see the horse races in Serangoon on 30 April, which was duly reported by The Straits Times the next day. The headline read “Chaplin Bros. at the Races”, with a photograph of them dressed smartly in white linen suits and pith helmets that they had purchased a few weeks earlier in Cairo.

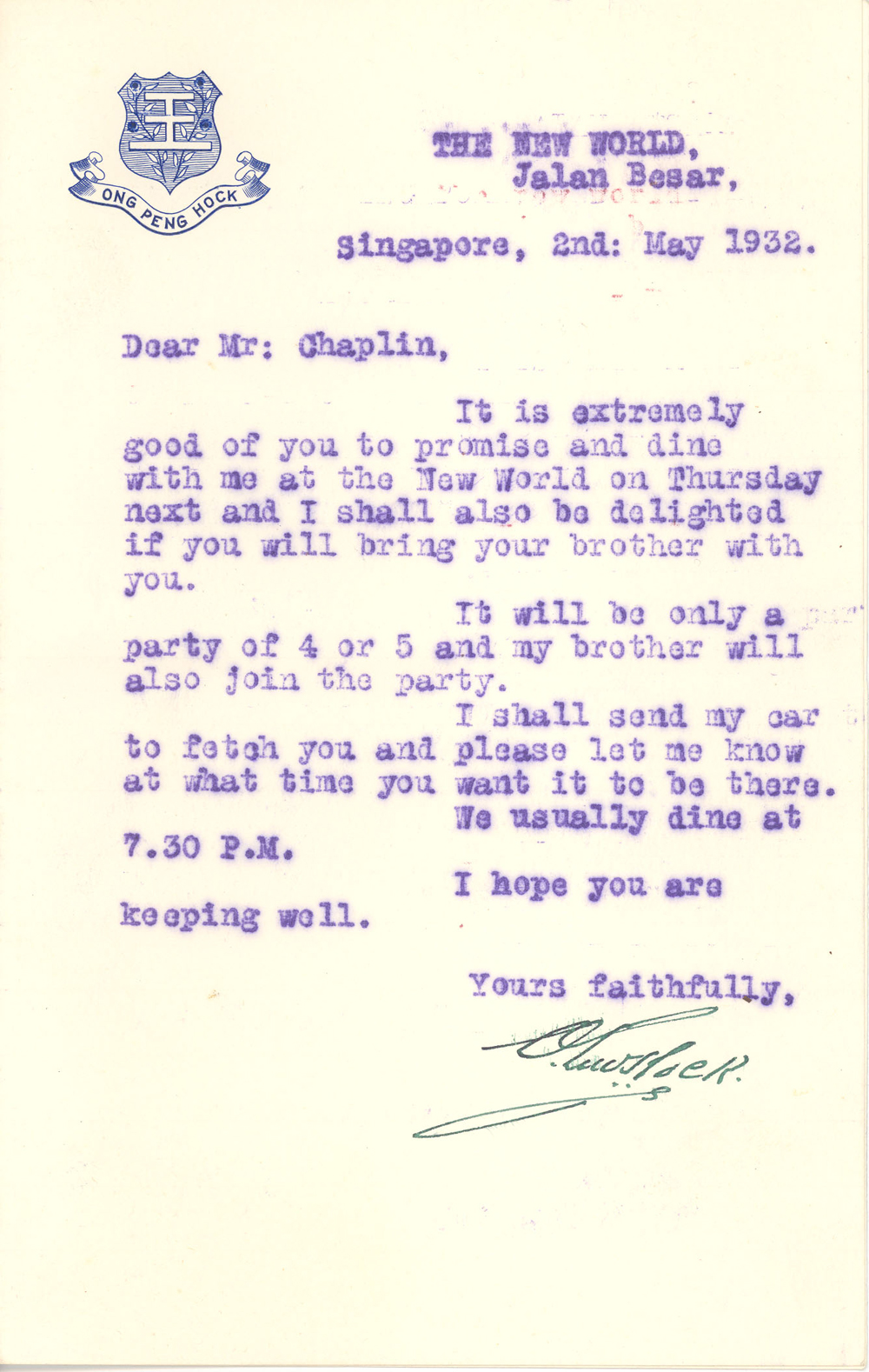

On 2 May, Charles Chaplin received a letter from the local tycoon Ong Peng Hock, who invited him and Syd for dinner on the following Thursday at the New World amusement park (which Ong and his elder brother Boon Tat owned) in Jalan Besar. The Chaplins were treated to “an elaborate Chinese dinner”29 by Ong, who then introduced them to Chinese and Malay actors and performers working at the New World.

Charles enjoyed New World so much that he returned with Syd on several occasions before their departure: “Occasionally we would go to the New World – the native Coney Island of Singapore – where every known variety of entertainment is given, from Malay opera to prizefighting.” One evening, after watching a boxing match at New World, Charles was asked to enter the ring and give the prize to the winner.30 But what truly fascinated him was the variety of local theatre.

Letter from tycoon Ong Peng Hock inviting Charles Chaplin and his brother Sydney Chaplin for dinner at the New World amusement park. Courtesy of Charlie Chaplin Archive.

Letter from tycoon Ong Peng Hock inviting Charles Chaplin and his brother Sydney Chaplin for dinner at the New World amusement park. Courtesy of Charlie Chaplin Archive.“The Chinese drama listed several nights. My brother and I would sit of an evening trying to guess the different symbols that the actors used during the play. One was a stick with a fringe of wool around the top and center, which the actors would shake majestically. I guessed correctly. It was a horse.”31

As someone who made his mark in Hollywood, the mecca of the entertainment industry, but who also was, at the same time, an actor and artist very much drawn to talent, Charles Chaplin could appreciate the variety of entertainment that New World offered, recalling it as one of the highlights of his stay on the island:

“My outstanding memory of Singapore is of Chinese actors who performed at the New World Amusement Park, children who were extraordinarily gifted and well read, for their plays consisted of many Chinese classics by the great Chinese poets… The play I saw lasted three nights… Sometimes it is better not to understand the language, for nothing could have affected me more poignantly than the last act, the ironic tones of music, the whining strings, the thundering clash of gongs and the piercing, husky voice of the banished young prince crying out in the anguish of a lost soul… as he made his final exit.”32

On 6 May 1932, after an extended 15-day sojourn in Singapore, the Chaplin brothers departed Singapore for Japan on the NYK vessel Terukuni Maru. They would both come back to visit Singapore again, but not together: Charles in 1936 and 1961; and Sydney in 1937.

Chaplin Returns to Singapore in 1936

Almost exactly four years later, soon after Charles Chaplin’s latest film Modern Times was completed and released, he made his second trip to Singapore.

Charles Chaplin’s silent film Modern Times premiered at the Capitol Theatre on 12 May 1936, barely a month after Chaplin left Singapore. The Morning Tribune, 21 April 1936, p. 20.

Charles Chaplin’s silent film Modern Times premiered at the Capitol Theatre on 12 May 1936, barely a month after Chaplin left Singapore. The Morning Tribune, 21 April 1936, p. 20.Modern Times would be the last film in which the affable Tramp, Chaplin’s universally recognised screen persona, would appear. Produced in the middle of the decade-long Great Depression and capturing the angst of the period, Modern Times is a tragicomedy depicting, among other themes, the struggles of work life in the era of rising industrial automation.

Chaplin was accompanied on his second visit to Asia by his new fiancée and favourite leading lady, the glamorous Paulette Goddard (1910−1990), who was cast as his co-star and love interest in Modern Times.

Film still from Modern Times. This was the last film in which the affable Tramp, Chaplin’s now universally recognised screen persona, would appear. Produced during the Great Depression years, the film depicts the struggles of work life in the era of rising industrial automation. Courtesy of Modern Times © Roy Export S.A.S.

Film still from Modern Times. This was the last film in which the affable Tramp, Chaplin’s now universally recognised screen persona, would appear. Produced during the Great Depression years, the film depicts the struggles of work life in the era of rising industrial automation. Courtesy of Modern Times © Roy Export S.A.S.Travelling with them was Paulette’s mother, Alta Mae Goddard, acting as a chaperone, and Chaplin’s new secretary-cum-valet, Frank Yonemori. Sailing via Yokohama, Shanghai, Canton and Hong Kong, the party arrived in Singapore on the Suwa Maru – the same ship that had brought Chaplin to Singapore in 1932 – on 18 March 1936.

This time, sailing from the East across the South China Sea, the Suwa Maru docked at Clifford Pier, which had been built in 1933. Even before their arrival, there had been much speculation about Chaplin’s and Goddard’s rumoured wedding (this would have been Chaplin’s third marriage), which was said to have taken place either in Shanghai or Canton, or perhaps soon to be solemnised in Singapore. On 16 March 1936, The Malaya Tribune reported in an attention-grabbing headline that “Charlie Chaplin May Be Married in Singapore”; a few days later on 19 March, the front-page headline in The Singapore Free Press read “Chaplin Mysterious About Marriage”. 33

Charles Chaplin flanked by Alta Mae Goddard (left) and Paulette Goddard on their arrival in Singapore on the Suwa Maru on 18 March 1936. The Singapore Free Press, 19 March 1936, p. 1.

Charles Chaplin flanked by Alta Mae Goddard (left) and Paulette Goddard on their arrival in Singapore on the Suwa Maru on 18 March 1936. The Singapore Free Press, 19 March 1936, p. 1.Before disembarking, the celebrity couple were greeted on board by Julius S. Fisher, the publicity manager of Capitol Theatres Ltd, whom Charles had met on his first visit here in 1932. Once again, Chaplin’s arrival did not go unnoticed by the local press, but this time the crowds were much larger compared with his first visit. The Singapore Free Press reported on 19 March:

“Although the Suwa Maru arrived earlier than was expected, there was a large crowd at the wharf to see Mr. Chaplin. Miss Goddard, who has a trim figure and vivacious personality to go with her pretty face, and Mr. Chaplin, who was dressed in his usual faultless style, were at the rails when the ship berthed. Mr. Chaplin was given a rousing reception. A Malay police corporal, who had been limiting the numbers of sightseers wanting to go aboard, saluted Mr. Chaplin as he stepped from the gangway. Mr. Chaplin held out his hand to the Malay corporal, who shook it heartily. The corporal was so pleased at Mr. Chaplin’s friendly gesture that he gripped Mr. Chaplin’s hand in both his own hands. As if in recognition of Mr Chaplin’s democratic spirit, a Chinese coolie led a cheer and hand-clap, in which all the wharf labourers, hawkers and money-changers joined. Mr Chaplin removed his white felt hat from his whitening hair to acknowledge the coolies’ cheer. The taxi syces also clapped their hands as Mr. Chaplin, Miss Goddard and Mrs. Goddard drove away.”34

The party took their rooms on the top floor of the Coleman Street wing of the Adelphi Hotel, and the press made sure to mention that “Miss Goddard and her mother are occupying the same room”.35 That same night, they dined in Katong and spent the evening at the New World amusement park, which Chaplin wanted Goddard to experience, before returning to the Adelphi slightly before midnight.

Adelphi Hotel at the junction of Coleman Street and North Bridge Road, c.1945. Charles Chaplin and his brother Sydney Chaplin stayed at the hotel in April 1932. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

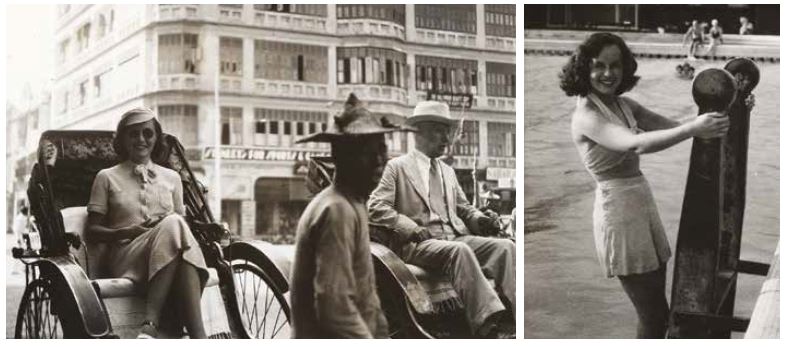

Adelphi Hotel at the junction of Coleman Street and North Bridge Road, c.1945. Charles Chaplin and his brother Sydney Chaplin stayed at the hotel in April 1932. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.The following morning, 19 March, Chaplin and Goddard toured the city by rickshaw. “Paulette was fascinated with the rickshas. As her puller carried her a few paces, she cried out excitedly to Charlie, who laughed back a reply,” The Singapore Free Press gleefully reported on 20 March.36 Lunch would take place at the Tiffin Room of the Raffles Hotel with Julius S. Fisher and his brother Joe, the managing director of Capitol Theatres Ltd. Both were excited to host the couple as Modern Times was scheduled to open at the Capitol Theatre on 12 May 1936.37

From the left: Charles Chaplin, Julius S. Fisher, Sydney Chaplin and Joe Fisher. Brothers Joe and Julius Fisher were South Africans who settled in Singapore in the late 1910s and later made their fortune in the movie industry. Joe was the managing director of Capitol Theatres Ltd, while Julius was the publicity manager. Courtesy of Roy Export Company Establishment.

From the left: Charles Chaplin, Julius S. Fisher, Sydney Chaplin and Joe Fisher. Brothers Joe and Julius Fisher were South Africans who settled in Singapore in the late 1910s and later made their fortune in the movie industry. Joe was the managing director of Capitol Theatres Ltd, while Julius was the publicity manager. Courtesy of Roy Export Company Establishment.Interestingly, on 20 March, Chaplin was invited to visit the Singapore Reformatory by its Superintendent F. C. Johnson (whom he had met four years previously at New World). Chaplin readily obliged as he was very interested in social issues. Interacting with the homeless boys was a reminder of his own childhood fraught with poverty and hardship.

Over the next few days, Chaplin and Goddard visited various places of interest in Singapore, such as the Singapore Swimming Club, the Botanic Gardens and the Seiryokan Fishing Pond. Needless to say, the local press trailed the celebrity couple wherever they went, with Goddard always impeccably turned out in the latest fashions and looking every inch the glamorous star that she was. These outings provided ample fodder for press photographers.

(Left) Charles Chaplin and Paulette Goddard enjoying a rickshaw ride through the streets of Singapore on 19 March 1936. Courtesy of Roy Export Company Establishment.

(Left) Charles Chaplin and Paulette Goddard enjoying a rickshaw ride through the streets of Singapore on 19 March 1936. Courtesy of Roy Export Company Establishment.Although Chaplin’s marriage to Goddard would last only six years, she was regarded as a fine match for him as she was “strong willed, independent [and] a lover of life”.38 Goddard acted in another of Chaplin’s film – in fact his first talkie – in 1940, entitled The Great Dictator, and enjoyed a hugely successful film career right into the 1970s.

On 24 March, Chaplin and his party left from Seletar airport on a Qantas Airways flight39 bound for Batavia,40 to begin their tour of the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia). Returning from Bali via Batavia (“by Dutch plane”, meaning on a KNILM flight41), they landed in Singapore on 7 April 1936.42 Interviewed by a Morning Tribune reporter, Chaplin declared: “I have made no special plans for my stay in Singapore, and I will just take things as they come.”43

The three-night stopover was mostly uneventful save for another lunch meeting with the Fisher brothers, this time joined by two members from Asian royal families. One was a son of the Siamese King Chulalongkorn, Prince Purachatra Jayakara (who would unfortunately pass away a few months later, in September 1936), and the other was Tunku Ismail, the Crown Prince of Johor (who would be crowned as Sultan Ismail in 1960).

On Friday 10 April, Chaplin and Goddard finally sailed from Singapore on the French liner Aramis, heading for Indochina before taking a slow cruise back to the US. Chaplin’s fascination with Singapore was not over yet. He would return again in 1961 with his fourth (and final) wife, the actress Oona O’Neil, whom he married in 1943. But that, as they say, is another story.

Raphaël Millet is a film director, producer and critic with a passion for early cinema. He has published two books, Le Cinéma de Singapour (2004) and Singapore Cinema (2006), as well as directed documentaries such as Gaston Méliès and His Wandering Star Film Company (2015), screened as part of the 2015 Singapore International Film Festival, and Chaplin in Bali (2017), which opened the Bali International Film Festival in 2017.

Raphaël Millet is a film director, producer and critic with a passion for early cinema. He has published two books, Le Cinéma de Singapour (2004) and Singapore Cinema (2006), as well as directed documentaries such as Gaston Méliès and His Wandering Star Film Company (2015), screened as part of the 2015 Singapore International Film Festival, and Chaplin in Bali (2017), which opened the Bali International Film Festival in 2017.

NOTES

-

Chaplin, C. (2014). A comedian sees the world (Parts IV & V). L. S. Haven (Ed.). Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Chaplin, C. (2003). Charles Chaplin: My autobiography (Chapter 23). London: Penguin Classics. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Haven, L.S. (2014). Introduction (p. 2). In C. Chaplin, A comedian sees the world. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Chaplin, 2003, p. 361. ↩

-

The Japan Mail Steam Ship Company. ↩

-

Charles and Syd Chaplin arrive. (1932, March 28). The Straits Times, p. 12; Charlie Chaplin in Singapore. (1932, April 2). The Malayan Saturday Post, p. 29. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Haven, L.S. (2014). Tour itinerary (p. 149). In C. Chaplin, A comedian sees the world. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

An expression popularised by Rudyard Kipling in his 1890 poem titled “Mandalay”, frequently used in the 1920s and 30s, particularly in guide books such as Willis, A.C. (1934). Willis’s Singapore guide. Singapore: Advertising and Publicity Bureau Ltd. (Call no.: RRARE 915.957 WIL; Microfilm no.: NL 30538) ↩

-

Chaplin, 2003, p. 362. ↩

-

Chaplin, 2003, p. 362. ↩

-

Chaplin, 2014, p. 127. ↩

-

Chaplin, 2014, p. 127. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 28 Mar 1932, p. 12. ↩

-

Chaplin, 2014, p. 127. ↩

-

Sydney Chaplin, 1932 travel notes, Charlie Chaplin Archive. ↩

-

The Chaplins’ plans for the future. (1932, April 24). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Willis, A.C. (1936). Willis’s Singapore guide (pp. 30–31). Singapore: Alfred Charles Willis. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Sydney Chaplin, 1932 travel notes, Charlie Chaplin Archive. ↩

-

A copy of the Chaplins’ itinerary to Java and Bali drawn up by Thomas Cook and Son has been preserved in the Charlie Chaplin Archive. ↩

-

Clippings of these articles about Charles Chaplin’s illness in Singapore are kept at the Charlie Chaplin Archive. ↩

-

Charles Chaplin was born in the United Kingdom. He never became an American citizen, and always retained British citizenship. ↩

-

Charlie Chaplin ill in Singapore. (1932, April 20). Los Angeles Evening Herald Express, p. 1. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 24 Apr 1932, p. 9. ↩

-

Cf. Sydney Chaplin’s travel notes: “They insist upon serving us California canned fruits instead of the delicious fresh fruits of Singapore. What a strange form of snobbishness! Charlie and I prefer gorging ourselves with fresh pineapples!” ↩

-

Chaplin, 2014, p. 139. ↩

-

Seiryokan Fishing Pond. (n.d.). Retrieved from Charlie Chaplin Picture Database. [Note: The author was unable to find references to such a pond in primary sources of Singapore.] ↩

-

Sydney Chaplin’s notes: “We take rikishaw [sic] rides every night through native quarters” ↩

-

Sydney Chaplin, 1932 travel notes, Charlie Chaplin Archive. ↩

-

Sydney Chaplin, 1932 travel notes, Charlie Chaplin Archive. ↩

-

Gunboat Jack stops Guillermo. (1932, May 2). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 16. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Chaplin, 2014, p. 139. ↩

-

Chaplin, 2003, pp. 362–363. ↩

-

Charlie Chaplin may be married in Singapore. (1936, March 16). The Malaya Tribune, p. 11; Chaplin mysterious about marriage. (1936, March 19). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Rumor of Chaplin wedding in Singapore. (1936, March 18). Barrier Miner, p. 2.Retrieved from Trove website. [Note: Although both Charles and Paulette remained extremely discreet about their wedding, it seems that they married offshore near Canton, something which Chaplin himself later acknowledged in his autobiography: “During this rip Paulette and I were married”, also adding a few pages later that they divorced six years later in June 1942 in Juarez, Mexico.] ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 19 Mar 1936, p. 1. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 19 Mar 1936, p. 1. ↩

-

Paulette’s first rickshaw ride. (1936, March 20). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Page 20 advertisement column 1. (1936, April 21). The Morning Tribune, p. 20. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Gamine: Paulette Goddard. (n.d.). Retrieved from The Chaplin Office website. ↩

-

Untitled. (1936, March 24). The Malaya Tribune, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Qantas, founded in 1920 as the Queensland and Northern Territory Aerial Services, had started flying internationally from May 1935, when the service from Darwin was extended to Singapore. When Chaplin took this flight, this was still a fairly new route. ↩

-

The Koninklijke Nederlandsch-Indische Luchtvaart Maatschappij (known in English as the Royal Netherlands Indian Airways), founded in 1928, had in 1936 launched a weekly flight from Batavia to Singapore via Palembang. The airline ceased operations in 1947. ↩

-

Chaplin’s return. (1936, April 5). The Straits Times, p. 1; Chaplin Chaplin back in Singapore. (1936, April 8). The Morning Tribune, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Morning Tribune, 8 Apr 1936, p. 11. ↩