The Doctor Turned Diplomat: John Crawfurd’s Writings on the Malay Peninsula

John Crawfurd, the 19th-century British colonial administrator, was known for his insightful writings on ethnology and history in the Malay Peninsula. Wilbert Wong examines the ideas of this visionary scholar and thinker.

Portrait of John Crawfurd, 1857. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

Portrait of John Crawfurd, 1857. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.The National Library, Singapore, has in its collection a number of items relating to John Crawfurd’s writings on Asia. In 2016, the collection was further enriched by an acquisition from Dr John Bastin – a noted authority on Stamford Raffles and author of numerous books and articles on the history of Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia.

Among the 19th-century British scholar-administrators of the Malay Peninsula, Crawfurd (1783–1868) was one of the most accomplished. He was highly regarded by the scholarly community for his formidable intellect and contributions to the field of ethnology, linguistics and Asian subjects – especially on Southeast Asia.

The Spectator newspaper noted in 1834 that “Crawfurd [was] well known by his writings on Eastern manners and statistics, and his exertions to open the British trade with China and India”.1

Crawfurd’s writings on Southeast Asia provided a wealth of information for those with a keen interest in the region, especially merchants, intellectuals, and aspiring imperial civil servants and officials. His body of scholarly work, however flawed and imperfect it may seem from a contemporary perspective, is a major contribution to our understanding of the socio-political and cultural milieu of colonial Malaya.

Colonial sources invariably provide the only means of historical information on Malaya in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Like many of his contemporaries, such as the British Orientalist and linguist, William Marsden (1754–1836), and Stamford Raffles (1781–1826), Crawfurd sought to understand the interplay between mankind and its history, and the inhabitants of the Malay Peninsula often featured in his writings on ethnology and world history. The knowledge gained from his experiences and observations on the region would eventually be used to fuel his scientific debates on ethnology – in other words, the study of societies, cultures and the nature of mankind.

Crawfurd’s Early Life and Career

Crawfurd was born on 13 August 1783 on the island of Islay in Scotland.2 He was the son of Samuel Crawfurd, a physician and a “man of sense and prudence”, and Margaret Campbell.3 Crawfurd was educated in a village school in Bowmore, Islay. In 1799, he enrolled in medical school in Edinburgh; medicine was a field for which, according to his 1868 obituary in The Sydney Morning Herald, he “never had much taste, having been chosen for him” – presumably by his father.4 It later became evident that young Crawfurd’s interest lay in languages, history, ethnology, natural sciences and political administration.

After completing his medical studies in 1803, Crawfurd left for Calcutta, India, as an assistant surgeon in the East India Company’s Bengal medical service, where he was assigned to the army.5 In 1808, on completion of five years of active service in the northwestern provinces of British India, Crawfurd was appointed to the medical service at Prince of Wales Island, present-day Penang. Never one to sit on his laurels, Crawfurd used his time there to study the Malay language and its people.6

In 1811, Crawfurd, together with Raffles and another Scottish intellectual John Leyden (1775–1811), was invited by Lord Minto (1751–1814), then Governor-General of India, to accompany him on a military expedition against the Dutch in Java.7 This marked a major turning point in Crawfurd’s career; he would become, as the anthropologist Ter Ellingson wrote in his book, The Myth of the Noble Savage, “a doctor-turned-colonial-diplomat”.8

Crawfurd held various senior administrative posts during the brief British occupation of Java between 1811 and 1816 due to his command of the Malay language, including an appointment as Resident at the royal court of the Sultan of Yogyakarta. He befriended the Javanese aristocratic literati and studied both Kawi, an ancient form of Javanese as well as contemporary Javanese.

On his return to Britain in 1817, Crawfurd became a fellow of the Royal Society. His position and local connections in the Malay Peninsula and Java enabled him to acquire a decent collection of local manuscripts. Putting together the information he had gathered during his sojourn in Southeast Asia, Crawfurd published his widely acclaimed three-volume History of the Indian Archipelago in 1820.9 This seminal work, according to a review in The Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia in 1856, placed him among “the first rank of ethnographers”.10

In 1821, Crawfurd left England again for India; this time he was assigned to head a mission to Siam (now Thailand) and Cochin China (Vietnam), with the chief objective of opening up these countries to trade. However, he failed because of regional tensions and suspicions raised among the local authorities there.11

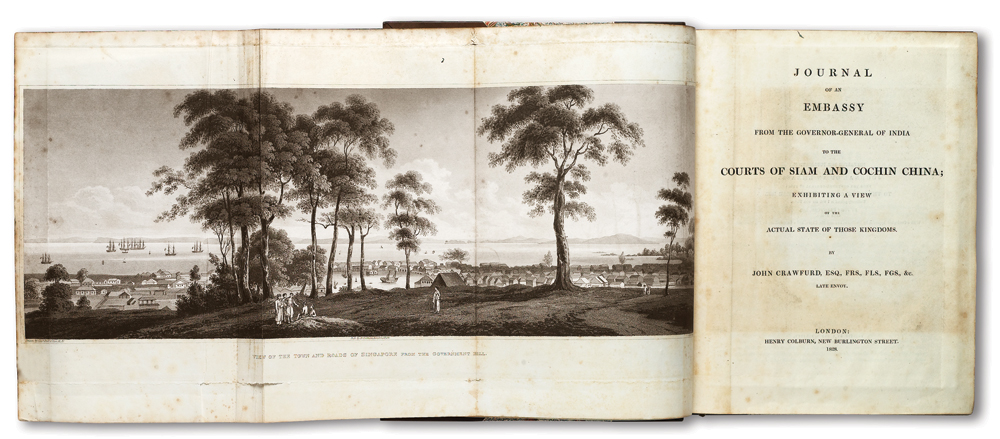

Journal of an Embassy from the Governor-General of India to the Courts of Siam and Cochin China is a record of John Crawfurd’s commercial and diplomatic mission to the courts of Siam and Cochin China from 1821–22. The frontispiece shows a black-and-white version of the painting titled “A View of the Town and Roads of Singapore from the Government Hill” by Captain Robert James Elliot. All rights reserved, Crawfurd, J. (1828). Journal of an Embassy from the Governor-General of India to the Courts of Siam and Cochin China: Exhibiting a View of the Actual State of Those Kingdoms. London: Henry Colburn.

Journal of an Embassy from the Governor-General of India to the Courts of Siam and Cochin China is a record of John Crawfurd’s commercial and diplomatic mission to the courts of Siam and Cochin China from 1821–22. The frontispiece shows a black-and-white version of the painting titled “A View of the Town and Roads of Singapore from the Government Hill” by Captain Robert James Elliot. All rights reserved, Crawfurd, J. (1828). Journal of an Embassy from the Governor-General of India to the Courts of Siam and Cochin China: Exhibiting a View of the Actual State of Those Kingdoms. London: Henry Colburn.Crawfurd’s Achievements in Singapore

On 9 June 1823, Crawfurd succeeded William Farquhar as the second Resident of Singapore – Crawfurd had first visited the island in 1822 enroute from India to Siam – and remained in office until 1826. It was during this period that Crawfurd made his biggest political achievement: he was instrumental in the proposal and negotiation of the Treaty of Friendship and Alliance on 2 August 1824, which saw Singapore being effectively ceded by its rulers, Sultan Hussein Shah and Temenggong Abdul Rahman, to the British East India Company.

Singapore flourished under Crawfurd’s administration, which was marked by rapid growth in trade, population and revenue. Remarkably, by 1826, Singapore’s revenue had outstripped that of Penang. Given his administrative accomplishments, historian C. M. Turnbull may be justified in praising Crawfurd as one of the three outstanding pioneer administrators of Singapore, after Raffles and William Farquhar (see text box below).12

Crawfurd continued to play an active role in the British East India Company on completion of his tenure as Resident of Singapore in 1826, undertaking diplomatic assignments in Burma (now Myanmar), before retiring permanently to England in 1827.13 Although Crawfurd left the region for good, he continued to take a keen interest in matters concerning the Far East until the end of his life, becoming the first president of the London-based Straits Settlements Association on 31 January 1868.14 Crawfurd passed away on 11 May 1868 at his residence in South Kensington, London, at the age of 85, leaving behind a son and two daughters.15

The Malay Peninsula in Crawfurd’s Writings

An examination of Crawfurd’s obituaries would give the impression that his literary fame continued to rise after he ended his career in Asia, to the extent that it seemed to have outshone his civil service accomplishments in the Far East.16 In spite of several unsuccessful attempts to enter British politics, he continued making headlines in the intellectual world by producing notable publications such as A Grammar and Dictionary of the Malay Language with A Preliminary Dissertation (1852)17 and A Descriptive Dictionary of the Indian Islands & Adjacent Countries (1856)18 and through his journal contributions to the scholarly periodical of the Ethnological Society of London – which he led in 1861 as president.19 As a leading ethnographer and expert on Southeast Asia, Crawfurd was well known among prominent intellectuals of the time, and was counted among Charles Darwin’s circle of friends.20

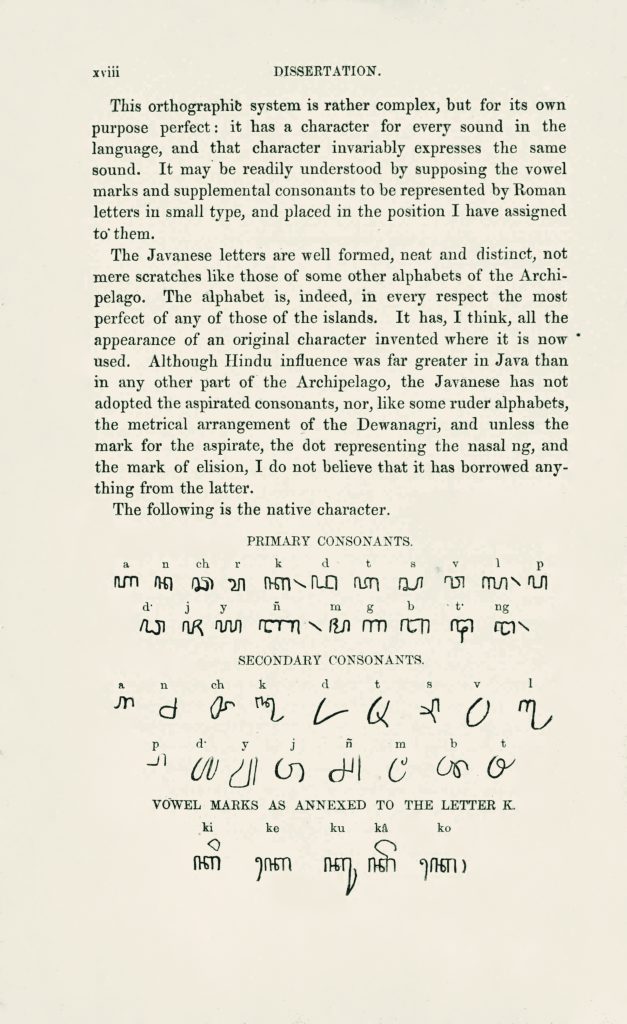

Page xviii of A Grammar and Dictionary of the Malay Language with a Preliminary Dissertation shows the primary consonants, secondary consonants and vowel marks of the letter “K” in Javanese script. All rights reserved, Crawfurd, J. (1852). A Grammar and Dictionary of the Malay Language with a Preliminary Dissertation. London: Smith, Elder, and Co.

Page xviii of A Grammar and Dictionary of the Malay Language with a Preliminary Dissertation shows the primary consonants, secondary consonants and vowel marks of the letter “K” in Javanese script. All rights reserved, Crawfurd, J. (1852). A Grammar and Dictionary of the Malay Language with a Preliminary Dissertation. London: Smith, Elder, and Co.Crawfurd’s publications on the Far East were the result of his extensive journeys and voyages made during his time in the region, where he amassed a diversity of materials on ethnology, natural history, local history, geography and geology.21 As an active participant in the lively 19th-century scientific and philosophical debates on the nature of mankind, he took advantage of his observations in Asia to roundly debunk the idea that offspring produced from the union or “commixture” of two different races would become sterile and incapable of producing healthy children of their own.

In his article in the journal of the Ethnological Society of London, On the Supposed Infecundity of Human Hybrids or Crosses, which was read in 1864 and published in 1865, Crawfurd highlighted the theory that “mongrels resulting from the union of two different races of the human family” were sterile (like a mule – a hybrid between two opposite species of the same genus of lower animals). The idea had “lately sprung up” and was beginning to obtain currency in France and America.22 Crawfurd saw this theory as one that was “without a shadow of foundation”, citing evidence in the mixed-race communities in Asia, “which multiply just as fast as do the parent stocks from which they derived”.23 He would have also drawn this conclusion from his observation of the mixed-race communities in the Malay Peninsula – as suggested in his other ethnological article, On the Commixture of the Races of Man as Affecting the Progress of Civilisation.24 Here, pointing to the Peranakan communities of the Malay Peninsula, Crawfurd wrote:

“The intercourse and settlement are still in progress, and out of it has sprung a cross-breed known, as in the colonising Arabs and Chinese, by the term Páranakan [sic], with the national designation of the father annexed, and literally signifying ‘offspring of the womb’,.…”25

In Malacca, which had been colonised by the Portuguese since 1511, he observed that a cross-race of Eurasians had sprung up, and they had “so much of Malay blood as to be hardly distinguishable from the Malays themselves”.26

Crawfurd’s view that the children of mixed racial unions would become an “intermediate” offspring, superior to the race of the “inferior” parent, but inferior to the race of the “superior” one, would seem somewhat more controversial.27 When discussing the Peranakan communities of the Malay Peninsula, he pointed out that “these half-castes speak the language of the father as well as that of the mother, and are distinguished from the pure Malay by superior intelligence”.28 In History of the Indian Archipelago, Crawfurd found that the Chinese who intermarry “with the natives of the country, generate a race inferior in energy and spirit” to the Chinese.29 He also wrote supportively of mixed-racial unions between Europeans and native inhabitants in European colonies because he saw it as a laudable, if patronising, way of improving the existing indigenous societies.30

In his scientific views, Crawfurd was a believer in polygenesis, a theory that supposes the multiple origins of mankind.31 Mankind, according to the tenets of polygenesis, consists of different races or species that are spread across different geographical locations around the world.32 He opposed Darwinism because of its stand on the common origins of man, considering it to be without firm foundation and not backed by historical or archaeological evidence.33 A recent 2016 study by Gareth Knapman has furthermore revealed that Crawfurd opposed Darwinism because it promoted a hierarchy of races, which Crawfurd, as an advocate of racial equality, was completely against.34

Crawfurd assumed that each race was equally as old as any other, and the reason behind their distribution across the globe was a cosmic mystery “beyond the power of our comprehension”.35 He distinguished each race according to their outer physical appearances, such as the colour of the skin, hair and eyes, average height, hair texture and facial features.36 But in spite of their differences, he argued, they all belonged to the same genus, Homo (modern humans are classified as Homo sapiens), just like the different breeds of dogs, although having different physical features, are all from the same family, Canidae.37

Crawfurd was against using anatomy to distinguish the “species” of mankind, more specifically the classification of races according to the shape of the skull that was being promoted by the anatomist and naturalist Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (1752–1840), with the launch of his publication De Generis humani varietate nativa (On the Natural Variety of Mankind), in 1795. Crawfurd, perhaps also drawing his conclusion from his knowledge of medicine, stressed that regardless of race, one would not be able to tell the difference between the skull of a “Hindu-Chinese” and that of a Malay.38 This was why Crawfurd thought it best to catalogue the different races according to their external physical features, and this was how he would distinguish between the inhabitants of the Indian Archipelago39 and the Malay Peninsula in his studies.

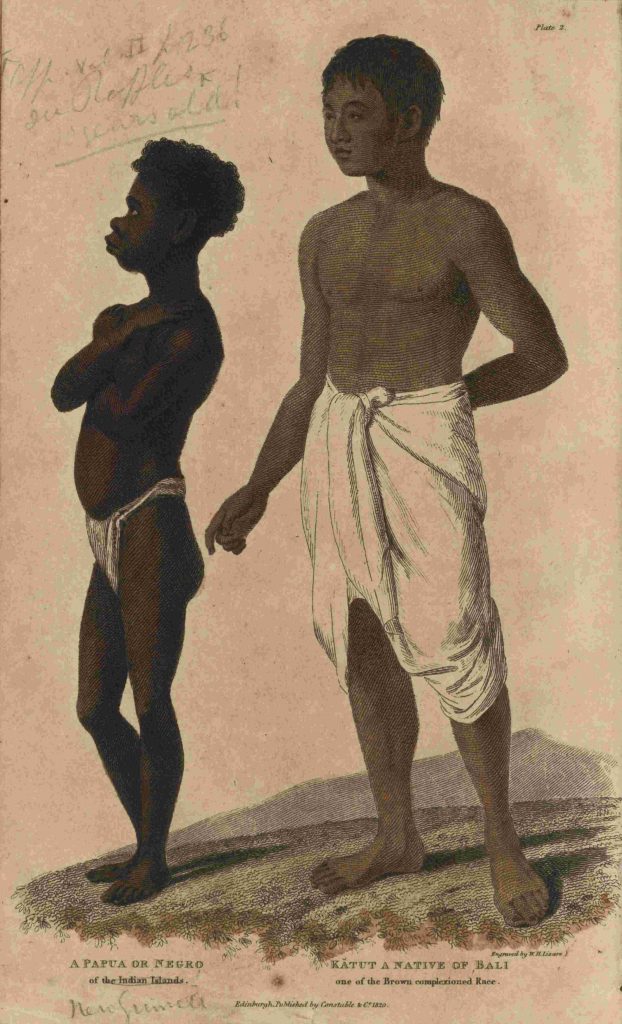

The inhabitants of the Indian Archipelago, in Crawfurd’s observation, consist of many different races, which he divided into three groups based on appearance: the brown-complexioned, straight-haired men, such as the Malays; men of dark complexion with woolly hair, whom Crawfurd termed the “Oriental Negroes” because their features were similar to the “African Negroes” (although Crawfurd believed that the two were not of the same race due to the differences in their physical characteristics and language); and men of brown complexion with frizzled hair, like the inhabitants of Timor.40

A Papua or Negro of the Indian Islands (left) and Katut, a native of Bali (right). All rights reserved, Crawfurd, J. (1820). History of the Indian Archipelago: Containing an Account of the Manners, Arts, Languages, Religions, Institutions, and Commerce of its Inhabitants (Vol. I). Edinburgh: Printed for Archibald Constable and Co.

A Papua or Negro of the Indian Islands (left) and Katut, a native of Bali (right). All rights reserved, Crawfurd, J. (1820). History of the Indian Archipelago: Containing an Account of the Manners, Arts, Languages, Religions, Institutions, and Commerce of its Inhabitants (Vol. I). Edinburgh: Printed for Archibald Constable and Co.The people of the Malay Peninsula consisted of the brown-complexioned Malays and the dark, woolly-haired, “Oriental Negroes”, also known locally as the “Sámang” (Semang) or “Bila”.41 In History of the Indian Archipelago, Crawfurd noted that, besides their appearance, even the language spoken by the Archipelago’s “Oriental Negroes” was distinct from the brown-coloured races of the region, which would mark them out as separate races.42

Crawfurd’s direct examination of the aboriginals of the Malay Peninsula, the Orang Asli, seemed to have been limited to the three Semang people he saw in Penang and Singapore, as well as the few Orang Laut (or “sea gypsies”) he came across, which was understandable since he had never ventured into the interior of Malaya.43 Instead, Crawfurd had to rely on the findings of other Orientalists, such as James Richardson Logan (1819–69) and John Turnbull Thomson (1821–84), when studying the other Aslian tribes.44 Those who possessed Malay-like features – the Jakun for instance – were deemed to belong to the Malay group, which Crawfurd labelled as “uncultivated Malays”.45 The other two Malay classes were the “civilised Malays” and the Orang Laut.46

In his views on the global progress of mankind, Crawfurd regarded the Malays and the Javanese to be the most civilised of the inhabitants of the Indian Archipelago.47 In a manner that was consistent with the philosophy of the Scottish Enlightenment of measuring the progress of mankind – which was not surprising given Crawfurd’s background and education in Edinburgh – he divided the cultures of the world into different stages of civilisation. These stages ranged from the refined to the savage, and he used cultural and material indicators to measure their level of progress, such as the development of language and numerals, advancement of social order, the advancement of the arts, tools used, weaponry, and the state of agriculture, technology, architecture and so forth.48

Crawfurd argued that (civilised) Malays were more advanced than the “Oriental Negroes” of the Malay Peninsula because they had learnt how to domesticate animals and cultivate plants, possessed the art of writing and the use of numerals, and had knowledge of useful metals and how to work them. The “Oriental Negroes” in contrast, who “wander the forests in quest of a precarious subsistence, without fixed habitation” had not yet developed letters and numbers, and had either achieved little or none of the other cultural markers mentioned above. Crawfurd also drew a connection between the practice of wearing scant clothing and savagery.49

SINGAPORE’S OTHER FOUNDER: JOHN CRAWFURD

Historian C.M. Turnbull is right in pointing out that John Crawfurd, along with Singapore’s first British Resident William Farquhar, has faded into obscurity.50 We often attribute the success and founding of modern Singapore to the man whose iconic bronze statue stands in Empress Place – Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles. As Singapore’s second British Resident from 1823 to 1826, Crawfurd was an excellent administrator who, in the words of Turnbull, “provided the efficient administration that Raffles could not supply”.51

Crawfurd guided Singapore during a time of rapid economic and population expansion.52 He promoted agriculture, battled against piracy as far as his scanty means permitted and dealt with Singapore’s lawlessness.53 He was instrumental in turning Raffles’ town plan of Singapore into a reality, enforcing standards laid down by Raffles for “beauty, regularity and cleanliness”.54

Commercial Square (present-day Raffles Place) was developed and a “bridge was constructed across the river”.55 The settlement’s streets were both widened and levelled and given English street signs, and street lamps began to emerge during his administration.56

As an enlightened liberal, Crawfurd continued Raffles’ efforts at suppressing slavery and promoted free trade with a level of zeal that was greater than his predecessor. By reducing administrative expense, he was able to abolish anchorage and other levies, making Singapore a unique port that was free from tariffs and port charges. By the end of his administration, Singapore was the wealthiest of all British settlements in Southeast Asia.

Not all of Raffles plans for Singapore were followed, however. Crawfurd reversed Raffles’ ban on gambling, regulating the practice through the sale of licences to gambling establishments.57

The Crawfurdian World View

Crawfurd used material and cultural measures to assess the state of civilisation that a race had attained. When it came to explaining how people got to where they were in society, he would identify access to domesticated animals and cultivated plants, cross-cultural engagements with a “superior” race, geography and the intellectual capacity of a race as the underlying forces that determined racial progress.58

In order for a culture to develop, according to Crawfurd’s theory, it would need access to resources that are necessary to engineer growth, such as animals that can be domesticated for work and consumption, and plants that can be cultivated.59 Contact with a superior civilisation, whether through cross-cultural engagements or conquest, could also improve a race.60

Cultures that thrive are invariably located in places that encourage development and have few geographical barriers that would impede growth, such as impregnable forests or mountains. Access to domesticated plants and animals and cross-cultural engagements are also directly tied to geography – isolated cultures cannot be expected to benefit from cross-cultural contacts, and geographical barriers could prevent a culture from obtaining the resources it needed for advancement. Crawfurd often referred to the Eskimos to corroborate his view, stating that the indigenous peoples of the Arctic and subarctic regions could hardly be expected to progress in the isolated and frozen lands they inhabited where scant plants and animals were available to help spur growth.61

Crawfurd also offered an interesting theory about the inhabitants of Britain: he believed that they would still be in a savage state, isolated in their lush forests, if the superior Romans – who introduced letters and numerals to the savage and barbaric tribes of Europe – had not conquered Britain.62 But Crawfurd was curious about the reason why some races had advanced more quickly than others, despite having the same civilisational advantages.63 Europe, for instance, seemed to be progressing at a faster pace than China. He reasoned that it was because each race had different intellectual capacities, or in Crawfurd’s words, “the quality of the race”.64 Europeans, he concluded, had the highest mental aptitude, which explained their rapid advancement and dominance during Crawfurd’s lifetime.65

Crawfurd’s theory, in a nutshell, was that racial advancement was on the whole decided by a combination of geographical, cultural and biological factors. He then applied his ideas about the progress of mankind to explain the history of the Malay Peninsula’s inhabitants, framing it within a global context. The “Oriental Negroes” of the Malay Peninsula were on a lower scale of civilisation because of their isolation in the dense forests and mountains of the interior.66 The Malays, on the other hand, had attained a certain degree of advancement in their superior Sumatran homeland before migrating to the more geographically hostile Malay Peninsula that was shrouded in dense forest, “a serious and almost insuperable obstacle to the early progress of civilisation”.67

Crawfurd thought that the Malay civilisation was much improved by its contact with Hinduism and, later, Islam, from where it obtained its letters and culture.68 Raffles, on the contrary, opined that Islam degraded the Malays69, as did the British Orientalist William Marsden.70

Crawfurd’s Perceptions of the Malay Peninsula

The Malay Peninsula and its inhabitants played an important role in Crawfurd’s writings and in shaping his views on ethnology and world history. Crawfurd’s ideas and views discussed in this essay are only a fragment of the many ways in which they informed his writings. They featured regularly in his scientific arguments, as seen in his position on the children of mixed-race unions, where he used his observations of the Peranakan communities in the British settlements to support his stand.

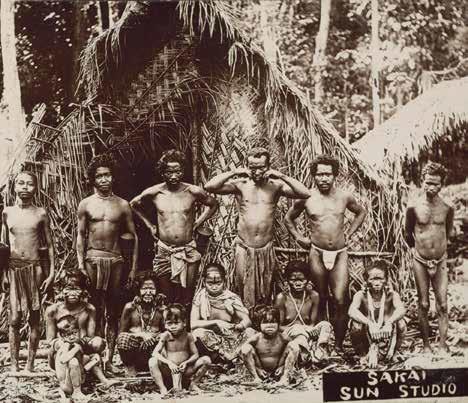

A group of Orang Asli, the indigenous people of the Malay Peninsula, late 19th century. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

A group of Orang Asli, the indigenous people of the Malay Peninsula, late 19th century. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.It is likely that Crawfurd’s perceptions would have been different if he had never stepped foot in the region. But he did, and based on his first-hand knowledge, Crawfurd applied his ethnological and scientific theories on race to his understanding of the Malay Peninsula’s history, and connected its inhabitants to the rest of mankind to formulate and advance his ideas on the history of human origins and progress.

It is clear that Crawfurd was no petty intellectual figure of the 19th century. Because his works were highly regarded and were widely read, he would have influenced how others saw the Malay Peninsula and its place in world history. The Malay Peninsula, despite what many in the West thought, was far from being a literary backwater of the British Empire, and there were others like Crawfurd – such as the British naturalist and anthropologist Alfred Russel Wallace (1823–1913) – who would feature the region in their scientific works. Crawfurd’s ideas on mankind may have promoted the idea of European racial supremacy, but a closer look at his complex works would reveal that he was probably more of a realist and a practical visionary who was more concerned about finding logical explanations to the different conditions of mankind.

Wilbert Wong was awarded the National Library’s Lee Kong Chian Research Fellowship in 2016. This article is a condensed version of a more in-depth research paper submitted as part of the fellowship. The author would like to thank his subject reviewer, Associate Professor Syed Muhammad Khairudin Aljunied, of the National University of Singapore, Dr Gareth Knapman of the Australian National University, and Dr Austin Gee of the University of Otago, for their feedback on the article. The author is also grateful for the assistance provided by Gracie Lee, Senior Librarian, National Library, Singapore, towards this research.

Wilbert Wong is currently a second-year doctoral candidate at the Australian National University's School of History, where he is researching British colonial writings on the Malay Peninsula. He hopes to specialise in the field of world history, with emphasis on crosscultural encounters.

Wilbert Wong is currently a second-year doctoral candidate at the Australian National University's School of History, where he is researching British colonial writings on the Malay Peninsula. He hopes to specialise in the field of world history, with emphasis on crosscultural encounters.

NOTES

-

Mr John Crawfurd. (1834, January 11). The Spectator, p. 32. Retrieved from The Spectator Archive website. ↩

-

Knapman, G. (2017). Race and British colonialism in Southeast Asia 1770–1870: John Crawfurd and the politics of equality (p. 20). New York: Routledge. (Call no.: RSING 325.01 KNA); Lee, G. (2016, Jan–Mar). Crawfurd on Southeast Asia, 11 (4). Retrieved from BiblioAsia website. ↩

-

Mr John Crawfurd. (1868, July 23). The Sydney Morning Herald, p. 6. Retrieved from Trove website; Turnbull, C.M. (2009). A history of modern Singapore: 1819–2005 (p. 42). Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 TUR) ↩

-

The Sydney Morning Herald, 23 Jul 1868, p. 6. ↩

-

The Sydney Morning Herald, 23 Jul 1868, p. 6; Turnbull, C.M. (2004). Crawfurd, John (1783–1868), Orientalist and colonial administrator. Retrieved from Oxford Dictionary of National Biography website ↩

-

Crawfurd, J. (1820). Advertisement. In History of the Indian Archipelago: Containing an account of the manners, arts, languages, religions, institutions, and commerce of its inhabitants. Vol. I. Edinburgh: Archibald Constable and Co. Retrieved from BookSG; Murchison, R.I. (1868). Address to the Royal Geographical Society. The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London, 38, p. clxvii. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Crawfurd, 1820, History of the Indian Archipelago, vol. I. ↩

-

Ellingson, T.J. (2001). The myth of the noble savage (p. 268). Berkeley: University of California Press. (Call no.: RSEA 301.01 ELL) ↩

-

The Sydney Morning Herald, 23 Jul 1868, p. 6; Turnbull, 2004, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. ↩

-

Notice of Mr Crawfurd’s Descriptive Dictionary. (1856). The Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia (new series), 1, p. 293. Retrieved from Hathi Trust Digital Library website ↩

-

Turnbull, 2004, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. ↩

-

Turnbull, 2004, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography; Turnbull, 2009, pp. 46–47, 50. ↩

-

The Sydney Morning Herald, 23 Jul 1868, p. 6. ↩

-

Buckley, C.B. (1984). An anecdotal history of old times in Singapore 1819–1867 (p. 141). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 BUC); Turnbull, 2009, p. 49. ↩

-

Mr John Crawfurd. (1868, May 16). The Examiner, issue 3146. ↩

-

The Sydney Morning Herald, 23 Jul 1868, p. 6; The Examiner, 1868, issue 3146; Thomson, T. (1870). A biography of eminent Scotsmen (Vol. III) (pp. 592–594). Glasgow, Blackie and Son. Retrieved from Google Books. ↩

-

See Ang, S.L. (2016, Jan–Mar). A bilingual dictionary by a Scotsman, 11 (4). Retrieved from BiblioAsia website. ↩

-

Murchison, 1868, cl. ↩

-

Knapman, G. (2016). Race, polygenesis and equality: John Crawfurd and nineteenth-century resistance to evolution. History of European Ideas, 42 (7), pp. 1, 11. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Murchison, 1868, p. clxix ↩

-

Crawfurd, J. (1865). On the supposed infecundity of human hybrids or crosses. Transactions of the Ethnological Society of London, 3, p. 365. Retrieved from Internet Archive website ↩

-

Crawfurd, 1865, On the supposed infecundity of human hybrids or crosses, p. 357. ↩

-

Crawfurd, J. (1865). On the commixture of the races of man as affecting the progress of civilisation. Transactions of the Ethnological Society of London, 3, pp. 116–117. Retrieved from Internet Archive website ↩

-

Crawfurd, 1865, On the commixture of the races of man as affecting the progress of civilisation, p. 116. ↩

-

Crawfurd, 1865, On the commixture of the races of man as affecting the progress of civilisation, p. 117. ↩

-

Crawfurd, J. (1861). On the classification of the races of man. Transactions of the Ethnological Society of London, 1, p. 356. Retrieved from Internet Archive website ↩

-

Crawfurd, 1865, On the commixture of the races of man as affecting the progress of civilisation, p. 116. ↩

-

Crawfurd, 1820, History of the Indian Archipelago, vol. I, p. 135. ↩

-

Crawfurd, J. (1820). History of the Indian Archipelago: Containing an account of the manners, arts, languages, religions, institutions, and commerce of its inhabitants. Vol. II. (p. 448). Edinburgh: Archibald Constable and Co. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Knapman, 2016, pp. 1, 11. ↩

-

Crawfurd, J. (1869). On the theory of the origin of species by natural selection in the struggle for life. Transactions of the Ethnological Society of London, 7, p. 37. Retrieved from Internet Archive website; Knapman, 2016, p. 2. ↩

-

Crawfurd, J. (1865). On Sir Charles Lyell’s “Antiquity of Man”, and on Professor Huxley’s evidence as to man’s place in nature. Transactions of the Ethnological Society of London, 3, p. 60. Retrieved from Internet Archive website; Crawfurd, 1868, On the theory of the origin of species by natural selection in the struggle for life, p. 28. ↩

-

Knapman, 2016, pp 10–14. ↩

-

Crawfurd, J. (1863). On colour as a test of the races of man. Transactions of the Ethnology Society of London, 2, p. 253. Retrieved from Internet Archive website; Crawfurd, J. (1866). On the physical and mental characteristics of the negro. Transactions of the Ethnology Society of London, 4, p. 213. Retrieved from Internet Archive website ↩

-

Crawfurd, J. (1868). On the skin, the hair, and the eyes, as tests of the races of man. Transactions of the Ethnology Society of London, 6, pp. 144–49. Retrieved from Internet Archive website ↩

-

Crawfurd, 1861, On the classification of the races of man, pp. 354, 364. ↩

-

Crawfurd, 1861, On the classification of the races of man, pp. 127, 132. ↩

-

The term “Indian Archipelago” is used by Crawfurd to refer to all countries in Southeast Asia today except Laos, Cambodia, Thailand, Burma and Vietnam. ↩

-

Crawfurd, J. (1856). A descriptive dictionary of the Indian islands & adjacent countries (pp. 295–296). London: Bradbury & Evans. Retrieved from BookSG; Crawfurd, J. (1848). On the Malayan and Polynesian languages. Transactions of the Ethnological Society of London, 1, pp. 330, 333. Retrieved from Internet Archive website; Crawfurd, 1866, On the physical and mental characteristics of the negro, pp. 230, 238. ↩

-

Crawfurd, 1848, On the Malayan and Polynesian languages, pp. 333–334; Crawfurd, 1866, On the physical and mental characteristics of the negro, p. 237. ↩

-

Crawfurd, 1820, History of the Indian Archipelago, vol. I, p. 80; Crawfurd, 1856, A descriptive dictionary of the Indian islands & adjacent countries, p. 207. ↩

-

Crawfurd, 1848, On the Malayan and Polynesian Languages, p. 333. ↩

-

Crawfurd, 1856, A descriptive dictionary of the Indian islands & adjacent countries, pp. 41, 49–50, 257. ↩

-

Crawfurd, 1856, A descriptive dictionary of the Indian islands & adjacent countries, pp. 41, 49–50, 257. ↩

-

Crawfurd, J. (1967). Journal of an embassy to the courts of Siam and Cochin China (pp. 42–44, 52–55). Kuala Lumpur, London, New York: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.3 CRA); Crawfurd, 1856, A descriptive dictionary of the Indian islands & adjacent countries, p. 250. ↩

-

Crawfurd, 1848, On the Malayan and Polynesian languages, p. 338. ↩

-

The Scottish Enlightenment, an 18th-century movement that flourished in Scotland, was still influential during Crawfurd’s time and when its impact was still felt. Edinburgh, where Crawfurd obtained his medical degree, was one of the centres of the Scottish Enlightenment. See Broadie, A. (Ed). (2003). The Cambridge companion to the Scottish Enlightenment (pp. 1, 3, 5–6). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (Call no.: R 001.0941109033 CAM); Pittock, M.H. (2003). Historiography. In A. Broadie. (Ed.), The Cambridge companion to the Scottish Enlightenment (p. 262). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (Call no.: R 001.0941109033 CAM). For an example of how Crawfurd measured progress, see Crawfurd, 1820, History of the Indian Archipelago, vol. I, p. 9; Crawfurd, 1820, History of the Indian Archipelago, vol. II, p. 276. ↩

-

Crawfurd, 1856, A descriptive dictionary of the Indian islands & adjacent countries, pp. 17, 29. ↩

-

Mills, L.A. (2003). British Malaya: 1824–67 (p. 78). Selangor, Malaysia: Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. (Call no.: RSING 959.5 MIL) ↩

-

Crawfurd, J. (1861). On the conditions which favour, retard, or obstruct the early civilization of man. Transactions of the Ethnological Society of London, 1, p. 154. Retrieved from Internet Archive website ↩

-

Crawfurd, J. (1863). On the connexion between ethnology and physical geography. Transactions of the Ethnological Society of London, 2, p. 4. Retrieved from Internet Archive website ↩

-

Crawfurd, J. (1869). On The Malayan race of man and its prehistoric career. Transactions of the Ethnological Society of London, 7, pp. 123, 125. Retrieved from Internet Archive website ↩

-

Crawfurd, 1863, On the connexion between ethnology and physical geography, pp. 4–5, 8, 10–11, 14. ↩

-

Crawfurd, J. (1820). History of the Indian Archipelago: Containing an account of the manners, arts, languages, religions, institutions, and commerce of its inhabitants. Vol. III. (p. 149). Edinburgh: Archibald Constable and Co. Retrieved from BookSG; Crawfurd, 1861, On the conditions which favour, retard, or obstruct the early civilization of man, p. 166. ↩

-

Crawfurd, J. (1863). On the commixture of the races of man in western and central Asia. Transactions of the Ethnological Society of London, 1, pp. 159–60. Retrieved from Internet Archive website ↩

-

Crawfurd, 1863, On the connexion between ethnology and physical geography, pp. 4, 14; Crawfurd, 1861, On the classification of the races of man, p. 370; Crawfurd, 1866, On the physical and mental characteristics of the negro, p. 214. ↩

-

Crawfurd, 1863, On the connexion between ethnology and physical geography, p. 16. ↩

-

Crawfurd, 1820, History of the Indian Archipelago, vol. 1, p. 118; Crawfurd, 1863, On the connexion between ethnology and physical geography, p. 11. ↩

-

Crawfurd, J. (1865). On the early migrations of man. Transactions of the Ethnological Society of London, 3, p. 339. Retrieved from Internet Archive website; Crawfurd, 1863, On the connexion between ethnology and physical geography, p. 10. ↩

-

Crawfurd, 1820, History of the Indian Archipelago, vol. II, p. 27; Crawfurd, 1856, pp. 36, 263–264; Crawfurd, 1868, On The Malayan race of man and its prehistoric career, p. 125. ↩

-

Syed Muhd Khairudin Aljunied. (2005). Sir Stamford Raffles’ discourse on the Malay world: A revisionist perspective. Sojourn, 2(1), pp. 6–8; Turnbull, 2009, p. 42. ↩

-

Quilty, M. (1998). Textual empires: A reading of early British histories of Southeast Asia (p. 52). Clayton, Victoria, Australia: Monash Asia Institute. (Call no.: RSING 959. 0072 QUI) ↩