Voices That Remain: Oral History Accounts of the Japanese Occupation

Oral history accounts of the Japanese Occupation take on added poignancy, says Mark Wong, as we mark the 75th anniversary of the Fall of Singapore.

Victorious Japanese troops marching into Fullerton Square on 16 February 1942. The British had surrendered the previous day and Singapore would be renamed Syonan-to (“Light of the South”) by its new masters. © IWM (HU 2787).

Victorious Japanese troops marching into Fullerton Square on 16 February 1942. The British had surrendered the previous day and Singapore would be renamed Syonan-to (“Light of the South”) by its new masters. © IWM (HU 2787).On 15 February 1942, the British surrender to the invading Japanese forces heralded the start of three-and-a-half years of occupation when Singapore was known as Syonan-to (“Light of the South”).

As we mark the 75th anniversary of the Fall of Singapore, we are fast approaching a turning point in our history. Anyone with a passing memory of the occupation years would be well into their 80s today, and the day will come when we can no longer obtain first-hand accounts from people who survived the atrocities of this period. This situation raises some fundamental questions about our national history: how do we know what we know about the past if no one alive has actually experienced it?

Fortunately, the National Archives of Singapore (NAS), as the official custodian of Singapore’s collective memory, has been collecting primary historical records of the war and occupation years. These take the form of government and personal documents, photographs, audio-visual recordings, maps and other formats.

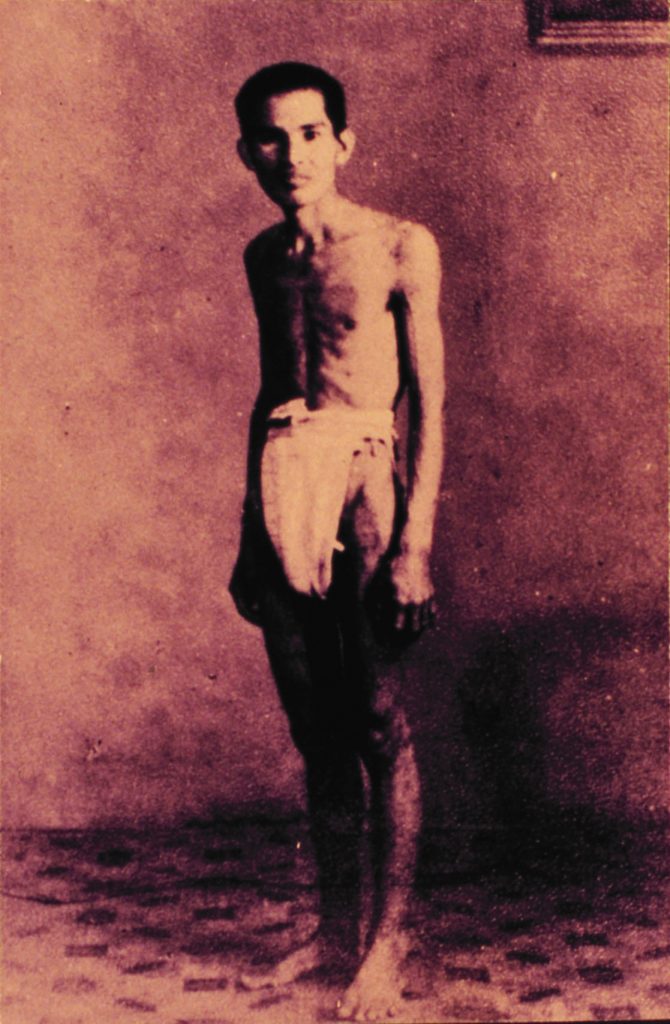

This portrait of a photographer’s assistant, taken after the Japanese Occupation, clearly shows the effects from the years of deprivation. All rights reserved, Lee, G. B. (1992). Syonan: Singapore Under the Japanese 1942–1945 (p. 44). J. H. Siow (Ed.). Singapore: Singapore Heritage Society.

This portrait of a photographer’s assistant, taken after the Japanese Occupation, clearly shows the effects from the years of deprivation. All rights reserved, Lee, G. B. (1992). Syonan: Singapore Under the Japanese 1942–1945 (p. 44). J. H. Siow (Ed.). Singapore: Singapore Heritage Society.Giving a Voice to the Past

The shift from living memory to official archives gives us occasion to re-evaluate the significance of the NAS’s Japanese Occupation of Singapore Oral History Collection. In 1981, the Oral History Unit (OHU; now renamed as the Oral History Centre) launched a major project to record memories of the Japanese Occupation of Singapore. Although it was the impending and inevitable loss of Singapore’s wartime generation that prompted this effort, the idea of collecting interviews about the war and occupation had been conceived when the OHU was first established in 1979.1

That year, the OHU announced plans to embark on two key projects – “Pioneers of Singapore” and “Political Development of Singapore, 1945–1965”;2 the third project on the Japanese Occupation would be on hold until “more experience has been obtained by the Unit”.3

The first two projects were narrower in their scope and selection of interviewees. The Pioneers initiative (at one time also referred to as the Millionaires project4) recorded the recollections of business and social leaders from the early- to mid-20th century, while the Political Development project focused on political leaders familiar with the rise of politics in the period after World War II up to Independence.5

Both projects were attempts to understand history through the movers and shakers of society. The Japanese Occupation project, however, aimed to record history from a variety of perspectives – and would cut across socioeconomic lines.

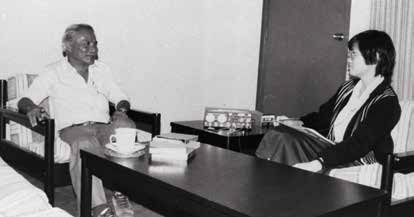

An interview in progress – using the Uher Report Monitor 4200 open-reel tape recorder − at the Oral History Department in Hill Street in 1982. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

An interview in progress – using the Uher Report Monitor 4200 open-reel tape recorder − at the Oral History Department in Hill Street in 1982. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.The first phase of the Japanese Occupation project took four-and-a-half years, from June 1981 to December 1985.6 Potential interviewees were identified through “media publicity,7 organisations like the National Museum, Sentosa Museum, Senior Citizens’ clubs, community centres, individual recommendations and handbills distributed at pictorial exhibitions organised by the National Archives of Singapore”.8 At the close of the project, 175 persons had been interviewed, totalling some 655 recorded hours.

Subject to conditions placed by the interviewees, the recordings were made available to government officials, researchers and members of the public. The first major showcase of the interviews took place in February 1985 on the 43rd anniversary of the Fall of Singapore.9

For one month, the Archives and Oral History Department (OHD) – the entity formed by the merger of the National Archives and Records Centre and the OHU in early 198110 − organised a month-long exhibition on the Japanese Occupation at its former premises at Hill Street Building (today’s Old Hill Street Police Station).11

This first-ever exhibition on the occupation years12 used information that had been gathered from oral history interviews as well as a selection of pictures, maps, charts and documents.13 Many of the artefacts displayed were either donated or borrowed from the interviewees.14

A year later, to mark the end of the first phase of the project, the OHD published a catalogue of interviews containing information such as date, duration and synopses. Recognising that there are more stories to be told, the project continues to this day whenever suitable interviewees are found.

The Value of Oral History

Today, the Oral History Centre (OHC), as it was finally renamed in 1993, is a unit under the NAS. Altogether, it has amassed over 360 interviews and 1,100 hours of recordings pertaining to the Japanese Occupation.15 These interviews have become a key collection of the OHC for a number of reasons.

Most importantly, the interviews have helped to fill an enormous gap in our knowledge of the war and occupation. The chaos of war and the regime change posed many challenges for record-keeping, made worse in the final days leading up to the official Japanese surrender on 2 September 1945 when the administration systematically destroyed records of its work in Singapore. Copies of the heavily censored Syonan Shimbun and other newspapers that survived, while providing a valuable record of daily life in Singapore, mostly presented positive, if not glowing, views of the Japanese administration.

The Japanese Occupation interviews have helped to shed light on the harsh realities of life in Syonan-to, the large number of interviewees often proving to be effective in corroborating (or disqualifying) competing claims. Interviewees were selected based on their first-hand familiarity with the subject matter. Structured outlines were used to ensure some measure of consistency and uniformity in the topics covered, while interviewers were trained to pick up on unique experiences for follow-up.

Weighing in on the significance of the Japanese Occupation collection, James H. Morrison writes:

“In a virtual lacuna of documentation contemporaneous with the event, remembrances either spoken or written are, of course, prime documentation…. The Singapore Oral History Department’s collection of materials on the Japanese Occupation during the Second World War is meticulously collected, scrupulously organized, and immediately accessible to users. They provide one of the more comprehensive collections of one former colony’s view (or views) of the war.”16

As the project was intent on collecting data that would enable the reconstruction of the lives of those affected by the Japanese Occupation − both civilians as well as military personnel − a broad approach was taken to include several key themes. These include the pre-war anti-Japanese movement; the British defence of Singapore; social and living conditions under occupation; the Sook Ching massacres; the Japanese defence of Syonan-to against the Allied Forces; the role of the resistance forces; and the Japanese surrender and its aftermath.

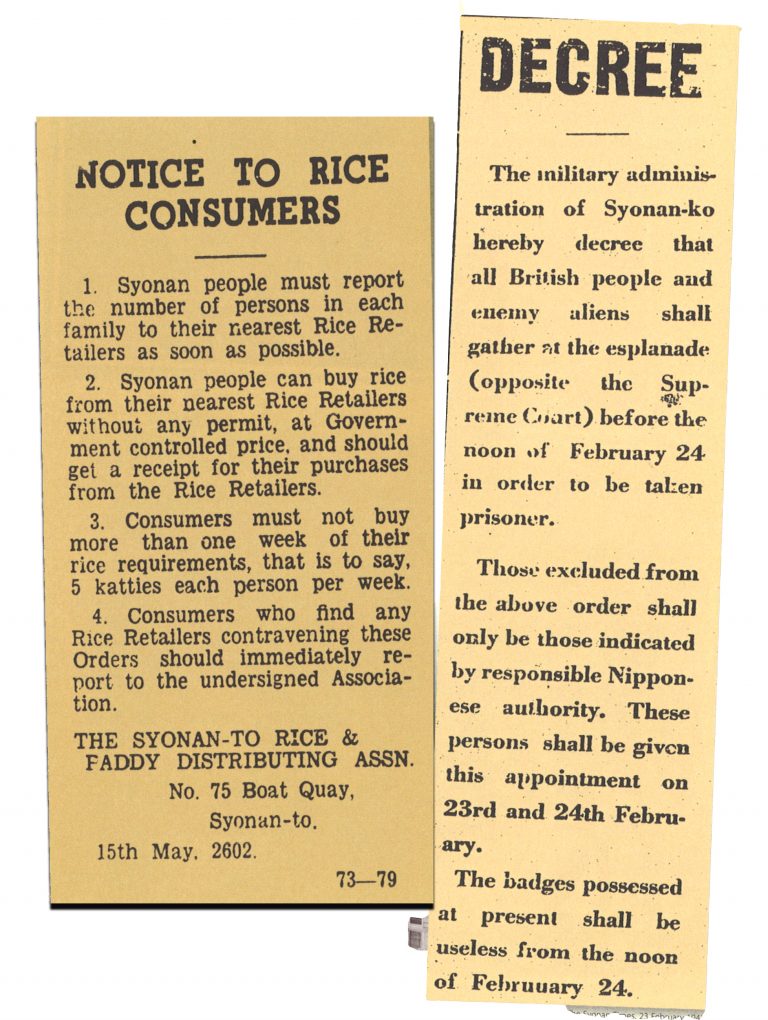

Public notices such as these became commonplace during the Japanese Occupation. The first is an order to purchase rice supplies in rationed amounts only from licensed retailers. The Syonan Times 18 May 1942, p. 5. The second notice is an order for all military personnel and European civilians to assemble at the Esplanade following the British surrender on 15 February 1942. The Syonan Times 23 February 1942, p. 4.

Public notices such as these became commonplace during the Japanese Occupation. The first is an order to purchase rice supplies in rationed amounts only from licensed retailers. The Syonan Times 18 May 1942, p. 5. The second notice is an order for all military personnel and European civilians to assemble at the Esplanade following the British surrender on 15 February 1942. The Syonan Times 23 February 1942, p. 4.The intention was to record a plurality of voices so that they could serve as a counterbalance to the predominantly Western-centric memoirs of British and Australian soldiers and politicians that had begun appearing after the war and the types of histories that were subsequently written. The Fall of Singapore has been framed as Britain’s worst military disaster – but what did occupation really mean for people in Singapore?

To this end, the interviews systematically record experiences from a broad spectrum of individuals, spanning gender, nationality, ethnicity, religion and socio-economic background. There are accounts by volunteer forces, prisoners-of-war, civilian internees, resistance fighters, government servants, businessmen, British, Australians, Chinese, Malays, Indians, Japanese and more. Speaking in different voices and languages, they relate their lived experiences and communicate the complexities of deep emotions and scarred memories, providing a multifaceted view of this significant period of Singapore history.

The interviews cover themes beyond the shores of Singapore, including experiences in Malaya, the Dutch East Indies, Thailand, China and Japan – underscoring the regional significance of the occupation of Singapore. There are accounts of resettlements to Endau and Bahau in Malaya and movements of prisoners-of-war to different parts of occupied Southeast Asia and even Japan. There are also stories of the Nanqiao Jigong (南桥机工), a group of volunteer mechanics and drivers of mostly Chinese ethnicity from all over Southeast Asia who aided the war effort against the Japanese in China by bringing supplies through the 1,146- km Yunnan-Burma Road as well as mass movements of British covert forces and anti- Japanese guerrilla groups in Malaya. Former British and Australian internees also speak of their traumatic post-war years adjusting back to life in their homelands.

A father and daughter having a simple meal of porridge and nuts. During the Japanese Occupation, many people suffered from malnutrition or died of starvation. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

A father and daughter having a simple meal of porridge and nuts. During the Japanese Occupation, many people suffered from malnutrition or died of starvation. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.With access to such a broad range of interviews, one realises that there is no singularly defining experience of the war and occupation, but multiple ones. Listening to so many different individuals provides new insights that can help clear up preconceptions or myths of the occupation. The Japanese Occupation scholar Clay Keller Eaton expresses it succinctly:

“I use a lot of memoirs in my work, but with a few notable exceptions the people whose memoirs get published in both Japan and Singapore tend to have held positions of power during the occupation. One of the greatest strengths of [the] ‘Japanese Occupation of Singapore’ oral history project is that it covers a wide cross section of Singaporean society… some of the interviews I’ve found most valuable were of poorer or marginalized Singaporeans whose experiences don’t fit easily into the dominant narratives of the occupation.… I came into the oral history interviews with this idea that the Japanese administration was omnipresent in wartime life because of organizations like the Overseas Chinese Association, Eurasian Welfare Association, and the auxiliary police force. However, through the interviews of the city’s poorer residents like Mabel [de Souza],17 I found that the Japanese Occupation state was actually less present the further down you were on the socioeconomic ladder.… I did start to get a sense that the Japanese were far more interested in co-opting and controlling the elites of Singapore, and that marginalized peoples (whether by race or socioeconomic status or gender) had a peculiar sort of anonymity in the occupied city. Some might not consider these people to be ‘significant,’ but their experiences provide an important corrective to standard narratives of the war.”18

An Emotional Connection

Over time, one can become easily disconnected from a past that may seem so far removed from our present. Oral history accounts can help us find an emotional connection to narrators, who engage us through nuances in voice, pitch, tone, pace, mood, expression and more. We may not always comprehend their circumstances, but we can recognise their emotions of joy, anger and fear, and ultimately understand history through a rich tapestry of highly personal and subjective perspectives.

This is why oral history has been a lynchpin of the NAS’s efforts to document the war and occupation. In a book review of The Price of Peace: True Accounts of the Japanese Occupation,19 the critic writes: “The most compelling stories here are the first-hand accounts of wartime resistance activities, culled from the Oral History Centre’s collection of interviews with survivors.”20 There is something riveting about listening to a spoken first-person account of an event that third-person narratives can never hope to capture.

Oral history has continued to engage the public imagination ever since that first exhibition on the Japanese Occupation in 1985. The interpretive centre, “Memories at Old Ford Factory”, opened at the Former Ford Factory − the site of the British surrender − on Upper Bukit Timah Road on 16 February 2006. The exhibition was a stark reminder of the horrors of the war and occupation. Eleven years later, on 15 February 2017, a new exhibition, “Surviving the Japanese Occupation: War and its Legacies”, took its place.

Singapore’s wartime survivors will not be around forever, but their voices will be preserved in the Japanese Occupation of Singapore’s Oral History Collection so that we and the generations who come after us can continue to listen – and learn − from their experiences.

VOICES FROM THE OCCUPATION

“When the Japanese came in, during the first fortnight, they beheaded eight people and their heads were put into iron cages and hung up at eight different places and notices were put out beside the heads that ‘These eight people were beheaded because they disobey the law of the Imperial Japanese Army’… The notice spelled out that if anyone caught in the act would be given the same treatment.” – Neoh Teik Hong21

“My father and two uncles were required to report to some registration centre – I don’t know whether [it was] a police station or what, I’m not so sure. Three of them went and only two came back.” – Foong Fook Kay22

“The rice ration we get from our shop was hardly sufficient for our requirement… We chopped the tapioca into small pieces, combined it with the rice and used it as rice… We all were thin, skinny, sickly… Very hard life. I tell you honestly, not worth living during Japanese time. Better to die than to live. Another year… if the Japanese were here, I think a lot of people would have died from malnutrition.” – Ismail bin Zain23

“Every term about two or three songs will be sent out to the schools and it was our job to ensure that the schools were learning these songs… They were mostly military war songs, marching songs, Japanese patriotic songs… Of course, many of us did not know the meanings of those words at that time… The policy was partly to propagate Japanese culture and propaganda through the use of songs.” – Paul Abisheganaden24

“Unlike the… the Westerners, like the Americans or the British, who would conceal any knowledge that they felt should not be imparted to others, other than their own people… the Japanese did not mind teaching us, so that the people of this land could learn how to maintain a plane, how to maintain a ship, how to do certain things….” – Mahmud Awang (translation of interview in Malay)25

Mark Wong is an Oral History Specialist at the Oral History Centre, National Archives of Singapore, where he conducts oral history interviews in areas such as education, the performing arts, the public service and the Japanese Occupation. He co-curated the exhibition, "Law of the Land: Highlights of Singapore’s Constitutional Documents", now on at the National Gallery Singapore.

Mark Wong is an Oral History Specialist at the Oral History Centre, National Archives of Singapore, where he conducts oral history interviews in areas such as education, the performing arts, the public service and the Japanese Occupation. He co-curated the exhibition, "Law of the Land: Highlights of Singapore’s Constitutional Documents", now on at the National Gallery Singapore.

NOTES

-

Special unit set up for oral history. (1979, December 15). The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Kwa, C.G. (2005.) Desultory reflections on the Oral History Centre (p. 5). In D.Chew & F.Hu. (Eds.), Reflections and interpretations: Oral History Centre 25th anniversary publication. Singapore: Oral History Centre, National Archives of Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 907.2 REF) ↩

-

Man from Unesco for Oral History Unit. (1979, December 15). The Business Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

All that you wanted to know about millionaires. (1982, September 14). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Chew, E. (1986). Foreword (p. iii). In Syonan: Singapore under the Japanese: A catalogue of oral history interviews. Singapore: Oral History Department. (Call no.: RSING 959.57023 SYO) ↩

-

Oral history project on the Japanese Occupation. (1981, July 31). The Straits Times, p. 10; Wanted for the record – memories of days gone by. (1981, June 23). The Straits Times, p. 16. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Tan, B.L. (1986). Preface (p. iv). In Syonan: Singapore under the Japanese: A catalogue of oral history interviews. Singapore: Oral History Department. (Call no.: RSING 959.57023 SYO) ↩

-

Mudali, D. (1985, February 16). Eye-opener for two anti-war Japanese. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ministry of Culture. (1984, May 26). Speech by Mr S Dhanabalan, Minister for Foreign Affairs and Minister for Culture, at the official opening of the Archives and Oral History Department at Hill Street Building and pictorial exhibition “Singapore 1819 to 1980: Road to Nationhood” on Saturday, 26 May 1984 at 11:00 am (pp. 2–3). Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Exhibition recalls life under the Japanese. (1985, January 22). The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG ↩

-

Fall of Singapore remembered in exhibition. (1985, February 3). Singapore Monitor, p. 4; Sam, J. (1985, January 13). Under the ‘occupation’. Singapore Monitor, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Hoe, I. (1985, February 16). Timely reminder of hard times 40 years ago. The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Sam, J. (1984, September 16). Japanese Occupation photos and artifacts to go on show. Singapore Monitor, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

This figure comprises two wartime oral history projects – Japanese Occupation of Singapore and Prisoners of War. Interviews conducted for other projects may also contain some information about wartime experiences. ↩

-

Morrison, J. H. (1994). Japanese Occupation of Singapore: Oral sources. Canadian Oral History Association Journal, 14, 92–95. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Low, L.L. (Interviewer). (1984, January 26). Oral history interview with De Souza, Mabel (Mrs) @ Mabel Ottzen [Transcript of cassette recording no. 000393/04/01]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Eaton, C.K. (2017, February 2). Email correspondence with author. Eaton contributed a vignette based on the OHC’s interview of Mabel de Souza. See Chandler, D.P., Cribb, R., & Li, N. (Eds.). (2016). End of empire. 100 days in 1945 that changed Asia and the world (pp. 130–131). Copenhagen: NIAS Press. (Call no.: RSEA 303.4825052 END); Eaton, C. (n.d.). Mabel’s life goes on. Retrieved from End of Empire website. ↩

-

Foong C.H. (Ed.). (1997). The price of peace: True accounts of the Japanese Occupation. Singapore: Asiapac. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 PRI) ↩

-

Ong, S.F. (1997, June 21). Compelling stories of survival. The Straits Times, p. 26. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Tan, B.L. (Interviewer). (1984, October 24). Oral history interview with Neoh Teik Hong [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 000107/04/01, pp. 7–8]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Wong, M.W.W. (Interviewer). (2010, April 20). Oral history interview with Foong Fook Kay (Major) (Retired) [MP3 recording no. 003506/07/01]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website ↩

-

Tan, B.L. (Interviewer). (1985, September 5). Oral history interview with Ismail bin Zain [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 000601/05/02, p. 23]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Chua, J.C.H. (Interviewer). (1994, February 23). Oral history interview with Paul Abisheganaden @ Paul Selvaraj Abisheganaden [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 001415/48/13, pp. 166–168]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Mohd Yussoff Ahmad (Interviewer). (1982, October 30). Oral history interview with Mahmud Awang [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 000224/32/06, pp. 53–54]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩