An Unusual Ambition: The Early Librarians

Bonny Tan traces the careers of little-known librarians, Padma Daniel and her mentor Kate Edith Savage-Bailey, and the circumstances that led to their career choices in pre-war Singapore.

Exterior view of the Raffles Library and Museum at Stamford Road in this photo taken in the 1930s, during the time when Padma Daniel and Kate Edith Savage-Bailey were working there as librarians. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

Exterior view of the Raffles Library and Museum at Stamford Road in this photo taken in the 1930s, during the time when Padma Daniel and Kate Edith Savage-Bailey were working there as librarians. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.“A rather unusual ambition” wrote Reverend Basil Colby Roberts, the Singapore Anglican Bishop, in a letter dated 11 December 1935 to Frederick N. Chasen, then Director of the Raffles Library and Museum.1 Roberts was endorsing Padma Daniel in her application as a volunteer at the library.

It was an unusual ambition on many fronts. First, the Library Association in Britain had stringent requirements for prospective librarians. Besides passing a qualifying exam, applicants were required to have at least three years’ experience working in a library. Second, the library domain was very much a man’s world, with most qualified librarians and library patrons being primarily Caucasian and male. Padma was possibly the first local woman seeking a career in librarianship.

The First Library Opens

The earliest record of a local employed as a librarian in Singapore is that of Ram[a]samy Pillay who, in 1837, was paid a monthly salary of $4 as Assistant Teacher and Librarian of the Singapore Free School. He had excelled in his studies, and was likely a fresh graduate and untrained in librarianship. The school library housed a modest collection of fewer than 400 volumes although members of the public could also join as subscribers.2

On 22 January 1845, the library was renamed the Singapore Library. This was the first public library in Singapore, serving primarily paying subscribers. Some three decades later, on 1 July 1874, the colonial government took over the running of the library, officially adding to it the functions of a museum, relocating the premises to Stamford Road and renaming it Raffles Library and Museum.3

Meanwhile, British libraries came under the umbrella of the UK’s Library Association, which was formed in 1877. Besides promoting libraries and looking after the professional standards of librarians, it held biannual qualifying examinations for would-be librarians in the British Empire.

However, it was not until 1920 that a qualified librarian, James Johnston, was recruited from Britain to manage the Raffles Library. Some of his key accomplishments during his 15-year tenure included the opening of the Junior Library for children on 21 July 1923, billed as “the first of its kind in Malaya”;4 and the establishment of the Malaysia Room in 1926, otherwise known as the “Q” Room5 – the latter was a reference to the shelf mark that identified works on the Straits Settlements, Malaya and the Malay Archipelago.

The Seeds of Librarianship

The Junior Library and the Malaysia Room were likely factors that influenced locals to consider taking up a career in librarianship. However, Padma’s interests in books and reading were likely nurtured from an early age at home.

Family Influence

Padma Daniel was born on 31 August 1919, the eldest child of George O. Daniel and Harriet Fletcher, ethnic Indians from Travancore, India. George’s interest in books likely began as a young boy when his active involvement at church in India led him to meet an English expatriate with an extensive home library.6

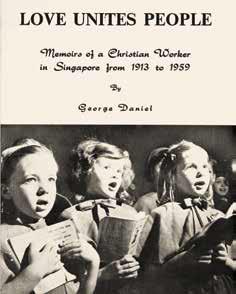

George Daniel’s book, Love Unites People: Memoirs of a Christian Worker in Singapore from 1913 to 1959. Published in 1959, the book makes references to the life of his daughter, Padma Daniel. All rights reserved, Daniel, G. (1959). Love Unites People: Memoirs of a Christian Worker in Singapore from 1913 to 1959. Singapore: G. Daniel. (Call no.: RCLOS 275.957 DAN)

George Daniel’s book, Love Unites People: Memoirs of a Christian Worker in Singapore from 1913 to 1959. Published in 1959, the book makes references to the life of his daughter, Padma Daniel. All rights reserved, Daniel, G. (1959). Love Unites People: Memoirs of a Christian Worker in Singapore from 1913 to 1959. Singapore: G. Daniel. (Call no.: RCLOS 275.957 DAN)He continued this interest in books, mainly Christian publications, first working in Rangoon, Burma, for five years, managing the Rangoon Diocesan Magazine for the Anglican Diocese,7 before being appointed as Honorary Secretary and Treasurer for the Diocesan Magazine in Singapore in 1917.8

In Singapore, he also managed the Book Depot – which in time became informally known as Daniel’s Depot – a supplier of Christian books as well as books “both ancient and modern”.9 Early advertisements for the Book Depot included listings of books for boys and girls, dictionaries, art picture books and novels.10 Padma likely had privileged access to many of these titles and invariably developed a love for reading.

The Junior Library

When the Junior Library first opened on 21 July 1923, it was housed in a large room on the ground floor next to the Raffles Library’s Public Room.

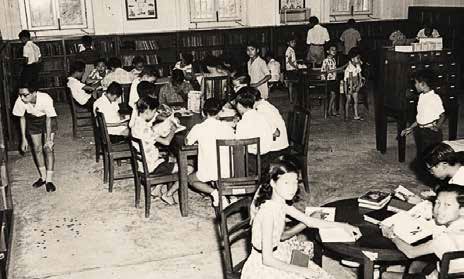

The Junior Library at the Raffles Library, c. 1950s. The low wooden tables and chairs were specially designed for children’s use. The wooden 20-compartment catalogue card cabinet can be seen on the right-hand side of the photograph. Image source: National Library Board, Singapore.

The Junior Library at the Raffles Library, c. 1950s. The low wooden tables and chairs were specially designed for children’s use. The wooden 20-compartment catalogue card cabinet can be seen on the right-hand side of the photograph. Image source: National Library Board, Singapore.The Junior Library had a collection of more than 1,000 books, among which were Greek classics such as the Iliad, Odyssey and Aeneid as well as works by famed writers like Daniel Defoe, Jules Verne, R. L. Stevenson, R. M. Ballantyne and Mark Twain. Johnston the Librarian said of the collection in February 1930:

“It might be of interest to some to know that many of the local children whether Malay, Chinese, or Indian are just as ready to read and enjoy the tales by these authors with the same enthusiasm as boys in England….”11

In truth, a survey of the reading tastes of children at the Junior Library in 1938 revealed a diet of mainly fairy tales and annuals.12 A regular column in The Straits Times on 13 September 1936, had this to say: “One of the curious things about the growth of English education in Malaya is the popularity of the ‘twopenny weeklies’ among the Asiatic.”13

Popular children’s magazines such as The Children’s Newspaper, The Boy’s Own Paper and Meccano Magazine took up to a month to be shipped from England, and the original cost of two pence apiece would be raised to 12 cents upon arrival. Those in the know would purchase cheaper, secondhand copies or unsold editions but it was still cheaper to get hold of these popular reads at the Junior Library.

Early Student Writings

The growing interest in reading among students sparked an interest in writing. A regular column for older boys titled “Boys’ Corner” made its appearance in The Malaya Tribune in 1930 with contributions from the boys at Raffles Institution, St Joseph’s Institution and Anglo-Chinese School.14

Not to be left out, there were calls for a “Girls’ Corner” in early 1931 but the editors, concerned that interest could not be sustained, suggested that the girls contribute to the existing “Women’s Corner” instead.15 Nevertheless by May 1931, a writer using the pseudonym “Cicily” created a furore when her article was published in “Boys’ Corner”. The article was essentially a complaint about boys from certain distinguished schools who loitered at street corners to harass and ogle at girls.16

The growing interest in reading among students sparked an interest in writing. A regular column for older boys titled “Boys’ Corner” made its appearance in The Malaya Tribune in 1930. By 20 May 1931, “Girls’ Corner” had become a regular feature. The Malaya Tribune, 23 June 1932, p. 11 and 12 January 1935, p. 2.

The growing interest in reading among students sparked an interest in writing. A regular column for older boys titled “Boys’ Corner” made its appearance in The Malaya Tribune in 1930. By 20 May 1931, “Girls’ Corner” had become a regular feature. The Malaya Tribune, 23 June 1932, p. 11 and 12 January 1935, p. 2.After several appeals, an attempt was made in the 9 May 1931 edition of The Malaya Tribune with the publication of an article, “To Bob or not to Bob”, by a writer named “Evelyn” and the promise of a weekly Wednesday column if successful.17 By 20 May, the “Girls’ Corner” had become a regular feature. One contributor suggested that girls leave the “high-brow” subject of fashion and love to the “Women’s Corner” and concentrate on games, arts and other topics that would appeal more to a modern schoolgirl.18 Invariably, many of the contributors to the Girls’ Corner were from the Raffles Girls’ School, some of whom were Padma’s contemporaries.

The Challenges

Despite their vociferous voices, girls remained in the minority, both as contributors to newspaper columns and as patrons of the library. When the Junior Library first started in 1923, there were 365 subscribers with 278 of them being boys, mainly students of nearby schools.19 A decade later in 1933, the number of subscribers had grown to more than 1,000, although girls only constituted a small fraction at 12 percent. Most of the female subscribers were students of Raffles Girls’ School, where Padma studied.

Interestingly, when the Junior Library first opened, fiction books were shelved separately for boys and girls. There were also different opening days for the sexes: Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays were reserved for girls, while Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays were for boys. By 1929, this gender segregation had been removed.

However, there remained other barriers for both boys and girls in joining the library. At $2 a year or 50 cents a quarter, not everyone could afford the subscription fee. Added to this was the library’s distance from those living in the suburbs and its restrictive opening hours. The Straits Settlements (Singapore) Association “believed that the Raffles Library fails, by reason of its high cost and its situation and hours, to appeal to considerable sections of the English speaking and English reading public which have small means and little spare time”. It called for branch libraries and reading rooms to be established in the suburbs.20

The Making of a Librarian

It was against this backdrop that Padma Daniel first emerged on the library scene. Much of what is known of Padma has been gleaned from her father’s letters of introduction and appeal for employment. By 1 January 1936, the request for employment had been approved and Padma began her volunteer position as an unpaid apprentice at the Raffles Library.

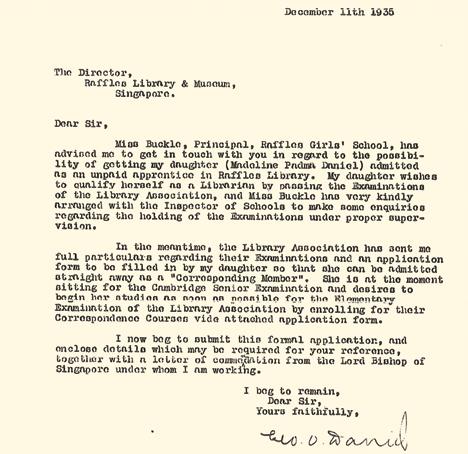

George Daniel’s letter dated 11 December 1935 to the Director of the Raffles Library and Museum asking if the Raffles Library would consider admitting his daughter, Padma Daniel, as an unpaid apprentice. The application was successful and Padma began her apprenticeship at the Raffles Library in January 1936. Image source: Colonial Secretary Office paper 6414 dated 1938 [CSO 6414/1938].

George Daniel’s letter dated 11 December 1935 to the Director of the Raffles Library and Museum asking if the Raffles Library would consider admitting his daughter, Padma Daniel, as an unpaid apprentice. The application was successful and Padma began her apprenticeship at the Raffles Library in January 1936. Image source: Colonial Secretary Office paper 6414 dated 1938 [CSO 6414/1938].By this time, the librarian James Johnston had retired and in his place was Kate Edith Savage-Bailey. She had arrived in Malaya in 1910 with her husband Arnold Savage-Bailey, a well-known solicitor who became partner at a law firm in Kuala Lumpur, and later in Penang. An unfortunate accident led to his sudden demise on 1 April 1935.21

Kate chose to remain in Malaya after the tragedy, moving to Singapore to take up the position of temporary librarian at the Raffles Library on 13 September 1935.22 When Padma joined the library, Kate had only served a mere four months. Padma was about four years older than Kate’s youngest daughter, Dulcie Gray. Besides being Padma’s supervisor, Kate may have been a mother-figure who inspired Padma to further her reading and research interests. Padma would have witnessed Kate introducing major changes at the Raffles Library during her first year of service.

This included opening the Raffles Library half an hour earlier at 8.30 am.23 When Kate’s contract was extended for another two years of service, she turned her energies to the heritage collections. She installed new bookcases in the Malaysia Room, and published the J. V. Mills Map Collection Index to make the maps more accessible. For home loans, Kate made arrangements for more open access, including purchasing duplicate titles.24

Outside library duties, Kate regularly contributed articles to The Straits Times on topics relating to Malaya, such as living and travelling in Malaya, on local domestic help, and Malayan architecture. She republished her children’s book, Squee- umph!! A Malayan Elephant (1929), in 1934, and released The Jungle Omnibus, a collection of four short stories about Malayan animals, in 1936. The Malaya Tribune praised the book for its “pure and fluent” style and commented that “it is the type of book which will give delight as well as instruction, and it should be in the possession of all children in this country who are being taught English”.25 Between March and June 1937, she gave frequent talks on the radio, most of which were readings of her children’s books.

Kate Edith Savage-Bailey, librarian at the Raffles Library, published her children’s book, The Jungle Omnibus, a collection of four short stories about Malayan animals, in 1936. The Straits Times, 3 December 1936, p. 1.

Kate Edith Savage-Bailey, librarian at the Raffles Library, published her children’s book, The Jungle Omnibus, a collection of four short stories about Malayan animals, in 1936. The Straits Times, 3 December 1936, p. 1.Padma’s Legacy

Having served three years, Kate went on a year’s furlough from September 1938 until July 1939, during which time the Raffles Library was placed under the charge of Mrs. C. B. Rea.26 Meanwhile, Padma was confirmed as a Junior Assistant Librarian on 1 October 1938, having passed her Library Association examination in December the previous year. Whilst preparing for her next examination in December 1940, Padma continued with her two-year correspondence course on top of her work at the library. Her father had written in to ask if a paid position as Junior Librarian would be offered to her upon completion of the full course, but the reply is not known.27

In 1938, Tan Soo Chye, a local graduate of Raffles College, filled the newly created position of archivist at the Raffles Museum. While his time was spent organising the archives, he also began to work on “a paper on the location, nature and condition of the Straits Settlements’ archives”.28

Around this time, Padma likely began work on her bibliographic listing of books in the Malaysia Room. This was a comprehensive listing of titles in the Raffles Library and Museum relating to Malaya, a collection that Kate had worked on previously and which Padma was likely to have helped organise. Padma’s compilation was eventually published in December 1941 as A Descriptive Catalogue of the Books Relating to Malaysia in the Raffles Museum & Library, Singapore.

The onset of World War II, however, put a halt to Padma’s career. With the Japanese troops advancing down the Malay Peninsula, Padma evacuated to Bombay, India, on 8 January 1942, just weeks before Singapore fell. She was soon followed by her mother and two siblings. Another brother was already safe in Delhi, studying at St Stephen’s College, but one stayed behind to serve in the Medical Auxiliary Service in Singapore. Her father remained behind to manage the Book Depot, by then known as the SPCK Churchshop. He lost all contact with the family until they were reunited towards the end of the Japanese Occupation in 1945.29

Unfortunately, Kate did not survive the war. The ship she boarded, the S.S. Rooseboom, which was heading for Padang in late February 1942, was sunk by a Japanese submarine near Batavia.30

After the war, Padma’s catalogue remained one of the few available for purchase. Costing $3.50, it was used to rebuild the Malayan Collections as it listed key prewar titles, including fictional works with a local setting.31 On her return to Malaya, Padma moved to Kajang, Selangor.32 Little else is known of Padma thereafter or whether she fulfilled her “unusual ambition” of becoming a qualified librarian.

Both Padma’s catalogue and Kate’s The Jungle Omnibus are available on microfilm at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library, National Library Building.

The author would like to acknowledge the help of Gracie Lee, Senior Librarian at the National Library, and Fiona Tan, Assistant Archivist at the National Archives of Singapore.

Bonny Tan is a former Senior Librarian at the National Library, Singapore. She currently resides in Vietnam with her family and is a regular contributor to BiblioAsia.

Bonny Tan is a former Senior Librarian at the National Library, Singapore. She currently resides in Vietnam with her family and is a regular contributor to BiblioAsia.

NOTES

-

Colonial Secretary Office paper 6414 dated 1938 [CSO 6414/1938]. ↩

-

Singapore Institution Free School: Fourth annual report, with appendix and catalogue of books now in the library, 1837–1838 (pp. 16, 18, 23). (1838). Singapore: Singapore Free Press. (Call no.: RRARE 373.5957 SIN); Seet K.K. (1983). A place for the people (p. 13). Singapore: Times Books International. (Call no.: RSING 027.55957 SEE) ↩

-

Makepeace, W., Brooke, G.E., & Braddell, R.St.J. (Eds.). (1991). One hundred years of Singapore (Vol 1, pp. 544–545). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 ONE); Seet, 1983, p. 23. ↩

-

Raffles Library and Museum. (1924). Annual report 1923 (p. 9). Singapore: The Museum. (Call no.: RRARE 027.55957 RAF; Microfilm nos.: NL2874, NL25786, NL5723) ↩

-

Raffles Library and Museum, 1927, p. 7. ↩

-

Daniel, G. (1959). Love unites people: Memoirs of a Christian worker in Singapore from 1913 to 1959 (pp. 6–7). Singapore: G. Daniel. (Call no. RCLOS 275.957 DAN) ↩

-

Singapore Diocesan Magazine. (1917, February 14). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Daniel, 1959, pp. 22–23; St Andrew’s cathedral. (1921, August 16). The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Page 21 advertisement column 1. (1927, September 10). The Malayan Saturday Post, p. 21. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Johnston, J. (1930, February 21). Supplementing juvenile education, The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

‘No heavy stuff’, say Singapore readers. (1938, December 4). Sunday Tribune (Singapore), p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. [Note: Annuals were popular children’s publications that were published once a year.] ↩

-

The Onlooker. (1936, September 13) Mainly about Malayans. The Straits Times, p. 16. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Liang, E.R. (1930, December 4). Come along, boys. The Malaya Tribune, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

“Desirous Girl”. (1931, February 14). A Girls’ Corner? The Malaya Tribune, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

“Cicily”. (1931, May 7). Street corner idling. The Malaya Tribune, p. 3; “Cicily”. (1931, May 21). Boys and street corner idling. The Malaya Tribune, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

“Evelyn”. (1931, May 9). To bob or not to bob. The Malaya Tribune, p. 4; Page 2 advertisements column 2. (1931, May 9). The Malaya Tribune, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

“Progress”. (1931, May 20). Girls’ Corner. The Malaya Tribune, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Raffles Library and Museum, 1924, p, 10. ↩

-

Raffles Library may be made more useful to community. (1940, May 22). The Malaya Tribune, p. 2 Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Mr. A. Savage Bailey killed by fall from ship. (1935, April 2). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Raffles Library and Museum, 1936, p. 1. ↩

-

Raffles Library and Museum, 1936, pp. 11, 14. ↩

-

Raffles Library and Museum, 1937, p. 16. ↩

-

Book for Malayan children – Jungle omnibus of Mrs Savage-Bailey. (1936, November 30). The Malaya Tribune, p. 16. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Raffles Library and Museum, 1939, p. 16; Raffles Library and Museum, 1940, p. 1. ↩

-

CSO 6414/1938. ↩

-

Raffles Library and Museum, 1939, p. 1. ↩

-

Pether, M. (2013, May). SS. Rooseboom. Retrieved from The South African Military History Society website. ↩

-

Rebuilding your library. (1947, August 7). The Singapore Free Press, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩