Murder Most Malevolent

Sunny Ang, Mimi Wong, Adrian Lim and John Martin Scripps are some of the most cold-blooded murderers in Singapore’s crime history. Sharon Teng revisits their horrific acts.

There are few things more heinous than a premeditated act of taking a human life. Under Singapore’s Penal Code Act (Cap. 224), culpable homicide is defined as murder when the person who causes death knowingly performs an act with the intention of causing death or with the intention of causing injury leading to death.1

In Singapore, murder is one of the few crimes that warrants the mandatory death penalty, besides drug trafficking and firearms-related offences.2 Singapore may be one of the safest countries in the world, but in spite of the city-state’s tough stance against lawbreakers and its unequivocal position on capital punishment, every now and then one hears about a horrifically violent act of crime.

In 2015, the Singapore Police Force handled a total of 33,839 crime cases (or 607 cases per 100,000 people), compared with 9,225,197 cases (or 2,870.2 cases per 100,000 people) reported in the United States during the same year. “Crimes against persons” (i.e. crimes in which the victim suffers bodily harm) constituted 12 percent. In the same year, there were 15 cases of murder, the third lowest recorded in 20 years.3

A Murderous Mind

Crimes and criminals are objects of fascination that have been fictionalised, romanticised, sensationalised, and given a larger-than-life presence in books, television and films based on whodunnit murder mysteries, forensic crime fiction, legal and courtroom dramas, psychological thrillers and police detective stories. Breaking news headlines of violent crimes, particularly those involving murder, invariably attract much public attention and invoke coffeeshop speculation and gossip.

What triggers an otherwise law-abiding citizen to go into a murderous rage and kill someone? In order to understand why people are pushed over the edge, homicide investigators, forensic psychologists, criminologists and law enforcement professionals typically examine the different elements of a homicide: whether the murder was premeditated, the motivation of the killer, the context of the killing, the choice of the murder instrument used, details of the crime scene, and the relationship between the victim and the perpetrator.

Many psychological theories have been offered to explain criminal behaviour, such as temporary insanity, mental deficiency and defective personality traits. Perpetrators of violence generally suffer from what is known as a pathological personality condition.

Criminal or offender profiling (also known as criminal investigative analysis) is sometimes used by the police to explain the behavioural makeup of the perpetrator and identify likely suspects. Careful study of the crime scene photos, the physical and non-physical evidence, the manner in which the victim was killed or the body disposed of, witnesses’ statements, autopsy photos and forensic lab reports allow investigators to compile a profile of the murderer.

The level of risk taken by the offender and the degree of organisation (or disorganisation) of the crime scene can provide clues about the relationship between the perpetrator and victim, as well as the nature of their interactions prior to the crime. Inferences can also be drawn about the perpetrator’s emotional state of mind by examining the injuries left on the victim’s body. Extensive injuries or excessive ligature markings usually point to a high level of rage or aggression. A meticulously constructed profile can become a useful tool to help the police recreate the crime scene and narrow down the scope of their investigations.

Studies have shown that many murders arise from conflicts between people who know each other, such as friends, lovers, spouses or family members. Some may resort to violence as an attempt to establish power or assert control over the other person. Other murders may be precipitated by a psychological build-up of physical or emotional trauma over time as well as anger, financial greed, sexual cravings, revenge, jealousy, fear, desperation or religious fanaticism.

Singapore has seen several prominent murder cases over the last 50 years, each unique in its own way. As there are too many cases to profile within the scope of this article, we have selected only four cases – Mimi Wong, John Martin Scripps, Sunny Ang and Adrian Lim – that span the decades from the 1960s to 1990s. The first two have been categorised as “crimes of impulse” (also called “crimes of passion”, usually driven by jealousy or murderous rage), while the latter two involved careful planning and malicious aforethought (called “instrumental crimes”, with the crime being the instrument to achieve a specific aim).

Sunny Ang: Murder for Greed

When: 27 August 1963, 5 pm

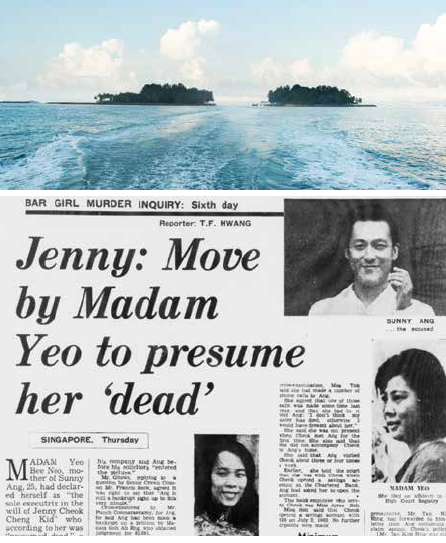

Crime scene: Straits of Pulau Dua (Sisters’ Islands)

The accused: Sunny Ang Soo Suan alias Anthony Ang, aged 28

The victim: Jenny Cheok Cheng Kid, aged 22

Sunny Ang, being led by police officers here, was charged with the murder of Jenny Cheok Cheng Kid at sea off Pulau Dua (Sisters’ Islands) on 27 August 1963. This photo is dated 4 March 1965. Source: The Straits Times © Singapore Press Holdings Limited. Permission required for reproduction.

Sunny Ang, being led by police officers here, was charged with the murder of Jenny Cheok Cheng Kid at sea off Pulau Dua (Sisters’ Islands) on 27 August 1963. This photo is dated 4 March 1965. Source: The Straits Times © Singapore Press Holdings Limited. Permission required for reproduction.“It seems there is a popular belief that there can be no murder unless a body is produced. Nothing can be more fallacious and more untrue. A person can be convicted of murder without the body being found.” 4

– Justice Murray Buttrose, the presiding High Court judge, 18 May 1965

Sunny Ang Soo Suan came from a middle-class family and obtained his Senior Cambridge Grade One school certificate in 1955. He received a Colombo Plan scholarship in 1957 to train as a commercial airline pilot, but was subsequently dropped from the programme due to his arrogant and irresponsible behaviour. Ang also had a history of theft, and was caught trying to steal from a radio shop on 12 July 1962, only to be successfully defended by the prominent criminal lawyer, David Marshall, and placed on probation.

Ang was also a former Grand Prix race car driver, and was ranked among the top 10 in the 1961 Singapore Grand Prix. He was also a reckless driver, killing a pedestrian shortly after the Grand Prix event, claiming that the man had suddenly appeared on the road. Ang became an undischarged bankrupt in October 1962; he owed debts of more than $6,000 to three parties and remained a bankrupt up to his death in 1967.

Ang met Jenny Cheok Cheng Kid when she was employed as a waitress at the Odeon Bar and Restaurant. She was a divorcee with two children, a son and a daughter. On 27 August 1963, Ang and Cheok hired a boat at Jardine Steps for a scubadiving trip to Pulau Dua (Sisters’ Islands). At Ang’s instructions, the boatman Yusuf bin Ahmad dropped anchor in the middle of the straits. Cheok suited up in her diving gear and descended into the sea, only to surface less than 10 minutes later. She then did a second dive after Ang had exchanged her cylinder tank with another, claiming that the first tank contained insufficient air. In the meantime, Ang stayed on board, claiming to have problems fixing a leak on his own tank.

When Cheok did not emerge after her second dive, Ang and Yusuf searched in vain for air bubbles breaking on the water surface before heading to nearby St John’s Island to call the Marine Police for help. Both men then picked up five Malay fisherman divers from another nearby island to help search for Cheok. Even though Ang was a good swimmer and an experienced diver, he never entered the water once to help search for Cheok.

Divers from the Royal Navy and RAF Changi Sub-Aqua Club conducted several searches for Cheok’s body to no avail. Then, during a search operation on 3 September, a flipper was found on the ocean floor at a depth of 45 feet, near the spot where Cheok was last seen. The flipper’s strap was found with clean cuts, which could only have been done with a razor blade, a knife or a pair of scissors. Laboratory tests later confirmed that the cuts were unlikely to have been caused by corals. The flipper was identified as one of a pair which Ang’s younger brother, William, had borrowed from his classmate, David Benjamin Woodworth. The prosecution concluded that it was one of the flippers worn by Cheok during her fateful dive.

According to an expert witness, the sudden loss of a flipper would adversely affect a diver’s stability and mobility underwater. Other witnesses called to the stand testified that the waters surrounding Sisters’ Islands had a strong undertow, and were considered challenging even for experienced divers; in fact the area was regarded as an unsuitable site for swimming, let alone scuba-diving. Cheok’s half-sister, Irene Toh, and the boatman, Yusuf, both corroborated that Cheok was a poor swimmer and a novice scuba diver. At the time of her disappearance at 5 pm on 27 August 1963, there was a strong current running along the Pulau Dua straits. Ang had deliberately scheduled the dive trip on Tuesday − a workday afternoon when it was unlikely for people to be in the vicinity.

About a month before Cheok’s disappearance, Ang had signed up his girlfriend for four accident insurance policies totalling $350,000 from two insurance companies: Edward Lumley and Sons (M) Ltd, and American International Underwriters Ltd. On 14 August, Ang insured Cheok for a further $100,000 accident coverage with the Insurance Company of North America. And barely three hours before their dive trip on 27 August, Ang extended the policy for a $150,000 protection to cover an additional five days starting from 11 am on that day.

Three days after Cheok’s disappearance, Ang informed Edward Lumley and Sons that Cheok had been in a “tragic accident”. On 14 October, Edward Lumley received a lawyer’s letter informing them that Ang’s mother, Madam Yeo Bee Neo, was the sole executor of Cheok’s will. Ang also made efforts to hasten the coroner’s inquiry into Cheok’s disappearance and seemed to be in a great hurry to have her death confirmed for the purpose of claiming against her insurance policies.

(Top) The straits of Pulau Dua (Sisters’ Islands) where Jenny Cheok Cheng Kid was murdered at around 5 pm on 27 August 1963. Photo taken by Ria Tan in August 2008. Courtesy of WildSingapore.

(Top) The straits of Pulau Dua (Sisters’ Islands) where Jenny Cheok Cheng Kid was murdered at around 5 pm on 27 August 1963. Photo taken by Ria Tan in August 2008. Courtesy of WildSingapore.(Above) Sunny Ang and his mother Madam Yeo Bee Neo (who was sole executor of the deceased’s will) tried to hasten the coroner’s inquiry into concluding that Jenny Cheok had drowned so that an insurance claim could be filed. The Straits Times, 5 March 1965, p.11.

Ang was arrested on 21 December 1964 and initially charged with Cheok’s murder the following day, but was given a discharge not amounting to an acquittal on 30 December after his lawyer, Punch Coomaraswamy, argued that Ang should not be kept in remand while waiting for the prosecution to set a date for the preliminary hearing. About an hour after his discharge, however, Ang was again charged for the same offence and remanded in Outram Prison.

Ang was tried in High Court before Justice Murray Buttrose and a seven-man jury. The prosecution was led by Senior Crown Counsel Francis Seow and assisted by Syed Alwee bin Ahmad. On the second day of the trial on 27 April 1965, the court was informed that Cheok had made a will in the presence of Ang on 7 August 1963 and had appointed Ang’s mother, Madam Yeo, as the sole beneficiary. This was bizarre as Cheok had never met Madam Yeo, according to Cheok’s half-sister, Irene.

In the prosecution’s summation of the case on 18 May 1965, Ang was alleged to have murdered Cheok by tampering with her diving equipment, causing her to drown. His motive was clear: to collect the huge payouts from insurance policies he had taken out on Cheok less than a month before her death.

After an intense 13-day trial, the seven-men jury deliberated for two hours and returned with a unanimous guilty verdict. Ang was sentenced to death on 18 May 1965 and hanged at 5.55 am on 7 February 1967.

The Sunny Ang murder case was the first tried in Singapore and Malaysia that was based entirely on circumstantial evidence, as the victim’s body was never found and there were no witnesses to the crime. Ang was also one of the last murderers to be tried by jury in Singapore − before jury trials were abolished in 1969.

In 1979, Harvesters Film Distribution and Production Pte Ltd announced that the Sunny Ang murder was slated to be made into a Mandarin film estimated to cost $700,000. The actual names of the key people involved in the case would be changed to avoid any legalities. The case was also featured in an episode of the 13-part True Files, a docudrama produced by Mediacorp that reenacted high profile crimes of the last five decades, and telecast on 6 June 2002.

Mimi Wong: A Jealous Lover

When: 6 January 1970, 9.30 pm

Crime scene: Bathroom of a Jalan Sea View semi-detached house

The accused: Wong Weng Siu alias Mimi Wong, aged 34, and her husband, Sim Woh Kum alias Sim Wor Kum, aged 40

The victim: Ayako Watanabe, aged 33

By the time Mimi Wong was 14, she was already working as a packer at a factory in Neil Road. She met Sim Woh Kum, then 17 years old and a factory worker, at a picnic and they soon became a couple.

Wong and Sim got married in 1958 when she was only 19. Raised by her stepmother, Wong had been bullied and beaten as a young girl, but after her marriage, she became the aggressive party: she was reported to have physically abused her husband and her mother-in-law on several occasions.

After Sim lost his job, Wong became the sole breadwinner, supporting her husband and two sons. In 1967, she started a new job as a towel girl at a Pasir Panjang Road bar and became a waitress soon after. She later worked as a bargirl, supplementing her income as a hostess and social escort at night.

In 1966, Japanese mechanical engineer Hiroshi Watanabe was posted to Singapore for work. He met Wong in October that year when she was working as a bargirl at the Flamingo Nightclub at Kim Seng Road. They became intimate soon after and Wong became Hiroshi’s mistress in mid-1969, by which time she had been separated from her husband. Wong and Hiroshi first stayed in a rented room in Alexandra Road before moving to a house in Everitt Road.

In September 1969, Hiroshi informed Wong that his wife, Ayako, and their three children would be joining him in Singapore. Wong was enraged by this and threatened to harm his family. Hiroshi’s family arrived on 23 December 1969 and moved into a house in Jalan Sea View. The next day, Hiroshi told Ayako about his relationship with Wong. He even took his wife and children to meet Wong on Christmas Day. Wong became extremely agitated as she feared that Hiroshi would put an end to their relationship now that his family was here. Indeed, Hiroshi had told his wife that he was making efforts to distance himself from Wong but was forced to proceed with caution due to Wong’s fiery temper.

Wong decided to hatch a plan with her estranged husband, asking him to help in her plot to murder Ayako. Four days before the deed, Wong got together a tin of toilet cleaning liquid, a knife and a pair of black gloves. At 9.30 pm on the night of 6 January 1970, Wong and Sim went to the Jalan Sea View house. Sim pretended to be a workman who had come to repair a broken bathroom basin. When all three were standing near the bathroom on the second storey, Sim threw the cleaning liquid into Ayako’s eyes, temporarily blinding her. Wong then stabbed Ayako repeatedly with the knife and fled the scene with Sim.

When Hiroshi returned home at 10.30 pm after his night shift, he discovered his slain wife lying in a pool of blood in the bathroom, with his three children crying outside. According to his nine-year-old daughter, Chieko, their mother was attacked by Wong and an unknown man. Chieko had witnessed Sim and Wong manhandling her mother while she was on the bathroom floor, with blood drenching her chest.

Ayako was found to have a total of nine wounds: one on the right side of her neck that had severed the jugular vein, and another in her stomach that had pierced her aorta. Ayako also suffered defensive wounds on her right hand, with finger cuts indicating that she had fought off her assailant.

Sim and Wong were arrested on 7 and 8 January 1970 respectively after they were singled out by Chieko at an identification parade. Their joint trial, which began on 2 November the same year, was presided by Justice Tan Ah Tah and Justice Choor Singh. N. C. Goho and John Tan Chor-Yong were assigned by the Supreme Court as Wong’s and Sim’s defence lawyers respectively. Then Solicitor-General Francis Seow was the lead prosecutor.

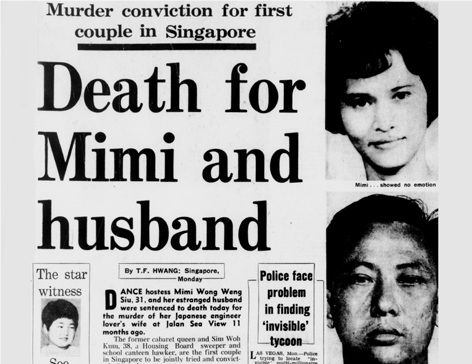

Mimi Wong and her husband Sim Woh Kum were sentenced to death on 7 December 1970 for the murder of Ayako Watanabe. Wong was the mistress of the Japanese woman’s husband. The Straits Times, 8 December 1970, p.

Mimi Wong and her husband Sim Woh Kum were sentenced to death on 7 December 1970 for the murder of Ayako Watanabe. Wong was the mistress of the Japanese woman’s husband. The Straits Times, 8 December 1970, p.During the trial, Wong pushed the blame entirely on Sim for Ayako’s murder, confessing only to slapping and shoving the victim but not stabbing her. Sim was vehement in his protest that it was Wong who had masterminded the entire heinous plot and stabbed the victim repeatedly. After a marathon 26-day trial, both Wong and Sim were convicted of killing Ayako, and sentenced to death on 7 December 1970.

The pair made three rounds of appeals between 1972 and 1973 to have their death sentences commuted to life imprisonment, but were unsuccessful. The couple was hanged at dawn on 27 July 1973 at Changi Prison, after a 32-month stay of execution. Wong became the first woman to be sentenced to death in post-Independence Singapore. Wong and Sim were also the first couple in Singapore to be jointly executed for murder.

The Mimi Wong murder case has been featured in three books on true Singapore crimes: Sisters in Crime (1992) by journalist Sumiko Tan; Murder is My Business: Medical Investigations into Crime (1999), a book co-written by the late forensic pathologist, Chao Tze Cheng and former journalist Audrey Perera; and Guilty as Charged: 25 Crimes That Have Shaken Singapore Since 1965 (2015).

The case was also featured in episode two of True Files, which was shown on Channel 5 on 30 April 2002.

Adrian Lim: The Ritual Child Murders

When: 25 January 1981 (Agnes’ murder) and 6 February 1981 (Ghazali’s murder)

Crime scene: A seventh-storey flat in Block 12, Toa Payoh Lorong 7

The accused: Adrian Lim, aged 46; Catherine Tan Mui Choo, aged 32; Hoe Kah Hong, aged 33

The victims: Agnes Ng Siew Heok, aged 9; Ghazali bin Marzuki, aged 10

The Adrian Lim murder case is considered one of Singapore’s most infamous and abominable, involving three cold-blooded killers, bizarre occult practices, blood sacrifices, sexual perversion, electric shock torture, consumption of human and animal blood as well as the ritual killings of two children.

Adrian Lim was the eldest son from a middle-class family. A divorced father of two, he was a self-proclaimed medium who had developed a deep interest in the occult since his teenage years. Lim also read extensively on Hinduism, Buddhism and Christianity. Over time, he became the consummate confidence trickster, preying on desperate, emotionally troubled and gullible women seeking help − in return for money and sex.

Catherine Tan Mui Choo, then 18 years old, was a bargirl working at Champagne Bar in Anson Road when she met Lim. Depressed over family problems, Tan had initially sought Lim’s help in reading her fortune. They soon developed an intimate relationship, with Tan supporting her boyfriend with her earnings from prostitution and from her night job as a lounge hostess.

Between 1976 and 1978, Lim and Tan got together to perform risqué striptease acts at various nightclubs in Singapore, Kuala Lumpur, Ipoh and Penang. Tan married Adrian on 11 June 1977, his first wife having divorced him a year earlier. Their relationship both before and after marriage was an unhappy one, with Tan having to endure frequent beatings, electric shock treatments and the indignity of her husband’s promiscuity.

Into this relationship entered a third party: Hoe Kah Hong. She came from an impoverished family and had been illtreated by her own family while growing up. Hoe met Lim in 1979 while accompanying her mother and sister for a consultation. Deluded by Lim’s lies that she was possessed by evil spirits, Hoe ended up as one of his “holy” wives5 even though she was already married, and went to live with Lim and Tan in their Toa Payoh flat.

On 7 January 1980, Lim lured Hoe’s husband, Benson Low Ngak Hua, to his flat and electrocuted him to death, casting the blame on an evil spirit residing in Hoe. Depressed after her husband’s death, Hoe began hearing voices and hallucinating, and soon developed suicidal tendencies; she was later diagnosed as suffering from schizophrenia. Hoe also endured physical assaults from both Lim and Tan, including electric shock treatments.

On 7 November 1980, Lim was accused of raping a part-time cosmetics salesgirl and beautician, Lucy Lau Kok Huat. He was arrested, only to be later released on bail. Furious at being called up for investigation by the police and asked to report fortnightly to the Toa Payoh Police Station to extend his bail, Lim decided to kill innocent children out of revenge. His motive (or so he claimed) was to confuse the police and divert their attention from the rape allegation.

His first victim was Agnes Ng Siew Heok, a Primary Three student and the youngest in a family of nine children. Her body was found in a luggage left on the ground floor lift landing at Block 11, Toa Payoh Lorong 7, on 25 January 1981. The autopsy report later revealed that she had been sexually assaulted before being suffocated.

The next victim was Ghazali bin Marzuki, a Primary Four student and the eldest in a family of three children. On 7 February 1981, his body was discovered under a tree located between blocks 10 and 11 of Toa Payoh Lorong 7. He had died from drowning. This time, the police found drops of blood leading to Lim’s seven-storey flat in Block 12, with more blood discovered inside the flat. Tests later confirmed that the blood was of human origin.

Inside the flat, the police found other incriminating evidence: pieces of paper with the children’s names and telephone numbers, strands of hair, books on witchcraft, newspaper clippings of human sacrifice, and bloodstained Hindu idols. Traces of blood (the same as Ghazali’s blood group) were also found on Lim’s shorts and handkerchief. The trio were arrested on 7 February 1981 and taken to CID headquarters for questioning. Under interrogation, Tan was the first to confess, followed by Lim and Hoe. They were charged in court with the murders of the two children within 24 hours of their arrest.

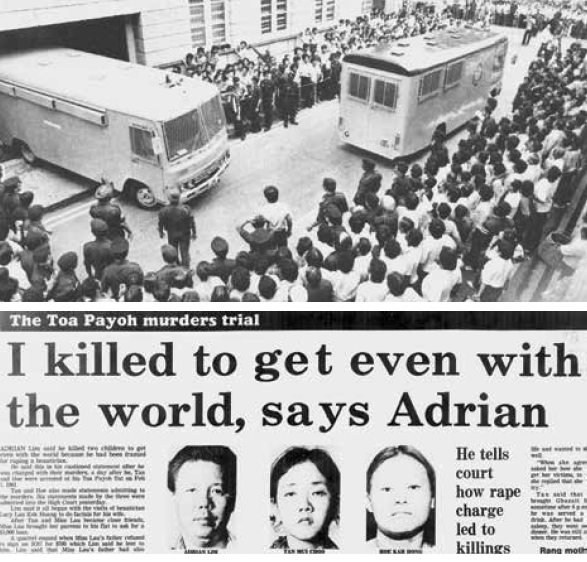

(Top) Crowds outside the High Court during Adrian Lim’s 42-day trial. All rights reserved, Kutty, N. G. (1989). Adrian Lim’s Beastly Killings (p. 151). Singapore: Aequitas Management Consultants. (Call no.: RCLOS 364.1523095957 KUT).

(Top) Crowds outside the High Court during Adrian Lim’s 42-day trial. All rights reserved, Kutty, N. G. (1989). Adrian Lim’s Beastly Killings (p. 151). Singapore: Aequitas Management Consultants. (Call no.: RCLOS 364.1523095957 KUT).(Above) Adrian Lim claimed to have murdered two innocent children, Agnes Ng Siew Heok and Ghazali bin Marzuki, out of revenge for being accused of raping cosmetics salesgirl Lucy Lau Kok Huat. It was a flimsy excuse that made no sense, and was thrown out in court. The Straits Times, 5 April 1983, p. 12.

Lim and Tan were also charged with the murder of Hoe’s husband. The defence’s argument of diminished responsibility was rejected by both presiding judges, Justice Sinnathuray and Justice F. A. Chua. At the end of a lengthy trial that began on 27 March 1983, the trio were sentenced to death two months later on 25 May. Lim declined to appeal against his sentencing. Tan’s and Hoe’s three separate appeals were dismissed as they were deemed mentally sound at the time of the killings.

All three were hanged at dawn on 25 November 1988, and their bodies cremated at Mount Vernon Crematorium.

The shocking nature of the crime and the ensuing media reports saw hordes of Singaporeans packing the courtroom, beginning with the preliminary inquiry in September 1981 and throughout the trial held two years later in 1983. On verdict day, the crowds spilled over from the courtroom to the surroundings of the Supreme Court, requiring the police to cordon off the area. Cheers rang out when the verdict was announced. The trial, lasting a total of 41 days, was the second longest in Singapore.6

The Adrian Lim case received extensive coverage in print, with four books on the subject. Publishers raced to be the first to publish a book on the bizarre murders and two of them, Unholy Trinity by Alan John, and Adrian Lim’s Beastly Killings by N. G. Kutty, were published within two months of the hanging. Two other books, I Confess, and the sequel, Was Adrian Lim Mad?, both by Sit Yin Fong, followed soon after. The story also merited inclusion in a 2013 book compilation of the most vicious murders in Singapore by Yeo Suan Futt titled Murder Most Foul: Strangled, Poisoned and Dismembered in Singapore.

Adrian Lim’s Beastly Killings by N.G. Kutty and Unholy Trinity by Alan John were published within two months of the hangings of the murderers. All rights reserved, Aequitas Management Consultants, 1989, and Times Books International, 1989.

Adrian Lim’s Beastly Killings by N.G. Kutty and Unholy Trinity by Alan John were published within two months of the hangings of the murderers. All rights reserved, Aequitas Management Consultants, 1989, and Times Books International, 1989.The case inspired two films: Medium Rare and God or Dog. Loosely based on the Adrian Lim ritual murders, Medium Rare was Singapore’s first full-length English-language film, and premiered in local theatres on 28 November 1991. A commercial flop, the movie received scathing reviews for its weak script, slow pacing and unprofessional editing. God or Dog first premiered at the 1997 Singapore International Film Festival before it was screened in local cinemas. The film was roundly criticised for its scenes of gratuitous sex and nudity.

John Martin Scripps: The Body Parts Murderer

When: Between noon, 8 March, and 8 am, 9 March 1995

Crime scene: A room in River View Hotel (now renamed Four Points by Sheraton, Riverview)

The accused: John Martin Scripps, aged 35

The victim: Gerard George Lowe, aged 33

Born in England as John Martin Scripps, the Englishman legally changed his name to John Martin when he was in his 20s. Scripps had had many run-ins with the law as a teenager. His criminal resume included more than 20 counts of burglary, two cases of resisting arrest and one count of outrage of modesty. He had also been arrested twice for drug smuggling, in 1987 and 1992, but had escaped while on parole from prison.

In October 1994, Scripps was wanted for questioning after a dismembered body of a male homosexual was found in a rubbish bin in San Francisco. A month later, he became a murder suspect in Mexico City when a British tourist, Tim McDowell, aged 28, was found dead.

Scripps arrived in Singapore on 8 March 1995 using a passport belonging to a Simon James Davis. At Changi Airport, he met South African tourist George Gerard Lowe. Both agreed to share a hotel room to save costs. Shortly after checking into a room at River View Hotel, Scripps clubbed Lowe over the head with a 1.5-kg hammer and within an hour, had dismembered his head, torso, arms, thighs and legs in the bathtub. The body parts were tied up in trash bags, packed in Lowe’s suitcase and a smaller bag, and placed in the wardrobe.

Scripps then went on a two-day shopping spree using Lowe’s money and credit card. Prior to checking out of the hotel on 11 March, Scripps dumped the contents of the suitcase into the Singapore River. The contents of the other bag were also disposed of before being abandoned at the Thomas Cook office in Anson Road. The bag was left empty save for a bottle of Lynx deodorant used to cover up the smell of rotting flesh. He then flew to Bangkok on 11 March.

On 13 March, a black plastic trash bag containing severed legs was found near Clifford Pier by a boatman. The torso and thighs were found three days later, also in plastic bags. The head and arms never surfaced. The torso and legs were positively identified by Lowe’s wife and DNA tests confirmed his identity.

Police were aided in their investigations by a missing person report from South Africa. Once Lowe’s identity was ascertained, the police were able to trace Scripps’ activities between 8 and 11 March, using hotel and credit card transaction records. Traces of blood were also found on the wall tiles, the door and on the underside of the toilet bowl in the bathroom of the room where the murder took place.

Meanwhile, between 19 and 24 March, the dismembered body parts of Canadian tourists, school teacher Sheila Damud and her son Darin, were discovered in Phuket. They had checked in at the same hotel in Phuket as Scripps did on 15 March. Scripps was arrested at Changi Airport on 19 March when he returned to Singapore. On 24 March he was charged with the murder of Gerard George Lowe.

During Scripps’ arrest, knives, a hammer, an electrical stun device, handcuffs and six passports were found in his possession – Lowe’s, one with the name “John Martin”, two bearing the name “Simon James Davis” and the two belonging to the Canadian tourists in Phuket. The two flick knives with jagged edges, according to senior forensic pathologist, Chao Tzee Cheng, and experienced prison butcher, James Quigley, were “sufficient to dismember Mr Lowe’s body”.7 The personal belongings of the Canadians and Lowe were also recovered.

During the court trial, it was revealed that Scripps had learned butchering skills while serving out a six-year prison sentence for drug trafficking, and was put in charge of the prison butchery until he was transferred to another prison. In his defence, Scripps confessed that he had unintentionally killed Lowe by bludgeoning his head with a hammer during a heated argument, but maintained his claim to the end that a British friend had disposed of Lowe’s body.

At the end of the 17-day trial on 10 November 1995, Scripps was pronounced guilty of murdering and dismembering Lowe, and sentenced to death.

He filed an appeal against his conviction on 13 November but gave up his right to appeal on 8 January 1996. He also declined to file a clemency plea with then President Ong Teng Cheong. On 15 April 1996, Scripps’ date of execution was announced by the British Foreign Office – he was the first Briton to be convicted of murder and sentenced to death in Singapore − and he was hanged at Changi Prison at 6 am on 19 April 1996.

The police took just 11 days to solve the case from the date of Lowe’s murder.

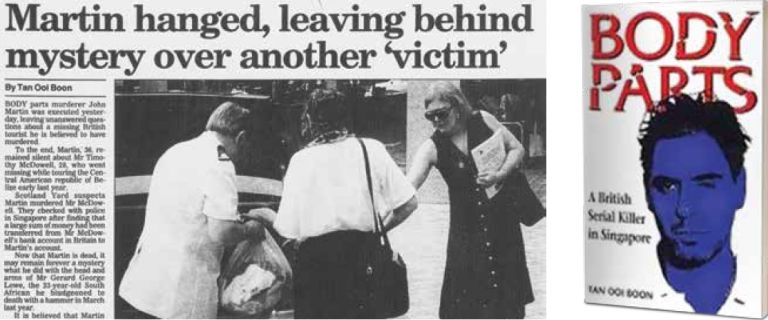

The murder case was documented in the book Body Parts: A British Serial Killer in Singapore (1996). Written by Tan Ooi Boon, the crime reporter with The Straits Times who first uncovered Scripps’ shocking murders in March 1995, the book delves into the psyche of the monster who had cold-bloodedly killed and dismembered his victims.

(Left) The British national John Martin Scripps was hanged at Changi Prison on 19 April 1996, 408 days after killing Gerard Michael Lowe, a South African tourist whom he met in Singapore. The Straits Times, 20 April 1996, p.25.

(Left) The British national John Martin Scripps was hanged at Changi Prison on 19 April 1996, 408 days after killing Gerard Michael Lowe, a South African tourist whom he met in Singapore. The Straits Times, 20 April 1996, p.25. (Right) The John Martin Scripps murder case was documented in a book by crime reporter Tan Ooi Boon. All rights reserved, Tan, O. B. (1996). Body Parts: A British Serial Killer in Singapore. Singapore: Times Books International. (Call no.: RSING 364.1523095957 TAN).

Other Notable Murder Cases

Many more murders exist in Singapore’s crime annals beyond the four murders highlighted in this article. Some of these include:

-

Lim Ban Lin’s killing of a police officer in 1968. He became the most wanted criminal in Singapore and Malaysia, and was gunned down in 1972.

-

The “tontine killing” in 1974 where a 44-year-old housewife, Sim Joo Keow, killed and dismembered her 53-year-old sister-in-law, Kwek Lee Eng, over money owed by the former. The dismembered body parts were uncovered in three locations: in a disused toilet at Aljunied Road, along the banks of the Kallang River, and in Sim’s house in Jalan Besar.

-

The slaughter of the four children from the Tan family in 1979, all of whom were under the age of 10. Dubbed the Geylang Bahru murder, the case remains unsolved to this day.

-

The 1983 Andrew Road murders committed by Sek Kim Wah, who had killed five people during robbery attempts.

-

The 1984 “curry murder” where Ayakanno Marimuthu, 38, was clubbed to death, chopped up, cooked in curry and dumped in roadside dustbins. His alleged murderers were his wife and her relatives. All six suspects were charged with murder in March 1987, but were later given a discharge not amounting to an acquittal due to lack of evidence.

-

The killing and dismemberment of 22-year-old Chinese national Liu Hong Mei by her 50 year-old married lover and supervisor, Leong Siew Chor, to hide the theft of an ATM card. The 2005 murder came to light when parts of her body surfaced at the Kallang River. The crime became known as the Kallang body parts murder.

-

The 2005 Orchard Road body parts murder in which 29-year-old Filipino maid Guen Garlejo Aguilar killed and dismembered her best friend, 26-year-old Jane Parangan La Puebla, over a money dispute. The dismembered body parts were subsequently dumped near the Orchard MRT station and at a bus stop along Lornie Road.

-

The killing of two-year-old Nonoi in 2006 by her stepfather, Mohammed Ali Johari, who had repeatedly dunked her in a pail of water to stop her from crying.

-

The Yishun triple murder by a Chinese national, who had savagely stabbed his lover, her daughter and their flatmate multiple times over money woes in 2008.

To read up on these cases and others, please refer to the books listed below at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library at the National Library Building and branches of public libraries.

Sharon Teng is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. Her responsibilities include managing the library’s social sciences and humanities collection, developing content, and providing reference and research services.

Sharon Teng is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. Her responsibilities include managing the library’s social sciences and humanities collection, developing content, and providing reference and research services.

REFERENCES

Campbell, J. H., & DeNevi, D. (2004). Profilers: Leading investigators take you inside the criminal mind. Amherst, N.Y.: Prometheus Books. (Call no.: R 363.25 PRO)

Holmes, R. M., & Holmes, S. T. (1996). Profiling violent crimes: An investigative tool. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. (Call no.: R 363.25 HOL)

Stone, M. (2009). The anatomy of evil. Amherst, N.Y.: Prometheus Books. (Call no.: R 364.3 STO)

Sunny Ang

Bargirl’s last dive – boatman. (1965, May 6). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Chia, P., Sam, J., & Hwang, T. F. (1965, May 19). Judge: These links in the chain bind the accused tightly. The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Chia, P., Sam, J., & Hwang, T. F. (1965, May 19). First of the 16 links: ‘A powerful motive…’ The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Discharged man re-arrested on murder charge. (1964, December 31). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Hwang, T. F. (1965, March 5). Jenny: Move by Madam Yeo to presume her ‘dead’. The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Josey, A. (2009). Cold-blooded murders. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions. (Call no.: RSING 345.595702523 JOS)

Page 36 miscellaneous column 1. (2002, June 6). Today, p. 36. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

She is dead and it was murder to get $400,000, jury told. (1965, May 18). The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Skin-dive bar girl: Murder probe now. (1963, September 6). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Sunny Ang in the dock in Twin Sisters case. (1965, April 27). The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Sunny Ang was there when Cheok made out her will, says witness. (1965, April 28). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Sunny found guilty, to hang. (1965, May 19). The Straits Times, p.1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

That flipper – by man flown from England. (1965, May 8). The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Mimi Wong

Davidson, B. (1973, July 24). Sheares rejects Mimi’s plea for mercy. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Hwang, T. F. (1970, November 4). Nightclub waitress on murder trial collapses. The Straits Times, p. 15. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Hwang, T. F. (1970, December 8). Death for Mimi and her husband. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Hwang, T. F. (1972, July 23). Appeal of Mimi Wong and her husband (both under death sentence) is dismissed. The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Elengovan. (1970, November 7). ‘She cried out to me she wanted to die’. The Singapore Herald, p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

‘I heard Mother screaming in pain’. (1970, November 6). The Singapore Herald, p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Latest. (1973, March 16). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Mimi and husband go to the gallows. (1973, July 28). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Mimi struck Mrs. W with ‘glimmering object’ says husband. (1970, November 27). The Straits Times, p. 19. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

‘Mimi was of sound mind on day of killing’. (1970, December 3). The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Mimi Wong’s execution was a grim ‘first’. (1979, December 23). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Mimi’s hubby refused leave to appeal. (1973, February 2). New Nation, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Seah, L. (2002, May 6). Chilling, but little bite. The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Singh, P. (1978, February 26). The quadrangle of love – and death. The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Chao, T. Z. (1990, September 5). Solving bathroom murder. The New Paper, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Star witness Chieko proved the killing: Seow. (1970, December 8). The Straits Times, p. 17. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Wee, B. H., & Mohan, B. (1973, July 27). Mimi Wong and husband hanged. New Nation, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Adrian Lim

Adrian Lim book sets sales record. (1989, June 22). The New Paper, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Adrian Lim story to be basis of $1.7 m film. (1990, November 14). The Straits Times, p. 30. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Davidson, B. & Chua, M. (1983, April 5). I killed to get even with the world. The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

But it’s one small step forward. (1991, November 30). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Chia, H. (1989, March 15). Murder. They wrote. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Goh, J. (1991, April 13). Singapore’s first English feature film hits snags. The Straits Times, p. 22. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Goh, J. (1991, November 25). Medium Rare – high on local colour, low on suspense. The Straits Times, p. 24. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Infocomm Media Development Authority. (2015, March). List of Singapore movies (1991–2016). Retrieved April 1, 2017 from Info-communications Media Development Authority website.

John, A. (2016). Unholy trinity: The Adrian Lim ‘ritual’ child killings. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions. (Call no.: RSING 364.1523095957 JOH)

Kerk, C. (1997, April 26). Adrian Lim revisited. The Business Times, p. 20. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Kutty, N. G. (1989). Adrian Lim’s beastly killings. Singapore: Aequitas Management Consultants. (Call no.: RCLOS 364.1523095957 KUT)

Sit, Y. F. (1989). I confess. Singapore: Heinemann Asia. (Call no.: RSING 364.1523095957 SIT)

Sit, Y. F. (1989). Was Adrian Lim mad? Singapore: Heinemann Asia. (Call no.: RSING 345.5957067 SIT)

Tan, S. (1997, March 21). 3 homegrown films to be screened commercially. The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Yeo, S. F. (2013). Murder most foul: Strangled, poisoned and dismembered in Singapore (pp. 115–126). Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions. (Call no.: RSING 364.1523095957 YEO)

John Martin Scripps

Body in bag picked up from sea off Clifford Pier. (1995, April 2). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Body parts: Anatomy of a killing. (1995, November 12). The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Grisly finds near the pier. (1995, April 5). The New Paper, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Guilty as charged: John Martin Scripps befriended tourists, then butchered them. (2016, May 16). The Straits Times. Retrieved from Factiva via NLB’s eResources website.

Lim, Y. (1995, March 30). Second time on the run. The New Paper, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Martin files appeal against conviction. (1995, November 17). The Straits Times, p. 41. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Miller, B. (1995, November 11). Martin’s last ‘Hello’ then off to date with death. The New Paper, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Tan, O. B. (1996, March 10). ‘Body parts’ murderer will not petition for presidential pardon. The Straits Times, p. 29. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Tan, O. B. (1995, March 30). Accused in South African murder case jailed for drug possession in London. The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Tan, O. B. (1995, October 5). Martin: I hit Lowe, but friend disposed of body. The Straits Times, p. 37. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Tan, O. B. (1996, April 20). Martin hanged, leaving behind mystery over another ‘victim’. The Straits Times, p. 25. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Wanted in 3 continents… (1995, March 30). The New Paper, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

What his mum says. (1995, November 13). The New Paper, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Who is John Martin? (1995, November 12). The Straits Times, p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

NOTES

-

Singapore. The statutes of the Republic of Singapore. (2008 Rev. ed.). Penal Code Act (Cap. 224, p. 124). Singapore: (s.n.). (Call no.: RCLOS 348.5957 SIN) ↩

-

Yong, C. (2016, December 9). Most S’poreans support death penalty, but less so for certain cases: Survey. The Straits Times. Retrieved from Factiva via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Singapore Police Force. (2016, September). Annual crime brief 2015. (pp. 1, 5). Retrieved from Singapore Police Force website; Singapore Police Force. (2015). Singapore Police Force Annual 2015 (pp. 83–84). Retrieved from Singapore Police Force website; Nokman, F. S. (2016, December 20). Crime index goes down, but perception of safety remains low. Retrieved from New Straits Times website; United States crime rates 1960 – 2015. (2015). Retrieved from Disaster Center website. ↩

-

Chia, P., & Sam, J. (1965, May 18). Jury told: Dismiss this fallacy completely from your minds. The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

In court, Adrian revealed that he had up to as many as 40 “holy wives” whom he had married in front of the altar at his flat, with the altar idols as the only witnesses to the matrimonial ceremony. ↩

-

The 62-day Pulau Senang trial in 1963 holds the record for being the longest trial in Singapore. Eighteen among the 59 criminals charged were convicted of rioting and arson at the experimental island penal colony and sentenced to be hanged. ↩

-

Yaw, Y. C. (1995, October 4). ‘This is a perfect instrument for deboning’. The New Paper, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG ↩