Tales of the Malay World: Manuscripts and Early Books

Literary works in the ancient Malay-speaking world were not enjoyed silently but read aloud to an audience, as Tan Huism tells us in this latest exhibition by the National Library.

“That night the war-chiefs and the young nobles were waiting in the hall of audience, and the young nobles said, ‘Why do we sit here idly? It would be well for us to read a tale of war that we may profit from it.. … ‘Take this message to the Ruler, that all of us crave from him the Story of Muhammad Hanafiah, in the hope that we may obtain profit from it, for the Franks are attacking tomorrow’”.1

– Sejarah Melayu, translated by Charles C. Brown

“Maka hari pun malam-lah, maka segala hulubalang dan segala anak tuan2 semua-nya bertunggu di-balairong. Maka kata segala anak tuan2 itu, ‘Apa kita buat bertunggu di balairong diam2 sahaja? Baik kita membaca hikayat perang, supaya kita beroleh faedah daripadanya.’ … ‘Pergi memohonkan Hikayat Muhammad Hanafiah, sembahkan mudah-mudahan dapat patek2 itu mengambil faedah daripada-nya, kerana Feringgi akan melanggar esok hari’”.2

– Sejarah Melayu, edited by William G. Shellabear

For many of us, the idea of reading a book is a solitary affair –we all read silently, as one is often reminded in libraries. Except of course when we read a story to a child, or when an author reads an excerpt of his or her work at a public reading.

While reading silently is the accepted norm today, this was not necessarily the case in the Malay-speaking world before the 20th century. There are numerous descriptions in old Malay manuscripts that describe the practice of reading literary works out aloud to an audience. The consumption of literature back then was a largely communal affair.

“Tales of the Malay World: Manuscripts and Early Books” is the National Library’s latest exhibition, to be launched on 18 August 2017 at the National Library Building on Victoria Street. The exhibition will showcase a selection of old Malay manuscripts and early printed books from the 18th to the early 20th centuries. The materials come from the National Library’s Rare Material Collections as well as institutions in the United Kingdom and Netherlands, and museums in Singapore. The oldest item in the exhibition is a manuscript of the Syair Perang Mengkasar (Poem of the Makassar War), which was copied around 1710 in Ambon.

The Age of Malay Manuscripts

For centuries, Malay functioned as a language of trade and diplomacy in the cosmopolitan trading centres of maritime Southeast Asia. Malay was also the literary language of the region. What has survived today from these literary traditions are texts derived from manuscripts written in Jawi (Malay written in a modified Arabic script). Aside from religious texts, there are court chronicles, narratives that recount fantastic adventures (hikayat) of kings and heroes as well as romantic poetry (syair). These tales provide a glimpse of the society during which these writings were produced and read.

Various scholars have tried to estimate the number of Malay manuscripts in libraries around the world, and have put the figure at around 10,000.3 The tropical climate of the region has had detrimental effects over the years on these paper-based materials, but even so, 10,000 is a small number – an indication perhaps of the relatively small output of Malay manuscripts in the first place.

This scarcity of manuscripts was noted during the early 19th century. Abdul Kadir and his son, Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir, the accomplished Malay scholar better known as Munsyi Abdullah (1797[?]–1854), both found it extremely difficult to procure manuscripts for Europeans who wanted to learn more about the language and region. The dearth of such manuscripts is partially attributed to the manner in which these texts were used; most manuscripts were held in the royal courts, in the hands of feudal elites or storytellers. Furthermore, perhaps because literary texts were meant to be performed for an audience, there was less of a need for stories to be written down.4

European officials and scholars of the late 18th and early 19th centuries collected Malay manuscripts in earnest in their attempts to learn the language and understand the culture in order to control and administer the region. This in turn created a commercial market for Malay manuscripts, some of which eventually found new homes in libraries in UK and Europe. The exhibition provides a unique opportunity for visitors to view rare manuscripts that have been borrowed from the British Library and Royal Asiatic Society in the UK and the Leiden University Library in the Netherlands and shown in Singapore for the first time.

Starting from the mid-19th century onwards, the Malay manuscript tradition was impacted by the appearance of a fledgling Muslim5 printing scene in Singapore. By the late 19th century, Singapore had become the leading centre for the printing of Malay and Muslim books in Southeast Asia.

The first printers used a method of printing known as lithography to reproduce the physical characteristics of a handwritten manuscript cheaply and in large quantities. These early printed hikayat and syair were even used in a similar way as their original handwritten counterparts, ie recited and sung for an audience. Nevertheless, over time, the advent of printing and other societal changes, such as the introduction of the Western school system, were to affect the ways in which people traditionally interacted with the written text – effectively spelling the end of the manuscript tradition.

The impact of printing and the development of the early Malay/Muslim printing scene in Singapore will be explored in the exhibition. To emphasise the importance of the oral and aural aspects of traditional Malay written literature,6 visitors will also be able to hear the recitation of a hikayat (or narrative prose) upon entering the exhibition space. In addition, there will be opportunities to encounter literary works that continue to capture the public’s imagination to this day, such as the Sejarah Melayu (Malay Annals), Hikayat Hang Tuah and folk tales featuring the wily mousedeer (sang kanchil).

EXHIBITION HIGHLIGHTS

A syair is a narrative poem that rhymes. This was a popular literary genre in the Malay world from the end of the 18th century, and was one of the most popular forms of literature published by early Malay/Muslim presses well into the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The origins of the syair form, however, are unclear. This romantic poem, the Syair Ken Tambuhan, tells the tragic love story of Princess Ken Tambuhan and Prince Kertapati, based on the popular Panji tales7 from Java. This particular syair has been hailed by 19th-century European scholars as a work of literary merit. The vivid descriptions in Syair Ken Tambuhan were intended by the author to evoke feelings of compassion and sympathy for the heroine. Romantic syair were dismissed by some early Malay male scholars as trivial as they believed that its recitation could arouse immoral emotions in listeners.8 According to the colophon, this syair was copied by an anak peranakan (local-born person of mixed origins). Collection of the Leiden University Library, Cod.Or 1965.

In the preface of Cetra Empat Orang Fakir (Tales of the Four Dervishes), the translator Mahmud bin Sayid Mu’alim bin Arsyad Marican recounts how he was introduced to this story by his Jawi Peranakan9 friend in Singapore. He also writes that his Malay work was translated from a Persian text attributed to the famous Sufi Amir Khusrau Dehlavi (1253–1325). Professor Vladimir Braginsky10 has, however, identified Mahmud’s source as a popular Urdu translation of Amir Khusrau’s work by Mir Amman (1750–1837) titled Bagh-o bahar (The Garden and Spring Season). First translated in the Islamic year 1262 (1846) and then transcribed in 1263 (1847), this manuscript by Mahmud is early evidence of the wave of literary contacts forged between Islamic India and the Malay world in the 19th century. The colophon – which mentions the names of the translator and copyist as well as the date and place it was completed (Singapore) – is found below the inverted triangle depicted here. Collection of the National Library, Singapore, Accession no.: B16283380I.

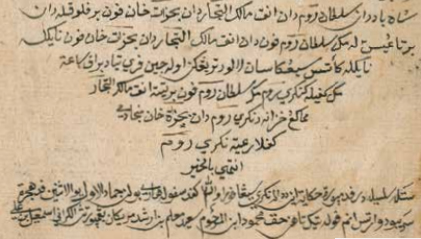

The Sulalat al-Salatin, or Genealogy of Kings, is one of the earliest and most famous texts in Malay literature. It is more popularly known as the Sejarah Melayu or Malay Annals, titles that were first coined by John Leyden, a Scotsman and friend of Stamford Raffles, in 1821.11 Composed around the 17th century, the Sulalat al-Salatin chronicles the history and genealogy of the Melaka Sultanate (1400 (?)–1511). The work was produced not so much to record history as to help bolster support for the Melakan rulers and their heirs in Johor and Riau. In the 19th century, a copy of the text was preserved as part of the regalia of the Riau court; it was wrapped in yellow silk and read out loud during certain court ceremonies. One of the episodes featured in the work recounts how Sang Nila Utama, a prince from Sumatra, arrived on the island of Temasek and established a city that he named Singapura. This particular copy of the manuscript – famously known as Raffles 18 – once belonged to Stamford Raffles, and is believed to be one of the earliest recensions of the original text. Collection of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland , United Kingdom, Raffles Malay 18.

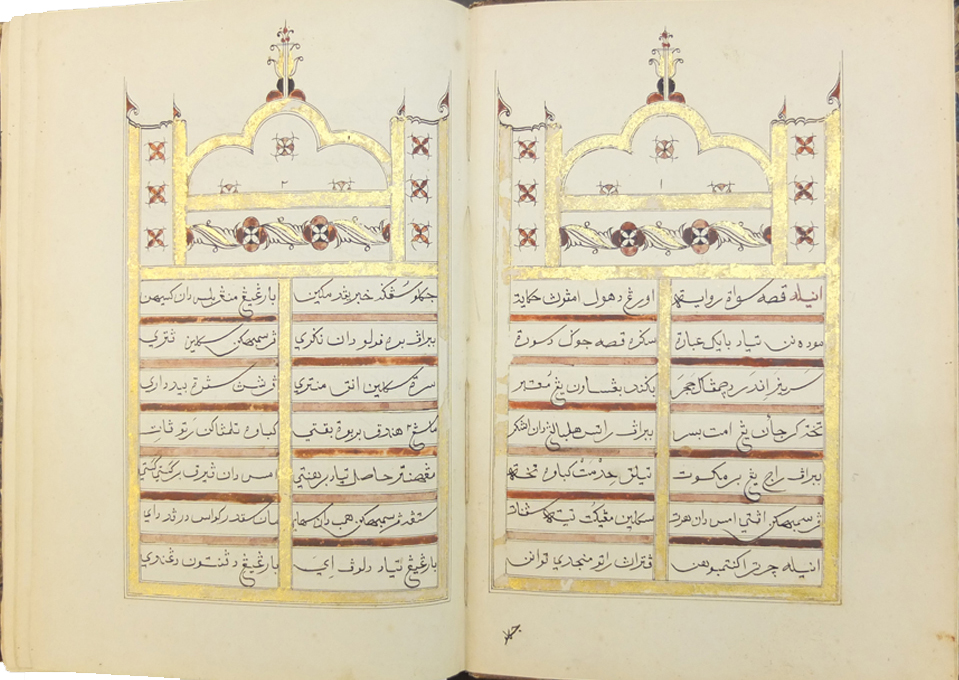

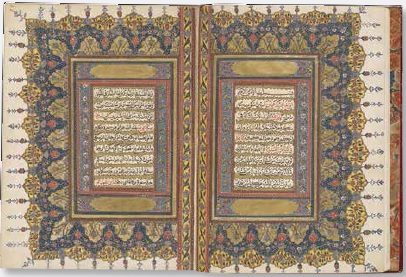

The majority of early Malay manuscripts are generally devoid of ornamentation. This rare and highly decorated manuscript from Penang, titled Taj al-Salatin (The Crown of Kings), is considered as one of the most beautiful by experts. The opening and closing pages are elaborately adorned with blue, red, yellow and gold design elements, while on other pages the text is enclosed within multicoloured frames. The decorative style of the opening pages seen here is reminiscent of Indo-Persian and Ottoman manuscripts.12 The manuscript is a didactic work describing the roles and responsibilities of kings and the nobility as well as commoners. It is believed to have been composed in Aceh in 1603 by Bukhari al-Johori or al-Jauhari (the “jewel merchant”) and was very popular among the ruling elite right up to the 19th century. The colophon states that the manuscript was copied by a scribe named Muhammad bin Umar Syaikh Farid on 4 Zulhijjah 1239 (30 July 1824). Collection of The British Library, Or. MS. 13295.

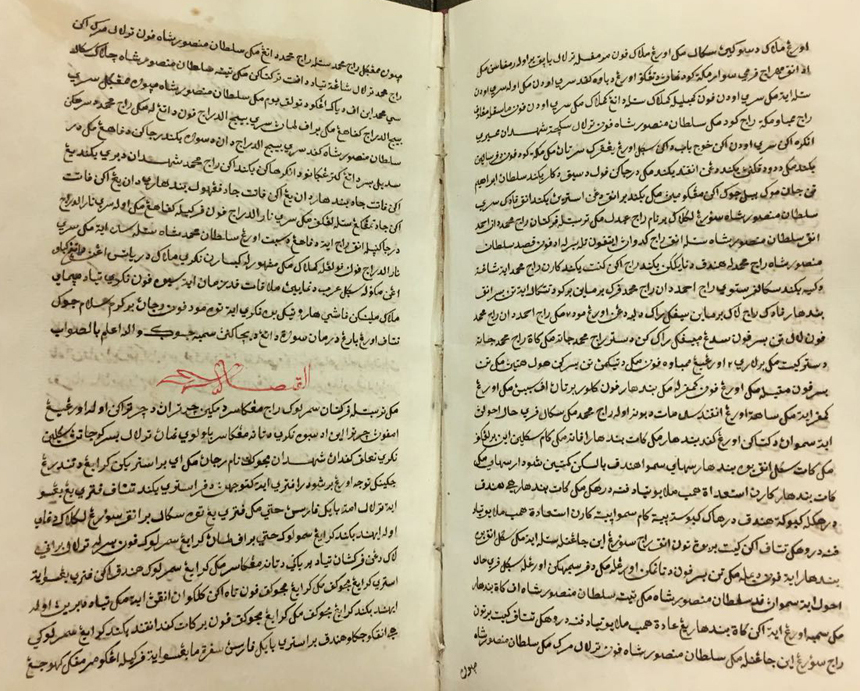

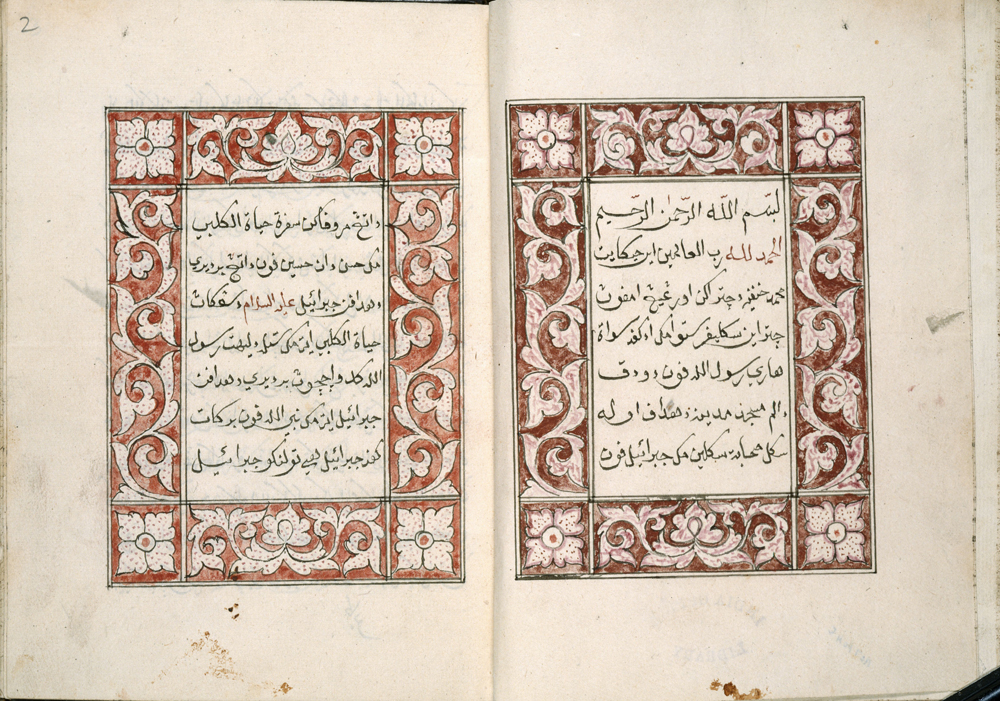

The Sejarah Melayu − an important literary work on the history and genealogy of the Malay kings of the Melaka Sultanate (1400–1511) tells of Melakan warriors who asked for the Hikayat Muhammad Hanafiah to be read to them as part of their preparations on the night before they went to war with the Portuguese invaders. The hikayat (narrative tale) recounts the exploits of the legendary Islamic warrior Muhammad Hanafiyyah who was the half-brother of Hasan and Hussein (the grandsons of the Prophet Muhammad).13 According to the scholar Brakel, the Hikayat Muhammad Hanafiah is believed to have been translated not long after the Persian original was written, possibly in northeast Sumatra in the 14th century.14 It continued to be very popular until the late 19th century and was reprinted many times by early Malay/Muslim printers in Singapore. According to the colophon, this manuscript was copied by Muhammad Kasim and completed on 29 Jamadilakhir 1220 (22 September 1805). Collection of The British Library Mss Malay B6, John Leyden collection.

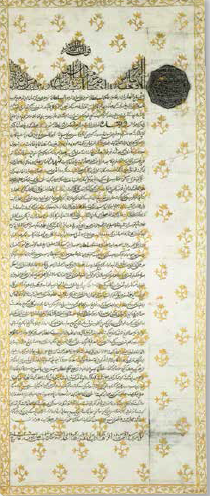

Stamford Raffles (1781–1826) was based in Melaka when he received this letter in February 1811 from Sultan Syarif Kasim (1766–1819), the ruler of Pontianak in western Kalimantan. Appointed as the Agent of the Governor-General to the Malay States, Raffles had sent letters to various indigenous rulers to ask for their support of the British invasion of Java. In the letter, Sultan Syarif requested for British support against “their” common enemy, the Sultan of Sambas (also in western Kalimantan).15 The letter ends with Sultan Syarif informing Raffles that he would be sending him two Malay manuscripts – a legal text (undang-undang) and the Hikayat Raja Iskandar. Raffles was a collector of Malay manuscripts and is believed to have single-handedly created – through his avid collecting activities – a public market for such written texts.16 Collection of The British Library, Mss Eur.D.742/1, f 33a.

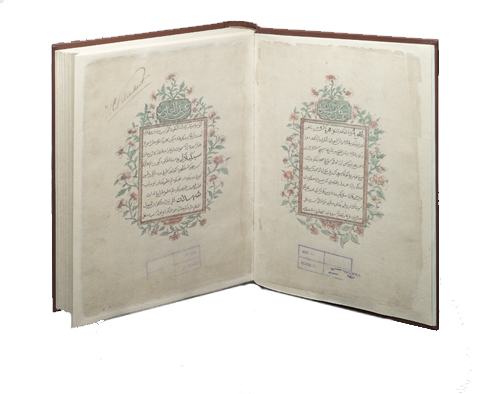

Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir (1797[?]–1854), better known as Munsyi Abdullah was a scholar and translator, and was famously known as the “father of Malay printing”. His autobiography, the Hikayat Abdullah (Stories of Abdullah), was published in 1849 in collaboration with Reverend Benjamin Keasberry (1811–1875), a Protestant missionary. Munsyi Abdullah was the first non-European to have his works published in Malay. Written as a memoir, the work is a record of the socio-political landscape of Singapore, Melaka and the kingdoms of Johor and Riau-Lingga at the beginning of the 20th century. It is one of the most impressive Malay works printed in the Straits Settlements during the 19th century. Shown here is the beautifully coloured double frontispiece of the Hikayat Abdullah. This copy was donated to the National Library, Singapore, by Revered George Frederick Hose in 1879. Collection of the National Library, Singapore, Accession no.: B03014389F.

Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir (1797[?]–1854), better known as Munsyi Abdullah was a scholar and translator, and was famously known as the “father of Malay printing”. His autobiography, the Hikayat Abdullah (Stories of Abdullah), was published in 1849 in collaboration with Reverend Benjamin Keasberry (1811–1875), a Protestant missionary. Munsyi Abdullah was the first non-European to have his works published in Malay. Written as a memoir, the work is a record of the socio-political landscape of Singapore, Melaka and the kingdoms of Johor and Riau-Lingga at the beginning of the 20th century. It is one of the most impressive Malay works printed in the Straits Settlements during the 19th century. Shown here is the beautifully coloured double frontispiece of the Hikayat Abdullah. This copy was donated to the National Library, Singapore, by Revered George Frederick Hose in 1879. Collection of the National Library, Singapore, Accession no.: B03014389F.

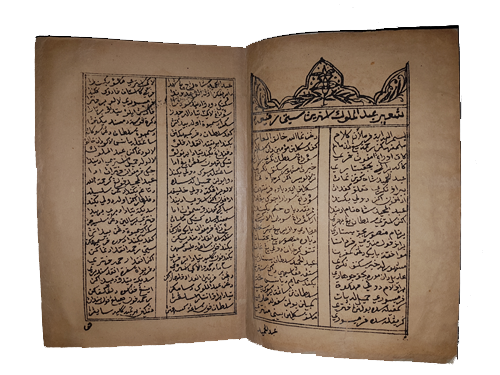

Like traditional handwritten manuscripts, printed syair and hikayat were recited aloud in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. A popular syair at the time was the Syair Abdul Muluk (Poem of Abdul Muluk) as evidenced by the number of multiple editions by various printers.17 This particular edition shown here was lithographed by one of the early prominent printers, Muhammad Amin, in the Islamic year 1311 (1893/4). The romantic poem is believed to have been composed by Raja Salihah18 of the Riau court in Penyengat. She is the younger sister of Raja Ali Haji, scholar and author of Tuhfat al-Nafis (The Precious Gift) which recounts the story of the relationship between the Malay and Bugis rulers. The protagonist in the poem is Abdul Muluk’s second wife, Siti Rafi’ah, who disguised herself as a man in order to rescue her husband and his first wife from captivity. Collection of the National Library, Singapore, Accession no.: B29362100A.

Tan Huism is Deputy Director of Content and Services at the National Library, Singapore, where she oversees exhibitions and the Singapore & Southeast Asia collections.

Tan Huism is Deputy Director of Content and Services at the National Library, Singapore, where she oversees exhibitions and the Singapore & Southeast Asia collections.

NOTES

-

Brown, C.C. (1976). Sejarah Melayu, or, Malay annals (p. 162). Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.503 SEJ) ↩

-

Shellabear, W.G. (1967). Sejarah Melayu (p. 264). Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: Malay RCLOS 959.5 SEJ) ↩

-

See Ding, C.M. (1987, October). Access to Malay manuscripts. Bidragen tot de Taal-, Land-en Volkenkunde, 143 (4), 425–451. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Proudfoot, I. (2002). From recital to sight reading: The silencing of texts in Malaysia. Indonesia and the Malay World, 30 (87), 117–144. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

The term “Muslim” is used here in the same way as Ian Proudfoot, to refer to the religious faith of the agents who produced the materials and not necessarily the content of the publications. See Proudfoot, I. (1993), Early Malay printed books: A provisional account of materials published in the Singapore-Malaysia area up to 1920, noting holdings in major public collections (pp. 27, 432). Malaysia: Academy of Malay Studies and the Library, University of Malaya. (Call no.: RSING 015.5957 PRO) ↩

-

Amin Sweeney was one of the first scholars to stress the importance of the oral in written Malay literature. See Sweeney, A. (1980). Authors and audiences in traditional Malay literature. Berkeley: Center for South and Southeast Asia Studies, University of California, Detroit, Mich. distribution by the Cellar Book Shop. (Call no.: RCLOS 899.23009 SWE) ↩

-

Panji tales from ancient Java recount the adventures of the hero named Panji who takes on different disguises and names in search of his beloved princess. ↩

-

Mulaika Hijjas. (2011). Victorious wives: The disguised heroine in 19th-century Malay syair. Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSEA 899.2810093522 HIJ) ↩

-

Jawi Peranakan refers to the children of Indian Muslim and Malay marriages. ↩

-

Braginsky, V. (2009). The story of four dervishes: The first translation from Urdu in traditional Malay literature. Jurnal e-Utama, 2. Retrieved from Jurnal e-Utama website. ↩

-

The first English translation of the Sejarah Melayu was by John Leyden (1775– 1811), which was published posthumously in 1821. See Leyden, J. (1821). Malay annals/translated from the Malay language, by the late Joh Leyden. With an introduction, by Sir Stamford Raffles.London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Annabel Gallop has done an in-depth study of the design of this manuscript and raised the possibility of a Penang style of manuscript decoration. See Gallop, A. (n.d.). Is there a Penang style of Malay manuscript illumination? Retrieved from Malay Concordance website. ↩

-

It is believed that early Malay literature inspired by Persian sources evolved over time to be less Shi’itic, although some traces still remain. ↩

-

Brakel, L.F. (1975). The Hikayat Muhammad Hanafiyyah: A medieval Muslim-Malay romance (pp. 54–57). The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff. (Call no,: RSEA 899.2300981 BRA) ↩

-

For the entire transcript and translation of this letter, see Ahmat Adam. (2009). Letters of sincerity: The Raffles collection of Malay letters (1780–1824): A descriptive account with notes and translation. Kuala Lumpur: Malaysia: The Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. (Call no.: RSEA 959.503 AHM) ↩

-

Proudfoot, 2002, pp. 117–144. ↩

-

There are debates as to who might be the author of the Syair Abdul Muluk. The poem has also been attributed to Raja Ali Haji. For the discussions, see Braginsky, V.I. (2004). The heritage of traditional Malay literature: A historical survey of genres, writings and literary views (p. 542). Leiden: KITLV Press. (Call no.: RSEA 899.28 BRA) ↩