Early Malay Printing in Singapore

Mazelan Anuar tracks the rise and decline of Malay printing and publishing in 19th-century Singapore, and profiles two of the most prolific printers of that period.

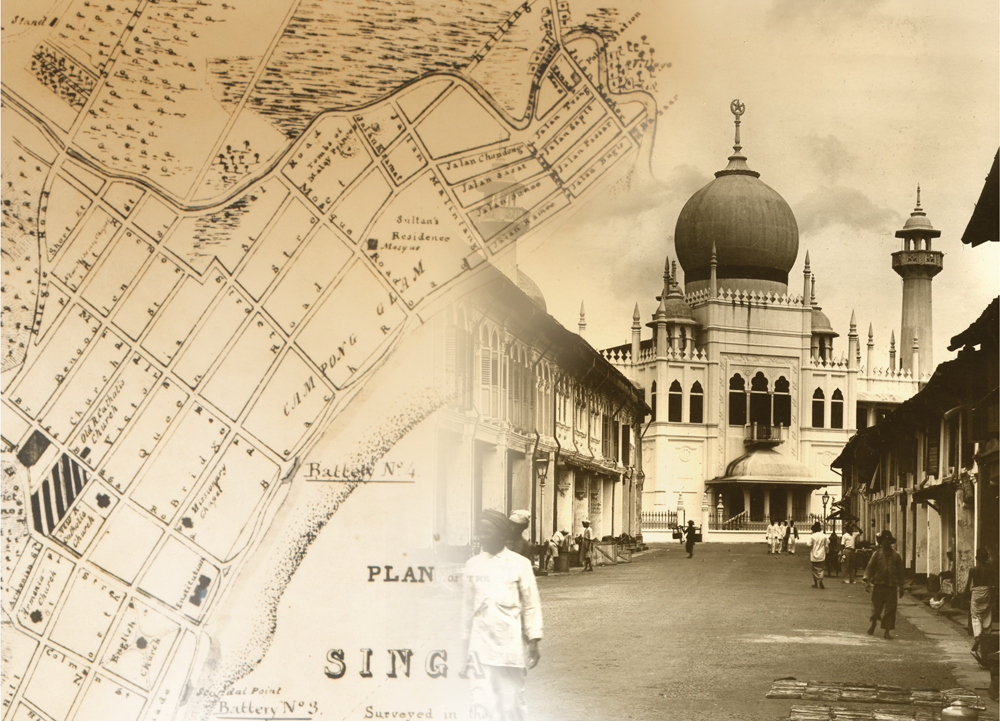

A composite image showing Kampong Glam from a cropped section of Plan of the Town of Singapore, 1843. Urban Redevelopment Authority, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore; and Sultan Mosque, c. 1928. Denis Santry Collection, National Library Board. Courtesy of Glen Christian.

A composite image showing Kampong Glam from a cropped section of Plan of the Town of Singapore, 1843. Urban Redevelopment Authority, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore; and Sultan Mosque, c. 1928. Denis Santry Collection, National Library Board. Courtesy of Glen Christian.Inscriptions in Old Malay can be traced back to the 7th century. These inscriptions from the pre-Islamic Malay world, such as the ones found on a small stone in Kedukan Bukit in Palembang, Indonesia, used vocabulary and scripts that are of Indian origin. The expansion of the Srivijaya kingdom from Sumatra to other parts of the Malay Archipelago resulted in the process of Indianisation that first shaped the cultural and religious practices of the Malays, including language and the art of writing.1 Additionally, words borrowed from Indian languages, especially Sanskrit, were introduced into the Malay vernacular and widely used in ritual, law and court documents.2

Old Malay remained in use as a written language right up to the end of the 14th century when the influence of Islam became more widespread in the region. By this time, Jawi – an Arabic writing script adapted for the Malay language – had been introduced as evidenced by Jawi inscriptions found on the Terengganu Stone3 and gravestones of a princess in Minye Tujuh (or Tujoh) in Aceh, Indonesia.4

The earliest compilations of Malay vocabulary by non-Malays were believed to have been undertaken by the Chinese in the 15th century, as well as the Italian scholar and explorer Antonio Pigafetta between 1519 and 1522, on his voyage around the world with the Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan. The listing of 482 Malay words and phrases by the Chinese was carried out after 1403 when diplomatic relations between China and Melaka were established.5 Pigafetta’s efforts at compiling more than 400 entries took place after the fall of Melaka to the Portuguese in 1511.6

The Proliferation of Malay Works

Publications in the Malay language were printed as early as the 17th century in Europe. Frederick de Houtman’s Dutch-Malay phrasebook, Spraeck ende woord-boeck, Inde Maleysche ende Madagaskarsche Talen, published in 1603, is the first of such works. Apart from vocabularies and phrasebooks, translations of the Bible and other Christian tracts into Malay were also undertaken. Due to the influence of colonialisation by Western powers, European-Malay imprints adopted romanised Malay script in these publications. By the 19th century, school textbooks as well as literary and general works in romanised Malay were published.7

Although the printing press8 was introduced in Southeast Asia in the late 16th century, the first Malay book was printed in Batavia (now Jakarta) in the Malay archipelago only in 1677; it was a Malay-Dutch dictionary, a new edition by Frederick Gueynier based on Caspar Wiltens’ Vocabularium, ofte Woortboeck, naer ordre van den Alphabet int’t Duytsch-Maleysch ende Maleysch- Duytsch (1623).

In 1758, the first complete Malay Bible in Jawi was published by Seminary Press, a printing house established in Batavia in 1746. Stricter controls imposed by the Dutch East India Company in the second half of the 18th century saw no other Malay books being printed after this period.9

In the early 19th century, the missionaries of the London Missionary Society – a non-denominational Protestant society founded in 1795 in England – set up stations in Melaka, Penang, Singapore and Batavia, with the ultimate aim of penetrating China and converting the Chinese to Christianity. Missionary activity in China was frowned upon by the authorities and Europeans were barred from living and travelling in the country; Canton (now Guangzhou) was the only port opened to European traders.

These locales in the Far East, which served as popular ports-of-call for the large numbers of Chinese junks sailing from Southern China, were seen as ideal interim bases for proselytising because of their huge Chinese populations. In Singapore alone, no fewer than 100 Chinese junks visited every year. The missionaries would take the opportunity to visit and proselytise to those on board, supplying them with religious texts and scriptures for distribution in China.

The missionaries also set up printing presses at these locales to publish Christian works in the languages of the local populace.10 Printing in Singapore began with the arrival of Danish missionary, Reverend Claudius Henry Thomsen, and Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir (better known as Munshi Abdullah), the learned Malay teacher and translator from Melaka. Both men had collaborated on a number of Malay-language works together. In 1823, along with another missionary, Samuel Milton, Thomsen established Mission Press, the first printing press in Singapore, after being granted approval by the colonial authorities.11

Thomsen returned to England in 1834, and the printing of Malay works was taken over by the Protestant missionary, Reverend Benjamin Keasberry, who arrived in Singapore in 1839. Keasberry also engaged the services of Munshi Abdullah who helped with the translation of works into Malay and the operation of the press. Munshi Abdullah’s original literary works, such as the famous Hikayat Abdullah (Stories of Abdullah), were also published by Keasberry. The latter continued to print in Malay until the 1860s when the first indigenous Malay/Muslim printers and publishers emerged in Singapore.12

Printers of Kampong Gelam

The Malay printing and publishing houses were established mainly by immigrants from Java. They settled in the Kampong Gelam (or Glam) area – in the vicinity of Sultan Mosque – a bustling commercial centre where the local Muslim community would gather on Fridays after their prayers at the mosque. It was also an area that served many Hajj pilgrims, especially those from Indonesia, on their stopover in Singapore on the way to Mecca.13

Two of the most prolific Malay printers in mid- to late- 19th-century Singapore were Haji Muhammad Said bin Haji Arsyad of Semarang and Haji Muhammad Siraj bin Haji Salih of Rembang. It was the practice at the time to mention the places of origin – both Semarang and Rembang were towns in Java, Indonesia – after their names. Haji Muhammad Said and his sons published more than 200 Malay-language publications between 1873 and 1918. In the same period, Haji Muhammad Siraj published around 80 books.14

Haji Muhammad Said, along with fellow Javanese Haji Muhammad Nuh bin Haji Ismail ahl al-Badawi of Juwana, Syaikh Haji Muhammad Ali bin Haji Mustafa of Purbalingga, Haji Muhammad Salih of Rembang (Haji Muhammad Siraj’s father), Haji Muhammad Tahir and Encik Muhammad Sidin, were the pre-eminent Malay printers in Singapore between 1860 and 1880. Early lithographic publications of this period tend to be jointly produced with contributions from copyists and owners of the text and press, with the printers and sellers duly acknowledged in the colophon (a statement providing information on the authorship and printing of the book, often accompanied by an emblem). The printers tended to produce books that resembled the form of the Malay manuscript.15

The Malay printing industry in Singapore continued to flourish in the following two decades, with printing activity peaking in the 1880s. Haji Muhammad Said retained his position as the leading printer alongside other second-generation printers, such as Haji Muhammad Siraj and his brother, Haji Muhammad Sidik; Haji Muhammad Amin bin Abdullah; and Haji Muhammad Taib bin Zain, who later became more prominent in the industry.16

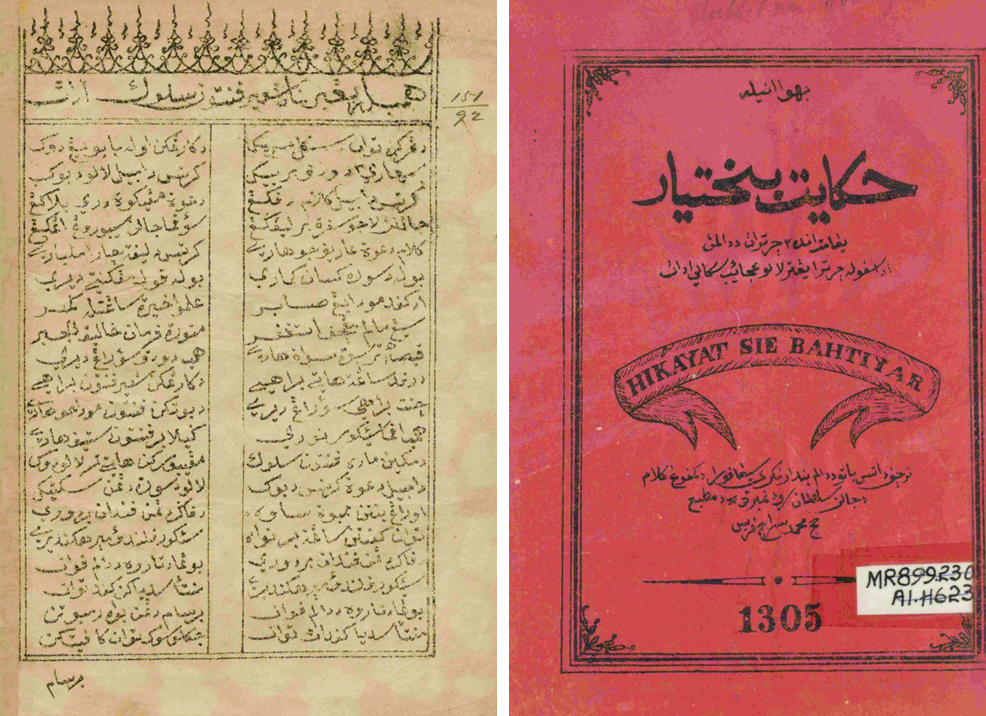

(Left) Hambalah Yang Bernama Shaer Pantun Seloka Adanya was printed by Haji Muhammad Said in 1900. This book of poems mentions that his shop was located in front of Sultan Mosque. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Accession no. B18153100H)

(Left) Hambalah Yang Bernama Shaer Pantun Seloka Adanya was printed by Haji Muhammad Said in 1900. This book of poems mentions that his shop was located in front of Sultan Mosque. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Accession no. B18153100H)(Right) Printed by Haji Muhammad Siraj in 1888, Hikayat Bakhtiar is a collection of 10 popular stories found in both manuscripts and printed books. This book is the second edition of the hikayat. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Accession no. B03013464J)

Haji Muhammad Said bin Haji Arsyad

Much of Haji Muhammad Said’s printing and publishing activities were researched and documented by the late Dr Ian Proudfoot, one of the greatest scholars on early Malay printing. Proudfoot studied information found in the Straits Settlements Government Gazette, publications produced by Haji Muhammad Said and his sons as well as other contemporaneous literature.

Haji Muhammad Said’s business went by several names, such as Matbaah/Matba’ Haji Muhammad Said, Matbaah al-Saidi, Haji Muhammad Said Press and Saidiah Press. Haji Muhammad Said operated out of a few locations in the vicinity of Kampong Gelam. His early publications produced before the 20th century indicate that his business was located at 47, 48 and 51 Jalan Sultan. Sometime in 1907, his shop and press moved to 82 Arab Street which was also known as Kampung Silung.17

Haji Muhammad Said had four sons: Haji Muhammad Majtahid, Haji Abdullah, Khalid and Haji Hamzah, all of whom followed in their father’s footsteps in the book printing business. In 1892, the family established a branch office in Penang. By 1898, Haji Muhammad Majtahid was entrusted to run the branch office. He also set up a bookshop in Penang.18

In the beginning of the 20th century, the family business shifted its focus from printing to retailing books. Haji Abdullah, another son, assumed the main responsibility of running the bookshop in Singapore and marketing its publications. For instance, in 1912, the family publicised that their bookshop carried Malay books printed in Mecca, Istanbul, Russia, Egypt and Bombay. By 1917, the business was operating from 124 Arab Street.19

Haji Muhammad Siraj bin Haji Salih

It is not known when Haji Muhammad Siraj arrived in Singapore. His father, Haji Salih and his brother, Yahya, were also printers. He may have printed books in Singapore as early as 1868. Proudfoot identified publications by Siraj up to 1918, but some of these could have been produced by his successors.20

Haji Muhammad Siraj initially operated out of 44 Jalan Sultan but moved to No. 43 in 1887. Although he was a prolific printer, he was better known for his entrepreneurial endeavours. By 1891, Haji Muhammad Siraj had become the largest Muslim bookseller in Singapore and employed 10 staff in his publishing house. He sold a variety of publications at his bookshop, ranging from government school textbooks to newspapers from Cairo as well as syair (poems) and hikayat (stories) produced by his own printing press and other Kampong Gelam publishers.21

Haji Muhammad Siraj advertised and frequently produced catalogues of his stocks. This helped to attract customers and build his business, prompting orders to come through by mail and the network of agents he had established in Melaka, Penang, Perak, Batavia and Sarawak.22

Haji Muhammad Siraj was also a competent copyist-editor. He specialised in syair, hikayat and kitab (religious texts). Among the works he was credited as copyist include Yatim Mustafa (1887), Terasul (1894), Abdul Muluk (1901) and Indera Sebaha (1901). These were not all produced by his own printing press. Apart from Malay and Arabic texts, Haji Muhammad Siraj was also the copyist for several kitab written in Javanese pegon script, a system of writing that uses the Arabic alphabet.23

Between 1889 and 1891, Haji Muhammad Siraj was editor of Jawi Peranakkan (1876–95), the first Malay language newspaper in Singapore. He advertised his bookshop and the various titles it carried in the weekly paper during this period.24

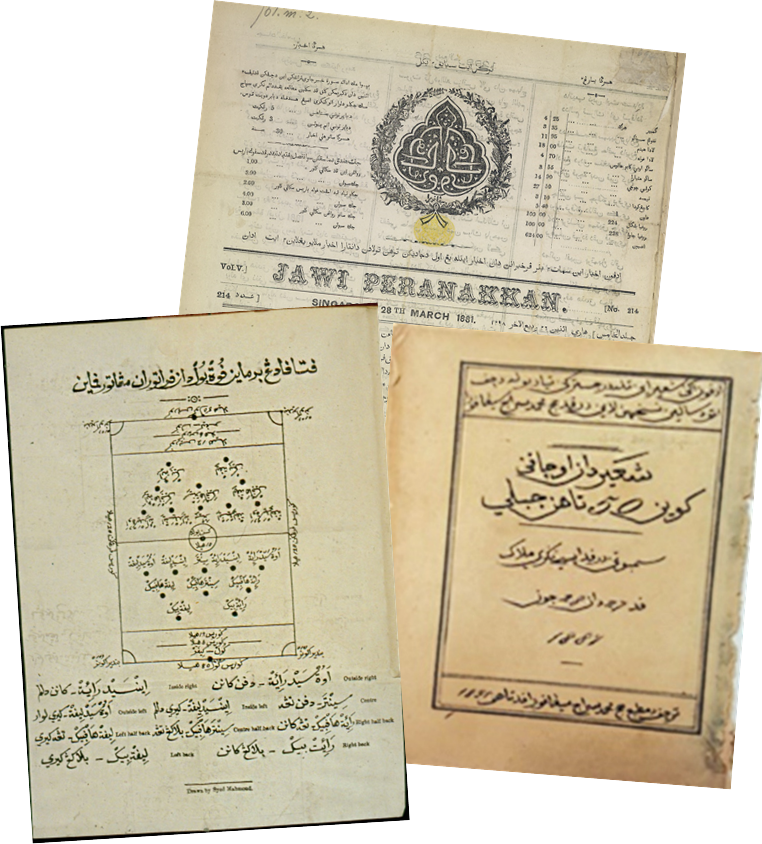

(Clockwise from top)

(Clockwise from top)Haji Muhammad Siraj bin Haji Salih was the editor of Jawi Peranakkan, the first Malay-language newspaper in Singapore, from 1889 to 1891. The newspaper was set up in 1876 by a group of prominent Jawi Peranakan, the Straits-born children of Malay-Indian parentage. The weekly newspaper was published every Monday in Jawi. It carried official government notices, letters from readers, editorials and syair (poems), and was in circulation until 1895. Pictured here is the 28 March 1881 (vol. 5, no. 214) edition. Collection of The British Library, OP434.

One al-haqir Munshi Muhammad Ja’afar bin Abdul Karim witnessed the festivities held in Melaka to celebrate the golden jubilee of Queen Victoria’s accession, and requested Haji Muhammad Siraj to print this commemorative book titled Sha’ir dan Ucapan Queen 50 Tahun Jubilee Sambutan Daripada Isi Negeri Melaka Pada 27 dan 28 June 1887. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Accession no. B29362101B).

In 1895, Haji Muhamad Siraj bin Haji Salih engaged the American Mission Press to print Peraturan Bola Sepak, a guidebook of football rules, for the Darul Adab Club. Pictured here is a fold-out plan of a football field showing the position of the players. Collection of The British Library, 14628.b.2.

Haji Muhammad Siraj was an astute and resourceful businessman. He accepted printing commissions from Melaka and carried out letterpress printing for his clients, a method that allows selected parts of the page to be printed instead of printing the entire page. In 1895, he engaged the services of the American Mission Press – which owned a letterpress printer – to print Peraturan Bola Sepak, a guidebook of football rules, for the Darul Adab Club, a social and recreational body. The guidebook combined letterpress text and lithographed diagrams.25

Haji Muhammad Siraj held various positions in the club, including the role of vice-president, honorary secretary and assistant secretary. At a special meeting of the club held on 4 February 1901, he read out the special prayer that he had penned to observe the passing of Queen Victoria in January 1901. The prayer was published in The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser on 5 February 1901.26 In 1907, he composed a poem to commemorate the visit of the Sumatran king, Sultan El Syed Al Sharif Hashim Abdul Jalil Saif Al Din of Siak, Sri Indra Pura, to the Darul Adab clubhouse. The sultan was an honorary member of the club and the visit on 30 August was his first.27

In his various correspondences in English, Haji Muhammad Siraj signed off as H.M. Sirat, for reasons known only to himself.28 Nevertheless, this has enabled us to locate information on him in English newspapers such as The Singapore Free Press and The Straits Times.

Haji Muhammad Siraj passed away on 28 October 1909, and was laid to rest at the River Valley Road Mohammedan Cemetery. The Straits Times reported the news on 29 October, and declared that he was “one of the best known of the Malays in Singapore, who carried on the business of a book-seller and stationer in Sultan Rd and was well-known as a leader in Malay clubdom”. It was estimated that over 4,000 people turned up for the funeral procession.29

The Decline of Malay Printing

After 1900, there was a decline in Malay lithographic printing output. Between 1890 and 1899, a total of 99 titles were registered with the colonial authorities. In the next decade, from 1900 to 1909, the number fell to 50 titles, and this dropped further to only 12 between 1910 and 1919. Lithographic printing was eventually overtaken by letterpress printing, which proved to be a more efficient method that produced better quality printing.

Furthermore, the Malay book market was flooded with publications imported from India and the Middle East by Malay booksellers. The competition affected the business of many local publishers who were forced to scale back and decrease their print output. Eventually, many ceased operations. At the same time, newspapers such as Utusan Malayu and Lembaga Melayu became more popular with the rising number of urban Malays; the new medium was better able to fulfil the information needs of the community as well as adapt to their changing reading patterns.30

After the 1920s, Malay lithographic book production became a lost art. However, the role that early Malay printers played in ushering a new era from the manuscript tradition should not be forgotten. Their important legacy has been preserved in the works they produced from the mid- to late-19th century, during the nascent period of Malay printing and publishing in Singapore.

FROM MANUSCRIPT TO PRINT

Before the adoption of Islam as a religion by Malay rulers in the 13th century, literacy was the reserve of the royal, noble and priestly classes. A core injunction for Muslims to read the Qur’an subsequently encouraged literacy among the masses and stimulated a new avenue of output for scribes, who painstakingly copied religious texts (kitab) so that more people could have access to them.

Scribes and copyists continued to play an important role until the 19th century where lithography printing – which reproduced the physical characteristics of a handwritten manuscript cheaply and in large quantities – still required the ability to write in Jawi. Further improvements to printing technology from the 20th century onwards, however, rendered scribes and copyists obsolete as their role was taken over by technicians who were proficient in operating printing presses.

Tales of the Malay World: Manuscripts and Early Books

Be sure to catch this exhibition of old Malay manuscripts and printed books from the 18th to early 20th centuries at level 10 of the National Library Building. The exhibition ends on 25 February 2018. For more information, go to https://exhibitions.nlb.gov.sg/.

Mazelan Anuar is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. His research interests are in early Singapore Malay publications and digital librarianship. He manages the National Library’s Malay language collection as well as the NewspaperSG portal.

Mazelan Anuar is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. His research interests are in early Singapore Malay publications and digital librarianship. He manages the National Library’s Malay language collection as well as the NewspaperSG portal.

NOTES

-

Juffri Supa’at & Gopaul, N. (Eds.). (2009). Aksara: Menjejaki tulisan Melayu = Aksara: The passage of Malay scripts (p. 37). Singapore: National Library Board. (Call no.: Malay RSING 499.2811 AKS) ↩

-

Winstedt, R. (1944, October. Indian influence in the Malay world. The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, 2, 186–195, pp. 186–187. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

The Terengganu Stone constitutes the earliest evidence of Jawi writing (Malay writing based on Arabic alphabet) in the Malay Muslim world of Southeast Asia. ↩

-

Teeuw, A. (1959). The history of the Malay language: A preliminary survey. Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, Deel, 115 (2), 138–156, pp. 140, 149. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Edwards, E.D., & Blagden, C.O.A. (1931). A Chinese vocabulary of Malacca Malay words and phrases collected between A. D. 1403 and 1511 (?). Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London, 6 (3), 715–749, pp. 718–748. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Bausani, A. (1960, December). The first Italian-Malay vocabulary by Antonio Pigafetta. East and West, 11 (4), 229–248, pp. 233–240. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Gallop, A.T. (1990). Early Malay printing: An introduction to the British Library collections. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 63 (1) (258), 85–124, p. 85. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

A printing press is a device that applies pressure to an inked surface resting upon a print medium, usually paper or cloth, to transfer the ink. ↩

-

Gallop, 1990, pp. 87, 92. ↩

-

Gallop, 1990, pp. 92–93. ↩

-

National Library Board. (2008). Mission Press written by Lim, Irene. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. ↩

-

Gallop, 1990, pp. 98, 105. ↩

-

Proudfoot, I. (1993). Early Malay printed books: A provisional account of materials published in the Singapore-Malaysia area up to 1920, noting holdings in major public collections (pp. 31–32). Kuala Lumpur: Academy of Malay Studies and the Library, University of Malaya. (Call no.: RSING 015.5957 PRO-[LIB]) ↩

-

Warnk, H. (2010). The collection of 19th century printed Malay books of Emil Lüring. Sari – International Journal of the Malay World and Civilisation, 28 (1), 99–128, p. 104. Retrieved from UKM Journal Article Repository website. ↩

-

Warnk, 2010, p. 104. ↩

-

The late queen. (1901, February 5). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Darul Adab Club. (1907, September 2). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Proudfoot, I. (1987, Disember). A nineteenth-century Malay bookseller’s catalogue. Kekal abadi: Berita Perpustakaan Universiti Malaya, 6 (4), 1–11, p. 11. Kuala Lumpur: Perpustakaan Universiti Malaya. (Call no.: Malay RSEA 027.7595 UMPKA) ↩

-

Social and personal. (1909, October 29). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Warnk, 2010, p. 105. ↩