Scots in Singapore: Remembering Their Legacy

The Scots in colonial Singapore lent their names to many of the city’s famous landmarks. Graham Berry pays tribute to the contributions of his fellow men.

A photo of a European man wearing a sarong in a print resembling a Scottish tartan pattern, c.1900. All rights reserved, Falconer, J. (1987). A Vision of the Past: A History of Early Photography in Singapore and Malaya: The Photographs of G. R. Lambert & Co., 1880–1910 (p. 154). Singapore: Times Editions. (Call no.: RSING 959.570049163 BER).

A photo of a European man wearing a sarong in a print resembling a Scottish tartan pattern, c.1900. All rights reserved, Falconer, J. (1987). A Vision of the Past: A History of Early Photography in Singapore and Malaya: The Photographs of G. R. Lambert & Co., 1880–1910 (p. 154). Singapore: Times Editions. (Call no.: RSING 959.570049163 BER).Singapore’s roots as a trading hub were planted along the banks of the Singapore River in 1819 when Stamford Raffles, together with William Farquhar, established a port for the British East India Company (EIC). Shortly after, civic institutions were set up by colonial administrators and merchants founded trading houses near the river, along with plantations further inland where they built palatial mansions with sprawling gardens.

Initially, trading in Singapore was dominated by the EIC, which held a monopoly jealously guarded by its own powerful armed forces, engineers and aggressive administration. Following in the wake of the EIC were independent traders, privateers and explorers, eager to reap the riches from the settlement’s vantage position as a trading hub and transform the island into a prized colony of the British Empire.

As the settlement developed from 1819 onwards, districts, features, thoroughfares and bridges all demanded to be named. In modern Singapore, many of these places and landmarks still bear the names given by EIC officials and their successors. As large numbers of EIC merchants, military personnel and administrative staff were Scots, it is no surprise that Scottish names dominate Singapore’s iconic town centre, the river environs as well as several prime residential areas.

James MacRitchie, John Turnbull Thomson, John Crawfurd, John Anderson, Robert Fullerton, Thomas Murray Robertson and William George Scott. These names – which read like the who’s who of the early Scottish community in Singapore − have left an indelible mark on the island. Who were these men and what were their contributions to Singapore? These are themes that I explore in my book, From Kilts to Sarongs: Scottish Pioneers of Singapore. This essay considers a small selection of the city’s more prominent landmarks and place names that reflect the heritage of its Scottish pioneers.

Residents of Singapore: Farquhar and Crawfurd

It is a travesty that Singapore bears no mark of William Farquhar – the man who arguably did more than any other colonial officer to establish the nascent trading settlement in 1819 and manage its early progress in the face of doubts from home and dangers from hostile territories. Born on February 1774 in Fetteresso, near Aberdeen, Scotland, Farquhar was appointed as Resident and Commandant of Singapore soon after its founding.

Much has been written in history books about Raffles and not enough about Farquhar and his role in the early success of Singapore. Farquhar was present from the outset of the development of colonial Singapore. He was involved in the deliberations that resulted in Singapore being chosen as the new settlement of the EIC and at the negotiation of key treaties. Most importantly, in the absence of Raffles (who was stationed in Bencoolen), Farquhar ably administered what became a successful port and settlement. Unfortunately, Raffles and Farquhar fell out in grand fashion and the latter was summarily dismissed by Raffles on 1 May 1823.

Farquhar lived in the Kampong Glam area and the road where he lived was named Farquhar Street. The inexorable march of progress in modern Singapore, however, has obliterated this thoroughfare and no memorial remains of Farquhar today.

Farquhar’s successor as Resident in 1823 was also a Scot. Dr John Crawfurd was a physician born in 1783 on Islay, an island off the west coast of Scotland famed for its whisky distilleries. He joined the EIC as a surgeon and like Farquhar, quickly rose to a position of prominence. He knew Raffles and Farquhar as well as Lord Minto, another Scot, who was then Governor-General of India. Together these men embarked on the invasion of Dutch-controlled Java in 1811.

By all accounts, Crawfurd was a typical dour Scot with a reputation for parsimony. But he was an able diplomat and a highly professional administrator who not only built on the solid foundation laid down by Farquhar but had, by 1824, negotiated the Anglo-Dutch Treaty. This agreement ceded Singapore to the British, thereby removing any doubts about the future security of the settlement and its longevity.

Crawfurd is remembered in Singapore in the naming of Crawford Street, Crawford Lane and Crawford Bridge – albeit spelt with an “o” instead of the original “u” – that spans the Kallang River. The bridge was named so sometime at the turn of the 20th century when it was a timber structure supported by cast iron beams. In the 1920s, the bridge was replaced with a reinforced concrete structure embellished with a series of bow-string arches, and, in the early 1990s, it was expanded to accommodate a higher volume of traffic.

Horsburgh and Thomson

Many significant landmarks in Singapore bear the name of Scotsmen. One, which few people would have had a chance to visit, is the Horsburgh Lighthouse on the rocky ledge of Pedra Branca guarding the eastern approaches of the Singapore Strait. For many years, the sovereignty of this speck of land was a cause of territorial dispute until the International Court of Justice ruled in Singapore’s favour in 2008.

An 1851 painting of Horsburgh Lighthouse on Pedra Branca by John Turnbull Thomson, Government Surveyor for the Straits Settlements. The lighthouse, which was designed and built by Thomson in 1851, was named after James Horsburgh, a hydrographer with the East India Company. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

An 1851 painting of Horsburgh Lighthouse on Pedra Branca by John Turnbull Thomson, Government Surveyor for the Straits Settlements. The lighthouse, which was designed and built by Thomson in 1851, was named after James Horsburgh, a hydrographer with the East India Company. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.The 34-metre-high lighthouse, named after James Horsburgh, was completed in 1851. Horsburgh was born in Fife, Scotland, in 1762. At the age of 16, he became a seaman and through a combination of skill and hard work, rose through the ranks to become a talented hydrographer with the EIC. He charted sea routes between India and China, thus easing the way for ships to voyage to the east. Merchants in Hong Kong and Singapore recognised Horsburgh’s contribution in making the long and hazardous journey to the east less dangerous, and commissioned the lighthouse to be built in his memory.

The lighthouse, which bears a commemorative tablet dedicated to Horsburgh, was designed and built by another Scotsman, John Turnbull Thomson, who himself left a significant legacy to the built heritage of Singapore. Thomson was born in 1821 in the north of England to Scottish parents who had travelled south to find work. He was educated in Scotland and was appointed Government Surveyor for the Straits Settlements in 1841. For the next 12 years, Thomson served as both surveyor and engineer in Singapore. The many landmarks for which he was responsible include Dalhousie Obelisk, the tower and spire of the original St Andrew’s Church (later replaced by St Andrew’s Cathedral) and Thomson’s Bridge, which replaced Presentment Bridge – the first bridge built across the Singapore River in 1822. Thomson’s Bridge in turn was replaced by Elgin Bridge in 1862.

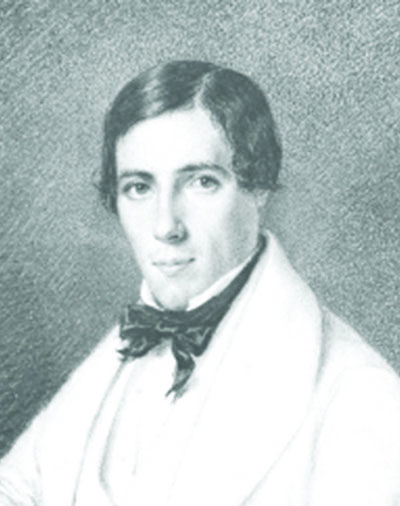

Portrait of John Turnbull Thomson, at 25 years of age, by Beyerhaus in 1845. Thomson was appointed Government Surveyor for the Straits Settlements in 1841, and served as both surveyor and engineer to Singapore for the next 12 years. All rights reserved, Hall-Jones, J., & Hooi, C. (1979). An Early Surveyor in Singapore: John Turnbull Thomson in Singapore, 1841–1853 (p. 35). Singapore: National Museum. (Call no.: RSING 526.90924 THO).

Portrait of John Turnbull Thomson, at 25 years of age, by Beyerhaus in 1845. Thomson was appointed Government Surveyor for the Straits Settlements in 1841, and served as both surveyor and engineer to Singapore for the next 12 years. All rights reserved, Hall-Jones, J., & Hooi, C. (1979). An Early Surveyor in Singapore: John Turnbull Thomson in Singapore, 1841–1853 (p. 35). Singapore: National Museum. (Call no.: RSING 526.90924 THO).Thomson Road is also named after him, and it is believed that he was the “ang mo” in Ang Mo Kio, having also constructed a bridge in that area. Ang Mo Kio in Hokkien literally translates into “Red-haired Man’s Bridge” – in reference to the bridge that once spanned Kallang River, close to what is today the junction of Upper Thomson Road and Ang Mo Kio Avenue 1.

Recreational Spaces

Despite its high population density, Singapore’s vision of becoming a City in a Garden is now a reality thanks to a combination of enlightened planning and the efforts of the National Parks Board. The benefits of having public spaces was recognised early in the colonial period; and two Scotsmen – James MacRitchie and Lawrence Niven – in particular, were instrumental in laying the foundations for the planners who came after them.

James MacRitchie was an engineer born in Southampton, England, to Scottish parents. He was sent to school in Scotland and then studied at Edinburgh University before training as an engineer in Glasgow. MacRitchie’s career took him to China, Japan and Brazil before he was appointed Municipal Engineer in Singapore in 1883, a post he held until his death in 1895. During those 12 years, MacRitchie was responsible for developing much of the infrastructure of the colony. His name, however, is associated principally with the much-loved MacRitchie Reservoir, which is now surrounded by nature reserves and enjoyed by both wildlife and recreational enthusiasts. MacRitchie was responsible for the enlargement of the reservoir as well as the development of its pumping and purification systems.

The name Lawrence Niven is less known in Singapore, but he stands as MacRitchie’s equal in creating another much loved recreational space. In 1860, Niven, who worked as a manager of a nutmeg plantation belonging to Charles Robert Prinsep, in the area of the present Prinsep Street, was recruited to develop a 23-hectare site in Tanglin into a garden. Niven dedicated himself to this task over the next 15 years while managing the Prinsep plantation at the same time. The eventual result was the Singapore Botanic Gardens, which was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in July 2015.

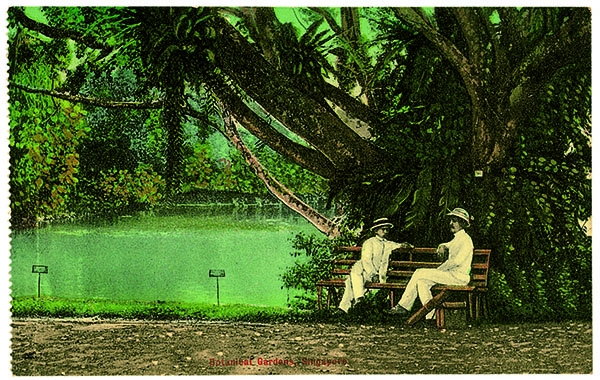

Two European gentlemen sitting by the lake at the Botanic Gardens in Singapore, c.1900. Courtesy of Cheah Jin Seng.

Two European gentlemen sitting by the lake at the Botanic Gardens in Singapore, c.1900. Courtesy of Cheah Jin Seng.Niven’s design laid the foundation of the gardens and he created many of its distinctive features, many of which are still apparent to this day. According to a 2014 article by Nigel P. Taylor,1 the Director of the Singapore Botanic Gardens, Niven “was almost certainly responsible for the classic English-style landscape design that the garden celebrates today”. Niven Road, close to the Prinsep plantation where he started his career in Singapore, is named after him.

There is another Scot whom we have to thank for preserving recreational space in Singapore – the first Resident, William Farquhar. The area ceded to the EIC to establish the settlement was limited, and much of the swampy land was unusable. Raffles had planned to reserve land north of the Singapore River for government buildings and use the adjoining parcel of land for European merchants. The merchants, however, pointed out to Farquhar that it would be more convenient if they could build their godowns next to the river to facilitate the loading and unloading of goods. Seeing the wisdom of this advice, Farquhar reserved the strip of land that eventually became known as the Esplanade. The Esplanade and Padang could have been built-up areas today had it not been for Farquhar’s far-sighted intervention.

Hotel, Quay and Bridges

At least one landmark hotel and prominent bridges and quays along the Singapore River bear the name of Scotsmen. The aforementioned Dalhousie Obelisk commemorates the visit of fellow Scot and then Governor-General of India, James Andrew Broun- Ramsay, the 10th Earl of Dalhousie, to Singapore in 1850. The Earl was born in Dalhousie Castle, the seat of the Earls of Dalhousie, located south of the capital city of Edinburgh.

The luxury Fullerton Hotel derives its name from Sir Robert Fullerton, born in Edinburgh in 1773. Fullerton was the first Governor of the Straits Settlements in 1826 when Penang, Singapore and Melaka were grouped together for ease of administration. The hotel occupies the former Fullerton Building (declared opened in 1928), which in turn took over the site of Fort Fullerton, built sometime in the first decade of the colony’s founding to guard the mouth of the Singapore River. Fullerton Road and Fullerton Square are also named after the same Scotsman.

Robertson Quay is named after the highly regarded Dr Thomas Murray Robertson. He trained as a physician in Edinburgh before practising at The Dispensary medical clinic at Commercial Square (now Raffles Place) with Dr Lim Boon Keng, a prominent Straits Chinese. The clinic was founded in 1879 by Robertson’s father, Dr J.H. Robertson.

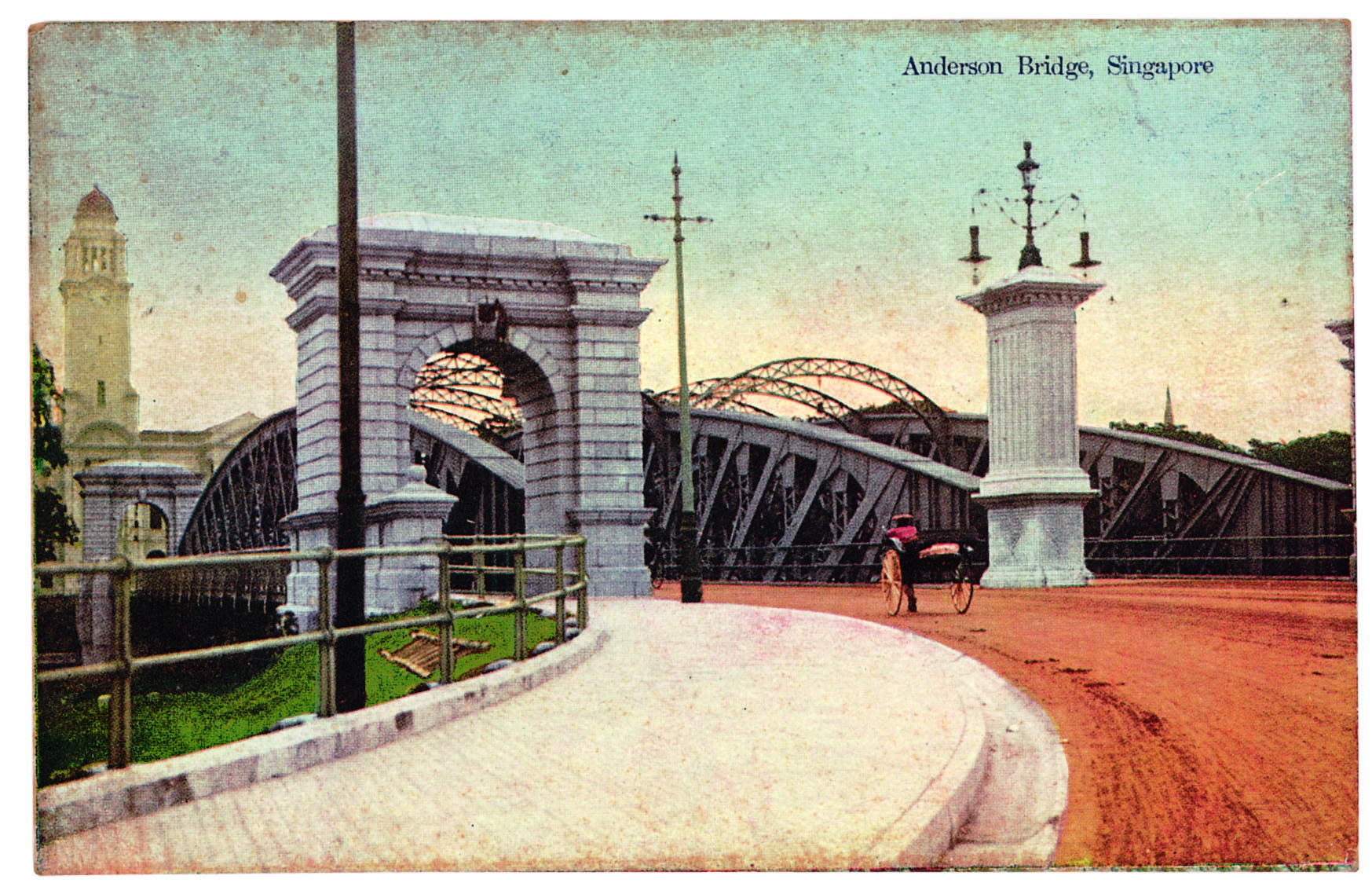

Sir John Anderson, born in Aberdeen in 1858, was Governor of the Straits Settlements from 1904 to 1911. Anderson Bridge across the Singapore River and Anderson Road are named after him. James Bruce, the 8th Earl of Elgin, was appointed Viceroy of India in 1862. He lent his name to the Elgin Bridge mentioned earlier. This bridge, which replaced Thomson’s Bridge in 1862, was dismantled in 1927 to make way for the present Elgin Bridge that opened two years later. Elgin Bridge straddles the Singapore River, and joins North Bridge Road to South Bridge Road.

View of Anderson Bridge with the clock tower of Victoria Memorial Hall in the background, undated. The bridge is named after John Anderson, Governor of the Straits Settlements from 1904 to 1911. Courtesy of Cheah Jin Seng.

View of Anderson Bridge with the clock tower of Victoria Memorial Hall in the background, undated. The bridge is named after John Anderson, Governor of the Straits Settlements from 1904 to 1911. Courtesy of Cheah Jin Seng.Residential Areas

The name Scott appears frequently in Singapore. One of the most sought-after pieces of real estate in modern Singapore is the site at the junction of Orchard Road and Scotts Road, stretching to that one-time haunt and watering hole of well-heeled colonials – the Tanglin Club. This was the estate of Captain William George Scott, a wealthy Scottish landowner who claimed to be a first cousin of the famous novelist and poet Sir Walter Scott. The picturesque and expansive gardens of Scott’s estate, a popular place for residents to gather and enjoy the cool of the evening and socialise, is a far cry from the Scotts Road of today with its upmarket malls and jostling shoppers.

Scott, who became the Harbour Master Attendant and Post Master in Singapore in 1836, gives his name to Scotts Road, while Claymore Road takes its name from the name of his house and estate. Claymore is an anglicisation of the Gaelic claidheamhmór, which means “broad sword”.

The densely urbanised district of MacPherson, with its busy main thoroughfare and MRT station, could not be further from the misty mountains of the Island of Skye, off the northwest coast of Scotland. Yet it was here in 1817 that the man whose name still resonates in Singapore, Ronald MacPherson, was born. Like many young men from Skye, MacPherson’s options were limited and so he entered into military service with the Madras Artillery regiment of the EIC in 1836 when he was 19. In 1842, MacPherson was posted to Penang where he spent six years before being transferred in 1855 to Singapore as the Executive Engineer and Superintendent of Convicts.

As the city engineer, MacPherson was responsible, like John Turnbull Thomson before him, for developing infrastructure and constructing functional civic buildings. Accomplishing this brief with flair, MacPherson’s legacy includes St Andrew’s Cathedral (1861) – incidentally named after the patron saint of Scotland. MacPherson designed the cathedral, which was built by Indian convict labour, in a Neo-Gothic architectural style inspired by Netley Abbey in Hampshire, England. In the cathedral grounds is a monument with a Maltese cross erected in his memory.

Scottish Ironwork

The bulk of the iron and steel produced for the British Empire was forged in Scottish foundries. Singapore, which had little or no domestic production, imported most of the ironwork it needed from Scotland. Glasgow-based companies like MacFarlane and Company and P & W MacLellan provided construction materials that enhance the built heritage of Singapore to this day. The best-known is Cavenagh Bridge, which spans the Singapore River with its elegant lines and stout pillars. Commissioned by John Turnbull Thomson, the bridge, which was constructed by MacLellan and opened in 1870, has stood the test of time for almost 150 years. It is now used as a footbridge.

The former Telok Ayer Market in the central business district attracts lunchtime crowds from nearby offices to its food court, who are seemingly unaware of the illustrious history of this octagonal-shaped landmark. The aforementioned James MacRitchie was the engineer who designed the current building and arranged for its construction in cast iron by MacFarlane and Company in Glasgow.2 The market (more popularly known today as Lau Pa Sat or “Old Market” in Hokkien) opened in 1894.

The interior of Telok Ayer Market showing the cast iron by MacFarlane and Company in Glasgow, 1910s. The market (more popularly known today as Lau Pa Sat or “Old Market” in Hokkien) opened in 1894. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The interior of Telok Ayer Market showing the cast iron by MacFarlane and Company in Glasgow, 1910s. The market (more popularly known today as Lau Pa Sat or “Old Market” in Hokkien) opened in 1894. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Other examples of Scottish ironwork in Singapore include an ornate drinking fountain which, in the early part of the 20th century, was sited in front of Orchard Road Market but now graces a courtyard of Raffles Hotel; the balconies and verandahs in Raffles Hotel and the Singapore Cricket Club; the railings around Old Parliament House (since converted into The Arts House); and the ornamental balustrades protecting the sluice control mechanisms of MacRitchie Reservoir. The Scottish roots of Old Parliament House can be traced to its first owner, the Scottish merchant John Argyle Maxwell, who originally intended to use the building as his private residence.

More Scottish Architects

Archibald Alexander Swan, born in Glasgow in 1857, and James Waddell Boyd Maclaren, born in Edinburgh in 1863, were both Scottish trained civil engineers who together formed the partnership of Swan & Maclaren in 1890. The company – working with a team of architects − was responsible for many familiar landmark buildings in the city, such as the main building of Raffles Hotel, Stamford House, Teutonia Cub (now Goodwood Park Hotel), Adelphi Hotel and the former John Little building at Commercial Square (today’s Raffles Place).

Built in 1900, the former Teutonia Club on Scotts Road was designed by R.A.J. Bidwell of the Scottish architectural firm, Swan and Maclaren. The club was established to cater to the social and recreational needs of the German community in Singapore. The building was converted into the Goodwood Park Hotel in 1929. Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

Built in 1900, the former Teutonia Club on Scotts Road was designed by R.A.J. Bidwell of the Scottish architectural firm, Swan and Maclaren. The club was established to cater to the social and recreational needs of the German community in Singapore. The building was converted into the Goodwood Park Hotel in 1929. Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.Other buildings with strong Scottish connections include City Hall, designed in 1929 by the Scottish architect Alexander Gordon (which together with the adjoining Supreme Court is now the National Gallery Singapore); and the 1930s Tiong Bahru estate by fellow Scots James Milner Fraser, whose art deco-influenced design has stood the test of time. Fraser, incidentally, formed the Singapore branch of the Boys’ Brigade, thus leaving behind an intangible legacy.

The Municipal Building overlooking the Padang, c.1930. Designed by the Scottish architect Alexander Gordon in 1929, it was renamed City Hall in 1951. Together with the adjoining Supreme Court, it is now the National Gallery Singapore. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The Municipal Building overlooking the Padang, c.1930. Designed by the Scottish architect Alexander Gordon in 1929, it was renamed City Hall in 1951. Together with the adjoining Supreme Court, it is now the National Gallery Singapore. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.A Lasting Legacy

Connections to Scotland and the Scottish pioneers of early Singapore are indelibly imprinted on the face of Singapore in a plethora of place, street and district names, and also evidenced by much of its built heritage. It is a credit to the builders of modern Singapore that so much remains of the heritage introduced and inspired by Scottish merchants, engineers, doctors, administrators and soldiers – names that echo both the romantic misty glens as well as the mills, shipyards, factories and foundries of 19th-century Scotland.

It is not possible to explore every Scottish link to Singapore’s past in this short essay but streets have been named after Scottish officials such as Minto, Anderson, Elgin and Crawfurd; soldiers such as Haig and Neill; merchants like Bain, Angus, Hamilton, Gray, MacTaggart, Purvis and Campbell; engineers MacRitchie, MacPherson and Thomson; a newspaper editor, Still; doctors such as Cumming and Robertson; and businessman Read who was co-founder, along with several other Scots, of the first library and was a trustee of Raffles Institution, which itself was co-founded by a Scottish minister of religion, Dr Morrison, and based on principles of Scottish education. The Scottish influence in the names of Singapore streets is also seen in the use of the word Dunearn,3 connections to the church such as Kirk, towns and villages like Balmoral, Coldstream, Dundee and Dunbar, and Scottish rivers such as Ettrick and Yarrow. The list is extensive.

Scots also brought with them to Singapore their distinctive views on religion and education, and while their main aim was to make money from their colonial ventures, they were more than willing to develop places where they had made their home, even if they were only there temporarily. Churches, schools, libraries, freemasonry lodges, chambers of commerce, yacht clubs and of course the Singapore St Andrew’s Society, formed in 1836 and which continues to thrive to this day – all founded by Scots – brought the distinctive Scottish culture and tradition to the East.

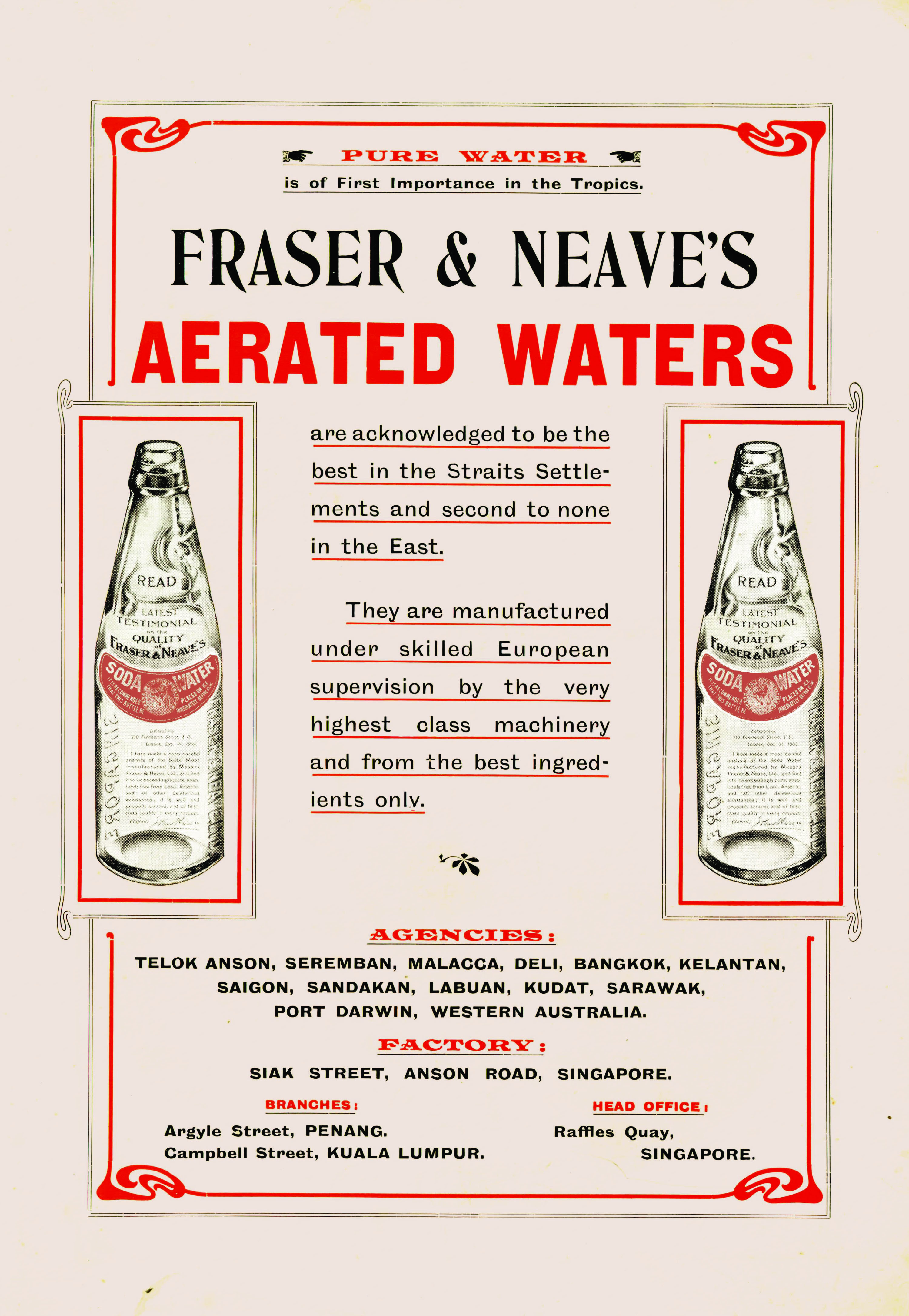

The Scottish legacy also extends to a number of major business conglomerates that created a foundation for the prosperity that continues to survive to this day in the East. Guthrie, one of Singapore’s first trading companies, and the household names of Fraser and Neave, P&O Shipping, Sime Darby, Standard Chartered Bank and HSBC, count among the many business enterprises founded by Scots.

An early advertisement by Fraser & Neave, founded by two Scotsmen, John Fraser and David C. Neave in 1883. Straits & F.M.S. Annual 1907–8. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Accession no: B03014243F).

An early advertisement by Fraser & Neave, founded by two Scotsmen, John Fraser and David C. Neave in 1883. Straits & F.M.S. Annual 1907–8. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Accession no: B03014243F).Then there are others who made contributions to the early development of Singapore but are no longer recognised in street or place names, one of whom was Alexander Laurie Johnston. Johnston was one of the earliest settlers in Singapore, having arrived between 1819 and 1820. He established A. L. Johnston & Co., one of the earliest trading houses in Singapore, and was instrumental in founding the Chamber of Commerce and becoming its first chairman. The first landing jetty at the harbour, built in 1856, was named Johnston’s Pier. It was later replaced with Clifford Pier, sited further along Collyer Quay, when the former could no longer cope with the increased sea traffic. The change in name incurred the ire of local merchants who boycotted the new pier’s opening on 3 June 1933.

And of course there is William Farquhar, whose Farquhar Street in the Kampong Glam area disappeared in 1994 after the roads in the area were realigned. Farquhar’s modest mausoleum near the entrance of the Grey Friars Churchyard in the city of Perth, Scotland, bears testament to his contributions to Singapore: “(Major General William Farquhar)… served as Resident in Malacca and afterwards at Singapore which later settlement he founded.”

Farquhar Street, named after William Farquhar, the first Resident and Commandant of Singapore, disappeared in 1994 after the roads in the area were realigned. All rights reserved, Singapore Street Directory. (1993, 17th edition). Singapore: SNP Corporation Ltd. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 SSD).

Farquhar Street, named after William Farquhar, the first Resident and Commandant of Singapore, disappeared in 1994 after the roads in the area were realigned. All rights reserved, Singapore Street Directory. (1993, 17th edition). Singapore: SNP Corporation Ltd. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 SSD).It is hoped that one day Farquhar’s name will join those of his many Scottish compatriots who did much to establish the early settlement of Singapore.

This essay contains extracts from the book, From Kilts to Sarongs: Scottish Pioneers of Singapore (2015), by Graham Berry. Published by Landmark Books, the book retails at S$59.90 and is available at major bookshops. It is also available for reference and loan at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and selected public libraries (Call nos.: RSING 959.570049163 BER and SING 959.570049163 BER).

Graham Berry was chief executive officer of the Scottish Arts Council from 2002 until his retirement in 2007. He currently resides in Singapore, where he serves on the board of several not-for-profit organisations, including the Substation and The Glasgow School of Art Singapore.

Graham Berry was chief executive officer of the Scottish Arts Council from 2002 until his retirement in 2007. He currently resides in Singapore, where he serves on the board of several not-for-profit organisations, including the Substation and The Glasgow School of Art Singapore.

REFERENCES

Beamish, J., & Ferguson, J. (1985). A history of Singapore architecture: The making of a city. Singapore: Graham Brash. (Call no.: RSING 722.4095957 BEA)

Bremner, D. (1869). The industries of Scotland: Their rise, progress, and present condition. Edinburgh: A. and C. Black. Retrieved from Internet Archive website.

Buckley, C.B. (1965). Anecdotal history of old times in Singapore, 1819–1867. Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya Press. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.57 BUC)

Chew, E.C.T. (1991). The foundation of a British settlement. In E.C.T. Chew & E. Lee (Eds.), A history of Singapore. Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 HIS)

Devine, T.M. (2004). Scotland’s empire and the shaping of the Americas, 1600–1815. Washington: Smithsonian Books. (Call no.: RCLOS 304.8411017521 DEV-[JSB])

Devine, T.M. (2006). The Scottish nation: 1700–2007. London: Penguin Books. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Devine, T.M. (2011). To the ends of the earth: Scotland’s global diaspora 1750–2010. London: Allen Lane. (Call no.: 909.049163 DEV)

Keay, J. (1991). The honourable company: A history of the English East India Company. London: HarperCollins. (Call no.: RSING 382.0941054 KEA)

Reith, G.M. (1985). Handbook to Singapore. Singapore; New York: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 REI)

Schelander, B. (1998). Singapore: A history of the Lion City. Honolulu: Centre for Southeast Asian Studies, School of Hawaiian, Asian and Pacific Studies, University of Hawaii at Manoa. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Turnbull C.M. (1995). Dateline Singapore: 150 years of the Straits Times. Singapore: Times Editions for Singapore Press Holdings. (Call no.: RSING 079.5957 TUR)

Vibart H.M. (1881). The military history of the Madras engineers and pioneers, from 1743 up to the present time. London: W.H. Allen & Co. Retrieved from Internet Archive website.

NOTES

-

Taylor, N.P. (2013, August). What do we know about Lawrence Niven, the man who first developed SBG? Gardenwise, 41, 2–3. Retrieved from Singapore Botanic Gardens website. ↩

-

The cast iron work was shipped out from Glasgow by P & W MacLellan. The cast-iron columns which support the structure, however, bear the maker’s mark of MacFarlane and Company. ↩

-

Dunearn is a composite word formed from two words: Dun and Earn. Dùn in Scottish Gaelic means “fort”. Loch Earn is a freshwater loch in the central highlands of Scotland. ↩