A Tale of Two Churches

Penang’s Armenian church was demolished in the early 1900s while the one in Singapore still thrives. Nadia Wright looks at the vastly different fates of these two churches.

The Armenian Church in Singapore as it looks today, with major alterations made around 1853 by George Maddock – the new steeple, new east portico and the flat roof. Courtesy of the Armenian Church.

The Armenian Church in Singapore as it looks today, with major alterations made around 1853 by George Maddock – the new steeple, new east portico and the flat roof. Courtesy of the Armenian Church.In Penang, the Armenian Apostolic Church of St Gregory the Illuminator was consecrated in 1824; nearly 12 years later in Singapore, another church bearing the same name was consecrated.

The futures of these two churches could not have been more different: while the Penang church was demolished in 1909, the Singapore church continues to exist to this day as the focal point for a small but thriving Armenian community, besides being a tourist attraction.

The Armenian Church in Penang

Around 301 AD, Armenia became the first country in the world to adopt Christianity as the state religion after the apostle Gregory converted its king, Tirdates III. This would cause much strife in later years as Armenia stood between two great Muslim powers: Persia and the Ottoman Empire. In the early 16th century, in his war against the Ottomans, the Persian king Shah Abbas razed the Armenian city of Julfa and deported some 25,000 Armenians to Persia (present-day Iran), mainly to his new capital Isfahan. He resettled most of the Armenians in an area that became known as New Julfa.

It was the descendants of these Persian Armenians, renowned for their acumen as merchants, who subsequently settled in India and later, Java, Penang and Singapore.1 As religion was integral to their lives, these diasporic merchants built churches in their new settlements as soon as they had the means. Penang and Singapore were no exception.

In 1786, Francis Light acquired the island of Penang from the Sultan of Kedah on behalf of the British East India Company (EIC) and established the settlement of George Town. The colony soon developed into a bustling entrepôt and attracted Armenian merchants from India and Java. Initially, these Armenians used the services of the Catholic and Anglican clergy for worship; however, as their numbers increased, they felt the need to have a church of their own.

In February 1821, an Armenian delegation met the British Governor of Penang, William Phillips, who asked for a plan and an estimate of costs. The sum needed was $7,000. Armenian philanthropist Carapiet Arrackell bequeathed $2,000 of this amount, and the community raised another $2,000. As they were short of $3,000, the Armenians petitioned Governor Phillips for a donation in 1822.

Phillips was of the view that hardworking Christian people would be an asset to the colony and to encourage more Armenians to settle in Penang, he donated $500 on behalf of the EIC, while recognising that this amount was much less than what the Armenians were anticipating. Indeed, this was a paltry sum compared with the $60,000 the EIC had donated towards the building of the Anglican St George’s Church in Penang. The directors of the EIC readily approved the donation seeing that it would encourage these hardworking and peace-loving people to settle in Penang.

The Armenian merchant Catchatoor Galastaun not only made good the shortfall, but additionally purchased a plot of land in September 1821 at Bishop Street between Penang Street and King Street. Construction of the church commenced under the supervision of British merchant and shipwright, Richard Snadden, and, in 1822, Bishop Abraham of Jerusalem officiated the laying of the foundation stone. In May 1824, the community bought the neighbouring site that had housed the government dispensary, thus enlarging the church compound and providing space to build lodgings for the priest.

On 4 November 1824, the church was consecrated in a service led by Bishop Jacob of Jerusalem and assisted by Reverend Iliazor Ingergolie, Penang’s first fulltime Armenian priest. The church was officially named the Armenian Apostolic Church of St Gregory the Illuminator. The local press described the church as the project of a “public spirited individual” (in reference to Galastaun), proclaiming it to be “one of the best proportioned and most elegant” buildings in Penang, adding that it “reflects much credit on the Armenian population”.2

Galastaun and his peers must have envisaged a much larger Armenian community settling in Penang when they pressed for a church. But this, unfortunately, did not materialise: Armenian numbers in Penang never surpassed more than 30. The success of rival Singapore spelled the end of the Penang church. After Singapore became the capital of the Straits Settlements in 1832 and surged ahead as its commercial centre, there was little incentive for Armenian entrepreneurs to sink their roots in Penang. The community shrank as members left, and the remaining few struggled to support the church.

Despite Penang’s tiny Armenian congregation, priests were sent out from Persia approximately every three years until 1885. After that, church services were held only when a priest visited Penang. The last was conducted in 1906 by Archbishop Sahak Ayvatian from the Mother church in Isfahan. On his visit, Archbishop Ayvatian discussed the future of the deteriorating church building with key members of the Armenian community. Whatever their decision, the church’s fate was sealed in February 1909 when decaying beams caused the collapse of a major balustrade, and large sections of the walls caved in. There was no option but to raze the building, retaining only the churchyard and parsonage.3

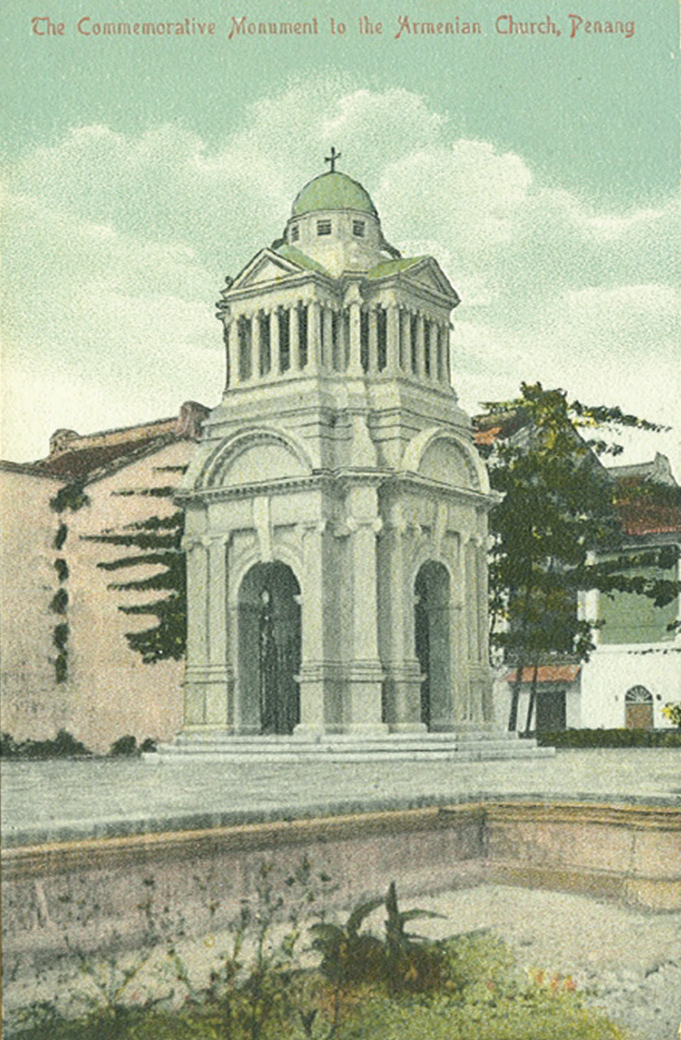

A postcard featuring the Armenian Commemorative Monument in Penang, c.1909.

A postcard featuring the Armenian Commemorative Monument in Penang, c.1909.As a memorial to the church, Armenians Joseph Anthony and Arshak Sarkies commissioned German architect Henry Neubronner to design a commemorative monument that was erected in 1909.4 Over the years, the monument as well as the garden surrounding it and the tombstones in the graveyard became neglected, leading the press to report that this made a mockery of those who had erected the memorial.

Arshak Sarkies (pictured here), along with Joseph Anthony, commissioned German architect Henry Neubronner to design a commemorative monument for the Armenian Church in Penang. The monument was erected in 1909. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Arshak Sarkies (pictured here), along with Joseph Anthony, commissioned German architect Henry Neubronner to design a commemorative monument for the Armenian Church in Penang. The monument was erected in 1909. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.In the late-1930s, the trustees of St Gregory’s Church in Singapore sold the site, on the instructions of the Mother church in Persia, and the monument was demolished. In August 1937, the 20 Armenians buried in the churchyard were re-interred in Western Road Cemetery (Penang’s municipal cemetery at the time) in a service conducted by Reverend Shamaian from Singapore.5 The money received from the sale of the church land was invested in the Catchatoor Galastaun Memorial Fund and managed by the church trustees in Singapore. The church’s silverware and its foundation plaque dated 1822 were given to the Armenian church in Singapore.6

Unfortunately, no image of the Armenian church in Penang has been found even though the building survived until 1909. Presumably it displayed all the customary features of an Armenian church – built of stone, with a vaulted ceiling, a dome and an east-facing chancel − as does the one in Singapore.7 References to the church building are scarce. Writing in 1839, Thomas Newbold commented that the Armenian chapel was one of the principal buildings in George Town, while James Low described it as “handsome”.8 Today, not even a marker indicates where this church once stood.

The Armenian Church in Singapore

The fate of the Armenian church in Singapore took a different trajectory altogether. Within a year of the establishment of a trading post in Singapore in 1819 by Stamford Raffles, Armenians began arriving. Initially, Reverend Iliazor Ingergolie travelled from Penang to conduct services for the Armenian community in Singapore. But after the community grew to around 20 in 1825, the Armenians wrote to the Archbishop in Persia asking that a priest be sent to serve their spiritual needs. In 1827, Reverend Gregory Ter Johannes arrived in Singapore.

View of Government Hill, the English Burial Ground and the Armenian Church in Singapore, in 1840. This view shows the original dome of the church with the gold cross on top and the pitched roof. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

View of Government Hill, the English Burial Ground and the Armenian Church in Singapore, in 1840. This view shows the original dome of the church with the gold cross on top and the pitched roof. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.At first, Reverend Ter Johannes conducted services in the premises of an Armenian merchant named Isaiah Zechariah, but soon, as in Penang, the community wanted its own church. In March 1833, Zechariah began petitioning Samuel Bonham, the Resident Councillor in Singapore, for a grant of land. Eventually a suitable site was agreed upon at the foot of Fort Canning. This land had earlier been granted to Dr Nathaniel Wallich to establish an experimental botanical garden, but this particular site facing Hill Street was left unused.9

Bonham sent the request for land along the bureaucratic path to Thomas Church, the Acting Governor in Penang, who then forwarded it to the government in Calcutta (Kolkata), hoping it would be approved as the Armenians were “peculiarly docile and diligent and in every respect desirable colonists”.10 In July 1834, approval for the land was granted; the welcome news reaching Singapore in September, whereupon the Armenians sprang into action.

The leading British architect of the time, George D. Coleman was commissioned to design the church and oversee its construction. Work commenced at a rapid pace. The foundation ceremony was conducted on 1 January 1835 by the Very Reverend Thomas Gregorian who travelled from Isfahan for the occasion, and the local priest Reverend Johannes Catchick.

The total cost of the construction, as well as accessories and regalia for the priest, amounted to $5,058.30. While the Penang church benefited from two wealthy donors, Singapore was not so fortunate. A public subscription was launched and, by mid-1836, some $3,120 had been donated, mostly by local Armenians. This left a shortfall of nearly $2,000 as well as the further $600 that was required to build a parsonage.

The paucity of donations from non-Armenians led to a sharp rebuke from The Singapore Chronicle newspaper, which had hoped that the meagre $370 donated by the Europeans and others would be supplemented; after all, Armenians had generously donated when the call was made to raise funds to build St Andrew’s Cathedral.11 But the plea largely fell on deaf ears. Fortunately, the 12 or so local Armenian families managed to raise the money, and also promised to cover ongoing costs.12

On 26 March 1836, the church was consecrated and dedicated to St Gregory, sharing the same name as the Penang church – the Armenian Apostolic Church of St Gregory the Illuminator. The Singapore Free Press declared it as one of Coleman’s “most ornate and best finished pieces of architecture”. The paper reported in glowing terms:

“This small but elegant building does great credit to the public spirit and religious feeling of the Armenians of this settlement; for we believe that few instances could be shown where so small a community have contributed funds sufficient for the erection of a similar edifice.”13

A painting of the Armenian Church in Singapore by John Turnbull Thomson, 1847. This view shows the original chancel and the second turret. All rights reserved, Hall-Jones, J. (1983). The Thomson Paintings: Mid-nineteenth Century Paintings of the Straits Settlements and Malaya (p. 43). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 759.2 THO).

A painting of the Armenian Church in Singapore by John Turnbull Thomson, 1847. This view shows the original chancel and the second turret. All rights reserved, Hall-Jones, J. (1983). The Thomson Paintings: Mid-nineteenth Century Paintings of the Straits Settlements and Malaya (p. 43). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 759.2 THO).Indeed, the church relied on a very small community (which never numbered more than 100 at its peak) to maintain it, as well as pay for the services of a priest. The burden of supporting the church was one continuously faced by the Armenians in Penang and Singapore. In Penang, the Anthony family supported the priest for many years, while in Singapore in the 1930s, that task was taken on by Mrs Mary Anne Martin.

In the 1840s and in 1853, the Singapore community raised money for major modifications to the roof and dome. Over the years, generous individuals further contributed to improvements and additions. For example, in 1861, Peter Seth donated the bell in the steeple, although this was not hung until the 1880s. In that same decade, Catchick Moses paid for the back porch and a new fence around the compound.

As in Penang, the priest lived in a parsonage within the church grounds. The original small building paid for by Simon Stephens was replaced in 1905 by a splendid Edwardian edifice commissioned by Mrs Anna Sarkies in memory of her husband, John Shanazar Sarkies.

The church, parsonage and grounds were damaged during World War II when the British military occupied the premises. After the war, the church trustees requested compensation to pay for repairs, but in the end the War Damages Commission paid only part of the claim. In the meantime, the church and parsonage deteriorated further. Local and visiting Armenians did their best to raise funds for renovations, their efforts augmented by generous donations from the Martin family and from church funds.

The last full service by a resident priest was held in 1938, although services were led by a deacon until the onset of the war in 1942. After the war ended, arrangements were made for priests to fly over from Australia, but these visits became more infrequent as the Armenian community shrank over the years. This did not mean the church lay idle. Since 1946, other Christian denominations have been allowed to worship at the Armenian church, while occasionally a visiting Armenian cleric would conduct a special service for the community.

By 1970, the congregation had diminished to about 10 people and the church was in dire need of repair. The government decided that the church was worth preserving and gazetted it as a National Monument in June 1973, thus securing its future. Augmenting this sense of permanence was the arrival of Armenian expatriates from America and Europe from the 1980s onwards who were posted to Singapore for work. Breathing new life to the small and ageing Persian Armenian community, these newcomers took an active interest in the church. The church was spruced up for its 150th anniversary in 1986, and Archbishop Baliozian from Sydney and Armenians from the region took part in the celebration. Over the years, the church has remained in the public eye through articles in the media and postage stamps released in Singapore (1978) and Armenia (1999).

After the 1990s, the size of the congregation further increased as Armenians, especially from Armenia and Russia, began to settle in Singapore. In 2016, the church trustees arranged for a priest to regularly visit from Calcutta to conduct services. The church also organises cultural events and has continued the practice of allowing weddings to be celebrated in its premises for a donation. All these activities, plus a steady flow of tourists, ensure that the church maintains a high public profile.

Unlike Penang’s Armenian church which has disappeared from living memory, its counterpart in Singapore is a national monument and tourist icon. More importantly, it remains the functioning church of one of Singapore’s smallest minorities.

Dr Nadia Wright, a retired teacher and now active historian, lives in Melbourne. She specialises in the colonial history of Singapore and Armenians in Southeast Asia. Her book, William Farquhar and Singapore: Stepping Out from Raffles’ Shadow, was published in May 2017.

Dr Nadia Wright, a retired teacher and now active historian, lives in Melbourne. She specialises in the colonial history of Singapore and Armenians in Southeast Asia. Her book, William Farquhar and Singapore: Stepping Out from Raffles’ Shadow, was published in May 2017.

NOTES

-

The Persian Armenians modified and shortened their names to sound more British, and most of them dropped the original “ian” ending. This resulted in surnames such as Anthony, Gregory, Martin and Stephens. ↩

-

Prince of Wales Island Gazette, 6 November 1824. ↩

-

Untitled. (1909, February 8). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Khoo, S.N. (2006). More than merchants: A history of the German-speaking community in Penang 1800s–1940s (p. 80). Pulau Pinang: Areca Books. (Call no.: RSEA 305.73105951 KHO) ↩

-

Unlike in Penang, and unique to Singapore, no Armenians were buried under the church aisle or the church grounds. Most of the tombstones laid out in the Garden of Memories were rescued from former cemeteries. ↩

-

The presence of the plaque at the Armenian Church in Singapore later led to a mistaken belief that it belonged to an earlier Armenian church there which had been demolished. ↩

-

HyeEtch. (1999, August 30). Formation of a national style. Retrieved from Hye Etch Arts & Culture website. ↩

-

Newbold, T.J. (1839). Political and statistical account of the British settlements in the Straits of Malacca (Vol. 1, p. 49). London: John Murray. Retrieved from BookSG; Low, J. (1836). A dissertation on the soil & agriculture of the British settlement of Penang, or Prince of Wales island, in the Straits of Malacca (p. 315). Singapore: Printed at the Singapore Free Press Office. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Dr Nathaniel Wallich (1786-1854) was responsible for establishing Singapore’s botanic gardens at Fort Canning. ↩

-

Thomas Church to the Secretary to Government, Fort William 17 June 1834, R. 2, Straits Settlements Records. ↩

-

Singapore. (1835, March 7). Singapore Chronicle and Commercial Register, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Translation of Minutes by the late Arshak Galstaun. ↩

-

Armenian Church. (1836, March 17). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩