Recipes for the Ideal Singaporean Female

From cooking, cleaning and becoming a good mother to outsourcing housework as careers for women took off. Sheere Ng charts how home economics lessons have evolved over the years.

Someone once asked me, “What did you learn to cook at home economics classes?”

In reply I proudly rattled off: fried rice with hotdog cubes, minced chicken on egg tofu, and spaghetti with sauce made with tomato ketchup. Imagine my embarrassment when a fellow (and older) food writer said that she had learned to make meat pies, mee siam and all sorts of kueh-kueh.

How did a 13-year-old get to make all these complex adult dishes at school while I was entrusted to cook with only processed and ready-to-eat ingredients? One crucial factor set us apart: time, or rather different periods of time.

I studied home economics in 1999, while she took the course back in the 1970s when it was known as domestic science, a name that was eventually replaced because it suggested a narrow focus on nutrition and sanitation.

Between the 1930s and 1997, home economics was taught in Singapore schools to train girls to be good homemakers. Depending on the era and the nation’s immediate needs, a “good homemaker” could mean different things – as defined by the prevailing syllabus set by the education authorities.

In the 1970s, for instance, being a good homemaker meant having the skills to just cook and clean. In the 1980s, it expanded to include being a good mother and raising a child. Then, in the 1990s, as more women joined the workforce, good homemakers became prudent consumers of outsourced and commercialised housework.

In “studying” home economics a second time around as research for this essay – reviewing textbooks, minister speeches, newspaper reports and oral histories – what became apparent was not just changes in cookery styles and ingredients over the years, but also official definitions of the “ideal” Singaporean woman.

Pre-independence: The Purpose of Home Economics

Home economics began in the United States in the late 19th century as domestic science. It was part of a larger movement to modernise the American diet through scientific cookery. The early champions of domestic science could be categorised into two camps: those who wanted to give women access to careers that had traditionally been dominated by men, and those who wanted to upgrade women’s status within its traditional realm by recasting domestic work as rational and efficient, and based on science and technology.1 Singapore clearly belonged in the latter category.

Domestic science, as it was referred to here before 1970, was first taught in English and mission girls’ schools in colonial Singapore. Students learnt practical domestic tasks such as laundry and needlework as well as European and Asian cookery. There was no standardised textbook, as Marie Ethel Bong, a former Katong Convent student remembered. Instead, the girls learnt the general principles of cookery from a foreign cookbook, and then copied the recipes from a blackboard before watching the nuns demonstrate them.2

A sewing class in progress at one of the convent schools, c.1950s. Diana Koh Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A sewing class in progress at one of the convent schools, c.1950s. Diana Koh Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Although many of the girls came from well-to-do families with servants, schools still insisted that their female students pick up domestic skills. “Even if you had servants at home, they felt that you should know how to do it yourself before you could instruct your amah in those days,” recalled Bong, who later became the principal of Katong Convent.3

There was no indication that the subject was taught to help the girls prepare for employment. Some, like the principal of CEZMS School, managed by the Church of England Zenana Missionary Society (renamed St Margaret’s Secondary School in 1949), even considered domestic science a non-academic subject. She said to the press in 1949, “Domestic science is perhaps more important than academic work where girls are concerned.”4

The opportunity to pursue a career in domestic science came from overseas in the 1950s. The United Kingdom and Australia offered overseas teaching scholarships to girls in Singapore, with the recipients returning just when government schools were allocating special rooms to teach domestic science.5 Ironically, these women professionals would play a role in furthering the government’s home economics agenda that sought to confine women to their traditional roles.

1970s: Training Girls to Cook, Clean – and Saw

The government began to see the value of home economics when women started to work outside the home. Singapore had been attracting foreign investments for labour-intensive industries since the 1960s. By 1970, the government had created more blue-collar jobs than men alone could fill, so it encouraged women to take up careers in traditionally male-dominated fields.6

Women working in the factory of Roxy Electric Company at Tanglin Halt, 1966. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Women working in the factory of Roxy Electric Company at Tanglin Halt, 1966. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.The call for women to contribute to the nation’s industrialisation was a success – between 1957 and 1980, the number of women in the manufacturing sector increased nearly 10 times7 – but it created a dilemma: working mothers were not passing on homemaking skills to their daughters who, upon reaching adulthood, were more likely to work than stay at home. Girls in traditional households had been taught how to cook and clean by their mothers, but the rise of working women meant that this transfer of homemaking skills was interrupted. The government saw this as a threat to the stability of the family unit – the basic building block of society.

The solution was to let home economics pick up where mothers had left off. Since 1968, the subject had been compulsory for secondary school girls, reinforcing the domestic role of women in society. But when blue-collar jobs became abundant with few takers, the Ministry of Education exhorted girls to pursue technical studies such as woodwork and metalwork so that they could pursue work that men did. The contradiction in these messages was stark: girls were told their place was in the home, but they were also required in the workforce.8

Despite the economic reality, the government still held archaic views of women’s roles. This is evident in the speeches of several ministers who espoused traditional gender roles during what was probably a very confusing time for Singaporean girls.

Speaking at a home economics exhibition in 1970, Minister for Education Ong Pang Boon made it very clear that homemaking was the responsibility of women:

“Home economics today cover a large and vital field. Our girls are taught to cook appetising, economical and well-balanced meals, to make clothes suitable for every occasion, to manage the home, and to look after the welfare of the family generally. These are skills which every girl should acquire. In the old days, they would have been taught by mother at home, but with the increasing tempo of urbanisation and industrialisation in Singapore, this basic training is often neglected at home.”9

Home economics has been compulsory for secondary school girls since 1968. But when blue-collar jobs became abundant with few takers, the education ministry exhorted girls to pursue technical studies such as woodwork and metalwork so that they could pursue the same jobs as men. This 1986 photo shows a class of girls at a woodwork lesson at Dunearn Secondary School. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Home economics has been compulsory for secondary school girls since 1968. But when blue-collar jobs became abundant with few takers, the education ministry exhorted girls to pursue technical studies such as woodwork and metalwork so that they could pursue the same jobs as men. This 1986 photo shows a class of girls at a woodwork lesson at Dunearn Secondary School. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Minister of State for Foreign Affairs Rahim Ishak did not single girls out explicitly, but left no doubt that the government believed that home economics was good for Singapore because “happy homes make a happy nation”. Against the backdrop of Singapore’s rising cost of living, he said that knowing how to cook, clothe and live well cheaply was essential. Speaking at the opening of a home economics facility at Anglican High School in 1973, he said, “… the introduction of home economics in school is vital if our future generations are going to run their homes properly”.10

Despite the emphasis on home economics, the government reversed its policy in 1977. To help students cope with the transition from primary to secondary school, the number of class periods in Secondary One was reduced. With less time to teach both home economics and technical studies, but still believing their relevance to girls, the government allowed female students to choose either subject, rather than study both. Throughout these changes, male students were trained only in technical studies.11

However, home economics grew to be unpopular among girls because it became associated with the less academically inclined. In the 1970s and 80s, primary school pupils who consistently failed their exams from Primary One to Three were transferred to the “monolingual stream” for slow learners where they would later study home economics or technical studies before moving into vocational training.12 Meanwhile, elite schools like Chinese High School and Nanyang High School removed the subject from their curriculum to make way for art lessons.13 These led some to believe that home economics was not for the intelligent, and that people who became homemakers were “dullards”.14

Member of Parliament for Jalan Kayu Hwang Soo Jin (front) viewing a home economics cookery class during the official opening of Hwi Yoh Secondary School in 1969. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Member of Parliament for Jalan Kayu Hwang Soo Jin (front) viewing a home economics cookery class during the official opening of Hwi Yoh Secondary School in 1969. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.In 1983, Minister for Education Tay Eng Soon revealed that only half of the girls in lower secondary classes studied home economics, and only 12 percent took it as an ‘O’ Level subject.15 Alarmed by the sharp drop, the ministry would again make home economics a compulsory subject for all girls in 1987.16

1980s: Homemakers are Mothers Too

Meanwhile, the hugely successful post-independence government policy of slowing down population growth by advocating two-children families gave way to the much maligned Graduate Mothers’ Scheme in 1984. The scheme essentially dangled tax benefits to encourage mothers with university degrees to have more children.17

This move stemmed from two pressing national issues of the day. First, population growth rates had slowed down over the years, and realisation set in that declining birth rates would have a severe impact on labour supply and, ultimately, economic growth. Second, there was a high ratio of unmarried graduate women in the population. Census figures in 1980 showed that two-thirds of graduate women were unmarried because men preferred less-educated wives. Graduate women were also having fewer children compared with their less educated counterparts due to changing aspirations and lifestyles.18

Then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew held the eugenicist view that smarter women were more likely to have intelligent children. Fearing that the lower birth rates among educated women would shrink the nation’s talent pool, he introduced the Graduate Mother’s Scheme to entice better-educated women to procreate, but not before he lectured Singaporeans at the 1983 National Day Rally. In typically forthright fashion he said:

“If you don’t include your women graduates in your breeding pool and leave them on the shelf, you would end up a more stupid society… So what happens? There will be less bright people to support dumb people in the next generation. That’s a problem.”19

To the dismay of women’s rights advocates, traditional views of the man as the head of the household and women’s role as wives and mothers were reinforced by the government. Speaking at the 50th anniversary of St Nicholas Girls School in 1983, Minister for Education Tay Eng Soon said:

“I want now to speak on a subject which is overlooked because of our emphasis on academic excellence. This is particularly pertinent to a girls’ school. I refer to the fact that most of your students will one day marry and become mothers regardless of their academic achievements or career. This is their natural and proper role in life.”20

The following year, the ministry announced that home economics would become a compulsory core subject by 1987 for all girls in lower secondary classes. They would not be able to opt out or elect to study a technical course. A revised syllabus would also be introduced to help girls see “the importance of nurturing and strengthening a family” and to “enable them to have a sensible outlook on social and national problems”, according to one newspaper report.21

Home economics textbooks had all the while focused on cleaning, cooking and sewing. But this changed with the introduction of the 1987 Home Economics Today textbook for Secondary Two students, which pared down these topics to make way for nine chapters on child-rearing – significantly more than an earlier textbook that taught “mothercraft” in just nine pages.22

The syllabus corresponded with the government’s agenda for women to be mothers. It was clear that apart from being a source of much needed talent, women were also encouraged to produce more children to augment the talent pool.

To prepare the students for motherhood, the 1987 textbook taught everything from breastfeeding to how to deal with childhood ailments, and was more comprehensive in content than a typical handbook for expectant mothers. This was a huge difference from previous home economics textbooks that advocated family planning between the 1970s and mid-1980s when there was a national effort to keep a lid on a population boom that was threatening to overwhelm public infrastructure.23 Naturally, the new home economics policy did not sit well with women’s rights advocates who charged that it was sexist and unfavourable towards girls who had career plans.

Why Only Women Homemakers?

Voices of opposition rippled in the press. Many were upset that the new home economics policy was saddling girls with homemaking responsibilities. Instead of excusing boys from learning how to do household chores or raising a child, schools should be re-educating the young “to look upon marriage and homemaking and childcare as a shared responsibility”, wrote Lena Lim, founding president of the Association of Women for Action and Research (AWARE).24

Re-education could mean offering home economics to anyone interested regardless of gender, proposed a forum writer in The Straits Times, so that girls who wanted to pursue other interests could opt out, as should unwilling boys if they would only become grudging helpers at home.25 Whichever form re-education might take, the dissenters agreed that young people must be persuaded to accept a change in gender roles. If Singapore was serious about alleviating the unmarried graduate women problem, it had to “take a fresh view of marriage and the ideal wife” wrote Singapore Monitor editor Margaret Thomas in September 1984.26

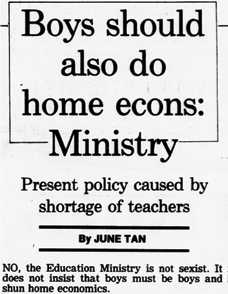

In 1984, the government announced that home economics would become a compulsory subject by 1987 for all girls in lower secondary. Although the government supported the idea of boys learning home economics, there were insufficient teachers; boys were therefore encouraged to learn home economics at extra-curricular clubs in schools. The Straits Times, 27 November 1984, p. 1.

In 1984, the government announced that home economics would become a compulsory subject by 1987 for all girls in lower secondary. Although the government supported the idea of boys learning home economics, there were insufficient teachers; boys were therefore encouraged to learn home economics at extra-curricular clubs in schools. The Straits Times, 27 November 1984, p. 1.The following month, some 428 people, including engineers, lawyers, and teachers signed a petition to urge the education ministry to rethink the policy of making home economics compulsory for girls. The petition argued that it would deny girls the chance to study technical subjects in secondary school, and eventually hamper their chances of enrolling for technical courses in polytechnics.27

Although the government would not be persuaded, and all girls would go on to study home economics in lower secondary from 1987 onwards, there appeared to be some effort to present a fairer distribution of housework in at least two of the textbooks under the new syllabus.

In the 1986 Home Economics Today for Secondary One students, one chapter titled “Happy Family Life” showed a picture of a father preparing food in the kitchen with his family, and accompanying text that read, “If members of a family help one another to get the work done, the home will certainly be a happier place to live.”28

Home economics textbooks published in the 1980s tried to correct traditional gender roles by including images of families spending time together cooking and eating. All rights reserved, Viswalingam, P. (1986). Home Economics Today 1E (p. 14) Singapore: Curriculum Development Institute of Singapore. (Call no.: YR 640.76 HOM).

Home economics textbooks published in the 1980s tried to correct traditional gender roles by including images of families spending time together cooking and eating. All rights reserved, Viswalingam, P. (1986). Home Economics Today 1E (p. 14) Singapore: Curriculum Development Institute of Singapore. (Call no.: YR 640.76 HOM).This was a stark difference from New Home Economics, a 1983 textbook that portrayed only women cleaning or cooking, completely leaving out their husbands from the responsibility of homemaking.

An illustration of a woman washing up in the kitchen in a 1983 textbook was indicative of societal norms at the time – the books seldom featured men doing housework. All rights reserved, Hamidah Khalid & Siti Majhar. (Eds.). (1983). New Home Economics (Book 1) (p. 29) Singapore: Longman Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 640.7 NEW).

An illustration of a woman washing up in the kitchen in a 1983 textbook was indicative of societal norms at the time – the books seldom featured men doing housework. All rights reserved, Hamidah Khalid & Siti Majhar. (Eds.). (1983). New Home Economics (Book 1) (p. 29) Singapore: Longman Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 640.7 NEW).However, this attempt to present a fairer distribution of housework should not be seen as a sign that the government was serious in tackling gender inequality. After all, the home economics textbooks had an insignificant male audience and were unlikely to persuade many future husbands to chip in at home.

Although the education ministry said that boys would learn home economics when there were adequate teaching resources, this would not happen until 1997 – more than 10 years after it was first announced.29

What was far more effective in giving women respite from the chores of homemaking, and perhaps even salvaging some marriages, was the advent of modern home appliances. The sale of rice cookers, microwave ovens and washing machines took off and became increasingly affordable for the new dual-income households. Home economic textbooks in the late 1980s also began to explain the use of electrical appliances. Some of them were as basic as an oven toaster, suggesting their novelty at the time.30

Working women became enthused by these “electric servants”, and home economics teachers began attending workshops that demonstrated the use of home appliances. Teachers also started exploring the use of factory-processed frozen, canned and bottled foods during home economic classes, and waxed lyrical about their visits to Sunshine Bakery and Kikkoman soya sauce factory in the Home Economics Teachers’ Association (HETA) quarterly.31 Their readiness to embrace labour-saving products foreshadowed yet another syllabus revamp in the coming decade.

Post-1990s: From Home Producers to Consumers

Home economics textbooks in the late 1990s conveyed a different notion of homemaking. Not only were cooking and sewing simplified, but the childcare chapters that had been added in 1987 to prepare girls for motherhood were also removed. These changes were introduced after home economics became a compulsory subject for both boys and girls in 1997, and the syllabus was tweaked to complement the new policy.32 What brought about this sea change 10 years later?

Unlike earlier home economics textbooks that seldom showed men playing a part in household chores, a textbook from the 1987 syllabus showed a father bathing his baby. All rights reserved, Viswalingam, P. (1987). Home Economics Today 2E (p. 24) Singapore: Curriculum Development Institute of Singapore. (Call no.: YR 640.76 HOM).

Unlike earlier home economics textbooks that seldom showed men playing a part in household chores, a textbook from the 1987 syllabus showed a father bathing his baby. All rights reserved, Viswalingam, P. (1987). Home Economics Today 2E (p. 24) Singapore: Curriculum Development Institute of Singapore. (Call no.: YR 640.76 HOM).Since the 1980s, housework was becoming increasingly commercialised and commoditised, available for purchase as products or services. More families were eating out instead of cooking, shopping for clothes rather than sewing them, and buying washing machines to do their laundry. By the time home economics was offered to both boys and girls in 1997, the definitions of homemaking had changed. Wives (and husbands) were not expected to be skilful homemakers like their mothers were, since they could just “buy their way” out of household chores.

The 1997 edition of Home Economics Today acknowledged these modern trends as it discussed the options of eating out and convenience foods, and teaching students how to feed themselves without having to actually cook their own meals. It also explained clothing care labels and advertising techniques, instead of the finer points of fabric weaves and brooms.33 Compared with its predecessors, the 1997 textbook showed a more balanced portrayal of male and female in relation to domestic work, likely in deference to Singapore’s pledge at the 1995 United Nations World Conference on Women to not gender-type roles in school instructional materials.34

Another new development was the proliferation of foreign domestic workers. The government first introduced foreign maids as a childcare solution in the 1970s so that mothers would go to work, but the move gathered steam only from the 1990s. The 1987 Home Economics Today textbook included advice for working parents on using the services of childcare centres, caregivers – and maids. The last option proved to be so popular that the number of foreign domestic workers in Singapore ballooned from just 5,000 in 1978 to 100,000 in 1997.35

This transfer of caregiver roles from mothers to others, and the transformation from household production to consumption, rendered many homemaking instructions from the old syllabus excessive and even irrelevant for 21st-century families. Taking the cue from new consumer lifestyles, home economics was renamed Food and Consumer Education in 2014 (while still remaining a compulsory subject for boys and girls in lower secondary), with its syllabus focusing mainly on good consumer decisions and money management.

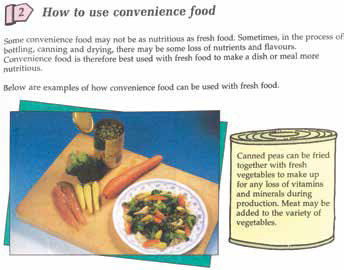

In the 1990s, home economics textbooks took into consideration busy lifestyles by offering tips on how to use modern convenience foods in home-cooked dishes and suggested dining out occasionally. All rights reserved, Chong, E.S.H., et al. (1997). Home Economics Today Secondary 2 (p. 19) Singapore: Curriculum Planning & Development Division, Ministry of Education. (Call no.: RSING 640.76 HOM).

In the 1990s, home economics textbooks took into consideration busy lifestyles by offering tips on how to use modern convenience foods in home-cooked dishes and suggested dining out occasionally. All rights reserved, Chong, E.S.H., et al. (1997). Home Economics Today Secondary 2 (p. 19) Singapore: Curriculum Planning & Development Division, Ministry of Education. (Call no.: RSING 640.76 HOM).I am a product of the 1997 syllabus, designed with the expectation that I could one day opt out of gender-typed work as my mother did, and outsource homemaking to processed foods, appliances or to other women with lesser means. Indeed, I never pursued cooking outside the classroom as our Filipino helper at home knew better than to add tomato ketchup to spaghetti.

It was only as an adult that I re-acquainted myself with the kitchen when food took on an important dimension in my work and at home. I had only been as “ideal” as the government’s recipe for a Singaporean woman until I created my own.

Sheere Ng is a food writer and researcher with an interest in the intersections of food, immigration and identity. She has an MLA in Gastronomy from Boston University and runs a writing studio called In Plain Words.

Sheere Ng is a food writer and researcher with an interest in the intersections of food, immigration and identity. She has an MLA in Gastronomy from Boston University and runs a writing studio called In Plain Words.

NOTES

-

Shapiro, L. (1986). Perfection salad: Women and cooking at the turn of the century (pp. 26–46). New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. (Not available in NLB holdings); Stage, S., & Vincenti, V. B. (1997). Rethinking home economics: Women and the history of a profession (pp. 79–95). New York: Cornell University Press. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Tan, L. (Interviewer). (1982, December 7). Oral history interview with Noel Evelyn Norris [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 000221/18/16, p. 163]; Chua, C.H.J. (Interviewer). (1993, February 9). Oral history interview with Marie Ethel Bong [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 001390/64/20, pp. 190–194]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Chua, C.H.J. (1993, February 9). Oral history interview with Marie Ethel Bong [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 001390/64/16, p. 155]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Girls to learn cooking. (1949, February 26). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Career for home economists in Singapore. (1987, August). HETA news, 2, p. 3. Singapore: The Association. (Call no.: RSING q640.7 HETAN). Ministry of Culture. (1973, June 30). Speech by Mr A Rahim Ishak, Minister of State for Foreign Affairs, at the opening of the home economics building and extension of the school tuckshop at the Anglican High School on Saturday, 30th June 1973 at 9.00 a.m (p. 2). Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy. (2016). Foreign domestic workers in Singapore: Social and historical perspectives (p. 4). Retrieved from Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy website; Kho, E.M. (2013). The construction of femininity in a postcolonial state: girls’ education in Singapore (p. 57). New York: Cambria Press. (Call no.: RSING 371.822095957 KHO) ↩

-

Wong, K., & Leong, W.K. (Eds.). (1993). Singapore women: Three decades of change (p. 89) Singapore: Times Academic Press. (Call no.: RSING 305.42095957 SIN) ↩

-

Ministry of Culture. (1970, April 27). Speech by Minister for Education, Mr Ong Pang Boon, at the opening of the home economics exhibition – Victoria Memorial Hall on 27th April, 1970 at 5.15 p.m. (p. 1). Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Ministry of Culture, 30 Jun 1973, p. 2. ↩

-

Kho, 2013, pp. 60–61; Ministry move to help sec 1 students. (1976, December 28). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ministry of Culture. (1978, May 31). Paper presented by Dr Ahmad Mattar, Minister-in-Charge of the Industrial Training Board, at the Singapore Malay Teachers’ Union’s Seminar on “New challenges in Singapore’s education system” on Wednesday, 31 May 1978, at 0930 hours, in DBS Auditorium (p. 7). Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website; Pereira, B. (1983, October 10). Easier lessons for the slow learners. Singapore Monitor, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Boey, C. (1983, September 5). It’s not kid stuff – appreciate their art. Singapore Monitor, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ministry of Culture, 30 June 1973, p. 2. ↩

-

Ministry of Culture. (1983, September 3). Speech by Dr Tay Eng Soon, Minister of State for Education, at the 50th anniversary of St Nicholas Girls’ School at the Neptune Theatre Restaurant on Saturday, 3 September 1983 at 7.30 p.m (p. 2). Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Thomas, M. (1984, September 9). Girls: In a class by themselves. Singapore Monitor, p. 16. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lee, K.Y. (2000). From third world to first: The Singapore story, 1965–2000: Singapore and the Asian economic boom (p. 140). New York: HarperCollins Publishers. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.57092 LEE) ↩

-

Lee, 2000, pp. 135–140; Policies for the bedroom and beyond. (2015, March 23). Today, p. 28. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ministry of Culture, 3 Sep 1983, p. 2. ↩

-

Singapore Monitor, 9 Sep 1984, p. 16. ↩

-

Hamidah Khalid & Siti Majhar. (Eds.). (1983). New home economics (Book 2) (pp. 18–27). Singapore: Longman Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 640.7 NEW); Viswalingam, P. (1987). Home economics today 2E (pp. 3–58). Singapore: Curriculum Development Institute of Singapore. (Call no.: YR 640.76 HOM) ↩

-

Hamidah & Siti, 1983, p. 25; National Library Board. (2014). National family planning campaign is launched. Retrieved from HistorySG. ↩

-

Boys need to know about the home too. (1984, November 18). Singapore Monitor, p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Why not enlighten boys on home economics too? (1984, December 7). The Straits Times, p. 21. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore Monitor, 9 Sep 1984, p. 16. ↩

-

Alfred, H. (1984, November 24). 428 petition against compulsory home econs. The Straits Times, p. 21. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Viswalingam, P. (1986). Home economics today 1E (p. 14) Singapore: Curriculum Development Institute of Singapore. (Call no.: YR 640.76 HOM) ↩

-

Ministry of Communications and Information. (1986, March 19). Speech by Dr Tay Eng Soon, Minister of State for Education, at the home economics seminar: “New Dimensions” organised by the Home Economics Teachers’ Association at the Mandarin Hotel on Wednesday, 19 March 1986, at 2.30 p.m. (p. 4). Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Viswalingam, 1987, pp. 173–179. ↩

-

Electrolux. (1984, March). HETA news, 10. Singapore: The Association. (Call no.: RSING q640.7 HETAN); Visit to the Kikkoman factory. (1986, September). HETA news, 2, 9. Singapore: The Association. (Call no.: RSING q640.7 HETAN); Trip to “rise and shine”. (1988, June). HETA news, 1, 9. Singapore: The Association. (Call no.: RSING q640.7 HETAN) ↩

-

Boys-, girls-only courses open to all. (1996, March 30). The Straits Times, p. 25. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Chong, E.S.-H., & Kee, M.H., et al. (1996). Home economics today. Secondary 1 Special/Express/Normal (Academic) (p. 57). Singapore: Curriculum Development Institute of Singapore. (Call no.: RSING q640.76 HOM); Chong, E.S.H., et al. (1997). Home economics today. Secondary 2 special/express/normal, academic (pp. 16, 119, 140). Singapore: Curriculum Planning & Development, Ministry of Education. (Call no.: RSING 640.76 HOM); Viswalingam, 1987, pp. 135–137, 199; Hamidah & Siti, 1983, pp. 13, 102. ↩

-

Ministry of Information and the Arts. (1995, September 6). Statement by Mr Abdullah Tarmugi, Acting Minister for Community Development at the Fourth United Nations World Conference on Women, Beijing, People’s Republic of China, 4-15 September 1995, delivered at the plenary session at 8.00 p.m. on 6 September 1995 (p. 4). Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, 2016, pp. 4–5, 21; Viswalingam, 1987, p. 41. ↩