Blooming Lies: The Vanda Miss Joaquim Story

Is the Vanda Miss Joaquim a human-made hybrid or a happy accident? In this cautionary tale, Nadia Wright, Linda Locke and Harold Johnson recount how fiction becomes truth when it is repeated often enough.

While doing research on the Armenian community in Singapore back in the 1990s, Australian historian Nadia Wright read an account of how the daughter of a prominent Armenian family in Singapore, Agnes Joaquim1 (Ashken Hovagimian), had stumbled upon a never-before-seen orchid bloom by accident in the family garden.

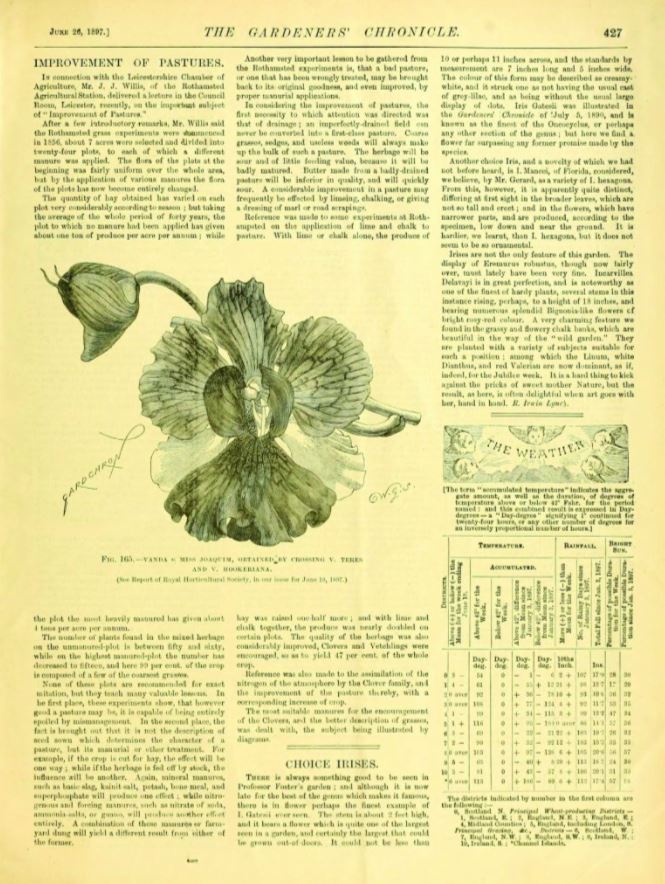

In the authoritative The Gardeners’ Chronicle, published on 24 June 1893, however, Henry Nicholas Ridley, the first Director of the Singapore Botanic Gardens (1888−1911) stated unequivocally that Agnes Joaquim had crossed two different orchids, the Vanda Hookeriana with the Vanda teres and produced the orchid which he later named Vanda Miss Joaquim.2 Intrigued as to why Ridley’s account had been replaced by a tale of chance discovery in various stories about the flower in Singapore, Wright decided to investigate.

The Birth of a Bloom

In 1893, Agnes Joaquim, or possibly her brother Joe (Joaquim P. Joaquim), showed Henry Ridley a new orchid. After carefully examining the bloom, having it sketched, and preserving a specimen in the herbarium of the Botanic Gardens, Ridley sent an account of the orchid’s origin and appearance to The Gardeners’ Chronicle, a respected English horticulture periodical founded in 1841. He wrote:

“A few years ago Miss Joaquim, a lady residing in Singapore, well-known for her success as a horticulturist, succeeded in crossing Vanda Hookeriana, Rchb. f., and V. teres, two plants cultivated in almost every garden in Singapore. Unfortunately, no record was kept as to which was used as the male. The result has now appeared in the form of a very beautiful plant, quite intermediate between the two species and as I cannot find any record of this cross having been made before, I describe it herewith.”3

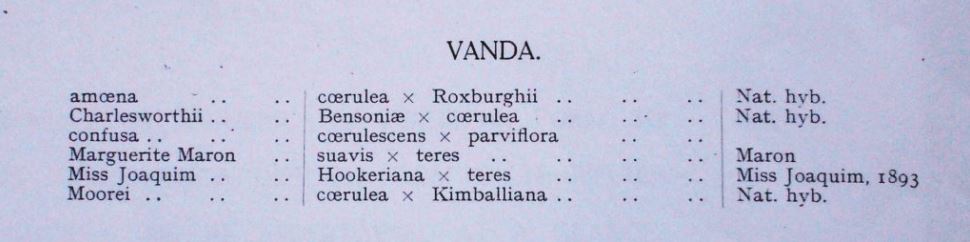

In an 1894 paper delivered to the prestigious Linnean Society in England, Ridley reiterated that Vanda Hookeriana had been “successfully crossed” with V. teres, Lindl., “producing a remarkably handsome offspring, V. x Miss Joaquim”. This paper was published unaltered in 1896.4 Ridley, who lived to be 100 years old, never wavered in his statement. When Isaac Henry Burkill (Ridley’s successor at the Botanic Gardens) checked all of Ridley’s herbarium specimens and redid the labels, he saw no reason to dispute Ridley and recorded Joaquim as the creator.

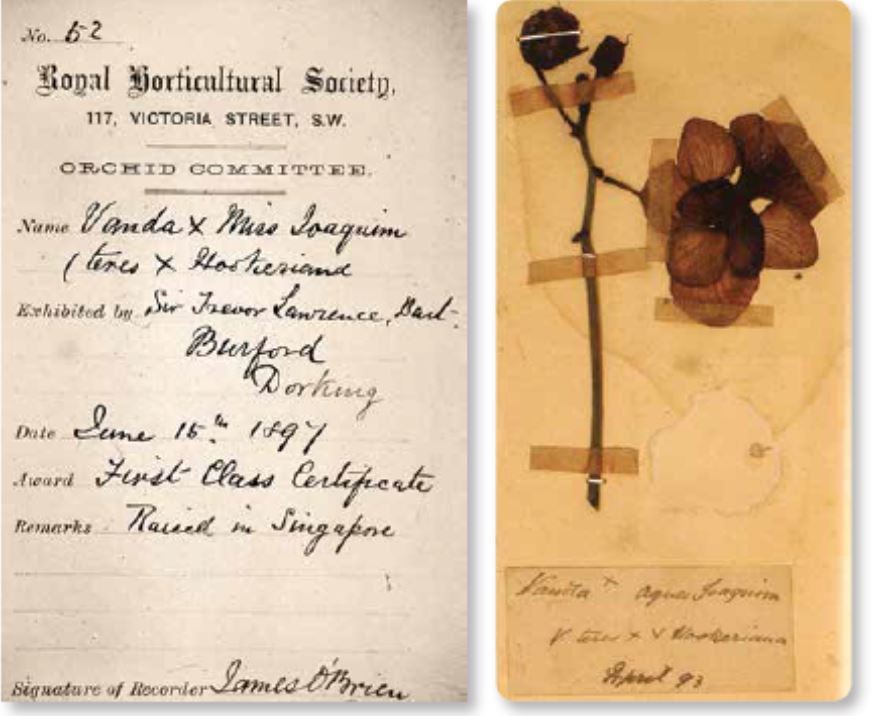

Ridley sent cuttings of Vanda Miss Joaquim to Sir Trevor Lawrence, President of the Royal Horticultural Society and one of the world’s leading orchidists, where it was nurtured in his orchid house at Burford Lodge, in Dorking, England. Flowering for the first time in Europe in 1897, Vanda Miss Joaquim was displayed at the Royal Horticultural Show in London, winning a First Class Certificate. In describing the event, The Gardeners’ Chronicle noted that “the plant was obtained from a cross between V. teres and V. Hookeriana some years ago by Miss Joaquim at Singapore”.5

(Right) A detail from the Vanda Miss Joaquim specimen sheet of the first spike of flowers received in April 1893 by the Singapore Botanic Gardens. The flower was the same one described by Henry Ridley in The Gardeners’ Chronicle in June 1893. The label beneath the specimen is Ridley’s handwriting. Courtesy of the Singapore Botanic Gardens Herbarium.

In Singapore, Joaquim’s orchid debuted at the 1899 Flower Show. The Straits Times commented that “one of the most noticeable flowers was the orchid Vanda Miss Joaquim, named after Miss Joaquim and raised by that lady”.6 The Singapore Free Press confirmed Joaquim’s achievement, reporting that “Miss Joaquim showed a hybrid which has been named after her, that she has, after repeated trials, succeeded in cultivating”.7

From 1893 until 1981, the orchid was accepted, with few exceptions, as a hybrid bred by Joaquim. Robert Rolfe, editor of The Orchid Review and an authority on orchid hybrids, placed Vanda Miss Joaquim among the 106 cultivated hybrids created in 1893. Subsequent issues of The Orchid Review, The Gardeners’ Chronicle and other leading contemporary horticultural journals reiterated the fact that Joaquim had crossed the parent orchids, as did all the editions of the authoritative Sander’s Complete List of Orchid Hybrids.

Sowing the First Seeds of Doubt

In 1931, The Straits Times announced that a new hybrid orchid – the Spathoglottis Primrose – had been produced in Singapore. It was the first orchid raised using the new technique of germinating seeds in a sterile culture. This orchid was described as the second hybrid to be produced in Malaya or, as the newspaper playfully added in parentheses, “the first if Vanda Miss Joaquim came into being as the result of a happy accident”.8 No reason was offered for this speculation and the mischievous aside was not taken up.

Richard Eric Holttum, who was Director of the Botanic Gardens between 1925 and 1942 and again from 1946 to 1949, accepted Ridley’s description, as did his later successors Murray Ross Henderson (1949–54) and John William Purseglove (1954–57). In Hawaii, Harold Lyon (the first Director of Honolulu’s Foster Botanical Garden), who was involved with the propagation of Vanda Miss Joaquim there, believed Ridley.

Agnes Joaquim’s nephew Basil J.P. Joaquim, a prominent lawyer in Kuala Lumpur, corroborated Ridley’s view and was cited inThe Straits Times in 1951 as saying “this hybrid was not discovered in the garden… [but was the result of [an] artificial pollination… performed by my unmarried aunt, Miss Agnes Joaquim”.9 Articles published in local newspapers also regarded the orchid as an artificial hybrid created by Joaquim.]

(Middle) Richard Eric Holttum, Director of the Singapore Botanic Gardens (1925–1942 and 1946–1949), was an orchid hybridiser himself and he regarded the Vanda Miss Joaquim as Singapore’s first artificial hybrid orchid. Courtesy of Singapore Botanic Gardens.

(Right) Humphrey Morrison Burkill, Director of the Singapore Botanic Gardens (1957–1969), alleged that artificial orchid hybrids were not produced in Singapore until 1928. He said that among plants used in creating hybrids was the “natural hybrid Vanda Miss Joaquim” which he described as a “delightful accident of nature”. Image source: Sharp, I., & Lum, S. (Eds.). (1996). A View from the Summit: The Story of Bukit Timah Nature Reserve (p. 29). Singapore: Nanyang Technological University and the National University of Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 333.78095957 VIE).

However, at the 1963 World Orchid Conference held in Singapore, Humphrey Morrison Burkill, who was appointed Director of the Singapore Botanic Gardens in 1957, sowed the seeds of dispute, alleging that artificial orchid hybrids were not produced in Singapore until 1928. He added that among the plants used in creating hybrids was the “natural hybrid Vanda Miss Joaquim” which he described as a “delightful accident of nature”.10

Burkill’s claims not only contradicted those of his father Isaac Burkill (Director of Botanic Gardens, 1912–25) and other former directors, but also cast doubt on Ridley’s character. Ridley had not only officially reported the genesis of the Vanda Miss Joaquim in 1893 but also successfully created orchid hybrids himself, in 1896 and 1902. Yet, the younger Burkill gave no supporting evidence for his puzzling assertion.

References to Vanda Miss Joaquim’s origin decreased in the late 1960s and during the 1970s, reflecting declining interest in the orchid. While some in Singapore referred to it as an artificial hybrid, others began to repeat Humphrey Burkill’s allegation that it was a natural hybrid. Like him, none gave any reason for doubting Ridley’s official account.

The Discovery Myth

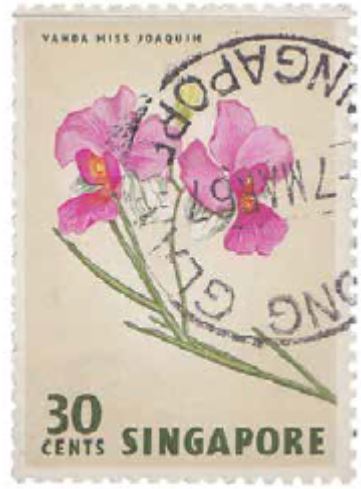

On 15 April 1981, Vanda Miss Joaquim was declared Singapore’s national flower. While fame was assured for the orchid, Agnes Joaquim’s true role was tossed aside when newspaper reports of the day described the flower as a natural hybrid which she had chanced upon in her garden. When a nephew of Agnes Joaquim, Basil E. Johannes, was invited to Singapore for the launch of the National Flower Week in July 1981, he further contributed to the confusion by claiming that Agnes Joaquim had discovered the flower – not only contradicting what his cousin Basil J.P. Joaquim said in 1951, but also Ridley.

Arriving at Changi Airport on 21 July from Perth, Australia, where he had been living for over two decades, the 88-year-old Johannes declared to the reporter who interviewed him that “Aunt Agnes found the flower one morning [in 1893] when she was loitering in the garden. She was so excited that she took it to the director of the Botanic Gardens straightaway”.11 Local newspapers ran with Johannes’s story, alleging that Vanda Miss Joaquim was a natural hybrid and making no mention of Ridley’s original account.

In his book on the Vanda Miss Joaquim published in 1982, Teoh Eng Soon further enshrined Johannes’s story in print, embellishing it with more detail: “One morning while Agnes was loitering alone in the garden she came upon a new orchid flower nestled in a clump of bamboo… Agnes could not contain her excitement. Straightaway she took it to the Director of the Singapore Botanic Gardens.”12

Arshak Galstaun, President of St Gregory’s Board of Trustees, which looked after the affairs of the Armenian Church in Singapore, and an old friend of Johannes’s was dismayed by this turn of events. In fact, he said so at Teoh’s book launch and wrote to the media refuting it.

Galstaun regarded Ridley’s statement in 1893 that “no record was kept as to which of the plants was used as the male” as evidence that Joaquim had been experimenting with orchid hybrids for some time. He was certain that Ridley would not have made that comment if the hybrid had been created naturally.13

Believing Johannes’s recollections to be based on hearsay and pure conjecture, Galstaun reasoned that the “positive written record of a scientist of Mr Ridley’s stature” should hold sway over the reminiscences of an elderly person. But his views published in the Malayan Orchid Review in 198214 were brushed aside, and again it was claimed that the orchid was a natural hybrid.15

There was no further opposition to this fictitious story: an example of when something is repeated often enough, it sometimes becomes accepted truth. Subsequent newspaper mentions of the orchid said it was a natural hybrid. Even when the centenary of the orchid took place in 1993, there was no reference to Ridley’s account.

A diorama at the Singapore History Museum and a brochure on the National Orchid Garden stated that the orchid was discovered by Miss Agnes Joaquim, as did a display board at the Singapore Botanic Gardens as recently as 2016. All of that reinforced the view that Singapore’s national flower had popped up serendipitously in Joaquim’s garden one day.

Debunking the Myth

In 2000, Nadia Wright wrote an article in the Malayan Orchid Review, maintaining that Agnes Joaquim had crossed the orchid as Ridley had recorded. Explaining why the discovery story was false, she declared it was time to set the record straight.16 Although Wright based her reassessment on publicly available historical evidence, her article was criticised by those who believed that the orchid was a natural hybrid discovered by chance.

Aiming to discredit Wright’s research, the detractors echoed Teoh Eng Soon’s spurious claim that “nearly every orchidist since [1893] believed that [Joaquim] had discovered a natural hybrid”.17

The debate continued until 2007. In her book on Singapore’s Armenians published in 2003, Wright reiterated her stand, adding that Joaquim was the first woman in the world to breed an orchid.18 That book and Wright’s subsequent article in 2004 came under fire, but no credible evidence to refute Ridley’s findings was offered in return.19

Although Wright explained why the account of the orchid’s origin written by a respected botanist and orchid expert, and accepted by other experts should be believed over confused and unsubstantiated speculations, her views were summarily dismissed by the authors of a book on Vanda Miss Joaquim.20

The authors accepted Teoh’s reconstructed account as factual, declaring that Teoh was right simply because he “described the event” in detail.21 Yet Teoh could not provide concrete proof of how he became privy to his information, including details such as Joaquim was “alone” when she found the orchid “nestled in a clump of bamboo”. The Vanda Miss Joaquim needs “full sunlight and plenty of air movement” in order to thrive, and thus it was most unlikely to have grown in the shade of a bamboo clump as alleged.22

The book repeated Teoh’s claim that Johannes was right, declaring that he was “the only living person to have met her [Agnes Joaquim]”.23 The authors, however, failed to mention that the 88-year-old Johannes was born in 1893, the year Vanda Miss Joaquim originated, or that Johannes had spent his infancy in Java, only coming to Singapore to live in 1901 when he was eight years old: two years after Joaquim’s death. Johannes would have met Joaquim only when the family was visiting Singapore and when he was very young (he was only six years old when she died). Members of the extended Joaquim family were stunned by Johannes’s remarks to the press.

Whatever the case, these facts cast serious doubt on the credibility of Johannes’s testimony, as does an oral history interview he gave to the National Archives in July 1981 which showed that his recollections were neither consistent nor accurate.

Basil Johannes’s older brother John, who was born 10 years earlier in 1883, told a very different story. In the 1890s, John Johannes attended Raffles Institution and no doubt lived with his grandmother and Joaquim at the family home. He was 16 years old in 1899 and more likely than his younger brother to have had first-hand knowledge of the orchid. In later years when John Johannes walked past a flower shop displaying Vanda Miss Joaquim orchids, he would cross his two forefingers and proudly tell his daughter Hazel that her grand-aunt had bred the orchid.

Hazel Locke’s (nee Johannes) account of her father’s actions was scathingly dismissed by various people who insisted that Johannes’s claim that the orchid grew in a clump of bamboo was “a report of an observation”.24 How the proponents of the discovery theory reached these conclusions is unknown.

It is likely that Basil Johannes was confusing Agnes Joaquim’s “discovery” with a much later event. One day in the 1930s while walking in Malaya, his cousin Basil Joaquim came across an unusual orchid, which he sent to the Director of the Botanic Gardens to see if it were a new orchid.

Discrediting Ridley

To push for acceptance of Basil Johannes’s account, its supporters turned on Ridley. They suggested that Ridley’s statement about Agnes Joaquim crossing the orchid was “allegorical rather than factual”, or that it was based on an “assumption”.25

But Ridley was known to be a careful observer and recorder. Had Joaquim found the orchid, Ridley would have written it up accordingly as he had done with other natural hybrids. Besides, the wording of Ridley’s article reinforces the fact that Joaquim had produced the orchid. Had she just stumbled upon it by chance, there would be no need for Ridley to mention the fact that she had failed to record the pollen parent. Ridley would gain nothing by concocting a false claim; indeed, his reputation as an orchid expert would have been at stake, not to mention his position as the first Director of the Botanic Gardens.

Critics tried to discredit Ridley by claiming that he did not know how to hybridise orchids. They questioned his specific expertise as his interests ranged “from agriculture to ghosts”, implying that he had only a superficial knowledge about many subjects. They dismissed Ridley’s expert account in The Gardeners’ Chronicle because it was written after he had lived “in Singapore only 4–5 years and before acquiring the expertise he had in later years”.26

In truth, Ridley was an orchid expert when he arrived in Singapore in 1888. As a Fellow of the Linnean Society, his prolific output covered 10 papers on orchids. These included his detailed observations of orchid self-pollination and an influential paper on “The Nomenclature of Orchids” presented at the 1886 British orchid conference. Indeed, England’s leading orchidists of the time, such as Frederick Burbidge and James Veitch, turned to Ridley with queries on orchid fertilisation. Yet his account was rejected in favour of that of Basil Johannes who admitted that he knew nothing about growing plants.

Ridley’s account was further dismissed because Joaquim had not kept close records of her work. The aforementioned Robert Rolfe lamented that earlier hybridists too had not kept records as to which was the seed parent. However, their work has not been dismissed because of this supposed failing.

It has been claimed that because Ridley did not describe how the seeds were germinated in his report, Joaquim could not have made the cross. But then, such information was not included in other articles on hybrids in The Gardeners’ Chronicle; they simply gave the names of the hybridiser, the parent orchids, and a detailed botanical description of the new flower. This was exactly what Ridley’s article did.

Indeed, biologist Joseph Arditti, a strong supporter of the discovery myth, noted that William Herbert, a pioneer in hybridisation, had given “no details regarding his germination method”.27 Yet, inexplicably, Arditti accepted Herbert’s hybrid as genuine, but not Joaquim’s.

The Plot Thickens

It has been suggested that Agnes Joaquim would not have known how to germinate seeds and that successful methods of germination had been developed only after her death. This is far from true. In fact, Vanda Miss Joaquim was one of 106 artificial hybrids created in 1893. Joaquim’s achievement was not an anomaly – she was doing in Singapore what others were already doing in Britain and elsewhere.

Information on germination was readily available in books as well as in horticultural journals. Besides, it has been suggested that Joaquim had sown the seeds onto a base of coconut dust, from where they germinated.28 Curiously, it was inferred that if the pollination was done by a bee, then the seeds could germinate, but if the pollination was done by Joaquim, the seeds could not have done so.

There was no end to the efforts to disparage Joaquim. Her critics pointed out that Joaquim did not breed any other orchids, apart from the one she had been falsely credited with. Claiming that hybridisers tended to make several crosses in their lifetimes, they concluded that she could not possibly have created the Vanda Miss Joaquim. But the fact is all hybridisers start with one cross. What further weakened the critics’ spurious claims is that the very source they cited reported that half of all breeders in that study produced only one hybrid.29

As they did with Ridley, Joaquim’s detractors doctored quotations to belittle her role. For example, they quoted The Straits Times of 12 April 1899 as reporting that Joaquim “succeed [sic] in cultivating” the Vanda Miss Joaquim, but downplayed the word “cultivating” in this context to mean merely “growing”.30

Elsewhere, they omitted Ridley’s reference to Joaquim by claiming that he “only wrote that the cross was between Vanda Hookeriana Rchb.f. and V. teres” when in fact he had specifically reported that Joaquim had “succeeded in crossing” these two orchid species.31

They also misquoted Singaporean pioneer breeder John Laycock, who said the question as to how Agnes had succeeded in germinating the seed into a flowering plant “must now forever remain unanswered”.32 Laycock’s words were rewritten into something quite different from what he had intended – that the question of whether or not Joaquim bred the orchid “must now forever remain unanswered”.33

If the Vanda Miss Joaquim is a natural hybrid as alleged, then what was the agent of the pollination? Could it be carpenter bees, as it has been claimed before? But there is no evidence in history of these bees ever creating another Vanda Miss Joaquim. And there never have been any reports of naturally occurring Vanda Miss Joaquim orchids being found anywhere.34

Besides, if bees had done the pollinating, Ridley would have said so. In his observations, Ridley carefully distinguished between an insect visiting a flower and pollination by a human. Noting that carpenter bees did the “greatest amount of pollination in Singapore”, he compiled a list of plants they pollinated.35 He did not record carpenter bees as visiting or pollinating either Vanda Hookeriana or Vanda teres, although he noted that such bees did assist in the fertilisation of other orchids.36

Arditti insisted that “all orchid scientists and knowledgeable orchid growers believe that Vanda Miss Joaquim is a natural hybrid”.37 But he did not substantiate this sweeping statement. Indeed, to the contrary, Harold Johnson’s review of literature shows that until 1981, almost all publications accepted Vanda Miss Joaquim as an artificial hybrid and only a few after 1963 suggested differently.38

It is worth remembering that Botanic Gardens director Richard Holttum, who closely reviewed his predecessor Isaac Burkill’s work, regarded Vanda Miss Joaquim as an artificial hybrid. In 1928, Holttum quoted Ridley’s original report, commenting on the skill and care with which Agnes Joaquim had raised the plant and describing it as “her orchid”.39 Again in 1972, he quoted Ridley’s report as evidence of the orchid’s origins.40

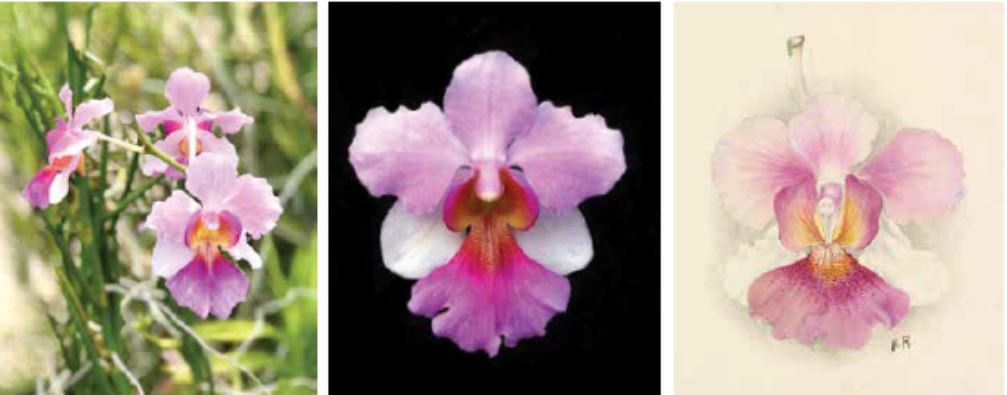

(Middle) A close-up of a Vanda Miss Joaquim. Courtesy of National Parks Board.

(Right) A painting of the Vanda Miss Joaquim that won Sir Trevor Lawrence, President of the Royal Horticultural Society, the First Class Certificate at the 1897 Royal Horticultural Flower Show. Drawn by artist Nellie Roberts in 1897, it is simply titled “Miss Joaquim Agnes”. FCC/RHS. Image source: RHS Lindley Collections, The Royal Horticultural Society.

Getting it Right – Finally

Ridley was widely respected for his role in establishing the Singapore Botanic Gardens as a reputable attraction and, in 1955, was described by historian Sir Richard Winstedt as “the man whose influence on Malayan history is second only to that of Raffles”.41 Yet, after 1981, Ridley’s pronouncement on the origins of the Vanda Miss Joaquim became sidelined. Although contemporary orchid experts accepted Ridley’s statement that the orchid was deliberately created, the discovery story was perpetuated by a television drama, online articles, in books and even in scholarly journals.

In 2007, Arditti ans Hew continued to claim that Vanda Miss Joaquim was a natural hybrid but yet again provided no evidence.42 In a final attempt to set the record straight, Harold Johnson and Nadia Wright collaborated on a book in 2008 that documented the orchid’s true origins.43 Although the book elevated public awareness of the subject, it was still not sufficient to convince officialdom to accept that Joaquim had hybridised the orchid.

In 2009, The Straits Times repeated that Agnes Joaquim had bred the orchid, but in news reports published in 2011, 2012 and 2015, it moved to a more neutral position without attributing credit to her. However, signs of change began to appear. For example, in 2011, a sample question from the Singapore citizenship quiz asked who had bred the orchid. The correct answer was Agnes Joaquim.

Finally, in 2015, after careful deliberation, Joaquim was inducted into the Singapore Women’s Hall of Fame in recognition of her hybridisation of the orchid. Hazel Locke (Basil Johannes’s niece) accepted the award on Joaquim’s behalf. The award was presented by Halimah Yacob, then Speaker of Parliament (and currently President of Singapore).

But the journey towards correcting history was not over yet. In 2016, matters came to a head after Hazel Locke’s daughter, Linda Locke, came across a display board at the Singapore Botanic Gardens that failed to recognise Joaquim’s role. The younger Locke embarked on further research to evaluate the conflicting arguments put forward by various people and was able to confirm that the evidence presented by Johnson and Wright was indisputable.

Locke persisted in her efforts to correct official records of Singapore history and managed to convince the National Heritage Board (NHB) to conduct its own review of all historical source materials. Only then did NHB, together with the National Parks Board, arrive at the conclusion that Agnes Joaquim had indeed crossed the parent plants to create Vanda Miss Joaquim. NHB and the Singapore Botanic Gardens amended their official records in 2016.

This news was brought to the attention of other government agencies – the National Library Board, for instance, corrected its articles about the orchid on Singapore Infopedia, its online encyclopedia − and in September 2016, The Straits Times ran a full-page report accepting that Agnes Joaquim was responsible for creating the hybrid orchid.44

Truth had finally triumphed, but its vindication was hard won, with a war of words and various parties taking different sides since the late 1950s. Much ado over a trivial matter, some may say. However, when the bloom in question is Singapore’s national flower, it is important that its correct history is told. This is all the more timely as we commemorate the 125th anniversary of the Vanda Miss Joaquim in 2018.

Agnes Joaquim’s lineage can be traced to the diasporic Armenian community who sank roots in Singapore soon after the settlement’s founding in 1819. Joaquim’s grandparents were Isaiah Zechariah, one of the founders of Singapore’s Armenian Apostolic Church of St Gregory the Illuminator – more simply known as the Armenian Church – and Ashkhen Arathoon, after whom Agnes Joaquim was named.

Her parents were Parsick Joaquim, an Armenian from Madras, and Urelia Zechariah, a Singapore-born Armenian. Parsick Joaquim arrived in Singapore around 1840 and worked as a merchant and trader. Together with Simon Stephens, he founded Stephens & Joaquim in 1849.

In 1852, Parsick Joaquim married Urelia Zechariah and lived on Hill Street near other Armenian families and the church. His business thrived, and in 1861, the family moved to a mansion overlooking Tanjong Pagar, which he named Mt Narcis, after his eldest son. When the mansion was demolished in 1901, the carriageway leading to the house was named Narcis Road.

(Left) Photo of Agnes Joaquim on a locket that once belonged to her, with an inscription of her name on the reverse side. The locket is now in the possession of Linda Locke, her great grand-niece. Courtesy of Linda Locke.

(Left) Photo of Agnes Joaquim on a locket that once belonged to her, with an inscription of her name on the reverse side. The locket is now in the possession of Linda Locke, her great grand-niece. Courtesy of Linda Locke.(Right) Agnes Joaquim died of cancer on 2 July 1899 at the age of 45. Her tombstone is found within the grounds of the Armenian Church in Singapore. It was originally located at Bukit Timah Cemetery. Her tombstone bears the inscription “Let her own works praise her”. Courtesy of Prem Singh.

Parsick Joaquim died unexpectedly in 1872, leaving his wife to raise 11 children, the youngest of whom was three years old. Fortunately, he left the family well provided for.

Agnes Joaquim, born on 7 April 1854, did not marry and was no doubt an immense help to her widowed mother, although their workload eased when the four youngest sons were sent to boarding school in England. Joaquim led a busy social life, attending various balls and festivities. However, it appears she was a strict woman in her later years, shooing her young nieces and nephews out of sight whenever guests arrived at the house.

Joaquim was a skilled and artistic needlewoman. She embroidered a beautiful altar cloth for the Armenian Church, and at the 1891 Flower Show, she was complimented for her most attractive bouquet composed of orchids and delicate grasses.

However, it was in the garden that Joaquim excelled, putting her fingers and mind to work. She won an impressive number of prizes in the annual flower shows before finally making her mark in history with her hybrid, Vanda Miss Joaquim. Exhibited at the annual Flower Show in April 1899, the Vanda Miss Joaquim won First Prize for the rarest orchid, and more importantly, recognition for her years of work.

However, Joaquim was not destined to live long. She developed cancer and her condition took a turn for the worse when she contracted pneumonia. She died on 2 July 1899 at the relatively young age of 45. Local newspapers reported Joaquim’s death, describing her as the sister of “respected townsman” Joe Joaquim, her younger brother, and an eminent lawyer and Municipal Commissioner.

Joaquim was buried in Bukit Timah Cemetery, and when the grounds were acquired by the government, her tombstone was one of those rescued and moved to the Armenian Church grounds. Today, it rests in the Garden of Memories in the church grounds, with a pot of orchids – the Vanda Miss Joaquim, naturally – on either side. The epitaph on the tombstone reads: “Let her own works praise her”, a reminder of the enduring legacy Agnes Joaquim left behind.

The hybridisation of a plant involves two steps. First, pollination takes place during which pollen is transferred from the male flower to the female flower to create a seed. Second, germination occurs in which the seed develops into a plant. Whether a hybrid is artificial or natural depends on how the pollination occurred. If the transfer of pollen is done by a person, the resulting hybrid is termed “artificial”. If it is done by agents of pollination such as insects, birds or by the wind, it is termed “natural”.

Dr Nadia Wright, a retired teacher and now active historian, lives in Melbourne. She specialises in the colonial history of Singapore and Armenians in Southeast Asia. Her book, William Farquhar and Singapore: Stepping Out from Raffles Shadow, was published in May 2017.

Dr Nadia Wright, a retired teacher and now active historian, lives in Melbourne. She specialises in the colonial history of Singapore and Armenians in Southeast Asia. Her book, William Farquhar and Singapore: Stepping Out from Raffles Shadow, was published in May 2017.

Linda Locke is a great grand-niece of Agnes Joaquim. She is a former advertising CEO and the co-author of the recently released children’s book: Agnes and her Amazing Orchid.

Linda Locke is a great grand-niece of Agnes Joaquim. She is a former advertising CEO and the co-author of the recently released children’s book: Agnes and her Amazing Orchid.

Harold Johnson is an orchid enthusiast. The second edition of his book with Nadia Wright entitled Vanda Miss Joaquim: Singapore's National Flower & the Legacy of Agnes & Ridley will be published in late 2018.

Harold Johnson is an orchid enthusiast. The second edition of his book with Nadia Wright entitled Vanda Miss Joaquim: Singapore's National Flower & the Legacy of Agnes & Ridley will be published in late 2018.

NOTES

-

Joaquim is pronounced joe/ah/kim/ with the accent on joe. ↩

-

Today, the orchid’s botanic name has been changed to Papilionanthe Miss Joaquim although it is still commonly called Vanda Miss Joaquim. ↩

-

Ridley, H. N. (1893, June 24). Vanda Miss Joaquim. The Gardeners’ Chronicle, 13, p. 740. Retrieved from Biodiversity Library website. ↩

-

Ridley, H. N. (1896). Mr. Ridley on the Orchideae and Apostasiaceae of the Malay Peninsula. Journal of the Linnean Society, Botany, p. 356. ↩

-

Orchid Committee. (1897, June 19). The Gardeners’ Chronicle, 21, p. 410. Retrieved from Biodiversity Library website. ↩

-

The flower show. (1899, April 12). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The flower show. (1899, April 12). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The article later described Vanda Miss Joaquim as an artificial hybrid. New orchids for Malaya (1931, August 4). The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

On the margin. (1951, April 5). The Straits Times, 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Burkill, H. M. (1963). The role of the Singapore Botanic Gardens in the development of Orchid Hybrids (p. 14). Singapore: Straits Times Press. (Call no.: RCLOS 584.15 BUR-[RFL]) ↩

-

Lim, H. K. (1981, July 23). “Miss Joaquim fails to greet nephew at gates”. The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Teoh, E. S. (1982). A joy forever: Vanda Miss Joaquim Singapore’s national flower (p. 31) Singapore: Times Books International. (Call no.: RSING 584.15095957 TEO) ↩

-

The question of the male parent was only resolved in 2015 by Dr Gillian Khew who determined that it was Vanda Hookeriana. See Feng, Z. (2015, July 10). Vanda Miss Joaquim mystery solved. The Straits Times, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Galstaun, A. C. (1982). Letter to the editor. Malayan Orchid Review, 16, pp. 52–53. Singapore: Straits Times Press. (Call no.: RSING 584.15 MOR) ↩

-

Goh, C. J. (1982). Dr Goh replies. Malayan Orchid Review, 16, pp. 53–54. Singapore: Straits Times Press. (Call no.: RSING 584.15 MOR) [Note: The editor of the journal was Teoh Eng Soon.] ↩

-

Wright, N. H. (2000). The origins of Vanda Miss Joaquim. Malayan Orchid Review, 34, pp. 70–73. (Call no.: RSING 584.15 MOR) ↩

-

Teoh, (1982), p. 32; Yam T. W., Arditti, J., & Hew C. S. (2004). The origin of Vanda Miss Joaquim. Malayan Orchid Review, 38, p. 93. (Call no.: RSING 584.15 MOR) ↩

-

Wright, N. H. (2003). Respected citizens: The history of Armenians in Singapore and Malaysia (p. 150). Middle Park, Vic.: Amassia Publishing. (Call no.: RSING 305.891992 WRI) ↩

-

Wright, N. H. (2004). A re-examination of the origins of Vanda Miss Joaquim. Orchid Review, 112 (1259), pp. 292–298; Human Flower Project. (2005, August). Miss Agnes’s big little secret. Retrieved from Human Flower Project website; Arditti, J., & Hew, S.H. (2005) Letter to the editor. The Orchid Review, 113 (1263), pp. 176–177. ↩

-

Hew, C.S., Yam, T.W., & Arditti, J. (2002). Biology of Vanda Miss Joaquim (pp. 222–224). Singapore: Singapore University Press. (Call no.: RSING 584.4095957 HEW) ↩

-

Hew, Yam & Arditti, 2002, p. 41. ↩

-

Hew, Yam & Arditti, 2002, p. 179; Miss Joaquim’s nephew coming for Flower Week. (1981, July 19). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Hew, Yam & Arditti, 2002, p. 46. ↩

-

Yam, Arditti & Hew, 2004, p. 93; Hew, Yam & Arditti, 2002, p. 224. ↩

-

Hew, Yam & Arditti, 2002, p. 223; Arditti & Hew, 2005, p. 176. ↩

-

Arditti & Hew, 2005, p. 176. ↩

-

Arditti, J. (1992). Fundamentals of orchid biology (p. 43). New York: Wiley. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Notes on monthly meetings. (1957). Malayan Orchid Review, 5 (2), p. 30. (Call no.: RSING 584.15 MOR); Yeoh, B.C. (1959). Kinta weed. Malayan Orchid Review, 5, p. 81. (Call no.: RSING 584.15 MOR) ↩

-

Citing Yeoh Bok Choon’s List of Malayan Hybrids, 1963, p. v, which mentioned that of 62 individual breeders, 31 produced only one hybrid. ↩

-

Arditti & Hew, 2005, p. 177. ↩

-

Yam, Arditti & Hew, 2004, p. 92. ↩

-

Laycock, J. (1949, January). Vanda Miss Joaquim. Philippine Orchid Review, 2, p. 3. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Hew, Yam & Arditti, 2002, pp. 49, 52. ↩

-

Claims that a hybrid found growing in garden in Johor Baru is evidence that Vanda Miss Joaquim is a natural hybrid are misleading. That hybrid was not a Vanda Miss Joaquim. Although the parent plants grew in the garden, the bee did not create the orchid from them, instead it cross-pollinated Vanda Hookeriana and Vanda Miss Joaquim. ↩

-

Ridley, H.N. Various Notes Zoological and Botanical: Fertilization Notes, Australian Joint Copying Project, M. 773, reel 44, frame 336–7. ↩

-

Ridley, H.N. Notebook 1891–1896 Fertilization Notes, AJCP, M. 771, reel 42, frame 255. Also see Ridley, H.N. (1905, July). On the fertilization of the grammatophyllum. Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 44, pp. 228–229. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Arditti, J. (2005, April 26). You say orchid, I say Joaquim. Retrieved from dsng.net website. ↩

-

Johnson, H. J. (2004). Vanda Miss Joaquim. Malayan Orchid Review, 38, pp. 99–107. (Call no.: RSING 584.15 MOR) [Note: Linda Locke added more to that list of literature in 2017]. ↩

-

Holttum, R. E. (1928). Vanda Miss Joaquim. Malayan Naturalist, 2 (1), pp. 22, 24. (Call no.: RRARE 574.9595 MAL; Microfilm no.: NL 6582) ↩

-

Holttum, R. E. (1972). And comments. The Orchid Review, 80 (951), p. 168. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Purseglove, J. W. (1955, December 10). The Ridley Centennial, mss. ↩

-

Arditti, J., & Hew, C.S. (2007). The origins of Vanda Miss Joaquim (pp. 290-291). In Orchid Biology. Reviews and Perspectives, IX. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Johnson, H., & Wright, N. (2008). Vanda Miss Joaquim: Singapore’s national flower & the legacy of Agnes & Ridley. Singapore: Suntree Media. {Call no.: RSING 635.9344096957 JOH) ↩

-

Zaccheus. F. M. (2016, September 7). Vanda Miss Joaquim’s namesake gets official credit as creator. The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩