Chinese Renaissance Architecture

This unique style of architecture only reigned for five decades in China, yet several buildings in Singapore still bear the hallmarks of this hybrid form, says Julian Davison.

There have been several “Chinese Renaissances” in the history of the Middle Kingdom – depending on which authority one consults. For the historian, the Han (206 BCE–CE 220), Tang (618–907) and Song (960–1279) dynasties, can each, in their own way, claim to be the Chinese equivalent to the Renaissance in the West that took place between the end of the 14th and the beginning of the 17th centuries.

Chinese Renaissance Deconstructed

When it comes to architecture, however, the term “Chinese Renaissance” generally refers to the output of a group of young Chinese architects in the 1920s and ’30s who returned to China after a period of overseas study, seeking to reconcile what they had learnt of modern building technologies with a stylistic idiom that reflected traditional Chinese aesthetic sensibilities – a kind of architectural equivalent of “Socialism with Chinese characteristics”.

Perhaps the best known of these architects was Lu Yanzhi (1894–1929), a graduate of Cornell University, who designed the Sun Yat Sen Mausoleum in Nanjing (completed 1929). Another was Dong Dayou (1899–1975), an alumnus of Columbia University, who wrote an article in the English-language T’ien Hsia Monthly in 1936 extolling the achievements of this pioneer generation of Chinese architects:

“A group of young students went to America and Europe to study the fundamentals of architecture. They came back to China filled with ambition to create something new and worthwhile. They initiated a great movement, a movement to bring back a dead architecture to life: in other words, to do away with poor imitations of Western architecture and to make Chinese architecture truly national.”1

Given the historical background of this period, the Chinese Renaissance, as an architectural movement, can be seen as part of a wider call for renewal and revitalisation of Chinese society and culture taking place at the time. This came on the back of more than half a century of foreign interference in China’s affairs, following the disastrous Opium Wars of the mid-19th century that ceded Hong Kong to Britain and established treaty ports in China.

The Christian Influence

But if the term Chinese Renaissance perfectly captures the spirit of those times and the ambitions of the young architects who sought, quite literally, to build a new China, the origins of the movement can be traced back to the architecture of Christian missions stations a quarter of a century earlier.

Although the intent of the mainly American Christian architects who designed these buildings was by and large the same as the Chinese architects who followed them a generation later – namely, to find a middle ground between Eastern and Western building typologies – their motivation was quite different. These Christian architects were not so much interested in a renewal and rejuvenation of Chinese society and culture, but rather were more intent on luring potential Chinese converts away from their traditional belief systems – Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism and ancestral worship – and persuading them to embrace a Christian god.

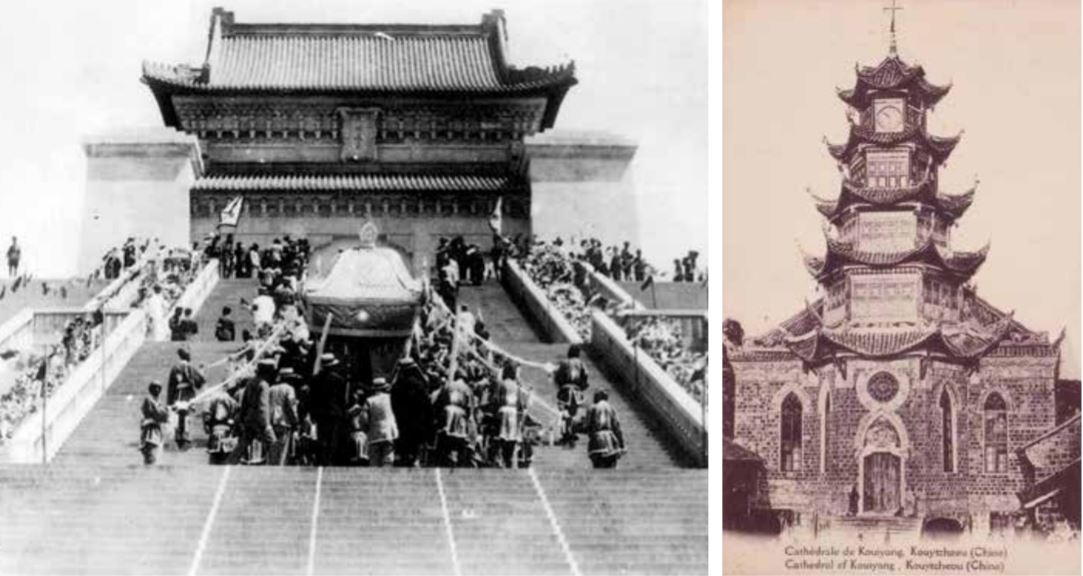

One of the earliest examples of an East-West architectural pairing in China is a remarkable structure – a church with a belfry in the form of a Chinese pagoda – erected by Catholic missionaries in Guiyang, southwest China, in the mid-1870s. Named St Joseph’s Cathedral, it is, perhaps, no more than a case of cultural appropriation – making do with the materials available at the time – than a purposeful attempt to create a new architectural style that took the design aesthetics of the West and infused them with an Eastern sensibility.

(Right) St Joseph’s Cathedral in Guiyang, China, erected by Catholic missionaries, mid-1870s. It represents one of the earliest examples of an East-West architectural pairing in China. Courtesy of Julian Davison.

By the turn of the century, however, Christian missionaries in China were acknowledging the fact that churches built in an overtly European style – Gothic was the architecture of choice back then – could seem alienating and even intimidating to their Chinese audience. And not only churches, but also schools, hospitals, orphanages and other buildings associated with the typical mission station in China in the late 19th century.

Jeffrey Cody, a leading historian in the field of Christian missionary architecture in China, writes: “As they [the missionaries] sought to educate, proselytize and convert Chinese, they tried to strike a culturally harmonious chord with their buildings.”2

One of the first missions to adopt this approach was the Canadian Methodist Mission in Chengdu, China, which started adding Chinese-style roofs to its West China Union University campus buildings from around 1910 onwards. As a Foreign Missions Report from 1914 explained, five years of deliberations had “resulted in the adoption of an Orientalized Occidental type of architecture. The buildings… express the harmony and spirit of unity that pervades the entire institution and the purpose to unite in one the East and West”.3

Before long, other missions followed suit. Between 1911 and 1917, there were at least four other large-scale building projects initiated by Christian missionaries in China that sought to introduce Chinese architectural features into their plans for Christian schools and colleges in China. These include Shandong Christian University in Jinan, St John’s University in Shanghai, Ginling College for women in Nanjing, and University of Nanking campus, also in Nanjing.

A precedent had been established and thereafter it became the norm for schools and universities, and later, other kinds of civic buildings – town halls, museums, municipal offices – to proclaim their Chinese-ness by incorporating traditional Chinese architectural features in their overall design, though often this meant no more than placing a token Chinese-style roof on what was otherwise an entirely Western construction.

When it came to the turn of young Chinese architects working in China just after the end of World War I, many of whom had at one time or another been employed by Henry Killam Murphy (1877–1954), the leading American exponent of college campus architecture in a contemporary Chinese style, it was only natural that they should follow suit. But there was a marked difference in their thinking.

What had originally been conceived as a way of persuading the Chinese to abandon their traditional beliefs for the Christian faith was now turned on its head and seen as an expression of Chinese nationalism and self-regard – the physical embodiment of Chinese aspirations in the modern world. A famous instance of this and one that has a Singapore connection is Xiamen University (previously known as Amoy University), founded in 1921, which was largely financed by a massive endowment from Singaporean industrialist Tan Kah Kee.4

The Chinese Renaissance, as an architectural movement, was relatively short-lived in mainland China – around 50 years in all – beginning with the early experiments of the Christian missionaries at the turn of the 19th century to the defeat of the Nationalist Government in 1949 and the proclamation of the People’s Republic of China. After that, the style fell out of favour on the mainland. It continued, however, to be popular in Taiwan where there are a number of notable Chinese Renaissance buildings from the 1950s and beyond. Examples include Nanhai Academy campus (1950–60s); Grand Hotel (1953–73); National Place Museum (1965); and National Theatre and Concert Hall (1987) – all of which are found in Taipei and its vicinity.

Singapore’s Chinese Renaissance

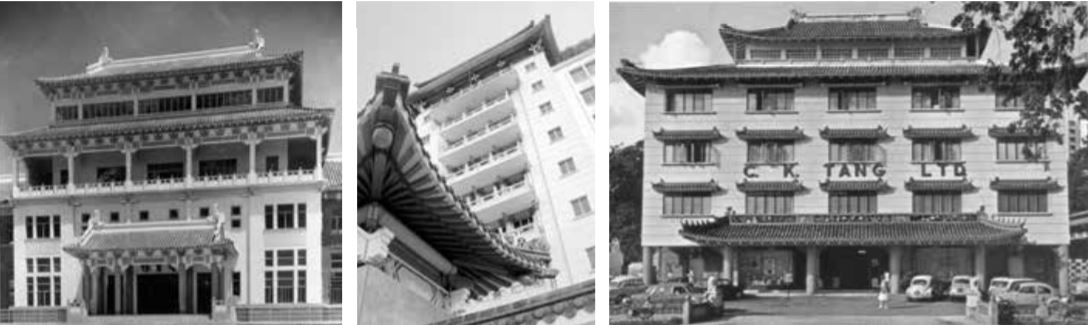

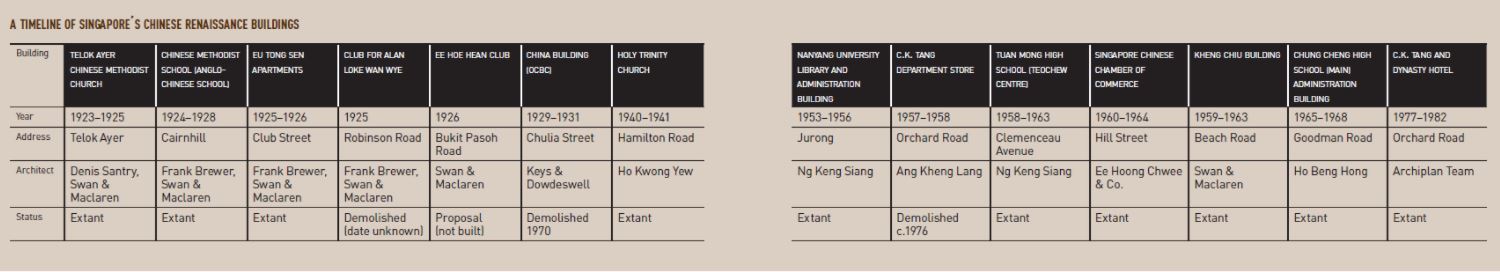

Singapore too has its share of buildings in the Chinese Renaissance style, mostly dating from the post-war era. These include Nanyang University Library and Administration Building (1953–56); the old C.K. Tang department store on Orchard Road (1957–58, demolished 1982); Tuan Mong High School on Clemenceau Avenue (Teochew Centre today) (1958–63); Kheng Chiu Building on Beach Road that houses the Hainanese clan association and Tin Hou Kong temple (1959–63); Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce on Hill Street (1960–64); and Chung Cheng High School (Main) Administration Building (1965–68).

The parallels with pre-war China and post-war Taiwan are self-evident. Although these buildings – an exception being Chung Cheng High School – belong, somewhat paradoxically, to the years immediately before independence, they are all about nation-building and the quest for a new architectural identity in the post-colonial era – a style that was at once modern but also reflected local (i.e. non-Western) sensibilities and history. Apart from Kheng Chiu Building on Beach Road, which was designed by the British architectural practice, Swan & Maclaren, the other buildings are the work of Singaporean architects – Ng Keng Siang, Ang Kheng Lang and Ee Hoong Chwee – all of whom, one assumes, shared similar goals and aspirations with their confrères in China and Taiwan.

Before the World War II, however, the circumstances surrounding the erection of first-generation Chinese Renaissance buildings in Singapore were rather different, though even here one finds parallels with China, since it was Christian missionaries who introduced the Chinese Renaissance style of architecture to Singapore.

Telok Ayer Chinese Methodist Church

The earliest example of Chinese Renaissance architecture in Singapore is the Telok Ayer Chinese Methodist Church in Telok Ayer, commissioned by the American Methodist Mission and erected between 1923 and 1925. Its architects were Messrs Swan & Maclaren, the leading architectural practice of the day, with Denis Santry the man responsible for drawing up the plans. His brief was to design an “institutional church” in the heart of Chinatown that would serve the needs of Chinatown’s burgeoning Christian community – the term “institutional church” in Methodist parlance meaning a place where worship, education and recreational activities all come together under one roof.

Up until this time, most church buildings erected in Singapore were in the Gothic Revival style, which was the architecture of choice for ecclesiastical buildings in late 19th-century Britain.5 The Telok Ayer Chinese Methodist Church completely broke with that tradition, and from the very outset it was clear that this was not going to be an ordinary church with a nave, transept and pews, but rather a wholly modern structure designed specifically to meet the requirements of the client.

In terms of its construction, it was a modern four-storey, concrete-frame building with a flat roof; stylistically it was part-Byzantine and part-Chinese in execution. Most radical of all, though, was the allocation of space. To begin with, the main congregational hall where church services were held was not on the ground floor as one might have expected, but on the floor above – a large auditorium with a seating capacity of 800, as well as vestries for the minister and choir. This allowed the ground floor to be used for recreational activities: games, classes, nativity plays at Christmas – in short, various amusements intended to encourage people to come to church. The third floor provided living quarters for two pastors and their families, while the top floor consisted of a roof terrace with a Chinese-style pavilion at one end that provided fine views of Telok Ayer and its environs.

Not long after work had begun on site, The Straits Times reported in February 1924 that this was “an entirely new plan in Church architecture as far as this part of the world is concerned and its ingenious and effective lay-out and novel and attractive design reflect much skill on the part of the architects, Messrs Swan and Maclaren”.6

Completed in early 1925, the Telok Ayer Chinese Methodist Church was consecrated by Bishop Titus Lowe on 25 April the same year. In his address, Bishop Lowe noted that the “building was a new departure in the line of making a church a great and useful social centre, the idea here being to “create a social atmosphere which would make it possible for both young and old alike to enjoy the fellowship of each other”.7 He drew attention to the fact that the building was “distinctly Chinese”, adding that “for this matter they [the Church] were indebted to the architects… in attempting to give them a building that was characteristic of Chinese art”.

In reality, Santry’s design was no more like a traditional Chinese building than it was a conventional church, the upturned eaves of the rooftop pavilion notwithstanding. If anything, it is more Byzantine Revival, the arcaded loggias and arrangement of the side windows within recessed alcoves contributing to this impression. All the same, it was the building’s Chinese elements that seem to have caught the untrained public eye. The Straits Times described the new church as being “distinctly Chinese in appearance, its most characteristic feature being a quaint gabled tower surmounting the roof, and finishing off the design of the frontage very effectively”.8

Chinese Methodist School (Anglo-Chinese School)

Telok Ayer Methodist Church was closely followed by another Swan & Maclaren commission from the American Methodist Mission, this time for a new school building at the summit of Cairnhill. The existing Methodist School – the forerunner of today’s Anglo-Chinese School – was located at Coleman Street at the time, next door to the American Methodist Chapel where the school had moved to soon after it was founded in 1886.9

By the beginning of the 1920s, the Coleman Street buildings were no longer able to accommodate the ever-increasing student population – the school was already obliged to schedule two sessions a day to cope with the existing enrolment of 1,500 pupils – and so the Mission started looking for a suitable location to expand the school. A plot of land on the summit of one of Cairnhill’s twin peaks was purchased in 1923 for $65,000, following which the title deed was transferred to the government in return for a lease with a duration of 999 years. With the site secured, the school authorities invited Swan & Maclaren to design a building on it.

Described in the newspapers as “semi-Chinese”,10 the new Anglo-Chinese School building was completed in 1924 to a design by British architect Frank Brewer, another leading figure at Swan & Maclaren in the 1920s. Located off Oldham Lane – named after pioneer Methodist missionary William F. Oldham who was also the school’s founder – the first sight that greeted visitors to the school was its imposing three-storey entrance pavilion, which skilfully combined Chinese and Art Deco detail. At the back of the entrance pavilion were two floors of classrooms arranged around an internal courtyard, or atrium.

One of the most striking features of the building was the broad canopy roof over the ground floor windows, a feature that was also repeated on the floor above in the three-storey block that fronted the site. Supported by massive brackets, the eaves of the canopy roof were swept up at the corners in the typical Chinese manner, as did the eaves of the main roof. As well as making an impressive visual statement, these tiered roofs worked together to cast long shadows over the external walls of the building during the middle of the day when the sun was at its highest point, shielding the classrooms within from the warming effects of solar radiation.

The internal courtyard also acted as a cooling mechanism, allowing warm air inside the classrooms to escape via the open atrium, and replaced by cooler air drawn in from the outside through the many door and window openings, thus creating a constant circulation of air through the building (it worked like a gigantic chimney flue). This system of natural ventilation was further enhanced by the school’s breezy hilltop location, which simultaneously made the most of ambient air currents.

Eu Tong Sen’s Apartment Blocks

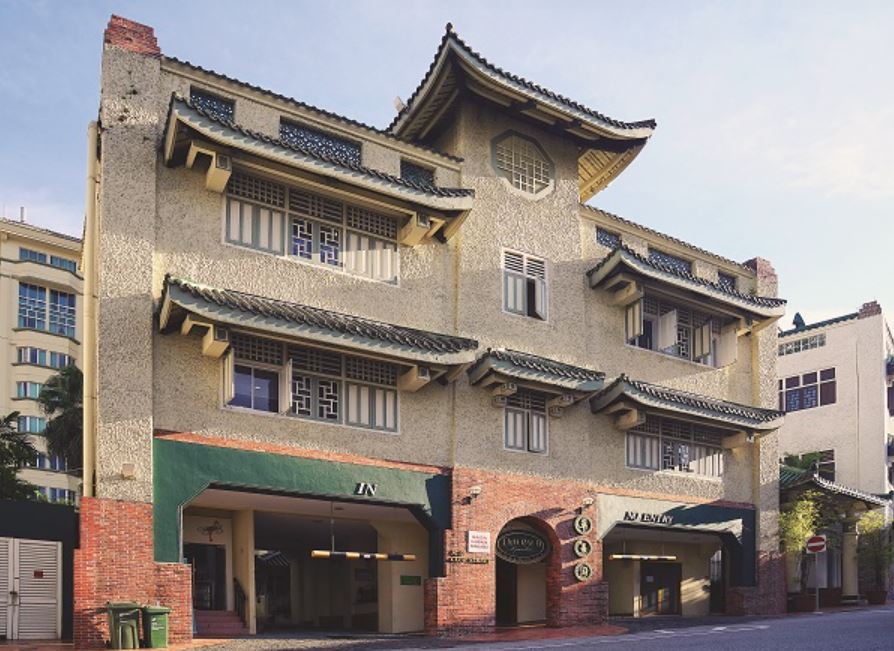

Frank Brewer revisited the Chinese Renaissance in 1925 when he designed two blocks of flats on Club Street for Eu Tong Sen, a prominent businessman and leader of the Chinese community. This was at a time when apartment living was just beginning to take root in Singapore.

But whereas previously, this new type of accommodation had been intended for a mainly European clientele, in this instance the prospective occupants were clearly meant to be Asian; in 1925, no European would have dreamed of putting up in Chinatown, thanks to its shady reputation as a hotbed for secret societies, brothels, gambling dens and opium shops. Possibly, it was this consideration that encouraged Brewer to opt for a Chinese Renaissance-style building, which at once signalled its modernity and yet retained a characteristically Chinese flavour.

Generally speaking, many supposedly Chinese-style buildings from this period, both in Singapore and elsewhere, are little more than a pastiche – even bordering on the kitsch – since the Western architects who designed them had little real understanding of traditional Chinese architecture and were probably not too bothered to find out. Brewer’s two apartment blocks for Eu Tong Sen, however, were different and went some way beyond the typical “Western-style building with a Chinaman’s hat on top” approach, revealing that Brewer had at least taken the time to acquaint himself with some of the basic precepts of Chinese architectural practices and building typologies.

The basement floor of the main building (which is on the left as one heads up Club Street from the Cross Street junction), for example, with its central, unadorned arch and fair-faced brickwork, brings to mind Chinese gateways from the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). Similarly, the slightly tapering profile of the tower is reminiscent of the classic silhouette of a Chinese drum tower.

Other “traditional” Chinese features include the canopy roofs over the windows, which rest on Chinese-style brackets protruding from the wall; one sees a similar arrangement in the canopy roofs of shophouses. The tiles were imported from China (unlike the v-shaped tiles normally used for shophouse roofs, which were manufactured locally), and came adorned with decorative, green-glazed “stoppers”, or endpieces (wadang), for the roof margins; the origins of the latter can be traced back to the second millennium BCE.

The upturned corners, which are every Westerner’s idea of what a Chinese roof should look like, are perhaps the least successful aspect of the edifices – and smacking of Chinese tokenism – but the composition of the window mullions and transoms is convincing, as they are derived from traditional Chinese latticework patterns, albeit greatly simplified here.

Chinese Art Deco

There are several other Chinese-inflected buildings dating from the 1920s, notably Eu Court (1925), Great Southern Hotel (1927) and Theatre of Heavenly Shows, today’s Majestic Theatre (1928). All three were commissioned by Eu Tong Sen and designed by Swan & Maclaren, but they are more Art Deco in character, albeit with Chinese flourishes – a kind of Shanghai chic that was all the rage back then.

There was, however, one other major building from this period that managed to be both Art Deco and Chinese Renaissance at the same time. This was the headquarters of the newly created Oversea-Chinese Banking Corporation (OCBC) on Chulia Street,11 which was designed by the British partnership of Keys & Dowdeswell in 1929.

Best remembered for the Fullerton Building (today’s Fullerton Hotel), home to Singapore’s General Post Office, which had been completed the previous year, Keys & Dowdeswell were riding the crest of a wave, having temporarily displaced Swan & Maclaren as the architects of choice for large-scale corporate commissions in the latter half of the 1920s. Other major works by Keys & Dowdeswell at this time include the Mercantile Bank of India building in Raffles Place and the Kwantung Provincial Bank on Cecil Street, as well as a six-storey office block on the corner of Finlayson Green and Robinson Road for the Dutch shipping line, Koninklijke Paketvaart - Maatschappij, or KPM for short.

The China Building, as the OCBC building was known, was Keys & Dowdeswell’s only venture into the realm of Chinese Renaissance architecture – a massive, five-storey Art Deco block capped with a Chinese pavilion wrought in reinforced concrete – but it made a huge impact.

Much of the building’s Art Deco-style ornamentation was modelled after the firm’s Fullerton Building – similar detailing was used for its Capitol Theatre and the adjoining four-storey apartment-cum-shop complex known as Namazie Mansions at the corner of Stamford and North Bridge roads in 1930, giving rise to the term “GPO architecture” – but the attic storey was full-blown Chinese Renaissance with its imitation roof brackets (dougong) supporting upturned eaves surmounted with stylised “dragon” ornaments (chiwen) at the four corners.

The OCBC building was the last major Chinese Renaissance-style building to be erected by British architects in pre-war Singapore. At this early stage, it was almost exclusively British architects who embraced the Chinese Renaissance style. Local architects were not much inclined to take up the cause until after World War II. Why was this so?

Many local architects who qualified to practise under the Architects Ordinance of 1926 were schooled in Western engineering and may have instinctively been attracted to more contemporary or “Modernistic” styles of architecture – mainly Streamlined Moderne – which exploited the potential of the latest building technologies, most notably reinforced concrete, rather than the retrospective traditionalism of the Chinese Renaissance movement.

One exception, however, was Ho Kwong Yew’s Holy Trinity Church at Hamilton Road. Ordinarily, Ho was very much the Modernist, but in 1940 he was commissioned to design a new church for the Anglican Foochow congregation, which sported Chinese-style roofs and fenestration with a stringcourse inscribed with the Chinese cloud or thunder pattern (leiwen). The Straits Times described it as “the first church in Malaya built in the Chinese style of architecture”,12 but of course they had overlooked Denis Santry’s church for the Methodist Mission at Telok Ayer. Completed in July 1941, Holy Trinity Church was the last building in the Chinese Renaissance style erected before the Japanese Occupation.

After World War II, it was a different scene altogether with Singaporean Chinese architects coming to the fore, embracing the Chinese Renaissance style with gusto in response to the outpouring of nationalist fervour, although Swan & Maclaren did make one more important contribution: the Kheng Chiu Building on Beach Road.

Somewhat ironically, though, by the time nationhood was achieved in 1965, the world had moved on and Chinese Renaissance, as an architectural style, was beginning to sound like old news. The last major Chinese-style building of any consequence to be constructed in Singapore was the C. K. Tang and Dynasty Hotel complex (1977–1982), but that can hardly be thought of as Chinese Renaissance in the sense of the term as has been described here. What was seen as a rebirth was, in fact, a dead end.

In 1926, the famous Ee Hoe Hean Club, otherwise known as the “Millionaires’ Club” – home to wealthy Chinese businessmen, financiers, shipping magnates, tin towkays, rubber barons and their like – commissioned Swan & Maclaren to design new premises for them at Bukit Pasoh.

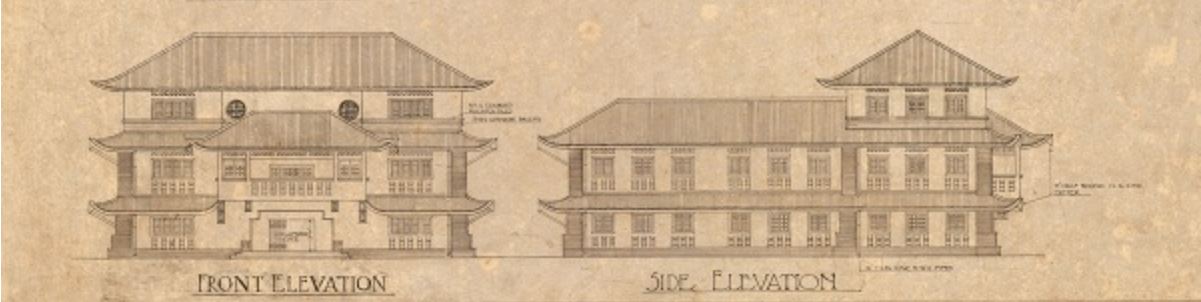

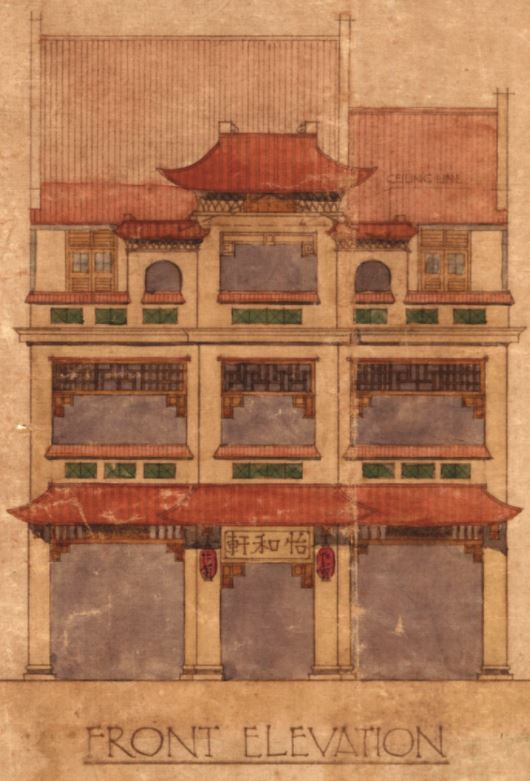

The architectural plan showing the front elevation of the Ee Hoe Hean Club to be erected on Bukit Pasoh Road, 1927. The original plans were for a Chinese Renaissance-style building but in the end, club members opted for a more contemporary look, which is the building we see today. Building Control Division Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The architectural plan showing the front elevation of the Ee Hoe Hean Club to be erected on Bukit Pasoh Road, 1927. The original plans were for a Chinese Renaissance-style building but in the end, club members opted for a more contemporary look, which is the building we see today. Building Control Division Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The original plans were for a Chinese Renaissance-style building, and one cannot help but draw the conclusion that members of the building committee were influenced by Eu Tong Sen’s apartments at the foot of Club Street – the original Ee Hoe Hean Club (established 1895) was at 28 Club Street at the time, a stone’s throw from the apartments. Although Swan & Maclaren’s original building plans were beautifully executed, in the end club members decided to go for a more contemporary look, which is the building we see today on Bukit Pasoh Road. The club is still around today; the membership remains exclusively male and by invitation only.

Dr Julian Davison is currently writing a history of Singapore’s oldest architectural practice, Swan & Maclaren, whose origins go back to the late 1880s. He is anthropologist, architectural historian and former Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow. The book is scheduled to be published in the last quarter of 2017.

Dr Julian Davison is currently writing a history of Singapore’s oldest architectural practice, Swan & Maclaren, whose origins go back to the late 1880s. He is anthropologist, architectural historian and former Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow. The book is scheduled to be published in the last quarter of 2017.

NOTES

-

Doon, D. (1936). Architectural chronicle. T’ien Hsia Monthly, 3 (4), 358–362. The article was republished in the online China Heritage Quarterly, June 2010, China Heritage Project, Australian National University. ↩

-

Cody, J.W. (1996, December). Striking a harmonious chord: Foreign missionaries and Chinese-style buildings, 1911–1949. Architronic, 5 (3), 1–30. Retrieved from iBrarian website. ↩

-

Cody, Dec 1996, p. 5. ↩

-

When it came to Tan’s buildings in Singapore, however, it seems that he preferred to adopt a Western style of architecture: Edwardian Baroque for the Chinese High School at Bukit Timah (today’s Hwa Chong Institution), which was founded by Tan in 1919 (the school building dates from 1923); Beaux Arts for his residence at Cairnhill (1926); and Art Deco for his rubber goods factory in Kallang (1930). ↩

-

Two notable exceptions are the Armenian Church, consecrated 1835, and the Cathedral of the Good Shepherd, consecrated in 1847, which are both neo-Classical in conception, but then they date from before the Gothic Revival style became popular in Britain. ↩

-

The new Chinese church. (1924, February 2). Malayan Saturday Post, p. 24. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Opening of Telok Ayer Chinese Church. (1925, April 27). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

A Chinese church. (1925, April 27). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

It was a boys-only school in those days as girls attended their own school, known as Methodist Girls’ School today, on Selegie Road. ↩

-

Anglo-Chinese School. (1928, November 19). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Oversea-Chinese Banking Corporation was formed from a merger of Ho Hong Bank, Chinese Commercial Bank and Oversea-Chinese Bank in 1932. ↩

-

New church in Horne Road. (1941, July 14). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩