Secret War Experiments in Singapore

The story of the Imperial Japanese Army farming bubonic plague-bearing fleas as biological weapons is very much fact, not fiction. Cheong Suk-Wai delves deeper.

A few days before Christmas in 2017, North Korea threatened to load its intercontinental ballistic missiles with anthrax-carrying microbes and fire them into the United States. (Anthrax is a highly fatal infection caused by the bacterium Bacillus anthracis.)

Anthrax-tipped missiles might seem like the fantasy of a delirious despot – until one learns that anthrax and the bubonic plague were developed right here in Singapore by the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) for use as biological weapons during World War II. Like North Korea, the IJA threatened to kill hordes of people by dropping disease-carrying bombs on them. But unlike North Korea (for now), the IJA actually carried out the nefarious deed during World War II.

The plague, which is spread by rats, is highly infectious and has a death rate of between 50 and 100 percent. It is sometimes called the Black Death because its victims’ lymph nodes swell into dark boils and the skin turns black from gangrene. The worst plague outbreak to date occurred in Europe between 1347 and 1350, when almost 65 per cent of the continent’s population was wiped out, making it one of history’s most devastating pandemics.

The IJA sought to re-enact the Black Death in Asia – its main target being the obliteration of enemies in mainland China – through its top-secret biological warfare research operative known as Unit 731. The unit was set up sometime between 1932 and 1935, with its headquarters in Shinjuku, the Tokyo ward with the world’s busiest train station today. From this Shinjuku unit later sprang a second Asian command centre in Harbin, in northeastern China. The Harbin unit answered to its parent unit in Shinjuku.

Besides Shinjuku and Harbin, Unit 731 was also found in Singapore. The Singapore branch, known as OKA 9420 (“oka” meaning “hill” or “height” in Japanese), was set up just days after the Fall of Singapore on 15 February 1942. Like the unit’s other branches, OKA 9420 was run by some of Japan’s top doctors and scientists. Its first head was Yoshio Hareyama, who was soon replaced by Ryoichi Naito.

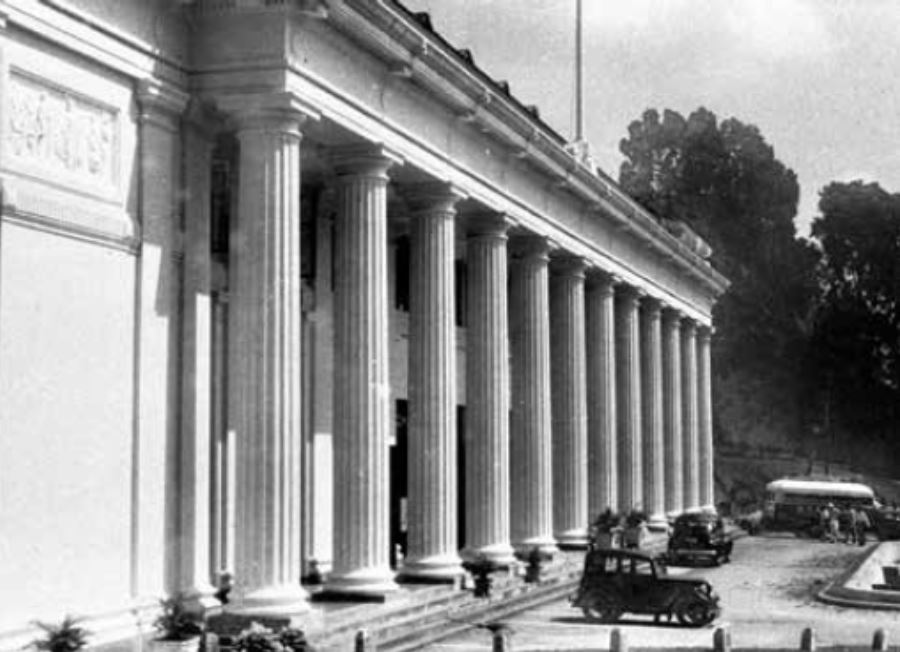

The latter and his colleagues worked out of the stately building at Outram Park – the Singapore General Hospital’s College of Medicine today (and home to the Ministry of Health). As Singaporean war survivor Geoffrey Tan, 91, recalled in his 2001 memoir Escape from Battambang: A Personal World War II Experience, the building housed up to six labs for Unit 731’s diabolical remit. These were designated as Dai-ichi (No. 1), Dai-ni (No. 2), Dai-san (No. 3) and so on. Tan worked in Dai-ni.

Burrowing Through Bookshelves

In September 1991, the Straits Times wrote about the activities of Unit 731 following an interview with a former Singapore cabinet minister.1 The Straits Times subsequently published a number of articles on this topic.2 Over two decades later, this issue resurfaced after Singaporean researcher and collector Lim Shao Bin was invited by the Singapore Society of Asian Studies to speak on the subject at the National Library on 4 November 2017. The Straits Times followed up with a newspaper report on 13 November. 3 Lim, 61, began ferreting out the ugly truths about Unit 731 when he was in his 20s, poring through piles of books and papers cramming the dusty shelves of bookshops lining shabby but genteel Kanda Street in Tokyo.

Lim is no eccentric, but an avid history buff and collector of memorabilia such as old postcards and photos of Singapore. His quest to uncover and piece together hidden details of the Japanese Occupation, including the atrocities of Unit 731, is his way of finding closure for his paternal grandfather’s senseless murder by the Japanese just after they surrendered to the Allied Forces in 1945 (see text box below).

It helped that the younger Lim is equally adept at reading, writing and speaking Japanese. His study of the language is so serious that he has taught himself old Japanese script, the language in which the books and documents he sought were written. Over some 40 years, Lim rifled through and acquired all the wartime records and other documents he could find on Unit 731.

Lim did not, however, rely on Kanda Street alone. His burning questions about Unit 731 spurred him to trawl the internet for clues of its heinous activities. Lim may be an amateur researcher or, as he puts it, “an investigator of war crimes”, but his zeal and eye for detail are impressive. For instance, he was able to refer me to an August 2002 paper by the late American scholar Sheldon H. Harris, and point to references in it to OKA 9420, including the 150 physicians who worked at the Singapore unit.

He adds that Unit 731 not only had a lot of clout, but also an “extraordinary” budget for its activities. Lim said he gleaned this from the 1991 memoir by a former OKA 9420 worker, Koichi Takebana, entitled Fleas, Rats and Plague: I Saw All Three. Crucially, Takebana’s book contains vital information about OKA 9420’s chain of sub-units. This was instrumental in helping Lim retrace the murky workings of this clandestine unit because the chain showed Singapore to be the Southeast Asian headquarters of Unit 731, along with other units in the Malayan towns of Tampoi in Johor and Kuala Pilah in Negeri Sembilan.

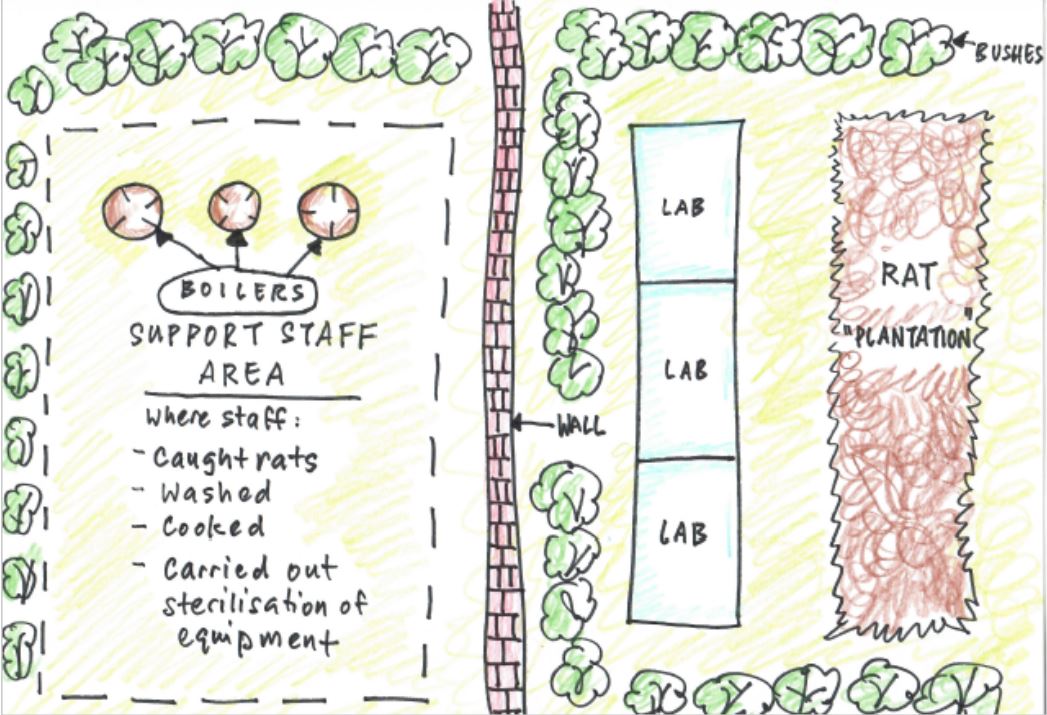

In his memoir, Takebana also said that when he was first shipped in to Singapore, he reported for work at OKA 9420 at Outram Park. He started out as a clerk of sorts but later took charge of the huge boilers in the unit’s backyard, and soon became aware of what he called the “critical” (i.e. biological warfare development) lab within the area, which had huge facilities.

The Workings of OKA 9420

Ironically, it was claimed that OKA 9420 was set up to rid Singapore of the plague and other infectious diseases. Some among its 600-strong staff thought that was true. Among them was Geoffrey Tan, who was one of those involved in making the anti-tetanus vaccine in Dai-ni lab. Tan stuck it out for four months before quitting. When Lim met Tan recently and asked him why he was willing to work there in the first place, the latter said that if the Japanese were developing vaccines against tetanus, “they cannot only be doing bad things”.

In 2000, former Singaporean cabinet minister Othman Wok, who worked as a lab assistant in OKA 9420, wrote in his biography, Never in My Wildest Dreams, that he was certain Singapore had been a base for making biological weapons.4 For one thing, he was made to trap rats and then check his rodent bounty for fleas, which his colleagues in the lab would then retrieve for later use. Unfortunately, Othman, who died on 17 April 2017 at the age of 92, did not say more in his book about OKA 9420’s shady misdeeds.

But Lim unearthed more on this subject in Kanda Street. Besides the plague, he learnt from wartime documents found in Kanda Street bookshops that OKA 9420’s three labs cultivated such pandemic horrors as cholera, smallpox, malaria, typhus, dysentery and anthrax.

In some British wartime documents, there is also mention of the malaria parasite cultivated in the Singapore labs and used to kill hundreds of British soldiers in 1942 when the IJA invaded Buin and Bougainville Island in Papua New Guinea.

No Need for Bullets

Harbin, the capital city of Heilongjiang province in China, is today famous for its beer and the annual ice sculpture festival, but during World War II, its outlying hamlet Pingfang served as Unit 731’s hub in China.

Lim’s research shows that after Japan unleashed the Nanjing Massacre between December 1937 and January 1938, Unit 731 began researching the optimal conditions necessary for breeding biological weapons, such as plague-carrying fleas from rats, in order to obliterate the Chinese economically and efficiently.

Tropical Singapore and Malaya were ideal breeding grounds because Unit 731’s research showed that fleas thrived best in places that had temperatures of between 27 and 30 degrees Celsius, and 90 percent humidity.

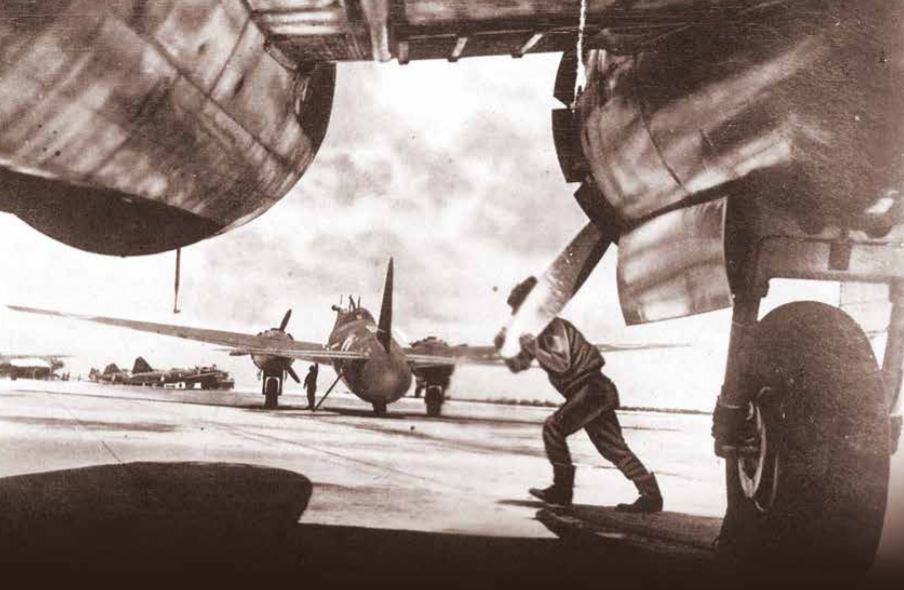

Despite these hospitable conditions, it appeared that there were insufficient rats in Malaya and Singapore for IJA’s diabolical ambitions. Hence, in late 1943, the Japanese military transported 30,000 rats by military jets from Tokyo to Singapore to bolster the local rat population. The IJA also sent truckloads of the vermin to two places in Malaya: Permai Hospital in Tampoi, in the middle of a Johor jungle, and a school in Kuala Pilah. The Japanese also sent rats to Bandung in Indonesia.

The rats flown in from Japan, along with those caught locally, were housed in what Lim calls “plantations” within the OKA 9420 compound in Outram Park. Each rat farm, as it were, consisted of a hut within a small garden. The floor of each hut was a huge metal plate, bolted down. On each plate rested four cages, into which the rats were released. It must have seemed like heaven as food scraps were scattered liberally about these cages.

Once the captive rats were bloated from the frenzied feeding, the lab workers would inject them with the plague bacteria. When the rats became sick, millions of fleas would be unleashed on them. The bloodsuckers went straight to work, feeding on their dying prey.

Lab workers would then isolate the fleas, now swollen with plague-rich blood. This involved an ingenious plan of shovelling flea-embedded soil or sawdust into a box, with mounds of dirt atop the box, and then shining a light on the fleas at an angle. The fleas, which hated the glow, would then flee to the box’s darkest corners, where lab workers would scoop them up as one would raisins. The “raisins” would then be examined under microscopes in the labs, which were located right next to the plantations. Here, lab workers had to “verify” if the fleas were incubating the plague bacteria in their systems, according to Lim.

Millions of the “verified” fleas were then flown to Thailand every two or three months “in big glass jars”, says Lim, ready for Japanese war planes to drop on their hapless foes.

Wartime records show that 10,000 rats sickened by the bubonic plague could yield 10 kg of plague-bearing fleas – and one needed only 5 g of fleas, or an estimated 1,700 fleas, to finish off around 600 people, as Lim learnt from reading the documents. With 10 g of fleas, the effects were quadrupled, easily wiping out as many as 2,400 people at once. “The Japanese found it a most effective weapon of war”, he notes. On one of their subsequent bombing blitzes, war planes carrying clay bombs filled with oxygen and plague-infected fleas obliterated more than 9,000 people in China, according to Chinese wartime records. “There was no need for bullets”, adds Lim wryly.

From a 2009 Japanese research report, Lim further learnt that in June 1940, 3,031 people in China’s Jilin province died after being infected by plague-bearing fleas originating from Unit 731, while in October that same year, another 9,060 people died in Zhejiang province, located south of Shanghai.

To top it off, and as an experiment, Japanese land troops contaminated the wells of several of the villages they invaded in Zhejiang with bacteria. “That was so senseless”, observes Lim, noting that they never repeated that experiment.

OKA 9420 maintained huge boilers that bubbled and belched steam 24 hours a day so that workers always had boiling water on hand to disinfect themselves and sterilise their equipment instantly. Meanwhile, Lim learnt from online Japanese wartime records that the Japanese disposed of the rat carcasses by incinerating them in nearby furnaces built for that express purpose.

In late June 1945, OKA 9420 suddenly vanished from Singapore – weeks ahead of the official Japanese surrender on 12 September 1945. At first, everyone at its Tampoi base moved wholesale to Singapore on 15 June that year, and then nine days later, the entire arm was relocated to Laos for no discernible reason. Its workers also burned all traces of their records and research in Singapore, says Lim grimly, leaving no evidence of its existence.

Free but not Forgotten

Lim says that OKA 9420’s head Ryoichi Naito and his colleagues were never tried as war criminals. “After the war, the Americans occupied Japan”, he recalls. “They started interviewing and tried to arrest war criminals. And one critical thing they sought more information about was biochemical warfare in Harbin. They wanted the key men.”

The Americans tracked down Naito who, in his fluent English, told them that he would turn over all the medical records, data from experiments and papers to the US on condition that they let him walk free. The Americans did just that, granting Naito and the rest of Unit 731 immunity from prosecution for war crimes.

Naito, his deputy Iichiro Otaguro and their ilk went on to rebuild their lives by, among other things, setting up clinics to treat everyday folk, joining academia and rising to professorships and, in some instances, becoming politicians.

But the truth eventually surfaced. “In the 1980s and 90s”, says Lim, “the doctors among these men started to retire and mentor younger doctors. When the latter found out that their mentors had done such bad things, they were shocked”.

Some of these younger doctors formed non-governmental organisations, which published accounts of what their founders had learnt about Unit 731’s experiments. Why was Japan not rocked by such findings? Lim puts it down to the thick fog of negation surrounding Japan’s war crimes, including from Japan’s powerful and vociferous right-wing politicians. Also, he mused sadly: “Children do not appreciate their grandfathers’ histories.”

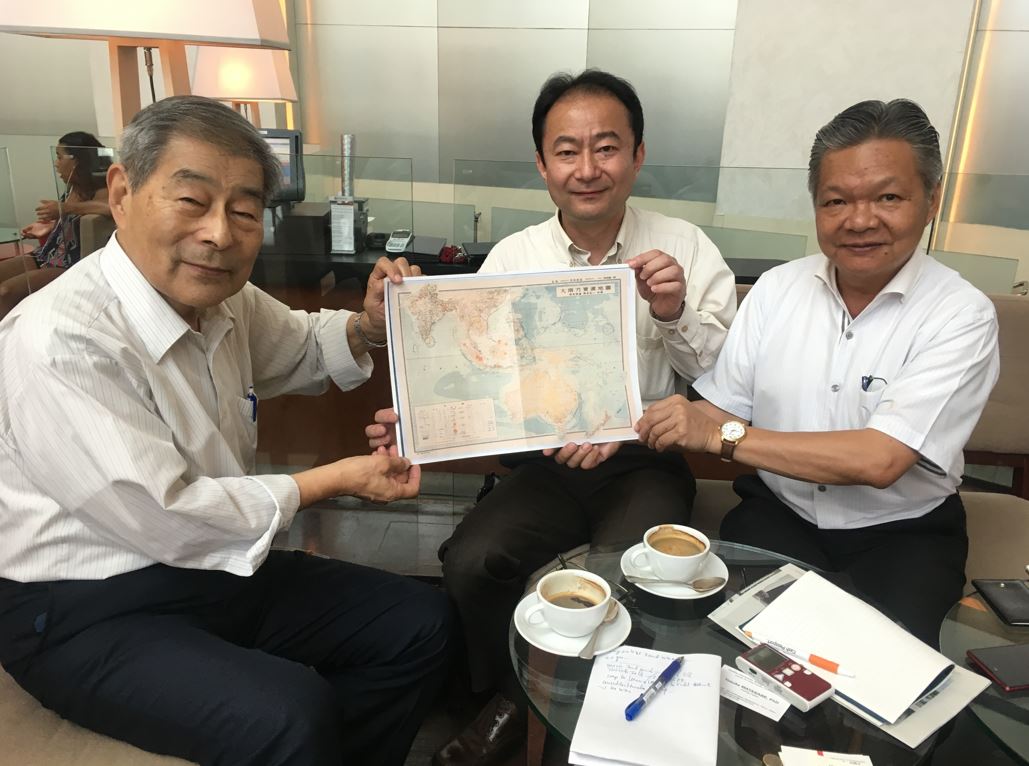

Some Japanese do, though. On 15 February this year, Lim introduced me to Nobuyoshi Takashima, 76, professor emeritus at Ryukyu University, who has been researching the dark days of the Japanese Occupation in Singapore and Malaya for more than 40 years. As Prof Takashima speaks no English, his friend, Dr Yosuke Watanabe, 47, visiting fellow at the Center for Asia-Pacific Partnership, Osaka University of Economics and Law, acted as translator.

When I asked Prof Takashima what, as a Japanese, he would like to say to Singaporeans, he hesitated and then said: “Now is the time for making peace from humanism, not for condemning war criminals.” He hoped that the OKA 9420 stories that Lim has unearthed would spur Singaporeans to learn more about their history.

Prof Takashima added that his interest in Unit 731 was piqued when one of his students took him to visit the Tampoi site in the 1980s. That started him off on his quest to uncover the atrocities committed by the IJA in Southeast Asia. “The Japanese Occupation is not researched much in Japan”, he told me, explaining why, in 1983, he established his now-yearly Takashima Tours, taking a busload of his countrymen on tours of former World War II sites in Singapore and Malaysia. In the course of his travels, Prof Takashima came to know Lim, and the firm friends now meet and regularly exchange information on Unit 731 and the IJA via email.

In 2010, Prof Takashima wrote and published a guidebook of such sites in Malaysia, and in 2016, he published one such book on Singapore. Among his inner circle of enthusiasts are his 75-year-old wife Michi Takashima, Dr Watanabe and the journalist Fuyuko Nishisato, whose 2017 book on Unit 731 titled Behind Bayonets and Barbed Wire: The Secrets of Japanese Army Unit 731, has been mentioned by news agencies such as China’s Xinhua.

Prof Takashima and his contemporaries have also taken to visiting Singapore every February to commemorate the Fall of Singapore, followed by a chicken rice dinner with Lim at Chin Chin Eating House, a well-known coffee shop on Purvis Street.

What Lim cannot stomach, even more than the grisly fates of plague victims, is what he sees as Unit 731’s “lack of remorse” for any of their actions. He says of Unit 731’s surviving Japanese officers: “All these soldiers write about somebody else’s stories, not their own dirty work.”

In the 1970s, it was rare for a Singaporean to snag a scholarship to study and work in Japan, and most would be overjoyed at such an opportunity.

But when Lim Shao Bin won the chance to work for Japanese precision engineering company NMB – which was among the first Japanese multinationals to set up shop in Singapore after independence in 1965 – he had mixed feelings about it.

For one thing, he had rued since he was a boy that his paternal grandfather, Lim Kui Yi, had died at the hands of Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) soldiers during the Japanese Occupation.

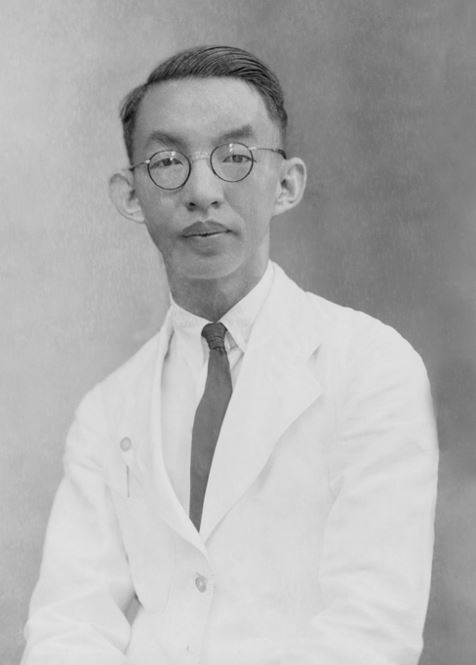

A portrait of Lim Kui Yi, the paternal grandfather of Lim Shao Bin whom the Japanese Imperial Army killed in Melaka on 5 September 1945. Courtesy of Lim Shao Bin.

A portrait of Lim Kui Yi, the paternal grandfather of Lim Shao Bin whom the Japanese Imperial Army killed in Melaka on 5 September 1945. Courtesy of Lim Shao Bin.

Lim, who was born in 1957, remembers, “When I was a kid, I was just told ‘Grandpa had been killed during World War II’.” So I assumed he was killed by Japanese aerial bomb attacks in Singapore.

“But after I got the scholarship, my father told me the truth: Grandpa had been killed after the Japanese surrendered in August 1945.” His grandfather was the head of the feedback unit of Melaka’s temporary city council, set up right after the Japanese surrender to give the city some semblance of governance. On 5 September, the council members celebrated Japan’s defeat at Jonker Street by waving flags of the Kuomintang, the Chinese party led by General Chiang Kai-shek that defended China against the marauding IJA during World War II.

According to Lim’s father, Lim Chow Sin, the open revelry enraged the Kempeitai, the Japanese secret police who were still around in Melaka at the time. “So on 5 September 1945, they stabbed Grandpa to death and threw his body down a well in Pulau Besar, Melaka”.

Thus, when Lim Shao Bin touched down in Japan for the first time in 1980, at the age of 23, he felt conflicted. “It was quite confusing; I was supposed to learn from these people but I also thought, ‘I shouldn’t learn blindly from this place’.”

But as a true Singaporean who was “a bit kiasu”, he did his best at work. Yet, burning within him was one big question: “Why was there a war in Malaya to begin with?” So began his quest to understanding all he could about the Japanese Occupation – and also, as he says, find “closure” for his grandfather’s senseless killing.

Every month, he would have to report to NMB’s Tokyo office on Kanda Street, where the bookshops were. He recalls: “After visiting the office, I would drop by the bookshops and soon found that I could find wartime documents if I was patient enough.”

The budding collector started small, rifling through the bookshelves for old postcards. He started to find things relating to Singapore. Paying tribute to Kanda’s old-style shops and their owners, he says: “It’s a special trade. When they purchase something to put on their shelves, they price their purchases with pride and professionalism. So if they say something is worth 2,000 yen, you can be assured they are right. They respect sincere collectors.” Kanda’s bookshop owners also, up till recently, traded on “cash only” terms.

Lim adds: “World War II split Japan into two worlds. Before the Japanese surrendered, they were so confident of themselves. They learnt from the West but modernised their culture, including language, without the need of foreign languages like English.” This occasionally led to some blind spots; for instance, there is no traditional Japanese word for “rubber” because the trees had never grown in Japan.

But, Lim notes, when Japan lost the war, Japanese egos were deflated, and of one of the repercussions was that people began corrupting the Japanese language with words from the English lexicon, resulting in a Japlish form called waise-eigo, yielding mish-mash words such as bakku-mira (“back mirror”), chia-garu (“cheergirl” or cheerleader) and hafu (a “half-blood” or person of mixed ancestry).

Today, he considers himself a bona fide, if not formally trained, “historian” and sometimes refers to himself as a “historical detective” – and one keen to revive interest in Singapore’s history before the nation gained independence on 9 August 1965. He says wistfully: “After independence, I think we emphasised too much on what was happening on this small island and lost the history of the years before 1965.”

Since 2012, he says, visitors to quiet Kanda Street have trebled. It is more proof that history does matter, for the increase in literary foragers is due to China and Japan’s squabble over the necklace of islands south of Japan, which China claims under the name Diaoyu, and which Japan knows as Senkaku. The tensions are still taut today; on 31 January 2018, China ordered the Japanese consumer goods giant Muji to destroy all its catalogues that contained what China called “a problem map” because it omitted the Diaoyu/ Senkaku islands. Lim says: “There are now buyers from the US, Japan, China, Taiwan and Korea in Kanda, all looking for books on Diaoyu or Senkaku.”

Lim’s most recent sojourn to Japan was in early December 2017 to join his friend, Nobuyoshi Takashima, at the World Peace Forum in the old port city of Yokohama. It is clear that Lim is as much a bridge-builder as he is a truth-seeker. Prof Takashima, 76, is professor emeritus at Ryukyu University, and he has been researching the war crimes of the IJA in Southeast Asia for the past 40 years.

The next step of Lim’s quest is to find someone who can help him read and decipher a cache of medical reports from Unit 731 written by Iichiro Otaguro. “After independence, so much of Singapore history emphasised the years after 1965. I would like what I’ve found to spur future generations of Singaporeans to rediscover the history of our war years. Let’s not make it a case of children forgetting their grandparents’ past”, says Lim with a pensive smile.

Cheong Suk-Wai is a lawyer by training and a writer by choice. A former ASEAN Scholar and Thomson Foundation Scholar, she has been a construction litigator, a journalist and a public servant.

Cheong Suk-Wai is a lawyer by training and a writer by choice. A former ASEAN Scholar and Thomson Foundation Scholar, she has been a construction litigator, a journalist and a public servant.Note: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that the details of Unit 731’s activities first came to light in 2017. Details of this unit were actually published in the Straits Times in 1991.

NOTES

-

Phan Ming Yen (1991, September 19). WWII germ lab secret. The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

See, for example, Phan Ming Yen (1991, September 25). US Army records mention wartime germ lab in S’pore.The Straits Times, p. 25; Phan Ming Yen (1991, November 11). Germ lab’s head says work solely for research, vaccinesThe Straits Times, p. 20. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Zaccheus, M. (2017, November 13). WWII S’pore used as base to spread disease. The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Othman Wok. (2000). Never in my wildest dreams. Singapore: Raffles. (Call no.: RSING 324.259570092 OTH) ↩